Abstract

Introduction: As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact workforces in the United States, the Acupuncture and Telehealth Survey was released to assess the acupuncture profession's use of telehealth and workforce response to a changing regulatory landscape.

Methods: An online cross-sectional survey of licensed acupuncturists in the United States was conducted in May 2020 for 4 weeks. Novel online recruitment strategies were successfully implemented including social media pages, digital media marketing, and webinar presentations. Statistical analyses were used to ascertain varying impacts on acupuncturists with telehealth training, and the use of online health care platforms, stratified by age, and history of licensure.

Results: One thousand forty-five respondents from 46 states completed the survey. The majority of respondents noted a significant reduction in working hours regardless of telehealth training history (mean −18.7 h/week, p < 0.001, 95% confidence interval [−19.5 to −18.0]); however, acupuncturists managing patients online reported a lesser magnitude of impact (mean −17.3, p = 0.004). Respondents noted stress, immune support, and pain as the most common conditions managed through telehealth. Acupuncturists using telehealth primarily educated patients on nutrition- or herbal-based therapies and acupressure techniques, similar to acupuncturists managing suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cases. Although only 21% of acupuncturists reported receiving telehealth training, 38% were providing telehealth, and 13% were considering it in the future with concerns for quality patient care.

Discussion: Acupuncturists' working hours were significantly reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic although many pivoted to a variety of online health care techniques and profession-specific modalities for continued patient care. This effect could be minimized by the use of telehealth platforms, necessitating adequate training on telehealth in the acupuncture profession.

Keywords: acupuncture, COVID-19, telehealth, survey, cross-sectional, telemedicine

Introduction

Regulatory changes since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, including but not limited to the allowance of virtual visits and limiting elective procedures,1 have indiscriminately affected the health care professions and their respective medical practices. This has occurred through sudden loss of insurance coverage by many Americans,2 a substantial decrease in patient volume,3 reduced clinical research capacity,3 and challenges in standard insurance coverage across states for virtual care visits.2 Health care providers rushed to comply with requirements for personal protective equipment, adjust to telehealth provision, and address the financial implications of the pandemic. It is likely that a greater proportion of private clinics and allied health care fields,4 especially those that more frequently utilize hands-on techniques (e.g., acupuncture, physical therapy, and massage), have been impacted disproportionately by these new regulations worldwide.5

Where possible, health care providers have pivoted to using virtual methods to interact with and treat their patients.6 The American Academy of Family Physicians broadly defines telehealth as “electronic and telehealth communications technologies and services used to provide care and services at-a-distance.”7 Insurance companies have implemented individual reimbursement and fee schedules for telehealth visits, which vary widely according to individual scope of practice and state of residence.8 Therefore, ensuring proper implementation of telehealth methods became a significant concern of health care regulatory agencies.9,10 A path to addressing this concern includes modernization of medical curricula, ensuring flexibility, and rapid adaptation to systematic changes in health care.11,12

From the perspective of adapting clinical practice to a virtual care setting, as well as training in methods and best practices for telehealth,13 acupuncturists may mirror other complementary and integrative health care professions that use hands-on techniques (e.g., massage therapists and chiropractors).14 East Asian medicine encompasses a broad variety of diagnostic treatment methods, including acupuncture, pulse and tongue diagnosis, herbal therapy, qigong, Tai Chi, and manually applied therapies such as acupressure, Gua Sha, and cupping, with practitioners most commonly, and throughout this article, recognized as “acupuncturists.”15 Virtual medical provision is a challenging concept for acupuncturists who practice these modalities. Some components of the patient/provider interaction can be conducted virtually; however, what remains unclear is the extent to which acupuncturists can adapt while effectively applying therapies, and the extent to which they have received training to do so.13

The goal of the Acupuncture and Telehealth (AcuTe) survey was to examine the impact of the COVID-19 regulatory changes on licensed acupuncturists in the United States, including the following: (1) changes in work hours; (2) current state of telehealth practices and previous telehealth training; (3) COVID-related online patients; and (4) use of digital media to maintain contact with patients.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This online cross-sectional study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington and developed according to STROBE statement guidelines.16 The study team utilized a community-engaged approach through informal interviews with licensed acupuncturists practicing in the United States and observed the acupuncture community on social media platforms. Second, previously published professional surveys for health care professions, including allopathic medical doctors and nurses, were reviewed. No professional acupuncture survey on the use of telehealth among licensed acupuncturists was available at the time of the survey design. Therefore, a literature review was conducted on the use and ethics of telehealth for medical doctors, which the study team utilized as guides for survey development and implementation. Each member of the research team (except C.B.-L.) was a licensed acupuncturist. Two members were also practicing clinicians who provided subject matter expertise in the development of the survey.

Participants were assessed for eligibility, provided written consent if determined eligible, and responded to the survey prompts within the online survey platform (Fig. 1). The eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) being an acupuncturist licensed to actively practice in the United States; (2) being able to read, speak, and understand English; and (3) having access to an electronic device. Those with inactive and emeritus acupuncture licenses were excluded from participation. Allopathic physicians who practice acupuncture under their medical license were excluded. However, allopathic physicians who were also licensed acupuncturists were eligible to participate. Individuals self-selected to enroll in the study and agreed to an online consent form. All responses were deidentified and confidential.

FIG. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram: diagram of screening, informed consent, and completed survey respondents. The CONSORT flow diagram depicts the process of 1,272 individuals who accessed the survey platform and potential steps in which they were determined to be ineligible or did not complete the survey. AcuTe, Acupuncture and Telehealth.

Recruitment

Participation was solicited through digital media including e-mails, social media, and webinars. A digital PDF flyer with a link to the survey was e-mailed to state and national acupuncture organizations, accredited acupuncture schools, institutional alumni organizations, and acupuncture product supply companies. A copy of the digital flyer text was embedded in the e-mail to facilitate ease of sharing with colleagues. A short synopsis of this study was shared in the monthly American Society of Acupuncturists' (ASA) and American Association of Naturopathic Physicians' (AANP) newsletters. The principal investigator presented at three acupuncture schools in Oregon, California, and Texas, and at an online Town Hall meeting organized by the ASA and National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (NCCAOM) to broaden the marketing reach of the study.

A website was created as a landing page with information about the study and the research team with a link to the survey. To further support the recruitment process, a social media page called Influential Point was created on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. The study team developed educational content catered to potential participants to further expand outreach. These posts included information regarding telehealth insurance codes, navigating social media, and clinical pearls.

Survey advertisements were posted on Facebook and Instagram every third day of the week. To improve engagement, new followers were sent a direct message to welcome them to the page with a link to the survey, and an invitation to participate. Instagram “influencers,” defined as any licensed acupuncturist in the world with more than 5,000 followers, were invited to share the survey in their Instagram and/or Facebook Story and/or feed.

The survey was open for 4 weeks from May to June 2020 with no financial incentives.

Survey variables and measurement

The survey was developed and disseminated using REDCap™, an open-source data collection web tool.18 Participants were provided with information about the purpose of the study, questions to determine their eligibility, approximate time to complete the survey, and the informed consent form. The 11-page survey included questions regarding demographics, the impact of COVID-19 on respondents' clinical practice, health care provision for suspected and/or confirmed COVID-19 patients, telehealth services, history of telehealth training, and attitudes toward integrating telehealth into practice. Participation was anonymous and voluntary.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were used to establish demographic data. For variables reported within a range, transformations to median values were performed. Proportions, contingency tables, chi-square calculations, as well as independent and paired t-tests were performed using RStudio (v.1.2.5033).19 Power was calculated post hoc against data published by Fischer et al.,20 suggesting a sample size of 418 required for 99% power at a 99% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Participant demographics

The survey was completed by 1,045 individuals. Precisely 1,272 prospective participants reached the study platform, with 227 incomplete or ineligible submissions; thus, 82% of potential participants who accessed the survey completed it. Participation was elicited from each U.S. state except Alabama, Arkansas, North Dakota, South Dakota, and West Virginia (Fig. 2). Respondents were predominantly female (81%, n = 841), white (76%, n = 790), and 35–44 years of age (34% n = 350) (Table 1). A notable right-skew was present before data transformation for age and use of telehealth by chi-square analysis. To reduce skewness, a single response set from the 18–24-age group was incorporated into the 25–34-age group post hoc. The most commonly reported additional licenses were massage, naturopathy, and nursing. Of the total respondents, 72% were individual proprietors (n = 748), 12% were salaried employees (n = 126), 10% were independent contractors (n = 106), and 6% had a mixture of employment types, had recently experienced unemployment, or were working in a commission-based setting (n = 65). The majority of respondents reported learning about the survey through a newsletter/e-mail, Facebook advertisements, or attending a webinar.

FIG. 2.

Number of complete responses by state. The map portrays the number of respondents who completed the survey according to their geographic location of practice in the United States. State abbreviations are used according to standard two-letter abbreviations.

Table 1.

General Characteristics of Licensed U.S. Acupuncturist Respondents

| n | % of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,045 | 100.0% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 841 | 80.5% |

| Male | 186 | 17.8% |

| Nonbinary/third gender | 10 | 1.0% |

| Prefer not to say | 8 | 0.8% |

| Age group | ||

| 18–24 | 1 | 0.1% |

| 25–34 | 151 | 14.4% |

| 35–44 | 350 | 33.5% |

| 45–54 | 295 | 28.2% |

| 55–64 | 164 | 15.7% |

| 65 or older | 84 | 8.0% |

| Race | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 | 0.2% |

| Asian or Asian American | 117 | 11.2% |

| Black or African American | 12 | 1.1% |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 9 | 0.9% |

| More than one race | 81 | 7.8% |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 6 | 0.6% |

| Unknown/not reported | 28 | 2.7% |

| White | 790 | 75.6% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 68 | 6.5% |

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 929 | 88.9% |

| Unknown/not reported | 48 | 4.6% |

| Employment type | ||

| Independent contractor | 106 | 10.1% |

| Individual proprietor | 748 | 71.6% |

| Other | 65 | 6.2% |

| Salaried employee | 126 | 12.1% |

| Years in practice | ||

| <10 years | 264 | 25.3% |

| <15 years | 198 | 18.9% |

| <20 years | 119 | 11.4% |

| <5 years | 279 | 26.7% |

| 20+ years | 185 | 17.7% |

| Additional license(s) | ||

| Massage | 62 | 5.9% |

| Naturopathic doctor | 52 | 5.0% |

| Nurse or nurse practitioner | 20 | 1.9% |

| Chiropractic | 12 | 1.1% |

| Nutrition/dieticians | 5 | 0.48% |

| Medical doctors | 5 | 0.48% |

| Other | 23 | 2.2% |

| Patient contact methods (participants can choose multiple) | ||

| None | 56 | 5.4% |

| 789 | 75.5% | |

| Newsletter | 268 | 25.6% |

| Social media | 464 | 44.4% |

| Phone call | 619 | 59.2% |

| Text | 582 | 55.7% |

| Blog | 125 | 12.0% |

| Online classes/events | 101 | 9.7% |

| Other | 42 | 4.0% |

| Multiple/all | 619 | 59.2% |

| Social media presence (participants can choose multiple) | ||

| 410 | 39.2% | |

| 301 | 28.8% | |

| 43 | 4.1% | |

| 41 | 3.9% | |

| TikTok | 3 | 0.3% |

| Other | 14 | 1.3% |

| Use of telehealth before COVID | ||

| No | 316 | 80.4% |

| Yes | 77 | 19.6% |

Impact on working hours

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, most acupuncturists reported working 21 h or more per week (76%, n = 789). A significant decrease in work hours was noted since the pandemic onset with the vast majority working 20 hours or less/week (80%, n = 838). Of all the employment types, individual proprietors reported the greatest magnitude of decrease in their working hours; however, all employment types reported a significant difference in work hours since the COVID-19 outbreak, at an average of −18.7 h/week (t = −49.5, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−19.5 to −18.0]). A subgroup analysis of respondents utilizing telehealth platforms reported a smaller degree of impact compared with those who did not (mean −17.3 and −19.6 h/week, respectively; t = −2.6, p = 0.04). The impact on working hours for respondents who had received prior training in telehealth noted no significant difference in the number of working hours lost compared with those who had not received training (t = 0.979, p = 0.164).

Telehealth training and practice

A small number of acupuncturists reported having received telehealth training in their professional life span (21%, n = 222, 95% CI [0.188–0.237]), of which the majority (71%, n = 157) reported the training was helpful. These respondents predominantly received their training online (91%, n = 202). When asked if they wish for additional training, 48% responded “definitely and probably yes.” The majority of respondents (67%) indicated a preference for online Continuing Education Units (CEU) for telehealth training, with a smaller number preferring school-based training (11%), in-person CEU (12%), or other (1%). For respondents who did not have a history of telehealth training before the time of the survey, 39% indicated “definitely and probably yes” that they wish for telehealth training, 30% “might or might not,” and 31% “definitely and probably not.” Overall, the respondents reported quality of care, patients' lack of technology skills, reimbursement, and misdiagnosis as main concerns with the use of telehealth (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Concerns with the use of telehealth. This bar graph indicates concerns with the use of telehealth reported by survey respondents. Participants were able to indicate more than one concern.

At the time of this survey, 49% of respondents (n = 513) reported they were not offering telehealth services, 38% (n = 393) were offering telehealth services, and the rest (13%, n = 139) were considering it. There was a higher average satisfaction rate for the use of telehealth in respondents with a history of training compared with those with no training (χ2 = 9.6, df = 4, p = 0.045). Of respondents seeing patients online, 80% (n = 316) were not offering telehealth services before the COVID-19 outbreak. A chi-square test of independence showed that there was a significant association between age and the current or future consideration of telehealth use (χ2 = 25.9, df = 10, n = 1,045, p = 0.004) with the 55–64-age group utilizing telehealth at least 11% less frequently than other age groups. There was also a significant relationship between years in practice and use of telehealth (χ2 = 15.97, df = 8, n = 1,045, p = 0.043). Those in practice less than 20 years used telehealth at a rate of at least 5% greater than those in practice greater than 20 years.

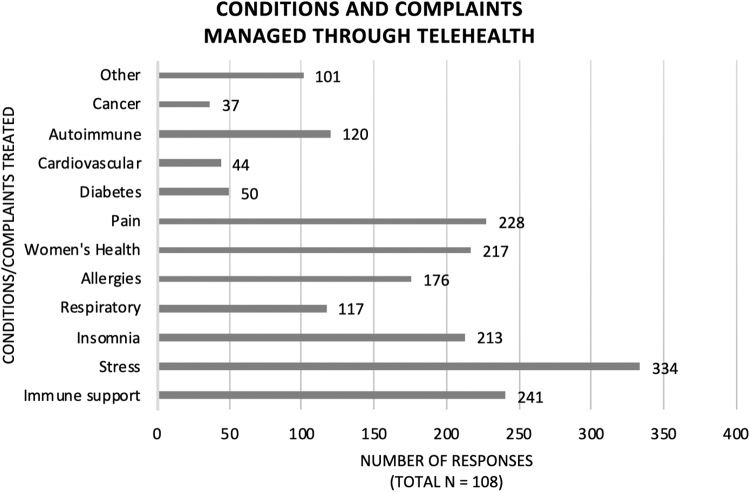

The most common services that were offered from respondents providing online health care (n = 393) were nutrition/food therapy (91%, n = 357), herbal therapy (90%, n = 352), and acupressure (68%, n = 266) (Table 2). Some acupuncturists also offered other non-East Asian medicine modalities such as meditation, coaching, yoga, and fitness. Respondents providing online visits (n = 393) reported these visits were primarily focused on managing stress (n = 334), followed by immune support (n = 241) and pain (n = 228) (Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Sample Distribution and Prevalence of Telehealth Use in the U.S. Acupuncture Profession

| n | % of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 393 | 100.0% |

| Use of telehealth before COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 77 | 19.3% |

| No | 316 | 80.4% |

| Total | 1,045 | 100.0% |

| Use of telehealth during COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 393 | 37.6% |

| No | 513 | 49.1% |

| Not yet | 139 | 13.3% |

| Total | 393 | 100.0% |

| Types of modalities offered via telehealth (participants can choose multiple responses) | ||

| Acupressure | 266 | 67.7% |

| Gua Sha | 95 | 24.2% |

| Herbal therapy | 352 | 89.6% |

| Moxibustion | 134 | 34.1% |

| Qigong/Tai Chi | 171 | 43.5% |

| Nutrition/food therapy | 357 | 90.8% |

| Self-massage | 229 | 58.3% |

| Other | 119 | 30.3% |

| Total | 393 | 100.0% |

| Reported conditions/complaints of online patients (participants can choose multiple responses) | ||

| Immune support | 241 | 61.3% |

| Stress | 334 | 85.0% |

| Insomnia | 213 | 54.2% |

| Respiratory | 117 | 29.8% |

| Allergies | 176 | 44.8% |

| Women's health | 217 | 55.2% |

| Pain | 228 | 58.0% |

| Diabetes | 50 | 12.7% |

| Cardiovascular | 44 | 11.2% |

| Autoimmune | 120 | 30.5% |

| Cancer | 37 | 9.4% |

| Other | 101 | 25.7% |

FIG. 4.

Conditions and complaints managed through telehealth. This bar graph indicates conditions and complaints respondents reported managing through telehealth. Participants were able to indicate more than one condition and complaint.

COVID-19-related online patients

A small percentage of respondents (10%, n = 108) reported seeing suspected and/or confirmed COVID-19 patients. Of these, the vast majority (87%, n = 94) were only seen online. Online services offered to patients with suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19 were similar to the broader respondent online services, most commonly herbal therapy (95%, n = 103), nutrition/food therapy (86%, n = 93), and acupressure (48%, n = 52) (Fig. 5). Additional online services offered were guided breathing techniques, botanical therapies, including essential oils and infusions, and self-applied physical techniques such as cupping and Gua Sha.

FIG. 5.

Type of modalities used with COVID-19-confirmed or COVID-19-suspected patients. The bar graph indicates online services survey respondents offered to COVID-19-confirmed or COVID-19-suspected patients. Participants were able to indicate the use of more than one modality.

Digital contact maintenance

Respondents reported that they maintained contact with patients primarily by e-mail, followed by phone call, text message, and social media. Of those who used social media (44%, n = 464), Facebook and Instagram were the most popularly used platforms (88%, n = 410 and 65%, n = 301, respectively) while Twitter (9%, n = 43), LinkedIn (9%, n = 41), and TikTok (<1%, n = 3) were used less frequently. Other digital media platforms acupuncturists reported using included various electronic health record systems (e.g., ChARM) and virtual meeting platforms (e.g., Zoom).

Discussion

Conducting an online study during the uncertainty of a global pandemic had unique challenges. One limitation of the study was that organizations, schools, and individuals were transitioning into quarantine, and may not have been checking their e-mails as frequently. The study team received e-mails from some state organizations and schools responding to the recruitment material after the survey closed due to school closures or limited capacity staffing. This could have increased the study's power and generalizability of findings if these respondents were included. This is compounded by a lack of respondents from some states, possibly due to communication lapses or decreased marketing penetration to the regions. As a counterpoint, the authors note there are no practice acts in Alabama and South Dakota and these results may not accurately reflect the professional population of the states. Furthermore, the eligibility criteria may have limited the potential to participant pool as the study required access to an electronic device and ability to read and write in English. A potential challenge to the generalizability of these findings includes a predominately female and white respondent demographic.

A second limitation is that recruitment using digital media may have introduced selection bias by excluding licensed acupuncturists who do not use or are not active on social media or who do not check their e-mails as frequently. In addition, although this survey was open for 4 weeks, unexpected events may have affected the recruitment, such as state-specific, phased reopenings including nonessential and allied health care practices.

The daily educational content posted on social media may have influenced some acupuncturists to consider offering telehealth services. The authors posted two social media posts related to telehealth. One post was about offering online services for nurses on International Nurses' Day, which included information on telehealth codes for acupuncturists. The second post, on World Telecommunication Day, shared ideas for patient support such as Zoom cooking classes and “teatime” with patients using Instagram Live, and queried followers on their utilization of digital media as acupuncturists. Since individuals self-selected themselves to participate in the study, it is difficult to assess if the educational content the authors posted influenced their decision to complete the survey.

Minor technical difficulties with the REDCap online survey also occurred. Two participants reported error messages when they tried taking the survey. No error was discovered on the back end of the online survey and the participants were invited to retake the survey, resulting in successful participation without any issues. However, the authors do not know how many other participants may have received a similar error message and were unable to complete the survey.

A core strength of this study was the high completion rate (82%) compared with other acupuncture professional surveys that were unaffiliated with a regulatory agency.21–23 The multistrategic approach to digital recruitment allowed the survey to be disseminated easily and quickly. In designing the online survey, the authors recognized the potential for survey burden and fatigue. To address these challenges, the survey was designed to be visually appealing with large fonts and adequate negative spacing between each question. It was also easy to navigate, accessible on all electronic devices (i.e., desktop, laptop, tablets, and mobile phones), and took ∼3–5 minutes to complete.

It is noteworthy to mention that 80% of respondents were not offering telehealth services until the COVID-19 outbreak. These results suggest there may be marginal benefit in the use of telehealth to prevent a loss in working hours during a pandemic. However, it does not appear that simply receiving training in telehealth lends to this cushioning effect.

Respondents addressed patient concerns, most notably stress and pain management,24–26 which have a substantial impact on the safety and well-being of the public during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although acupuncture is the main modality among American acupuncturists, respondents reported offering other modalities such as Chinese herbal therapy, nutritional food therapy, and qigong/T'ai Chi to support their patients in a virtual setting. Furthermore, some acupuncturists implemented an educational component to their online services by teaching patients how to apply cupping, Gua Sha, and moxibustion. The authors also learned that older practitioners and those practicing for more years were less likely to use telehealth. Finally, those who received prior telehealth training indicated the training was helpful.

These findings suggest a multiapproach digital media recruitment strategy and utilizing an online survey may be a more effective method to conducting professional surveys for licensed acupuncturists. The results from the study may indicate the need for telehealth training that addresses concerns of utilizing telehealth to improve quality of care, assisting patients who lack technology skills, and reimbursement issues. Lastly, this study will contribute to the growing literature of the profession-level impact of COVID-19.

Conclusion

The goal of the AcuTe online survey was to examine changes in work hours, telehealth services, and patterns in patient care and support during uncertain times as regulatory changes impacted the acupuncture profession in the United States. These findings suggest that digital media recruitment is an excellent tool to gain study participants but it requires planning and flexible strategic methods.

The long-term impact of COVID-19 on the acupuncture profession remains unclear. However, technology will continue to be a large part of lives, and may play a role in cushioning the impact of a pandemic on working hours in a health care profession that utilizes a number of manually applied therapies. In addition to preparing for future potential pandemics, the acupuncture profession may want to consider implementing telehealth training in graduate medical programs for various reasons such as broadening patient access, improving clinical skills unique to remote care, enhancing the patient/practitioner relationship, and supporting isolated patients in remote areas or due to disease process.

Authors' Contributions

T.L.L. directed the conception, design, and implementation of the study. T.L.L., B.O.L., J.N., A.S.-B., and C.B.-L. worked on the construct of the survey, accessibility, and administration. T.L.L., J.N., and A.S.-B. designed the recruitment strategy and implementation. B.O.L. performed statistical analysis for all data. T.L.L. and B.O.L. developed, critically reviewed, and edited the initial drafts of the article. J.N. and A.S.-B. reviewed and edited the article. C.B.-L. guided and informed the study team at all time points and participated in the development of the initial drafts of the article. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the submission of the article and meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Author Disclosure Statement

T.L.L., B.O.L., J.N., and A.S.-B. disclose licensure and regulation within the acupuncture profession. The authors have no further disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

The authors thank the National Institute of Health for grant funding for T.L.L. (5-T90-AT008544-05) and B.O.L. (3-R01-AT010271-03S1) for the construction and administration of this survey. The authors have no further funding recognition.

References

- 1. COVID-19 Resource for State Leaders: Executive Orders. State Executive Orders. Lexington, KY: Council of State Governments, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blumenthal D, Fowler EJ, Abrams M, Collins SR. Covid-19—Implications for the health care system. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1483–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beshyah SA, Ibrahim WH, Hajjaji IM, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical practice, medical education, and research: An international survey. Tunis Med 2020;98:610–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coto J, Restrepo A, Cejas I, Prentiss S. The impact of COVID-19 on allied health professions. PLoS One 2020;15:e0241328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lystad RP, Brown BT, Swain MS, Engel RM. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on manual therapy service utilization within the Australian private healthcare setting. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8:558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koonin LM, Hoots B, Tsang CA, et al. Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January-March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1595–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Physicians AAoF. What's the difference between telemedicine and telehealth? American Association of Family Physicians. 2021. Online document at: https://www.aafp.org/news/media-center/kits/telemedicine-and-telehealth.html Accessed May 15, 2021.

- 8. Kwong MW. State Telehealth Laws & Reimbursement Policies. 2020. Online document at: https://www.cchpca.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/CCHP%2050%20STATE%20REPORT%20FALL%202020%20FINAL.pdf Accessed May 15, 2021.

- 9. Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet (CMS.gov). 2020. Published March 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet Accessed May 15, 2021.

- 10. COVID-19 State Policy Guidance on Telemedicine. American Medical Association, 2020. Online document at: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-04/covid-19-state-policy-guidance-on-telemedicine.pdf Accessed May 15, 2021.

- 11. Lucey CR, Johnston SC. The transformational effects of COVID-19 on medical education. JAMA 2020;324:1033–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frogner BK, Fraher EP, Spetz J, et al. Modernizing scope-of-practice regulations—Time to prioritize patients. N Engl J Med 2020;382:591–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hyder MA, Razzak J. Telemedicine in the United States: An introduction for students and residents. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e20839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Impact of COVID-19 on the Physical Therapy Profession. 2020:4–13. August 2020. https://www.apta.org/contentassets/15ad5dc898a14d02b8257ab1cdb67f46/impact-of-covid-19-on-physical-therapy-profession.pdf Accessed May 15, 2021.

- 15. WHO Global Report on Traditional Complementary Medicine. 2019.

- 16. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370:1453–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lin K, Tung C. The regulation of the practice of acupuncture by physicians in the United States. Med Acupunct 2017;29:121–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bowman MA, Maxwell RA. A beginner's guide to avoiding Protected Health Information (PHI) issues in clinical research—With how-to's in REDCap Data Management Software. J Biomed Inform 2018;85:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Version 3.6.0. Vienna, Austria: R Core Team, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fischer SH, Ray KN, Mehrotra A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of telehealth utilization in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2022302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Sherman KJ, et al. Characteristics of visits to licensed acupuncturists, chiropractors, massage therapists, and naturopathic physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract 2002;15:463–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuo T, Christensen R, Gelberg L, et al. Community-research collaboration between researchers and acupuncturists: Integrating a participatory research approach in a statewide survey of licensed acupuncturists in California. Ethn Dis 2006;16:S98–S106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ward-Cook K. The 2017 NCCAOM Job Analysis Survey: A Report for the Profession of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine. 2019. Online document at: https://www.nccaom.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/2017%20NCCAOM%20Job%20Analysis%20Study%20Full%20Report%20with%20Appendices.pdf Accessed May 15, 2021.

- 24. Zhou X, Snoswell CL, Harding LE, et al. The role of telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemed J E Health 2020;26:377–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020;14:779–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. El-Tallawy SN, Nalamasu R, Pergolizzi JV, Gharibo C. Pain management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pain Ther 2020;9:453–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]