Significance

Studies to date have focused on the impact of border walls on national security, transborder crime, and the environment. This study addresses how border walls affect the way a country is viewed by the citizens of other countries, all else being equal. Using an experimental design that is replicated in the United States, Ireland, and Turkey, we find that the presence of walls on borders harms countries’ international image. This is especially true if the country is known to have been the builder of the wall. Walls also lower evaluations of the bordering countries’ bilateral relationship. Although the presence of a wall increases perceptions of a country’s border security, paradoxically it lowers the perceived security of people within the country.

Keywords: borders, soft power, international relations

Abstract

This study assesses the impact of international border walls on evaluations of countries and on beliefs about bilateral relationships between states. Using a short video, we experimentally manipulate whether a border wall image appears in a broader description of the history and culture of a little-known country. In a third condition, we also indicate which bordering country built the wall. Demographically representative samples from the United States, Ireland, and Turkey responded similarly to these experimental treatments. Compared to a control group, border walls lowered evaluations of the bordering countries. They also signified hostile international relationships to third-party observers. Furthermore, the government of the country responsible for building the wall was evaluated especially negatively. Reactions were consistent regardless of people’s predispositions toward walls in their domestic political context. Our findings have important implications for a country’s attractiveness, or “soft power,” an important component of nonmilitary influence in international relations.

Within the past 10 years, states around the world have accelerated the use of border walls and fences for purposes of border management and control. Much has been written about the cost and effectiveness of border walls, but no evidence-based research exists about their psychological impact. This study addresses the impact of border walls on third-party evaluations of countries and on perceptions of the quality of international relationships between neighboring states.

Our main hypothesis is that those who are aware that a border wall exists between two countries will rate the neighboring states as having worse relations than would otherwise be the case. In addition, they will evaluate states with border walls more negatively than those without them. This potential effect is important because international relations are thought to be influenced by the “attractiveness” of states and their societies, a phenomenon that international relations scholars refer to as “soft power” (1, 2). Countries that are viewed positively by the citizens of other countries benefit from greater credibility and influence in international relations (1). Thus, scholarship on soft power focuses on factors that may positively or negatively affect perceptions of one country in the eyes of citizens of other countries. Because ordinary citizens often lack much information about other countries, they tend to rely on highly visible cues when making such judgments. In this study, we hypothesize that one such cue is a country’s border infrastructure.

Borders, Walls, and Soft Power

Almost all of the studies of border infrastructure to date address how border infrastructure affects national security or transborder crime (3). Some find that border barriers have highly conditional security effects (4), undesired environmental impacts (5), and unanticipated economic consequences (6). The study of psychological impacts of border walls has been limited to the effects on proximate inhabitants, which is quite distinct from the third-person perspective in our study. For example, Berliners and other East Germans experienced what psychologist Dietfried Müller-Hegemann (7) called a “wall-disease” from their enclosure experience. A recent study in Northern Ireland suggests that psychological maladies in walled border communities—from depression to alcoholism—result from a sense of separation (8). However, studies have not considered the impact of border infrastructure on a country’s international image, which is the central focus in this study.

The recently accelerating phenomenon of border hardening merits investigation for its potential implications for international relations (9). Our goal is to assess the inferences people draw from the existence of border walls, abstracted from border politics in people’s own countries, and independent of partisan cues. We seek to understand the psychological inferences that people draw from the sheer existence of a barrier between states when walls per se are not the focus of attention or political controversy.

Among its own citizens, assessments of a country’s international standing tend to be rooted in domestic politics. For example, among Americans, opinions about a wall along the southern US border are highly partisan. Currently, there is tremendous support among Republicans and greater opposition from Democrats (10). In contrast, our research question is how citizens of other countries view the same country with and without a border wall.

Our research speaks directly to the issue of soft power, but it does so more systematically than the public opinion literature (11) or discourse analysis (12), of which both face significant inferential limitations. As the originator of the concept has recently emphasized, soft power rests on foreign perceptions of the relative attractiveness of a society’s culture, its foreign policy, and its values (13). As such, foreign perceptions of another country’s attractiveness are central to the concept of soft power. The problem has always been how to measure such perceptions. The “Soft Power 30 Index” (SPI-30) is one such effort, but this index relies primarily on data its creators have gathered from other sources. Based on survey data, the SPI-30 finds that “friendliness” and “foreign policy” are strongly related to respondents’ claims of attraction to a foreign country and asserts that a country’s level of global “engagement”* should be weighted most strongly. We incorporate these insights into our experimental research, avoiding measures that make untested assumptions about elements of soft power as well as the problems of constructing a valid comparative global index (14).

Our goal is to draw strong inferences about soft power in response to one of the most visible and controversial foreign policy actions taken by states in recent years, namely, the erection of border walls with neighbors. To do so in a way that allows strong causal inferences, we use an experimental design involving countries about which our respondents have little preexisting knowledge. In addition, we utilize demographically representative nonprobability samples of participants drawn from three different countries, each with differing domestic predispositions toward border walls.

Theory and Expectations

Our expectations are based in part on automatic, well-documented psychological reactions to spatial distance and separation and in part on the kinds of cognitive inferences we expect people to make about the presence of walls on international borders. First, it is well-established that primitive human perceptual processes are rooted in spatial relations, which are among the most basic of psychological constructs (15). Physical distance serves as the foundation for human understanding of psychological distance (16). To be close to or distant from an entity naturally confounds having it within one’s field of view with one’s psychological distance from it. Things that are unseen are automatically construed as both more psychologically and socially distant. Physical distance and visual separation can influence both people’s judgments and their affect toward what is on the other side.

Research shows that walls manipulate perceptions of space. When barriers separate objects so that people cannot see what is on the other side, this changes observers’ mental estimates of the distance between those entities (17). Because spatial perception and psychological distance are tightly intertwined in the human mind, spatial distances can be systematically distorted by social distance and vice versa (18). For example, lower emotional involvement with a city leads people to estimate that the city is further away (19).

These reciprocal effects among different dimensions of distance—social, psychological, and physical—also manifest themselves in affective reactions to close and distant targets. Close physical distance tends to activate empathic reactions that characterize affectively close relationships even when the relationship itself is held constant (20). When primed to think in terms of distance as opposed to proximity, people provide weaker, less positive reports of emotional attachments (21). We hypothesize that border structures between countries will be interpreted by observers as indicative of greater psychological distance between the countries and in turn will lead to more negative inferences about the relationship between two neighboring countries.

In addition to the information conveyed automatically by visual separation, citizens may react cognitively based on their understanding of why states erect walls. Walls are typically built to keep out what is on the other side, often to satisfy a domestic constituency who may be unlikely to think about how people in third-party countries will view this action. We expect that the country to whom the act of distancing is attributed will be viewed especially negatively in light of this information. Despite Robert Frost’s poetic line that good fences make good neighbors, we would draw a contrary lesson from one of the most notorious modern efforts to use walls to “secure” and separate, namely, the Berlin Wall. At least one study suggests that the wall was ideologically potent enough to help convert Germany into a victim of Soviet control in the eyes of many if not most Europeans (22). Conversely, when the wall fell in 1989, it was described by third-party observers in Britain as “one of the most joyful events ever witnessed by the world” (22). Of course, not all border walls carry the emotional freight of the Berlin Wall. Nonetheless, from the perspective of third parties, we expect that walls will be viewed as hostile international structures even if they are also viewed as security enhancing. To the extent that a country putting up a wall is viewed by other countries as more hostile and difficult to get along with, international attitudes toward that country may shift in a negative direction, directly degrading a state’s soft power. If so, building walls may have important consequences for international relations that go well beyond effects on the immediate bordering countries.

Finally, we predict that these results will hold regardless of people’s opinions about border walls within their own country and regardless of their proximity to their own national borders. Domestic support for walls may stem from partisan cues and geographic locations as well as assumptions about what they will accomplish. But when judging other countries about which they have little to no knowledge, we predict that building walls will be seen as hostile and contribute to more negative attitudes toward the wall-building country in particular.

Research Design

To test the generalizability of these hypotheses, we fielded the same experiment in three very different contexts, as follows: the United States, Ireland, and Turkey. In the United States, border issues are highly salient, partisan, and increasingly controversial. The Republic of Ireland’s border with Northern Ireland has a troubled history of localized violence which was only settled in 1997. Walling and fencing has been removed between most of the Republic and the North. Much Irish opposition to Brexit stemmed from a desire to avoid rebuilding border infrastructure (23). Of these three countries, Turkey may be most positively predisposed toward walls since for more than a decade, Turkey has faced a civil war to its southeast in Syria, periodic cross-border Kurdish terrorism, and the recent rise and decline of the Islamic “State” (ISIS) in neighboring Iraq. In this context, a wall could be interpreted by our Turkish respondents as protective.

All respondents in these experimental studies viewed a 3.5-min video entitled “Countries of the World: Tajikistan.”† The video purported to be part of an educational series on little-known countries. It featured still photos and video segments with music and narration throughout. All three versions were identical in describing the geography, natural resources, history, sports, foods, and holidays of Tajikistan, the central topic of the video. Respondents were told they would be evaluating the video as an educational tool. They were asked factual questions about what they had learned after viewing.

Respondents were randomly assigned to one of three versions of the treatment. At one point in the video, the narrator mentions that Tajikistan shares a border with neighboring Kyrgyzstan. In the “no-wall” (control) condition, the narrator refers to the border, and a valley between two mountains is shown. In the “wall” condition, when the border between Tajikistan and its neighbor is mentioned, it is called a “border wall,” and a picture of a wall is shown instead of the valley. In the third condition, “wall built by Kyrgyzstan,” the same visuals are shown as those in the wall condition, but the narrator mentions in passing that the wall was originally built by Kyrgyzstan, the neighboring country.

Our hypotheses were identical across representative samples of the United States, Turkey, and Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Hypothesis 1. The wall condition will lower overall evaluations of both countries relative to the no-wall (control) condition. The pretreatment survey asked respondents, in the following question, to rate on a 7-point scale a list of four countries, among which Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan were included: “Based on what you know, what is your general impression of each of the following countries?” The same question was asked posttreatment. This approach made it possible to control for the effects of the video content, which was otherwise constant across conditions, while evaluating the impact of the experimental treatment.

Hypothesis 2. Respondents assigned to the wall condition will view the bilateral relationship between the two countries more negatively than those in the no-wall condition. A series of nine questions asked about the quality of the countries’ relationship, for example, whether the two countries trust one another, trade with one another, and so forth (SI Appendix). Because these measures were strongly intercorrelated, they were combined into a highly reliable additive index of the quality of the bilateral relationship, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.91 to 0.92 across the three countries. We expected the bilateral relationship to be more positive for those in the no-wall (control) group than those assigned to the wall conditions.

Hypothesis 3. Relative to respondents in the wall condition, those assigned to the wall built by Kyrgyzstan condition will view the government of Kyrgyzstan less positively relative to the government of Tajikistan. To test this expectation, two separate but parallel series of questions were asked about the government of each country. Each formed a reliable index of attitudes toward the country’s government (details in SI Appendix). Scores were differenced, with higher scores reflecting the view that Tajikistan’s government is superior to Kyrgyzstan’s government. Thus, a higher score in the wall condition would suggest that respondents are “punishing” the government of Kyrgyzstan with lower evaluations when told that Kyrgyzstan is responsible for building the wall.

Additional features of the study helped to ensure consistent and credible results across countries. First, with the exception of questions relating to political identity/affiliation, identical questions and response scales were used across all three experiments. Second, manipulation checks in all three experiments confirmed that respondents in the treatment conditions did, in fact, notice the information pertaining to our experimental treatments (SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S3). These questions were asked after the dependent variables to avoid calling attention to the treatments. Although the wall visuals were shown for less than 10 seconds in total and were only mentioned in passing by the narrator, the visual wall cue effectively communicated the presence of a wall on the border. Indicating the wall was built by Kyrgyzstan was more subtle but still produced a significant manipulation. To facilitate comparisons of effect sizes across countries, dependent variables were rescaled to range from 0 to 1. All three samples were over n = 1,000 and demographically representative of their respective countries (details in SI Appendix).

Results

Hypothesis 1 suggests that the presence of a wall will lower overall evaluations of both countries. This hypothesis was tested using a mixed model ANOVA including a repeated-measures main effect for exposure to the video and a between-group factor representing random assignment to the wall condition or the no-wall condition. Confirmation of a differential change from watching the two videos was evaluated using the interaction between the pre- to posttreatment and whether the video condition included a wall or not (SI Appendix, Table S1).

Fig. 1 shows the effects of the wall treatment on evaluations of Tajikistan (Left) and Kyrgyzstan (Right) for each of the three experiments. The constant material in the videos—about the people and customs of this little-known country—generally improved attitudes toward both countries. In the United States and Ireland, most respondents started out the experiment near the midpoint of the scale in their evaluations, consistent with little relevant foreknowledge. Turkey, in contrast, registered somewhat more positive views of these countries.

Fig. 1.

Effects of the presence of a wall versus no wall on evaluations of Tajikistan (Left) and Kyrgyzstan (Right), by nationality of respondents. All six analyses demonstrate significant interactions between pre- to posttreatment change and presence of the wall (P < 0.001), in addition to a main effect of viewing the video (P < 0.001). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Details are provided in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Most importantly, the expected interaction is supported in all six cases, with differential increases by experimental condition (SI Appendix, Table S1). Overall impressions of Tajikistan were roughly equivalent pretreatment, but by posttreatment, impressions of Tajikistan had grown more positive in the no-wall condition than in the wall condition. On average, the presence of the wall lowered the positivity of evaluations of Tajikistan by around 7 to 8% in the United States and Ireland and by around 4% in Turkey. The finding of differential pre- to posttreatment change based on whether respondents saw a wall or not is remarkably consistent across all three countries.

The wall condition reduced positive evaluations of Kyrgyzstan even more. The average effect size in the United States, Ireland, and Turkey was 12, 10, and 5%, respectively. In all three countries, there was a significant interaction between the extent of pre- to posttreatment change and experimental condition.

Hypothesis 2 evaluates the impact of a wall on perceptions of the quality of the bilateral relationship (SI Appendix, Table S2). Overwhelmingly, those who viewed the no-wall condition inferred that the relationship between the two countries was more positive and cooperative than those who viewed the wall condition. As shown in Fig. 2, the size of these effects is substantial. On average, showing just a few seconds of wall in the video lowered assessments of Tajikistan’s and Kyrgyzstan’s bilateral relationship by 15% in the United States, 14% in Ireland, and 12% in Turkey. Countries bordered by walls are seen as less likely to engage in successful relationships with neighboring countries.

Fig. 2.

Effects of the presence of a wall versus no wall on perceptions of bilateral relations, by nationality of respondents. The main effects of a wall versus no wall were significant in all three country analyses (P < 0.001). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Details are provided in SI Appendix, Table S2.

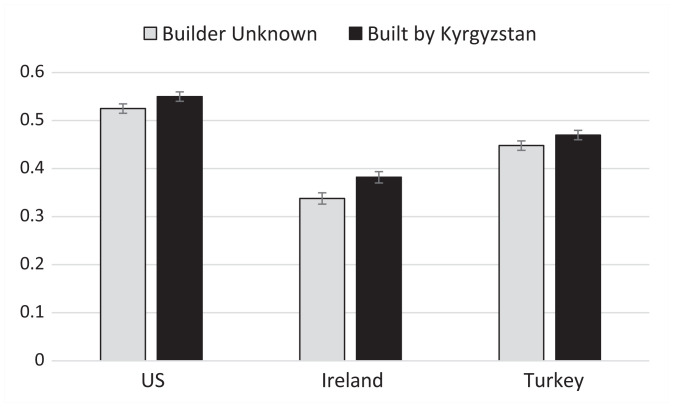

Finally, do respondents downgrade their impression of the government of Kyrgyzstan relative to Tajikistan under the wall built by Kyrgyzstan condition (hypothesis 3)? As illustrated in Fig. 3 and confirmed by the analyses in SI Appendix, Table S3, in each of the three comparisons, evaluations of Tajikistan’s government are systematically and significantly higher than those of Kyrgyzstan when people were told that Kyrgyzstan was responsible for building the wall. This is especially notable given that in the wall condition that serves as the basis for comparison, the builder is not specified, but could be either country.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of perceived superiority of Tajikistan’s government to Kyrgyzstan’s government, by wall condition versus the wall built by Kyrgyzstan. All three comparisons are significantly different, with F = 10.97, 26.43, and 8.46, respectively. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Details are provided in SI Appendix, Table S3.

We next examined whether the documented reactions to walls varied by respondents’ domestic political leanings that might predispose them to favor or oppose walls. While Democrats and Republicans feel very differently about walling the US southern border with Mexico (24), we found that both Democrats and Republicans responded equally negatively to the wall treatments in these videos compared to the no-wall condition and equally negatively toward Kyrgyzstan when given the information that Kyrgyzstan had built the border wall with Tajikistan. We also found similar results in Ireland for both supporters and opponents of Brexit with its politically salient implications for the Irish border. Results were also similar across parties in Turkey, even those most closely identified with Kurdish interests, whose communities may have been most impacted by the wall on Turkey’s southeastern border. When viewed from the perspective of a third-party observer, powerful political orientations have relatively little impact on how border walls are interpreted.

Finally, some research suggests that geographic context matters for attitudes about border security (25). To investigate this possibility, in each of the three countries, respondents’ latitudes and longitudes were used to calculate how far the respondent was from an international border in their own country. We then divided respondents into those above or below the median distance from an international border and looked for interactions between distance and each of our experimental treatments. In no case did we find evidence of significant interactions between the experimental treatments and geographic distance.

Discussion

Border walls affect observers’ perceptions of states in consistently negative ways. Not only is this finding the case across very different countries in fundamentally different contexts, but it is also stable regardless of the respondent’s preexisting political views and their distance to an international border. In all three countries, no matter people’s politics or within-country location, the presence of border infrastructure lowered evaluations of the countries and eroded perceptions of the quality of their international relationships. If a country was perceived to be responsible for erecting the wall, it was viewed especially negatively. Turkish respondents demonstrated a consistent pattern of smaller effects than the other countries, although these differences were not statistically significant. This pattern most likely results from the fact that Turkish respondents had prior opinions of these countries.

How do we reconcile these findings with the apparent domestic political enthusiasm for walls around the world? In the United States, people seem quite capable of interpreting walls on their country’s own borders differently from those between other countries. Highly polarized opinions about the desirability of walls can obviously coexist along with negative reactions when other countries put them up. Our results show that in the absence of partisan cues, people fall back on basic understandings of what walls and physical distancing represent. The presence of a wall signaled unfriendliness and a motive to create distance from the neighboring country. People interpreted a border wall as indicating a preference or desire to separate from the neighboring country.

This interpretation is supported by the treatment that informed respondents about which country built the wall. Exposed to the same visual image, respondents systematically and consistently downgraded the builder. There is no change in visual perspective between the wall condition and the Kyrgyzstan built the wall condition, which suggests that automatic psychological reactions get us only part way toward understanding how walls affect more complex political judgments. Across all three countries, respondents made the additional cognitive judgment that a state responsible for distancing (Kyrgyzstan built the wall) is less attractive than it would otherwise be (e.g., in the wall condition). In other words, people in all three countries judged the experimental video’s representation of border walling to be an unfriendly gesture,‡ one that led them to downgrade their opinion of Kyrgyzstan relative to Tajikistan.

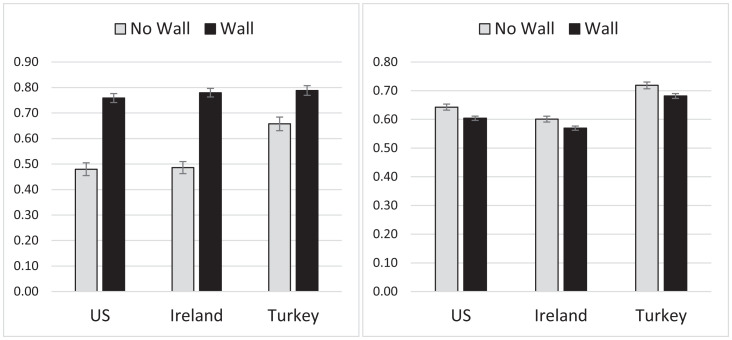

At the same time, border walls do appear to positively affect perceptions of border security. When respondents in these experiments were asked, “How strong is border security between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan?”, they consistently judged border security as stronger in the two wall conditions than that in the no-wall condition (Fig. 4, Left). The effect was substantial, ranging from 13 to 29 percentage points higher in the wall conditions across the three countries.

Fig. 4.

Perceived strength of border security (Left), and perceived level of personal security (Right), by wall versus no-wall conditions. On the Left, all three country comparisons are significantly different (P < 0.001), with F = 320.73, 395.46, and 61.59, respectively. On the Right, all three countries are also significantly different, with F = 9.03 (P < 0.05), 6.20 (P < 0.01), and 6.56 (P < 0.05), respectively. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Details are provided in SI Appendix, Tables S4 and S5.

However, when these same respondents were asked about the personal safety of those living in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan (“How safe do you think the people are from violence and crime?”), the wall treatment had precisely the opposite effect (Fig. 4, Right). Those assigned to the wall conditions consistently assumed the people in these countries had significantly less personal safety than those in the no-wall condition. Although this may seem counterintuitive, there is a clear logic to their inferences, as follows: just as the presence of police in a neighborhood may suggest something illegal is afoot, respondents who saw a wall in the video inferred that there were security issues of some kind that necessitated a border wall. Political rhetoric suggesting that walls are necessary for purposes of keeping criminals out has been prominent in the United States (26), but it is surprising to see this same reaction of essentially the same size across all three countries.

Interestingly, the negative effect of the wall condition applies to people as well as governments. To probe perceptions of each society we asked the following: “How favorable or unfavorable is your view of everyday people in [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan, the country to the north of Tajikistan]?” A parallel question was asked about governments and political leaders. We averaged assessments of people and of governments across both countries and pooled the results for the American, Irish, and Turkish samples. Respondents were significantly more likely to view Tajikistan’s people unfavorably in the wall treatment, as was the case for evaluations of the government (SI Appendix, Table S6). The video did not explicitly say that the state constructed the border wall. It is thus somewhat surprising that respondents judged “the people” just as harshly as they did “political leaders” for the border barrier in these videos.

Broader Implications

Our findings speak directly to the impact of border security policies on soft power. Three decades ago, Joseph Nye claimed that soft power was almost as important as hard (military) power. While scholars have pointed to factors that make a country attractive to others, our research suggests that repulsion may be important to keep in mind as well. Moreover, while most research on soft power focuses on broad traits that are not readily manipulable policy levers (the quality of institutions and entrepreneurialism), our results suggest that there are some very specific policies that catalyze strong negative attitudes. Such strong negative attitudes may inhere in the hostile signal that borders walls send to neighbors, potentially impacting such important outcomes as bilateral trade (6). Indeed, recent research has suggested that desecuritization—playing down the security aspects of infrastructure—can be a soft power strategy (27). We do not argue there is an inevitable tradeoff between hard and soft power, but it is important to appreciate the possibility that some symbolic security measures may well reduce a state’s attractiveness more than they enhance national security.

Our results imply that if policymakers do care about soft power (and they seem to; refs. 28, 29), they should consider the potential damage border walls may have on a nation’s image. This is quite important since in many cases border walls are of questionable economic (30), immigration (31), crime fighting (32), public health (33), or security benefit (4). Whatever advantages flow from border walls should be balanced against the unfavorable perceptions that the builder is likely to garner. While we are not the first to associate “friendlier” border policies with soft power (e.g., ref. 34), our findings speak scientifically to this possibility.

Materials and Methods

Data.

The survey experiments were administered in the United States from October 24 to 31, 2019 (n = 1,022); in Ireland from March 20 to 26, 2020 (n = 1,108); and in Turkey from September 1 to 15, 2020 (n = 1,025). In all three countries, respondents were recruited by Forthright, Inc. Experimental samples were constructed to be demographically representative of their respective countries on gender, age, race/ethnicity, and region, although they were not acquired using probability sampling methods.

Measures.

Evaluations of countries (pre- and posttreatment).

“Based on what you know, what is your general impression of each of the following countries?” [7-point scale, high = positive]. Countries included France, Italy, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Perceived strength of border security.

“How strong is border security between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan?” [5-point scale, rescaled to 0 to 1].

Perceived personal security.

“How safe do you think the people of [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan] are from violence and crime?” [5-point scale]. Answers to both questions were averaged and then rescaled to range from 0 to 1.

Bilateral relations between countries.

Each item below was measured on a 5-point scale in which high = positive relationship. A highly reliable additive index produced a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 in the United States, 0.92 in Ireland, and 0.91 in Turkey. For ease of interpretation, the index was rescaled to vary between 0 and 1.

-

1.

Would you say that relations today between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are very good, somewhat good, neither good nor bad, somewhat bad, or very bad?

-

2.

Would you say that Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are friendly or unfriendly toward one another?

-

3.

How much do you think the people in these two countries trust one another?

-

4.

How likely are Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to trade with one another?

-

5.

How likely are the governments of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to cooperate with one another?

-

6.

How easy do you think it is for the people in these two countries to visit one another?

-

7.

To the best of your knowledge, are Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan allies, enemies, or something in between?

-

8.

How much do you think the people in these two countries like or dislike each other?

-

9.

How strong is border security between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan?

Superiority of government of Tajikistan relative to Kyrgyzstan.

Two additive indexes were created, namely, one for evaluations of Tajikistan and one for Kyrgyzstan. The reliabilities of the Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan indexes, respectively, were as follows: US respondents, 0.87, 0.90; Irish respondents, 0.87, 0.90; and Turkish respondents, 0.91, 0.92. The difference (Tajikistan – Kyrgyzstan) provides a measure of the perceived superiority of Tajikistan’s government. All questions were asked separately in a random order on 1 to 5 scales. The index was rescaled to range between 0 and 1.

-

1.

How favorable or unfavorable is your view of the government and political leadership of [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan]?

-

2.

How much do you think the government of [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan] respects individual human rights?

-

3.

How much freedom do you think people in [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan] have to come and go as they please?

-

4.

How much freedom do you think people in [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan] have to criticize their government when they feel it is appropriate?

-

5.

To what extent is [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan] open or closed off to people who want to visit from outside their country?

-

6.

So far as you know, how does [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan] feel about its neighboring countries?

-

7.

How safe do you think the people of [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan] are from violence and crime?

-

8.

How likely is it that [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan] tries to promote peace between nations?

-

9.

How likely is it that the government of [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan] wants to cooperate with other countries?

Evaluations of people.

“How favorable or unfavorable is your view of everyday people in [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan]?” The 5-point scales were combined and rescaled to 0 to 1.

Evaluations of government.

“How favorable or unfavorable is your view of the government and political leadership of [Tajikistan/Kyrgyzstan]?” The 5-point scales were combined and rescaled to 0 to 1.

Institutional Review Board Review.

This study was judged to be exempt from the need for review due to minimal risk to participants under protocol number 833165. Participants in all three countries were paid through Forthright, a survey research company. Informed consent was obtained. Protocols for human participant protections were followed for each country. All data were made anonymous and untraceable before the research firms delivered them to the authors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Anna Gamarnick and Waldo Aguirre for producing the experimental videos and Alex Tolkin and Tyler Leigh for their help in identifying material for inclusion. We thank Elizabeth Martin for her assistance with statistical analysis of the experimental results and Zuha Noor and Burcu Kolcak for assistance with translation to Turkish. Michael Kenwick, Mert Moral, Meltem Muftuler-Bac, Brendan O’Leary, and Lauren Pinson provided helpful insights on country context, survey wording, and research design. We also thank the Borders and Boundaries research group at the University of Pennsylvania for helpful reactions to an early version of this project and participants at the Borders Conference at Perry World House, University of Pennsylvania, for comments. We acknowledge funding from Carnegie Corporation of New York Grants 18-56213 (B.A.S.) and 17-54246 (D.C.M.).

Footnotes

Reviewers: D.C., Washington University in St. Louis; and R.M., Brown University.

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2117797119/-/DCSupplemental.

*According to the index’s published methodology, “engagement” includes “metrics such as the number of embassies/high commissions a country has abroad, membership in multilateral organisations, and overseas development aid” (14, 30).

†The treatment condition videos can be found here: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EXPXCT.

‡It is possible that a colorfully painted wall would have a different effect. See https://www.serargentino.com/gente/lo-peor-de-nosotros/el-muro-de-donald-trump-pero-en-misiones. But this experiment did not test for variation in border walls aesthetics.

Data Availability

Anonymized experimental data and videos have been deposited in Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EXPXCT) (35).

References

- 1.J. S. Nye, Jr., Soft power. Foreign Policy 80:153–171 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson E. J., Hard power, soft power, smart power. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 616, 110–124 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avdan N., Gelpi C. F., Do good fences make good neighbors? Border barriers and the transnational flow of terrorist violence. Int. Stud. Q. 61, 14–27 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linebarger C., Braithwaite A., Do walls work? The effectiveness of border barriers in containing the cross-border spread of violent militancy. Int. Stud. Q. 64, 487–498. (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rea P., Nature divided, scientists united: US–Mexico border wall threatens biodiversity and binational conservation. Bioscience 68, 740–743 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter D. B., Poast P., Barriers to trade: how border walls affect trade relations. Int. Organ. 74, 165–185 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller-Hegemann D., Die Berliner Mauer-Krankheit: Zur Soziogenese Psychischer Störungen (Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1973). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maguire A., French D., O’Reilly D., Residential segregation, dividing walls and mental health: a population-based record linkage study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 70, 845–854 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simmons B. A., Kenwick M., Border orientation in a globalizing world: Concept and measurement. Am. J. Pol. Sci., in press. Published December 22, 2021 (early view) available at https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ajps.12687__;!!IBzWLUs!CGpFKf4SrxVWO7xpUIbvQNIPtZEfMQxCLdfKOsIIpsF5GySmdNiAb_Ju7DcntQ$ [Google Scholar]

- 10.“Public opinion on a Southern-border wall in the U.S., by political party” (Statista Research Department, March 11, 2020). https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.statista.com/statistics/798252/support-for-southern-border-wall-in-the-us/__;!!IBzWLUs!CGpFKf4SrxVWO7xpUIbvQNIPtZEfMQxCLdfKOsIIpsF5GySmdNiAb_L3iGr1QA$. Accessed 31 December 2021.

- 11.Shi T., Lu J., Aldrich J., Bifurcated images of the US in urban China and the impact of media environment. Polit. Commun. 28, 357–376 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayden C., The Rhetoric of Soft Power: Public Diplomacy in Global Contexts (Lexington Books, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nye J. S., American democracy and soft power. Project Syndicate (2021). https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/american-democracy-and-soft-power-by-joseph-s-nye-2021-11. Accessed 31 December 2021.

- 14.McClory J., The Soft Power 30: A Global Ranking of Soft Power 2019 (USC Center on Public Diplomacy, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark H. H., “Space, time, semantics, and the child” in Cognitive Development and Acquisition of Language, Moore T., Ed. (Elsevier, 1973), pp. 27–63. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trope Y., Liberman N., Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 117, 440–463 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman J. F., Miller B. S., Heins J. A., Barriers and spatial representation: Evidence from children and adults in a large environment. Merrill-Palmer Q 33, 53–68. (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Won A. S., Shriram K., Tamir D. I., Social distance increases perceived physical distance. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 9, 372–380 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekman G., Bratfisch O., Subjective distance and emotional involvement. A psychological mechanism. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 24, 430–437 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiano Lomoriello A., Meconi F., Rinaldi I., Sessa P., Out of sight out of mind: Perceived physical distance between the observer and someone in pain shapes observer’s neural empathic reactions. Front. Psychol. 9, 1824 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams L. E., Bargh J. A., Keeping one’s distance: The influence of spatial distance cues on affect and evaluation. Psychol. Sci. 19, 302–308 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michail E., After the war and after the wall: British perceptions of Germany following 1945 and 1989. J. Contemp. Hist. 3, 1–12 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gormley-Heenan C., Aughey A., Northern Ireland and Brexit: Three effects on ‘the border in the mind’. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 19, 497–511 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cortina J., From a distance: Geographic proximity, partisanship, and public attitudes toward the US–Mexico border wall. Polit. Res. Q. 73, 740–754 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gravelle T. B., Politics, time, space, and attitudes toward US–Mexico border security. Polit. Geogr. 65, 107–116 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis J., Walls work: Historic successes point the way toward border barriers of the future. CBP Archive (2018). https://www.cbp.gov/frontline/border-security. Accessed 31 December 2021.

- 27.Jakimów M., Desecuritisation as a soft power strategy: The Belt and Road Initiative, European fragmentation and China’s normative influence in Central-Eastern Europe. Asia Eur. J. 17, 369–385 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albert E., China’s Big Bet on Soft Power (Council on Foreign Relations, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rugh W., American soft power and public diplomacy in the Arab world. Palgrave Commun. 3, 16104 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen T., de Castro Dobbin C., Morten M., Border Walls (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schon J., Leblang D., Why physical barriers backfire: How immigration enforcement deters return and increases asylum applications. Comp. Polit. Stud. 54, 2611–2652. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Getmanski A., Grossman G., Wright A. L., Border walls and smuggling spillovers. Quart. J. Polit. Sci. 14, 329–347 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruch J. D., Barin O., Venkataramani A. S., Song Z., Mortality before and after border wall construction along the US-Mexico border, 1990-2017. Am. J. Public Health 111, 1636–1644 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirisci K., A friendlier Schengen visa system as a tool of soft power: The experience of Turkey. Eur. J. Migr. Law 7, 343 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 35.D. C. Mutz, B. S. Simmons, Replication data and videos for "The psychology of separation: border walls, soft power, and international neighborliness." Harvard Dataverse, V3. 10.7910/DVN/EXPXCT. Deposited 21 June 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized experimental data and videos have been deposited in Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EXPXCT) (35).