The International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group (ITMIG) is an academic society that has periodic virtual tumor board meetings to discuss challenging cases. The tumor board consists of an international panel of experts with significant interest and experience in thymic malignancies, with at least one representative from the following specialties; thoracic surgery, medical oncology, radiation oncology, diagnostic radiology, and thoracic pathology. Any clinician anywhere in the world who seeks assistance from the panel is encouraged to participant by submitting a case (including history, clinical questions, and radiographic and histologic images). Following the case discussion, the tumor board summarizes its conclusions in writing for the treating clinician to help guide them in their treatment plan. We present a case discussed at the virtual tumor board meeting conducted in April 2019.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old man with a 25-pack year smoking history was screened for lung cancer with a computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest. The only pertinent family history includes prostate carcinoma of the father and brother. The patient is otherwise healthy.

Imaging

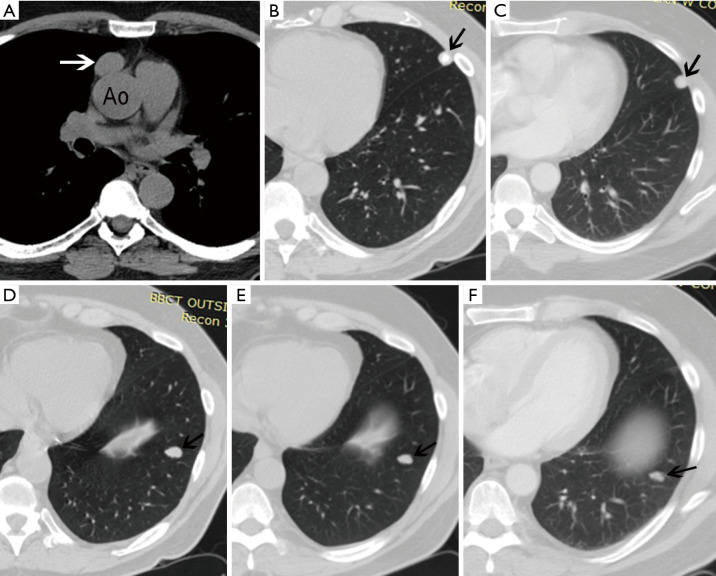

An unenhanced chest CT demonstrates an ovoid 2.7×1.8 cm well-demarcated soft tissue mass in the prevascular mediastinum (Figure 1A), which is new compared to two prior chest CT scans performed 4 and 9 years prior. Even though the mass is near the ascending aorta, there is a fat plane separating it from the aorta, and thus it is confined to the prevascular mediastinal fat with no evidence of pericardial invasion. It is suspicious for a thymoma, staged as T1 by imaging. Although there are no pleural nodules, there are two pulmonary nodules in the left lung. The nodule in the left upper lobe (LUL) is likely benign, since it is heavily calcified (Figure 1B) and has been stable for 9 years (Figure 1C). However, there is a solid non-calcified nodule in the left lower lobe (LLL) that has gradually increased in size to 1.6×1.1 cm over the past 9 years (Figure 1D,E,F). It has an estimated volume doubling time (https://www.radiology.no/vdt/) of 2,200 days (6 years). Although such a long doubling time would suggest the nodule is benign, its contour is lobulated and sometimes low-grade neoplastic nodules, such as carcinoids, may have very long doubling times. It is unusual to see an early T stage thymoma with a solitary pulmonary metastasis in the lung in the absence of pleural metastatic disease. The nodule is amenable to transthoracic needle biopsy because of the size and location, and the ITMIG radiologist would recommend tissue acquisition to establish a histologic diagnosis.

Figure 1.

A 58-year-old man with newly diagnosed prevascular mediastinal mass. Unenhanced chest CT demonstrates a spherical 2.7×1.8 cm ovoid well-demarcated soft tissue mass (arrow in A) in the prevascular mediastinum, abutting the ascending aorta (Ao) but separated from it by a sliver of fat. The pleura is normal, but there are two pulmonary nodules. One is benign as it is heavily calcified (arrow in B) and remained stable compared to a CT performed 9 years earlier (arrow in C). The other nodule, in the left lobe (arrow in D), is lobulated, solid left, and not calcified. It gradually grew over the years currently measuring 1.6×1.1 cm in diameter, whereas in a preceding CT performed 4 years earlier it measured 1.4×0.8 cm in diameter (arrow in E), and 9 years prior to the current CT it measured 1.2×0.7 cm in diameter (arrow in F).

Management

The patient underwent a video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) for right thoracoscopic exploration with mediastinal excision. The operative report indicated the mediastinal mass was approximately 3 cm anterior to the phrenic nerve and the nerve was preserved as the mass was surrounded by mediastinal fat with no invasion of the phrenic nerve or the pericardium. The mass was completely excised. The presenting clinician reported that the post-op chest CT performed 6 weeks later (not available at the time of the ITMIG meeting) demonstrated residual rim of fat in the prevascular space and no change in the LLL nodule.

Pathology

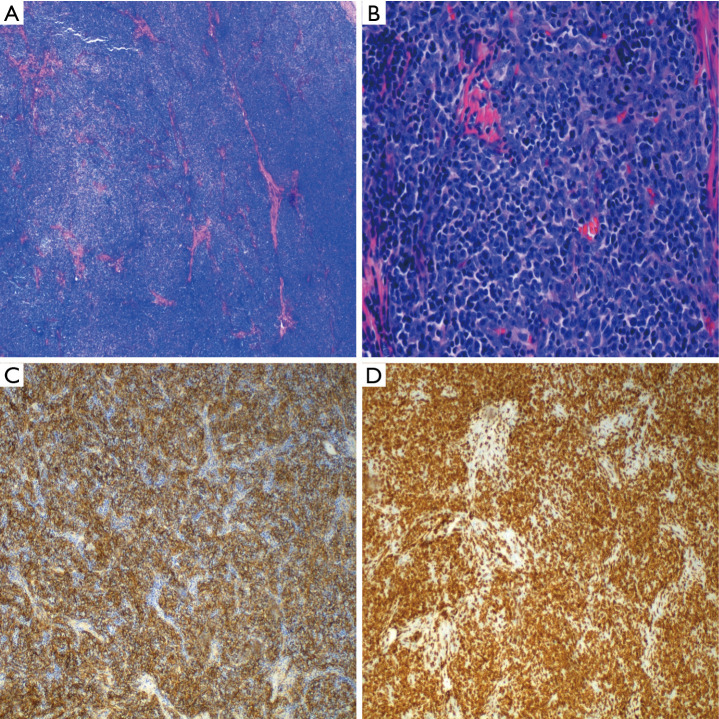

The local pathologist who reviewed the slides after surgery diagnosed a 2.8 cm WHO type AB thymoma with lymphovascular invasion present. Reportedly, the thymoma extended through the capsule into the surrounding adipose tissue. The surgical margins were reportedly positive. The slides provided to ITMIG demonstrated a lobulated neoplasm that is highly cellular with intersecting fibrous bands, a morphology that is suggestive of a thymoma (Figure 2A). However, cytologic details were difficult to evaluate on the provided images due to the quality of the pictures. High magnification images revealed scattered large polygonal cells in a background of small lymphocytes (Figure 2B). Bland appearing spindle cells, as would be expected in type AB thymomas, were not appreciated. Although definite medullary islands were also not noted in the provided images, given the only scattered epithelial cells (large polygonal cells) the morphologic features are suggestive of a WHO type B1 or possibly B2 thymoma; however, maybe the type A component was not depicted. A Cytokeratin stain showed a diffuse meshwork of epithelial cells consistent with type B1 or B2 thymoma (Figure 2C). CD3 highlights background T-lymphocytes, presumably thymocytes (Figure 2D). Furthermore, the provided images do not show the relation between the thymoma and an inked margin (no ink is identified in the provided images) or invasion of the tumor through the capsule into the surrounding adipose tissue.

Figure 2.

(A) A low power view shows a lobulated neoplasm. The hypercellular lobules are focally intersected by fibrous band; (B) at high power, the cellular lobules are comprised predominantly of small lymphocytes. Scattered larger epithelioid cells (neoplastic cells) are also identified; (C) a keratin stain highlights a meshwork of keratin-positive neoplastic cells; (D) the Tdt stain highlights the thymocytes.

Diagnosis

Thymoma, WHO type B1/B2, group stage pI, T1aNXM0 (N0 by imaging) based on focal microscopic invasion into the surrounding mediastinal fat (1,2).

Questions for ITMIG tumor board

The presenting physician asked the ITMIG group whether one should perform a completion thymectomy, and if not whether adjuvant external beam radiotherapy is indicated?

ITMIG expert opinions

The patient had an R1 resection, though it is unclear where the positive margins are. It is unfortunate (but all too frequent) that proper attention was not paid at the time of resection to achieving an R0 resection or marking of areas with a potentially compromised margin. Recent ITMIG data shows that resection of the thymoma alone with a partial thymectomy has comparable outcomes to a complete thymectomy, provided it is an R0 resection. However, in this case it would be difficult to target potential residual thymoma and achieve a reliable R0 resection due to the possible compromised margins not being adequately marked. Thus, there is unclear benefit of further resection and there was consensus that completion thymectomy should not be undertaken.

There are two other issues going forward; adjuvant treatment for the thymoma and the LLL nodule. The recommended next step was to obtain a CT guided biopsy of the slowly enlarging LLL nodule. Of note, thymic epithelial tumors are associated with an increased risk of second cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer, and this possibility must also be ruled out (3,4). This nodule is likely benign as it is rare for a metastasis to appear on imaging prior to the primary, and the LLL nodule was visible in 2009 (prior to the appearance of the thymoma). Additionally, the differences in the rate of growth between the LLL nodule and the mediastinal mass over the past few years suggests that the former is highly unlikely to represent metastatic thymoma. If this nodule is malignant (either an unrelated separate primary or a metastatic thymoma intraparenchymal nodule) it should be completely resected.

The tumor board radiation oncologists recommended adjuvant external beam radiotherapy be offered to the prevascular mediastinal tumor bed of the thymoma if the LLL nodule is found to be benign, or a metastatic thymoma nodule that is completely resected without any pleural metastatic disease. Arguments for post operative radiation therapy (PORT) in this specific case are the unclear margin status, which may be a true positive margin or simply extension to the free margin of the thymus. There is also emerging data on the potential small but measurable survival benefit with PORT for what appears to correspond to a Masaoka-Koga stage IIA thymoma (5). The acute and subacute toxicity of PORT to the prevascular mediastinal tumor bed (e.g., fatigue, lung or esophageal irritation) would be expected to be at an acceptable level. The patient should be counseled on a small but real potential risk of long-term damage to any organs in or near the radiation field, including cardiac sequelae and secondary malignancies.

In the case the nodule proves to be an unrelated separate primary it would influence the prognosis more than the thymoma. In some centres, B2 histology was an indication for PORT, but histology alone is now generally not viewed as an indication to give PORT. However, PORT should be considered for all histologies with incomplete resection (6). The concern about the margin status should be discussed with the patient, though the presenting clinician reported that this is a motivated patient who would prefer further treatment. No radiotherapy to the LLL would be recommended regardless of the pathology.

Chemotherapy is not indicated for this patient with a resected early-stage thymoma (6,7). If the LLL proved to be a solitary thymic metastasis in the left lung this would be considered oligometastatic disease and there is a role for definitive local therapy.

Tumor board members suggested that serial CT imaging with IV contrast every 6 months is indicated for 5 years, then every 2 years and may be continued for 10–15 years (7). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not indicated in this case because minimal changes in nodularity are being assessed for.

Teaching points

❖ Recommend CT guided core needle biopsy of solid non-calcified pulmonary nodule prior to making management decisions for thymoma;

❖ Proper attention should be paid to achieve R0 resection; if not possible areas of potentially compromised margins should be marked.

Post-tumor board

The presenting physician informed ITMIG the attempted CT guided core needle biopsy of the LLL lesion was aborted due to the nodule’s proximity to the diaphragm and spleen, and inability to satisfactorily stabilize the LLL nodule. A wedge resection of the LLL lesion was subsequently completed and pathology demonstrated pulmonary hamartoma (1.3 cm), negative for malignancy. A wedge resection of the LUL lesion was also completed and pathology demonstrated a 1.3 cm hyalinized and calcified nodule and surrounding lung parenchyma with non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the ITMIG members and the colleagues present for the meeting who made the discussion and this publication possible, including the administrative support of P Bruce.

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article and any accompanying images.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/med.2019.11.01). ACR serves as an unpaid Associate Editor of Mediastinum from May 2017 to Apr 2019 and from Jul 2019 to Jun 2021. MM and CBF serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Mediastinum from May 2017 to Apr 2019 and Jul 2019 - Jun 2021. MS serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Mediastinum from Jun 1, 2019 to May 31, 2021. BW serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Mediastinum from Feb 2018 to Jan 2020. EMM reports honorarium for lecture from Bristoll-Meyers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Merck Sharp and Dohme, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Detterbeck FC, Stratton K, Giroux D, et al. The IASLC/ITMIG Thymic Epithelial Tumors Staging Project: proposal for an evidence-based stage classification system for the forthcoming (8th) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumors. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:S65-72. 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detterbeck FC, Nicholson AG, Kondo K, et al. The Masaoka-Koga stage classification for thymic malignancies: Clarification and definition of terms. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:S1710-6. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821e8cff [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamata T, Yoshida S, Wada H, et al. Extrathymic malignancies associated with thymoma: a forty-year experience at a single institution. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2017;24:576-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gadalla SM, Rajan A, Pfeiffer R, et al. A population-based assessment of mortality and morbidity patterns among patients with thymoma. Int J Cancer 2011;128:2688-94. 10.1002/ijc.25583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimner A, Yao X, Huang J, et al. Postoperative radiation therapy is associated with longer overall survival in completely resected stage II and III thymoma: An analysis of the International Thymic Malignancies Interest Group retrospective database. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1785-92. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Detterbeck FC, Parsons AM. Thymic tumors: A review of current diagnosis, classification and treatment. In: Patterson GA, Cooper JD, Deslauriers J, et al. editors. Pearson’s thoracic and esophageal surgery. 3rd edition. Philadelphia, Pa: Churchill Livingstone, 2008:1589-614. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, et al. Thymomas and thymic carcinomas [v2.2019]. In: National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2019. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/thymic.pdf. Accessed May 2019.