Abstract

Background

Zhengqing Fengtongning release tablet (ZQFTN) is a proprietary Chinese medicine preparation of sinomenine, the main active component of the traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) Sinomenium acutum. It is used in China as a complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for knee osteoarthritis (KOA). The objective of this study was to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of ZQFTN in KOA treatment.

Method

Randomized controlled trials of ZQFTN in KOA treatment were searched in PubMed, Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Scientific Journals Database, and Wanfang database. Two reviewers independently conducted the screening, extracted the data, and assessed the methodological quality. Statistical analysis was performed using RevMan 5.3 software.

Results

Eighteen studies were assessed that included 1512 participants (757 in the treatment group and 755 in the control group). The results showed that compared with the control group, the Visual Analogue Scale (standardized mean difference (SMD) = −0.87, 95% confidence interval (CI): [−1.08, −0.66], P < 0.001), Western Ontario and Mc Master University (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index pain score (SMD = −0.67, 95% CI: [−0.88, −0.46], P < 0.001), WOMAC stiffness score (SMD = −0.53, 95% CI: [−0.86, −0.20], P=0.001), WOMAC function score (SMD = −0.76, 95% CI: [−0.97, −0.55], P < 0.001), serum interleukin-1β level (SMD = −4.36, 95% CI: [−6.41, −2.31], P < 0.001), and serum tumor necrosis factor-α level (SMD = −8.45, 95% CI: [−11.20, −5.69], P < 0.001) of the ZQFTN treatment group were lower, and the total effective rate was higher relative risk (RR = 1.15, 95% CI [1.07, 1.23], P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the incidence of adverse reactions between the two groups (RR = 0.96, 95% CI: [0.69, 1.35], P=0.82).

Conclusion

ZQFTN can effectively relieve knee pain, morning stiffness, and daily activity function disorders, reduce the expression of inflammatory factors in serum, and improve the total clinical response rate without increasing the incidence of adverse reactions. Therefore, ZQFTN has considerable potential as a CAM for KOA. However, due to the limitation of the quality of the included studies, the strength of this conclusion is affected. In the next step, multicenter, large sample, high-quality randomized controlled studies are needed to further confirm the present conclusion.

1. Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a degenerative disease that occurs in the knee joint, with chronic joint pain, swelling, stiffness, and dysfunction as the main manifestations. With the increase in life expectancy and aging of the global population, its incidence is increasing and the burden on countries around the world is consequently becoming greater [1]. At present, the drugs used to treat KOA mainly include analgesics, intraarticular corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and symptomatic slow acting drugs for osteoarthritis (SYSADOA) [2–4]. Although these drugs have certain effects on the pain and disease relief of osteoarthritis (OA) patients, they also increase the incidence of gastrointestinal ulcers and cardiovascular events, affecting their use by some patients [5]. Therefore, the need for a safe and effective option for OA treatment has transferred the focus of research from conventional drugs to complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs). Over time, ever increasing evidence has shown that traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) therapies, including acupuncture, galbanum oil, sesame oil, and Qigong, have favorable therapeutic potential as CAMs in OA treatment [6–9].

TCM has a long history, has the advantages of an accurate curative effect, safety and stability, and is a major research topic in the treatment of many difficult diseases [10]. Sinomenine (chemical structure: C19H23NO4, Mw 329.18) is a monomer alkaloid extracted from the TCM Sinomenium acutum, which has anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and immunomodulatory effects [11–14]. It can be used in the treatment of musculoskeletal diseases, neuropathy, cancer, and other diseases [15–19]. At present, Zhengqing Fengtongning release tablets (ZQFTN), sinomenine tablets, and sinomenine hydrochloride injection are used clinically in China [20]. To date, many clinical studies have been reported on the treatment of KOA with ZQFTN [21–38], but there remains a lack of relevant evidence-based medical studies on its efficacy and safety. Because there is no systematic review of oral ZQFTN for KOA treatment, whether ZQFTN can be used as a CAM for clinical KOA treatment remains inconclusive, which complicates the clinician's decision. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis on the efficacy and safety of ZQFTN in KOA treatment using evidence-based medicine for guidance.

2. Materials and Methods

The systematic review protocol was developed with guidance from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021284282).

2.1. Search Strategy

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of ZQFTN in the treatment of KOA were searched in PubMed, Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Scientific Journals Database, and Wanfang database. The retrieval time is from a database construction to August 31, 2021. The retrieval strategy adopted the combination of subject words and free words. The key words were as follows: “Osteoarthritis” “knee osteoarthritis” “KOA” “Zhengqing Fengtongning release tablets” “Zhengqing Fengtongning” “Sinomenine,” and “Sinomenium”. The search strategy was as follows, taking PubMed as an example:

“Osteoarthritis” [Title/Abstract] OR “knee osteoarthritis” [Title/Abstract] OR “KOA” [Title/Abstract]

“Zhengqing Fengtongning release tablets” [Title/Abstract] OR “Zhengqing Fengtongning” [Title/Abstract] OR “Sinomenine” [Title/Abstract] OR “Sinomenium” [Title/Abstract]

“Randomized controlled trial” [Title/Abstract] OR “random trials” [Title/Abstract] OR “Controlled clinical trial” [Title/Abstract]

(1) and (2) and/or (3)

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Study type: RCTs, no language limitation. (2) Participants: patients should be clearly diagnosed with KOA. No restrictions on country, race, age, or gender. (3) Experimental group: in the treatment group, ZQFTN was taken orally alone or combined with other therapies. (4) Control group: any type of control group, including NSAIDs and SYSADOA among others. (5) Outcomes: total effective rate, Visual Analog Scale (VAS), Western Ontario and Mc Master University (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index, serum interleukin-1β (IL-1β) level, serum tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) level, and adverse events.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Repeated publications

Full-text literature is not available

Studies with incomplete data and information

2.3. Literature Screening and Data Extraction

Two reviewers (Zeling Huang and Xiao Mao) searched the literature and screened it independently according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We used standard data extraction methods to extract data. The basic information, sample characteristics, intervention measures, outcome, and other data, which were included in the article, were extracted by two reviewers (Zeling Huang and Xiao Mao). In the case of any inconsistency occurring in the result, this was further discussed by the two researchers or scrutinized by the third reviewer (Zhenqiang Hong).

2.4. Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

A bias risk assessment was conducted by two reviewers (Zeling Huang and Xiao Mao) based on the bias risk assessment tool recommended in the Cochrane manual [39, 40]. The details that were assessed were as follows: (1) random sequence generation; (2) allocation concealment; (3) blinding of participants and personnel; (4) blinding of outcome assessment; (5) incomplete outcome data; (6) selective reporting; and (7) others. Make high risk, low risk, or unclear judgments for each item. Any disagreements were resolved by the third reviewer (Zhenqiang Hong).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Review Manager (RevMan) (Computer program), version 5.3 (the Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014), was used to analyze the collected clinical research data. The enumeration data were evaluated using the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI), and the measurement data were combined using the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. Analysis was performed using a fixed or random effects model according to the heterogeneity. The percentage of heterogeneity in the study was determined by the I2 statistic; if the I2 < 50%, the heterogeneity among the included studies was considered to be small and the fixed effect model was adopted. If I2 ≥ 50%, the heterogeneity among the included studies was considered significant, and the random effect model was adopted [41]. Subgroup analysis was conducted according to different treatments in the treatment group, and sensitivity analysis was also used to analyze the sources of heterogeneity. A value P < 0.10 was considered to suggest statistical heterogeneity and prompted random effects modeling.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search Results

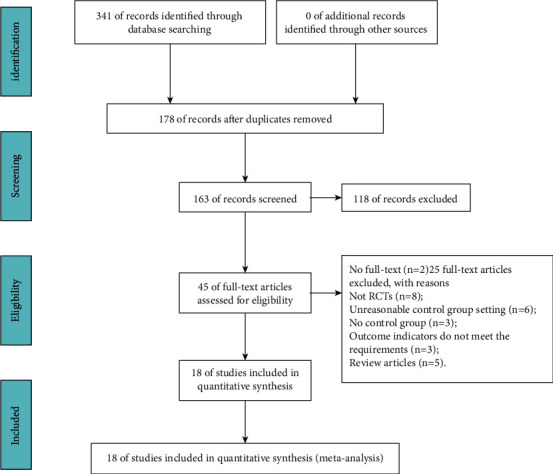

We initially retrieved 341 articles (Figure 1). We subsequently removed 178 duplicate articles manually, leaving 163 articles. Of these 163 articles, 118 were excluded after reading the title and abstract. Of the remaining articles, two lacked full text, and 25 were excluded because they failed to meet the inclusion criteria for complete reading. The present study eventually included 18 articles [21–38].

Figure 1.

Process of searching and screening studies.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

The study of all included papers was a single-center, randomized controlled trial undertaken in China. In total, there were 757 cases in the experimental group and 755 cases in the control group. Except for three studies [28, 31, 33] that did not indicate drug sources, ZQFTN in the other fifteen studies was all produced by Hunan Zhengqing Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. (Huaihua, Hunan, China). The included studies on the ZQFTN dosage are not uniform. Six studies [25, 26, 28, 34, 37, 38] defined ZQFTN alone as the experimental group, with a total of 209 patients, while the control group used SYSADOA, with a total of 209 patients. In seven studies [22, 23, 27, 31–33, 35], ZQFTN combined with SYSADOA was defined as the experimental group, with 318 patients in total, and SYSADOA was used by the control group, with 315 patients in total. In three studies [21, 24, 29], ZQFTN combined with NSAIDs was defined as the experimental group, with a total of 145 patients, and NSAIDs were used by the control group, with a total of 146 patients. In two studies [30, 36], 85 patients were treated with ZQFTN combined with sodium hyaluronate injection as the experimental group, and 85 patients were treated with sodium hyaluronate injection in the control group. The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author, year | Sample size | Sex (male/female) | Age (years) | Treatment | Treatment cycle | Outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG | CG | EG | CG | EG | CG | EG | CG | |||

| Lin ZX, 2008 [21] | 53 | 54 | 15/38 | 16/38 | 63.5 ± 8.7 | 65.7 ± 9.2 | ZQFTN 120 mg bid + CG | Diclofenac sodium sustained-release tablets | 6 months | TER, AE |

| Tang C, 2010 [22] | 33 | 30 | 18/15 | 16/14 | 58.5 ± 8.3 | 59.8 ± 8.1 | ZQFTN 60 mg bid + CG | Glucosamine sulfate capsules | 6 weeks | TER |

| Liu YL, 2011 [23] | 40 | 40 | 19/21 | 22/18 | 63 ± 8 | 62 ± 8 | ZQFTN 60 mg tid + CG | Glucosamine hydrochloride capsules | 3 months | TER, WOMAC, AE |

| Zhao HY, 2011 [24] | 40 | 40 | - | - | 59.975 ± 11.077 | 61.200 ± 10.649 | ZQFTN 120 mg bid + CG | Celecoxib | 8 weeks | TER, AE |

| Xu YX, 2013 [25] | 35 | 35 | 18/17 | 17/18 | 52 | 53 | ZQFTN 60 mg bid | Diacerein capsules | 8 weeks | TER, AE |

| Zhu FX, 2013 [26] | 43 | 43 | 12//31 | 13/30 | 65.17 ± 8.73 | 64.93 ± 9.12 | ZQFTN 60 mg bid | Glucosamine hydrochloride capsules | 12 weeks | TER, WOMAC, IL-1β, TNF-α, AE |

| Zheng CE, 2014 [27] | 40 | 40 | 11//29 | 9/31 | 60.8 ± 6.6 | 61.2 ± 5.8 | ZQFTN 60 mg bid + CG | Glucosamine sulfate capsules | 1 months | TER, AE |

| Liu QY, 2016 [28] | 40 | 40 | 18/22 | 15/25 | 68.15 ± 7.8 | 65.28 ± 1.20 | ZQFTN 60 mg bid | Glucosamine hydrochloride capsules | 10 weeks | TER, WOMAC, IL-1β, TNF-α, AE |

| Wu B, 2017 [29] | 52 | 52 | 36/16 | 34/18 | 62.19 ± 7.20 | 62.24 ± 7.15 | ZQFTN 20 mg tid + CG | Meloxicam | 4 weeks | TER, IL-1β, TNF-α, AE |

| Wang CC, 2017 [30] | 45 | 45 | 16/29 | 18/27 | 49.59 ± 5.70 | 51.63 ± 5.12 | ZQFTN 120 mg bid + CG | Sodium hyaluronate injection | 10 weeks | VAS, TNF-α, AE |

| Luo HC, 2018 [31] | 60 | 60 | 21/39 | 25/35 | 61.28 ± 10.12 | 59.97 ± 11.03 | ZQFTN 60 mg bid + CG | Diacerein capsules | 8 weeks | TER, VAS, WOMAC, AE |

| Luo HC, 2019 [32] | 49 | 49 | 13/36 | 14/35 | 57.49 ± 10.52 | 59.92 ± 10.89 | ZQFTN 60 mg bid + CG | Glucosamine hydrochloride capsules | 12 weeks | TER, IL-1β, TNF-α, AE |

| Mi ZY, 2019 [33] | 50 | 50 | 22/28 | 19/31 | 62.7 ± 5.3 | 60.9 ± 5.0 | ZQFTN 60 mg bid + CG | Diacerein capsules | 2 months | TER |

| Wang GL, 2019 [34] | 30 | 30 | 16/14 | 17/13 | 32.2 ± 8.4 | 40.5 ± 8.2 | ZQFTN 60 mg bid | Diacerein capsules | 8 weeks | TER |

| Zhang Q, 2019 [35] | 46 | 46 | 18/28 | 16/30 | 58.91 ± 5.63 | 58.72 ± 5.81 | ZQFTN 120 mg bid + CG | Diacerein capsules | 8 weeks | TER, VAS, AE |

| Zhang Y, 2019 [36] | 40 | 40 | 22/18 | 21/19 | 52.6 ± 2.5 | 52.7 ± 2.4 | ZQFTN 60 mg bid + CG | Sodium hyaluronate injection | 5 weeks | TER, AE |

| Yang J, 2021 [37] | 20 | 20 | 14//6 | 13//7 | 62.45 ± 4.25 | 62.50 ± 4.00 | ZQFTN 60 mg tid | Glucosamine hydrochloride capsules | 10 weeks | TER, AE |

| Yu Z, 2021 [38] | 41 | 41 | 23/18 | 24/17 | 60.78 ± 8.51 | 61.42 ± 8.23 | ZQFTN 120 mg bid | Diacerein capsules | 3 months | TER, VAS, AE |

EG: experimental group; CG: control group; -: not mentioned; ZQFTN: Zhengqing Fengtongning release tablets; TER: total effective rate; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; WOMAC: Western Ontario and Mc Master University Osteoarthritis Index; IL-1β: serum IL-1β level; TNF-α: serum TNF-α level; AE: adverse events.

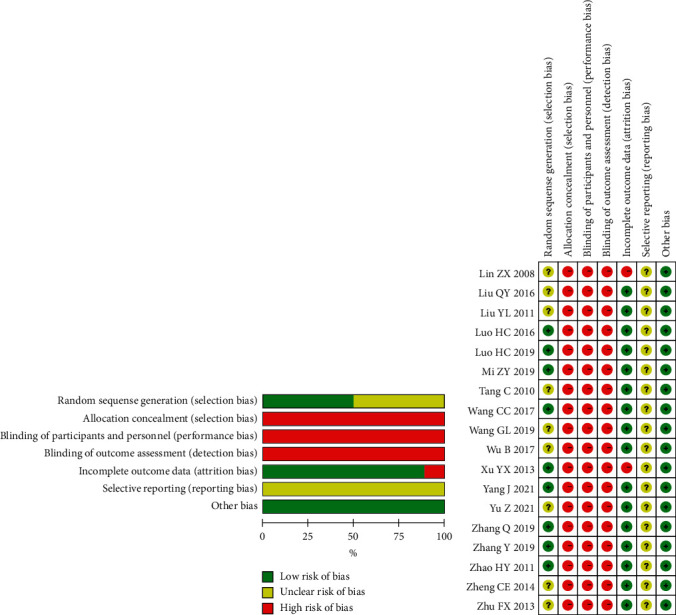

3.3. Methodological Quality of Included Studies

Most of the included studies were of low quality because of unclear randomization, inefficient allocation concealment, inadequate blinding, or described withdrawals and dropouts. Nine studies [24, 25, 30–33, 35–37] were grouped by the random number table method (low risk), and nine studies [21–23, 26–29, 34, 38] did not indicate a specific randomization method (unclear). Eighteen studies [21–38] did not implement allocation hiding (high risk) or blinding (high risk), while sixteen studies [23, 24, 26–38] had complete data (low risk). Because none of the eighteen studies had clinical trial registration in advance, the results of selective reporting were unclear, and none of the eighteen studies found other sources of bias (low risk). The risk of bias assessment is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary and risk of bias graph.

3.4. Treatment Effects

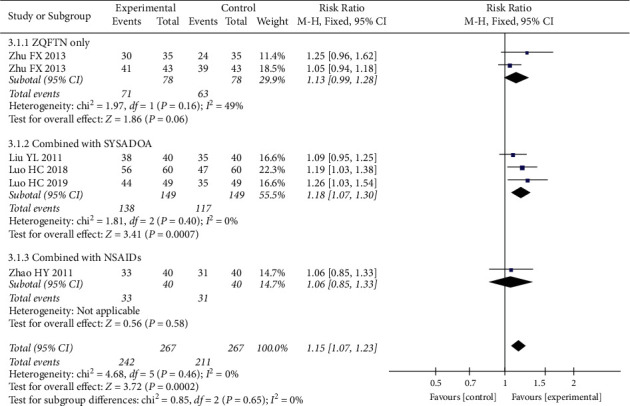

3.4.1. Total Effective Rate

The total effective rate is an important indicator for assessing the effect of treatment, which is mainly based on the changes in the patient's clinical symptoms before and after treatment. A total of seventeen of the included studies reported the total effective rate, but their criteria for judging the treatment effect included the WOMAC score, Lequesne index, and hospital for special surgery knee score. To enhance the strength of the results, we only performed meta-analysis on the six studies that used WOMAC scores to determine the total effective rate, involving a total of 534 patients, with 267 in the experimental group and 267 in the control group. The results of heterogeneity analysis showed good homogeneity among the included studies (P=0.46, I2 = 0%), and the fixed effect model was used for analysis. The results showed that the total effective rate of the experimental group was higher than that of the control group (RR = 1.15, 95% CI: [1.07, 1.23], P < 0.001). The analysis was divided into three subgroups according to different treatment methods of the experimental group. The results of the subgroup analysis showed that the total effective rate of ZQFTN alone was equivalent to that of SYSADOA alone (MD = 1.13, 95% CI: [0.99, 1.28], P=0.06). The total effective rate of ZQFTN combined with SYSADOA was higher than that of SYSADOA alone (RR = 1.18, 95% CI: [1.07, 1.30], P < 0.001). The total effective rate of ZQFTN combined with NSAIDs was equivalent to that of NSAIDs alone (RR = 1.06, 95% CI: [0.85, 1.33], P=0.03) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of total effective rate.

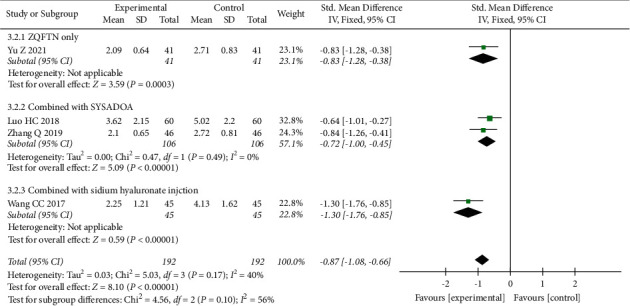

3.4.2. VAS

Four studies [30, 31, 35, 38] reported a pain VAS after treatment, involving a total of 294 patients, 147 in the experimental group, and 147 in the control group. Heterogeneity analysis results showed good homogeneity among the included studies (P=0.17, I2 = 40%), and the fixed effect model was used for analysis. Results showed that the VAS of the experimental group was lower than that of the control group after treatment (SMD = −0.87, 95% CI: [−1.08, −0.66], P < 0.001). The results of subgroup analysis showed that the VAS of ZQFTN alone was lower than that of SYSADOA after treatment (SMD = −0.83, 95% CI: [−1.28, −0.38], P < 0.001). The VAS of the ZQFTN combined with the SYSADOA group was lower than that of SYSADOA alone after treatment (SMD = −0.72, 95% CI: [−1.00, −0.45], P < 0.001). The VAS of ZQFTN combined with sodium hyaluronate injection was lower than that of sodium hyaluronate injection alone after treatment (SMD = −1.30, 95% CI: [−1.76, −0.85], P < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of VAS.

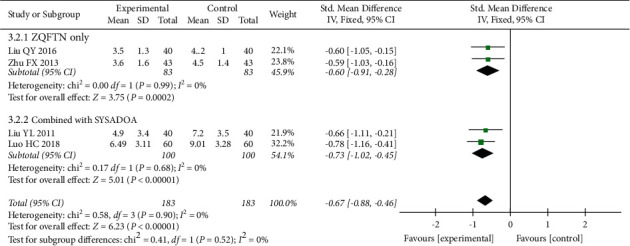

3.4.3. WOMAC Pain Score

Four studies [23, 26, 28, 31] reported the WOMAC pain score after treatment, involving 366 patients (183 in the experimental group and 183 in the control group). Heterogeneity analysis showed good homogeneity among the included studies (P=0.90, I2 = 0%), and the fixed effect model was used for the analysis. The results showed that after treatment, the WOMAC pain score in the experimental group was lower than that in the control group (SMD = −0.67, 95% CI: [−0.88, −0.46], P < 0.001). The results of subgroup analysis showed that the WOMAC pain score of ZQFTN alone was lower than that of SYSADOA after treatment (SMD = −0.60, 95% CI: [−0.91, −0.28], P < 0.001). The WOMAC pain score of ZQFTN combined with SYSADOA was lower than that of SYSADOA alone after treatment (SMD = −0.73, 95% CI: [−1.02, −0.45], P < 0.001) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of WOMAC pain score.

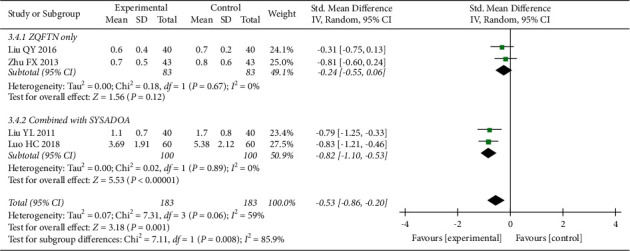

3.4.4. WOMAC Stiffness Score

Four studies [23, 26, 28, 31] reported the WOMAC stiffness score after treatment, involving 366 patients (183 in the experimental group and 183 in the control group). The results of the heterogeneity analysis showed that there was significant heterogeneity among the included studies (P=0.06, I2 = 59%), and the random effect model was used to analyze the results. After treatment, the WOMAC stiffness score in the experimental group was lower than that in the control group (SMD = −0.53, 95% CI: [−0.86, −0.20], P=0.001). Subgroup analysis showed that there was no significant difference in the WOMAC stiffness score between the ZQFTN and SYSADOA groups after treatment (SMD = −0.24, 95% CI: [−0.55, −0.06], P=0.12). The WOMAC stiffness score of ZQFTN combined with SYSADOA was lower than that of SYSADOA alone after treatment (SMD = −0.82, 95% CI: [−1.10, −0.53], P < 0.001) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of WOMAC stiffness score.

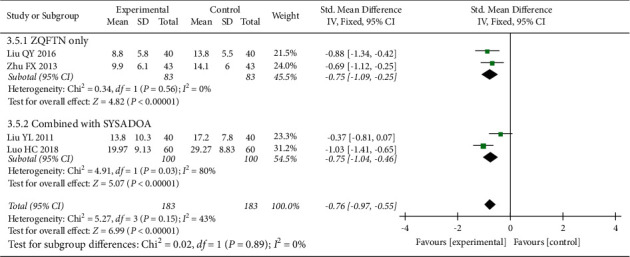

3.4.5. WOMAC Function Score

Four studies [23, 26, 28, 31] reported the WOMAC function score after treatment, involving 366 patients (183 in the experimental group and 183 in the control group). Heterogeneity analysis showed good homogeneity among the included studies (P=0.15, I2 = 43%), and the fixed effect model was used for the analysis. The results showed that after treatment, the WOMAC function score in the experimental group was lower than that in the control group (SMD = −0.76, 95% CI: [−0.97, −0.55], P < 0.001). The results of the subgroup analysis showed that the WOMAC function score of ZQFTN alone was lower than that of SYSADOA after treatment (SMD = −0.78, 95% CI: [−1.09, −0.46], P < 0.001). The WOMAC function score of ZQFTN combined with SYSADOA was lower than that of SYSADOA alone after treatment (SMD = −0.75, 95% CI: [−1.04, −0.46], P < 0.001) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Forest plot of WOMAC function score.

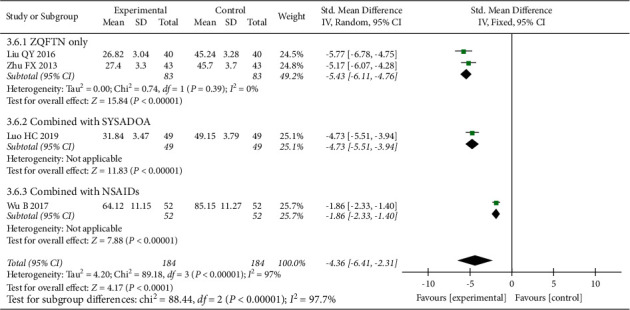

3.5. Serum IL-1β Level

Four studies [15, 16, 24, 28] reported the serum IL-1β level after treatment, involving 368 patients (184 in the experimental group and 184 in the control group). The results of the heterogeneity analysis showed that there was significant heterogeneity among the included studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 97%), and the random effect model was used to analyze the results. The results showed that the serum IL-1β level of the experimental group was lower than that of the control group after treatment (SMD = −4.36, 95% CI: [−6.41, −2.31], P < 0.001). The results of subgroup analysis showed that the serum IL-1β level of ZQFTN alone was lower than that of SYSADOA after treatment (SMD = −5.43, 95% CI: [−6.11, −4.76], P < 0.001). The serum IL-1β level of the ZQFTN combined with SYSADOA group was lower than that of SYSADOA alone after treatment (SMD = −4.73, 95% CI: [−5.51, −3.94], P < 0.001). The serum IL-1β level of ZQFTN combined with NSAIDs was lower than that of NSAIDs alone after treatment (SMD = −1.86, 95% CI: [−2.33, −1.40], P < 0.001) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Forest plot of serum IL-1β level.

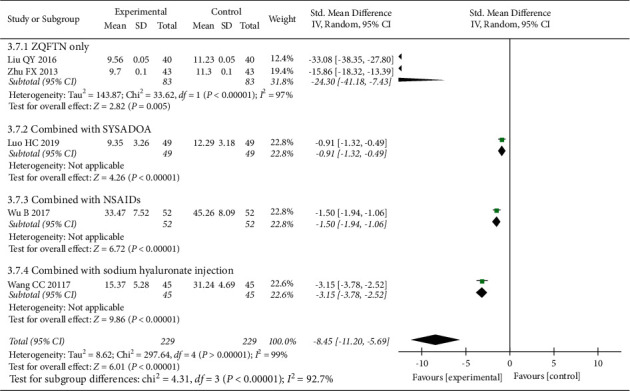

3.6. Serum TNF-α Level

Five studies [15, 16, 24, 28, 30] reported the serum TNF-α level after treatment, involving 458 patients (229 in the experimental group and 229 in the control group). The results of the heterogeneity analysis showed that there was significant heterogeneity among the included studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 99%), and the random effect model was used to analyze the results. The results showed that the serum TNF-α level of the experimental group was lower than that of the control group after treatment (SMD = −8.45, 95% CI: [−11.20, −5.69], P < 0.001). The results of the subgroup analysis showed that the serum TNF-α level of ZQFTN alone was lower than that of SYSADOA after treatment (SMD = −24.30, 95% CI: [−41.18, −7.43], P=0.005). The serum TNF-α level of the ZQFTN combined with SYSADOA group was lower than that of SYSADOA alone after treatment (SMD = −0.91, 95% CI: [−1.32, −0.49], P < 0.001). The serum TNF-α level of ZQFTN combined with NSAIDs was lower than that of NSAIDs alone after treatment (SMD = −1.50, 95% CI: [−1.94, −1.06], P < 0.001). The serum TNF-α level of ZQFTN combined with sodium hyaluronate injection was lower than that of sodium hyaluronate injection alone after treatment (SMD = −3.15, 95% CI: [−3.78, −2.52], P < 0.001) (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Forest plot of serum TNF-α level.

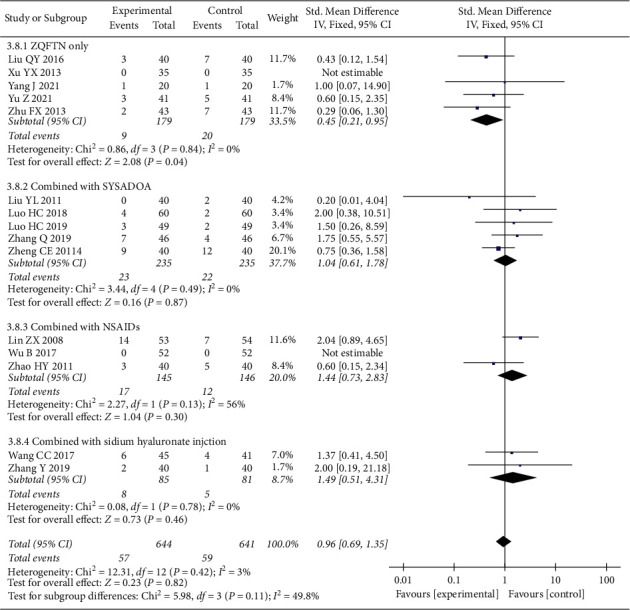

3.7. Adverse Events

Fifteen studies [21, 23–32, 35–38] reported the adverse events after treatment, involving 1285 patients (644 in the experimental group and 641 in the control group). Heterogeneity analysis showed good homogeneity among the included studies (P=0.42, I2 = 3%), and the fixed effect model was used for the analysis. The results showed that there was no significant difference between the experimental group and the control group (RR = 0.96, 95% CI: [0.69, 1.35], P=0.82). The results of the subgroup analysis showed that ZQFTN alone had less adverse events than SYSADOA alone (RR = 0.45, 95% CI: [0.21, 0.95], P=0.04). There was no significant difference between the ZQFTN combined with SYSADOA group and the SYSADOA group (RR = 1.04, 95% CI: [0.61, 1.78], P=0.87). There was no significant difference in adverse events between ZQFTN combined with NSAIDs and NSAIDs alone (SMD = 1.44, 95% CI: [0.73, 2.83], P=0.30). There was no significant difference in adverse events between ZQFTN combined with sodium hyaluronate injection and sodium hyaluronate injection alone (RR = 1.49, 95% CI: [0.51, 4.31], P=0.46) (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Forest plot of adverse events.

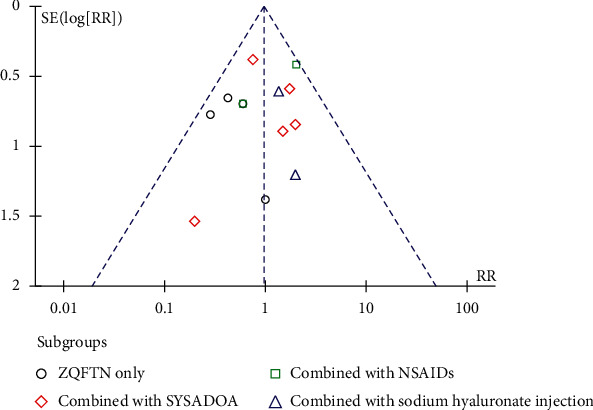

3.8. Publication Bias

The inverted funnel plot of publication bias was generated with the adverse reactions as indicators, and the scatter point distribution of each study was asymmetric, suggesting the possibility of publication bias in this study (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Publication bias of the funnel plot of adverse events.

4. Discussion

Sinomenium acutum is the vine stem of the Asteraceae plant and Chinese Anseraceae plant among others. It is a TCM, which has the function of dispelling wind dampness, channelling channels and collaterals, and relieving urination, and is often used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, OA, and gout arthritis [42]. Sinomenine is an alkaloid extracted from Sinomenium acutum and is the main active ingredient of Sinomenium acutum. Experimental studies have found that sinomenine has clear anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects. Its anti-inflammatory effect mainly results from its selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 activity, whereby capillary permeability is reduced by downregulating prostaglandin E synthesis, or preventing histamine-induced capillary permeability increase by inhibiting the release of various inflammatory mediators, thus blocking inflammatory infiltration and exudation. Sinomenine also has anticoagulation and antiembolism effects and reduces tissue damage [20]. Studies have shown that sinomenine can reduce synovial inflammation and cartilage degeneration by inhibiting the expression of inflammatory factors and chondrocyte apoptosis, thus delaying the progression of osteoarthritis [43]. ZQFTN as an oral preparation of sinomenine has been used ever more frequently in the clinical treatment of OA.

4.1. Effectiveness of ZQFTN in Treating KOA

Through a literature search, it was found that ZQFTN could be used as a complementary drug in combination with SYSADOA, NSAIDs, or sodium hyaluronate, or used alone as an alternative drug for KOA. The results showed that ZQFTN has good efficacy, but due to the influence of inconsistent treatment methods, insufficient sample size, and other factors, the conclusions were frequently unconvincing and the evidence basis was not strong. To determine the effectiveness of oral ZQFTN in KOA treatment, 18 RCTs were included in the present study, including 1512 KOA patients. The results of the meta-analysis showed that ZQFTN could effectively relieve knee pain, morning stiffness, and daily activity disturbance. The VAS and WOMAC scores were lower than the control group, and the total clinical effectiveness rate was higher than the control group, indicating that ZQFTN had significant clinical efficacy as a CAM for KOA. The results of serum IL-1β and TNF-α showed that their respective levels in the experimental group were lower than those in the control group, suggesting that the mechanism of ZQFTN in treating KOA may be associated with its ability to reduce inflammation.

4.2. Safety of ZQFTN in Treating KOA

Adverse events related to drug treatment were recorded in 15 studies, and meta-analysis results showed that there was no significant difference in the incidence of adverse reactions between the experimental and control groups. The reported adverse reactions were mainly gastrointestinal, including nausea and diarrhea, and allergic reactions, such as pruritus and rash, which were consistent with the adverse events recorded in the instructions of ZQFTN, SYSADOA, and NSAIDs. Eight studies monitored the changes of blood routine and liver and kidney functions during medication, including 737 KOA patients. The results showed that a total of five patients in the experimental groups displayed a slight increase in transaminases, while a further seven patients in control groups showed a slight increase in transaminases, which returned to normal after symptomatic treatment. These results indicated that the use of ZQFTN did not increase the risk for adverse events and that it was safe as a CAM for KOA.

4.3. Limitations of the Study

Through a comprehensive analysis of the included literature, the following problems were found to generally exist in this literature: (1) There was no allocation concealment or blind method in all studies, and strict and careful experimental design was lacking. (2) The sample size of some of the literature was small, and the calculation basis of sample size was not given. (3) There were differences in medication duration and dosage in the included studies, which were not conducive to the formation of standardized medication guidance. (4) Because there is no standardized ZQFTN in other countries, all analyzed studies were performed in China, which may have led to a certain bias.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrated that ZQFTN has high clinical efficacy and safety in the treatment of KOA and thus has considerable potential as a CAM for KOA. However, due to the limitation of the quality of included studies, the strength of this conclusion is affected. In the next step, multicenter, large sample, high-quality randomized controlled studies are needed to further confirm the present conclusion.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank International Science Editing (http://www.internationalscienceediting.com) for editing this manuscript.

Data Availability

The table data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article. The figure data used to support the findings of this study are included within the figure files.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this study.

Authors' Contributions

HZL, MX, and CJM contributed equally to this work. HZL and HZQ contributed to the conception and design of the review. HZL and MX performed the search strategy. HZL and MX developed the search criteria and performed data extraction quality evaluation. HZL and CJM analyzed the data. HZL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. HJJ, SSN, GM and GHJ critically edited the manuscript. HZL and HZQ were responsible for the overall project. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Safiri S., Kolahi A. A., Smith E. Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990-2017: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases . 2017;79(6):819–828. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz J. N., Arant K. R., Loeser R. F. Diagnosis and treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis. JAMA . 2021;325(6):568–578. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Persson M. S. M., Stocks J., Varadi G., et al. Predicting response to topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in osteoarthritis: an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatology . 2020;59(9):2207–2216. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magni A., Agostoni P., Bonezzi C., et al. Management of osteoarthritis: expert opinion on NSAIDs. Pain and Therapy . 2021;10(2):783–808. doi: 10.1007/s40122-021-00260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelletier M., Barr A. J., Cicuttini F. M. Osteoarthritis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers . 2017;2 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.72.16072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tu J. F., Yang J. W., Shi G. X., et al. Efficacy of intensive acupuncture versus sham acupuncture in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis & Rheumatology . 2021;73(3):448–458. doi: 10.1002/art.41584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emami Razavi Z., Karimi M., Khamessi M. Effects of galbanum oil on patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Traditional and Integrative Medicine . 2016;1(3):101–107. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Askari A., Ravansalar S. A., Naghizadeh M. M. The efficacy of topical sesame oil in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized double-blinded active-controlled non-inferiority clinical trial. Complementary therapies in medicine . 2019;47 doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.08.017.102183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung K. C. W. Mind-body health benefits of traditional chinese qigong on women: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/7443498.7443498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L., Zhang X. F., Zhang X. Evaluation of the therapeutic effect of traditional Chinese medicine on osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Research and Management . 2020;10 doi: 10.1155/2020/5712187.5712187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamasaki H. Pharmacology of sinomenine, an anti-rheumatic alkaloid from sinomenium. 1976;30(1):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang W., Fan W., Gao T. Analgesic Mechanism of Sinomenine against Chronic Pain. Pain Res Manag . 2020;5 doi: 10.1155/2020/1876862.1876862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou H., Liu J.-X., Luo J.-F., et al. Suppressing mPGES-1 expression by sinomenine ameliorates inflammation and arthritis. Biochemical Pharmacology . 2017;142(10):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao T., Hao J., Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z., Wang D. Q., Xu X. J. Analgesic effect of sinomenine in rodents after inflammation and nerve injury. European Journal of Pharmacology . 2013;721(1-3):5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang R. Y., Pan H. d., Wu J.-q., et al. Comparison of combination therapy with methotrexate and sinomenine or leflunomide for active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine . 2019;57:403–410. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao Z., Lin Y., Zhang P., et al. Sinomenine ameliorates intervertebral disc degeneration via inhibition of apoptosis and autophagy in vitro and in vivo. American Journal of Tourism Research . 2019;11(9):5956–5966. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X., Liu Y., Zhang H. Sinomenine alleviates dorsal root ganglia inflammation to inhibit neuropathic pain via the p38 MAPK/CREB signalling pathway. European Journal of Pharmacology . 2021;897 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173945.173945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song L., Zhang H., Hu M. Sinomenine inhibits hypoxia induced breast cancer side population cells metastasis by PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry . 2020;13 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115986.115986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu F., Li Q., Wang Z., Cao X. Sinomenine inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion and promotes apoptosis of prostate cancer cells by regulation of miR-23a. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie . 2019;112 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.01.053.108592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X., Zhang Z. Y., Chou P. Research progress of Sinomenium acutum and Sinomenine and their related preparations. Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal . 2021;56(2):85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin Z. X., Cui Z. J., Dai Y. C. Clinical observation on 58 cases of knee osteoarthritis treated with Zhengqing Fengtongning combined with Western medicine. Guiding Journal of TCM and Pharmacy . 2008;8:49–51. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang C., Cai X. Y., Lin X. J. Clinical observation of glucosamine combined with Zhengqing Fengtongning release tablets in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. China Modern Doctor . 2010;48(23):29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y. L., Liu Y. M., Liu Y. X. Clinical observation of Zhengqing Fengtongning combined with Puli in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Hebei Medical Journal . 2011;33(7):1082–1083. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao H. Y., Huang Y. Z., Zhang J. 40 cases of knee osteoarthritis treated by Zhengqing Fengtongning combined with celecoxib. Herald of Medicine . 2011;30(7):907–910. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xv Y. X. Clinical Study of Zhengqing Fengtongning Release Tablets in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee . Changsha, China: Hunan University of TCM; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu F. X., Zhou R. H., Shi Y. H. Clinical study of Zhengqing Fengtongning in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis and its effect on cytokines. Contemporary Medicine . 2013;19(12):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng C. E., Liu Y. C., Zhang F. Clinical study of glucosamine sulfate combined with Zhengqing Fengtongning in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Research of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine . 2014;6(3):123–125. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Q. Y. Clinical effect of Zhengqing Fengtongning on knee osteoarthritis and its effect on cytokiness. Chronic Pathematology Journal . 2016;17(9):972–975. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu B., Zhong Q. H., Xun D. Efficacy of loxicam combined with Zhengqing Fengtongning in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis and its effect on serum inflammatory indexes. Heilongjiang Medicine Journal . 2017;30(1):120–122. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C. C., Li M. Z., Gao Z. M. Analysis of the short-term efficacy of Zhengqing Fengtongning combined with sodium hyaluronate injection in the treatment of knee arthritis. Pharmacology and Clinics of Chinese Materia Medica . 2017;33(3):195–198. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo H. C., Ou D. M. Clinical effect of sinomenine combined with diacetacin in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Chinese Traditional Patent Medicine . 2018;40(8):1894–1896. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo H. C., Hu D. H. Efficacy and safety of glucosamine hydrochloride combined with sinomenine in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Chinese Traditional Patent Medicine . 2019;41(3):708–710. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mi Z. Y. Clinical effect analysis of Zhengqing Fengtongning release tablets combined with Shuangqiurein Capsule on patients with knee osteoarthritis. Chinese Community Doctors . 2019;35(25):98–100. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang G. L. Clinical observation of Zhengqing Fengtongning release tablet in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Medical Diet and Health . 2019;14108 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Q., Chen W. Y. Observation on the curative effect of Zhengqing Fengtongning release tablets combined with diacerein in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Drugs & Clinic . 2019;34(2):477–480. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y., Liu F. R., Gu C. H. A randomized parallel control study of Zhengqing Fengtongning combined with sodium hyaluronate in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Journal of Practical Traditional Chinese Internal Medicine . 2019;33(4):59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J. Clinical effect of Zhengqing Fengtongning on degenerative knee arthritis. Inner Mongolia Journal of TCM . 2021;40(7):32–33. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yv Z., Xv Y., Zang Y. S. Application of Zhengqing Fengtongning release tablets in the treatment of 41 cases of knee osteoarthritis. World Latest Medicine Information . 2021;21(53):225–227. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hopp L. Risk of bias reporting in cochrane systematic reviews. International Journal of Nursing Practice . 2015;21(5):683–686. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J. L., Rong S., Zhou Z. The efficacy and safety of acupuncture for treating osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture- (OVCF-) induced pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med . 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/8574621.8574621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cordero C. P., Dans A. L. Key concepts in clinical epidemiology: detecting and dealing with heterogeneity in meta-analyses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology . 2021;130:149–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hui W. Q., Wang X. X., Wang J. Research progress on natural components, clinical application and adverse reactions of Sinomenium acutum. Journal of Modern Medicine & Health . 2019;35(19):2989–2993. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng J., Wang R. H., Kou S. D. Effects of sinomenine on expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and nerve growth factor in cartilage and synovial membrane of rabbit knee osteoarthritis model. Chinese Journal of Information on TCM . 2016;23(3):38–41. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The table data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article. The figure data used to support the findings of this study are included within the figure files.