Abstract

Background:

Multiple prior studies have identified a detrimental effect of pediatric HIV on cognitive function. Socioeconomic status (SES) is one of the strongest predictors of cognitive performance, and may affect the relationship between HIV and cognition.

Methods:

As part of the ongoing HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders in Zambia (HANDZ) study, a prospective cohort study, we recruited 208 participants with HIV and 208 HIV-exposed uninfected controls, all aged 8–17 years. A standardized questionnaire was administered to assess SES, and all participants had comprehensive neuropsychological testing. An NPZ8 score was derived as a summary measure of cognitive function. Logistic and linear regression were utilized to model the relationship between SES and cognitive function, and mediation analysis was used to identify specific pathways by which SES may affect cognition.

Results:

Children with HIV performed significantly worse on a composite measure of cognitive function (NPZ8 score −0.19 vs. 0.22, p <0.001) and were more likely to have cognitive impairment (33% vs. 19%, p=0.001). Higher SES was associated with reduced risk of cognitive impairment (OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.75–0.92, p<0.001) in both groups, with similar effects in children with HIV and HEU groups. SES was more strongly correlated with NPZ8 score in children with HIV than in uninfected controls (Pearson’s R 0.39 vs 0.28), but predicted NPZ8 in both groups. Mediation analysis suggested that the effect of SES on cognition was most strongly mediated through malnutrition.

Conclusion:

Cognitive function is strongly correlated with SES in children with HIV, suggesting a synergistic effect of HIV and poverty on cognitive function.

Keywords: Socioeconomic status, Cognitive Functioning, Human immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Children

1.0. Introduction

Multiple studies have demonstrated that children with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) are at increased risk for developmental delay and cognitive impairment despite treatment with antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Kapetanovic et al., 2014; Meyer, 2014; Cohen et al., 2015; Pem, 2015a; Boivin et al., 2018). Mortality among ART-treated children with HIV has fortunately become increasingly rare, and central nervous system opportunistic infections as well as HIV-associated progressive encephalopathy have decreased in prevalence in regions in which ART is widely available. However, more subtle forms of cognitive impairment have increased in prevalence in both children and adults with HIV. In adults with HIV, longer duration of HIV, history of opportunistic infections, lower CD4+ T cell count nadir, and ongoing viremia have all been described as risk factors for HIV-associated Neurocognitive Disorders (HAND) (Hardy et al., 2009; Bearden and Meyer, 2016; Carroll and Brew, 2017). However, there are relatively few studies that have evaluated risk factors for cognitive impairment in the paediatric population with HIV, with even less information on children with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. (Ellis, Langford and Masliah, 2007; Anderson et al., 2015).

In diverse studies across multiple regions, socioeconomic status (SES) has been described as one of the strongest predictors of cognitive performance in the general population in both adults and children (Bangirana et al., 2009; Cohen et al., 2015; Mwanza-Kabaghe et al., 2015; Kandawasvika, Gumbo and Kuona, 2016; Kabuba, Jr and Heaton, 2018). However, most prior studies of cognition in children with HIV have minimally evaluated effects of socioeconomic status. Differences in SES between HIV positive and HIV negative control groups may confound comparisons of cognitive function between groups, as in most settings children with HIV come from lower SES groups than uninfected children. However, SES may worsen cognition by affecting HIV-specific factors such as timing of treatment initiation and adherence (Coscia et al., 2001; Cohen et al., 2015; Hoare et al., 2016; Phillips et al., 2016; Buda et al 2021).

In this study, we sought to investigate the relationship between SES, HIV, and cognitive function as part of a prospective cohort study, the HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in Zambia (HANDZ) study. Zambia is a sub-Saharan nation with high rates of HIV infection, with an estimated 12.4% of the adult population living with HIV in 2016. Fifty-four percent of Zambian Adults and 60% of children live below the nationally-defined poverty line (CSO, 2016; Sladoje, 2017; Zambian Ministry of Health, 2017), often leading to challenges accessing food, transportation, and education that may disproportionately affect the HIV-infected population. The goals of the current study are to 1) Identify which elements of SES have the strongest relationship to cognitive impairment in children with and without HIV, 2) Identify the effect of SES on HIV-specific factors including adherence and timing of treatment initiation, and 3) Evaluate potential mediators in the relationship between SES and cognitive function.

Methods

Methods of the parent HANDZ study have previously been described (Adams et al., 2019; Buda et al 2020; Buda et al 2021; Schneider et al 2020). Briefly, we recruited children and adolescents ages 8–17 with HIV from the Paediatric Centre of Excellence (PCOE), the major HIV referral centre in Lusaka, Zambia. HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) controls were recruited from the community by a trained community health worker. Stratified sampling was used to ensure that controls were recruited from the same neighborhoods in which children with HIV resided. All participants were recruited from 2017 –2018, and were seen for follow up every 3 months, with most participants having completed 2 years of follow up at the time of the current analysis.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Children and adolescents with HIV were confirmed to be HIV positive by Western blot or DNA PCR, had been taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) for at least one year prior to enrolment, and had at least one living parent who was available to give consent and participate in the study. HEU controls were included in the study if they were aged 8–17; their HIV-uninfected status was confirmed by immunoassay; and their mother was HIV infected during or prior to pregnancy. Participants were excluded from taking part in the study if they had a known history of central nervous system infection with an organism other than HIV, or chronic or acute medical or psychiatric conditions other than HIV that could potentially impact their participation in the study.

Sample Size and Power:

A sample size of 200 participants per group was initially planned based on simulation studies for each aim, with the goal of ensuring model stability and avoiding overfitting for regression models. The least power would be available to evaluate dichotomous outcomes (e.g. cognitive impairment) within subgroups. Assuming that rates of cognitive impairment were at least 20% in the HIV+ population, this sample size would ensure >80% power to detect odds ratios of 1.5 or greater in the logistic regression analyses. Participants were overenrolled by 4% to account for possible dropout.

Data Collected

A complete list of all variables collected and methods of measurement is described in the HANDZ protocol paper (Adams et al 2019). Key variables are described below.

Socioeconomic Status (SES) and Demographics:

Socioeconomic Status (SES) and Demographic Information was evaluated using a measure adapted from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey-5 (MICS5, http://mics.unicef.org/tools). The MICS5 Household Survey was shortened and modified to eliminate questions not relevant to an urban population. The survey evaluated access to running water and electricity, toilet facilities, food security, parental education, and income. As precise income information was often not available, income was approximated and categorized as low/medium/high for this population. Wealth was approximated through ownership of consumer items including a radio, refrigerator, gas or electric stove, computer, and television. One point was given for each of these if the possession was owned by the household, to form a “possession index” taking values between 0 and 5.

Additional Key Variables Measured:

Physical health and illness were assessed using a self-rating and parental rating of general health, number of times hospitalized, and HIV-specific variables including WHO Stage, current and lowest recorded CD4 count and percentage, and viral load. Health and illness variables were combined into an illness index, using penalized regression to determine variable weighting. Nutritional status was assessed using history of stunting, wasting, malnutrition or severe malnutrition according to standard WHO definition (determined from chart review), and weight for height, weight for age, and mean upper arm circumference percentiles measured at each visit, and these variables were combined into a malnutrition index using penalized regression for weighting as detailed below. Negative life events (e.g. exposure to violence or abuse, illness or death of a family member) were assessed using the negative life event index, a questionnaire developed for use in children in Zambia (Adams et al 2019).

Neuropsychological Assessment:

Neuropsychological testing was done using a combination of standard techniques and computerized testing using the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery. Neuropsychological testing details have been previously described (Adams et al., 2019). The cognitive domains evaluated were working memory, attention, set shifting, inhibition, immediate recall, processing speed, motor speed, verbal fluency, and nonverbal reasoning. An age-adjusted z-score was calculated for each domain, and these were averaged to create an overall measure of cognition referred to as the NPZ8 score. A global deficit score (GDS) approach was used to define cognitive impairment. In this approach, each domain score is converted into a deficit score from 0 to 5 based on standard deviations below mean performance, and these domain-specific deficit scores are averaged to create the GDS (Blackstone et al., 2012). By convention, cognitive impairment was defined as a GDS of 0.5 or greater.

Statistical Analyses:

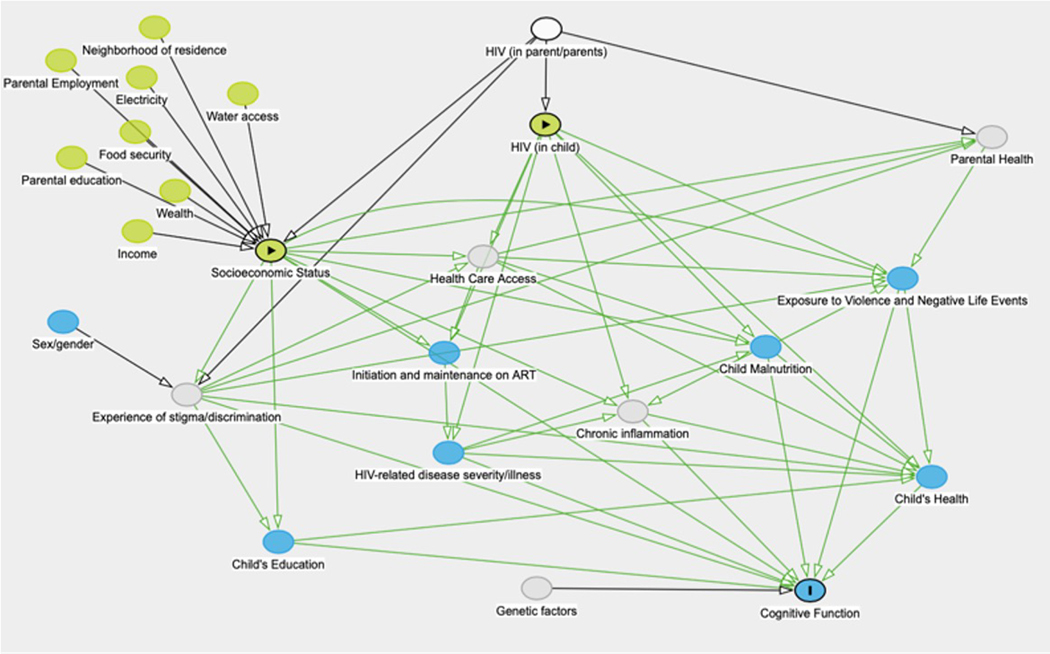

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 16.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Comparisons between variables were performed using t-tests for normally-distributed continuous variables, Kruskal-Wallis rank tests for ordinal or non-normally distributed continuous variables, and Chi-squared tests for dichotomous or categorical variables. Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between potential risk factors and cognitive impairment, and linear regression was used to evaluate the association between SES and NPZ8 score. Multivariable regression models were constructed using Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) for variable selection (see Figure 1). Adaptive regression splines using the “mvrs” package in Stata were utilized to investigate the linearity of the relationship between SES and NPZ8. Mediation analysis was performed using the “med4way” package in Stata 16 (Discaciatti et al 2019; Vanderweele 2014), with potential mediators selected based on the DAG. Each potential mediator was tested independently in a model including SESI as the exposure and NPZ8 score as the outcome. For each of the above described analyses, an initial model was fit including both HIV+ and HEU groups, and then separate models were fit for each group in order to include HIV-specific variables and to determine whether HIV status modified the effect of the variable. Missing data were treated with pairwise deletion.

Figure 1:

Directed Acylic Graph (DAG) demonstrating the potential causal path and mediators between socioeconomic status and cognitive function.

Dimensionality Reduction and Model Selection for SES Variables:

Due to the large number of SES variables collected, we used various techniques to combine SES variables into a socioeconomic status index (SESI) for dimensionality reduction. This is necessary in order to ensure the stability of regression models and prevent multicollinearity, due to the fact that SES variables are typically highly correlated and each individual variable may contribute only a small amount to the total variance. Using the SES variables described above, we constructed several different SES indices. In the first index (SESI1), we included all variables prespecified as of likely importance (maternal education, electricity, water, presence of a flush toilet, food security, income category, and possession index) and combined them using a simple points-based system, with continuous variables scaled to generate values between 0 and 2. We generated a second index (SESI2) using principal component analysis (PCA) of the variables listed above for comparison. We then used penalized regression including lasso regression and elastic net regression to identify a more parsimonious subset of SES variables that predicts cognitive function. For lasso and elastic net models, the total data set was split into two equal parts, a training set and a test set, and lasso (using cross-validated, plugin, and adaptive lasso models) and elastic net models were fit using all SES variables, and including HIV status, age, and sex in each model. Variable importance plots were constructed, and the “optimal” model was selected based on prediction (based on R-squared) of NPZ8 in the test set. The same methods were used to generate the illness indices and malnutrition indices described in the statistical analysis section detailed above.

Ethics Statement:

The institutional review boards of the University of Rochester (protocol #00068985), the University of Zambia (#004–08-17), and the National Health Research Association of Zambia approved this study. Verbal and written consent was obtained from the parents of all participants in the study. For participants who were older than 12 years, verbal and written assent was obtained as well.

Results

1.1. Demographics:

A total of 416 participants were enrolled in the study, including 208 with HIV and 208 HEU controls. However, only 389 participants (206 HIV+ and 183 HEU) completed all baseline assessments and had analysable data. All subjects with HIV were treated with ART, with the most common regimen being tenofovir, lamivudine, and efavirenz, a common first line regimen in this age group in Zambia. The majority were adherent to ART by both self-report and provider report, and most had undetectable viral loads at the time of enrolment. The mean duration of time on ART was 7.5 years. Most subjects with HIV had relatively high CD4 counts and were WHO Stage 1 at time of evaluation. Participants with HIV were more likely to have a variety of indicators of higher SES, including parental education, income, access to piped water, electricity, and food security (see Table 1). However, participants with HIV were more likely to have a history of malnutrition and severe malnutrition. Participants with HIV had significantly lower mean NPZ8 scores (−0.2 in HIV+ vs. 0.2 in HEU, p<0.001) and were significantly more likely to meet GDS criteria for cognitive impairment (33% vs. 19%, p=0.001) than HEU controls, indicating poorer cognitive function. Missing data were minimal (<2%) for most key variables, with the exception of information on paternal education and employment.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of population, stratified by HIV Status

| Variable | HEU N=183 n(%) | HIV+ N=206 n(%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 12.1 (2.9) | 11.7 (2.3) | 0.332 |

| Male Sex (% male) | 87 (48%) | 114 (55%) | 0.124 |

| Mother deceased (%) | 0 (0) | 18( 9%) | 0.001 |

| Father deceased (%) Missing data in n=140 |

23 (24%) | 37( 24%) | 0.968 |

| Attending school (%) | 157 (86%) | 190 (92%) | 0.04 |

| SES Variables | |||

| Years of Maternal education, mean (SD) | 6.2(3.5) | 7.5 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Years of Paternal Education, mean (SD) Missing in n=50 |

9.6 (2.6) | 10.3(2.6) | 0.005 |

| Monthly income in kwacha, mean (SD) | 1621 (1133) | 3086 (1970) | <0.001 |

| Possession Index, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (1–4) | <0.001 |

| Food insecurity (%) | 126 (69%) | 108 (53%) | 0.001 |

| Piped water as primary water source (%) | 47 (26%) | 97(47%) | <0.001 |

| Electricity in home (%) | 133 (74%) | 162 (80%) | 0.170 |

| History of malnutrition (%) | 8(4%) | 63(31%) | <0.001 |

| History of Severe malnutrition (%) | 5 (3%) | 43 (21%) | <0.001 |

All Values are Mean (SD), Median (IQR), or n (%)

1.2. Individual risk factors for cognitive impairment

Risk factors for impairment differed between HIV+ and HEU groups (see Table 2). In the bivariable logistic regression analysis in the HIV+ group, the strongest associations with cognitive impairment included self-reported poor health, SES indicators including possession index, water, food insecurity, and presence of a flush toilet in the home, the nutritional indicators stunting and low weight for height, and several measures of HIV disease severity including worst recorded WHO Stage, mean viral load, and lowest recorded CD4 count (see Table 2). In the HEU group, stunting and low weight for height had an even stronger relationship with cognitive impairment, but the SES indicators of food insecurity, water, and having a flush toilet were not significantly associated with impairment. Of note, not being in school was associated with cognitive impairment in participants with HIV but not in HEU participants; school type (e.g., private vs public) was not associated with cognitive performance in either group. Among participants not attending school, 85% listed financial reasons as the primary reason for not being able to attend school due to inability to afford school fees.

Table 2A.

Bivariable analysis of risk factors for cognitive impairment in participants with HIV

| Variable | Impaired N= 70 | Unimpaired N=136 | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 11.9 (2.2) | 12.4 (2.4) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.14 |

| Male sex (% male) | 34 (49%) | 80 (59%) | 0.66 (0.4–1.2) | 0.16 |

| Self-reported poor physical health (%) | 12 (17%) | 9 (7%) | 2.9 (1.2–7.4) | 0.02 |

| Not in school (%) | 9 (15%) | 5 (5%) | 3.2 (1.01–10.1) | 0.047 |

| SES Variables | ||||

| Low maternal education (<7 years) | 20 (30%) | 28(22%) | 1.5 (0.8–3.0) | 0.21 |

| Low paternal education (<9 years) | 19 (30%) | 22 (19%) | 1.8 (0.9–3.7) | 0.10 |

| Median Possession Index (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 3.5 (2–4) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.003 |

| Food insecurity (%) | 46 (66%) | 62 (46) | 2.2 (1.2 – 4.1) | 0.009 |

| Piped water in home (%) | 23 (33%) | 74(55) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 0.003 |

| Electricity in home (%) | 52(75) | 110(82) | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 0.26 |

| Flush toilet in home (%) | 17(24) | 62(46) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 0.003 |

| Nutritional Markers | ||||

| Growth Stunting (%) | 36(52%) | 30(22%) | 3.8 (2.1–7.1) | <0.001 |

| Low weight for height (%) | 38 (55%) | 36 (27%) | 3.4 (1.8–6.2) | <0.001 |

| History of malnutrition (%) | 23(33) | 40(29) | 1.17(0.6–2.2) | 0.61 |

| History of severe malnutrition (%) | 18(26) | 25(18) | 1.5 (0.7–3.1) | 0.22 |

| HIV Specific Variables | ||||

| History of WHO stage 4 (%) | 37(56%) | 53(41%) | 1.81(1.0–3.3) | 0.05 |

| Early initiation of ART (<1 year) | 6 (9%) | 16 (12%) | 0.7 (0.3–1.8) | 0.45 |

| Lowest recorded CD4 count<200 | 10 (16%) | 7 (6%) | 3.2 (1.1–8.7) | 0.01 |

| Mean viral load>4,000 copies/ml | 10 (17%) | 8 (7%) | 2.8 (1.0–7.5) | 0.04 |

| Median Illness Index | 4 (3–5) | 2.5 (2–4) | 1.7 (1.3 – 2.3) | <0.001 |

All variables are displayed as n (%), mean (SD) or median (IQR)

1.3. Results of Penalized Regression Models:

The models selected by Lasso and elastic net included 2–5 SES variables (see Supplementary Table 1), with the most parsimonious model including only maternal education (as a continuous variable) and possession index. Additional variables selected included whether the mother completed any post-secondary education (e.g. college or professional school), presence of piped water in the home, and whether the father completed any post-secondary education. Of all models evaluated, the Lasso Plugin had the best performance in the test set (R-squared of 0.12; other models R-squared in the test set all 0.09). In comparison, the original SESI variable (based on prespecified variables of presumed importance) had an R-squared of 0.17 in the test set. As our original SESI variable outperformed the data-driven indices, we proceeded to use the original SESI variable in all remaining analyses.

1.4. Relationship between SESI and Cognitive Outcomes

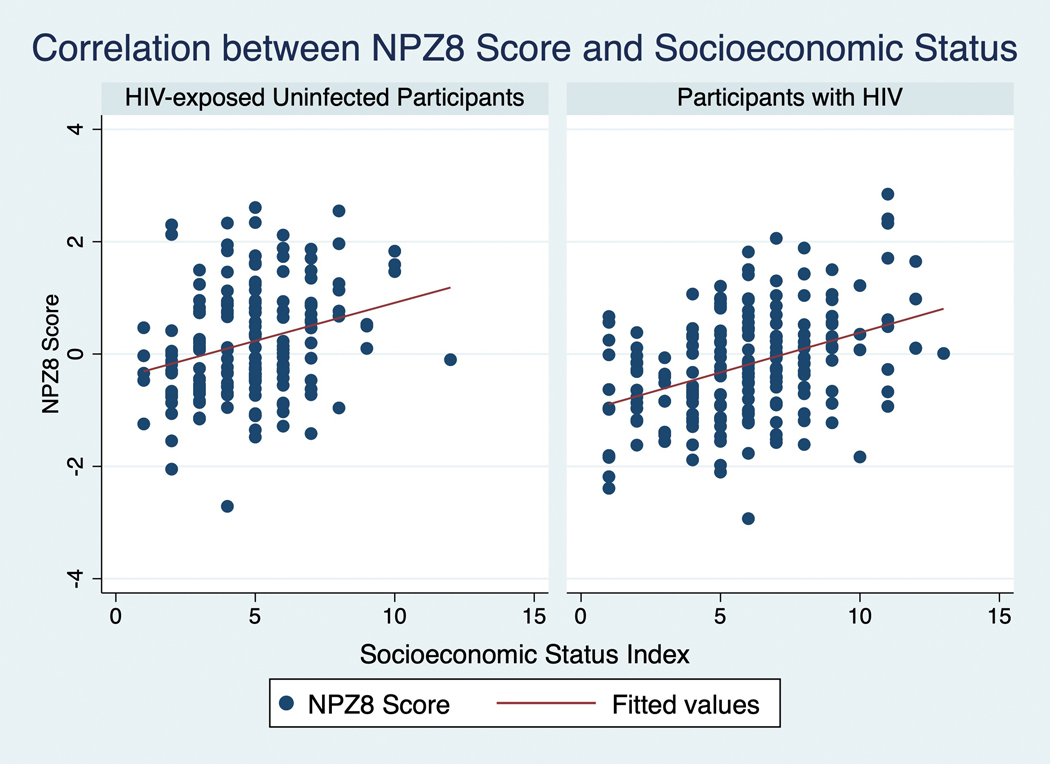

SESI was more strongly correlated with NPZ8 in participants with HIV than in HEU participants (Pearson’s R 0.39 vs 0.28; see Figure 2), but the association was highly significant in both groups (p<0.001). In a multivariable linear regression model controlling for age, sex, and HIV status, SESI remained strongly associated with NPZ8 (B=0.15, 95% CI .11–.19, p<0.0001). SESI alone accounted for 15% of the variance in NPZ8 in the HIV+ group, and 8% of the variance in the HEU group. Higher SES was associated with a reduced rate of cognitive impairment (OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.75–0.92, p<0.001; see Figure 3) in both groups, with similar effects in HIV+ and HEU groups (see supplementary Figure 1). Adaptive regression splines did not identify any “knots”, or threshold effects in the relationship between SESI and NPZ8, suggesting that SESI has an approximately linear relationship with NPZ8.

Figure 2:

Correlation Between NPZ8 Score and Socioeconomic Status Index (SESI), demonstrating a stronger relationship between SESI and NPZ8 in patients with HIV (Pearson’s R 0.39 in participants with HIV vs 0.28 in HEU participants).

2. Relationship Between SESI and HIV-specific variables

SESI was significantly associated with worst recorded WHO Stage, with higher SESI predicting worst WHO Stage of 1 (OR 1.2, 95% CI 1.2–1.5, p=0.01); that is, higher SES was associated with less severe disease stage. SESI was not statistically associated with early initiation of ART (at 12 months of age or younger; OR 2.9, 95% CI 0.9–9.3, p=0.08), having a lowest recorded CD4 count of less than 200 (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.7–1.1, p=0.16), or having an elevated viral load (>2000 copies/ml) in the prior two years (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.7–1.0, p=0.13), though these varibles all trended towards better disease control in participants with higher SES. There was no association between SESI and any measure of adherence.

3. Mediation Analysis

We analyzed four potential mediators in the relationship between SES and cognitive function: malnutrition (treated as a continuous variable using the malnutrition index), school attendance(treated as a dichotomous variable based on whether the participant was enrolled in school at the baseline visit), negative life events (treated as a continuous variable using the negative life events index), and physical health/illness (as indicated by the illness index). Mediation analysis suggested that the effect of socioeconomic status on NPZ8 was partially mediated through malnutrition, which mediated 15% of the total effect (see Supplementary Table 2). Ten percent of the total effect of SES on NPZ8 was mediated through illness/poor physical health, while 14% was mediated through not being in school, although confidence intervals were wide and crossed the null for both of these variables. Negative life events did not appear to mediate the effect of SES on cognition, and were not significantly associated with NPZ8 score. We did not find any evidence of interaction effects between variables.

Discussion

In this study we sought to investigate the relationship between socioeconomic status, HIV, and cognitive function in a prospective cohort study of Zambian children, and to identify which SES variables had the strongest relationship with cognitive function.

Socioeconomic status was found to have an approximately linear association with cognitive functioning in both children with HIV and HIV-exposed uninfected children. However, a stronger relationship between SES and cognitive performance was observed in children with HIV, and a number of SES variables were associated with cognitive impairment in children with HIV but not in HEU controls. Of note, in contrast to most studies of HIV in children, children with HIV in our study came from families with significantly higher SES than HEU children. This was primarily driven by a small number of middle class professionals (e.g. nurses, teachers) who were parents of children with HIV in the study, with this same group not well-represented in the control population. However, the absolute difference between groups was small, and there was substantial overlap between participants with and without HIV on most SES measures. There were two likely reasons for the fact that participants with HIV had higher SES in this cohort. First, participants with HIV with higher SES (and thus more funds available for transportation, or potentially greater medical knowledge) might choose to get their care at PCOE as it has a reputation for higher quality care and shorter wait times compared to community clinics. Our control population was recruited from the community, and thus, may represent a more typical SES group of patients followed in the public sector in the Lusaka area. The second reason is that due to the longitudinal nature of the study, middle class patients in the community might have chosen not to participate due to the time commitment involved, whereas for parents of children with HIV the additional time commitment was relatively minimal as the study visits were scheduled around clinic visits which would have occurred regardless of study participation. Despite the fact that the HIV+ group was wealthier and had better food security, it was notable that malnutrition, stunting, and wasting, were all more common in the participants with HIV. Chart review and review of growth curves suggested that in most cases this was due to wasting that occurred prior to starting ART, and thus likely due to increased metabolic demands and HIV-associated cachexia. In many cases, after starting ART, participants had an increase in weight and BMI, but remained growth stunted, suggesting that there may be a critical period in early childhood in which interventions could be targeted. Further details of these nutritional effects on outcomes will be reported in a future analysis.

To our knowledge, our study is among the first to use penalized regression (e.g. lasso) techniques to evaluate the importance of SES variables. Socioeconomic status indices are typically constructed using either simple points-based systems based on expert opinion, or principal components analysis (PCA). Because PCA is weighted based on variance rather than on correlation with the outcome variable, it cannot be used to assess variable importance. While our points-based index outperformed the data driven techniques in prediction of cognitive outcomes, it is reassuring that data-driven approaches confirm the importance of the variables chosen based on expert opinion. Further, these data-driven approaches suggest a minimum adjustment set of SES variables that should be evaluated in settings similar to ours. Our study suggests that, at a minimum, studies evaluating cognitive function in children with HIV in urban settings similar to Lusaka should account for effects of wealth and maternal education, with more comprehensive models including measures of water access, electricity, and food security. Studies in other settings, especially in more rural areas, may need to investigate which SES variables have the strongest relationship to cognitive outcomes in those settings.

Cognitive function may be affected by a variety of factors among children with HIV, including effects of chronic inflammation, malnutrition, poor health, side effects of ART, and chronic stress.(Spring, 1995; Farhadian, Patel and Spudich, 2017; Thakur et al., 2019). Makhubele et al., 2016; Barlow-Mosha et al., 2017) Imaging studies have suggested that these cognitive effects are at least partially mediated through inflammation-mediated effects on brain development (Dean et al., 2019), though there is likely a complex interplay between multiple factors driving these effects. SES may affect a variety of these potential mediators by affecting access to health care, nutritious food, and education.

Our study is broadly in line with a number of other studies suggesting a strong relationship between SES and cognition in children with HIV. In the IMPAACT 1104s study, one of the largest studies to date of cognitive function among children with HIV, a comparable relationship between SESI and cognitive function was seen. (Boivin et al., 2018; Boivin et al 2019). Our study extends these findings to a broader age range, and further suggests that SES effects on cognition may differ between children with and without HIV. Our study is also supportive of prior studies that have found nutritional variables to be among the strongest predictors of cognitive function in children in Sub-Saharan Africa. (Adam Moser, Kevin Range, 2008; Kapetanovic et al., 2014; Meyer, 2014; Robertson et al., 2015). However, in this analysis we were not able to differentiate the effects of micronutrient deficiencies (e.g. iron deficiency) vs. macronutrient deficiencies, and this will be evaluated as the HANDZ study continues.

Limitations, bias, and generalizability

This study has several limitations. First, despite the relatively large sample size for a study of this type, the study was not powered to detect relatively uncommon mediators or interaction effects, and thus absence of a significant p-value in the mediation analysis should not be interpreted as absence of an effect. In addition, a weakness of the current study is a limited assessment of education quality as a mediator of cognitive outcomes. It is likely that the quality of education varies markedly according to socioeconomic status, but in the current study we were only able to ascertain whether children attended school and were in a public or private school. In future studies, some measure of education quality may provide an additional link between SES and cognitive outcomes. One additional limitation of this study is that several variables that were specified as likely to be important in our causal diagram were not able to be measured in the current study. For example, parental mental health is both likely to be affected by SES, and to have an effect on child mental health, but we did not have a meaure of parental mental health included as part the current analysis. We plan to address these issues in future studies. Finally, this study was conducted in a single referral center in the capital city of Lusaka, and it is unclear how well these measures of SES would perform in more rural areas. With these caveats, we would anticipate that the study would generalize well to other urban centers in Sub-Saharan Africa.

13.0. Conclusion:

SES is one of the strongest predictors of cognitive function in children with and without HIV in Zambia, with a stronger effect among children with HIIV. This effect is partially mediated through nutritional factors, with a smaller effect mediated through poorer physical health and inability to attend school. Given the prevalence of HIV among children in Sub-Saharan Africa, there is an urgent need for interventions to improve cognitive function in children with HIV. This study suggests potential interventions might include nutritional interventions and supportive services targeted towards children in lower SES groups.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Socioeconomic Status Index (SESI) by Cognitive Impairment Status, demonstrating significantly lower mean SES in participants with cognitive impairment (Mean SESI 5.7 vs. 4.7, p<0.001).

Table 2B.

Bivariable analysis of risk factors for cognitive impairment in HIV-exposed uninfected participants

| Variable | Impaired N= 35 | Unimpaired N=148 | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 12.2(3.4) | 12.0 (2.6) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.67 |

| Male sex (% male) | 24 (69%) | 63 (43%) | 2.9 (1.3–6.5) | 0.007 |

| Self-reported poor physical health (%) | 3 (9%) | 8 (5%) | 1.6 (0.4–6.8) | 0.46 |

| Not in school (%) | 2 (14%) | 9 (11%) | 1.4 (0.3–7.0) | 0.72 |

| SES Variables | ||||

| Low maternal education (<7 years) | 19 (55%) | 60 (41%) | 1.7 (0.8–3.7) | 0.14 |

| Low paternal education (<9 years) | 2 (7%) | 13 (10%) | 0.6 (0.1–3.0) | 0.57 |

| Median Possession Index (IQR) | 1 (0–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.04 |

| Food insecurity (%) | 101 (68%) | 25 (71%) | 1.2 (0.5–2.6) | 0.72 |

| Piped water in home (%) | 6 (17%) | 41 (28%) | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) | 0.20 |

| Electricity in home (%) | 22 (63%) | 111 (75%) | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | 0.15 |

| Flush toilet in home (%) | 5 (14%) | 15 (10%) | 1.5 (0.5–4.4) | 0.48 |

| Nutritional Markers | ||||

| Growth Stunting (%) | 19 (54%) | 14 (10%) | 11.1 (4.7–26.4) | <0.001 |

| Low weight for height (%) | 17 (49%) | 19 (14%) | 6.2 (2.7–14.1) | <0.001 |

| History of malnutrition (%) | 3 (9%) | 5 (4%) | 2.7 (0.6–11.7) | 0.20 |

| History of severe malnutrition (%) | 3 (5%) | 3 (2%) | 2.9 (0.47–18.1) | 0.25 |

All variables are displayed as n (%), mean (SD) or median (IQR)

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23NS117310. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported by grants from the University of Rochester Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH-funded program (P30 AI 045008), the University of Rochester School of Medicine, and the McGowan Foundation.

Footnotes

There are no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose for any authors related to this work.

REFERENCES

- Moser Adam, Range Kevin, and D. M. Y. (2008) ‘NIH Public Access’, Bone, 23(1), pp. 1–7. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams HR et al. (2019) ‘The HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders in Zambia (HANDZ) Study: Protocol of a research program in pediatric HIV in sub-Saharan Africa’, medRxiv, pp. 1–32. doi: 10.1101/19003590. [DOI]

- Anderson AM et al. (2015) ‘HHS Public Access’, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 69(1), pp. 29–35. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000532.Plasma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangirana P. et al. (2009) ‘Socioeconomic predictors of cognition in Ugandan children: Implications for community interventions’, PLoS ONE, 4(11). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buda A, Dean O, Adams HR et al. Neighborhood-Based Socioeconomic Determinants of Cognitive Impairment in Zambian Children With HIV: A Quantitative Geographic Information Systems Approach. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021; piab076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Buda A, Dean O, Adams HR et al. Neurocysticercosis Among Zambian Children and Adolescents With Human Immunodeficiency Virus: A Geographic Information Systems Approach. Pediatr Neurol. 2020; 102: 36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow-Mosha L. et al. (2017) ‘Universal antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected children: A review of the benefits and risks to consider during implementation: A’, Journal of the International AIDS Society, 20(1), pp. 1–7. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden DR and Meyer A. (2016) ‘Should the Frascati criteria for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders be used in children ?’, Neurology, 87, pp. 1–2. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0b013e318200d727.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone K. et al. (2012) ‘Defining neurocognitive impairment in HIV: Deficit scores versus clinical ratings’, Clinical Neuropsychologist, 26(6), pp. 894–908. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2012.694479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin MJ et al. (2018) ‘Neuropsychological performance in African children with HIV enrolled in a multisite antiretroviral clinical trial’, Aids, 32(2), pp. 189–204. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A. and Brew B. (2017) ‘HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders : recent advances in pathogenesis, biomarkers, and treatment [version 1 ; referees : 4 approved ] Referee Status ’:, 6, pp. 1–11. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.10651.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. et al. (2015) ‘Poorer Cognitive Performance in Perinatally HIV-Infected Children Versus Healthy Socioeconomically Matched Controls’, 60, pp. 1111–1119. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coscia J. et al. (2001) ‘Effects of home environment, socioeconomic status, and health status on cognitive functioning in children with HIV-1 infection’, Journal ofPediatric Psychology, 26(6), pp. 321–329. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/jpepsy/article-abstract/26/6/321/965429 (Accessed: 11 November 2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSO (2016) Living Conditions Monitoring Survey Report, Living Conditions Monitoring Branch, CSO, Zambia. Available at: http://www.zamstats.gov.zm/report/Lcms/2006-2010LCMSReportFinalOutput.pdf.

- Dean O. et al. (2019) ‘Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings associated with Cognitive Impairment in Children and Adolescents with Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Zambia’, Pediatric Neurology. Elsevier Ltd, (xxxx). doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Discacciati A, Bellavia A, Lee JJ, Mazumdar M, Valeri L. Med4way: a Stata command to investigate mediating and interactive mechanisms using the four-way effect decomposition. International of Epidemiology. 2019. Feb;48(1):15–20. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis R, Langford D. and Masliah E. (2007) ‘REVIEWS HIV and antiretroviral therapy in the brain : neuronal injury and repair’, 8(January), pp. 33–44. doi: 10.1038/nrn2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhadian S, Patel P. and Spudich S. (2017) ‘Neurological Complications of HIV Infection’. Current Infectious Disease Reports, pp. 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hardy D. et al. (2009) ‘The neuropsychology of HIV / AIDS in older adults The Neuropsychology of HIV / AIDS in Older Adults’, (March). doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9087-0. [DOI]

- Hicks Raymond and Tingley Dustin (2011) mediation: STATA package for causal mediation analysis

- Hoare J. et al. (2016) ‘Applying the HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder diagnostic criteria to HIV-infected youth’, Neurology, 87(1), pp. 86–93. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabuba N, Jr DRF and Heaton RK (2018) ‘Effect of Age and Level of Education on Neurocognitive Impairment in HIV Positive Zambian Adults’, 32(5), pp. 519–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandawasvika GQ, Gumbo FZ and Kuona P. (2016) ‘ClinMed’, 3(2), pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic S. et al. (2014) ‘Biomarkers and neurodevelopment in perinatally HIV-infected or exposed youth’, Aids, 28(3), pp. 355–364. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhubele TG et al. (2016) ‘Systemic Immune Activation Profiles of HIV-1 Subtype C-Infected Children and Their Mothers’, Mediators of Inflammation, 2016(Cvd), pp. 8–10. doi: 10.1155/2016/9026573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A. (2014) ‘Neurology and the Global HIV epidemic’, Semin Neurol, 34(1), pp. 70–77. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372344.Neurology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinaro M, Adams HR, Mwanza-Kabaghe S et al. Evaluating the Relationship Between Depression and Cognitive Function Among Children and Adolescents with HIV in Zambia. AIDS Behav. 2021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mwanza-Kabaghe S. et al. (2015) ‘Zambian Preschools: A Boost for Early Literacy?’, English Linguistics Research, 4(4), pp. 1–10. doi: 10.5430/elr.v4n4p1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pem D. (2015a) ‘Factors Affecting Early Childhood Growth and Development : Golden 1000 Days Advanced Practices in Nursing’, Journal of Advanced Practices in Nursing, 1(1), pp. 1–4. doi: 10.4172/2573-0347.1000101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pem D. (2015b) ‘Factors Affecting Early Childhood Growth and Development : Golden 1000 Days Advanced Practices in Nursing’, 1(1), pp. 1–4. doi: 10.4172/2573-0347.1000101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips N. et al. (2016) ‘HIV-associated cognitive impairment in perinatally infected children: A meta-analysis’, Pediatrics, 138(5). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson KR et al. (2015) ‘Neurocognitive impairment in diverse resource-limited settings: The international neurological study ACTG A5199 and A5271’, Topics in Antiviral Medicine.

- Schneider CL, Mohajeri-Moghaddam S, Mbewe EG et al. Cerebrovascular Disease in Children Perinatally Infected With Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Zambia. Pediatr Neurol. 2020; 112: 14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladoje M. (2017) ‘Estimating the growth elasticity of poverty in Zambia ‘, 15(July). [Google Scholar]

- Spring V. (1995) ‘HIV pathogenesis’, Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 59(S21B), pp. 179–247. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240590707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur KT et al. (2019) ‘Global HIV neurology: a comprehensive review’, AIDS (London, England), 33(2), pp. 163–184. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele TJ A unification of mediation and interaction: a 4-way decomposition. Epidemiology. 2014. Sep;25(5):749–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambian Ministry of Health (2017) ‘Zambia National Health Strategic Plan 2017 – 2021’, pp. 1–116. Available at: http://www.moh.gov.zm/docs/ZambiaNHSP.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Socioeconomic Status Index (SESI) by Cognitive Impairment Status, demonstrating significantly lower mean SES in participants with cognitive impairment (Mean SESI 5.7 vs. 4.7, p<0.001).