Abstract

Objectives

Family income is an important determinant of child and parental health. In Canada, cash transfer programs to families with children have existed since 1945. This systematic review aimed to examine the association between cash transfer programs to families with children and health outcomes in Canadian children (ages 0 to 18) as well as family economic outcomes.

Methods

We reviewed academic and grey literature published up to November 2021. Additional studies were identified through reference review. We included any study that examined children 0–18 years old and/or their parents, took place in Canada and reported Canada-specific data, and reported child, youth and/or parental health outcomes, as well as family economic outcomes. Risk of bias was assessed by two reviewers using a modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Synthesis

Our search yielded 23 studies meeting the inclusion criteria out of 7052 identified. Eight studies in total measured child health outcomes, including birth outcomes, child overall health, and developmental and behavioural outcomes, and four directly addressed parental health, including mental health, injuries, and obesity. Most studies reported generally positive associations, though some findings were specific to certain subgroups. Some studies also examined fertility and labour force participation outcomes, which described varying effects.

Conclusion

Cash transfer programs to families with children in Canada are associated with better child and parental health outcomes. Additional research is needed to evaluate the mechanisms of effects, and to identify which types and levels of government transfers are most effective, and target populations, to optimize the positive effects of these benefits.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.17269/s41997-022-00610-2.

Keywords: Child health, Policy, Economic, Socioeconomic factors

Résumé

Objectifs

Le revenu familial est un important déterminant de la santé infantile et parentale. Au Canada, des programmes de transferts monétaires aux familles avec enfants existent depuis 1945. Notre revue systématique visait à examiner l’association entre les programmes de transferts monétaires aux familles avec enfants et les résultats cliniques chez les enfants canadiens (0 à 18 ans), ainsi que les résultats économiques familiaux.

Méthode

Nous avons passé en revue la littérature spécialisée et la littérature grise publiées jusqu’en novembre 2021. D’autres études ont été répertoriées par une revue des références. Nous avons inclus toute étude portant sur les enfants de 0 à 18 ans et/ou leurs parents, menée au Canada, rapportant des données propres au Canada et rapportant les résultats cliniques d’enfants, de jeunes et/ou de parents, ainsi que les résultats économiques de familles. Le risque de biais a été évalué par deux évaluateurs à l’aide d’une échelle de Newcastle-Ottawa modifiée.

Synthèse

Sur les 7 052 études repérées dans notre recherche, 23 répondaient aux critères d’inclusion. En tout, huit études mesuraient les résultats cliniques d’enfants, dont les issues de la grossesse, la santé globale des enfants et les résultats développementaux et comportementaux, et quatre études portaient directement sur la santé parentale, dont la santé mentale, les blessures et l’obésité. La plupart des études faisaient généralement état d’associations positives, mais certaines constatations étaient spécifiques à certains sous-groupes. Quelques études portaient aussi sur la fécondité et la participation à la population active et décrivaient une diversité d’effets.

Conclusion

Les programmes de transferts monétaires aux familles avec enfants au Canada sont associés à de meilleurs résultats cliniques infantiles et parentaux. Il faudrait pousser la recherche pour évaluer les mécanismes des effets constatés et pour déterminer quels sont les types et les niveaux de transferts gouvernementaux qui sont les plus efficaces, ainsi que les populations cibles, pour optimiser les effets positifs de ces prestations.

Mots-clés: Santé de l’enfant, politique (principe), économie, facteurs socioéconomiques

Introduction

Children’s health and development are strongly related to family financial circumstances. Family poverty has been identified as an important predictor of adverse child outcomes (Blair & Raver, 2016; Oberg et al., 2016); its influence on child health and development is exerted both through direct reduction in material resources to meet basic needs such as food, shelter, education and health care, and by creating circumstances such as greater parental stress, which in turn are associated with poorer child health and developmental outcomes (Gershoff et al., 2007; Neckerman et al., 2016; Pascoe et al., 2016).

In the setting of family poverty, parents’ own health, including mental health, often suffers, as they face the stresses of trying to meet basic needs for the household under financial constraints, and because they may prioritize scarce household resources towards their children (Fitzsimons et al., 2017; Knowles et al., 2016; Sandel et al., 2018). Parental health is critical to child health as parents buffer the effects of low income on children (Blair & Raver, 2016) and, while there is a strong focus on reducing child poverty in policy and clinical interventions, the importance of promoting parental health cannot be overstated. When aiming to improve child health outcomes, it is important to recognize that parental stress and well-being are likely important intermediate factors in the pathway between poverty and child health and developmental outcomes, and that the stresses of poverty may be experienced uniquely by parents compared to adults without children, given their responsibilities towards their children (Lange et al., 2017).

A multitude of clinical and public health interventions have been developed to address the social and economic concerns of families (Gottlieb et al., 2017), targeting proximal and downstream consequences of poverty and low income, several of which have been specifically designed to benefit children. Beyond these more explicitly health-oriented interventions, there is increasing attention to the value of income transfers to families with children, which have the potential to directly address the root cause of child health consequences of poverty.

There has been some discussion in the economics literature around the types of cash transfers that are most effective (for example cash transfers vs. in-kind transfers, which directly provide goods or services a family may need) (de Oliveira, 2009). A previous systematic review examining the effects of income supplementation on infant health outcomes showed positive effects of certain cash transfer programs on outcomes such as birthweight and infant mortality (Siddiqi et al., 2018). The Manitoba Healthy Baby Prenatal Benefit is one Canadian example of a cash transfer intervention, which provides a prenatal cash benefit to expectant families, and has been shown to reduce income-related inequities in preterm birth, low birthweight, breastfeeding, and other perinatal and neonatal outcomes (Brownell et al., 2018; Brownell et al., 2016). Income supplementation is one policy strategy that has been used to mitigate the effects of poverty on the physical, mental, and behavioural health of children. Canada has had a federal policy of cash transfers to families since the family allowance program began in 1945, which has continued in various forms, including universal child benefits and income tax credits (Pentland et al., 2020). Most recently, the Canada Child Benefit (CCB) was introduced in 2016, and provides a tax-free, income-adjusted cash transfer to families with children (Canada Revenue Agency, 2017). Since the implementation of the CCB, there has been a gradual improvement in household income for families with children, accompanied by a reduction in child poverty (Statistics Canada, 2018).

Given that the stated goals of direct cash transfers often include promoting poverty reduction, female labour force participation, and fertility, as well as supporting the health of children and parents (Federal, Provincial and Territorial Ministers Responsible for Social Services, 2005), an evaluation of their impact on such outcomes is imperative, particularly in the context of Canada’s recent expansion of direct cash transfers in the form of the CCB. An understanding of the scope of evidence describing the effects of cash transfers, including the type and magnitude of transfer, on child and parental health, as well as family economic outcomes, can therefore help inform policymaking, particularly in the Canadian context of our current benefits programs, such as the CCB. A synthesis of this knowledge has become even more urgent in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, where family finances have become even more strained (Carroll et al., 2020). In this systematic review, we therefore aimed to examine the association between cash transfer programs and health outcomes in Canadian children (ages 0 to 18), as well as health and economic outcomes of their families.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic review of academic and grey literature. The protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO and can be accessed at www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd (registration number 165812). We made use of the population, intervention, control, and outcomes (that is, PICO) criteria to inform the search strategy. The study population included infants, children, and youth up to the age of 18. The main exposure of interest or intervention was cash transfer programs, including baby bonuses and child tax credits. Our intervention definition did not include social assistance or welfare, as these are standard government programs, and our interest was specific to cash transfers as additional policy interventions. The comparator included individuals who did not receive the benefit.

The main outcomes of interest were health and development outcomes for children and family economic outcomes. Though the main focus of this review was on child health outcomes, we chose to include family economic outcomes as well, as these are often the direct target of cash transfer policies, and on the pathway towards improved child health. The search strategy, including search terms, is presented in Supplement 1.

Parental health outcomes were reported as secondary outcomes when included in studies reviewed using the above search strategy, including in some studies that did not measure child health or family economic outcomes. Importantly, search terms did not include parents explicitly, and report of parental health outcomes should not be considered a part of the systematic review. Moreover, we decided to add this secondary outcome because parental health may be an additional target of cash transfer interventions aimed at children, and because parents play a critical role in ensuring child health and well-being(Gromada et al., 2020). We applied similar PICO criteria to parental health outcomes where applicable, and included studies measuring any health outcome, including outcomes that would be considered physical health outcomes of parents, such as fertility.

Our review was restricted to studies published in English and that took place in Canada. We did not include any restrictions on study design. We searched academic and grey literature databases from their inception to November 2021. Structured searches were undertaken in the following academic literature databases: EconLit, Social Sciences Citation Index, MedLine (Ovid), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ProQuest), and the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (EBSCO). Grey literature databases included the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and OpenGrey.

Titles and abstracts of retrieved studies were screened to identify studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria outlined above (EC, RK, MJ, CDO). Rayyan QCRI was used to manage references and to screen titles and abstracts (Ouzzani et al., 2016). Full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and independently assessed for eligibility (NZ, AF). Any disagreement over the eligibility was resolved through discussion with a final reviewer (CDO). After title, abstract, and full-text review, studies were included if they empirically measured the effects of policies or programs, which provided a direct cash transfer to families with children. Studies were excluded if they did not measure a direct cash transfer, baby bonus, or tax rebate, if they did not measure a child or parental health outcome, or family economic outcome, if they did not separate Canadian data from aggregate data, or if they were commentaries or syntheses of studies. We reviewed the citations of syntheses to ensure all relevant studies were captured.

Data extraction

One reviewer (NZ) extracted the data using a standardized abstraction form developed by the research team, and a second reviewer verified all data extraction (AF). Data abstracted included study characteristics, such as year of publication, author, journal/source, country, aim(s) of study, study type, study period, study population and sample size, main exposure/interventions, outcome measures, risk of bias, overall strength of evidence, and key findings.

Assessment of study quality

Methodological quality and risk of bias were assessed using a modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale to appropriately interpret quasi-experimental designs of many relevant studies. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was further modified by Siddiqi et al. (2018) for use in a similar systematic review, and permits an evaluation and comparison of studies from a variety of disciplines. The tool included the following questions, with one point for each affirmative response: (1) Does the study draw on a representative and randomized sample of observations? (2) Does the study use a direct measure of policy/program exposure? (3) Does the study describe the characteristics of both exposed and unexposed groups? (4) Does the study control for observed confounders? (5) Does the study control for unobserved confounders? (6) Does the study test the robustness of reported statistical estimates? Similar to Siddiqi et al., study quality was classified into high (score of 5–6), medium (3–4), and low (1–2) (Siddiqi et al., 2018).

Results

Study selection

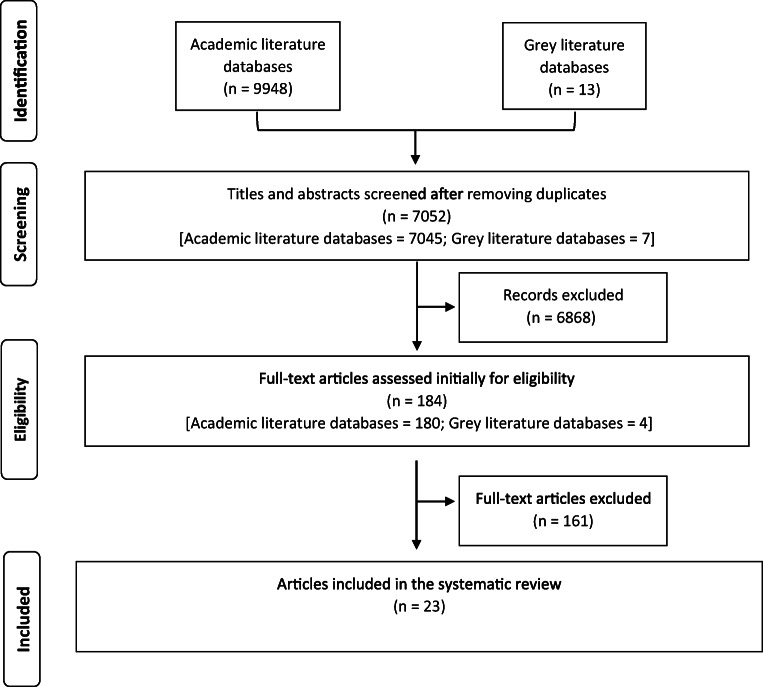

Figure 1 is a PRISMA diagram showing the inclusion and exclusion of studies through this review. Our initial literature search yielded 9948 studies from the academic literature and 13 studies from the grey literature. After all citations were merged and duplicates were removed, our search produced 7052 unique records, of which 184 were assessed for eligibility. Our final sample consisted of 23 studies, 8 measuring child health outcomes, of which 6 addressed child outcomes only. The remaining 17 studies measured family health and economic outcomes, or a combination of child and family outcomes. Studies are summarized in Table 1. While there were no time restrictions on our searches, our earliest study was published in 1996.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram depicting studies selected for inclusion

Table 1.

Synthesis of included studies

| Author | Region | Program details | Evaluation details | Findings | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child outcomes | |||||

| Brownell et al. (2018) | Manitoba |

Healthy Baby Prenatal Benefit Outcome: Perinatal and prenatal outcome |

Study design: Retrospective cohort study of propensity-score matched clinical intervention providing prenatal cash benefit. 10,031 mother-newborn pairs in each of the exposed and unexposed groups who were low income; 55,987 pairs who were not low income were also included to determine the effect of intervention on inequity Data sources: Health and social administrative data from Manitoba (PATHS), 2003–2010 |

Positive Receipt of benefit narrowed the gap between mothers who had low income and those who did not. Receipt of benefit was associated with narrowed gap in longer duration of breastfeeding, lower odds of preterm birth, lower odds of low birthweight |

5 |

| Brownell et al. (2016) | Manitoba |

Healthy Baby Prenatal Benefit Outcome: Perinatal and prenatal outcomes |

Study design: Cross-sectional study using propensity matching Data sources: Health and social administrative data 2003–2010 |

Positive Positive impact on all outcomes including low birth weight, preterm births, Apgar score, breastfeeding initiation, neonatal readmission, and newborn hospital length of stay |

6 |

| Enns et al. (2021) | Manitoba |

Healthy Baby Prenatal Benefit Outcome: Perinatal and prenatal outcomes; childhood vaccination rate; developmental vulnerability in kindergarten |

Study design: Cohort study using propensity matching restricted to First Nations women and children with low income, comparing mother-infant pairs who received a prenatal cash benefit (n=6103) to those who did not (n=2106) Data sources: Health and social administrative data 2003–2011 |

Positive Receipt of the benefit was associated with lower risk of low birthweight and prematurity, higher breastfeeding initiation, higher rates of childhood vaccination, and lower risk of developmental vulnerability |

5 |

| Lebihan and Mao Takongmo (2018) | 10 provinces |

Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB) Outcome: Child health and development |

Study design: Difference-in-differences study where the treatment group consists of children aged 5 or less and their parents and the control group children aged 6 or more (with no younger siblings) and their parents Data sources: NLSCY 1994–1995 (Cycle 1) through 2008–2009 (Cycle 8); and Survey of Young Children (SYC) SYC 2010–2011 |

Null – positive UCCB had no significant impact on children’s general health, with the exception of lower aggression scores, which were found after reform |

6 |

| Milligan and Stabile (2009) | Manitoba |

Canadian Child Benefit expansions and benefit expansions in Manitoba including allowing families to keep full social assistance income Outcome: Child behaviour |

Study design: Difference-in-differences study comparing Manitoba to the rest of Canada. 19,590 Canadian families with children 0–5 years Data sources: Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID), 1999–2005; National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY), 1998–1999 to 2004–2005;post-period2002–2003 and 2004–2005 |

Null to positive No difference found overall Among families with low education, exposed group showed higher motor and social development scores, lower aggression scores, better overall health for girls only |

5 |

| Struck et al. (2021) | Manitoba |

Healthy Baby Prenatal Benefit Outcome: Perinatal and prenatal outcomes; childhood vaccination rate |

Study design: Cohort study using propensity matching restricted to Métis women with low income, comparing mother-infant pairs who received a prenatal cash benefit (n=3702) to those who did not (n=1189) Data sources: Health and social administrative data 2003–2011 |

Mixed Positive: Receipt of the benefit was associated with lower risk of low birthweight and prematurity, increased childhood vaccination Negative: Receipt of the benefit was associated with higher risk of large-for-gestational age and neonatal readmission |

5 |

| Parental health only | |||||

| Daley (2017) | All provinces |

Universal Child Care Benefit Outcome: Parental health |

Study design: Repeated cross-sectionaldifference-in-differences study comparing mothers with children <6 years (eligible for UCCB) to mothers with children 6–12 years (ineligible). 26,886 mothers, 6273 of whom were lone parents Data sources: Microdata from the Canadian Community Health Survey, 2003 to 2008 |

Positive Better mental health and lower stress scores for eligible mothers compared to ineligible mothers |

6 |

| Kim (2014) | Quebec (compared with rest of Canada) |

Allowance for Newborn Children (ANC) Outcome: Fertility |

Study design: Empirical analysis using quasi-experimentaldifference-in-differences design. The 1991 and 1996 census files reported 345,351 families and 342,231 families, respectively Data sources: Census Public Use Microdata Files from 1991 and 1996 |

Null Age-adjusted exposure to the ANC policy was not associated with significantly higher completed fertility among women in Quebec compared with women in the rest of Canada. ANC was associated with higher fertility rate in younger age groups |

4 |

| Lebihan and Mao Takongmo (2019) | Canadian provinces |

Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB) Outcome: Parental Obesity |

Study design: Difference-in-differences study comparing mothers and fathers with children <6 years (eligible for UCCB) to mothers with children 6–12 years (ineligible) Data sources: Confidential micro-data files from the CCHS 2001–2014 |

Positive UCCB associated with decreases in BMI and the prevalence of overweight and obesity in mothers with young children. No impact on fathers |

5-6 |

| Milligan (2005) | Quebec (compared with rest of Canada) |

The Allowance for Newborn Children (ANC) Outcome: Fertility |

Study design: Quasi-experimentaldifference-in-differences study. The difference in the fertility of women in Quebec before and after the introduction of the ANC compared with the difference in fertility of women outside Quebec during the same period Data sources: Canadian 1991 and 1996 Census Public Use Microdata Files on Families |

Positive The responsiveness of fertility to a birth subsidy is estimated to be large—up to a 25% increase in fertility for families eligible for the full amount. A $1000 increase in first-year benefits is estimated to increase the probability of having a child by 16.9% |

5-6 |

| Parent and Wang (2007) | Quebec, Ontario, compared with rest of Canada |

Family Allowance Program Outcome: Fertility |

Study design: Difference-in-differences study Data sources: Canadian Census. The main datasets used come from the 1976, 1981, 1986, and 1991 Public Use Microdata Files on Families and the 1971, 1981, and 1991 Census Public Use Microdata Files on Individuals |

Overall null Short-term increase in fertility following introduction of program, ultimately offset by reduced fertility later in life |

5-6 |

| Redelmeier et al. (2012) | Ontario |

Ontario Child Benefit Outcome: Parental injury |

Study design: Repeated cross-sectional study, including total of 153,377 emergency department visits. Used universal health care databases to evaluate emergency department visits during specific days on which social benefit payments were made (child benefit distribution) relative to visits on control days over a 7-year interval (1 April 2003 to 31 March 2010 Data sources: Ontario health administrative data |

Positive Fewer emergency department visits per day on child benefit payment days than on control days. No significant differences were observed for the 7 days immediately before or the 7 days immediately after the child benefit payment |

5 |

| Economic outcomes only | |||||

| Baker et al. (2021) | Canada |

Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB) and Canada Child Benefit (CCB) Outcome: Household poverty, maternal labour force participation |

Study design: Difference-in-differences study comparing single mothers (exposed) to single women without children (unexposed) Data sources: Canadian Income Survey (2012–2017); Longitudinal Administrative Databank (2007–2018); Labour Force Survey (2012–2019) |

Positive to null After introduction of child benefit programs (UCCB and CCB), poverty decreased and after-tax income increased for the exposed group compared to unexposed group. However, no association between receipt of child benefits and labour force participation |

5-6 |

| Brown and Tarasuk (2019) | Canada |

Canada Child Benefit (CCB) Outcome: Food insecurity |

Study design: Difference-in-differences study comparing families with children (exposed) and families without children (unexposed); associations between receipt of CCB and food insecurity measured for three groups: any income (n=41,455), income less than median (n=18,191), and income less than low-income measure (n=7579) Data sources: 2015–2018 cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey |

Positive Receipt of CCB was associated with lower food insecurity, with the largest decrease among the group with low income |

5 |

| Hanratty and Trzcinski (2009) | Canada |

Extension of Canadian paid Family leave Outcome: Labour force participation |

Study design: Difference-in-differences study examining before and after implementation of extension Data sources: National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth from 1998 to 1999, 2000 to 2001, and 2002 to 2003 |

Generally positive Extension was associated with a notable increase in the proportion of mothers returning to work within 1 year after birth. Returns to work reverted to earlier levels once paid leave eligibility expired. Women with children of the age of 1 did not demonstrate a decrease in relative employment rates compared to those with children ages 3 to 4 |

5-6 |

| Ionescu-Ittu et al. (2015) | Nova Scotia, Quebec, Alberta, British Columbia, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut |

Universal child care benefit (UCCB) Outcome: Food insecurity |

Study design: Difference-in-differences study comparing families with children <6 years (eligible for UCCB) to families with children > 6 years Data sources: Canadian Community Health Survey 2001–2009 |

Positive Families receiving UCCB were less likely to report food insecurity |

5-6 |

| Milligan and Stabile (2007) | Canadian provinces |

National Child Benefit (NCB) (including integration of child benefits with social assistance payments) Outcome: Labour force participation |

Study design: Difference-in-differences study comparing receipt and non-receipt of benefits. Using administrative data, the authors calculated the federal and provincial benefits available to each family in the data using a detailed tax and benefit simulator for the Canadian tax system Data sources: The Census Family and the Person files of the Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) for the years 1996–2000 |

Positive Integration of benefits led to higher labour force participation among exposed participants |

5-6 |

| Tarasuk et al. (2019) | Ontario |

Eligibility for Ontario Child Benefit (OCB) based on calculated after-tax income Outcome: Food insecurity |

Study design: Repeated cross-sectional study to measure changes in household food insecurity in Ontario after the introduction of the 2007 Ontario Child Benefit and the 2008 implementation of the province’s poverty reduction strategy Data sources: Five cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey 2005 to 2014; Master files of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) |

Positive Prevalence of household food insecurity declined among families eligible for the OCB following its introduction |

4 |

| Woolley (1996) | Canada |

1993 child tax benefit reforms, including earned income supplement Outcome: Labour force participation |

Study design: Microsimulation analysis Data sources: Social Policy Simulation Database/Model (SPSD/M) developed by Statistics Canada 1992–1993; 10 qualitative interviews |

Positive but small Tax reforms led to minimal effects on labour force participation of families (mostly among lower-middle income families) |

3-4 |

| Multiple outcome categories | |||||

| Ang (2015) | Quebec (compared with rest of Canada) |

Quebec Parental Insurance Program (parental leave benefits, and a series of cash-transfer fertility incentives) Outcomes: Fertility, labour force participation |

Study design: Difference-in-differences study Data sources: Confidential versions of the Canadian Census and the Labour Force Surveys on-site at Statistics Canada, census data 1986–2011 |

Generally positive Higher parental leave benefits increased the birth rate and labour supply among women of childbearing age; cash transfer fertility incentives only slightly increased birth rates and decreased female labour supply |

5-6 |

| McNown and Ridao-Cano (2004) | Canada |

Child benefits Outcomes: Fertility, female labour force participation |

Study design: Economic empirical time-series analysis Data sources: Historical Statistics of Canada (Statistics Canada) for the period 1947–1963, OECD Labor Force Statistics for the period 1964–1999. Social Security Statistics (Human Resources Development Canada). Social Security Statistics (Human Resources Development Canada) |

Overall, null to positive but small relative effect sizes Child benefit policies led to small changes in fertility and female labour force participation |

3 |

| Milligan and Stabile (2011) | All Canadian provinces |

Canada Child Tax Benefit (CCTB)—unconditional transfer National Child Benefit Supplement (NCBS) Outcomes: Child health, maternal mental health |

Design: Policy evaluation study. Benefits first simulated using Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics, then simulated benefits evaluated using National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth, Comprises approximately 108,000 observations over survey cycles Data sources: National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY), 1994–1995 to 2004–2005. Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics for simulation |

Positive Child benefit programs had positive effects on child test scores, maternal physical health, and maternal mental health (depression) Stronger effects on educational outcomes, and on physical health for boys and mental health outcomes for girls |

6 |

| Morris and Michalopoulos (2003) | British Columbia and New Brunswick |

Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP)— earnings supplement for parents who went off social assistance for full-time employment Outcomes: Parental employment, child health |

Study design: Randomized control trial; 1654 families and 2582 children in the program group and 1605 families and 2496 children in the control group Data sources: Participant surveys collected in November 1992 and March 1995. |

Positive Economic: SSP was found to increase employment and income for parents of children in every age group Child health at 36 months of follow-up: for children 5 years and under, the SSP had no effect; for children in the ages 6–11, the SSP was associated with better children’s cognitive functioning and overall parent-reported health. For adolescents, the SSP increased minor delinquency and substance use |

6 |

Data and methodologies employed

Most studies used government-managed administrative data, including census microdata and provincial health administrative data (Brownell et al., 2018; Brownell et al., 2016; Enns et al., 2019; Kim, 2014; McNown & Ridao-cano, 2004; Milligan, 2005; Parent & Wang, 2007; Redelmeier et al., 2012; Struck et al., 2021; Woolley et al., 1996) or national surveys, such as the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (Hanratty & Trzcinski, 2009; Lebihan & Mao Takongmo, 2018; Milligan & Stabile, 2011), the Canadian Community Health Survey (Brown & Tarasuk, 2019; Daley, 2017; Ionescu-Ittu et al., 2015; Lebihan & Mao Takongmo, 2019; Tarasuk et al., 2019), or the Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (Milligan & Stabile, 2007, 2011). These studies frequently used difference-in-differences methods (Ang, 2015; Baker et al., 2021; Brown & Tarasuk, 2019; Daley, 2017; Hanratty & Trzcinski, 2009; Ionescu-Ittu et al., 2015; Kim, 2014; Lebihan & Mao Takongmo, 2018; Lebihan & Mao Takongmo, 2019; Milligan, 2005; Milligan & Stabile, 2007, 2011; Parent & Wang, 2007), time-series analyses (McNown & Ridao-cano, 2004), or cross-sectional (Brownell et al., 2016), repeated cross-sectional (Redelmeier et al., 2012; Tarasuk et al., 2019), or retrospective cohort (Brownell et al., 2018; Enns et al., 2019; Struck et al., 2021) designs to compare exposed individuals or populations to those unexposed to the intervention. Two studies simulated the effects of cash transfers using administrative or survey datasets (Milligan & Stabile, 2011; Woolley et al., 1996). One study included a randomized controlled trial (Morris & Michalopoulos, 2003). To account for confounding, propensity-score matching (Brownell et al., 2018; Brownell et al., 2016; Enns et al., 2019; Struck et al., 2021) was employed in some cases.

Outcomes

Child health outcomes

We identified eight studies that measured child health outcomes. Four studies examined the effect of a prenatal cash transfer on perinatal and infant outcomes and reported that a prenatal cash benefit was associated with better outcomes, including lower rates of low birthweight and preterm birth and longer breastfeeding duration (Brownell et al., 2018; Brownell et al., 2016). Four studies addressed child development, mental health, or behaviour outcomes, as well as overall measures of well-being. All reported a positive effect of cash transfers, though some positive findings were restricted to certain subgroups or specific outcome categories, such as certain age categories or domains of developmental or behavioural scales (Lebihan & Mao Takongmo, 2018; Milligan & Stabile, 2011; Milligan & Stabile, 2009). Four studies measured birth outcomes, including preterm birth, birth weight, and hospital stays in the newborn period, and reported protective effects of an unconditional cash transfer (Brownell et al., 2018; Brownell et al., 2016). Two of these studies were specific to First Nations (Enns et al., 2021) or Métis (Struck et al., 2021) women and their children. One study measured the effects of universal child care benefit (UCCB) on child health, and found beneficial effects only on child aggression scores (Lebihan & Mao Takongmo, 2018). Notably, the design of this study compared children 5 years of age and younger (treatment), who would have been eligible for UCCB, to children 6 years of age and older (control), who had only school-age children and would not have been eligible. The final study measured development and overall health among children 0–5 years of age, and reported no difference overall (Milligan & Stabile, 2009). However, subgroup analyses found that among families with lower parental education, the exposed group showed higher motor and social development scores and lower aggression scores (Milligan & Stabile, 2009). None reported negative effects.

Family economic outcomes

We identified ten studies that measured parent economic outcomes. Five studies measured financial outcomes. One found that an earnings supplement for parents who went off of social assistance for employment was associated with increased employment and income (Morris & Michalopoulos, 2003), and another found that receipt of UCCB or CCB was associated with reduction in household poverty and increase in after-tax income (Baker et al., 2021). Three other studies reported that cash transfers in the form of child benefits were associated with decreases in household food insecurity (Brown & Tarasuk, 2019; Ionescu-Ittu et al., 2015; Tarasuk et al., 2019). Five studies measuring economic outcomes measured parental labour force participation and reported overall null to positive associations (Ang, 2015; Baker et al., 2021; Hanratty & Trzcinski, 2009; McNown & Ridao-cano, 2004; Milligan & Stabile, 2007; Morris & Michalopoulos, 2003). Two studies examining the effects of paid parental benefits reported that these decreased maternal labour force participation during the time benefits were paid (Ang, 2015; Hanratty & Trzcinski, 2009), though one study reported that mothers returned to work once paid leave expired, and that there were similar employment rates between women with children at 1 year of age and women with children at 3 to 4 years of age (Hanratty & Trzcinski, 2009). One study examined the integration of child benefits with social assistance. They found that subtracting child benefits from social assistance reduced the tax burden of returning to work for low-income working single mothers. This reduced tax burden was associated with a decline in social assistance receipt among single mothers and increased labour force participation (Milligan & Stabile, 2007).

Secondary outcomes: family health

Our search identified seven studies that measured parental health outcomes independent of child health economic outcomes. Two studies addressed parental mental health and reported that cash transfers were associated with better parental mental health outcomes (Daley, 2017; Milligan & Stabile, 2011). One study reported that cash transfers were associated with lower overweight and obesity among mothers of young children, but not fathers (Lebihan & Mao Takongmo, 2019). A further study reported that parents had fewer emergency department visits for injuries on the day of the cash transfer (Redelmeier et al., 2012). The remaining parental health studies measured fertility independently (Kim, 2014; Milligan, 2005; Parent & Wang, 2007), or in combination with maternal labour force participation (Ang, 2015; McNown & Ridao-cano, 2004). Fertility studies with long-term follow-up primarily evaluating the Quebec Family Allowance Program reported increases in fertility among younger women (Kim, 2014) or shortly after the program was initiated (Parent & Wang, 2007), but these increases were offset by decreases in fertility later in life, leading to a null effect overall.

Exposure/interventions

This review reported a variety of intervention types, though all but one (a randomized controlled trial) represented a form of unconditional government cash transfer. Multiple studies looked specifically at cash transfers in pregnancy or in the newborn period (Ang, 2015; Brownell et al., 2018; Brownell et al., 2016; Kim, 2014; Milligan, 2005; Parent & Wang, 2007). These have been evaluated in terms of how they may promote maternal and infant health among families with low income, as in the case of Manitoba’s Healthy Baby Prenatal Benefit (Brownell et al., 2018; Brownell et al., 2016; Enns et al., 2019; Struck et al., 2021), or how they may promote fertility, as in the case of the Quebec Alliance for Newborn Children (Ang, 2015; Kim, 2014; Milligan, 2005; Parent & Wang, 2007). Multiple studies also evaluated national-level benefits, including the Universal Child Care Benefit (Baker et al., 2021; Daley, 2017; Ionescu-Ittu et al., 2015; Lebihan & Mao Takongmo, 2018; Lebihan & Mao Takongmo, 2019), which was a universal benefit paid per child to all families with children under 6 years of age, and the Canada Child Benefit (Baker et al., 2021; Brown & Tarasuk, 2019; Milligan & Stabile, 2011), National Child Benefit (Milligan & Stabile, 2007), and other national-level income-based child benefits (McNown & Ridao-cano, 2004; Tarasuk et al., 2019; Woolley et al., 1996). One study, the only one which was not a government transfer and was a conditional transfer, described the effects of the Self-Sufficiency Project. This was a randomized controlled trial undertaken in collaboration with the governments of British Columbia and New Brunswick, which provided a sizable earnings supplement of up to thousands of dollars per month for parents going off social assistance for full-time employment (Morris & Michalopoulos, 2003).

Study quality and risk of bias

Studies were generally of high quality (see scores in Table 1). Sixteen studies received risk of bias assessment scores of 5 or 6, and four received scores of 3 or 4 (Kim, 2014; McNown & Ridao-cano, 2004; Tarasuk et al., 2019; Woolley et al., 1996). Reasons for studies receiving lower assessment scores (indicating higher risk of bias) included not using a direct measure of the policy or intervention, not accounting for or addressing unobserved confounding, or not including descriptive characteristics of exposed and unexposed groups.

Discussion

Over the last several decades, several cash transfer programs for families with children in Canada have been introduced at the local, provincial, and national levels. This systematic review identified 20 studies that examined the effects of these programs on children and families with low-income and have reported consistently positive effects between receipt and child/families outcomes, with the evaluation of direct downstream financial effects of cash transfers showing that cash transfers may be able to improve family financial outcomes that are on the pathway between low income and poorer child health outcomes. Although not the main focus of this review, cash transfer programs tied to fertility were also found to be effective in increasing births. Programs designed to promote labour force participation had more nuanced effects.

Our review found that most studies examining the association between cash transfer programs and child health outcomes showed positive associations, extending the results of Siddiqi et al. who found that cash transfers improved infant health outcomes in the first year of life (Siddiqi et al., 2018). The evaluation of Manitoba’s Healthy Baby Prenatal Benefit, a cash transfer with the explicit goal of improving child and maternal health outcomes, found both positive effects of the benefit as well as a narrowing gap between mothers who did and did not have low income in terms of outcomes including low birthweight, preterm birth, breastfeeding initiation, and duration of breastfeeding (Brownell et al., 2018). Other studies examining federal cash transfers in the form of child benefits focused primarily on child behaviour and development; while findings were generally positive, for certain studies this was specific to certain outcomes or subgroups. It is challenging to evaluate a variety of health, developmental, and cognitive outcomes throughout childhood, and relationships between income and these outcomes are evidently complex. While perinatal outcomes are clearly associated with income, with pathways well established, these outcomes may be more difficult to capture consistently throughout childhood. Nevertheless, it is notable that all studies of child health outcomes found some positive associations.

Certain findings of this review highlight factors that may be considered in design and implementation of cash transfer programs. One important consideration is the timing of child benefits. It is notable that government cash transfers, which demonstrate benefits for child health outcomes, such as the Canadian Child Benefit, are delivered following a child’s birth. Evidence from the Manitoba Healthy Baby Prenatal Benefit suggests that prenatal cash transfers show promise for improving outcomes from the prenatal period and through childhood. As poverty is associated with adverse prenatal and perinatal outcomes, and these outcomes may translate into poorer health and developmental trajectories through the life course, earlier provision of government benefits may be worthwhile to reduce the effects of poverty on child health. As evidence supports these early life health outcomes as meaningful to long-term child health and development (Campbell et al., 2014), intervening directly on income shows a promising avenue towards supporting health through the life course. Additionally, while benefits of certain targeted interventions (such as in the prenatal period) have been shown in this review, there are likely other groups that may show differential, or greater, benefits from cash transfers. For example, Milligan and Stabile found a significant positive effect of benefits expansion on child development only among children in households with low parental education (Milligan & Stabile, 2011). Similarly, there may be differential effects by income or other characteristics, which could inform implementation of cash transfer policies.

Studies examining labour force participation evaluated different types of interventions, and therefore had differing and more nuanced findings. Two studies examining magnitude of paid parental leave benefits reported increases in labour supply among women of childbearing age (Ang, 2015) or no long-term change (Hanratty & Trzcinski, 2009). Studies of federal-level child benefits reported varying findings. One study evaluating the integration of child benefits with provincial social assistance, a program which reduced the “income wall” for labour force participation among mothers receiving social assistance, reported that this integration was associated with reduced social assistance receipt and increased labour force participation (Milligan & Stabile, 2007). Given the recent changes in child benefit administration in Canada with the addition of the Canada Child Benefit, it would be meaningful to see updated evaluations of new programs on this outcome that has multiple complex determinants.

Studies of family health, our secondary outcome, fell into two main groups. First, there were four studies that examined maternal mental health (Daley, 2017; Milligan & Stabile, 2011), parental obesity (Lebihan & Mao Takongmo, 2019), and parental injury (Redelmeier et al., 2012). All of these studies showed positive associations between cash transfer programs and better health outcomes. There are several possible mechanisms of these effects. Cash transfers may increase available income to spend on behavioural changes that reduce obesity, or pay directly for clinical interventions to promote health that are not universally covered by the health care system in Canada, such as psychotherapy, certain pharmacologic treatments, or physical activities (Sanmartin et al., 2014). Alternatively, it is possible that cash transfers reduce the stress of low income on parents, in turn improving stress-related outcomes (Cohen, 1980; Jensen et al., 2014; Sinha & Jastreboff, 2013). The second parental health outcome examined was fertility. Fertility decisions are complex and nuanced, and we recognize that programs that measure fertility may not have been designed to promote parental health. Future research should seek to explicitly examine the impact of cash transfer programs on parental health as well as fertility as this was not the intention of this review and there is likely more research on this topic, which may be of interest to decision makers.

Our study has several strengths. By integrating findings across child health and parental health and economic outcomes, we captured the full scope of common targets of cash transfer policies and included outcomes in infants, children, and youth up to the age of 18, building on the previous literature. Focusing specifically on cash transfers in Canada enhances the policy relevance of this review, as well as its timeliness given recent and ongoing changes to the Canada Child Benefit. Our study examined academic and grey literature across health sciences, social science, and economics literature to capture a breadth of the literature. Our review captured high-quality studies using similar methods of analysis, however, promoting confidence in our findings. Nonetheless, our study was subject to certain limitations. Because there were limited studies on each outcome, and the intervention types and outcomes varied, it was not feasible to conduct a meta-analysis to quantify the effects of cash transfer programs on child and parental health, or family economic outcomes, in Canada. Additionally, most studies reported on population-level improvements in health status among those receiving cash transfers; very few reported on whether or not cash transfers led to meaningful changes in household income or wealth. It is possible that meaningful studies were not included due to limitations in our search strategy. The risk of bias assessment tool, the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale as used by Siddiqi et al., was chosen to permit the examination of a heterogeneous body of literature; however, this required the tool to be general in its questions, which may have led to higher scores. It is important to consider that the outcomes examined in this review may be in the interests of families or the state or both in implementing the cash transfer interventions. The result of this review suggests that policies, which are implemented at the state level, may be of value to families as they affect the health of children and their parents. This value is likely different between families and across circumstances, and so it is challenging to infer in a systematic review. Finally, our review was specific to the Canadian social and health care context and may not be generalizable to other populations.

Conclusion

In summary, cash transfer programs to families with children in Canada are associated with better child and family health outcomes, and evidence particularly supports federal child benefits. Direct cash transfers, and income support policies in general, represent an important opportunity for governments to promote the health of children, including children from families with low income or experiencing poverty, with evidence supporting the benefits of prenatal cash transfers on birth outcomes as well as universal child benefits on maternal health. Additional research is needed to further evaluate the mechanisms through which cash transfers may improve child and parental health. Future research should also investigate which types of government transfers, including target populations and amount of supports and which combinations of supports in different contexts, are the most effective, as well as examine universal approaches such as universal basic income. This is particularly relevant as adaptations to existing benefits are implemented in order to optimize the positive effects of these benefits.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 35 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Edward Cho, RuthAnne Kavelaars, and Margaret Jamieson for their work in performing the initial literature search, compiling abstracts to be considered for inclusion, and undertaking the initial abstract review.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ang XL. The effects of cash transfer fertility incentives and parental leave benefits on fertility and labor supply: Evidence from two natural experiments. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2015;36(2):263–288. doi: 10.1007/s10834-014-9394-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M., Messacar, D., & Stabile, M. (2021). The effects of child tax benefits on poverty and labor supply: Evidence from the Canada Child Benefit and Universal Child Care Benefit. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, NBER Working Papers: 28556. Retrieved from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=1906224&site=ehost-livehttp://www.nber.org/papers/w28556.pdf

- Blair C, Raver CC. Poverty, stress, and brain development: New directions for prevention and intervention. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(3 Suppl):S30–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EM, Tarasuk V. Money speaks: Reductions in severe food insecurity follow the Canada Child Benefit. Prev Med. 2019;129:105876. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell MD, Chartier MJ, Nickel NC, Chateau D, Martens PJ, Sarkar J, et al. Unconditional prenatal income supplement and birth outcomes. Pediatrics. 2016;137(6):e20152992. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell M, Nickel NC, Chartier M, Enns JE, Chateau D, Sarkar J, et al. An unconditional prenatal income supplement reduces population inequities in birth outcomes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37(3):447–455. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell F, Conti G, Heckman JJ, Moon SH, Pinto R, Pungello E, Pan Y. Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science. 2014;343(6178):1478–1485. doi: 10.1126/science.1248429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canada Revenue Agency. Canada Child Benefit Statistics—2016–2017 Benefit Year. Government of Canada. 2017. <https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/programs/about-canada-revenue-agency-cra/income-statistics-gst-hst-statistics/canada-child-benefit-statistics/canada-child-benefit-statistics-2015-tax-year.html#toc10 <Accessed December 2020>.

- Carroll N, Sadowski A, Laila A, Hruska V, Nixon M, Ma DWL, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on health behavior, stress, financial and food security among middle to high income canadian families with young children. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2352. doi: 10.3390/nu12082352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Aftereffects of stress on human performance and social behavior: A review of research and theory. Psychol Bull. 1980;88(1):82–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley A. Income and the mental health of Canadian mothers: Evidence from the Universal Child Care Benefit. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:674–683. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, C. (2009). Good health to all: Reducing health inequalities among children in high- and low-income Canadian families. C.D. Howe Institute Commentary(288). Retrieved from https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:cdh:commen:288

- Enns JE, Chartier M, Nickel N, Chateau D, Campbell R, Phillips-Beck W, et al. Association between participation in the Families First Home Visiting programme and First Nations families' public health outcomes in Manitoba, Canada: A retrospective cohort study using linked administrative data. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e030386. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enns JE, Nickel NC, Chartier M, Chateau D, Campbell R, Phillips-Beck W, et al. An unconditional prenatal income supplement is associated with improved birth and early childhood outcomes among First Nations children in Manitoba, Canada: A population-based cohort study. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03782-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal, Provincial and Territorial Ministers Responsible for Social Services. (2005). Evaluation of the National Child Benefit Initiative Synthesis Report. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/esdc-edsc/documents/programs/child-benefit/papers/evaluation-report/eval_ncb.pdf.

- Fitzsimons E, Goodman A, Kelly E, Smith JP. Poverty dynamics and parental mental health: Determinants of childhood mental health in the UK. Soc Sci Med. 2017;175:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Aber JL, Raver CC, Lennon MC. Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Dev. 2007;78(1):70–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb LM, Wing H, Adler NE. A systematic review of interventions on patients' social and economic needs. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(5):719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromada, A., Rees, G., Chzhen, Y. (2020). Worlds of influence: Understanding what shapes child well-being in rich countries, Innocenti Report Card no. 16, UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti, Florence.

- Hanratty M, Trzcinski E. Who benefits from paid family leave? Impact of expansions in Canadian paid family leave on maternal employment and transfer income. Journal of Population Economics. 2009;22(3):693–711. doi: 10.1007/s00148-008-0211-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu-Ittu R, Glymour MM, Kaufman JS. A difference-in-differences approach to estimate the effect of income-supplementation on food insecurity. Prev Med. 2015;70:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen SK, Dumontheil I, Barker ED. Developmental inter-relations between early maternal depression, contextual risks, and interpersonal stress, and their effect on later child cognitive functioning. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(7):599–607. doi: 10.1002/da.22147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-I. R. (2014). Lifetime impact of cash transfer on fertility. Canadian Studies in Population, 41(1-2). 10.25336/P64S52

- Knowles M, Rabinowich J, Ettinger de Cuba S, Cutts DB, Chilton M. "Do you wanna breathe or eat?": Parent perspectives on child health consequences of food insecurity, trade-offs, and toxic stress. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(1):25–32. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1797-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange BCL, Dáu A, Goldblum J, Alfano J, Smith MV. A mixed methods investigation of the experience of poverty among a population of low-income parenting women. Community Ment Health J. 2017;53(7):832–841. doi: 10.1007/s10597-017-0093-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebihan L, Mao Takongmo C-O. The impact of universal child benefits on family health and behaviours. Research in Economics. 2018;72(4):415–427. doi: 10.1016/j.rie.2018.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lebihan L, Mao Takongmo CO. Unconditional cash transfers and parental obesity. Soc Sci Med. 2019;224:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNown R, Ridao-cano C. The effect of child benefit policies on fertility and female labor force participation in Canada. Review of Economics of the Household. 2004;2(3):237–254. doi: 10.1007/s11150-004-5646-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan K. Subsidizing the stork: New evidence on tax incentives and fertility. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2005;87(3):539–555. doi: 10.1162/0034653054638382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan K, Stabile M. The integration of child tax credits and welfare: Evidence from the Canadian National Child Benefit program. Journal of Public Economics. 2007;91(1):305–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2006.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan K, Stabile M. Do child tax benefits affect the well-being of children? Evidence from Canadian Child Benefit Expansions. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2011;3(3):175–205. doi: 10.1257/pol.3.3.175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, K., & Stabile, M. (2009). Child benefits, maternal employment, and children’s health: Evidence from Canadian Child Benefit Expansions. Am Econ Rev, 99(2), 128–132. [PubMed]

- Morris P, Michalopoulos C. Findings from the Self-Sufficiency Project: Effects on children and adolescents of a program that increased employment and income. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2003;24(2):201–239. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(03)00045-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neckerman KM, Garfinkel I, Teitler JO, Waldfogel J, Wimer C. Beyond income poverty: Measuring disadvantage in terms of material hardship and health. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(3 Suppl):S52–S59. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberg C, Colianni S, King-Schultz L. Child health disparities in the 21st century. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2016;46(9):291–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent D, Wang L. Tax incentives and fertility in Canada: Quantum vs tempo effects (Incitations fiscales et fécondité au Canada: Quantum vs Tempo) The Canadian Journal of Economics / Revue canadienne d'Economique. 2007;40(2):371–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.00413.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe JM, Wood DL, Duffee JH, Kuo A. Mediators and adverse effects of child poverty in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160340. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentland, M., Cohen, E., Guttmann, A., & de Oliveira, C. (2020). Maximizing the impact of the Canada Child Benefit: Implications for clinicians and researchers. Paediatrics & Child Health. 10.1093/pch/pxaa092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Redelmeier DA, Chan WK, Mullainathan S, Shafir E. Social benefit payments and acute injury among low-income mothers. Open Med. 2012;6(3):e101–e108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandel M, Sheward R, Ettinger de Cuba S, Coleman SM, Frank DA, Chilton M, et al. Unstable housing and caregiver and child health in renter families. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20172199. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartin C, Hennessy D, Lu Y, Law MR. Trends in out-of-pocket health care expenditures in Canada, by household income, 1997 to 2009. Health Rep. 2014;25(4):13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi A, Rajaram A, Miller SP. Do cash transfer programmes yield better health in the first year of life? A systematic review linking low-income/middle-income and high-income contexts. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(10):920–926. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Jastreboff AM. Stress as a common risk factor for obesity and addiction. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;73(9):827–835. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Income Survey, 2018. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200224/dq200224a-eng.htm <Accessed December 2020>.

- Struck S, Enns JE, Sanguins J, Chartier M, Nickel NC, Chateau D, et al. An unconditional prenatal cash benefit is associated with improved birth and early childhood outcomes for Metis families in Manitoba, Canada. Children and Youth Services Review. 2021;121:1. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk V, Li V, Dachner VNNA, Mitchell V. Household food insecurity in Ontario during a period of poverty reduction, 200U 2014. Canadian Public Policy. 2019;45:104–193. doi: 10.3138/cpp.2018-054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley F, Vermaeten A, Madill J. Ending universality: The case of child benefits. Canadian Public Policy / Analyse de Politiques. 1996;22(1):24–39. doi: 10.2307/3551747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 35 kb)