Significance

We study the impact of crisis on information seeking in authoritarian regimes. Using digital trace data from China during the COVID-19 crisis, we show that crisis motivates citizens to seek out crisis-related information, which subsequently exposes them to unrelated and potentially regime-damaging information. This gateway to both current and historically sensitive content is not found for individuals in countries without extensive online censorship. While information seeking increases during crisis under all forms of governance, the added gateway to previously unknown and sensitive content is disproportionate in authoritarian contexts.

Keywords: censorship, political science, political communication

Abstract

Crisis motivates people to track news closely, and this increased engagement can expose individuals to politically sensitive information unrelated to the initial crisis. We use the case of the COVID-19 outbreak in China to examine how crisis affects information seeking in countries that normally exert significant control over access to media. The crisis spurred censorship circumvention and access to international news and political content on websites blocked in China. Once individuals circumvented censorship, they not only received more information about the crisis itself but also accessed unrelated information that the regime has long censored. Using comparisons to democratic and other authoritarian countries also affected by early outbreaks, the findings suggest that people blocked from accessing information most of the time might disproportionately and collectively access that long-hidden information during a crisis. Evaluations resulting from this access, negative or positive for a government, might draw on both current events and censored history.

Scholars have long predicted that during crises or uncertain time periods, people will rely more on mass media for information relevant to their own safety and spend more time seeking out information (1). Increased attention to media during crisis has been shown empirically in democracies, such as during democratization in Eastern Europe (2), during the eruption of Mount St. Helens (3), and immediately after the September 11 terrorist attacks (4–6). Increased attention to the media presents opportunities for large changes in opinion or political socialization (2, 7), and crisis disruptions can also shift attention toward entertainment due to lack of mobility and boredom (8).

This paper identifies another effect of crisis: abrupt exposure to prior sensitive information blocked by governments. We examine the effect of crisis on information seeking in highly censored environments by studying the impact of the COVID-19 public health crisis on censorship circumvention in China. In January and February of 2020, COVID-19 cases in China were spiking, official news sources were slow to acknowledge the crisis, and many regions of China restricted movement. Using a variety of measures of Twitter and Wikipedia data, both of which are inaccessible within China, we show large and sustained impacts of the crisis on circumvention of censorship in China. For example, the number of daily, geolocating users of Twitter in China increases by up to 40% during the crisis and is 10% higher long term, while politically sensitive accounts gain tens of thousands of excess followers, up to 3.8 times more than under normal circumstances, and these followers persist 1 y after the crisis’s end. Moreover, beyond information seeking about the crisis itself, we find that information seeking across the Great Firewall extended to information the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long censored, including information about sensitive historical political events and leaders.

Although just one of many crises, the global nature of the COVID-19 crisis makes this case a unique and important opportunity to compare information seeking during crisis in China to that in other countries that had similar COVID-19 outbreaks. To draw a comparison, we investigate the same patterns in countries with no censorship or in authoritarian regimes where the platforms we study are not censored that also experienced large outbreaks of COVID-19 cases soon after China. Consistent with other work on information seeking during lockdown in democracies (8), we find higher levels of engagement with online news media generally in comparison countries, but do not observe users seeking information about sensitive political topics unrelated to the crisis.

Together, these findings demonstrate that during crisis access to information fundamentally changes in autocracies in patterns that differ from democracies. Information spillovers originating from crisis could be especially pronounced when a regime has previously censored a large amount of political information and circumvention tools provide access to a wide variety of current and historical censored content. That information seeking during crisis spills over to unrelated and previously censored content in authoritarian contexts is related to previously studied gateway effects where the Chinese government’s action to suddenly block a primarily entertainment website facilitated access to censored political information (9). However, our overall results and country comparisons suggest a broader implication: that the abrupt and wide-ranging consumption of hidden information may be a feature of censorship regimes themselves and can occur with or without contemporaneous government action to bring it about. This spillover effect is further robust enough that an ongoing crisis does not appear to distract from long-censored information—attention to information expands to include both the crisis and censored history. These results provide an important contribution to the literature on the impacts of crisis on authoritarian resilience and governance (10–12).

While access to information the regime censors dramatically increases during crisis, note that we do not know the overall impact on public opinion. In the case of the COVID-19 crisis in China, access to blocked platforms facilitates access not only to censored information sensitive to China but also to the Western media, which contains a wide range of negative news about the United States and other democracies. It is generally difficult to infer true levels of support for authoritarian regimes (because of “preference falsification”) (13–15), but we draw out the potential political consequences of increased censorship circumvention in this paper’s Discussion.

Crisis Is a Gateway to Censored Information

In many authoritarian countries, traditional and online media limit access to information (16–19). While this control is imperfect, studies have shown that media control in autocracies has large effects on the opinions of the general public and the resilience of authoritarian regimes (20–26), even though there are moments when it can backfire (9, 27–32). Evidence from China suggests that media control may be effective in part because individuals generally do not expend significant energy to find censored or alternative sources of information.*

While many have studied the impact of information control in normal times in authoritarian regimes, less is known about information seeking during crisis. In democracies, information seeking intensifies during crisis, increasing consumption of mass media. Ball-Rokeach and Defleur (1) describe a model of dependency on the media where audiences are more reliant on mass media during certain time periods, especially when there are high levels of conflict and change in society. These findings are largely consistent with research on emotion in politics, which concludes that political situations that produce anxiety motivate people to seek out information (34). While in normal times information seeking is strongly influenced by preexisting beliefs, several studies have suggested that crisis can cause people to seek out information that might contradict their partisanship or worldview (7, 35), although they may pay disproportionate attention to threatening information (36).

Similar patterns may exist in authoritarian environments. Because the government controls mass media, citizens aware of censorship may not only consume more mass media that is readily available during crises, but also seek to circumvent censorship or seek out alternative sources of information that they may normally not access. For example, during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) crisis in China in 2003, Tai and Sun (37) find that people in China turned to Short Message Service (SMS) and the Internet to gather and corroborate information they received from mass media. Cao (38) shows an increase in censorship evasion and use of Twitter from China during “regime-worsening” events, such as worsening of trade relations between the United States and China and the removal of presidential term limits in the constitution in 2018.

Outside of facilitating access to information about the crisis, evasion of censorship during crisis could also provide information that has long been censored. In particular, a crisis could create spillovers of information, where evasion to find one piece of information facilitates access to a broad range of content. This phenomenon is related to the entertainment-driven “gateway effect” documented in ref. 9, where sudden censorship of an entertainment website (Instagram) motivated censorship evasion and thus facilitated access to unrelated political information. At the same time, crisis is a very different context than is sudden censorship of an entertainment website. Anxiety about the epidemic, perhaps especially when accompanied by boredom during quarantine and lockdown, could lead consumers of information to be more likely to seek out information that has long been censored after they have evaded censorship to better understand the trustworthiness of their government. On the other hand, the crisis itself may be sufficiently distracting to make them less likely to seek out unrelated and long-censored information. Further, crisis-induced spillover effects are more difficult for autocrats to avoid than gateways created through censorship of entertainment websites, which could be reduced by avoiding the initial censorship altogether or implementing less visible censorship. While the overall impact on the autocrat is unknown and could be outweighed by a successful, rapid government response to the crisis, such a gateway would strengthen the ability of consumers to read sources outside of China.

The COVID-19 Crisis in China

On 31 December 2019, officials in Wuhan, China confirmed that a pneumonia-like illness had infected dozens of people. By 7 January 2020, Chinese health officials had identified the disease—a new type of coronavirus called novel coronavirus, later renamed COVID-19. By 10 January, the first death from COVID-19 was reported in China, and soon the first case of COVID-19 was reported outside of China, in Thailand. As of December 2020, COVID-19 has infected over 91,000 people in China with over 4,500 deaths and at least 73.5 million people worldwide with over 1.6 million deaths.†

While initial reports of COVID-19 were delayed by officials in Wuhan (39), Chinese officials took quick steps to contain the virus after it was officially identified and the first deaths were reported. On 23 January 2020, the entire city was placed under quarantine—the government disallowed transportation to and from the city and placed residents of the city on lockdown (40). The next day, similar restrictions were placed on nine other cities in Hubei province (41). While Hubei province and Wuhan were most affected by the outbreak, cities all over China were subject to similar lockdowns. By mid-February, about half of China—780 million people—were living under some sort of travel restrictions (42). Between 10 January and 29 February 2020, 2,169 people in Wuhan died of the virus (43).

The Effect of Crisis on Information Seeking and Censorship Circumvention

We use digital trace data to understand the effect of the COVID-19 crisis on information seeking. Table 1 summarizes the empirical tests conducted in this paper. First, we show that the crisis increased the popularity of virtual private network (VPN) applications, which are necessary to jump the Great Firewall, downloaded on iPhones in China. We also show that the crisis expanded the number of Twitter users in China, which has been blocked by the Great Firewall since 2009. The crisis further increased the number of page views of Chinese language Wikipedia, which has been blocked by the Great Firewall since 2015. We also show that the areas more affected by the crisis—such as Wuhan and Hubei Province—were more likely to see increases in circumvention.

Table 1.

Empirical tests

| Question | Test |

| 1) Do individuals circumvent censorship more during crisis? | VPN ranking; increased use of blocked services; new Twitter users. |

| 2) Do individuals access crisis information? | Wikipedia traffic about current leaders; new mainland China followers for certain account types. |

| 3) Do individuals access noncrisis sensitive information? | Wikipedia traffic to blocked pages; new mainland China followers for activists and foreign political figures. |

| 4) Do these same dynamics occur in democracies and less-censored environments? | Wikipedia page views in German, Italian, Persian, and Russian. |

Next, we show that the increase in circumvention caused by the crisis not only expanded access to information about the crisis, but also expanded access to information that the Chinese government censors. On Twitter, blocked Chinese language news organizations and exiled dissidents disproportionately increased their followings from mainland China users. On Wikipedia, sensitive pages such as those pertaining to Chinese officials, sensitive historical events, and dissidents showed large increases in page views due to the crisis. Finally, Comparison with Other Countries Affected by the Crisis shows that these dynamics do not occur on Italian, German, Persian, or Russian Wikipedia—languages of countries with similar crises but where Wikipedia is uncensored.

Crisis Increased Censorship Circumvention.

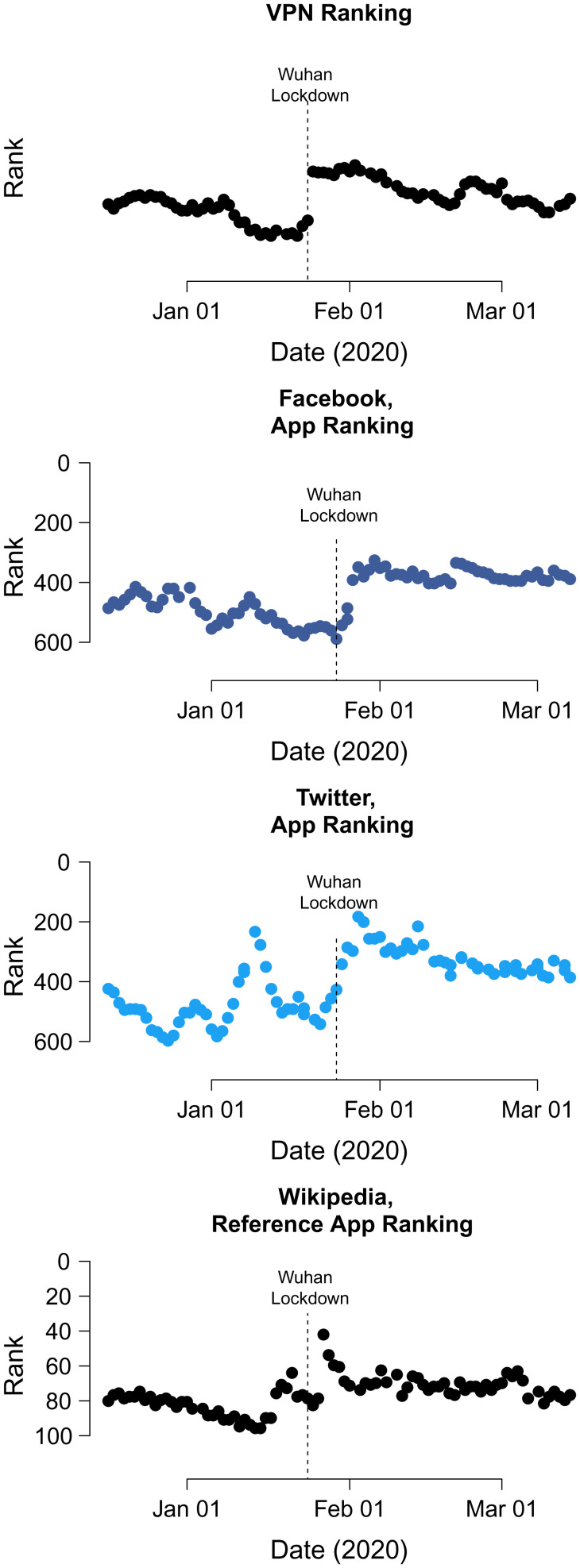

We show that censorship circumvention increased in China as a result of the crisis using data from application analytics firm App Annie, which tracks the ranking of iPhone applications in China. While most VPN applications are blocked from the iPhone Apple Store, we identified one still available on it. Around the time of the Hubei lockdown, its rank popularity increased significantly and maintained that ranking (Fig. 1, Top).‡

Fig. 1.

Download rank of iPhone application in China: Facebook, Twitter, and Wikipedia. Data are from App Annie. Top intentionally omits the name of the VPN app and its precise ranking.

Concurrent with the increase in popularity of the VPN application is a sudden increase in popularity of Facebook, Twitter, and Wikipedia applications, as Fig. 1 shows.§ These increases indicate that those jumping the Firewall as a result of the crisis were engaging in part with long-blocked websites in China—Twitter and Facebook have been blocked since 2009 and Chinese language Wikipedia since 2015.

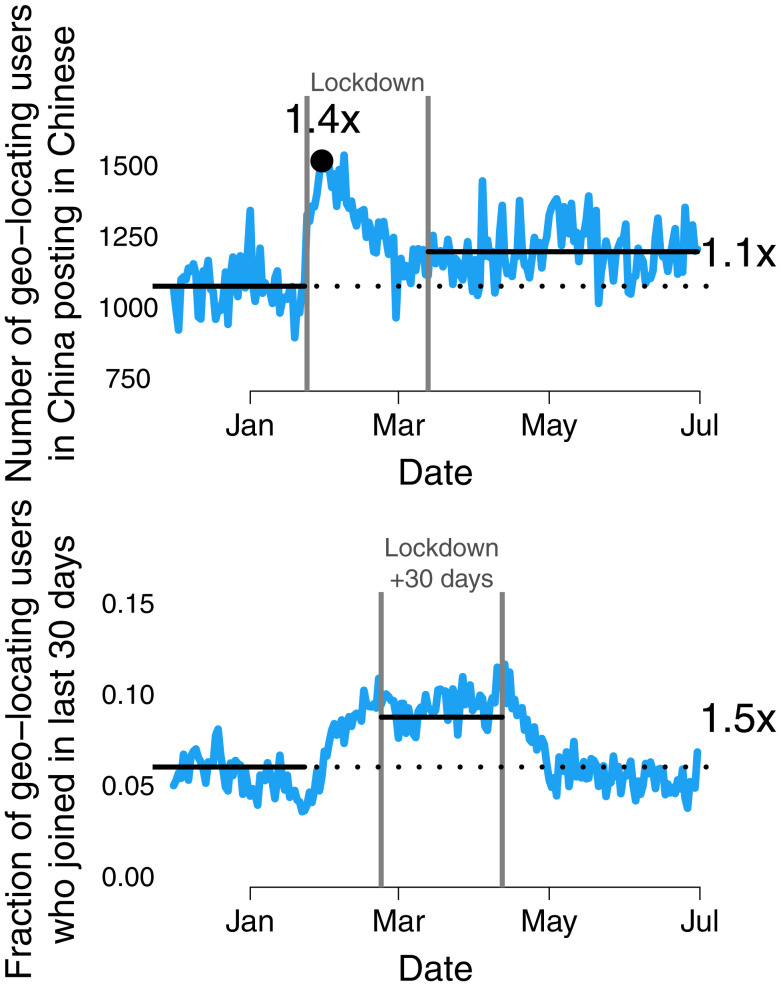

This finding is consistent with data we collected directly from Twitter and Wikipedia. Fig. 2, Top shows the number of geolocating users in China posting to Twitter in Chinese in the time period of interest. Immediately following the lockdown, Chinese language accounts geolocating to China increased 1.4-fold, and postlockdown, 10% more accounts were active from China than before. Fig. 2, Bottom shows that the crisis also coincided with increases of new users, indicating that increases are due to new users and not dormant ones reactivating.¶ We provide a rough, back-of-the-envelope calculation for the absolute size of these effects. If there were 3.2 million Twitter users in China (44) prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the 10% increase in usage applies generally to Twitter users (i.e., not just those geotagging), then 320,000 new users joined Twitter because of the crisis, including users who do not post or post publicly. We assess this estimate in SI Appendix, section 4 using the estimated fraction of posts in Chinese that are geotagged (1.95%) and the total number of unique Twitter users in our sample (47,389 users posting in Chinese and in China).

Fig. 2.

(Top) Number of unique geolocating users in China posting in Chinese. (Bottom) The fraction of active unique users who joined Twitter in the last 30 d. The decline in “new” users after the end of lockdown (Bottom Right) is driven by a decline in new signups after lockdown easing, rather than lockdown users leaving the site (they are no longer considered new after 30 d).

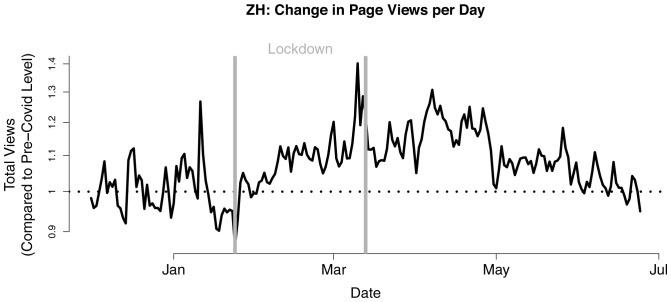

Data from Wikipedia on the number of views of Wikipedia pages by language match the App Annie and Twitter patterns.# We measure the total number of views for Chinese language Wikipedia by day from before the coronavirus crisis to the time of writing. Fig. 3 reveals large and sustained increases in views of Chinese language Wikipedia, beginning at the Wuhan lockdown and continuing above pre-COVID levels through May 2020. Views of all Wikipedia pages in Chinese increased by around 10% during lockdown and by around 15% after the first month of lockdown. This increase persisted long after the crisis subsided. In absolute terms, the total number of page views increases from around 12.8 million views per day in December 2019 to 13.9 million during the lockdown period (24 January through 13 March) and up to 14.7 million views per day from mid-February through the end of April.

Fig. 3.

Views of Wikipedia pages in Chinese. Shown is the ratio of total daily views of Wikipedia pages in Chinese compared to December 2019 views (12.7 million views per day in December 2019). The beginning of the Hubei lockdown and the first relaxation of lockdown in Hubei are indicated in gray.

Increases in Circumvention Occurred throughout China.

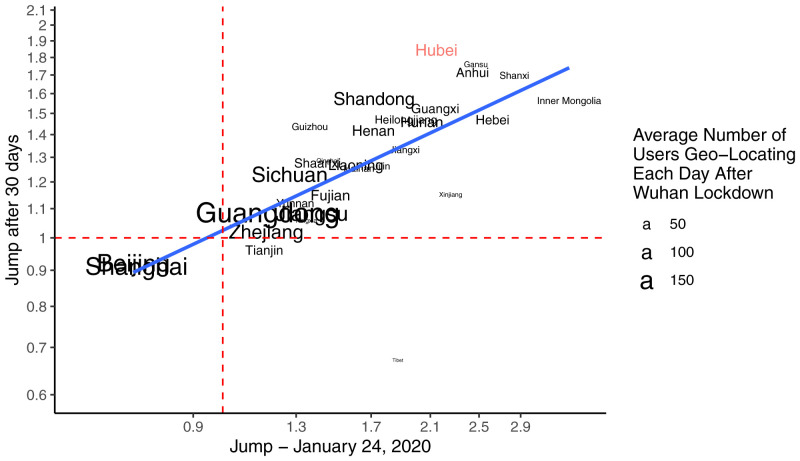

Whereas the data from App Annie and Wikipedia cannot distinguish between circumvention patterns within China, the geolocation in the Twitter data enables the examination of subnational variation. Circumvention occurred in provinces throughout China as a result of the Wuhan lockdown; Hubei, the most impacted province, experienced the most sustained increase in geolocated users.

Fig. 4 measures the initial increase of Twitter volume on 24 January 2020, the day after Wuhan’s lockdown and the start of lockdown in 12 other cities in Hubei, in comparison to the average from 1 December 2020 to 22 January 2020 in each province in China (the x axis). The y axis measures how sustained the increase was—the ratio of Twitter volume 30 d after the quarantine to the baseline before the outbreak. Hubei is in the top right corner of the plot: Twitter volume there doubled in comparison to the previous baseline, and the doubling persisted 30 d after the crisis.ǁ These estimates are drawn from polynomial models fitted to the daily number of users per province—SI Appendix, Fig. A1 displays the modeled lines over the raw data for each province.

Fig. 4.

Increases in geolocated Twitter activity by province (modeled). Shown is the increase in geolocated Twitter users compared to the average number of geolocated Twitter users in a province before the Hubei lockdown. Estimates for 30 d after and day of lockdown are drawn from a five-term polynomial regression on the number of unique geolocated Twitter users per day after the lockdown. These province-by-province polynomials are displayed over the raw data in SI Appendix, Fig. A1.

To further validate that this increase in Twitter usage in China is related to the Wuhan lockdown, we collected real-time human mobility data from Baidu, one of the most popular map service providers in China. The decrease in mobility in 2020 is correlated with the increase in Twitter users across provinces in China, net of a New Year’s effect (SI Appendix, Fig. A3). However, as the crisis spreads, the demobilization effect disappears, while Twitter usage remains elevated. The overall increase in Twitter users across China 2 wk after the lockdown and beyond cannot be explained by further decreases in mobility or New Year seasonality (SI Appendix, Fig. A4). SI Appendix, section 3 presents more detail.

Crisis Provided a Gateway to Censored Political Information.

This subsection examines how the crisis impacted what content Twitter users from mainland China and users of Chinese language Wikipedia were consuming. Both Twitter and Wikipedia facilitate access to a wide range of content, not just information sensitive to the Chinese government. New users of Twitter from China might follow Twitter accounts producing entertainment or even Twitter accounts of Chinese state media and officials, who have become increasingly vocal on the banned platform (45). New users of Wikipedia might seek out only information about the virus and not about politics. If the crisis produced a gateway effect, we should see increases in consumption of sensitive political information unrelated to the crisis.

Types of Twitter accounts mainland China Twitter users started to follow as a result of the crisis.

We use data from Twitter to examine what types of accounts received the largest increases in followers from China due to the crisis. For this purpose, we identify 5,000 accounts that are commonly followed by Twitter users located in China.** Materials and Methods and SI Appendix, section 2 detail how we identified these accounts.

We assigned each of the 5,000 popular accounts into one of six categories: 1) international sources of political information, including international news agencies; 2) Chinese citizen journalists or political commentators, which include nonstate media discussions of politics within China; 3) activists or accounts disseminating information about politics in the United States, Taiwan, or Hong Kong; 4) accounts disseminating pornography; 5) state media and political figures; and 6) entertainment or commercial influencers. Categories 1 to 3 are accounts that might distribute information sensitive to the Chinese government, such as international media blocked by the Great Firewall (e.g., New York Times Chinese and Wall Street Journal Chinese); Chinese citizen journalists and political commentators such as exiled political cartoonist Badiucao and currently detained blogger Yang Hengjun; and political activists such as free speech advocate Wen Yunchao and Wu’er Kaixi, former student leader of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. Accounts in category 4 are pornography, which we consider sensitive because it is generally censored by the Chinese government, but not politically sensitive like categories 1 to 3. Accounts in category 5 include accounts linked to the Chinese government, including the government’s news mouthpieces Xinhua and People’s Daily, as well as the Twitter accounts of Chinese embassies in Pakistan and Japan. Category 6 is also not sensitive, as these accounts mostly do not tweet about politics, but instead are entertainment or commercial accounts or accounts of nonpolitical individuals.

We want to understand how the coronavirus crisis affected trends in follower counts of each of the six categories and, in particular, compare how the crisis affected the followings of categories 1 to 3 to those in categories 5 and 6. We therefore downloaded the profile information of all accounts that began following popular accounts in categories 1 to 3 and 5 and 6 and a random sample of popular accounts from category 4 after 1 November 2019. We then use the location field to identify which of the 38,050,454 followers are from mainland China or Hong Kong (see SI Appendix, section 2 for more details).

Because Twitter returns follower lists in reverse chronological order, we can infer when an account started following another account (46). For the accounts in the six categories, we compare the increase in followers from mainland China to the increase in followers from Hong Kong accounts relative to their December 2019 baselines; we chose Hong Kong because it is part of the People’s Republic of China but is not affected by the Firewall. The ultimate quantity of interest is the ratio of these two increases. If the ratio is greater than one, then the increase in following relationships is more pronounced among mainland Twitter users compared to those from Hong Kong.

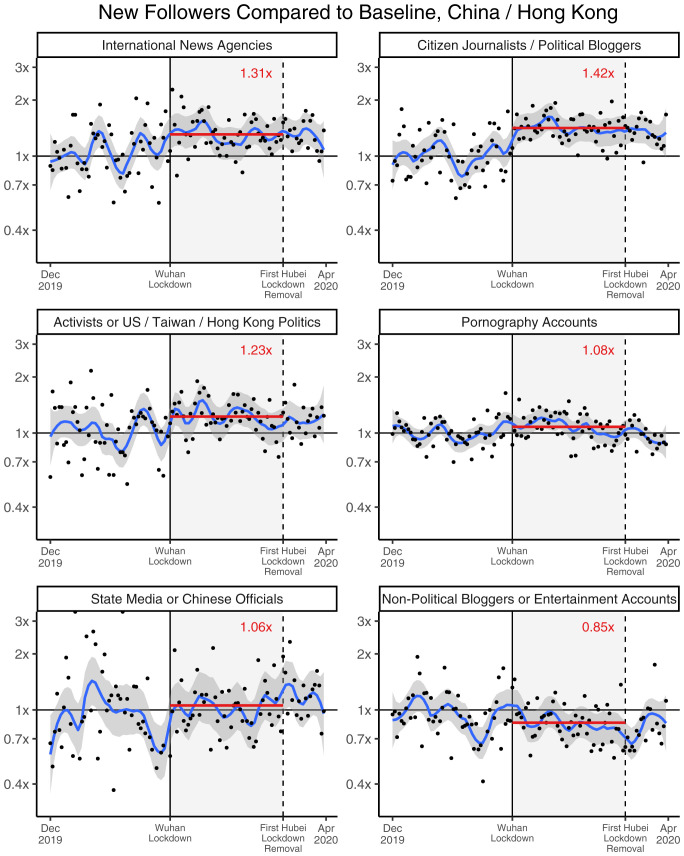

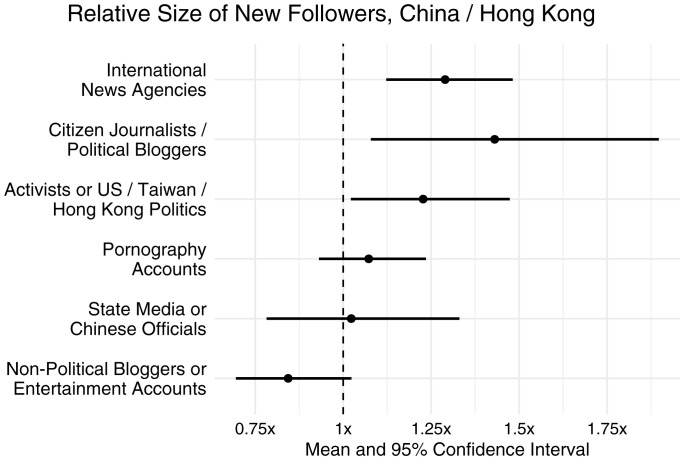

Fig. 5 shows this ratio by category day. Relative to Hong Kong, the crisis in mainland China inspired disproportionate increases in the number of followers of international news agencies, Chinese citizen journalists, and activists (some of whom might otherwise, without exposure on Twitter, be obscure within China, especially ones who have been banned from public discourse for a long time)—users who are considered sensitive and often have long been censored. In comparison, there is only a small increase in mainland followers of Chinese state media and political figures during the lockdown period and a slight decrease for nonpolitical bloggers and entertainers. Fig. 6 reports the regression estimate for the relative ratio of number of new followers (akin to a difference-in-differences design with Hong Kong as control group and December 2019 as pretreatment period). The result is the same.

Fig. 5.

Increases in Twitter followers from China vs. Hong Kong by category. Shown is the gain in followers from mainland China compared to Hong Kong across six types of popular accounts, relative to December 2019 trends. Ratios here approximate the incidence rate ratios estimated in the models for Fig. 6. Each dot represents that category-day’s ratio. The blue lines indicate the moving averages, and the red lines represent the average during Wuhan lockdown. A value greater than 1 means more followers than expected from mainland China than from Hong Kong. Accounts creating sensitive, censored information receive more followers than expected once the Wuhan lockdown starts. Accounts that are not sensitive or censored, such as state media or entertainment, do not see greater than expected increases.

Fig. 6.

Increases in Twitter followers in China vs. Hong Kong by category (regression estimate). Incidence rate ratios shown are from negative binomial regressions of number of new followers on the interaction between indicator variables for “in lockdown period” and “in mainland China,” with December 2019 as control period and Hong Kong as control group.

We then demonstrate that the result does not depend on the choice of comparison group, and the relative increase starts no earlier than the Wuhan lockdown. SI Appendix, Fig. A6 conducts a placebo test by running weekly regressions, showing that the relative increase in followers in China starts precisely during the week of lockdown. In SI Appendix, Figs. A7–A9 show that the same pattern holds with alternative comparison groups such as overseas Chinese in Taiwan and the United States.

Chinese government information operations on Twitter do not explain the results. Of the 28,991 accounts Twitter identified as belonging to a Chinese government information operation,†† none author a tweet in the 1,448,850 streamed geolocated corpus. To confirm this paucity, we then analyze the 14,189,518 tweets Twitter provided from the information operation accounts. Only 0.03% of those tweets are geotagged. Twelve of the 1.45 million tweets mention five information operation accounts. We then download tweets from 1,000 users from China and find zero mentions or retweets of the information operation accounts. We also find that none of these information operation accounts follow any of the popular accounts for which we collected followers.

SI Appendix, section 4 provides effect size estimates. There, we roughly estimate that around 320,000 new users came from China. Further, based on December 2019 follower growth rates, 53,860 excess accounts follow citizen journalists and political bloggers, 52,144 for international news agencies. By the end of the lockdown, citizen journalists and political bloggers benefit from 3.63 times the number of followers they otherwise would have had and activists from 2.97 times. Importantly, 88–90% of the followers from China follow accounts in these categories 1 y later, and these rates are higher than for accounts which start following in the weeks after the end of the Hubei lockdown. In addition, SI Appendix, Fig. A10 shows that new users from China persist in tweeting at the same rates as those from Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Types of Chinese language Wikipedia pages that received the most attention.

To better understand patterns of political views in the Wikipedia data, we leverage existing lists (see Materials and Methods for additional details) to categorize the Chinese language Wikipedia views into three different categories: 1) Wikipedia pages that were selectively blocked by the Great Firewall‡‡ prior to Wikipedia’s move to https (after which all of Chinese language Wikipedia was blocked), 2) pages that describe high-level Chinese officials,§§ and 3) historical leaders of China since Mao Zedong. Whereas we would expect that a crisis in any country should inspire more information seeking about current leaders in category 2, only if crisis created a gateway to historically sensitive information would we expect proportional increases in information seeking about historical leaders in category 3 or information about sensitive events that were selectively blocked by the Great Firewall on Wikipedia prior to 2015 in category 1.

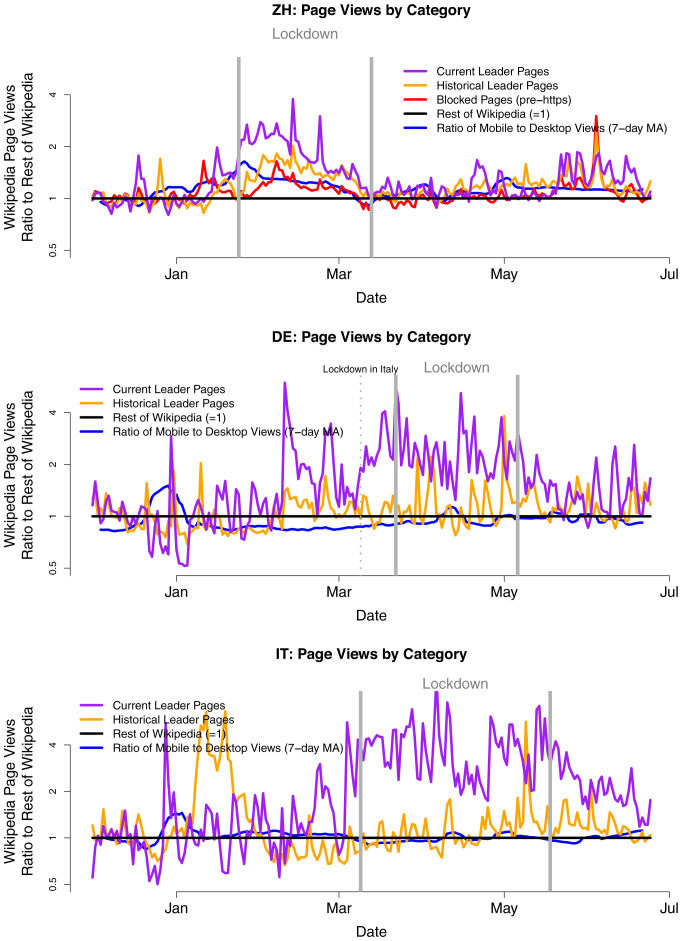

Fig. 7 shows the increase in page views for each of these categories on Chinese Wikipedia relative to the rest of Chinese language Wikipedia. We find that the lockdown not only increased views of current leaders (purple), but also increased views of historical leaders (yellow) and views of pages selectively blocked by the Great Firewall (red). In SI Appendix, Tables A2 and A3 show specific pages disproportionately affected by the increase in views of Wikipedia. While pages related to coronavirus experienced a jump in popularity, other unrelated sensitive pages including the “June 4 Incident,” “Ai Weiwei,” and “New Tang Dynasty Television” (a television broadcaster affiliated with Falun Gong) also experienced an increase in page views.¶¶

Fig. 7.

Views of blocked, current leader, and historical leader Wikipedia pages in Chinese, German, and Italian. Vertical lines indicate the starts and ends of lockdown periods. See SI Appendix, Table A4 for specific dates. ZH, Chinese; DE, German; IT, Italian.

For more detail on this analysis as well as the Wikipedia pages that received the largest absolute and relative increases in traffic, see SI Appendix, section 6.

Comparison with Other Countries Affected by the Crisis.

Since information seeking during crisis is common (1), we investigate Wikipedia data in other languages to explore how other countries were affected by the crisis. We show that the gateway effect of crisis on historically sensitive information is unique to the currently censored webpages in China. For comparison, we focus on Iran, another authoritarian country affected by COVID-19 that previously censored Wikipedia (but does not any longer), and Russia, an authoritarian country that does not censor Wikipedia—for Iran, like China, we know which Wikipedia pages were previously censored (47). We also show data from democracies without censorship affected early on by the COVID-19 crisis, Italy and Germany.##

To make the comparison, we use lists of current leaders from these countries (based on office lists in the CIA World Factbook) (Materials and Methods) and create lists of historical leaders using de facto country leaders since World War II (see SI Appendix, Table A4 for a list of these titles and offices). All of these countries were affected by the crisis in late February or early March, and Italy imposed relatively stringent lockdowns. Therefore, we expect increases in information seeking for current leaders, as citizens begin to pay more attention to current politics as the crisis hits. However, none of these countries block Wikipedia. Information seeking about the current crisis therefore should not act as a gateway to information about historical events or controversies, as these pages are always available to the public.

Table 2 shows these results. While overall Wikipedia views and page views of current leaders increase in three of four comparison languages, only for Chinese language Wikipedia do historical leaders increase disproportionately and consistently throughout the whole time period. That is, we see an overall effect on information seeking throughout the world, including for historical leaders; for Chinese language Wikipedia, we see larger increases for historical leaders compared to Wikipedia page views in general. The small increases in historical political leader page views in German and Italian did not correspond with the start of the COVID-19 crisis or their respective lockdowns (Fig. 7).

Table 2.

During the lockdown period, Wikipedia views in Chinese increased relative to overall views for politically sensitive Wikipedia pages and political leader pages, as well as for historical political leaders

| Change Language | Overall | Blocked, pre-https relative to overall | Leaders | Historical leaders |

| Chinese | 1.09 | 1.15 | 1.86 | 1.42 |

| (1.05 to 1.12) | (1.09 to 1.22) | (1.67 to 2.07) | (1.32 to 1.52) | |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Persian | 1.42 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.82 |

| (1.37 to 1.46) | (0.79 to 0.89) | (0.80 to 1.05) | (0.75 to 0.90) | |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.20 | <0.001 | |

| Russian | 1.23 | 1.73 | 0.90 | |

| (1.18 to 1.28) | (1.48 to 2.02) | (0.82 to 0.99) | ||

| <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 | ||

| German | 1.16 | 2.36 | 1.21 | |

| (1.12 to 1.20) | (2.02 to 2.76) | (1.05 to 1.40) | ||

| <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 | ||

| Italian | 1.47 | 3.29 | 1.17 | |

| (1.40 to 1.53) | (2.72 to 4.00) | (1.02 to 1.34) | ||

| <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 |

Incidence rate ratios shown are from a negative binomial regression estimating the daily number of views within a category in the lockdown period compared to December 2019 relative to the number of views across the rest of Wikipedia compared to December 2019 (using the same difference-in-difference specification as the Twitter follower analysis). Observations are the total views per category by day. The 95% confidence intervals are shown in parentheses, and P values are shown in the third row for each language. See SI Appendix for over-time ratios by day for all comparison languages (SI Appendix, Fig. A11) and for the dates of the lockdowns used (SI Appendix, Table A4). German and Italian pages of historical leaders (shown in orange in Fig. 7) show several large and short-lived spikes in views not clearly related to those countries’ lockdowns. In SI Appendix, Figs. A12–A15 replicate these results for much larger sets of Wikipedia pages, including Russian language pages related to opposition leaders and movements (which did not see broad increases in views).

Further, we do not see increased attention to pages previously blocked in Iran (47) during the crisis—Wikipedia pages that can now be accessed without restriction in Iran.

In SI Appendix, section 6.2, we replicate these results for much larger sets of 1) historical leaders and 2) “politically sensitive” pages (pages related to the pre-https blocked pages in Iran and China and political opposition pages in Russia). We expand these sets of pages using Wikipedia2vec (48) and find that very broad information seeking about historical leaders and politically sensitive topics occurred only for Chinese language Wikipedia.

Discussion

Crisis in highly censored environments creates widespread spillovers in exposures to sensitive, censored information, including information not directly related to the crisis. Like in democracies, consumers of information in autocracies seek out information and depend on the media during crisis. However, in highly censored environments, increased information seeking also incentivizes censorship circumvention. This new ability to evade censorship allows users to discover a wider variety of information than they may have initially sought, and users could also be particularly motivated to seek out accumulated, hidden information during a crisis. Our results suggest that informational spillovers produced by censorship evasion are a result of the structure of censorship and that they occur beyond government-induced backfire from sudden censorship of popular entertainment websites (9).

Public exposure to censored information during crisis is almost certainly not the intention of any regime with widespread censorship. However, the effect of this crisis-induced gateway to censored information on public opinion is unknown. In the case studied in this paper, surveys in China show increased support for the CCP over the course of the pandemic (and over the same time as large declines in favorability toward the United States) (49), even though we show that this increase in support occurs in conjunction with increased access to censored information. These findings could reflect favorable reactions to the government’s pandemic policy response that may have overwhelmed negative impacts of access to censored information (50). Or the increase in support at a time of greater evasion of censorship could lend support to previous findings that access to Western news sources can counterintuitively increase support for the regime (51, 52). Studying the impact of evasion during the crisis on public opinion is left to future research. However, we include in SI Appendix, section 7 an exploratory analysis of the content posted by the popular accounts followed by our sample. While we see quite negative coverage of China on these accounts and coverage of sensitive topics such as human rights, the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, and protests in Hong Kong, we also find that coverage of the United States by international news agencies was much more negative or neutral than positive, and the United States could have served as a favorable comparison for China and the Chinese government’s handling of the pandemic.

While evaluations of responses to an ongoing crisis and comparisons to other governments’ responses to the same crisis may have benefited government officials in China in this particular circumstance (50), beyond these evaluations, increased access to historical and long-censored information, as documented here, has the potential to dampen positive or compound negative changes in trust and may also contribute to easier access to uncensored information about a government in the future. Natural disasters, including epidemics, tend to alter trust in government officials. When a policy response is perceived as efficacious, support for the level of government perceived to have directed the response increases (12, 53). On the other hand, neglectful responses can induce subsequent protest participation (11). In China, the average effect of natural disasters from 2007 to 2011 was to decrease political trust, and internet users have decreased baseline levels of political trust (53, 54). At the same time, political surveys in China suffer from preference falsification (13–15), complicating our efforts to understand the political consequences of these events.

While the results here do not link the COVID-19 crisis gateway effect to the political fortunes of the Chinese government, they do suggest that a country with a highly censored environment sees distinctive and wide-ranging increases in information access during crisis. While in normal times censorship can be highly effective and widely tolerated, crisis heightens incentives to circumvent censorship, and regimes cannot rely on the same limits on information access during crisis, even for topics long controlled.

Materials and Methods

Application Download Rank Data.

Download rank data for Facebook, Twitter, Wikipedia, and the VPN app come from application analytics firm App Annie (https://www.appannie.com), which tracks the popularity of iPhone application downloads in China. While most VPN applications are blocked from the iPhone Apple Store (and there are other means of obtaining VPNs), we identified one still available on it. VPN download rank shown in the text is for that VPN application. These data contain the ranking of an application—for Wikipedia, its rank within the Reference App category—rather than the number of downloads. To protect the VPN application and its users, we do not disclose its name or the exact ranking.

Twitter Data.

For the Twitter analyses, we collected 1,448,850 tweets (101,553 accounts) from mainland China from 1 December 2019 until 30 June 2020. These tweets were identified using Twitter’s POST statuses/filter endpoint. Our analyses are limited to the 367,875 that were posted in Chinese (47,389 accounts that posted in Chinese, 43,114 that had names or descriptions in Chinese).

The Twitter follower analysis examines accounts that Twitter users from China commonly follow. To find those accounts, we randomly sampled 5,000 users geolocated to China. For each of these users, we gathered the entire list of whom they follow, their Twitter “friends.” From these 1,818,159 friends, we extracted the 5,000 most common accounts. We also selected only accounts that were Chinese language accounts or had Chinese characters in their name or description field to ensure that we were studying relevant accounts: those disseminating information easily accessible to most Chinese users. SI Appendix, section 2 provides more detail.

We downloaded the profile information of all accounts that began following these popular accounts after 1 November 2019. Because Twitter returns follower lists in reverse chronological order, we can infer when an account started following another account (46). We then use the location field to identify which of these 38,050,454 followers are from mainland China or Hong Kong (see SI Appendix, section 2 for more details). We downloaded all new followers of nonpornography accounts and all new followers of a random selection of 200 pornography accounts (the majority of the accounts were pornography). This sampling allows us to estimate the impact of the coronavirus on pornography while decreasing our requests to the Twitter Application Programming Interface.

Mobility Data.

Human mobility data are publicly available from Baidu Qianxi (https://qianxi.baidu.com/2020/), which tracks real-time movement of mobile devices and is used in studies of human mobility and COVID-19 containment measures (55). Our robustness checks use data across China during the Lunar New Year period in both 2020 and 2019. We extracted the data from the webpage, including the daily within-city movement index (an indexed measure of commuter population relative to the population of the city) as well as daily moving-out index (an indexed measure based on the volume of population moving out of the province relative to the total volume of migrating population on that day across all provinces in China). See SI Appendix, section 3 for more details.

Wikipedia Data.

Data on the number of Wikipedia page views are publicly available at https://dumps.wikimedia.org/other/pagecounts-ez/merged/. To better understand patterns of political views in the Wikipedia data, we use existing lists to categorize the Chinese language Wikipedia views into three different categories: 1) Wikipedia pages that were selectively blocked by the Great Firewall (https://www.greatfire.org/ maintains a list of websites censored by the Great Firewall) prior to Wikipedia’s move to https, after which all of Wikipedia was blocked; 2) pages about high-level Chinese officials (using offices listed in the CIA World Factbook, https://web.archive.org/web/20201016160945/ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/world-leaders-1/CH.html, excluding Hong Kong and Macau as well as the Ambassador to the United States); and 3) historical “paramount” leaders of China since Mao Zedong.

In comparing multiple languages and countries, we use the same offices listed in the CIA World Factbook to create lists of current leaders from Iran, Russia, Italy, and Germany (for office holders as of February 2020) and create lists of historical leaders using de facto country leaders since World War II. See SI Appendix, Table A4 for a list of these titles and offices, as well as the lockdown start and end dates used in the Wikipedia page view models displayed in Table 2. The list of Wikipedia pages blocked in Iran was published by Nazeri and Anderson (47).

In SI Appendix, section 6.2, we replicate the Wikipedia page view results for much larger sets of 1) historical leaders and 2) politically sensitive pages (pages related to the pre-https blocked pages in Iran and China and political opposition pages in Russia). We expand these sets of pages using Wikipedia2vec (48).

Models.

Incidence rate ratios for the follower analyses and the Wikipedia page view analyses are from negative binomial regressions. In the follower analysis, this models the number of new followers per day, with a separate model for each account category. Independent variables are “in lockdown period” and “in mainland China,” and the effect of interest is the interaction between these indicator variables (i.e., a difference in difference), with December 2019 as control period and Hong Kong as control group. The Wikipedia page view analyses use the same specification, reporting the coefficient for “in lockdown period” and “in page set” (current leader, historical leader, previously blocked) relative to December 2019 and relative to page views for the rest of Wikipedia. Observations are the total views per category by day. Figures displaying (log-scale) ratios of followers/Wikipedia page views approximate coefficients from these negative binomial regressions. Negative binomial regressions were estimated using the MASS library in R.

Increases in geolocated Twitter activity (unique users) by day and by province were modeled using a five-term polynomial regression (by day) for time trends after the Hubei lockdown and a mean without any time trend prior to lockdown (see SI Appendix, Fig. A1 for a province-by-province visualization of this model). The points in Fig. 2 are predicted values by province for the first day of lockdown and day 30 of lockdown.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Qitong Cao, Lei Guang, Ruixue Jia, Susan Shirk, and Yiqing Xu in addition to participants at workshops at New York University, the University of Chicago, University of Southern California, and University of California, San Diego for helpful feedback. This work was partially supported by the National Science Foundation Grant 1738411.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2102818119/-/DCSupplemental.

*Stockmann (24) provides evidence that consumers of newspapers in China are unlikely to go out of their way to seek out alternative information sources. Chen and Yang (33) provided censorship circumvention software to college students in China, but found that students chose not to evade the Firewall unless they were incentivized monetarily. Roberts (26) provides survey evidence that very few people choose to circumvent the Great Firewall because they are unaware that the Firewall exists or find evading it difficult and bothersome.

†Source: New York Times, 15 December 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/world/coronavirus-maps.html.

‡To protect the application and its users, we are not disclosing its name or the exact ranking.

§Note that increase in popularity is not comparable across applications because popularity is measured in terms of ranks. More highly ranked applications (like Facebook and Twitter) may need many more downloads to achieve a more popular ranking.

¶SI Appendix, section 2 provides more detail, and SI Appendix, Fig. A1 shows trends per province.

#Wikipedia page view data are publicly available: https://dumps.wikimedia.org/other/pagecounts-ez/merged/. Note that these data do not track where users are from geographically; we use language as an imperfect proxy for geography.

ǁWhile almost all provinces experience a sustained increase in Twitter volume, Beijing and Shanghai have an overall decrease in Twitter volume after the outbreak. We suspect many Twitter users in Beijing and Shanghai left those cities during the outbreak, which is corroborated by the Baidu mobility data we detail in SI Appendix, section 3.

**We note that follower behavior is a useful window into user behavior and has advantages over other metrics in this context like the content of the new users’ tweets. First, merely following accounts is likely a less risky behavior than publicly posting content about politics, especially that related to China. That is, we expect users to self-censor their posts but not (to the same extent) whom they only follow. Second, tweet activity is right skewed in our data, which is common in social media data. The median account in the stream tweets twice, and the top 1% of active users author 40.3% of tweets. Analyzing tweets would therefore create a less complete analysis of user behavior than analyzing following relationships.

††In June 2020 and September 2019, Twitter released datasets containing 28,991 accounts it identified as being part of pro-China information operation campaigns (https://transparency.twitter.com/en/reports/information-operations.html). Twitter granted us access to the unhashed version of the data they do not publicly release, meaning we had the information operation campaigns’ accounts’ actual screen names and user identification numbers.

‡‡Using data from https://www.greatfire.org/.

§§These lists are based on offices in the CIA World Facebook. We use this list for ease of comparisons with other countries and remove the Ambassador to the United States from each list. China’s list is available here (and there are links to leaders of other countries on the same page): https://web.archive.org/web/20201016160945/ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/world-leaders-1/CH.html, excluding Hong Kong and Macau.

¶¶The June 2020 increase in China is due to the anniversary of Tiananmen Square protests. Our claim is not that only the COVID-19 crisis causes increases in views of sensitive content. That the same behavior is observed around another crisis event supports this paper’s argument.

##Like China, citizens in each of these countries speak languages relatively specific to their country, and therefore we expect most of the page views of Italian, German, Persian, and Russian Wikipedia to originate in Italy, Germany, Iran, and Russia, respectively.

Data Availability

Replication materials, R scripts, and data files are posted on Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/W2NSLS) (56).

References

- 1.Ball-Rokeach S. J., DeFleur M. L., A dependency model of mass-media effects. Communic. Res. 3, 3–21 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loveless M., Media dependency: Mass media as sources of information in the democratizing countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Democratization 15, 162–183 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirschburg P. L., Dillman D. A., Ball-Rokeach S. J., “Media system dependency theory: Responses to the eruption of Mount St. Helens” in Media, Audience, Social Structure, Alexander J., Ball-Rokeach S. J., Cantor M. G., Eds., Sage; (1986), pp. 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Althaus S. L., American news consumption during times of national crisis. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 35, 517–521 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Y. C., Jung J. Y., Cohen E. L., Ball-Rokeach S. J., Internet connectedness before and after September 11 2001. New Media Soc. 6, 611–631 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bar-Ilan J., Echermane A., The anthrax scare and the web: A content analysis of web pages linking to resources on anthrax. Scientometrics 63, 443–462 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus G. E., MacKuen M. B., Anxiety, enthusiasm, and the vote: The emotional underpinnings of learning and involvement during presidential campaigns. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 87, 672–685 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribeiro M. H., et al., Sudden attention shifts on Wikipedia following COVID-19 mobility restrictions. arXiv [Preprint] (2020). https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.08505 (Accessed 5 May 2021).

- 9.Hobbs W. R., Roberts M. E., How sudden censorship can increase access to information. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 112, 621–636 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn M. E., The death toll from natural disasters: The role of income, geography, and institutions. Rev. Econ. Stat. 87, 271–284 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flores A. Q., Smith A., Leader survival and natural disasters. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 43, 821–843 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazarev E., Sobolev A., Soboleva I. V., Sokolov B., Trial by fire: A natural disaster’s impact on support for the authorities in rural Russia. World Polit. 66, 641–668 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang J., Yang D. L., Lying or believing? Measuring preference falsification from a political purge in China. Comp. Polit. Stud. 49, 600–634 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen X., Truex R., In search of self-censorship. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 1672–1684 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson D., Tannenberg M., Self-censorship of regime support in authoritarian states: Evidence from list experiments in China. Res. Polit. 6, 2053168019856449 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morozov E., The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom (PublicAffairs, New York, NY, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacKinnon R., Consent of the Networked: The Worldwide Struggle For Internet Freedom (Basic Books, New York, NY, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deibert R., Palfrey J., Rohozinski R., Zittrain J., Access Contested: Security, Identity, and Resistance in Asian Cyberspace (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanovich S., Stukal D., Tucker J. A., Turning the virtual tables: Government strategies for addressing online opposition with an application to Russia. Comp. Polit. 50, 435–482 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stockmann D., Gallagher M. E., Remote control: How the media sustain authoritarian rule in China. Comp. Polit. Stud. 44, 436–467 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enikolopov R., Petrova M., Zhuravskaya E., Media and political persuasion: Evidence from Russia. Am. Econ. Rev. 101, 3253–3285 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adena M., Enikolopov R., Petrova M., Santarosa V., Zhuravskaya E., Radio and the rise of the Nazis in prewar Germany. Q. J. Econ. 130, 1885–1939 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanagizawa-Drott D., Propaganda and conflict: Evidence from the Rwandan genocide. Q. J. Econ. 129, 1947–1994 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stockmann D., Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang H., Propaganda as signaling. Comp. Polit. 47, 419–444 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts M. E., Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China’s Great Firewall (Princeton University Press, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan J., Siegel A. A., How Saudi crackdowns fail to silence online dissent. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 114, 109–125 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jansen S. C., Martin B., Making censorship backfire. Counterpoise 7, 5–15 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nabi Z., Censorship is futile. arXiv [Preprint] (2014) https://arxiv.org/abs/1411.0225 (Accessed 20 September 2020).

- 30.Hassanpour N., Media disruption and revolutionary unrest: Evidence from Mubarak’s quasi-experiment. Polit. Commun. 31, 1–24 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glässel C., Paula K., Sometimes less is more: Censorship, news falsification, and disapproval in 1989 East Germany. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 61, 682–698 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boxell L., Steinert-Threlkeld Z., Taxing dissent: The impact of a social media tax in Uganda. Working Paper (2019) https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.04107 (Accessed 9 September 2019).

- 33.Chen Y., Yang D. Y., The impact of media censorship: 1984 or brave new world? Am. Econ. Rev. 109, 2294–2332 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcus G. E., Neuman W. R., MacKuen M., Affective Intelligence and Political Judgment (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacKuen M., Wolak J., Keele L., Marcus G. E., Civic engagements: Resolute partisanship or reflective deliberation. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 54, 440–458 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albertson B., Gadarian S. K., Anxious Politics: Democratic Citizenship in a Threatening World (Cambridge University Press, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tai Z., Sun T., Media dependencies in a changing media environment: The case of the 2003 SARS epidemic in China. New Media Soc. 9, 987–1009 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao Q., The limitations of internet censorship for authoritarian information control:evidence from China. Working Paper (2020) https://bit.ly/3eQlUTk (Accessed 26 February 26).

- 39.Buckley C., Myers S. L., As new coronavirus spread, China’s old habits delayed fight. NY Times, 2 February 2020, Section A, p. 1.

- 40.Qin A., Wang V., Wuhan, center of coronavirus outbreak, is being cut off by Chinese authorities. NY Times, 23 January 2020, Section A, p. 1.

- 41.Griffiths J., John T., George S., Unprecedented Lockdown on 10 Cities and 30 Million People (CNN, 2020) https://www.cnn.com/asia/live-news/coronavirus-outbreak-hnk-intl-01-24-20/h_2587b2ec049c50eb87e75f321f40d2b4 (Accessed 24 January 2020).

- 42.Griffiths J., Woodyatt A., 80 Million People in China Are Living Under Travel Restrictions due to the Coronavirus Outbreak (CNN, 2020) https://www.cnn.com/2020/02/16/asia/coronavirus-covid-19-death-toll-update-intl-hnk/index.html (Accessed 16 February 2020).

- 43.Belluck P., Coronavirus death rate in Wuhan is lower than previously thought, study finds. NY Times, 19 March 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/health/wuhan-coronavirus-deaths.html.

- 44.Mozur P., Twitter users in China face detention and threats in new Beijing crackdown. NY Times, 11 January 2019, Section A, p. 1.

- 45.Zhou L., Chinese officials have finally discovered Twitter. What could possibly go wrong? South China Morning Post, 4 August 2019. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3021310/chinese-officials-have-finally-discovered-twitter-what-could.

- 46.Steinert-Threlkeld Z. C., Longitudinal network centrality using incomplete data. Polit. Anal. 25, 308–328 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nazeri N., Anderson C., Citation Filtered: Iran’s Censorship of Wikipedia (Iran Media Program, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamada I., et al., Wikipedia2Vec: An efficient toolkit for learning and visualizing the embeddings of words and entities from Wikipedia. in Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP, 2020), pp. 23–30.

- 49.Guang L., Roberts M., Xu Y., Zhao J., China Data Lab Blogpost (2020). http://chinadatalab.ucsd.edu/viz-blog/pandemic-sees-increase-in-chinese-support-for-regime-decrease-in-views-towards-us/ (Accessed 10 August 2021).

- 50.Stasavage D., Democracy, autocracy, and emergency threats: Lessons for COVID-19 from the last thousand years. Int. Organ. 74, 1–17 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whyte M., Myth of the Social Volcano: Perceptions of Inequality and Distributive Injustice in Contemporary China (Stanford University Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang H., Yeh Y. Y., Information from abroad: Foreign media, selective exposure and political support in China. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 611–636 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 53.You Y., Huang Y., Zhuang Y., Natural disaster and political trust: A natural experiment study of the impact of the Wenchuan earthquake. Chin. J. Sociol. 6, 140–165 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee J., The social impact of natural hazards: A multi-level analysis of disasters and forms of trust in mainland China. Disasters 45, 158–179 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kraemer M. U. G., et al.; Open COVID-19 Data Working Group, The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science 368, 493–497 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang K.-C., Hobbs W. R., Roberts M. E., Steinert-Threlkeld Z., Replication data for: COVID-19 increased censorship circumvention and access to sensitive topics in China. Harvard Dataverse. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/W2NSLS. Deposited 1 December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials, R scripts, and data files are posted on Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/W2NSLS) (56).