Abstract

Introduction

To compare inpatient treated patients with idiopathic (ISSNHL) and non-idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (NISSNHL) regarding frequency, hearing loss, treatment and outcome.

Methods

All 574 inpatient patients (51% male, median age: 60 years) with ISSNHL and NISSNHL, who were treated in federal state Thuringia in 2011 and 2012, were included retrospectively. Univariate and multivariate statistical analyses were performed.

Results

ISSNHL was diagnosed in 490 patients (85%), NISSNHL in 84 patients (15%). 49% of these cases had hearing loss due to acute otitis media, 37% through varicella-zoster infection or Lyme disease, 10% through Menière disease and 7% due to other reasons. Patients with ISSNHL and NISSNHL showed no difference between age, gender, side of hearing loss, presence of tinnitus or vertigo and their comorbidities. 45% of patients with ISSNHL and 62% with NISSNHL had an outpatient treatment prior to inpatient treatment (p < 0.001). The mean interval between onset of hearing loss to inpatient treatment was shorter in ISSNHL (7.7 days) than in NISSNHL (8.9 days; p = 0.02). The initial hearing loss of the three most affected frequencies in pure-tone average (3PTAmax) scaled 72.9 dBHL ± 31.3 dBHL in ISSNHL and 67.4 dBHL ± 30.5 dBHL in NISSNHL. In the case of acute otitis media, 3PTAmax (59.7 dBHL ± 24.6 dBHL) was lower than in the case of varicella-zoster infection or Lyme disease (80.11 dBHL ± 34.19 dBHL; p = 0.015). Mean absolute hearing gain (Δ3PTAmaxabs) was 8.1 dB ± 18.8 dB in patients with ISSNHL, and not different in NISSNHL patients with 10.2 dB ± 17.6 dB. A Δ3PTAmaxabs ≥ 10 dB was reached in 34.3% of the patients with ISSNHL and to a significantly higher rate of 48.8% in NISSNHL patients (p = 0.011).

Conclusions

ISSNHL and NISSNHL show no relevant baseline differences. ISSNHL tends to have a higher initial hearing loss. NISSHNL shows a better outcome than ISSNHL.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00405-021-06691-y.

Keywords: Idiopathic hearing loss, Non-idiopathic hearing loss, Acute otitis media, Zoster oticus

Introduction

So far, many studies have analyzed epidemiological data for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (ISSNHL) [1, 2]. In a previous study on the ISSNHL, left side, non-declining audiogram type and no previous outpatient treatment as independent prognostic factors for a better recovery could be found [3]. Profound hearing loss, hearing loss in older patients, delayed treatment and arterial hypertension were negative prognostic factors in another study [4]. In sum, there are high reported recovery rates up to 32% to 65% [5, 6]. There are some uncertainties due to therapy strategies but the possible therapy strategies are discussed extensively in therapy recommendations [7]. Systemic glucocorticoid, rheological therapy, local glucocorticoid therapy or even a wait-and-see strategy is currently recommended [8].

In contrast, not much is known on the outcome of non-idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (NISSNHL), because in all studies analyzing hearing loss and recovery these patients are excluded [9, 10]. The aim of this work is therefore to define whether an underlying cause of hearing loss in patients with NISSNHL is associated with a different prognosis for hearing gain than is the case with ISSNHL.

In the federal state of Thuringia, there are eight hospitals with departments for ears-nose-throat (ENT) medicine. These have formed a network for the scientific evaluation of ENT diseases [11, 12]. Recently, we have published data on all patients who were hospitalized in Thuringia in 2011 and 2012 for treatment of ISSNHL [3, 11, 12]. Here, we compare now the results of these patients with ISSNHL to the patients treated for NISSNHL in the same time period.

Methods

Study design and patients

We performed a retrospective analysis in all eight ENT departments of the federal state Thuringia. All patients who were hospitalized in 2011 and 2012 due to acute hearing loss with the ICD codes (International Classification of Diseases) H91.0, H91.1, H91.2, H91.3, H91.8 and H91.9 were included in the study. A positive ethical vote for the evaluation of the underlying data was obtained (No. 2726-12/09, 4755-0416). A total of 723 patients with the above-mentioned diagnoses were treated as inpatient patients and were included in the primary dataset. It made no difference whether the patients had comorbidities or had already received prior outpatient treatment. 58 patients were initially excluded from the evaluation due to missing data sets (e.g. no initial hearing investigation) and 91 patients were excluded due to a lack of initial hearing loss, inpatient treatment due to middle ear surgery or cochlear implantation or lack of follow-up hearing examinations. Of the remaining 574 patients, 490 had an idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (ISSNHL) while the remaining 84 patients had a disease underlying the hearing loss (Menière disease, acute otitis media, Lyme disease, varicella-zoster infection) and were classified as NISSNHL. All 574 patients, ISSNHL as well as NISSNHL, were examined in the present study (Supplemental Digital Content 1).

The follow-up was recorded and evaluated until August 2013. Patient data such as age and gender, clinical and functional examination, medical and surgical treatment were recorded and the treatment of hearing loss in the case of ISSNHL compared to NISSNHL was evaluated.

The extent of the initial hearing loss was described using the pure-tone average (PTA) in decibels hearing level (dB HL). The average hearing loss of the three most affected frequencies (3PTAmax), 10 frequencies (10PTA: 0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 1.5; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 9 frequencies (9PTA: 0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 4frequencies (4PTA: 0.5; 1; 2; 4 kHz), low- (LF3PTA: 0.125; 0.5; 1 kHz), middle- (MF3PTA: 2; 3; 4 kHz), and high frequency (HF2PTA: 6; 8 kHz) hearing loss were calculated [3, 13, 14]. Hearing losses that were not technically measurable and deafness were considered as hearing loss of 120 dB. According to Plontke et al., the outcome was calculated as an absolute hearing improvement before therapy compared to the follow-up (ΔPTAabs = PTApre minus PTApost in dB) [13]. Furthermore, relative (rel) hearing improvement was calculated as ΔPTArel = 100*(PTApre minus PTApost)/PTApre and relative hearing improvement compared to the contralateral ear (contral) ΔPTArelcontral = 100* (PTApre minus PTApost)/(PTApre minus PTA contral). ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB, ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB, ΔPTArel ≥ 50% and ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% in a dichotomous distribution (yes / no) were considered as criterions for a successful improvement [13]. Kanazaki et al. defines no recovery as < 10 dB hearing improvement relative to the initial hearing loss. Each hearing gain of ≥ 10 dB is defined as at least partial hearing gain, which is why an absolute hearing gain of ≥ 10 dB was considered as a criterion for success in the univariate analysis in this study [15]. As the endpoint of the univariate analyses, we used the 3PTAmax as it was done before [3, 14, 16].

The epidemiological statistics were calculated on the basis of the annual average population of Thuringia from 2011 and 2012, which are published in the online database of the statistical office of the federal state of Thuringia (www.tls.thueringen.de).

The patients affected by ISSNHL were treated according to the German guidelines for the treatment of sudden hearing loss: All patients received intravenous prednisolone therapy. Prednisolone was administered in a dose of 250 mg/d (range of 100–500 mg/d) [7, 8]. The dose was then reduced over 7 to 10 days. If there was no improvement in hearing within 3 days under prednisolone therapy and the hearing was below 80 dB in 4PTA, tympanoscopy with round window membrane sealing was performed. If the hearing threshold 4PTA after 3 days of prednisolone treatment was still below 40 dB salvage intratympanic dexamethasone instillation was performed [7]. There was no standardized procedure for performing dexamethasone instillation. In addition to the specific treatment of the cause of their hearing loss, patients with NISSNHL received also a therapy with prednisolone according to the above-mentioned scheme. Patients with varicella zoster infection were treated with acyclovir. Patients with acute otitis media received antibiotic therapy and paracentesis. Patients with Lyme disease received doxycycline or ceftriaxone. Patients with Menière disease were treated with glucocorticoids and antivertiginous therapy.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise noted, data were presented with mean values ± standard deviation (SD). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, version 24.0.0.0. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney-U-test for independent metric data was applied to compare different subgroups of patients. The Chi-square test was applied for independent nominal data. The non-parametric Wilcoxon test for dependent metric data was applied to analyze differences between initial hearing loss and final hearing loss on the affected ear at the end of the follow-up. A multivariate binary logistic regression was performed including the significant associations. Nominal p-values of two-tailed tests are reported. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Subjects and treatment

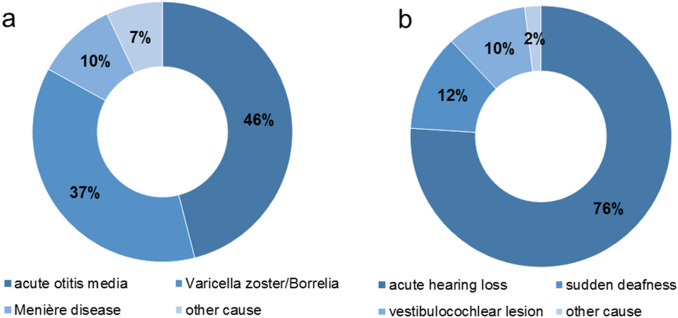

In 2011 and 2012, a total of 574 patients who were hospitalized in Thuringia for acute hearing loss were included in this study. The mean age was 57.2 ± 16 years. 51% of the patients were male, 49% female. 490 patients had ISSNHL (51% male, 49% female, mean age 55.7 years ± 15.9 years). 12% of the patients had an acute deafness and 2% had a combined vestibulocochlear lesion (Fig. 1a). In the other 84 patients, i.e. in 14.6% of cases, an underlying cause for the sudden hearing loss could be found. They were included in NISSNHL-group (54% male, 46% female, mean age 58.7 ± 15.8 years). 46% had acute otitis media, 37% had an acute infection with varicella zoster or Borrelia and 10% had Menière disease (Fig. 1b). The gender distribution was the same in both groups (p = 0.218). There was no side predominance of acute hearing loss neither in ISSNHL nor in NISSNHL (p = 0.197). The accompanying symptoms like tinnitus (ISSNHL: 62%; NISSNHL 51%; p = 0.743) or vertigo (ISSNHL: 30%; NISSNHL 32%; p = 0.605) occurred equally frequently in both groups (Table 1). There was no significant difference in the patients´ comorbidities either. Nicotine abuse (p = 0.117), coronary heart disease (p = 0.601), diabetes mellitus type II (p = 0.414), hypercholesterolemia (p = 0.755) and arterial hypertension (p = 0.754) occurred equally frequently in ISSNHL and NISSNHL (Table 2). More patients with NISSNHL (45%) than with ISSNHL (35%) received a prior outpatient treatment before admission to the hospital (p < 0.001). The time from the onset of hearing loss to hospital admission was less for NISSNHL (7.7 days ± 12.2 days) than for ISSNHL (8.9 days ± 11.8 days; p = 0.02). The majority of the patients (98.1%) received prednisolone therapy during the inpatient stay (100% in the NISSNHL group vs. 97.8% in the ISSNHL group; p = 0.166). Patients with NISSNHL had to undergo surgery during the hospital stay more often (52%) than patients with ISSNHL (29%; p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of distribution of the diagnoses of a non-idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (NISSNHL) and b idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (ISSNHL)

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and symptoms of patients with idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (ISSNHL) and patients with non-idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (NISSNHL)

| Patients´ characteristics | All patients | NISSNHL | ISSNHL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | p | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 294 | 51.2 | 45 | 53.6 | 251 | 50.8 | 0.218 |

| Female | 280 | 48.8 | 39 | 46.6 | 239 | 49.2 | |

| Side | |||||||

| Right | 277 | 48.3 | 46 | 54.8 | 231 | 47.1 | 0.197 |

| Left | 297 | 51.7 | 38 | 45.2 | 259 | 52.9 | |

| Tinnitus | |||||||

| Yes | 351 | 61.1 | 49 | 51.4 | 302 | 61.6 | 0.743 |

| No | 214 | 37.3 | 33 | 31.3 | 181 | 36.9 | |

| n.a | 9 | 1.6 | 2 | 2.4 | 7 | 1.4 | |

| Vertigo | |||||||

| Yes | 175 | 30.5 | 27 | 32.1 | 148 | 30.2 | 0.605 |

| No | 396 | 69 | 56 | 66.7 | 340 | 69.4 | |

| n.a | 3 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 57.2 | 16.0 | 55.7 | 15.9 | 58.7 | 15.8 | 0.100 |

n.a. not available, SD standard deviation

Table 2.

Comorbidities of patients with idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (ISSNHL) and patients with non-idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (NISSNHL)

| Patients´ characteristics | All patients | NISSNHL | ISSNHL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | p | |

| Smoking | |||||||

| Yes | 93 | 16.2 | 20 | 23.8 | 73 | 14.9 | 0.117 |

| No | 471 | 82.1 | 63 | 75 | 408 | 83.3 | |

| n.a | 10 | 1.7 | 1 | 1.2 | 9 | 1.8 | |

| Coronary heart disease | |||||||

| Yes | 68 | 11.5 | 11 | 13.1 | 57 | 11.6 | 0.601 |

| No | 503 | 87.6 | 72 | 85.7 | 431 | 88 | |

| n.a | 3 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Diabetes | |||||||

| Yes | 92 | 16 | 16 | 19 | 76 | 15.5 | 0.414 |

| No | 482 | 84 | 68 | 81 | 414 | 84.5 | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | |||||||

| Yes | 76 | 13.2 | 13 | 15.5 | 63 | 12.9 | 0.755 |

| No | 493 | 85.9 | 70 | 83.3 | 423 | 86.3 | |

| n.a | 5 | 0.9 | 1 | 1.2 | 4 | 0.8 | |

| Arterial hypertension | |||||||

| Yes | 319 | 55.6 | 48 | 57.1 | 271 | 55.3 | 0.754 |

| No | 255 | 44.4 | 36 | 42.9 | 219 | 44.7 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||||

| Yes | 187 | 67.2 | 30 | 35.7 | 157 | 32 | 0.742 |

| No | 386 | 32.6 | 54 | 64.3 | 332 | 67.8 | |

| n.a | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.2 | |

n.a. not available

Table 3.

Therapy of patients with idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss (ISSNHL) and non-idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss (NISSNHL)

| Parameters | All patients | NISSNHL | ISSNHL | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Outpatient | |||||||

| pretreatment | |||||||

| Yes | 210 | 36.6 | 38 | 45.2 | 172 | 35.1 | < 0.001 |

| No | 362 | 63.1 | 44 | 52.4 | 318 | 64.9 | |

| n.a | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Inpatient | |||||||

| prednisolone | |||||||

| treatment | |||||||

| Yes | 563 | 98.1 | 84 | 100 | 479 | 97.8 | 0.166 |

| No | 11 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 2.2 | |

| Surgical Treatment | |||||||

| Yes | 186 | 32.4 | 44 | 52.4 | 142 | 29.0 | < 0.001 |

| No | 388 | 67.6 | 40 | 47.6 | 348 | 71 | |

| Interval onset of hearing loss to inpatient treatment | days | SD | days | SD | |||

| 7.7 | 12.2 | 8.9 | 11.8 | 0.020 | |||

n.a. not available, Significant p-values (p < 0.05) in bold, SD standard deviation

Hearing loss and recovery

The average initial hearing loss of the three most affected frequencies (3PTAmax) at NISSNHL was 67.4 dBHL ± 30.5dBHL and showed no statistical difference to hearing loss at ISSNHL with a 3PTAmax of 72.9 dBHL ± 31.3 dB (p = 0.124). Considering the 10PTA, 9PTA, 4PTA, LF-3PTA and MF-3PTA ISSNHL had more severe hearing loss than NISSNHL (p < 0.05) (Table 4). The pre- and post-treatment hearing level showed a significant improvement in 10PTA, 9PTA, 4PTA, LF-3PTA, MF-3PTA, HF-2PTA and 3PTAmax in NISSNHL and ISSNHL (Table 5). Under therapy, patients with NISSNHL improved by 10.2 dB ± 17.6 dB and patients with ISSNHL by 8.1 dB ± 18.8 dB considering the 3PTAmaxabs. There was no statistically significant difference in NISSNHL and ISSNHL considering the ΔPTAabs, the ΔPTArel and the ΔPTArelcontral in all endpoints (p > 0.05) (Table 5). If ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB was used as the measure of successful hearing recovery, there was a significant difference in both groups: 48.8% of the NISSNHL, showed a hearing improvement of ≥ 10 dB in Δ3PTAmaxabs, while for ISSNHL only 34.3% had a corresponding hearing improvement (p = 0.011). In LF-3PTA 27.4% of NISSNHL and 42% of ISSNHL reached ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (p = 0.011) and 17.9% of NISSNHL and 32.2% of ISSNHL reached ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB. Other parameters showed no difference in NISSNHL and ISSNHL (Table 6).

Table 4.

Mean hearing loss in all patients and in patients with idiopathic (ISSNHL) and non-idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (NISSNHL)

| Parameter | all Mean (dBHL) | SD (dBHL) | ISSNHL Mean (dBHL) | SD (dBHL) | NISSNHL Mean (dBHL) | SD (dBHL) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10PTA, dBHL | 56.4 | 31.4 | 58.0 | 31.7 | 47.0 | 28.1 | 0.003 |

| 9PTA, dBHL | 56.6 | 31.1 | 58.2 | 31.4 | 47.6 | 27.9 | 0.004 |

| 4PTA, dBHL | 55.9 | 32.9 | 57.8 | 33.1 | 44.5 | 29.4 | 0.000 |

| LF-3PTA, dBHL | 50.4 | 32.8 | 52.8 | 32.8 | 36.5 | 29.6 | 0.000 |

| MF-3PTA, dBHL | 59.4 | 34.2 | 60.8 | 34.6 | 51.2 | 30.6 | 0.016 |

| HF-2PTA, dBHL | 68.0 | 37.1 | 68.3 | 37.5 | 66.1 | 34.6 | 0.616 |

| 3PTAmax, dBHL | 72.1 | 31.2 | 72.9 | 31.3 | 67.4 | 30.5 | 0.124 |

10PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 1.5; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 9PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 4PTA: (0.5; 1; 2; 4 kHz), LF3PTA (0.125; 0.5; 1 kHz) MF3PTA (2; 3; 4 kHz), HF2PTA (6; 8 kHz), 3PTAmax (PTA of the three most affected frequencies)

Table 5.

Pre- and post-treatment hearing level, overall absolute and relative hearing improvement on the affected ear in patients with idiopathic and non-idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss

| Parameter | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | Absolute hearing gain, ΔPTAabs | Relative hearing gain, ΔPTArel | Relative hearing gain contralateral, ΔPTArelcontral | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (dBHL) | SD (dBHL) | Mean (dBHL) | SD (dBHL) | p | Mean (dB) | SD (dB) | p | Mean (%) | SD (%) | p | Mean (%) | SD (%) | p | |

| 10PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| ISSNHL | 58.0 | 31.7 | 51.2 | 36.0 | < 0.001 | 6.8 | 16.3 | 0.881 | 14.1 | 30.3 | 0.408 | 17.2 | 150.3 | 0.089 |

| NISSNHL | 47.0 | 28.1 | 40.4 | 30.3 | < 0.001 | 6.7 | 16.8 | 14.8 | 32.3 | 88.0 | 545.6 | |||

| 9PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| ISSNHL | 58.2 | 31.4 | 51.5 | 35.7 | < 0.001 | 6.7 | 16.3 | 0.797 | 13.8 | 30.0 | 0.409 | 17.4 | 141.6 | 0.099 |

| NISSNHL | 47.6 | 27.9 | 41.0 | 30.3 | < 0.001 | 6.6 | 16.8 | 14.7 | 32.1 | 82.1 | 488.0 | |||

| 4PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| ISSNHL | 57.8 | 33.1 | 50.6 | 37.2 | < 0.001 | 7.2 | 17.0 | 0.791 | 13.3 | 43.5 | 0.544 | 20.6 | 121.9 | 0.076 |

| NISSNHL | 44.5 | 29.4 | 38.0 | 31.6 | < 0.001 | 6.5 | 17.9 | 13.8 | 44.3 | 31.1 | 103.7 | |||

| LF-3PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| ISSNHL | 52.8 | 32.8 | 43.8 | 36.4 | 0.001 | 9.0 | 18.7 | 0.051 | 17.6 | 43.5 | 0.563 | 27.6 | 76.8 | 0.564 |

| NISSNHL | 36.5 | 29.6 | 31.4 | 30.5 | 0.001 | 5.1 | 18.9 | 5.6 | 79.3 | 6.2 | 289.9 | |||

| MF-3PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| ISSNHL | 60.8 | 34.6 | 54.9 | 38.8 | < 0.001 | 5.9 | 17.8 | 0.274 | 11.0 | 35.1 | 0.135 | 31.3 | 145.7 | 0.172 |

| NISSNHL | 51.2 | 30.6 | 43.2 | 32.1 | < 0.001 | 8.0 | 18.9 | 16.0 | 34.3 | 22.7 | 131.4 | |||

| HF-2PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| ISSNHL | 68.3 | 37.5 | 63.6 | 39.5 | 0.001 | 4.6 | 23.5 | 0.134 | 6.6 | 33.6 | 0.081 | 15.3 | 121.5 | 0.145 |

| NISSNHL | 66.1 | 34.6 | 58.9 | 37.9 | 0.001 | 7.2 | 18.9 | 12.5 | 27.1 | 12.7 | 88.4 | |||

| 3PTAmax dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| ISSNHL | 72.9 | 31.3 | 65.2 | 34.5 | < 0.001 | 8.1 | 18.8 | 0.152 | 12.3 | 29.1 | 0.131 | |||

| NISSNHL | 67.4 | 30.5 | 57.2 | 31.6 | < 0.001 | 10.2 | 17.6 | 15.4 | 25.9 | |||||

10PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 1.5; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 9PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 4PTA: (0.5; 1; 2; 4 kHz), LF3PTA (0.125; 0.5; 1 kHz) MF3PTA (2; 3; 4 kHz), HF2PTA (6; 8 kHz), 3PTAmax (PTA of the three most affected frequencies), ΔPTAabs (Absolute hearing gain), ΔPTArel (Relative hearing gain), ΔPTArelcontral (Relative hearing gain contralateral)

Table 6.

Hearing recovery rates in patients with idiopathic and non-idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss

| Parameter | ISSNHL (n = 490) | NISSNHL (n = 84) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10PTA, dBHL | |||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 34.9 | 28.6 | 0.258 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 24.1 | 15.5 | 0.083 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 13.9 | 9.5 | 0.277 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 29.2 | 33.3 | 0.443 |

| 9PTA, dBHL | |||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 34.7 | 27.4 | 0.190 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 23.1 | 16.7 | 0.192 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 13.7 | 9.5 | 0.298 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 30 | 33.3 | 0.540 |

| 4PTA, dBHL | |||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 36.7 | 29.8 | 0.218 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 25.5 | 19 | 0.204 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 15.7 | 9.5 | 0.140 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 30.2 | 39.3 | 0.098 |

| LF-3PTA, dBHL | |||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 42 | 27.4 | 0.011 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 32.2 | 17.9 | 0.008 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 21 | 17.9 | 0.508 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 32.7 | 38.1 | 0.329 |

| MF-3PTA, dBHL | |||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 29.4 | 33.3 | 0.466 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 22.4 | 23.8 | 0.783 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 12.9 | 14.3 | 0.720 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 28.8 | 38.1 | 0.086 |

| HF-2PTA, dBHL | |||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 28 | 38.1 | 0.060 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 20.4 | 21.4 | 0.831 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 10.2 | 9.5 | 0.849 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 26.9 | 28.6 | 0.756 |

| 3PTAmax, dBHL | |||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 34.3 | 48.8 | 0.011 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 25.9 | 28.6 | 0.610 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 10.2 | 8.3 | 0.597 |

10PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 1.5; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 9PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 4PTA: (0.5; 1; 2; 4 kHz), LF3PTA (0.125; 0.5; 1 kHz) MF3PTA (2; 3; 4 kHz), HF2PTA (6; 8 kHz), 3PTAmax (PTA of the three most affected frequencies), ΔPTAabs (Absolute hearing gain), ΔPTArel (Relative hearing gain), ΔPTArelcontral (Relative hearing gain contralateral)

The subgroup analysis of patients with NISSNHL showed that patients with acute otitis media with 3PTAmax of 59.7 dBHL ± 24.6 dBHL and Menière disease with 3PTAmax of 50.4 dBHL ± 12.04 dBHL had a significantly lower initial hearing loss than the other subgroups (p = 0.033) (Table 7). The pre- and post-treatment hearing level showed significant differences for 3PTAmax in all subgroups. However, ΔPTAabs, ΔPTArel and ΔPTArelcontral showed no differences between the subgroups (Table 8). If ΔPTArel ≥ 50% and ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% was used as success criteria for a hearing recovery, it could be seen that the same number of patients from all subgroups met the criterion. For ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB and ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB we could show a difference in the hearing recovery rate in between the subgroups for LF-3PTA. 12,8% of patient with acute otitis media, 45,2% of patients with varicella zoster or Borrelia, 25% of patients with Menière disease and 16.7% others met the ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB for the LF-3PTA (p = 0.021) (Table 9).

Table 7.

Mean hearing loss in subgroups of non-idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (NISSNHL)

| Parameter | AOM Mean (dBHL) | SD (dBHL) | VZB Mean (dBHL) | SD (dBHL) | M Mean (dBHL) | SD (dBHL) | O Mean (dBHL) | SD (dBHL) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10PTA, dBHL | 36.9 | 16.5 | 62.5 | 34.7 | 32.7 | 9.3 | 52.3 | 32.0 | 0.007 |

| 9PTA, dBHL | 37.7 | 16.8 | 62.7 | 34.4 | 33.8 | 9.4 | 52.8 | 32.0 | 0.010 |

| 4PTA, dBHL | 32.8 | 14.5 | 62.4 | 36.6 | 27.5 | 9.5 | 50.6 | 31.2 | 0.001 |

| LF-3PTA, dB HL | 21.5 | 13.9 | 55.8 | 35.7 | 33.5 | 7.9 | 38.9 | 35.5 | 0.000 |

| MF-3PTA, dBHL | 43.1 | 17.9 | 66.3 | 37.8 | 25.4 | 15.0 | 60.6 | 32.8 | 0.002 |

| HF-2PTA, dBHL | 62.3 | 29.8 | 75.6 | 38.7 | 41.3 | 18.8 | 75.4 | 43.1 | 0.062 |

| 3PTAmax dBHL | 59.7 | 24.6 | 80.1 | 34.2 | 50.4 | 12.0 | 74.7 | 40.2 | 0.033 |

AOM Acute otitis media, VZB Varicella zoster/Borrelia, M Menière disease, O Other cause, 10PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 1.5; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 9PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 4PTA: (0.5; 1; 2; 4 kHz), LF3PTA (0.125; 0.5; 1 kHz) MF3PTA (2; 3; 4 kHz), HF2PTA (6; 8 kHz), 3PTAmax (PTA of the three most affected frequencies)

Table 8.

Pre- and post-treatment hearing level, overall absolute and relative hearing improvement on the affected ear in subgroups of patients with non-idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss

| Parameter | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | Absolute hearing gain, ΔPTAabs | Relative hearing gain, ΔPTArel | Relative hearing gain contralateral, ΔPTArelcontral | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (dBHL) | SD (dBHL) | Mean (dBHL) | Mean (dBHL) | p | Mean (dB) | SD (dB) | p | Mean (%) | SD (%) | p | Mean (%) | SD (%) | p | |

| 10PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| AOM | 36.9 | 16.5 | 29.9 | 15.0 | < 0.001 | 7.0 | 8.6 | 0.796 | 18.9 | 21.3 | 0.336 | 160.6 | 796.5 | 0.526 |

| VZB | 62.5 | 34.7 | 54.6 | 38.9 | 0.044 | 7.9 | 24.7 | 11.2 | 42.4 | 24.7 | 75.6 | |||

| MD | 32.7 | 9.3 | 27.1 | 14.7 | 0.161 | 5.6 | 10.1 | 21.7 | 35.8 | 40.9 | 64.9 | |||

| O | 52.3 | 32.0 | 65.9 | 42.1 | 0.114 | 3.4 | 15.5 | − 2.3 | 24.5 | 5.7 | 46.1 | |||

| 9PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| AOM | 37.7 | 16.8 | 30.7 | 15.2 | < 0.001 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 0.783 | 18.5 | 21.3 | 0.292 | 145.8 | 711.3 | 0.565 |

| VZB | 62.7 | 34.4 | 55.1 | 38.7 | 0.056 | 7.7 | 24.8 | 11.2 | 42.1 | 26.9 | 81.8 | |||

| MD | 33.8 | 9.4 | 27.6 | 14.9 | 0.123 | 6.3 | 10.3 | 22.7 | 35.5 | 42.2 | 64.6 | |||

| O | 52.8 | 32.0 | 66.1 | 41.9 | 0.138 | 3.2 | 15.6 | − 2.4 | 24.1 | 5.4 | 48.0 | |||

| 4PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| AOM | 32.8 | 14.5 | 25.9 | 13.1 | < 0.001 | 6.9 | 8.3 | 0.691 | 20.6 | 22.3 | 0.442 | 50.7 | 80.0 | 0.380 |

| VZB | 62.4 | 36.6 | 54.4 | 40.8 | 0.118 | 8.0 | 26.5 | 6.4 | 62.2 | 10.3 | 137.3 | |||

| MD | 27.5 | 9.5 | 24.4 | 15.8 | 0.483 | 3.1 | 12.7 | 19.0 | 52.8 | 31.6 | 79.0 | |||

| O | 50.6 | 31.2 | 65.0 | 43.3 | 0.073 | 4.5 | 16.2 | 0.5 | 26.8 | 10.4 | 44.4 | |||

| LF-3PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| AOM | 21.5 | 13.9 | 18.5 | 12.3 | 0.005 | 3.0 | 8.0 | 0.515 | 5.1 | 77.2 | 0.770 | 40.9 | 180.8 | 0.912 |

| VZB | 55.8 | 35.7 | 46.5 | 38.8 | 0.034 | 9.2 | 28.3 | 5.5 | 95.1 | − 39.9 | 424.1 | |||

| MD | 33.5 | 7.9 | 29.8 | 17.4 | 0.484 | 3.8 | 15.4 | 13.4 | 51.3 | 23.0 | 79.0 | |||

| O | 38.9 | 35.5 | 58.1 | 43.5 | 0.020 | 5.3 | 17.3 | − 2.0 | 37.3 | 13.6 | 74.0 | |||

| MF-3PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| AOM | 43.1 | 17.9 | 33.8 | 17.0 | < 0.001 | 9.3 | 10.6 | 0.28 | 21.5 | 23.8 | 0.284 | 45.4 | 64.0 | 0.301 |

| VZB | 66.3 | 37.8 | 58.1 | 41.1 | 0.189 | 8.2 | 26.2 | 9.8 | 42.9 | − 10.6 | 196.5 | |||

| MD | 25.4 | 15.0 | 20.6 | 12.9 | 0.310 | 4.8 | 11.9 | 23.8 | 42.0 | 49.1 | 82.1 | |||

| O | 60.6 | 32.8 | 69.8 | 44.1 | 0.638 | 3.3 | 19.1 | 0.8 | 30.5 | 12.4 | 48.8 | |||

| HF-2PTA, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| AOM | 62.3 | 29.8 | 52.2 | 28.9 | < 0.001 | 10.1 | 17.0 | 0.093 | 15.6 | 22.9 | 0.097 | 14.2 | 95.8 | 0.577 |

| VZB | 75.6 | 38.7 | 70.6 | 44.8 | 0.502 | 5.0 | 23.4 | 8.5 | 34.1 | 18.3 | 53.7 | |||

| MD | 41.3 | 18.8 | 32.8 | 16.6 | 0.017 | 8.4 | 9.0 | 22.0 | 21.1 | − 12.6 | 162.9 | |||

| O | 75.4 | 43.1 | 78.6 | 43.8 | 0.602 | 0.6 | 17.6 | − 0.8 | 11.1 | 11.2 | 44.0 | |||

| 3PTAmax, dBHL | ||||||||||||||

| AOM | 59.7 | 24.6 | 49.5 | 23.4 | < 0.001 | 10.2 | 13.3 | 0.671 | 16.9 | 20.6 | 0.324 | |||

| VZM | 80.1 | 34.2 | 69.2 | 37.6 | 0.003 | 10.9 | 23.6 | 13.5 | 31.4 | |||||

| MD | 50.4 | 12.0 | 38.3 | 17.7 | 0.042 | 12.1 | 14.3 | 25.2 | 31.5 | |||||

| O | 74.7 | 40.2 | 76.2 | 37.6 | 0.016 | 5.6 | 15.6 | 2.0 | 13.1 | |||||

AOM Acute otitis media, VZB Varicella zoster/Borrelia, MMenière disease, O Other cause, 10PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 1.5; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 9PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 4PTA: (0.5; 1; 2; 4 kHz), LF3PTA (0.125; 0.5; 1 kHz) MF3PTA (2; 3; 4 kHz), HF2PTA (6; 8 kHz), 3PTAmax (PTA of the three most affected frequencies), ΔPTAabs (Absolute hearing gain), ΔPTArel (Relative hearing gain), ΔPTArelcontral (Relative hearing gain contralateral)

Table 9.

Hearing recovery rates in subgroups of pathients with non-idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss

| Parameter | AOM | VZB | M | O | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10PTA, dBHL | |||||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 23.1 | 35.5 | 37.5 | 16.7 | 0.571 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 10.3 | 19.4 | 25 | 16.7 | 0.635 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 7.7 | 9.7 | 25 | 0 | 0.396 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 33.3 | 35.5 | 37.5 | 16.7 | 0.833 |

| 9PTA, dBHL | |||||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 23.1 | 32.3 | 25 | 16.7 | 0.688 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 12.8 | 19.4 | 25 | 16.7 | 0.810 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 7.7 | 9.7 | 25 | 0 | 0.395 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 35.9 | 32.3 | 37.5 | 16.7 | 0.818 |

| 4PTA, dBHL | |||||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 28.2 | 35.5 | 37.5 | 16.7 | 0.778 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 15.4 | 22.6 | 25 | 16.7 | 0.853 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 7.7 | 9.7 | 25 | 0 | 0.396 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 46.2 | 32.3 | 50 | 16.7 | 0.384 |

| LF-3PTA, dBHL | |||||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 12.8 | 45.2 | 25 | 16.7 | 0.021 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 5.1 | 32.3 | 37.5 | 0 | 0.008 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 15.4 | 22.6 | 25 | 0 | 0.534 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 38.5 | 41.9 | 25 | 33.3 | 0.843 |

| MF-3PTA, dBHL | |||||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 35.9 | 35.5 | 25 | 16.7 | 0.761 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 25.6 | 25.8 | 12.5 | 16.7 | 0.834 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 17.9 | 6.5 | 37.5 | 0 | 0.093 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 41 | 35.5 | 25 | 33.3 | 0.962 |

| HF-2PTA, dBHL | |||||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 41 | 35.5 | 50 | 16.7 | 0.602 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 28.2 | 19.4 | 12.5 | 16.7 | 0.816 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 5.1 | 12.9 | 25 | 0 | 0.252 |

| ΔPTArelcontral ≥ 50% (%) | 30.8 | 25.8 | 37.5 | 16.7 | 0.819 |

| 3PTAmax, dBHL | |||||

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 10 dB (%) | 51.3 | 48.4 | 50 | 33.3 | 0.880 |

| ΔPTAabs ≥ 15 dB (%) | 7.7 | 25.8 | 50 | 16.7 | 0.511 |

| ΔPTArel ≥ 50% (%) | 5.1 | 9.7 | 25 | 0 | 0.261 |

AOM: Acute otitis media, VZB: Varicella zoster/Borrelia, M:Menière disease, O: Other cause, 10PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 1.5; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 9PTA (0.125; 0.25; 0.5; 1; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8 kHz), 4PTA: (0.5; 1; 2; 4 kHz), LF3PTA (0.125; 0.5; 1 kHz) MF3PTA (2; 3; 4 kHz), HF2PTA (6; 8 kHz), 3PTAmax (PTA of the three most affected frequencies), ΔPTAabs (Absolute hearing gain), ΔPTArel (Relative hearing gain), ΔPTArelcontral (Relative hearing gain contralateral)

The univariate analysis of the prognostic factors showed that among the patients with NISSNHL patients without vertigo more often had a successful hearing impairment Δ3PTAmaxabs ≥ 10 dB (p = 0.027) and that more patients with prior outpatient treatment showed a hearing impairment of Δ3PTAmaxabs ≥ 10 dB (p = 0.032). There was no difference for the tinnitus (p = 0.325), as well as for the comorbidities of coronary heart disease (p = 0.531), hypercholesterolemia (p = 0.439), diabetes mellitus type II (p = 0.653) and arterial hypertension (p = 0.850) (Table 10).

Table 10.

Univariate association between patients’ and treatment characteristics versus a successful recovery defined as Δ3PTAmaxabs ≥ 10 dB (N = 84)

| Parameter | Δ3PTAmaxabs˂10 dB | Δ3PTAmaxabs ≥ 10 dB | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients´characteristics | |||

| Gender | 0.083 | ||

| Male | 27 | 18 | |

| Female | 16 | 23 | |

| Side | 0.524 | ||

| Right | 25 | 21 | |

| Left | 18 | 20 | |

| Tinnitus | 0.325 | ||

| Yes | 25 | 24 | |

| No | 16 | 17 | |

| n.a | 2 | 0 | |

| Vertigo | 0.027 | ||

| Yes | 19 | 8 | |

| No | 23 | 33 | |

| n.a | 1 | 0 | |

| Smoking | 0.557 | ||

| Yes | 11 | 9 | |

| No | 32 | 31 | |

| n.a | 0 | 1 | |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.531 | ||

| Yes | 5 | 6 | |

| No | 38 | 34 | |

| n.a | 0 | 1 | |

| Diabetes mellitus type II | 0.653 | ||

| Yes | 9 | 7 | |

| No | 34 | 34 | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.439 | ||

| Yes | 8 | 5 | |

| No | 35 | 35 | |

| n.a | 0 | 1 | |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.850 | ||

| Yes | 25 | 23 | |

| No | 18 | 18 | |

| Comorbidity | 0.454 | ||

| Yes | 17 | 13 | |

| No | 26 | 23 | |

| Prior outpatient treatment | 0.032 | ||

| Yes | 14 | 24 | |

| No | 27 | 17 | |

| n.a | 2 | 0 | |

| Surgical treatment | 0.835 | ||

| Yes | 23 | 21 | |

| No | 20 | 20 |

3PTAmax (PTA of the three most affected frequencies), ΔPTAabs (Absolute hearing gain)

The multivariate analysis showed that neither vertigo nor prior outpatient treatment were independent factors associated with better hearing recovery (Table 11).

Table 11.

Multivariate binary regression of predictors of successful improvement of hearing Δ3PTAmaxabs ≥ 10 dB

| Parameter | B | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertigo | 0.009 | − 0.096 | 0.114 | 0.865 |

| Prior outpatient treatment | − 0.001 | 0.397 | − 0.002 | 0.397 |

CI confidence interval

Epidemiology

Thuringia had an average of 2,176,031 (female: 1,105,434, male: 1,070,597) inhabitants in 2011 and 2012. In total, an average of 16.61 inpatients per 100,000 habitants was treated in Thuringia per year. Of these, 11.25 inpatients per 100,000 habitants had an ISSNHL and 1.93 per 100,000 inhabitant people per year had an NISSNHL (0.89/100,000 for acute otitis media, 0.71/100,000 for varicella zoster or Borrelia and 0.18/100,000 for Menière disease). There was no difference in gender distribution. The incidence of the ISSNHL was 21.6/100,000 in women and 23.4/100,000 in men. The incidence of NISSNHL was 3.5/100,000 in women and 4.2/100,000 in men.

Discussion

Key findings

In the current study, causes for sensorineural hearing losses were found in 14.6%, which corresponds to the numbers reported so far [7]. There were no differences between patients with ISSNHL and NISSNHL in terms of risk factors and accompanying symptoms. The extent of the initial absolute hearing loss tended to be higher in patients with ISSNHL compared to NISSNHL but the absolute and relative hearing recovery showed no difference. If according to Plontke et al. an absolute improvement of the pure tone average by ≥ 10 dB is used as a criterion for a successful hearing recovery, it can be seen that patients with NISSNHL show a successful hearing recovery more often than patients with ISSNHL considering the Δ3PTAmaxabs [13]. An explanatory model offers the possibility of using specific therapy options in the case of NISSNHL (acyclovir, antibiotics) [17, 18], while at ISSNHL therapy decisions are made without knowledge of the etiology of the hearing loss [7].

Strength and limitations

Studies that directly compare ISSNHL and NISSNHL are not known. Therefore, the retrospective study presented here with a total of 490 patients with ISSNHL and 84 patients with NISSNHL is the largest study of this type published to date. One disadvantage of the current study is that only patients with acute hearing loss were included here. Patients treated in hospital with the ICD codes H65.0, H65.1, H65.2, H65.3 H65.4 H65.9, H66.0, H66.1, H66.2, H66.3, H66.4, H66.9, H67.0* H67.1*, H67.8*, H83.0, H73.0, J11.8,H70.0, H70.2, H70 0.8, H70.9, B02.8 and A69.2 for any underlying disease were not included. Therefore, there is an unreported number of patients with other diseases combined with sensorineural hearing loss. Likewise, the true incidence of diseases is underestimated here because only patients who have been hospitalized are included in this evaluation. This is associated with a selection bias in favor of the more severe cases. The evaluation of hearing loss and hearing gain is handled inconsistently in most studies [19–21]. So far, there is no consensus on the evaluation of hearing loss and hearing recovery in the pure tone audiogram [13]. The different criteria for evaluating the hearing loss and hearing gain make it difficult to compare studies with one another. In addition, the evaluation of different endpoints in this analysis also shows different results.

Comparison with other studies

The data on the occurrence, extent and recovery of ISSNHL have already been discussed in detail elsewhere [3]. Therefore, we now focus on the data of NISSNHL. The incidence of acute otitis media is 10.85% [22]. The incidence of zoster oticus is 5 / 100,000 inhabitants [23]. The incidence of Lyme disease is 0.04 / 100,000 inhabitants, which is strongly dependent on the region [24]. Menière disease has an incidence of 200 / 100,000 inhabitants [25]. The epidemiological data diverge greatly in the evaluation published here. The reason might be that, as mentioned before, ICD-codes for underlying illnesses of hearing loss are not included here.

In addition to potentially life-threatening complications, acute otitis media can lead to a permanent impairment of the patient due to hearing loss [22]. A zoster oticus can lead to accompanying facial palsy or vestibular failure in the context of Ramsay Hunt syndrome [20, 26]. Overall, the detection of Borrelia titers is controversial in the diagnosis of acute hearing loss. Numerous studies have shown a connection between Borrelia detection and sudden hearing loss, while others see no connection [27–32]. In Menière disease, hearing loss is one of the diagnostic criteria of the Bárány Society and the AAO-HNS guideline [33, 34]. It is noticeable that hearing impairment has different values in the underlying diseases. While in acute otitis media there is a complicated course in the case of sensorineural hearing loss, the detection of at least one episode of sensorineural hearing loss is a prerequisite for the diagnosis of Menière disease.

In the present study, it was found that acute otitis media and Menière disease showed significantly less absolute hearing loss compared to the other subgroups. Many evaluations consider hearing loss, but often no distinction is made between the appearance of conductive hearing loss and sensorineural hearing loss. Occasionally the absolute extent of hearing loss (in dBHL) is not described. For acute otitis media hearing loss is reported between 25 and 40 dBHL [19, 22, 35–37]. Hearing loss in zoster oticus is reported in 7–85% of patients with an extend of 10dBHL to 20dBHL [20, 21, 38–40], while hearing loss in case of Borrelia infection is considered in approximately 12% [41]. The largest clinical trial examining Menière disease includes 350 patients. This showed fluctuating curves in the pure tone audiogram at the beginning of the disease and an average hearing threshold of 26 to 40 dBHL[42]. In summary, one subgroup in this study showed a higher absolute hearing loss in the used endpoints (Varicella / Borrelia: range 55.8dBHL – 80.1dBHL), whereas initial PTA of the others (acute otitis media: range 21.5dBHL – 59.7dBHL, Menière disease range: 25.4—50.42 dBHL) considering the different endpoints is the same as reported in the underlying literature. Explanations might be the already mentioned bias to more severe cases and difficulties in comparison of different studies reporting a hearing loss.

So far, there is no guideline for the treatment of acute otitis media with sensorineural hearing loss in Germany. The German Society for General Medicine and Family Medicine published a S2k-guideline "Earache": In the guideline, initially symptomatic treatment and, in the event of a lack of improvement or indications of a complicated course, antibiotics are used [43]. In acute otitis media, the patients in the studies considered were treated with oral antibiotics [19, 36]. Oral corticosteroids and paracentesis with or without tympanic drainage were optionally performed [19]. Patients with herpes zoster oticus were treated intravenously with acyclovir [44]. There is a German S2k-guideline in which anti-viral therapy in combination with glucocorticoid therapy is recommended for zoster oticus, but this guideline does not give specific recommendations regarding a related sensorineural hearing loss [45]. Patients with Lyme disease are treated with ceftriaxone or doxycycline depending on the stage of the disease [41]. The treatment strategies in the current study thus corresponded to current treatment recommendations. In 87.5% of cases with acute otitis media and sensorineural hearing loss there was an improvement in hearing of at least 10 dB on average with 5PTA (500 Hz, 1 kHz, 2 kHz, 3 kHz, 4 kHz) [19]. In the current evaluation, there was no difference in hearing improvement after therapy in between all subgroups.

Conclusion

The current retrospective study examines inpatients with ISSNHL and NISSNHL in Thuringia in 2011 and 2012. It can be seen that ISSNHL tends to have a higher initial hearing loss than patients with NISSNHL. ISSNHL and NISSNHL show no difference in the degree of absolute or relative hearing improvement. However, patients with NISSNHL are more likely to show successful hearing improvement considering the 3PTAmax. The data are not sufficient to show prognostic differences of subgroups at NISSNHL. However, we were able to show that patients with acute otitis media and Menière disease show an initially lower hearing loss compared to patients with varicella zoster or Lyme disease or other underlying diseases.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file 1 (TIF 12771 KB) Supplemental Digital Content 1. Inclusion and exclusion of patients´ datasets. 574 patients were analyzed. 490 patients had an ISSNHL (idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss), 84 patients had a NISSNHL (non-idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss).

Author contributions

OGL developed the idea for the study. JT made the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed patients’ data to the study. AH administered the database. AH and OGL revised the final database. JT performed the statistical analyses. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors revised the manuscript. JT is the guarantor.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data availability

All authors had full access to all of the data in the study. JT takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. No additional data are available.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wu CS, et al. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss associated with chronic periodontitis: a population-based study. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(8):1380–1384. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182a1e925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander TH, Harris JP. Incidence of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(9):1586–1589. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heuschkel A, et al. Inpatient treatment of patients with idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a population-based healthcare research study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275(3):699–707. doi: 10.1007/s00405-018-4870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edizer DT, et al. Recovery of Idiopathic Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss. J Int Adv Otol. 2015;11(2):122–126. doi: 10.5152/iao.2015.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conlin AE, Parnes LS. Treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss: II A Meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(6):582–586. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.6.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattox DE, Simmons FB. Natural history of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86(4 Pt 1):463–480. doi: 10.1177/000348947708600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stachler RJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline: sudden hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(3 Suppl):S1–35. doi: 10.1177/0194599812436449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michel O, Ku H-C. Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Heilkunde, The revised version of the german guidelines "sudden idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngorhinootologie. 2011;90(5):290. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1273721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haynes DS, et al. Intratympanic dexamethasone for sudden sensorineural hearing loss after failure of systemic therapy. The Laryngoscope. 2007;117(1):3–15. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000245058.11866.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klemm E, Deutscher A, Mösges R. A present investigation of the epidemiology in idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 2009;88(8):524–527. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1128133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renner V, et al. Inpatient Treatment of Patients Admitted for Dizziness: A Population-Based Healthcare Research Study on Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38(10):e460–e469. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiedler T, et al. Middle ear surgery in Thuringia, Germany: a population-based regional study on epidemiology and outcome. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(5):890–897. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318280dc55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plontke SK, Bauer M, Meisner C. Comparison of pure-tone audiometry analysis in sudden hearing loss studies: lack of agreement for different outcome measures. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28(6):753–763. doi: 10.1097/mao.0b013e31811515ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suckfuell M, et al. Efficacy and safety of AM-111 in the treatment of acute sensorineural hearing loss: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase II study. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35(8):1317–1326. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanzaki J, et al. Effect of single-drug treatment on idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003;30(2):123–127. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(03)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nosrati-Zarenoe R, Hultcrantz E. Corticosteroid treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: randomized triple-blind placebo-controlled trial. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33(4):523–531. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31824b78da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chau JK, et al. Systematic review of the evidence for the etiology of adult sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(5):1011–1021. doi: 10.1002/lary.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merchant SN, Adams JC, Nadol JB., Jr Pathology and pathophysiology of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26(2):151–160. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200503000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park JH, et al. Sensorineural hearing loss: a complication of acute otitis media in adults. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271(7):1879–1884. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim CH, Choi H, Shin JE. Characteristics of hearing loss in patients with herpes zoster oticus. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(46):e5438. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaberos A, et al. Audiological assessment in Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111(1):68–76. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monasta L, et al. Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e36226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murakami S, et al. Treatment of Ramsay Hunt syndrome with acyclovir-prednisone: significance of early diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol. 1997;41(3):353–357. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizzoli A, et al. Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2011;16:27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plontke SK, Gurkov R. Meniere's Disease. Laryngorhinootologie. 2015;94(8):530–554. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1555808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walther LE, et al. Herpes zoster oticus: symptom constellation and serological diagnosis. Laryngorhinootologie. 2004;83(6):355–362. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanner P. Borreliosis may cause hearing defects in children. Screening of Borrelia infection. Lakartidningen. 1995;92(3):174–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanner P, et al. Hearing impairment in patients with antibody production against Borrelia burgdorferi antigen. Lancet. 1989;1(8628):13–15. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91673-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moscatello AL, et al. Otolaryngologic aspects of Lyme disease. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(6 Pt 1):592–595. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199106000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riechelmann H, et al. The Borrelia titer in ENT diseases. Laryngorhinootologie. 1990;69(2):65–69. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-998144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakker R, et al. No evidence for the diagnostic value of Borrelia serology in patients with sudden hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(4):539–543. doi: 10.1177/0194599811432535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saunders JE. Routine testing for Borrelia serology in sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(1):179–180. doi: 10.1177/0194599812468276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez-Escamez JA, et al. Diagnostic criteria for Meniere's disease. J Vestib Res. 2015;25(1):1–7. doi: 10.3233/VES-150549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez-Escamez JA, et al. Diagnostic criteria for Meniere's disease. Consensus document of the Barany Society, the Japan Society for Equilibrium Research, the European Academy of Otology and Neurotology (EAONO), the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) and the Korean Balance Society. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2016;67(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kasemodel, A.L.P., et al., Sensorineural hearing loss in the acute phase of a single episode of acute otitis media. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Cordeiro FP, et al. Extended high-frequency hearing loss following the first episode of otitis media. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(12):2879–2884. doi: 10.1002/lary.27309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paparella MM, et al. Sensorineural hearing loss in otitis media. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1984;93(6 Pt 1):623–629. doi: 10.1177/000348948409300616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim J, et al. Statistical analysis of pure tone audiometry and caloric test in herpes zoster oticus. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;1(1):15–19. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2008.1.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Byl FM, Adour KK. Auditory symptoms associated with herpes zoster or idiopathic facial paralysis. Laryngoscope. 1977;87(3):372–379. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197703000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wayman DM, et al. Audiological manifestations of Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104(2):104–108. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100111971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peltomaa M, et al. Lyme borreliosis, an etiological factor in sensorineural hearing loss? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;257(6):317–322. doi: 10.1007/s004059900206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savastano M, Guerrieri V, Marioni G. Evolution of audiometric pattern in Meniere's disease: long-term survey of 380 cases evaluated according to the 1995 guidelines of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. J Otolaryngol. 2006;35(1):26–29. doi: 10.2310/7070.2005.4092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mühlenfeld H-M, Saal K. Die neue DEGAM-Leitlinie Nr. 7 „Ohrenschmerzen”. ZFA-Zeitschrift für Allgemeinmedizin. 2005;81(12):544–549. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagner G, Klinge H, Sachse MM. Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10(4):238–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2012.07894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gross GE, et al. S2k-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik und Therapie des Zoster und der Postzosterneuralgie. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft. 2020;18(1):55–79. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14013_g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file 1 (TIF 12771 KB) Supplemental Digital Content 1. Inclusion and exclusion of patients´ datasets. 574 patients were analyzed. 490 patients had an ISSNHL (idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss), 84 patients had a NISSNHL (non-idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss).

Data Availability Statement

All authors had full access to all of the data in the study. JT takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. No additional data are available.