Abstract

Cardiac dysfunction in heart failure (HF) and diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is associated with aberrant intracellular Ca2+ handling and impaired mitochondrial function accompanied with reduced mitochondrial calcium concentration (mito-[Ca2+]). Pharmacological or genetic facilitation of mito-Ca2+ uptake was shown to restore Ca2+ transient amplitude in DCM and HF, improving contractility. However, recent reports suggest that pharmacological enhancement of mito-Ca2+ uptake can exacerbate ryanodine receptor-mediated spontaneous sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release in ventricular myocytes (VMs) from diseased animals, increasing propensity to stress-induced ventricular tachyarrhythmia. To test whether chronic recovery of mito-[Ca2+] restores systolic Ca2+ release without adverse effects in diastole, we overexpressed mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) in VMs from male rat hearts with hypertrophy induced by thoracic aortic banding (TAB). Measurement of mito-[Ca2+] using genetic probe mtRCamp1h revealed that mito-[Ca2+] in TAB VMs paced at 2 Hz under β-adrenergic stimulation is lower compared with shams. Adenoviral 2.5-fold MCU overexpression in TAB VMs fully restored mito-[Ca2+]. However, it failed to improve cytosolic Ca2+ handling and reduce proarrhythmic spontaneous Ca2+ waves. Furthermore, mitochondrial-targeted genetic probes MLS-HyPer7 and OMM-HyPer revealed a significant increase in emission of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in TAB VMs with 2.5-fold MCU overexpression. Conversely, 1.5-fold MCU overexpression in TABs, that led to partial restoration of mito-[Ca2+], reduced mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species (mito-ROS) and spontaneous Ca2+ waves. Our findings emphasize the key role of elevated mito-ROS in disease-related proarrhythmic Ca2+ mishandling. These data establish nonlinear mito-[Ca2+]/mito-ROS relationship, whereby partial restoration of mito-[Ca2+] in diseased VMs is protective, whereas further enhancement of MCU-mediated Ca2+ uptake exacerbates damaging mito-ROS emission.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Defective intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and aberrant mitochondrial function are common features in cardiac disease. Here, we directly compared potential benefits of mito-ROS scavenging and restoration of mito-Ca2+ uptake by overexpressing MCU in ventricular myocytes from hypertrophic rat hearts. Experiments using novel mito-ROS and Ca2+ biosensors demonstrated that mito-ROS scavenging rescued both cytosolic and mito-Ca2+ homeostasis, whereas moderate and high MCU overexpression demonstrated disparate effects on mito-ROS emission, with only a moderate increase in MCU being beneficial.

Keywords: calcium-dependent ventricular arrhythmia, mitochondrial calcium uniporter, mitochondrial calcium uptake, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, ryanodine receptor

INTRODUCTION

Compromised mitochondrial function plays a key role in the pathophysiology of heart failure (HF), hypertrophy, diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), aging-related cardiac dysfunction, and genetic arrhythmia syndromes (1–6). During cardiac excitation and contraction, mitochondrial energy output in the form of ATP relies upon entry of Ca2+ into the mitochondrial matrix through the mitochondria Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) complex. This is especially important during stress, when heart function increases to meet metabolic demands of the body (7). Mito-[Ca2+] levels are reduced in HF and DCM ventricular myocytes (VMs), and restoration of mito-Ca2+ homeostasis was demonstrated to improve cardiac function and survival (8–10). However, under stress conditions, enhanced mito-Ca2+ uptake can lead to adverse effects, associated with accelerated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by mitochondria and perturbed intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis (4). Indeed, MCU genetic knock down or pharmacological inhibition exhibited antiarrhythmic effects reducing β-adrenergic agonist-induced ventricular tachyarrhythmias in hypertrophic rat hearts and mouse hearts with hypertension-induced cardiomyopathy (4, 11). However, other reports suggest that facilitation of mito-Ca2+ uptake can be protective as well, attenuating intracellular Ca2+-dependent arrhythmia trigger and reentry (9–12). This contradiction is yet to be reconciled.

Mitochondria are widely accepted as major ROS sources in cardiomyocytes. Accelerated mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species (mito-ROS) production has been established as a key factor underlying pathology in HF, infarct, DCM, aging, atrial fibrillation, and, more recently, in hereditary cardiac arrhythmia syndrome, i.e., catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) (5, 13–19). Several components of VM Ca2+ handling machinery are highly susceptible to oxidative modifications, including the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ ATPase (SERCa2a) and SR Ca2+ release channel, the cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2) (20). Oxidation of SERCa2a at Cysteine 674 significantly impedes Ca2+ reuptake into the SR contributing to cytosolic Ca2+ overload (21). Oxidation of RyR2 increases its activity, resulting in SR Ca2+ leak during diastole (20). Under β-adrenergic stimulation in conditions mimicking stress, increased RyR2 activity promotes the generation of spontaneous Ca2+ waves that underlie proarrhythmic disturbances in membrane potential, i.e., early or delayed depolarizations (EADs and DADs, respectively) (16, 22–24). Scavenging of mito-ROS has been shown to reduce arrhythmic risk in transgenic mouse model of lipotoxic cardiomyopathy (25), aging rat hearts (26), and a Guinea pig model of hypertrophy and HF (27). At the cellular level, application of mitochondrial-targeted scavenger mito-TEMPO restores cytosolic Ca2+ transient amplitude and reduces proarrhythmic spontaneous Ca2+ waves in diseased and aging hearts (15, 16, 22, 25, 28). Given that mito-ROS at least in part depends upon mito-[Ca2+], we aimed to test whether restoration of mito-Ca2+ levels by overexpressing MCU in VMs from rat hearts with hypertrophy induced by thoracic aortic banding (TAB) can restore the redox state and rescue defective Ca2+ homeostasis.

Our results demonstrate that complete mito-Ca2+ restoration by 2.5-fold MCU overexpression does not restore Ca2+ transient amplitude in TAB VMs exposed to β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol (ISO). Furthermore, the increase in mito-[Ca2+] measured using matrix-targeted biosensor mtRCamp1h was paralleled with 1) increased mito-ROS production measured using mitochondria-targeted H2O2 biosensors, 2) a lack of improvement in proarrhythmic spontaneous Ca2+ release, and 3) no restoration of SR Ca2+ content. On the contrary, partial restoration of mito-Ca2+ by 1.5-fold MCU overexpression in TABs was protective, reducing mito-ROS and improving cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis. In addition, mito-ROS scavenging with mitoTEMPO not only improved cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis reducing spontaneous Ca2+ waves but also restored mito-Ca2+ as well.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular Biology

The intramitochondrial Ca2+ biosensor mtRCamp1h was constructed by fusing cytochrome C oxidase subunit IV at the NH2-terminus of RCamp1h coding region (29), as described previously (4). The OMM-HyPer biosensor was constructed by fusing mAKAP1 followed by a linker to the NH2-terminus of pC1-HyPer-3 (30), as described previously. The plasmid encoding MLS-HyPer7 was a gift from Vsevolod Belousov (31). The G-CEPIA1er biosensor was a gift from Masamitsu Iino (32). We generated adenoviruses carrying biosensor constructs using the ViraPower Gateway expression system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Adenovirus encoding mouse MCU was kindly gifted by Dr. Jin O-Uchi, University of Minnesota Twin Cities.

Study Animals

All procedures involving animals were approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, Revised 2011). Male Sprague-Dawley rats with sham and TAB surgery were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Animals were shipped 5–7 days after TAB surgery, and acclimatized for 3–4 wk in The Ohio State University animal facility. Experiments were performed 4–5 wk after aortic banding procedure. Transthoracic B-mode and M-mode echocardiography of sham and TAB rats under isoflurane (3%–4%) was performed on a Vevo 3100 Imaging System (FujiFilm VisualSonics, Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada). A total of 27 sham and 28 TAB rats were used in this study, and VMs isolated from each animal were split for multiple experimental protocols.

Ventricular Myocyte Isolation and Primary Culture

Ventricular myocytes were obtained by enzymatic digestion as previously described (4). Rats were anesthetized with a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital solution (120 mg/kg) before the heart was rapidly removed. Hearts were immersed in cold Ca2+-free Tyrode’s solution (in mM: 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.0 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 5.6 glucose, pH 7.3). Hearts were then mounted on a Langendorff apparatus and retrogradely perfused through the aorta with Tyrode’s solution containing collagenase II (Worthington Biochemical Corp.) at 37°C for 16 min. Ventricles were minced and placed in a 37°C water bath shaker in collagenase solution. Myocytes were plated onto laminin-coated glass coverslips in 24-well dishes in serum-free medium 199 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 25 mmol/L NaHCO3, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 5 mmol/L creatine, 5 mmol/L taurine, 10 U/mL penicillin, 10 μg/mL streptomycin, and 10 μg/mL gentamycin (pH 7.3). Any unattached cells were removed by replacing the medium after 1 h. Myocytes were infected with adenoviruses at an MOI of 10 and were cultured at 37°C in 95% air and 5% CO2 for 36–44 h before analysis. For 2.5-fold MCU overexpression, myocytes were infected with MCU at an MOI of 10. For 1.5-fold MCU overexpression, myocytes were infected with MCU at an MOI of 5. Rat VMs maintain structural integrity including T-tubule organization and electrical properties for at least the first 48 h of culture (33).

Confocal Imaging

Laser scanning confocal imaging was performed using Leica SP8 dmi8 in x–y and linescan modes. Cultured myocytes were paced via field stimulation using extracellular platinum electrodes.

Standard pacing protocol for measurements using biosensors and indicators in rat VMs.

This standard pacing protocol was followed during assays using mtRCamp1h, MLS-HyPer7, and OMM-HyPer. Baseline myocyte fluorescence was recorded for 5 min (0–5 min of recording) under continuous perfusion with Tyrode’s solution containing 1 mM Ca2+ and β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol (50 nM). Myocytes were then field stimulated for 5 min at 2 Hz (5–10 min of recording). The same pacing protocol was followed for confocal imaging of Ca2+ transients, but line scans were recorded during the last minute of pacing. For experiments with mitoTEMPO, VMs were preincubated with mitoTEMPO (20 μM, Millipore Sigma) for 5 min before experimentation, and mitoTEMPO was included in the perfusion solution.

Confocal imaging of cytosolic Ca2+.

Myocytes were cultured for 36–44 h before imaging. A subset of TAB VMs was infected with adenovirus encoding mouse MCU. To measure cytosolic Ca2+, cultured rat VMs were loaded with Fluo-3 AM (Invitrogen) at room temperature for 10 min in Ca2+-free Tyrode’s solution, followed by an 8-min wash in Tyrode’s solution containing 1 mM Ca2+. Myocytes were perfused with Tyrode’s solution containing 1 mM Ca2+ at room temperature during recordings. Fluo-3 AM was excited at 488 nm and fluorescence emission was collected at 500–550 nm wavelengths in line scan mode at 200 Hz sampling rate. The pacing protocol was followed as aforementioned. High-dose caffeine (10 mM) was applied to assess SR Ca2+ content after the protocol. Cytosolic Ca2+ transient amplitude is presented as ΔF/F0, where F0 is basal fluorescence and ΔF = F − F0. The SR Ca2+ content is presented as ΔFcaff/ΔF0, where F0 is basal fluorescence and ΔFcaff = (Fcaff − F0)/F0.

Confocal imaging of mito-Ca2+.

Myocytes were infected with mtRCamp1h adenovirus ± MCU adenovirus and cultured for 36–44 h. Biosensor mtRCamp1h was excited using 543 nm line of HeNe laser and fluorescence emission was collected at 560–660 nm wavelengths, measured in the x–y mode and 400 Hz sampling rate. The pacing protocol was followed as aforementioned. After this protocol, VMs were washed in Ca2+-free Tyrode’s solution, before permeabilization with saponin (0.001%). The solution was replaced with an internal recording solution containing cytochalasin D (10 μM) and Ca2+ buffer EGTA (2 mM) to obtain minimum mtRCamp1h fluorescence. Maximum fluorescence was achieved by application of Ca2+ (20 μM). Using the equation mito-[Ca2+] = Kd × (F − Fmin)/(Fmax − F), where Kd of mtRCamp1h = 1.3 µM for Ca2+, fluorescence was converted to mito-[Ca2+] for each myocyte. Analysis parameters included baseline and peak mtRCamp1h mito-[Ca2+] (μM), the time to peak amplitude (s), and the rate of decay (s−1).

Confocal imaging of mito-ROS.

Myocytes were infected with OMM-HyPer or MLS-HyPer7 adenovirus ± MCU adenovirus, and cultured for 36–44 h before imaging. Biosensor OMM-HyPer was excited using 488 nm laser line and fluorescence collected at 500–550 nm. Biosensor MLS-HyPer7 was excited using 405 and 488 nm laser lines and fluorescence emission was collected at 520–540 nm wavelengths. Fluorescence was measured in the x–y mode at 400 Hz sampling rate. The pacing protocol was followed as aforementioned. After this protocol, minimum fluorescence was obtained by application of dithiothreitol (DTT, 5 mM), and maximum fluorescence (Fmax) was obtained by application of deoxythymidine diphosphate (DTDP, 200 µM). Data are presented as percentage of ΔF/ΔFmax, where ΔF = F − Fmin and ΔFmax = Fmax − Fmin. The time constant of caffeine transient decay was used as a measure of the leak by fitting fluorescence data to a monoexponential function.

Confocal imaging of intra-SR Ca2+.

Myocytes were infected with G-CEPIA1er adenovirus ± MCU adenovirus and cultured for 36–44 h before imaging (16). The biosensor was excited using 488 nm line of argon laser and fluorescence emission was collected at 500–550 nm, measured in x–y mode at 400 Hz sampling rate. Resting VMs were exposed to SERCa2a inhibitor thapsigargin (2 μmol/L) after 5 min in ISO, and fluorescence signal from G-CEPIA1er was monitored using confocal microscopy. The time constant of decay of G-CEPIA1er was used as a measure of the leak by fitting fluorescence data to a monoexponential function (13, 16). The SR Ca2+ store was depleted by application of high-dose caffeine (10 mmol/L) in Ca2+-free Tyrode’s solution.

Western Blot Analysis

To determine protein expression, intact sham and TAB rat VMs were cultured for 36–44 h. Myocytes were lysed in lysis buffer from Cell Signaling (Cat. No. 9803S), supplemented with phosphatase (Calbiochem, Cat. No. 524,625) and protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma, Cat. No. P8340). Samples (20–30 μg of proteins) were resolved on a 4%–20% gel via SDS‐PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with antibodies specific for proteins of interest (listed in Table 1) and subsequently probed with secondary antibody. Blots were developed with ECL (Bio‐Rad Laboratories) and quantified using ImageJ and Origin 8 software.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in this study

| Antibody | Company | Cat. No. | RRID | Dilution | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-Hsp60 | Cell Signaling | 12165T | AB_2636980 | 1:5,000 | (16) |

| Anti-GAPDH [6C5] mouse | Abcam | AB8245 | AB_2107448 | 1:10,000 | (16) |

| Anti-MCU | Millipore-Sigma | HPA016480 | AB_2071893 | 1:2,500 | (16) |

| Anti-NCX1 | Millipore-Sigma | AB3516P | AB_91488 | 1:2,500 | (34) |

| Anti-rabbit IgG(H + L), HRP | Promega | W4011 | AB_430833 | 1:5,000 | (16) |

| Anti-mouse IgG(H + L), HRP | Promega | W4021 | AB_430834 | 1:5,000 | (16) |

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of data was performed using Origin 8.0 (OriginLab Corp) or SAS (SAS Institute). All data are presented as means ± SE. Western blot data were analyzed using Student’s t test or one‐way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test. Data from isolated myocytes were analyzed using two level random intercept model as described by Sikkel et al. (35). Briefly, the model tests for data clustering at each cell isolation (heart level hierarchy) and perform significance testing adjusting for the amount of clustering. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were carried out using Tukey’s adjustment. P values are given to three decimal places, and values of *P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

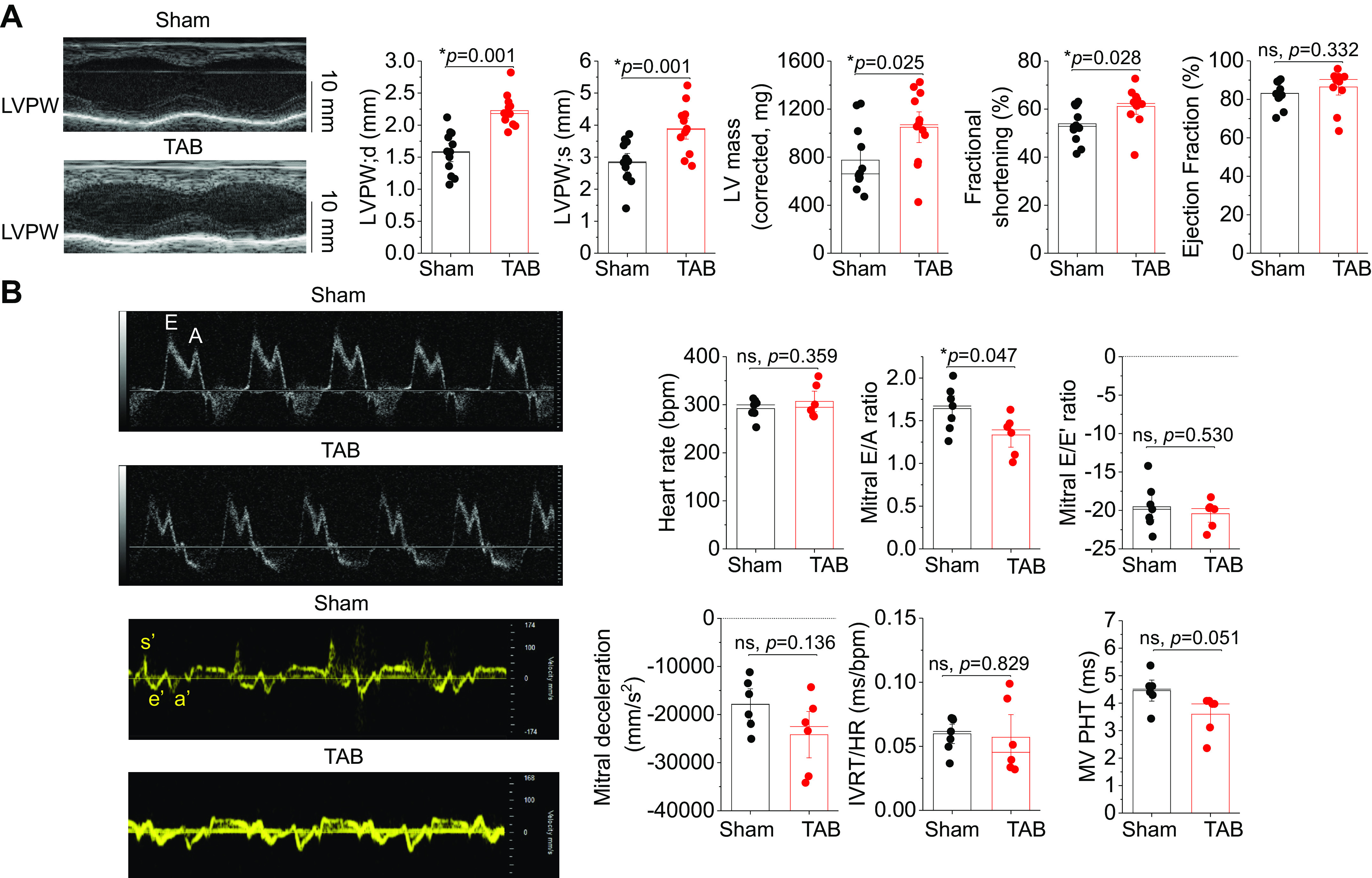

Echocardiography of Sham and TAB Rat Hearts

We first performed transthoracic B-mode and M-mode echocardiography on sham and TAB rats, 4–5 wk after aortic banding/sham procedure. At this stage, banding of the ascending aorta induces pressure overload and the development of cardiac hypertrophy (36–38). Indeed, M-mode echocardiography showed that the left ventricular posterior wall thickness was significantly increased in TAB rat hearts, both in systole and diastole, as is LV mass (Fig. 1A). Fractional shortening was significantly increased in hearts of TAB rats, whereas ejection fraction remained unchanged. Additional B-mode imaging was performed in the four-chamber-axis view to analyze to assess diastolic function. Mitral velocity in the early (E) and atrial contraction (A) phases of filling, along with mitral deceleration and isovolumetric relaxation time were obtained with pulse-wave Doppler. Tissue-Doppler imaging was used across the mitral annulus to obtain E′ and A′. This revealed a small but significant reduction in mitral E/A ratio (from ∼1.6 in shams to ∼1.2 in TABs, Fig. 1B). No other significant changes in diastolic measures including E/E′, isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT, normalized to heart rate), mitral deceleration, or mitral valve pressure half time (MV PHT) were observed. These data suggest that TAB rats were in an early, compensated stage of hypertrophy, progressing toward diastolic dysfunction (an E/A ratio of 1), with increased arrhythmic risk. Of note, we have previously demonstrated that 100% of ex vivo TAB rat hearts develop ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation compared with 15% of shams, when challenged with β-adrenergic agonist ISO (39).

Figure 1.

Echocardiographic phenotype of rats with thoracic aortic banding. A: representative M-mode echocardiography images of age-matched sham and TAB rat hearts, 4–5 wk after banding procedure. Data shown include left ventricular posterior wall (LVPW) both in diastole (LVPWd) and systole (LVPWs), LV mass, fractional shortening, and ejection fraction. Data are presented as means ± SE. n = 12 sham animals, n = 12 TAB animals. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test. B: representative B-mode and tissue Doppler echocardiography images of sham and TAB rat hearts. Data shown include heart rate, mitral E/A ratio, mitral E/E′ ratio, mitral deceleration, isovolumetric relaxation time normalized to heart rate (IVRT/HR), and mitral valve pressure half time (MV PHT). Data are presented as means ± SE. n = 7 sham rats, n = 6 TAB rats. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test. ns, not significant; TAB, thoracic aortic banding.

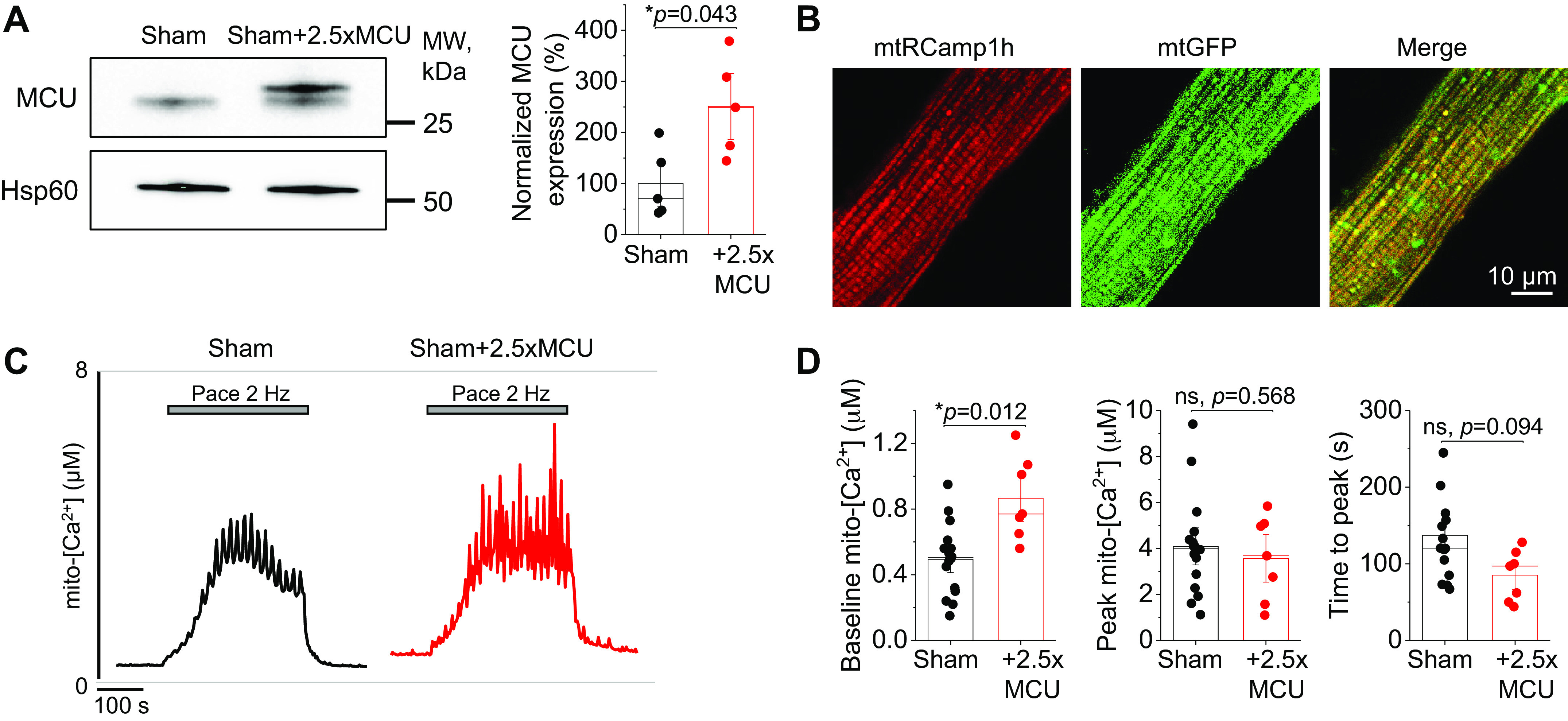

MCU Overexpression in Healthy Ventricular Myocytes Modulates Mito-[Ca2+] but Does Not Increase Maximum Load

To our knowledge, the effects of overexpressing MCU to modulate mito-[Ca2+] have yet to be studied in healthy myocytes. We therefore infected sham VMs with adenovirus encoding mouse MCU and cultured 36–44 h before experimentation. A representative Western blot and quantification showing 2.5-fold MCU overexpression are shown in Fig. 2A. To assess effects of MCU overexpression on mito-[Ca2+], we coinfected VMs with genetic probe mtRCamp1h, a matrix-targeted Ca2+ biosensor with a Kd ∼1.3 µM for Ca2+. Correct intracellular localization is demonstrated in Fig. 2B sham and sham+MCU VMs under β-adrenergic stimulation with ISO (50 nM) were recorded at baseline for 2 min, before pacing at 2 Hz for 5 min. Representative traces are shown in Fig. 2C. Quantification revealed that baseline mito-[Ca2+] was significantly increased in sham+MCU versus sham VMs, whereas peak mito-[Ca2+] remained at similar levels (Fig. 2D). This suggests that mito-[Ca2+] cannot be increased beyond maximum sham load achieved during pacing (∼4 µM) using this approach.

Figure 2.

MCU overexpression does not increased maximum mito-[Ca2+] in healthy myocytes. A: Western blots demonstrating overexpression (2.5-fold, 2.5×) of MCU in cultured sham rat VMs. Data were normalized to Hsp60 expression, and are presented as means ± SE. n = 5 sham animals, with VMs from each animal split into sham and sham + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. *P < 0.05, paired Student’s t test. B: representative confocal images of VM infected with mtRCamp1h and mtGFP, with a merged figure to demonstrate correct probe localization. C: representative traces of cultured sham and sham + 2.5×MCU VMs expressing Ca2+ biosensor mtRCamp1h. Myocytes were treated with isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM) for 5 min before pacing at 2 Hz for 5 min. Cells were then saponin permeabilized, treated with EGTA (2 mM) for minimum fluorescence, and Ca2+ (20 µM) to obtain maximum fluorescence. Signal was converted using equation mito-[Ca2+] = 1.3 × (F-min)/(max-F). D: means ± SE of baseline mito-[Ca2+], peak mito-[Ca2+], and time to peak. n = 5 sham animals, with VMs from each animal split into sham and sham + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. n = 16 sham VMs, n = 7 sham + 2.5×MCU VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter; mito-[Ca2+], mitochondrial calcium concentration; ns, not significant; VMs, ventricular myocytes.

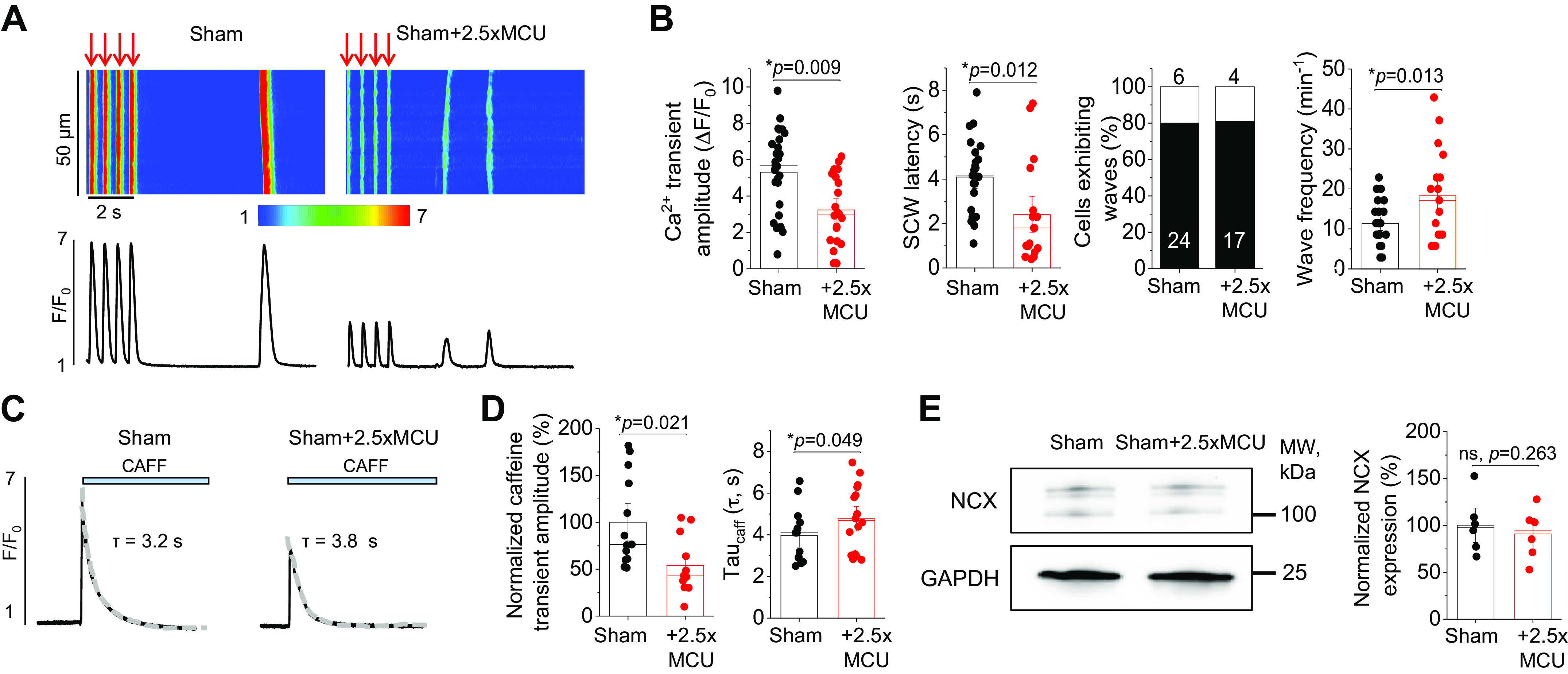

MCU Overexpression in Healthy Myocytes Promotes Proarrhythmic Spontaneous Ca2+ Release

We next sought to assess the effects of MCU overexpression on cytosolic Ca2+ handling (Fig. 3). Cultured sham and sham+MCU VMs were loaded with fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fluo-3 AM and cytosolic Ca2+ transients evoked by a pace-pause protocol (2 Hz, 20 s) were recorded in the presence of ISO (50 nM). The Ca2+ transient amplitude and spontaneous Ca2+ wave (SCW) latency were assessed as an indication of the propensity for proarrhythmic spontaneous SR Ca2+ release (40, 41). As demonstrated in Fig. 3, A and B, sham+MCU VMs had significantly reduced Ca2+ transient amplitude, a reduced SCW latency, and increased wave frequency, all indicative of increased RyR2 activity. Next, SR Ca2+ content was assessed by application of 10 mM caffeine (Fig. 3, C and D). The caffeine transient amplitude was significantly reduced in sham+MCU VMs, indicative of increased SR Ca2+ leak via hyperactive RyR2 channels. The tau of caffeine transient decay was also significantly increased in sham+MCU VMs, indicative of slowed Na+/Ca2+ exchanger type 1 (NCX1)-mediated extrusion of Ca2+ during caffeine exposure. Overexpression of MCU did not change expression of NCX1 in sham VMs (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

MCU overexpression promotes proarrhythmic spontaneous Ca2+ waves and reduces SR Ca2+ content in healthy myocytes. A: confocal line scan images of cytosolic Ca2+ transients and Fluo-3 fluorescence (F/F0) profiles of isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM)-treated sham VMs undergoing 2 Hz pace-pause protocol to induce spontaneous Ca2+ waves (SCWs). A subset of sham VMs was infected with MCU adenovirus (2.5-fold, 2.5×) to enhance mito-[Ca2+]. B: means ± SE of cytosolic Ca2+ transient amplitude at 2 Hz, SCW latency, cells exhibiting waves, and wave frequency. n = 10 sham animals, with VMs from each animal split into sham and sham + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. Cytosolic Ca2+ transient amplitude: n = 28 sham VMs, n = 21 sham + 2.5×MCU VMs. SCW latency: n = 24 sham VMs, n = 17 sham + 2.5×MCU VMs. Wave frequency: n = 24 sham VMs, n = 17 sham + 2.5×MCU VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. C: representative images of caffeine-induced (CAFF, 10 mM) Ca2+ transients in ISO-treated (50 nM) sham and sham + 2.5×MCU VMs. D: means ± SE of caffeine-sensitive SR Ca2+ content and time constant of caffeine transient decay (tau, s). Tau was calculated by fitting fluorescence data to a monoexponential function. n = 10 sham animals, with VMs from each animal split into sham and sham + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. n = 13 sham VMs, n = 12 sham + 2.5×MCU VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. E: Western blot demonstrating NCX1 expression in sham and sham + 2.5×MCU VMs. Data were normalized to GAPDH expression, and are presented as means ± SE. n = 6 sham animals, with VMs from each animal split into sham and sham + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. *P < 0.05, paired Student’s t test. MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter; mito-[Ca2+], mitochondrial calcium concentration; NCX1, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger type 1; ns, not significant; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; VMs, ventricular myocytes.

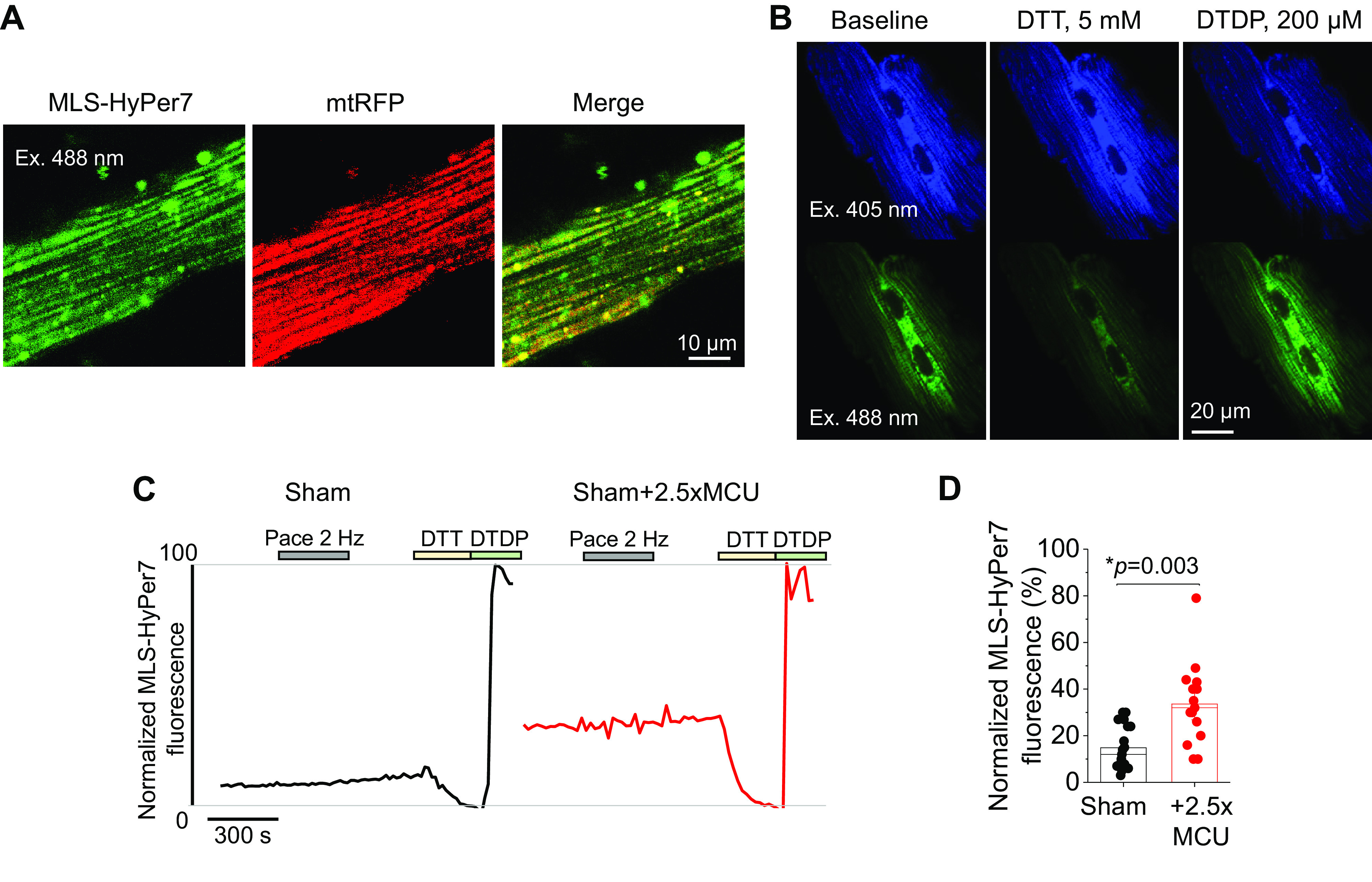

MCU Overexpression in Healthy Myocytes Increases mito-ROS Emission

Increased intracellular ROS and oxidation of RyR2 have been well established to increase the propensity for spontaneous Ca2+ release and proarrhythmic SCWs in cardiac disease. As mitochondria are a major source of ROS (20), we sought to assess whether modulating mito-Ca2+ with MCU overexpression in healthy VMs was driving increased mito-ROS emission. Myocytes were infected with adenovirus encoding the matrix-targeted MLS-HyPer7 H2O2 sensor, and cultured 36–44 h before imaging. Probe sensitivity and correct intracellular localization are demonstrated in Fig. 4, A and B. Indeed, under β-adrenergic stimulation with ISO, sham+MCU VMs have significantly increased MLS-HyPer7 signal versus shams (Fig. 4, C and D).

Figure 4.

MCU overexpression increases mito-ROS emission in healthy myocytes. A: representative confocal images of VM infected with MLS-HyPer7 and mtRFP, with a merged figure to demonstrate correct probe localization. B: representative images of VMs infected with MLS-HyPer7, and treated with DTT (5 mM) followed by DTDP (200 µmol/L) to achieve minimum and maximum fluorescence, demonstrating sensitivity of the ratiometric probe. C: representative traces of MLS-HyPer7 fluorescence from cultured sham VMs. One subset of VMs was infected with MCU adenovirus (2.5-fold, 2.5×) to enhance mito-[Ca2+]. Cells were treated with isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM) for 5 min, before being paced at 2 Hz for a further 5 min. Fluorescence was normalized to minimum (DTT, 5 mM) and maximum (200 µM) fluorescence. D: means ± SE for MLS-HyPer7 fluorescence. n = 7 sham animals, with VMs from each animal split into sham and sham + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. n = 19 sham VMs, n = 15 sham + 2.5×MCU VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. DTDP, deoxythymidine diphosphate; DTT, dithiothreitol; mito-[Ca2+], mitochondrial calcium concentration; MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter; VMs, ventricular myocytes.

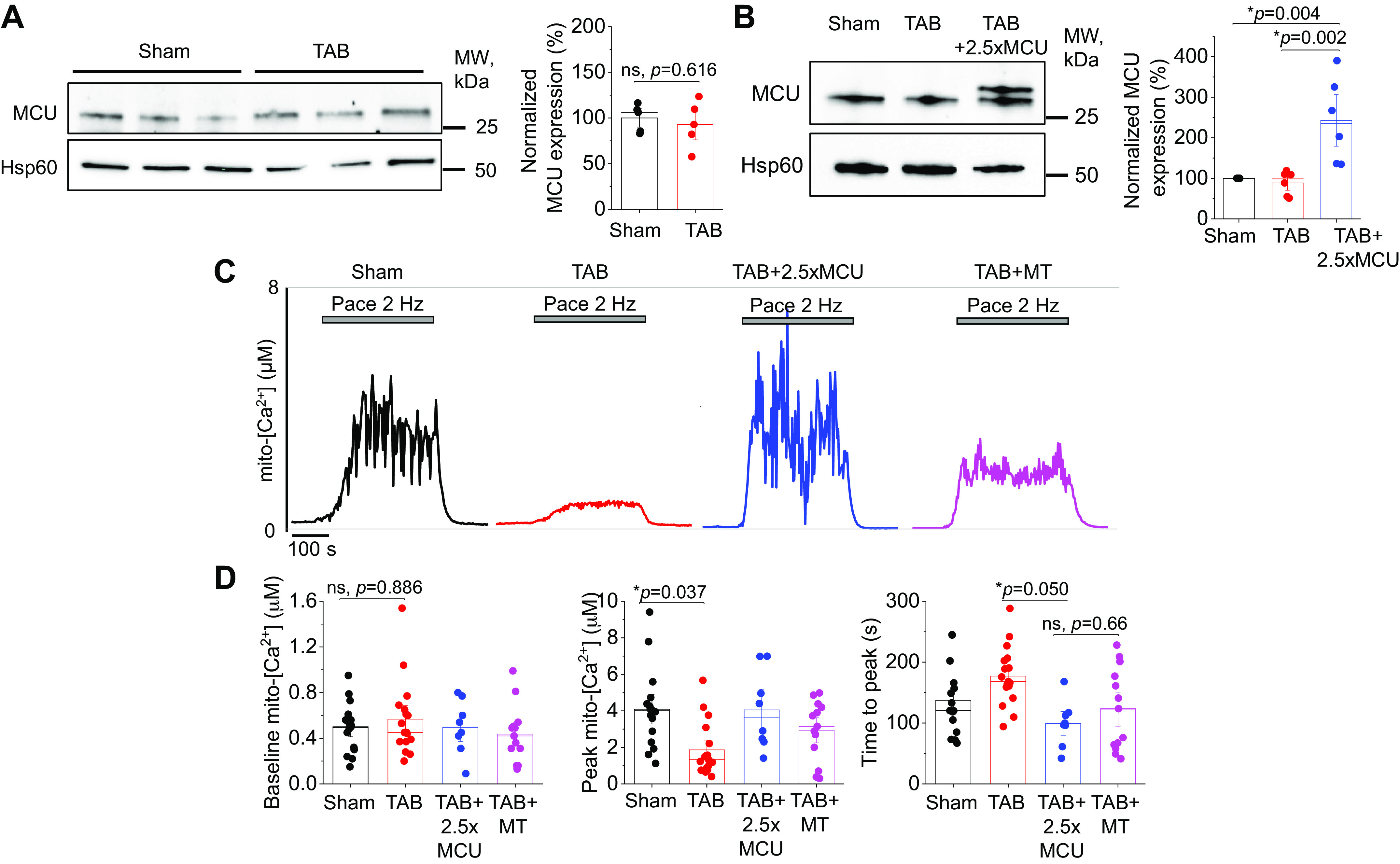

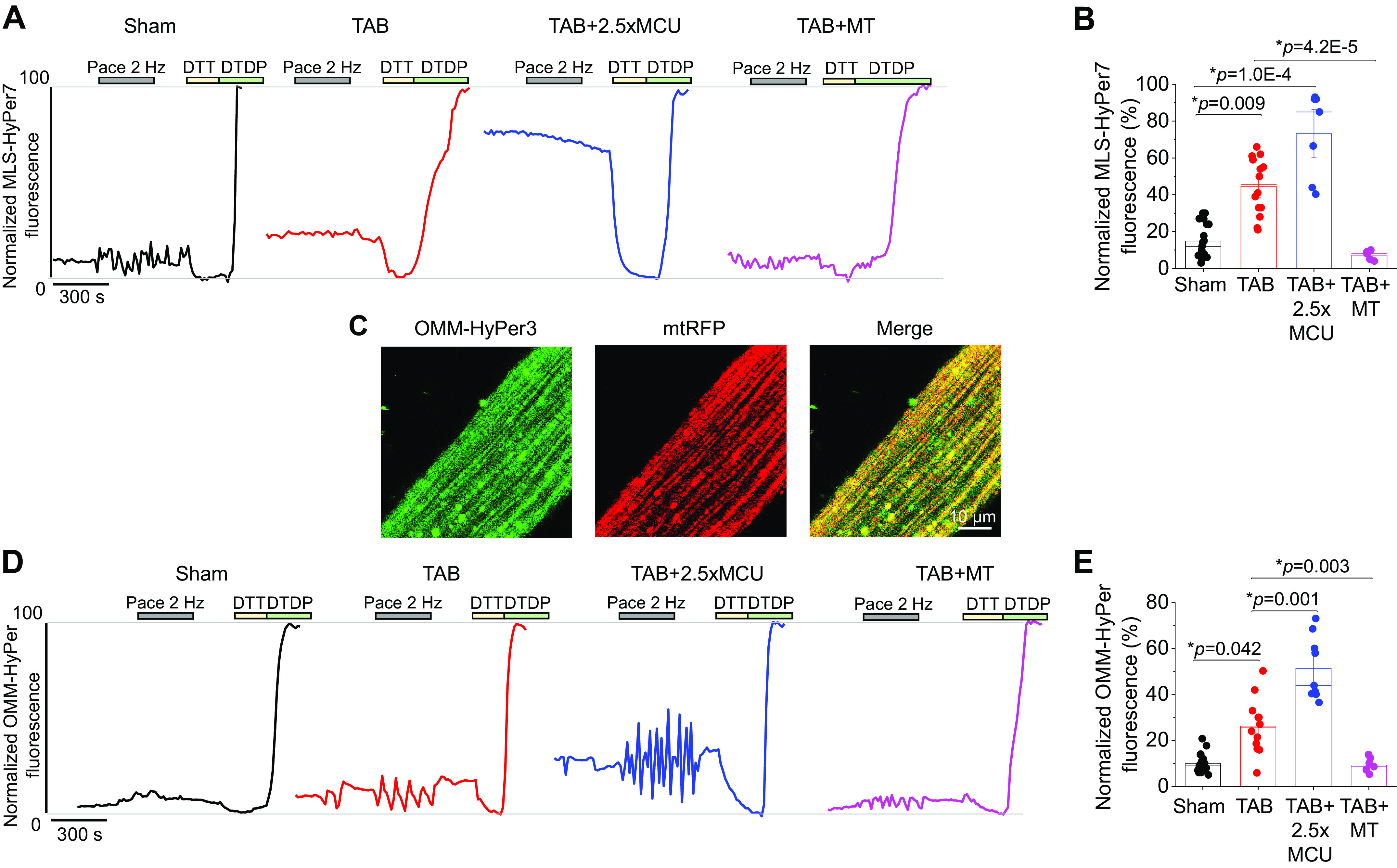

MCU Overexpression Can Restore Mito-[Ca2+] in Hypertrophic Ventricular Myocytes

Although our data demonstrate MCU overexpression is detrimental to intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in healthy myocytes, we also tested this approach in hypertrophic myocytes, given that we and others have previously showed reduced mito-[Ca2+] in diseased VMs (4, 9, 42–44). We first performed Western blot analysis to assess MCU expression of complex proteins in sham and hypertrophic TAB VMs and found no differences (Fig. 5A). We infected TAB VMs with MCU adenovirus, and this increased MCU expression levels of 2.5-fold (Fig. 5B). To assess effects of MCU overexpression on [mito-Ca2+], we used genetic probe mtRCamp1h and followed the recording protocol as described in Fig. 2. Representative traces are shown in Fig. 5C for sham, TAB, TAB+MCU, and TAB+mitoTEMPO-treated (MT, 20 µM, 5-min preincubation) VMs under β-adrenergic stimulation with ISO (50 nM). Quantification reveals that peak mito-[Ca2+] is significantly reduced in TAB versus sham VMs, whereas 2.5-fold MCU overexpression in TAB fully reverses it (Fig. 5D). Pre-treatment with mito-ROS scavenger mitoTEMPO also increased peak-[mito-Ca2+] levels to near sham levels. Both MCU overexpression and treatment with mitoTEMPO modulated mito-Ca2+ flux kinetics, with a reduction in time-to-peak amplitude versus TAB. This demonstrates that 2.5-fold MCU overexpression indeed increases mito-[Ca2+] in TAB VMs to levels similar to shams, and that both MCU overexpression and treatment with mito-ROS scavengers modulates mito-Ca2+ flux.

Figure 5.

2.5-fold MCU overexpression completely restores mito-[Ca2+] in hypertrophic myocytes. A: Western blots demonstrating expression of MCU in cultured sham and TAB rat VMs. Data were normalized to Hsp60 expression, and are presented as means ± SE. B: n = 5 sham, n = 4 TAB animals. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test. B: Western blots demonstrating adenoviral overexpression of MCU (2.5-fold, 2.5×) in cultured TAB VMs. Data were normalized to Hsp60 expression, and are presented as means ± SE. n = 6 sham animals, n = 6 TAB animals, with VMs from each TAB animal split into TAB and TAB + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc adjustment. C: representative traces of cultured sham and TAB VMs expressing Ca2+ biosensor mtRCamp1h. One subset of TAB VMs were infected with MCU adenovirus to enhance mito-[Ca2+], and another was pretreated with mito-ROS scavenger mitoTEMPO (20 µM, 5 min). Myocytes were treated with isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM) for 5 min before pacing at 2 Hz for 5 min. Cells were then saponin permeabilized, treated with EGTA (2 mM) for minimum fluorescence, and Ca2+ (20 µM) to obtain maximum fluorescence. Signal was converted using equation mito-[Ca2+] = 1.3 × (F-min)/(max-F). D: means ± SE of baseline mito-[Ca2+], peak mito-[Ca2+], and time to peak. n = 5 sham animals, n = 5 TAB animals, with VMs from each TAB animal split into TAB, TAB + 2.5×MCU, and TAB+MT groups for culture. n = 16 sham VMs, n = 17 TAB VMs, n = 8 TAB + 2.5×MCU VMs, n = 13 TAB+MT VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter; mito-[Ca2+], mitochondrial calcium concentration; mito-ROS, mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species; ns, not significant; TAB, thoracic aortic banding; VMs, ventricular myocytes.

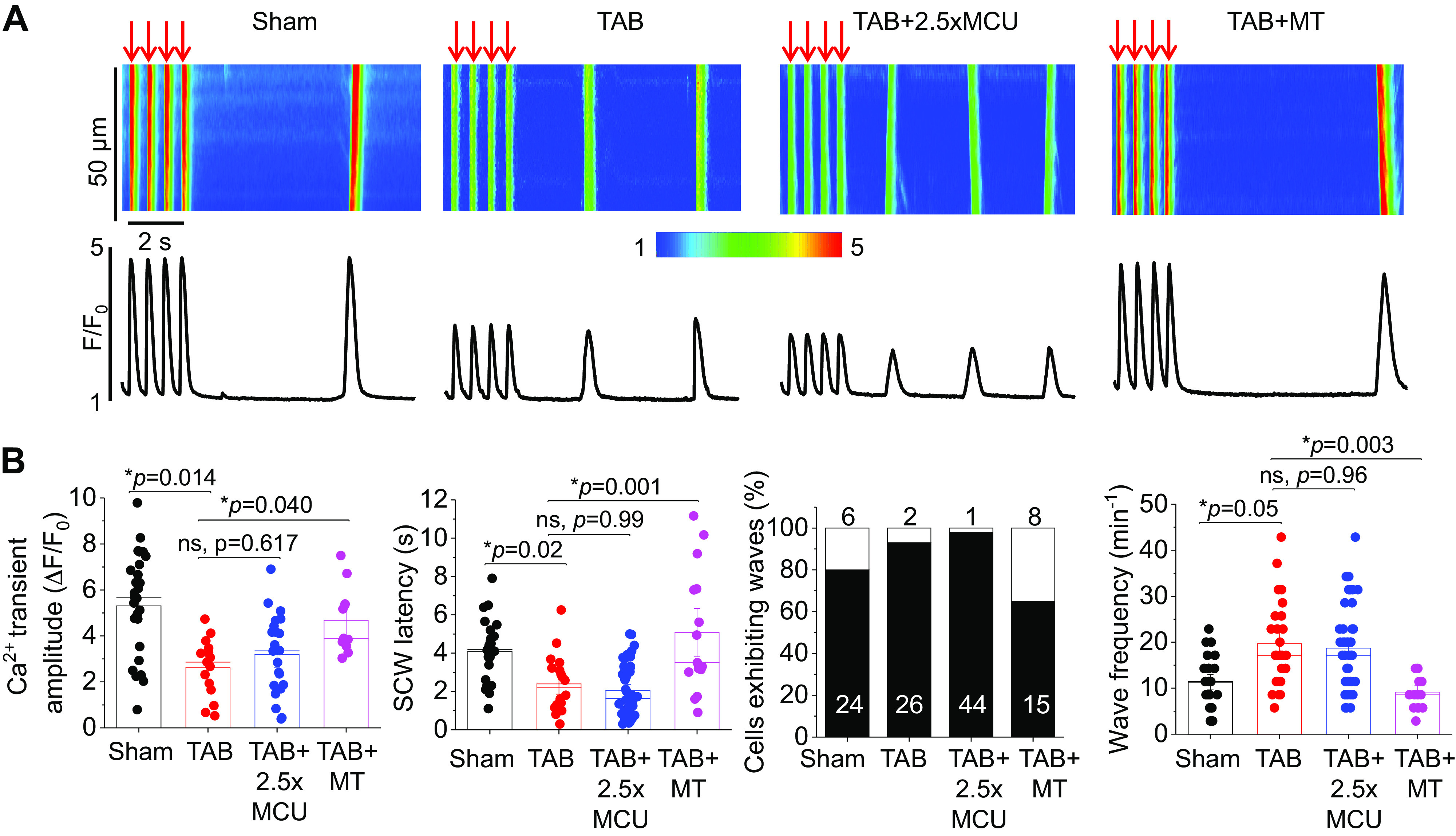

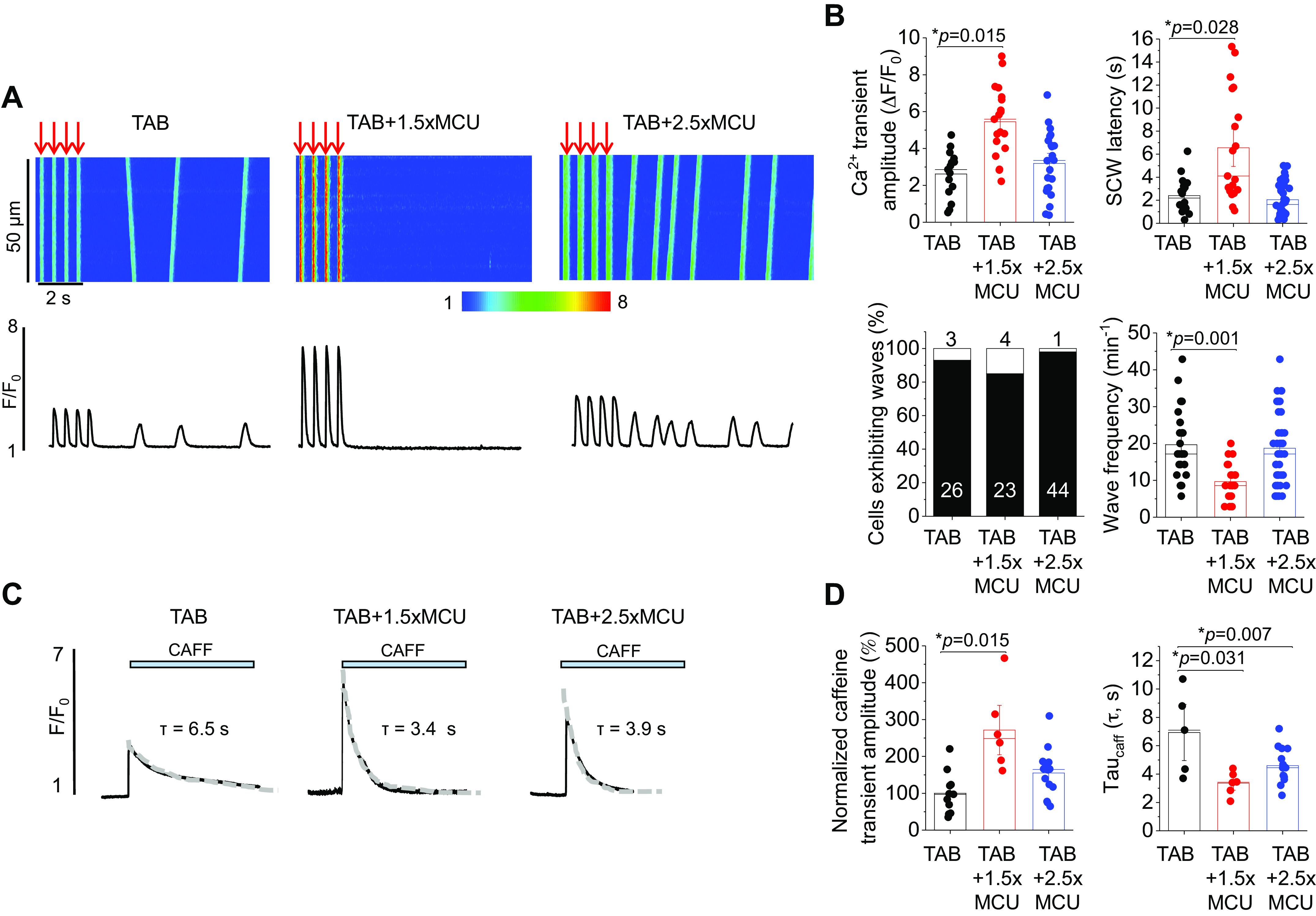

Complete Mito-[Ca2+] Restoration Does Not Attenuate Proarrhythmic RyR2 Activity in Hypertrophic Myocytes

We next assessed the effects of MCU overexpression and mito-ROS scavenging on cytosolic Ca2+ handling. As demonstrated in Fig. 6, A and B, TAB VMs had a significantly reduced Ca2+ transient amplitude, a significantly increased time to half of transient decay and a reduced SCW latency, all indicative of increased RyR2 activity in hypertrophic VMs. Interestingly, 2.5-fold overexpression of MCU did not attenuate any of these parameters in TAB VMs. However, treatment of TAB VMs with mito-ROS scavenger mitoTEMPO increased Ca2+ transient amplitude to sham levels, normalized the time to half of transient decay, and increased SCW latency.

Figure 6.

Complete restoration of mito-[Ca2+] does not restore defective Ca2+ homeostasis in hypertrophic myocytes. A: confocal line scan images of Ca2+ transients and Fluo-3 fluorescence (F/F0) profiles of isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM)-treated sham and TAB rat VMs undergoing 2 Hz pace-pause protocol to induce spontaneous Ca2+ waves (SCWs). One subset of TAB VMs were infected with MCU adenovirus (2.5×) to enhance mito-[Ca2+], and another were pretreated with mito-ROS scavenger mitoTEMPO (MT, 20 µM, 5 min). B: means ± SE of cytosolic Ca2+ transient amplitude at 2 Hz, SCW latency, cells exhibiting waves, and wave frequency. n = 10 sham animals, n = 6 TAB animals, with VMs from each TAB animal split into TAB, TAB + 2.5×MCU, and TAB+MT groups for culture. Cytosolic Ca2+ transient amplitude and SCW latency: n = 28 sham VMs, n = 15 TAB VMs, n = 22 TAB + 2.5×MCU VMs, n = 11 TAB+MT VMs. Wave frequency: n = 24 sham VMs, n = 26 TAB VMs, n = 44 TAB + 2.5×MCU VMs, n = 15 TAB+MT VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter; mito-[Ca2+], mitochondrial calcium concentration; mito-ROS, mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species; TAB, thoracic aortic banding; VMs, ventricular myocytes.

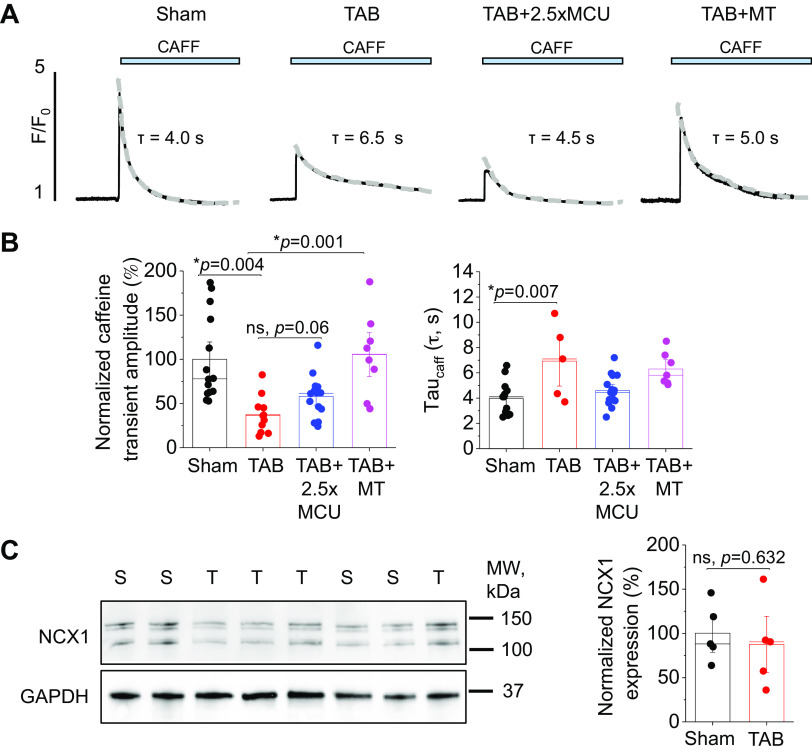

Next, SR Ca2+ content was assessed by application of 10 mM caffeine (Fig. 7, A and B). The caffeine transient amplitude was significantly reduced in TAB VMs, indicative of increased SR Ca2+ leak via hyperactive RyR2 channels. The tau of caffeine transient decay was also significantly increased in TAB VMs, which was reversed by both 2.5-fold MCU overexpression and treatment with mitoTEMPO. However, unlike mitoTEMPO, MCU overexpression did not restore SR Ca2+ content. Western blot analysis showed no change in expression of NCX1 in TAB versus sham VMs (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Complete restoration of mito-[Ca2+] does not restore SR Ca2+ content in hypertrophic myocytes. A: representative images of caffeine-induced (CAFF, 10 mM) Ca2+ transients in isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM)-treated sham and TAB VMs. One subset of TAB VMs were infected with MCU adenovirus (2.5×) to enhance mito-[Ca2+], and another were pretreated with mito-ROS scavenger mitoTEMPO (MT, 20 µM, 5 min). B: means ± SE of caffeine-sensitive SR Ca2+ content and time constant (tau, s) of caffeine transient decay. Tau was calculated by fitting fluorescence data to a monoexponential function. n = 10 sham animals, n = 6 TAB animals, with VMs from each TAB animal split into TAB, TAB + 2.5×MCU, and TAB+MT groups for culture. n = 14 sham VMs, n = 11 TAB VMs, n = 14 TAB + 2.5×MCU VMs, n = 8 TAB+MT VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. C: Western blot demonstrating NCX1 expression in sham and sham + 2.5×MCU VMs. Data were normalized to GAPDH expression, and are presented as means ± SE. n = 5 sham animals, n = 5 TAB animals. *P < 0.05 Student’s t test. MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter; mito-[Ca2+], mitochondrial calcium concentration; NCX1, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger type 1; ns, not significant; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; TAB, thoracic aortic banding; VMs, ventricular myocytes.

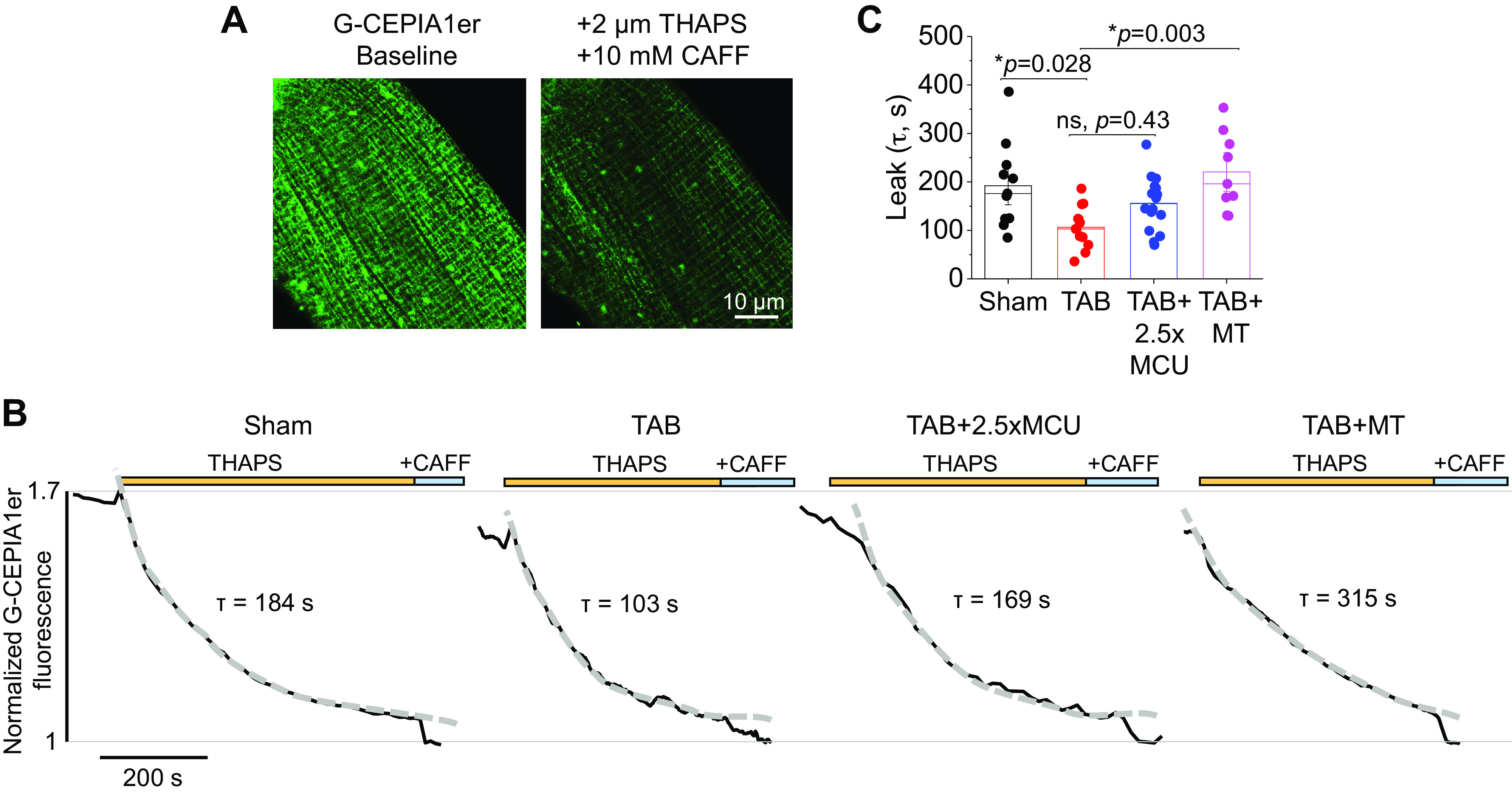

Complete Mito-[Ca2+] Restoration Does Not Reduce RyR2-Mediated SR Ca2+ Leak in Hypertrophic Myocytes

To directly assess RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ leak, we used SR-targeted Ca2+ sensor G-CEPIA1er. Sensitivity of the probe is demonstrated in Fig. 8A. Representative fluorescence recordings are shown in Fig. 8B, where sham and TAB VMs were treated with SERCa2a inhibitor thapsigargin (2 µM) to prevent SR Ca2+ uptake. G-CEPIA1er fluorescence was normalized to minimal fluorescence signal obtained by application of high-dose caffeine (10 mM) to empty the SR at the end of the experiment. The time constant of fluorescence decay (tau) after thapsigargin application was calculated as a measure of RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ leak, by fitting fluorescence data to a monoexponential function (Fig. 8C). Tau of decay was significantly reduced in TAB, indicating increased SR Ca2+ leak rate. Expression of 2.5-fold MCU in TAB VMs did not improve this. Conversely, the increased SR Ca2+ leak rate in TAB was significantly attenuated by treatment of VMs with mitoTEMPO, indicative that increased mito-ROS emission plays a role in increased RyR2 activity.

Figure 8.

Complete mito-[Ca2+] restoration does not reduce RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ leak. A: representative images of VM infected with G-CEPIA1er adenovirus demonstrating probe sensitivity. Myocytes were treated with SERCa2a inhibitor thapsigargin (THAPS, 2 µM) and high-dose caffeine (CAFF, 10 mM) to inhibit SR Ca2+ uptake and deplete the store. B: representative time-dependent profiles (F/F0) of isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM)-treated sham and TAB VMs. One subset of TAB VMs were infected with MCU adenovirus (2.5×) to enhance mito-[Ca2+], and another were pretreated with mito-ROS scavenger mitoTEMPO (MT, 20 µM, 5 min). Myocytes were perfused with ISO for 5 min before recording. Fluorescence was recorded for 30 s before application of THAPS, and the time constant of decay (tau, s) was calculated as a measure of RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ leak, by fitting fluorescence data to a monoexponential function. G-CEPIA1er fluorescence was normalized to minimal fluorescence signal obtained by application of high-dose caffeine to empty the SR at the end of the experiment. C: means ± SE of tau of decay. n = 6 sham animals, n = 7 TAB animals, with VMs from each TAB animal split into TAB, TAB + 2.5×MCU, and TAB+MT groups for culture. n = 11 sham VMs, n = 11 TAB VMs, n = 16 TAB + 2.5×MCU VMs, n = 9 TAB+MT VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter; mito-[Ca2+], mitochondrial calcium concentration; mito-ROS, mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species; ns, not significant; RyR2, ryanodine receptor type 2; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; TAB, thoracic aortic banding; VMs, ventricular myocytes.

Complete Mito-[Ca2+] Restoration Exacerbates mito-ROS Production in Hypertrophic Myocytes

Under β-adrenergic stimulation with ISO, TAB VMs demonstrated significantly increased MLS-HyPer signal versus shams (Fig. 8, A and B). Overexpression of MCU in TAB VMs increased this fluorescence ∼2.5-fold, whereas treatment of VMs with ROS scavenger mitoTEMPO significantly reduced fluorescence to sham levels. In addition, mitoTEMPO treatment was able to attenuate the detrimental effects of 2.5-fold MCU expression in TAB VMs (Supplemental Fig. S1; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.15053040.v1). To ensure that increased levels of ROS in the matrix translated to increased ROS outside of the mitochondria, which could modulate RyR2, we also used the OMM-targeted H2O2 sensor, OMM-HyPer [Fig. 8, C and D, (4)]. Similarly, ROS in this region were increased in TAB versus sham VMs, and MCU overexpression increased levels further. These data suggest that complete restoration of mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ with MCU overexpression does not reduce mito-ROS emission, and exacerbates oxidative stress in hypertrophic VMs.

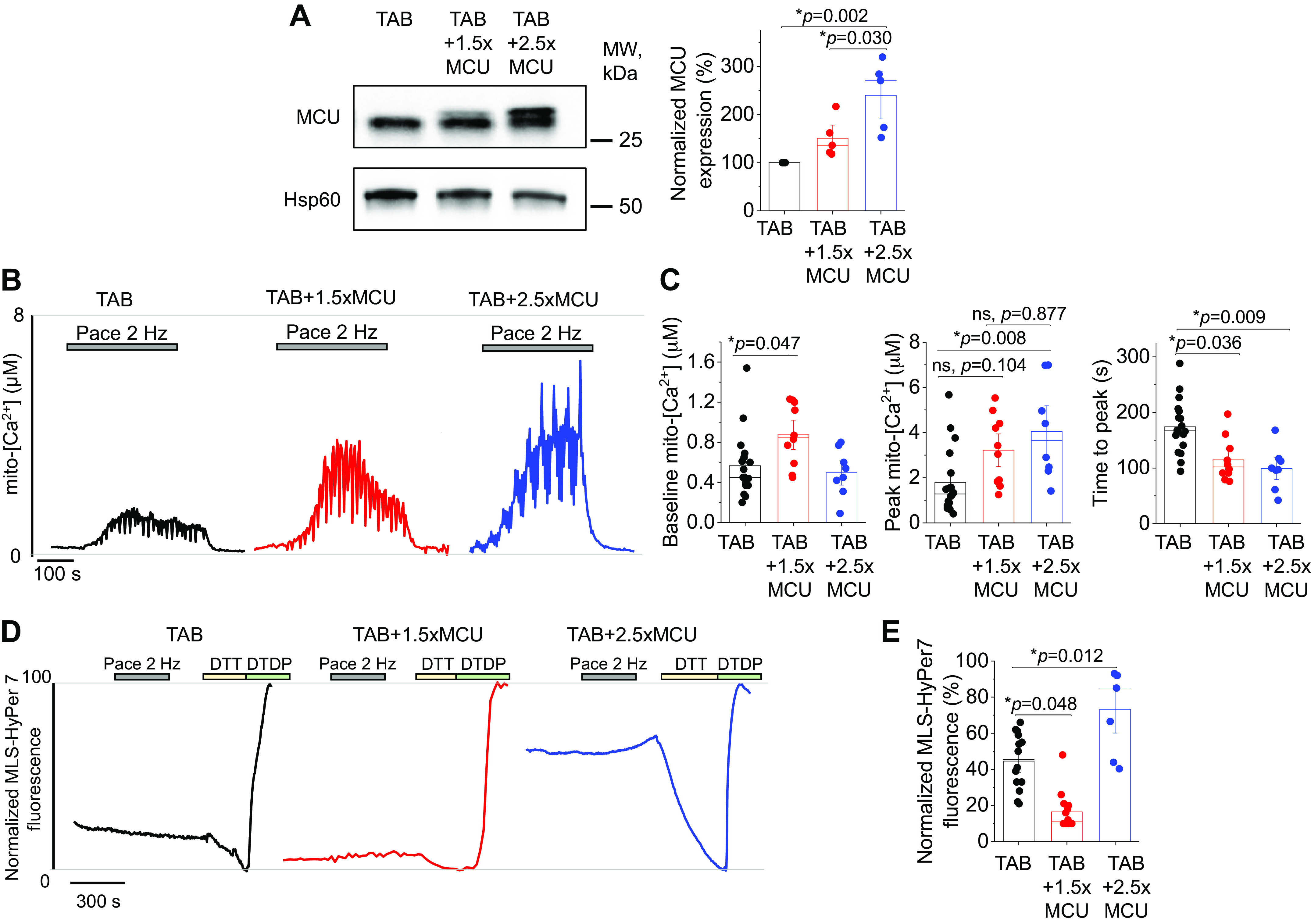

MCU Overexpression at Reduced Levels Can Partially Restore Mito-[Ca2+] and Reduce Mito-ROS Emission in Hypertrophic Myocytes

Although data clearly demonstrate the detrimental effects of overexpressing MCU in both healthy and hypertrophic VMs, it was recently shown that a more modest increase in MCU expression (30%) was beneficial to cardiac function in a guinea pig model of HF, reducing SR Ca2+ leak (10). We therefore sought to make a direct comparison of the effects of modest versus high level overexpression of MCU in hypertrophic TAB VMs. Western blot analysis shown in Fig. 10A demonstrates that we were able to modestly increase MCU expression by 1.5-fold, by reducing adenovirus MOI. Assessment of mito-[Ca2+] with genetic probe mtRCamp1h revealed that 1.5-fold MCU overexpression significantly increased baseline mito-[Ca2+] (Fig. 10, B and C). Although peak [Ca2+] during pacing was not significantly increased in TAB + 1.5MCU versus TAB VMs, there was no statistical difference between peak mito-[Ca2+] of TAB + 1.5MCU versus TAB + 2.5MCU, suggestive there is an intermediate, partial increase in mito-[Ca2+] with modest MCU overexpression (within 2 to 3 µM range), but not to sham levels (4 µM, Fig. 5). Genetic probe MLS-HyPer7 showed that 1.5-fold MCU overexpression in TAB VMs significantly reduced mito-ROS emission.

Figure 10.

Partial restoration of mito-[Ca2+] with 1.5-fold MCU overexpression reduces mito-ROS in hypertrophic myocytes. A: Western blots demonstrating modest (1.5-fold, 1.5×) and high (2.5-fold, 2.5×) adenoviral overexpression of MCU in cultured TAB VMs. Data were normalized to Hsp60 expression, and are presented as means ± SE. n = 5 TAB animals, with VMs from each TAB animal split into TAB, TAB + 1.5×MCU, and TAB + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc adjustment. B: representative traces of cultured TAB VMs expressing Ca2+ biosensor mtRCamp1h. One subset of TAB VMs were infected with 1.5×MCU and another 2.5×MCU. Myocytes were treated with isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM) for 5 min before pacing at 2 Hz for 5 min. Cells were then saponin permeabilized, treated with EGTA (2 mM) for minimum fluorescence, and Ca2+ (20 µM) to obtain maximum fluorescence. Signal was converted using equation mito-[Ca2+] = 1.3 × (F-min)/(max-F). C: means ± SE of baseline mito-[Ca2+], peak mito-[Ca2+], and time to peak. n = 8 TAB animals, with VMs from animals split into TAB, TAB + 1.5×MCU, and TAB + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. n = 17 TAB VMs, n = 10 TAB + 1.5×MCU VMs, n = 8 TAB + 2.5×MCU VMs. *P < 0.05, two level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. D: representative traces of MLS-HyPer7 fluorescence from cultured TAB VMs. Cells were treated with isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM) for 5 min, before being paced at 2 Hz for a further 5 min. Fluorescence was normalized to minimum (DTT, 5 mM) and maximum (200 µM) fluorescence. E: means ± SE for MLS-HyPer7 fluorescence. n = 6 TAB animals, with VMs from each TAB animal split into TAB, TAB + 1.5×MCU, and TAB + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. n = 14 TAB VMs, n = 14 TAB + 1.5×MCU VMs, n = 7 TAB + 2.5×MCU VMs. *P < 0.05, two level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. DTT, dithiothreitol; MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter; mito-[Ca2+], mitochondrial calcium concentration; mito-ROS, mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species; ns, not significant; TAB, thoracic aortic banding; VMs, ventricular myocytes.

Partial Mito-[Ca2+] Restoration Normalizes Cytosolic Ca2+ Handling in Hypertrophic Myocytes

To determine whether partial mito-[Ca2+] restoration and reduced mito-ROS translates to protective effects on intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, we recorded cytosolic Ca2+ transients in TAB VMs with 1.5-fold MCU overexpression (Fig. 11). Indeed, modest MCU overexpression increased Ca2+ transient amplitude, increased SCW latency, and reduced wave frequency compared with TAB VMs with endogenous MCU expression (Fig. 11, A and B). In addition, 1.5-fold MCU overexpression significantly increased caffeine-sensitive SR Ca2+ content, indicative of reduced RyR2 activity (Fig. 11, C and D). Of note, tau of the caffeine-mediated Ca2+ transient was reduced in both TAB VMs expressing 1.5-fold MCU or 2.5-fold MCU.

Figure 11.

Partial restoration of mito-[Ca2+] attenuates defective Ca2+ homeostasis in hypertrophic myocytes. A: confocal line scan images of Ca2+ transients and Fluo-3 fluorescence (F/F0) profiles of isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM)-treated TAB rat VMs undergoing 2 Hz pace-pause protocol to induce spontaneous Ca2+ waves (SCWs). One subset of TAB VMs were infected with 1.5-fold (1.5×) MCU, and another 2.5-fold (2.5×) MCU. B: means ± SE of cytosolic Ca2+ transient amplitude at 2 Hz, SCW latency, cells exhibiting waves, and wave frequency. n = 9 TAB animals, with VMs from each TAB animal split into TAB, TAB + 1.5×MCU, and TAB + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. Cytosolic Ca2+ transient amplitude and SCW latency: n = 15 TAB VMs, n = 19 TAB + 1.5×MCU VMs, n = 22 TAB + 2.5×MCU VMs. Wave frequency: n = 26 TAB VMs, n = 23 TAB + 1.5×MCU VMs, n = 44 TAB + 2.5×MCU VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. C: representative images of caffeine-induced (CAFF, 10 mM) Ca2+ transients in isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM)-treated sham and TAB VMs. One subset of TAB VMs were infected with 1.5-fold (1.5×) MCU, and another 2.5-fold (2.5×) MCU. D: means ± SE of caffeine-sensitive SR Ca2+ content and time constant (tau, s) of caffeine transient decay. Tau was calculated by fitting fluorescence data to a monoexponential function. n = 6 TAB animals, with VMs from each TAB animal split into TAB, TAB + 1.5×MCU, and TAB + 2.5×MCU groups for culture. n = 11 TAB VMs, n = 6 TAB + 1.5×MCU VMs, n = 14 TAB + 2.5×MCU VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter; mito-[Ca2+], mitochondrial calcium concentration; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; TAB, thoracic aortic banding; VMs, ventricular myocytes.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we aimed to test the potential benefit of restoring mito-[Ca2+] to improve intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in hypertrophic VMs from TAB hearts during β-adrenergic stimulation. The main findings are as follows: 1) Adenoviral-mediated 2.5-fold MCU-overexpression in TAB VMs promotes mito-ROS and does not improve defective cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis, despite full restoration of mito-[Ca2+]. 2) Partial restoration of mito-[Ca2+] by 1.5-fold increase in MCU expression levels significantly reduces mito-ROS emission, rescuing Ca2+ handling in TAB VMs. 3) Mito-ROS scavenging in TAB VMs increases SR Ca2+ content and cytosolic Ca2+ transient amplitude, reduces RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ leak, improves refractoriness of SR Ca2+ release and increases mito-[Ca2+].

Adverse Effects of Increased MCU-Mediated Mitochondria Ca2+ Uptake in VMs from Healthy Hearts

Mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ plays a pivotal role in regulating ATP production, primarily as a stimulating influence on Ca2+-dependent dehydrogenases in Krebs cycle that feed electron transport. The MCU complex is established as the major route of Ca2+ entry to the matrix (45, 46). Studies using knockout or loss-of-function MCU experimental models revealed that in cardiac myocytes, the primary role of MCU is to deliver Ca2+ into the matrix during catecholaminergic surge, i.e., conditions mimicking stress, to boost ATP production when metabolic demand is high (7, 47, 48). However, given that the ETC is the major source of ROS, accelerated electron transport during stress may increase mito-ROS to levels that overcome antioxidant defenses and exert detrimental effects on a variety of intracellular signaling systems, including Ca2+-handling machinery. Accordingly, strategies to reduce MCU-mediated Ca2+ influx were proven to have protective effects during ischemia-reperfusion injury or catecholaminergic challenge of hypertrophic hearts, reducing Ca2+-dependent arrhythmia burden by curbing mito-ROS emission (4, 7, 47, 49). On the contrary, acute pharmacological facilitation of MCU-mediated mito-Ca2+ uptake in VMs from healthy hearts exposed to ISO increased mito-ROS and cytosolic Ca2+ mishandling reducing Ca2+ transient amplitude and SR Ca2+ content, while promoting proarrhythmic spontaneous Ca2+ waves (4). Our results confirmed that increased MCU-mediated mito-Ca2+ uptake is detrimental to Ca2+ and ROS homeostasis in ISO-challenged VMs from healthy hearts with MCU overexpression (Figs. 2, 3, and 4). We also show that although basal mito-[Ca2+] in MCU-overexpressing cells is increased, there is no change in maximum mito-[Ca2+] during periodic pacing of ISO-treated VMs. It could be the result of 1) reduced Ca2+ transient amplitude, i.e., less cytosolic Ca2+ available for uptake (16), and 2) depolarization of mitochondria membrane potential and thereby a reduced driving force (4, 16).

There is a continuous debate whether mitochondria can serve as an effective intracellular Ca2+ buffer (4, 6, 50–53). Our results presented here do not support this role. First, if mitochondria were able to significantly interfere with propagation of Ca2+ across the cytosol, one would expect that MCU overexpression would reduce SCWs by intercepting Ca2+ released by RyR2 cluster, before it can ignite the next. Our data show that 2.5-fold MCU overexpression increases SCW frequency instead of decreasing it, which suggest that mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering capability is low (Fig. 6). Although 1.5-fold overexpression increases SCW latency and decreases wave frequency (Fig. 11), this is more likely because reduced mito-ROS emission and therefore RyR2 oxidation and activity, rather than any mito-Ca2+ buffering effect. Furthermore, application of 10 mM caffeine to fully unload the SR showed significant deceleration of caffeine transient decay in both 1.5-fold and 2.5-fold MCU-overexpressing VMs (Figs. 7 and 11), which is opposite to what one would expect if mitochondria plays a significant role in cytosolic Ca2+ removal. Our results are in line with previous studies by the Bers and Lederer groups, demonstrating the dispensable role of mitochondria in cytosolic Ca2+ removal in comparison to NCX1 and SERCa2a (54–57). Given no change in NCX1 expression levels, slowing of the caffeine transient decay is consistent with disturbed intracellular Na+ handling in MCU-overexpressing VMs, secondary to changes in Ca2+ and ROS homeostasis.

Reduced Free Mito-[Ca2+] in Paced Intact Hypertrophic Ventricular Myocytes Under β-Adrenergic Stimulation

The roles of MCU-mediated mito-Ca2+ uptake in cardiac disease remain the subject of ongoing discussion (58). The creation of transgenic mouse models with loss of MCU function revealed that a lack of MCU-mediated Ca2+ uptake does not markedly change mito-[Ca2+] under basal conditions, due to compensatory remodeling (48, 59) and the potential existence of alternative mito-Ca2+-influx pathways. In parallel, these studies confirm its indispensable role in boosting cardiac function during stress as a part of the “fight-or-flight” response (47, 59). To mimic stress, we exposed normal and hypertrophic myocytes to β-adrenergic agonist ISO. Measurements with mtRCamp1h demonstrated reduced mito-[Ca2+] in TAB versus sham VMs undergoing 2-Hz field-stimulation (Fig. 5, C and D). However, this cannot be directly ascribed to reduced activity of the MCU complex, given unchanged MCU expression levels in TAB VMs (Fig. 5). Furthermore, previous studies using isolated mitochondrial samples from diseased or aging hearts consistently showed increased Ca2+ uptake (60, 61). Therefore, the mito-[Ca2+] reduction in intact hypertrophic VMs is most likely secondary to a decrease in Ca2+ transient amplitude (Fig. 6, A and B), i.e., less [Ca2+] available for uptake (16). Another factor could be the acceleration of mito-Ca2+ removal by NCLX, due to a disease-associated increase in intracellular [Na+] (43, 52). Increased intracellular [Na+] contributes to intracellular Ca2+ overload by impeding sarcolemmal NCX1 function. Given no change in NCX1 expression levels in TABs (Fig. 7C), the reduced rate of Ca2+ removal by NCX1 upon 10 mM caffeine application (Fig. 7, A and B) supports that [Na+] is indeed higher in ISO-treated TAB VMs versus shams, which may contribute to matrix mito-Ca2+ unloading.

Complete Mito-[Ca2+] Restoration by 2.5-Fold MCU Overexpression Does Not Rescue Proarrhythmic Ca2+ Handling Remodeling in TABs

Previous works suggested that genetic manipulation of MCU activity may affect function of key elements of intracellular Ca2+ handling machinery. Wu et al. (59) showed that expression of a MCU dominant negative paralog (MCU-DN) increases NCX1 activity, whereas SERCa2a activity may be reduced due to lower levels of ATP production by mitochondria during catecholamine infusion. Our experiments showed that adenovirally mediated 2.5-fold MCU overexpression increases mito-[Ca2+] in TAB VMs under ISO (Fig. 5) rendering them similar to the levels in shams. However, it does not translate into an increase in Ca2+ transient amplitude (Fig. 6) or restoration of SR Ca2+ content (Fig. 7). We previously showed that RyR2s in TAB VMs are hyperactive due to increased oxidation of the channel (4, 39). In line with previous data, we demonstrate enhanced RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ leak (Fig. 8) and shortened latency of proarrhythmic SCWs after cessation of pacing in TAB VMs challenged with ISO (Fig. 6). Our data directly measuring RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ leak provide no evidence of significant reduction in SR Ca2+ leak by 2.5-fold MCU overexpression in TAB VMs (Fig. 8). Importantly, sarcolemmal Na+/K+ ATPase (NKA) is one of the main ATP consumers in cardiomyocytes, as well as SERCa2a and contractile machinery. NKA plays a pivotal role in maintaining intracellular Na+ homeostasis and therefore indirectly affects NCX1 function (62). As seen in Fig. 7, B and C, 2.5-fold MCU overexpression in TABs restores the rate of NCX1-mediated Ca2+ removal during caffeine transient, indicative of Na+ homeostasis restoration. It is consistent with increased NKA function due to increased ATP levels upon overexpression of MCU.

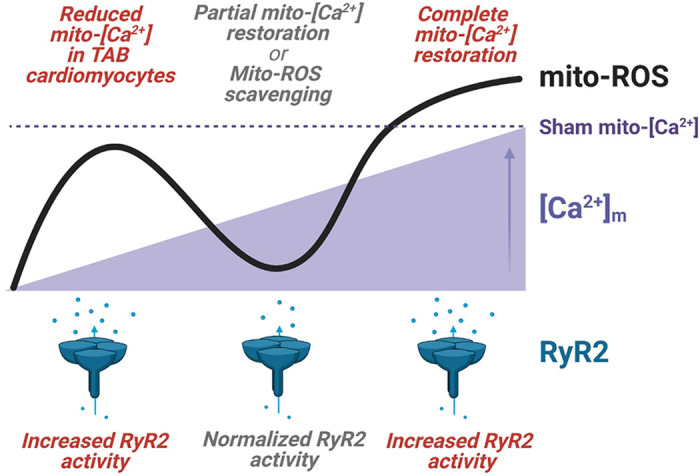

Complete Mito-Ca2+ Restoration by MCU Overexpression Increases Mitochondria ROS Production in TABs, Whereas Partial Restoration Reduces It

In cardiac diseases such as hypertrophy, HF, or DCM, catecholaminergic surge promotes deadly ventricular arrhythmias due to defective RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ release (5, 63). We and others have previously reported that RyR2 oxidative modifications by mito-ROS increase activity of the channel, promoting proarrhythmic spontaneous Ca2+ release in VMs from diseased or aged hearts under β-adrenergic stimulation. Notably, we previously reported that acute pharmacological MCU enhancement with kaempferol has much more profound effects on Ca2+ homeostasis in TAB VMs, decreasing SR Ca2+ content and further exacerbating proarrhythmic spontaneous Ca2+ release (4). We also showed that acute inhibition of MCU-mediated mito-Ca2+ uptake with Ru360 reduces mito-ROS emission, reduces RyR2 oxidation, restores intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, and attenuates Ca2+-dependent ventricular arrhythmias in hypertrophic rat hearts challenged with ISO (4). These beneficial effects are counterintuitive given that mito-[Ca2+] is already reduced in TAB VMs (Fig. 5), which is in line with lowered mito-[Ca2+] levels in VMs from DCM mice or guinea pig HF model (9, 10). Furthermore, pharmacologically or genetically induced restoration of mito-Ca2+ levels by blocking Na+/Ca2+/Li+ exchanger (NCLX) or overexpressing MCU in these two models markedly improved cardiac function. Most recently, Liu et al. (10) reported that moderate adenoviral-mediated MCU overexpression in guinea pig failing hearts reduced ROS in VMs measured with the general H2O2 fluorescent indicator DCFDA. To test effects of MCU overexpression on mitochondrial redox homeostasis in TAB VMs, we expressed mitochondrial matrix-targeted dual-excitation H2O2 sensor MLS-Hyper7 (Fig. 9, A and B). Our results confirmed that the rate of mito-ROS production is increased in hypertrophic cells exposed to ISO. Furthermore, we found that 2.5-fold MCU overexpression drives mito-ROS production even higher. There is a possibility that increased levels of ROS in the matrix do not translate into a surge in ROS outside of mitochondria, which could happen if activities of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase and catalase are increased, for example. To address this possibility, we used an additional H2O2 sensor targeted to mitochondrial outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM). As seen in Fig. 9, D and E, ROS levels in this region are higher in TABs versus shams, and 2.5-fold MCU overexpression elevates it further. Taken together, our results do not support that complete mito-Ca2+ restoration by 2.5-fold MCU overexpression can normalize mitochondrial redox state in diseased VMs under conditions mimicking stress. The question arises how to reconcile our data with reported MCU overexpression-linked decrease in SCD in HF guinea pigs and cardiac function improvement in mice with DCM (9, 10). One potential explanation can come from nonlinearity of mito-Ca2+-mito-ROS relationship, whereby lower than maximal mito-Ca2+ increase can be protective in diseased VMs. Indeed, as seen in Figs. 10 and 11, 1.5-fold MCU overexpression in TAB VMs exposed to ISO that caused partial mito-[Ca2+] recovery significantly reduced mito-ROS emission, and restored cytosolic Ca2+ handling reducing proarrhythmic SCWs. These data, in conjunction with the previously generated body of evidence, suggest a very complex mito-[Ca2+]/mito-ROS relationship, whereby complete MCU block and partial restoration of mito-[Ca2+] content in diseased VMs are protective, whereas both low and high mito-[Ca2+] pathologically increases mito-ROS production (Fig. 12). Our data can help to explain contradictory results from different groups and various models of cardiac disease accompanied with mitochondrial dysfunction and RyR2 hyperactivity (9, 10). It also suggests that the therapeutic window of MCU-mediated mito-Ca2+ uptake enhancement is very narrow, which makes development of treatment strategies exceptionally difficult.

Figure 9.

Complete restoration of mito-[Ca2+] in hypertrophic myocytes increases mito-ROS. A: representative traces of MLS-HyPer7 fluorescence from cultured sham and TAB VMs. One subset of TAB VMs were infected with MCU adenovirus to enhance mito-[Ca2+], and another were pretreated with mito-ROS scavenger mitoTEMPO (20 µM, 5 min). Cells were treated with isoproterenol (ISO, 50 nM) for 5 min, before being paced at 2 Hz for a further 5 min. Fluorescence was normalized to minimum (DTT, 5 mM) and maximum (200 µM) fluorescence. B: means ± SE for MLS-HyPer7 fluorescence. n = 6 sham animals, n = 3 TAB animals, with VMs from each TAB animal split into TAB, TAB + 2.5×MCU, and TAB+MT groups for culture. n = 19 sham VMs, n = 14 TAB VMs, n = 7 TAB+MCU VMs, n = 5 TAB+MT VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. C: representative confocal images of VM infected with OMM-HyPer and mtRFP, with a merged figure to demonstrate correct probe localization. D: representative traces of OMM-HyPer fluorescence from cultured sham and TAB VMs. The same recording protocol was followed as for MLS-HyPer7. E: means ± SE for OMM-HyPer fluorescence. n = 6 sham, 6 TAB animals, n = 19 sham VMs, 12 TAB VMs, 9 TAB+MCU VMs, 7 TAB+MT VMs. *P < 0.05, two-level random intercept model with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment. DTT, dithiothreitol; MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter; mito-[Ca2+], mitochondrial calcium concentration; mito-ROS, mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species; TAB, thoracic aortic banding; VMs, ventricular myocytes.

Figure 12.

The relationship between mito-[Ca2+], mito-ROS and RyR2 activity in hypertrophic myocytes. In TAB VMs under β-adrenergic stimulation, reduced mito-[Ca2+] levels are associated with increased mito-ROS production and increased RyR2 activity. Partial normalization of mito-[Ca2+] with modest MCU overexpression, or scavenging of mito-ROS with mitoTEMPO, can reduce mito-ROS emission and normalizes RyR2 activity. Complete restoration of mito-[Ca2+] with high MCU overexpression to sham levels significantly augments mito-ROS emission and increases proarrhythmic RyR2 activity. Figure created using Biorender.com. MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter; mito-[Ca2+], mitochondrial calcium concentration; mito-ROS, mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species; RyR2, ryanodine receptor type 2; TAB, thoracic aortic banding; VMs, ventricular myocytes.

Mito-ROS Scavenging Improves Both Intracellular and Mitochondrial Ca2+ Homeostasis

Over the last decade, substantial evidence has accumulated to support the promising therapeutic potential of mito-ROS scavenging to rescue defective cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis, improve function of the diseased heart, and reduce the incidence of sudden cardiac death due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias (15, 16, 22, 25, 28, 64). As seen in Fig. 9, preincubation of TAB VMs with mitoTEMPO for 5 min reduces mito-ROS, visualized with mitochondrial-targeted H2O2 biosensors. This leads to restoration of Ca2+ transient amplitude, restoration of SR Ca2+ load, decrease in RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ leak, and significant prolongation of SCW latency in TAB VMs (Figs. 6, 7, and 8); all indicative of RyR2 stabilization. Importantly, stabilization of RyR2 function and mito-ROS reduction with mitoTEMPO were accompanied by a significant improvement in mito-[Ca2+] levels in TAB VMs (Fig. 5). To our knowledge, this is the first direct evidence demonstrating restoration of matrix mito-[Ca2+] in VMs from diseased hearts by mito-ROS scavenging. Interestingly, treatment of TAB VMs with mitoTEMPO results in increased mito-Ca2+ accumulation rate in comparison with TAB VMs. Previous reports suggested that in the presence of oxidative stress, MCU complex activity may be increased. Dong et al. (65) showed that MCU oxidation at Cysteine 97 increases its function. Furthermore, O-Uchi et al. (66) showed that enhanced phosphorylation by Ca2+ and ROS-dependent proline-rich tyrosine kinase Pyk2 promotes MCU subunits multimerization, facilitating mito-Ca2+ uptake. Therefore, it is unlikely that mito-ROS scavenging improves mito-Ca2+ accumulation by reversing posttranslational modifications of MCU in TABs. The more likely scenario is that mito-[Ca2+] increases in paced TAB VMs in the presence of mitoTEMPO, in direct response to Ca2+ transient amplitude restoration (16). Finally, improvement in the decay rate of caffeine transient (Fig. 3) in TAB VMs treated with mitoTEMPO under ISO stimulation is consistent with improvement of Na+ homeostasis possibly via restoration of NKA function, which depends on ATP produced by mitochondria. These data support the high therapeutic potential of improving mito-ROS homeostasis for a broad range of cardiac diseases, including HF, DCM, cardiac hypertrophy, and hereditary arrhythmia syndromes.

Summary

In conclusion, our results suggest that moderate overexpression of MCU can be protective, whereby partial mito-[Ca2+] recovery reduces mito-ROS restoring Ca2+ homeostasis in diseased VMs. On the contrary, complete restoration of mito-[Ca2+] in diseased myocytes by higher MCU overexpression levels produces deleterious effects, amplifying a high rate of mito-ROS production. However, approaches directed at mito-ROS levels normalization appear to have increased therapeutic potential, given substantial improvement in both cytosolic Ca2+ handling and mito-Ca2+ homeostasis in VMs treated with mitoTEMPO.

Limitations

ATP levels were not directly measured in our experiments, given lack of reliable techniques to monitor dynamic changes in ATP concentration in live, periodically paced myocytes. In addition, to overexpress MCU, we used isolated myocytes from hypertrophic hearts maintained in culture for 44 h, instead of in vivo delivery as in Liu et al. (10) and Suarez et al. (9). Culture can lead to structural and electrophysiological remodeling in myocytes, largely after 48 h (33). However, our data with 2.5-fold MCU overexpression in hypertrophic VMs are consistent with our previous report, where using pharmacological MCU enhancement showed exacerbation of Ca2+-dependent arrhythmogenesis in ex vivo whole TAB hearts. In addition, our new findings that partial mito-[Ca2+] restoration can offer protective effects and normalize cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis are in line with work of Liu et al. (10), despite differing models and approaches to increase MCU expression. Also, we used male rats only for this study to allow for a comparison with previous works (10) where only male sex was used, or sex was unreported (9, 12, 52, 55). Sexual dimorphism of mito-Ca2+ handling remains to be explored in future studies.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Fig. S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.15053040.v1.

GRANTS

This work was supported by The Ohio State University President’s Postdoctoral Scholars Award (to S.H.) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01HL135236 (to R.T.C.), R01HL063043 and R01HL074045 (to S.G.), and R01HL142588 and HL121796 (to D.T.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.H. and D.T. conceived and designed research; S.H., R.T., F.P., B.H.O., B.M., M.W.G., and R.T.C. performed experiments; S.H., R.T., M.W.G., A.E.B., and R.T.C. analyzed data; S.H., M.W.G., A.E.B., R.T.C., and D.T. interpreted results of experiments; S.H., R.T., M.W.G., and D.T. prepared figures; S.H. and D.T. drafted manuscript; S.H., B.H.O., M.W.G., A.E.B., R.T.C., S.G., and D.T. edited and revised manuscript; S.H., R.T., F.P., B.H.O., B.M., M.W.G., A.E.B., R.T.C., S.G., and D.T. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown DA, O'Rourke B. Cardiac mitochondria and arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Res 88: 241–249, 2010. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cortassa S, Juhaszova M, Aon MA, Zorov DB, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial Ca2+, redox environment and ROS emission in heart failure: two sides of the same coin? J Mol Cell Cardiol 151: 113–125, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dillmann WH. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 124: 1160–1162, 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamilton S, Terentyeva R, Kim TY, Bronk P, Clements RT, O-Uchi J, Csordás G, Choi BR, Terentyev D. Pharmacological modulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ content regulates sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release via oxidation of the ryanodine receptor by mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species. Front Physiol 9: 1831, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton S, Terentyev D. Proarrhythmic remodeling of calcium homeostasis in cardiac disease; implications for diabetes and obesity. Front Physiol 9: 1517, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton S, Terentyeva R, Clements RT, Belevych AE, Terentyev D. Sarcoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria communication; implications for cardiac arrhythmia. J Mol Cell Cardiol 156: 105–113, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luongo TS, Lambert JP, Yuan A, Zhang X, Gross P, Song J, Shanmughapriya S, Gao E, Jain M, Houser SR, Koch WJ, Cheung JY, Madesh M, Elrod JW. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter matches energetic supply with cardiac workload during stress and modulates permeability transition. Cell Rep 12: 23–34, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu T, Takimoto E, Dimaano VL, DeMazumder D, Kettlewell S, Smith G, Sidor A, Abraham TP, O'Rourke B. Inhibiting mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchange prevents sudden death in a Guinea pig model of heart failure. Circ Res 115: 44–54, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suarez J, Cividini F, Scott BT, Lehmann K, Diaz-Juarez J, Diemer T, Dai A, Suarez JA, Jain M, Dillmann WH. Restoring mitochondrial calcium uniporter expression in diabetic mouse heart improves mitochondrial calcium handling and cardiac function. J Biol Chem 293: 8182–8195, 2018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu T, Yang N, Sidor A, O'Rourke B. MCU overexpression rescues inotropy and reverses heart failure by reducing SR Ca2+ leak. Circ Res 128: 1191–1204, 2021. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.318562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie A, Song Z, Liu H, Zhou A, Shi G, Wang Q, Gu L, Liu M, Xie LH, Qu Z, Sc D Jr.. Mitochondrial Ca2+ influx contributes to arrhythmic risk in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc 7: e007805, 2018. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schweitzer MK, Wilting F, Sedej S, Dreizehnter L, Dupper NJ, Tian Q, Moretti A, My I, Kwon O, Priori SG, Laugwitz KL, Storch U, Lipp P, Breit A, Mederos Y Schnitzler M, Gudermann T, Schredelseker J. Suppression of arrhythmia by enhancing mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in catecholaminergic ventricular tachycardia models. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2: 737–747, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belevych A, Kubalova Z, Terentyev D, Hamlin RL, Carnes CA, Györke S. Enhanced ryanodine receptor-mediated calcium leak determines reduced sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content in chronic canine heart failure. Biophys J 93: 4083–4092, 2007. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.114546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertero E, Maack C. Calcium signaling and reactive oxygen species in mitochondria. Circ Res 122: 1460–1478, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.310082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper LL, Li W, Lu Y, Centracchio J, Terentyeva R, Koren G, Terentyev D. Redox modification of ryanodine receptors by mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species contributes to aberrant Ca2+ handling in ageing rabbit hearts. J Physiol 591: 5895–5911, 2013. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.260521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton S, Terentyeva R, Martin B, Perger F, Li J, Stepanov A, Bonilla IM, Knollmann BC, Radwański PB, Györke S, Belevych AE, Terentyev D. Increased RyR2 activity is exacerbated by calcium leak-induced mitochondrial ROS. Basic Res Cardiol 115: 38, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00395-020-0797-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo M, Guan X, Luczak ED, Lang D, Kutschke W, Gao Z, Yang J, Glynn P, Sossalla S, Swaminathan PD, Weiss RM, Yang B, Rokita AG, Maier LS, Efimov IR, Hund TJ, Anderson ME. Diabetes increases mortality after myocardial infarction by oxidizing CaMKII. J Clin Invest 123: 1262–1274, 2013. [Erratum in J Clin Invest 123: 2333, 2013]doi: 10.1172/JCI65268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terentyev D, Györke I, Belevych AE, Terentyeva R, Sridhar A, Nishijima Y, de Blanco EC, Khanna S, Sen CK, Cardounel AJ, Carnes CA, Györke S. Redox modification of ryanodine receptors contributes to sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in chronic heart failure. Circ Res 103: 1466–1472, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie W, Santulli G, Reiken SR, Yuan Q, Osborne BW, Chen BX, Marks AR. Mitochondrial oxidative stress promotes atrial fibrillation. Sci Rep 5: 11427, 2015. doi: 10.1038/srep11427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zima AV, Blatter LA. Redox regulation of cardiac calcium channels and transporters. Cardiovasc Res 71: 310–321, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin F, Siwik DA, Lancel S, Zhang J, Kuster GM, Luptak I, Wang L, Tong X, Kang YJ, Cohen RA, Colucci WS. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated SERCA cysteine 674 oxidation contributes to impaired cardiac myocyte relaxation in senescent mouse heart. J Am Heart Assoc 2: e000184, 2013. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bovo E, Lipsius SL, Zima AV. Reactive oxygen species contribute to the development of arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves during β-adrenergic receptor stimulation in rabbit cardiomyocytes. J Physiol 590: 3291–3304, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.230748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bovo E, Mazurek SR, Zima AV. Oxidation of ryanodine receptor after ischemia-reperfusion increases propensity of Ca2+ waves during β-adrenergic receptor stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 315: H1032–H1040, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00334.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terentyev D, Rees CM, Li W, Cooper LL, Jindal HK, Peng X, Lu Y, Terentyeva R, Odening KE, Daley J, Bist K, Choi BR, Karma A, Koren G. Hyperphosphorylation of RyRs underlies triggered activity in transgenic rabbit model of LQT2 syndrome. Circ Res 115: 919–928, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joseph LC, Subramanyam P, Radlicz C, Trent CM, Iyer V, Colecraft HM, Morrow JP. Mitochondrial oxidative stress during cardiac lipid overload causes intracellular calcium leak and arrhythmia. Heart Rhythm 13: 1699–1706, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olgar Y, Billur D, Tuncay E, Turan B. MitoTEMPO provides an antiarrhythmic effect in aged-rats through attenuation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Exp Gerontol 136: 110961, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2020.110961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dey S, DeMazumder D, Sidor A, Foster DB, O'Rourke B. Mitochondrial ROS drive sudden cardiac death and chronic proteome remodeling in heart failure. Circ Res 123: 356–371, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mochizuki M, Yano M, Oda T, Tateishi H, Kobayashi S, Yamamoto T, Ikeda Y, Ohkusa T, Ikemoto N, Matsuzaki M. Scavenging free radicals by low-dose carvedilol prevents redox-dependent Ca2+ leak via stabilization of ryanodine receptor in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 49: 1722–1732, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akerboom J, Carreras Calderón N, Tian L, Wabnig S, Prigge M, Tolö J, Gordus A, Orger MB, Severi KE, Macklin JJ, Patel R, Pulver SR, Wardill TJ, Fischer E, Schüler C, Chen TW, Sarkisyan KS, Marvin JS, Bargmann CI, Kim DS, Kügler S, Lagnado L, Hegemann P, Gottschalk A, Schreiter ER, Looger LL. Genetically encoded calcium indicators for multi-color neural activity imaging and combination with optogenetics. Front Mol Neurosci 6: 2, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2013.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bilan DS, Pase L, Joosen L, Gorokhovatsky AY, Ermakova YG, Gadella TW, Grabher C, Schultz C, Lukyanov S, Belousov VV. HyPer-3: a genetically encoded H(2)O(2) probe with improved performance for ratiometric and fluorescence lifetime imaging. ACS Chem Biol 8: 535–542, 2013. doi: 10.1021/cb300625g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pak VV, Ezeriņa D, Lyublinskaya OG, Pedre B, Tyurin-Kuzmin PA, Mishina NM, Thauvin M, Young D, Wahni K, Martínez Gache SA, Demidovich AD, Ermakova YG, Maslova YD, Shokhina AG, Eroglu E, Bilan DS, Bogeski I, Michel T, Vriz S, Messens J, Belousov VV. Ultrasensitive genetically encoded indicator for hydrogen peroxide identifies roles for the oxidant in cell migration and mitochondrial function. Cell Metab 31: 642–653.e6, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki J, Kanemaru K, Ishii K, Ohkura M, Okubo Y, Iino M. Imaging intraorganellar Ca2+ at subcellular resolution using CEPIA. Nat Commun 5: 4153, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banyasz T, Lozinskiy I, Payne CE, Edelmann S, Norton B, Chen B, Chen-Izu Y, Izu LT, Balke CW. Transformation of adult rat cardiac myocytes in primary culture. Exp Physiol 93: 370–382, 2008. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terentyev D, Belevych AE, Terentyeva R, Martin MM, Malana GE, Kuhn DE, Abdellatif M, Feldman DS, Elton TS, Györke S. miR-1 overexpression enhances Ca(2+) release and promotes cardiac arrhythmogenesis by targeting PP2A regulatory subunit B56β and causing CaMKII-dependent hyperphosphorylation of RyR2. Circ Res 104: 514–521, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.181651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sikkel MB, Francis DP, Howard J, Gordon F, Rowlands C, Peters NS, Lyon AR, Harding SE, MacLeod KT. Hierarchical statistical techniques are necessary to draw reliable conclusions from analysis of isolated cardiomyocyte studies. Cardiovasc Res 113: 1743–1752, 2017. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Del Monte F, Butler K, Boecker W, Gwathmey JK, Hajjar RJ. Novel technique of aortic banding followed by gene transfer during hypertrophy and heart failure. Physiol Genomics 9: 49–56, 2002. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00035.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei S, Guo A, Chen B, Kutschke W, Xie YP, Zimmerman K, Weiss RM, Anderson ME, Cheng H, Song LS. T-tubule remodeling during transition from hypertrophy to heart failure. Circ Res 107: 520–531, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamilton S, Polina I, Terentyeva R, Bronk P, Kim TY, Roder K, Clements RT, Koren G, Choi BR, Terentyev D. PKA phosphorylation underlies functional recruitment of sarcolemmal SK2 channels in ventricular myocytes from hypertrophic hearts. J Physiol 598: 2847–2873, 2020. doi: 10.1113/JP277618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim TY, Terentyeva R, Roder KH, Li W, Liu M, Greener I, Hamilton S, Polina I, Murphy KR, Clements RT, Dudley SC Jr, Koren G, Choi BR, Terentyev D. SK channel enhancers attenuate Ca2+-dependent arrhythmia in hypertrophic hearts by regulating mito-ROS-dependent oxidation and activity of RyR. Cardiovasc Res 113: 343–353, 2017. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belevych AE, Terentyev D, Terentyeva R, Ho HT, Gyorke I, Bonilla IM, Carnes CA, Billman GE, Györke S. Shortened Ca2+ signaling refractoriness underlies cellular arrhythmogenesis in a postinfarction model of sudden cardiac death. Circ Res 110: 569–577, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.260455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunello L, Slabaugh JL, Radwanski PB, Ho HT, Belevych AE, Lou Q, Chen H, Napolitano C, Lodola F, Priori SG, Fedorov VV, Volpe P, Fill M, Janssen PM, Györke S. Decreased RyR2 refractoriness determines myocardial synchronization of aberrant Ca2+ release in a genetic model of arrhythmia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 10312–10317, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300052110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dia M, Gomez L, Thibault H, Tessier N, Leon C, Chouabe C, Ducreux S, Gallo-Bona N, Tubbs E, Bendridi N, Chanon S, Leray A, Belmudes L, Couté Y, Kurdi M, Ovize M, Rieusset J, Paillard M. Reduced reticulum-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer is an early and reversible trigger of mitochondrial dysfunctions in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol 115: 74, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00395-020-00835-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kohlhaas M, Liu T, Knopp A, Zeller T, Ong MF, Böhm M, O'Rourke B, Maack C. Elevated cytosolic Na+ increases mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species in failing cardiac myocytes. Circulation 121: 1606–1613, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.914911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu T, O'Rourke B. Enhancing mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in myocytes from failing hearts restores energy supply and demand matching. Circ Res 103: 279–288, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirichok Y, Krapivinsky G, Clapham DE. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature 427: 360–364, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nature02246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Teardo E, Szabò I, Rizzuto R. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 476: 336–340, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]