ABSTRACT

Background

The International Classification of Diseases eleventh edition (ICD-11) has recently included prolonged grief disorder (PGD), a diagnosis characterized by severe, persistent, and disabling grief. The text revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (DSM-5-TR) is scheduled to include a similar but distinct diagnosis, also termed PGD. Concerns have been raised that these new diagnoses are qualitatively different from both prior proposed diagnoses for pathological grief and each other, which may affect the generalizability of findings obtained with different criteria sets.

Objective

We conducted a content overlap analysis of PGDICD-11, PGDDSM-5-TR, and previous proposals for pathological grief diagnoses (i.e. PGD 2009; complicated grief (CG), PGD ICD-11 beta draft, persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD) per DSM-5).

Methods

Using the Jaccard’s Index, we established the degree of content overlap between core and accessory symptoms of PGDICD-11, PGDDSM-5-TR, and prior proposals for pathological grief diagnoses.

Results

Main findings are that PGDICD-11 and PGDDSM-5-TR showed moderate content overlap with each other and with most prior proposed diagnoses for pathological grief. PGDICD-11 and PGDDSM-5-TR showed the strongest content overlap with their direct predecessors, PGDICD-11 beta draft and PCBD, respectively.

Conclusions

Limited content overlap between PGDICD-11 and PGDDSM-5-TR and preceding criteria sets may threaten generalizability of past research on phenomenological characteristics of pathological grief to current criteria sets. Similarly, findings obtained with instruments to assess PGDICD-11 may not generalize to PGDDSM-5-TR and vice versa. Researchers should aim to determine under which circumstances criteria sets for PGD yield similar or distinct characteristics. Convergence of criteria sets for PGD remains an important goal for the future.

KEYWORDS: Grief, bereavement, diagnosis, DSM-5-TR, ICD-11, content overlap, prolonged grief disorder

HIGHLIGHTS

Content overlap analyses showed moderate overlap between symptoms of PGD per DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 and between these diagnoses and prior criteria sets.

We should establish when new criteria sets for PGD behave similarly or differently.

Convergence of PGD criteria sets is needed.

Short abstract

Antecedentes: La Decimoprimera Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades (CIE-11) ha incluido recientemente el Trastorno Por Duelo Prolongado (PGD por sus siglas en ingles), un diagnóstico caracterizado por un duelo severo, persistente e incapacitante. La versión revisada del Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales (DSM-5-TR) tiene agendado incluir un diagnóstico similar pero diferente, también llamado PGD. Ha existido preocupación de que ambos diagnósticos sean cualititativamente diferentes de aquellos propuestos previamente para duelo patológico y también entre sí, lo que puede afectar la posibilidad de generalización de los hallazgos obtenidos con cada conjunto de criterios diagnósticos.

Objetivo: Conducimos un análisis de solapamiento de contenido de los criterios diagnósticos del PGD de acuerdo a la CIE-11, del PGD de acuerdo al DSM-5-TR y de propuestas previas para diagnósticos de duelo patológico [como el PGD de Prigerson y colaboradores, publicado el 2009, Duelo complicado (CG por sus siglas en inglés) del borrador beta de la CIE 11, el Trastorno por Duelo Complejo Persistente (PCBD por sus siglas en inglés) del DSM-5].

Métodos: Usando el Índice de Jaccard, establecimos el grado de solapamiento del contenido entre los síntomas principales y accesorios de los criterios diagnósticos del PGD de acuerdo a la CIE-11, del PGD de acuerdo con el DSM-5-TR y de propuestas previas para diagnósticos de duelo patológico.

Resultados: Los resultados principales son que los criterios diagnósticos del PGD de acuerdo a la CIE-11 y PGD de acuerdo al DSM-5-TR mostraron un solapamiento de contenido moderado entre ellos y también con la mayoría de los diagnósticos de duelo patológico previamente propuestos. Ambos diagnósticos mostraron el mayor solapamiento de contenidos con sus predecesores directos, el Duelo Complicado del borrador beta de la CIE-11 y el PCBD respectivamente.

Conclusiones: el solapamiento limitado de contenidos entre los criterios diagnósticos del PGD de acuerdo a la CIE-11 y PGD de acuerdo al DSM-5-TR y los criterios precedentes pueden amenazar la generalización de investigación pasada de las características fenomenológicas del duelo patológico en los criterios diagnósticos actuales. En forma similar, los hallazgos obtenidos con instrumentos para evaluar el PGD de acuerdo a la CIE-11 pueden no ser generalizables al PGD de acuerdo al DSM-5-TR. Los investigadores debiesen determinar bajo qué circunstancias los criterios diagnósticos de PGD muestran características distintas o similares. La convergencia de los criterios diagnósticos de PGD sigue siendo una importante meta para el futuro.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Duelo, Pérdida, Diagnóstico, DSM-5 TR, CIE-11, Solapamiento de Contenido, Trastorno por Duelo Prolongado

Short abstract

背景: 国际疾病分类第 11 版 (ICD-11) 最近纳入了延长哀伤障碍 (PGD), 其特征是严重, 持续和致残的哀伤。精神疾病诊断和统计手册 5 (DSM-5-TR) 的文本修订计划纳入类似但不同的诊断, 也称为 PGD。有人担心这些新诊断与先前提出的病理性哀伤诊断和彼此之间存在质的不同, 这可能会影响使用不同标准集获得的结果的推广性。

目的: 我们对 PGDICD-11, PGDDSM-5-TR 和先前提出的病理性哀伤诊断 (即依据Prigerson etal., 2009 的PGD; 复杂性哀伤 (CG), PGD ICD-11 测试版草案, 依据 DSM-5 的持续性复杂丧亲症 (PCBD)) 进行了内容重叠分析,。

方法: 使用 Jaccard 指数, 我们确定了 PGDICD-11, PGDDSM-5-TR 以及先前提出的病理性哀伤诊断的核心和附加症状之间的内容重叠程度。

结果: 主要发现是 PGDICD-11 和 PGDDSM-5-TR 显示出中度的内容重叠, 并且与大多数先前提出的病理性哀伤诊断重叠。 PGDICD-11 和 PGDDSM-5-TR 分别与其直接前身 PGDICD-11 测试版草案和 PCBD 显示出最强的内容重叠。

结论: PGDICD-11 和 PGDDSM-5-TR 和先前的标准集之间有限的内容重叠可能会威胁到过去关于病理性哀伤现象学特征研究对当前标准集的推广性。同样, 使用评估 PGDICD-11 的工具获得的结果可能无法推广到 PGDDSM-5-TR。研究人员应着眼于确定在何种情况下为 PGD 设定的标准会产生相似或不同的特征。 PGD 标准集的收敛性仍然是未来的一个重要目标。

关键词: 哀伤, 丧亲, 诊断, DSM-5-TR, ICD-11, 内容重叠, 延长哀伤障碍

Dear Editor,

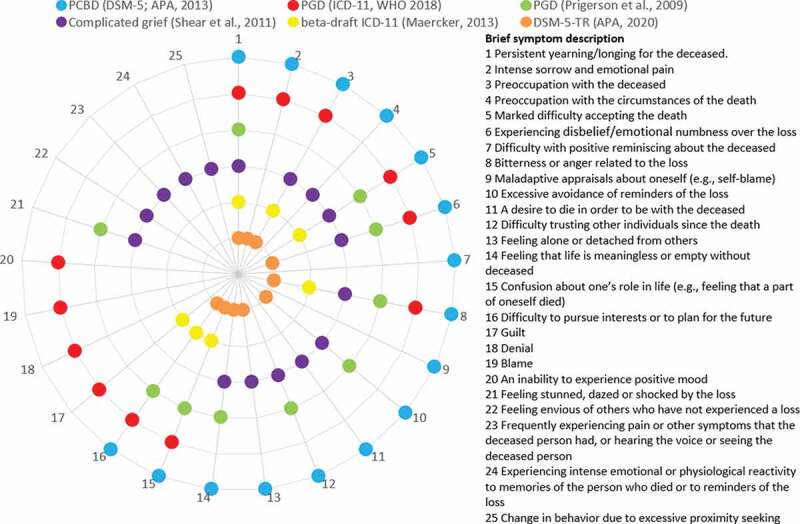

Over the past decades, there have been multiple attempts to define a diagnosis characterized by severe, persistent, and disabling grief, i.e. pathological grief. These proposed diagnoses have received different names, including complicated grief (CG: Shear et al., 2011), persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD: American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) and, most commonly, prolonged grief disorder (PGD, e.g. Prigerson et al., 2009, PGD2009; Maercker et al., 2013; PGDICD-11 beta draft). In 2018, a diagnosis termed PGD was formally added to the International Classification of Diseases eleventh edition (PGDICD-11, ICD-11: World Health Organization [WHO], 2018). A different diagnosis named PGD will be added to the text revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 in 2022 (PGDDSM-5-TR, DSM-5-TR: Boelen, Eisma, Smid, & Lenferink, 2020; Prigerson, Kakarala, Gang, & Maciejewski, 2021). Figure 1 displays core and accessory symptoms of all mentioned criteria-sets.

Figure 1.

Similarities and differences between five diagnostic criteria sets of pathological grief.

A concern regarding the development of new criteria-sets for pathological grief is that they are, as a rule, qualitatively different from preceding criteria-sets (e.g. Boelen & Prigerson, 2012; Djelantik et al., 2021; Eisma & Lenferink, 2017; Stelzer, Zhou, Maercker, O’Connor, & Killikelly, 2020). Criteria-sets differ in number of included symptoms, symptom content, and diagnostic algorithms (Eisma, Rosner, & Comtesse, 2020; Lenferink, Boelen, Smid, & Paap, 2021). Consequently, the phenomenological characteristics of different pathological grief criteria-sets vary. For example, PGDICD-11 has limited diagnostic agreement with prior proposed criteria-sets, such as PCBD and PGD2009 (e.g. Boelen & Lenferink, 2020; Boelen, Lenferink, Nickerson, & Smid, 2018; Comtesse et al., 2020; Cozza et al., 2020), although the extent of agreement partially depends on the chosen diagnostic algorithm (Eisma et al., 2020). Therefore, previous findings on important clinical issues, ranging from dimensionality of diagnoses to treatment efficacy, may not generalize to newer criteria-sets. Additionally, since PGDICD-11 and PGDDSM-5-TR also differ in symptom count, content, and diagnostic algorithms, findings obtained with one version of PGD may not generalize to the other.

Therefore, clarifying to what extent criteria-sets capture the same content and whether and when criteria-sets of pathological grief yield similar or different results appears important. The aim of the present contribution is to assess the comparability of different criteria-sets using a mathematical approach. Specifically, we will establish the extent to which the content of core and accessory symptoms in PGDICD-11, PGDDSM-5-TR, and preceding criteria-sets overlap. We derive these methods from Fried (2017), who used a similar approach to illustrate the limited content overlap between items from seven frequently used self-report measures of depression.

We estimated content overlap between criteria-sets using the Jaccard Index, a similarity coefficient for binary data ranging from 0 (no overlap among criteria-sets) to 1 (complete overlap). It is calculated with the following formula: J =s/(u1+u2+s), where J is the Jaccard Index, s is the number of items that two criteria-sets share, and u1 and u2 are the number of symptoms unique to each criteria set. Since there is no established guideline on categorizing the strength of overlap using the Jaccard Index, we will apply the rule by Evans (1996) for the correlation coefficient as an indicator: very weak 0.00–0.19, weak 0.20–0.39, moderate 0.40–0.59, strong 0.60–0.79, and very strong 0.80–1.0 (Fried, 2017).

Supplemental Table S1 shows the results. A first main finding is that there is moderate overlap between the most recent criteria-sets PGDICD-11 and PGDDSM-5-TR (J =0.47). PGDICD-11 shows the strongest overlap with the PGDICD-11 beta draft (J =0.58), whereas PGDDSM-5-TR shows the strongest overlap with PCBD (J = 0.63), illustrating that they most closely resemble their direct predecessors. Both PGDICD-11 and PGDDSM-5-TR show least overlap with CG (J =0.22 and 0.37, respectively). Overall, the mean overlap between PGDICD-11 and PGDDSM-5-TR with all other criteria-sets is moderate (J =0.41 and 0.48, respectively). CG stands out as the diagnosis showing the least overlap with all other criteria-sets (J =0.35), whereas PCBD shows most content overlap with other criteria-sets (J =0.49).

Overall, our analysis demonstrated modest content overlap between prior proposed criteria-sets and both PGDICD-11 and PGDDSM-5-TR. Moreover, the two newest criteria-sets showed limited content overlap with each other. These findings complement prior empirical research demonstrating differences between the characteristics of different criteria-sets for pathological grief (e.g. Boelen et al., 2020; Boelen & Lenferink, 2020; Comtesse et al., 2020; Cozza et al., 2020). Using a single validated instrument, such as the recently developed Traumatic Grief Inventory–Self Report Plus, to assess symptoms of different criteria-sets, may be instrumental to further elucidate when criteria-sets behave similarly or differently (Lenferink, Eisma, Smid, de Keijser, & Boelen, Lenferink, et al., 2022).

Together, results suggest that limited content overlap could partly explain differences in findings across different criteria-sets. Two courses of action may help reduce this problem of generalizability in the future. First, we should strive for greater convergence of future diagnostic criteria-sets with presently used criteria-sets (Lenferink et al., 2021). Second, since PGDICD-11 uses a descriptive diagnosis without a formal diagnostic algorithm, we could investigate which PGDICD-11 algorithm yields to the greatest convergence with past criteria-sets, and, more importantly, with PGDDSM-5-TR criteria (Eisma et al., 2020).

Some limitations warrant mention. First, this work is a mathematical exercise that complements but does not substitute empirical studies of similarities and differences between pathological grief criteria-sets. Second, we only compared core and accessory symptoms of criteria-sets. For example, we did not take into account differences in time criteria or diagnostic algorithms between proposed diagnoses. A third limitation is that for CG we split up some compound symptoms (e.g. ‘Frequent intense feeling of loneliness or like life is empty or meaningless without the person who died’ was separated into ‘loneliness’ and ‘feeling life is empty/meaningless’) because these symptoms were also separated in other criteria-sets (see Lenferink et al., 2021 for details). This may have led us to overestimate content overlap between CG and other criteria-sets. Fourth, one grief researcher assessed overlap between criteria sets (cf. Lenferink et al., 2021). Multiple assessors may have yielded more reliable and replicable classifications of symptoms.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our analyses have demonstrated suboptimal comparability in the content of past and current pathological grief criteria-sets. We have highlighted how this may result in problems of generalizability of findings obtained with past and current criteria-sets. This work illustrates the need for further convergence of diagnoses and empirical investigations of the similarities and differences between pathological grief diagnoses and related phenomenological characteristics.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen, P. A., Eisma, M. C., Smid, G. E., & Lenferink, L. I. M. (2020). Prolonged grief disorder in section II of DSM-5: A commentary. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1771008. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1771008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen, P. A., & Lenferink, L. I. M. (2020). Comparison of six proposed diagnostic criteria-sets for disturbed grief. Psychiatry Research, 285, 112786. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen, P. A., Lenferink, L. I., Nickerson, A., & Smid, G. E. (2018). Evaluation of the factor structure, prevalence, and validity of disturbed grief in DSM-5 and ICD-11. Journal of Affective Disorders, 240, 79–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen, P. A., & Prigerson, H. G. (2012). Commentary on the inclusion of persistent complex bereavement-related disorder in DSM-5. Death Studies, 36(9), 771–794. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2012.706982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comtesse, H., Vogel, A., Kersting, A., Rief, W., Steil, R., & Rosner, R. (2020). When does grief become pathological? Evaluation of the ICD-11 diagnostic proposal for prolonged grief in a treatment-seeking sample. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1694348. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1694348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozza, S. J., Shear, M. K., Reynolds, C. F., Fisher, J. E., Zhou, J., Maercker, A., … Ursano, R. J. (2020). Optimizing the clinical utility of four proposed criteria for a persistent and impairing grief disorder by emphasizing core, rather than associated symptoms. Psychological Medicine, 50(3), 438–445. doi: 10.1017/s0033291719000254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djelantik, A. M. J., Bui, E., O’Connor, M., Rosner, R., Robinaugh, D. J., Simon, N. M., & Boelen, P. A. (2021). Traumatic grief research and care in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1957272. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1957272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma, M. C., & Lenferink, L. I. M. (2017). Response to: Prolonged grief disorder for ICD-11: The primacy of clinical utility and international applicability. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup6), 1512249. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2018.1512249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma, M. C., Rosner, R., & Comtesse, H. (2020). ICD-11 prolonged grief disorder criteria: Turning challenges into opportunities with multiverse analyses. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 752. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J. D. (1996). Straightforward statistics for the behavioral sciences. Pacific Grove: Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, E. I. (2017). The 52 symptoms of major depression: Lack of content overlap among seven common depression scales. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenferink, L. I. M., Boelen, P. A., Smid, G. E., & Paap, M. C. (2021). The importance of harmonising diagnostic criteria-sets for pathological grief. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 219(3), 473–476. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenferink, L. I. M., Eisma, M. C., Smid, G. E., de Keijser, J., & Boelen, P. A. (2022). Valid measurement of DSM-5 persistent complex bereavement disorder and DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 prolonged grief disorder: The Traumatic Grief Inventory-Self Report Plus (TGI-SR+). Comprehensive Psychiatry, 112, 152281. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152281 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maercker, A., Brewin, C. R., Bryant, R. A., Cloitre, M., van Ommeren, M., Jones, L. M., and Reed, G. M. (2013). Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: proposals for ICD-11. World Psychiatry, 12(3), 198–206. https://doi:10.1002/wps.20057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson, H. G., Horowitz, M. J., Jacobs, S. C., Parkes, C. M., Aslan, M., Goodkin, K., … Maciejewski, P. K. (2009). Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Medicine, 6(8), e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson, H. G., Kakarala, S., Gang, J., & Maciejewski, P. K. (2021). History and status of prolonged grief disorder as a psychiatric diagnosis. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 17, 109–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-093600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear, M. K., Simon, N., Wall, M., Zisook, S., Neimeyer, R., Duan, N., … Keshaviah, A. (2011). Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM‐5. Depression and Anxiety, 28(2), 103–117. doi: 10.1002/da.20780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzer, E. M., Zhou, N., Maercker, A., O’Connor, M. F., & Killikelly, C. (2020). Prolonged grief disorder and the cultural crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2982. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2018). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.