Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) centred diagnostic systems are increasingly recognised as robust solutions in healthcare delivery pathways. In turn, there has been a concurrent rise in secondary research studies regarding these technologies in order to influence key clinical and policymaking decisions. It is therefore essential that these studies accurately appraise methodological quality and risk of bias within shortlisted trials and reports. In order to assess whether this critical step is performed, we undertook a meta-research study evaluating adherence to the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 (QUADAS-2) tool within AI diagnostic accuracy systematic reviews. A literature search was conducted on all studies published from 2000 to December 2020. Of 50 included reviews, 36 performed the quality assessment, of which 27 utilised the QUADAS-2 tool. Bias was reported across all four domains of QUADAS-2. Two hundred forty-three of 423 studies (57.5%) across all systematic reviews utilising QUADAS-2 reported a high or unclear risk of bias in the patient selection domain, 110 (26%) reported a high or unclear risk of bias in the index test domain, 121 (28.6%) in the reference standard domain and 157 (37.1%) in the flow and timing domain. This study demonstrates the incomplete uptake of quality assessment tools in reviews of AI-based diagnostic accuracy studies and highlights inconsistent reporting across all domains of quality assessment. Poor standards of reporting act as barriers to clinical implementation. The creation of an AI-specific extension for quality assessment tools of diagnostic accuracy AI studies may facilitate the safe translation of AI tools into clinical practice.

Subject terms: Medical research, Diagnosis, Computational science

Introduction

With ever-expanding applications for the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare, interest in its capabilities to analyse and interpret diagnostic tests has increased. AI-driven approaches to the interpretation of diagnostic tests have the potential to overcome several current limitations on clinical review availability, time to diagnosis, diagnostic accuracy and consistency. Recently, various deep learning algorithms have demonstrated comparable or superior performance in the analysis of radiological findings as compared to experts1. In conjunction with AI, clinical diagnosticians are capable of improving measures of diagnostic accuracy (such as sensitivity and specificity, area under the curve, positive predictive and negative predictive values) as well as minimising inter- and intra-observer variability in interpretation. Similar studies have also been conducted in non-radiological diagnostics, including AI-driven analysis of endoscopic, retinal and histopathological images2–4. As studies examining AI-driven approaches to diagnostic interpretation have become prevalent, systematic reviews have increasingly been published to amalgamate and report these results. Given the diversity and heterogeneity of existing AI techniques, with further rapid expansion expected, clinicians and policymakers may find it difficult to interpret these results and implement these models in their clinical practice. Because of the substantial reliance of these models on data, the quality, quantity and type of data are all important in ensuring high algorithmic accuracy. Additionally, it is prudent to ensure included studies are of high methodological quality and employ rigorous standards of outcome reporting, as they may be influential in altering guidelines or prompting significant policy change. On the other hand, poor quality studies with a lack of transparent reporting may lead to scepticism within healthcare professionals and members of the public, therefore, leading to unnecessary delays in technological adoption. It is therefore imperative that authors of systematic reviews critically appraise literature using an evidence-based, validated quality assessment tool to enable adequate comparison between studies. In this context of rapidly evolving research techniques coupled with scientific and technological progress, assessing the use of and adherence to existing quality assessment tools can offer valuable insights into their usefulness and relevance. Furthermore, understanding the limitations of these tools is pertinent to ensuring necessary amendments can be made to best match current scientific needs.

The most widely used guideline for the methodological assessment of systematic reviews and meta-analyses is the QUADAS tool. QUADAS was created in 2003 and revised in 2011 (QUADAS-2) to categorise the fourteen questions in the original tool into four domains covering flow and timing, reference, standard and patient selection. Each domain is evaluated for biases and the first three are also assessed for applicability5,6. However, the applicability of QUADAS-2 for AI-specific studies is unknown. These studies differ methodologically from conventional trials and consist of distinctive features, techniques and a different entity of analytical challenges. Given the differences in study design and outcome reporting, the areas of potential bias are also likely to differ substantially. However, despite these assumptions, there have been no formal studies examining the adherence and suitability of QUADAS-2 in this genre of study. Moreover, there has not been a similar evaluation with respect to emerging AI-centred quality appraisal tools, such as the Radiomics Quality Score (RQS), which was specifically designed for studies reporting on algorithm-based extraction of features from medical images7.

Meta-research studies have been increasingly undertaken to evaluate the processes of research and the quality of published evidence, which facilitates the advancement of existing scientific standards. For example, Frank et al. evaluated the correlation between and publication characteristics and found that factors given high importance when assessing study reliability, such as journal impact factor, are not necessarily accurate markers of “truth”8. Such studies are imperative to highlight areas for improvement within research practices and lead to changes in guidelines, reporting standards and regulations. Moreover, recent literature has also underscored the importance of modifying and adapting current research methodologies in line with the digital shift in healthcare9. Thus, assessing the adherence to QUADAS-2 in current systematic reviews on diagnostic accuracy in AI studies is an important process in understanding its limitations and evaluating the present applicability of this tool in a digital era.

Therefore, the primary aim of this meta-research study is to evaluate adherence to the QUADAS-2 tool within systematic reviews of AI-based diagnostic accuracy. The secondary aims include (i) assessing the applicability of QUADAS-2 for AI-based diagnostic accuracy studies, (ii) identifying other tools for methodological quality assessment and (iii) identifying key features that an AI-specific quality assessment tool for diagnostic accuracy reporting should incorporate.

Results

Literature search

The search yielded 135 papers after the removal of duplicates, of which 48 met the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Of 87 excluded, 32 were entirely irrelevant to artificial intelligence, 39 focused on prognostication or prediction, 12 were not systematic reviews and 4 were protocols for systematic reviews. Three papers were excluded upon full-text review as the systematic reviews focussed upon prediction models. Two papers were excluded due to a lack of focus on AI-based diagnostics. Four studies were excluded as they solely discussed the types and methodologies of AI-based tools. Two studies were excluded as they did not specify the investigation type.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram for systematic literature search and study selection.

PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Study characteristics

A total of 1110 studies were included across all 48 systematic reviews, with an average of 23 studies within each systematic review (range: 2–111 studies). The full study characteristics are provided in Tables 1–4. Twenty-three reviews analysed axial imaging, nine analysed non-axial imaging, three analysed digital pathology, two analysed waveform data in the form of electrocardiograms (ECG) and fifteen analysed photographic images. Of these photographic images, six analysed endoscopic images, four analysed skin lesions and five analysed fundus photography or optical coherence tomography.

Table 1.

Systematic reviews of artificial intelligence-based diagnostic accuracy studies in axial imaging.

| Author | Specialty | Included studies | Input variables | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nayantara 202046 | Hepatology | 25 | CT | Liver lesions |

| Cho 202011 | Oncology | 12 | MRI | Cerebral metastases |

| Crombé 202047 | Oncology | 52 | CT, CT-PET, MRI, US | Sarcoma |

| Kunze 202048 | Musculoskeletal | 11 | MRI | ACL and/or meniscal tears |

| Groot 202013 | Musculoskeletal | 14 | MRI, X-Rays, US | X-Ray: Fracture detection and/or classification MRI: meniscal/ligament tears, tuberculous vs pyogenic spondylitis US: lateral epicondylitis |

| Steardo Jr 202034 | Psychiatry | 22 | fMRI | Schizophrenia |

| Ninatti 202049 | Oncology | 24 | CT, PET-CT | Molecular therapy targets |

| Ursprung 202010 | Oncology | 57 | CT, MRI | Renal cell carcinoma |

| Halder 202050 | Respiratory Medicine | 45 | CT | Lung nodules |

| Li 201951 | Respiratory Medicine | 26 | CT | Lung nodule detection and/or classification |

| Azer 201952 | Hepatology / Oncology | 11 | CT, MRI, US, Pathology slides | Hepatocellular carcinoma, liver masses |

| Jo 201937 | Neurology | 16 | MRI, PET, CSF | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Moon 201935 | Psychiatry | 43 | sMRI, fMRI | Autism spectrum disorder |

| Sarmento 202053 | Neurology | 8 | CT or MRI | Stroke |

| Filippis 201954 | Psychiatry | 35 | sMRI, fMRI | Schizophrenia |

| Langerhuizen 201914 | Musculoskeletal | 10 | CT, X-Rays | Fracture detection and/or classification |

| Pellegrini 201812 | Neurology | 111 | MRI, CT | Mild cognitive impairment, dementia |

| Pehrson 201955 | Respiratory Medicine | 19 | CT | Lung nodule |

| Bruin 201936 | Psychiatry | 12 | sMRI, fMRI | Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

| McCarthy 201856 | Neurology | 28 | MRI | Frontotemporal dementia |

| Nguyen 201857 | Neurology / Oncology | 8 | MRI | Differentiate glioblastoma and primary CNS lymphoma |

| Senders 201858 | Neurosurgery | 14 | CT, MRI, history, age, gender | Intracranial masses, tumours |

| Smith 201759 | Musculoskeletal | 18 | sMRI, fMRI | Musculoskeletal pain |

Table 4.

Systematic reviews of artificial intelligence-based diagnostic accuracy studies in pathology images.

| Author | Specialty | Included studies | Input variables | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azam 202017 | Pathology | 25 | Histology samples | Varied—dysplasia, malignancy, challenging diagnoses, identification of small objects, miscellaneous |

| Mahmood 202020 | Oncology / ENT/ Maxfax | 11 | Histology samples | Malignant head and neck lesions |

| Azer 201952 | Hepatology / Oncology | 11 | CT, MRI, US, Pathology slides | Hepatocellular carcinoma, liver masses |

The most common AI techniques used within the studies comprising the systematic reviews include support vector machines and artificial neural networks, specifically convolutional neural networks.

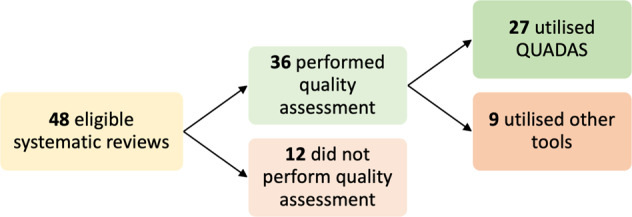

Quality assessment

Thirty-six reviews (75% of studies) undertook a form of quality assessment, of which 27 utilised the QUADAS-2 tool. Further breakdown of quality assessment by study category is detailed below (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Systematic reviews undertaking quality assessment and utilising QUADAS.

QUADAS Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies.

Diagnostic accuracy of AI in axial imaging

Twenty-three systematic reviews comprising 621 studies reported on the application of AI models to diagnostic axial imaging (Table 1). Of the 23 studies, 14 performed quality assessments with 7 reporting use of the QUADAS tool (Table 5). One study utilised RQS and another study utilised the RQS in addition to QUADAS. Other quality assessment tools used include MINORS (n = 3), the Newcastle-Ottawa Score (n = 2) and the Jadad Score (n = 2).

Table 5.

Quality āssessment and adherence to QUADAS in systematic reviews of diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence in axial imaging.

| Study | Modality | Quality assessment | QUADAS | Modifications | Other tools | QUADAS table |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nayantara 202046 | CT | No | – | – | – | – |

| Halder 202050 | CT | No | – | – | – | – |

| Azer 201952 | CT, MRI, US, Pathology slides | No | – | – | – | – |

| Li 201960 | CT | No | – | – | – | – |

| Jo 201937 | MRI, PET, CSF | No | – | – | – | – |

| Sarmento 201953 | CT, MRI | No | – | – | – | – |

| Pehrson 201955 | CT | No | – | – | – | – |

| Bruin 201936 | sMRI, fMRI | No | – | – | – | – |

| Senders 201858 | CT, MRI History/age/gender | No | – | – | – | – |

| Langerhuizen 201914 | X-Rays, CT | Yes | No | Yes—modified MINORS | MINORS | – |

| Smith 201759 | sMRI, fMRI | Yes | No | No | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | – |

| Crombe 202047 | CT, MRI, US | Yes | No | No | Radiomics Quality Score | – |

| Kunze 202048 | MRI | Yes | No | No | MINORS | – |

| Groot 202013 | MRI, X-Rays, US | Yes | No | Yes—modified MINORS | MINORS, TRIPOD | – |

| Steardo Jr 202034 | fMRI | Yes | No | No | Jadad | – |

| Filippis 201954 | sMRI, fMRI | Yes | No | No | Jadad | – |

| Ninatti 202049 | CT, PET-CT | Yes | Yes | No | TRIPOD | Yes |

| Cho 202011 | MRI | Yes | Yes | Yes—modified QUADAS using CLAIM | CLAIM checklist for AI | Yes |

| McCarthy 201856 | MRI | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Moon 201935 | sMRI, fMRI | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Pellegrini 201812 | MRI, CT | Yes | Yes | Yes—only used QUADAS criteria authors deemed applicable | No | Yes |

| Nguyen 201857 | MRI | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes (only for bias) |

| Ursprung 201910 | CT, MRI | Yes | Yes | No | Radiomics Quality Score | Yes (multiple raters; no consensus) |

Out of the seven studies employing QUADAS, five studies completely reported risk of bias and applicability as per the QUADAS guidelines while one study only reported on the risk of bias. One study provided QUADAS ratings given by each of the study authors, but did not provide a consensus table10.

Four studies modified the existing quality assessment tools to improve the suitability and applicability of the tool. Cho et al. tailored the QUADAS tool by applying select signalling questions from CLAIM (Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging)11. Pellegrini and colleagues reported difficulties in finding a suitable quality assessment tool for machine learning diagnostic accuracy reviews and selectively applied items in the QUADAS tool to widen study inclusion12. One study modified the MINORS checklist while another study used a modified version of the MINORS checklist in addition to TRIPOD13,14.

Among the 115 studies across six systematic reviews, the patient selection was deemed to pose the highest or most unclear risk of bias. Fifty-four of 115 studies (47%) were considered to have an unclear risk and 16 studies (14%) were classified as high risk of bias (Fig. 3). A high proportion of studies were also considered to pose an unclear risk in the index test domain. Eighty-one percent of studies had a low risk of bias in the reference standard domain with the remainder representing an unclear risk. Concern regarding applicability was generally low for most studies across all five reviews with 78.5%, 87.9% and 93.5% of studies having low concerns of applicability in the patient selection, index test and reference standard domains, respectively.

Fig. 3. Pie charts demonstrating the risk of bias among axial imaging studies, as assessed through QUADAS.

Low, high and unclear risks are shown for the four QUADAS categories: patient selection, reference standard, index test and flow and timing (panels a, b, c and d, respectively).

Diagnostic accuracy of AI in non-axial imaging

Nine systematic reviews comprising 146 studies reported on the application of AI models to non-axial imaging comprising X-Rays or Ultrasounds (Table 2). Three reviews additionally included studies that also reported on axial imaging.

Table 2.

Systematic reviews of artificial intelligence-based diagnostic accuracy studies in non-axial imaging.

| Author | Specialty | Included studies | Input variables | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li 202060 | Respiratory Medicine | 15 | Chest X-Ray | Pneumonia |

| Xu 202061 | Oncology / Endocrinology | 19 | US | Malignant thyroid nodules |

| Yang 202062 | Musculoskeletal | 9 | X-Rays | Fractures |

| Groot 202013 | Musculoskeletal | 14 | MRI, X-Rays, US | X-Ray: Fracture detection and/or classification MRI: meniscal/ligament tears, tuberculous vs pyogenic spondylitis US: lateral epicondylitis |

| Li 202063 | Oncology | 10 | US | Malignant breast masses |

| Azer 201952 | Hepatology / Oncology | 11 | CT, MRI, US, Pathology slides | Hepatocellular carcinoma, liver masses |

| Harris 201930 | Respiratory Medicine | 53 | Chest X-Ray | Tuberculosis |

| Zhao 201964 | Endocrinology | 5 | Ultrasound | Thyroid nodules |

| Langerhuizen 201914 | Musculoskeletal | 10 | X-Rays, CT | Fracture detection and/or classification |

Of the nine systematic reviews, seven performed quality assessments with five utilising QUADAS (Table 6). The remaining two studies utilised modified versions of the MINORS tools, with one of the studies also utilising TRIPOD as reported under axial imaging.

Table 6.

Quality assessment and adherence to QUADAS in systematic reviews of diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence in non-axial imaging.

| Study | Modality | Quality assessment | QUADAS | Modifications | Other tools | QUADAS table |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li 202060 | Chest X-Ray | No | – | – | – | – |

| Azer 201952 | CT, MRI, US, Pathology slides | No | – | – | – | – |

| Langerhuizen 201914 | X-Rays, CT | Yes | No | Yes | Modified MINORS | – |

| Groot 202013 | MRI, X-Rays, US | Yes | No | Yes (modified MINORS) | TRIPOD + modified MINORS | – |

| Xu 202061 | US | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Yang 202062 | X-Rays | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Li 202060 | US | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Harris 201930 | Chest X-Ray | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Zhao 201964 | US | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

Among the 89 studies across five systematic reviews, the index test domain posed the highest risk of bias while the patient selection domain posed the most unclear risk of bias (Fig. 4). Concern regarding applicability was generally low for most studies across all five reviews with 79.1%, 79.1% and 90.7% of studies having low concerns of applicability in the patient selection, index test and reference standard domains, respectively.

Fig. 4. Pie charts demonstrating the risk of bias among non-axial imaging studies, as assessed through QUADAS.

Low, high and unclear risks are shown for the four QUADAS categories: patient selection, reference standard, index test and flow and timing (panels a, b, c and d, respectively).

Diagnostic accuracy of AI in photographic images

Fifteen systematic reviews comprising 316 studies reported on the application of AI to photo-based diagnostics (Table 3). This consisted of images of skin lesions (n = 4), endoscopic images (n = 6) and fundus photography or optical coherence tomography (n = 5).

Table 3.

Systematic reviews of artificial intelligence-based diagnostic accuracy studies in photographic images.

| Author | Specialty | Included studies | Input variables | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bang 202065 | Gastroenterology | 8 | Endoscopic images | H. Pylori infection |

| Mohan 202066 | Gastroenterology | 9 | Endoscopic images | Gastrointestinal ulcers/haemorrhage |

| Hassan 202067 | Gastroenterology | 5 | Colonoscopic images | Polyps |

| Lui 202068 | Gastroenterology | 18 | Colonoscopy images | Polyps |

| Lui 202069 | Gastroenterology | 23 | Endoscopic images | Neoplastic lesions, Barrett’s oesophagus, squamous oesophagus, H. Pylori status |

| Wang 202070 | Ophthalmology | 24 | Fundus photography | Diabetic Retinopathy |

| Soffer 202071 | Gastroenterology | 10 | Wireless Capsule Endoscopic images | Detection of ulcers, polyps, bleeding, angioectasia |

| Islam 202072 | Ophthalmology | 31 | Fundus photography | Retinal vessel segmentation |

| Islam 202073 | Ophthalmology | 23 | Fundus photography | Diabetic retinopathy |

| Murtagh 202074 | Ophthalmology | 23 | OCT, Fundus photography | Glaucoma |

| Nielsen 201975 | Ophthalmology | 11 | Fundus photography | Diabetic Retinopathy |

| Marka 201938 | Dermatology / Oncology | 39 | Images of skin lesions | Non-melanoma skin cancer |

| Ruffano 201815 | Dermatology / Oncology | 42 | Images of skin lesions | Non-melanoma skin cancer |

| Chuchu 201816 | Dermatology / Oncology | 2 | Images of skin lesions | Melanoma |

| Rajpara 200976 | Dermatology / Oncology | 30 | Images of skin lesions | Melanoma |

Of the 15 systematic reviews, 13 performed quality assessments with 11 utilising QUADAS (Table 7). One study did not report any details on QUADAS while another did not report on applicability concerns and only risk of bias. The remaining two studies utilised the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool and modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. In addition, Ruffano et al. and Chuchu et al. adapted the QUADAS tool specifically for non-melanoma skin cancer and melanoma respectively with definitions and thresholds specified by consensus for low and high risk for bias15,16.

Table 7.

Quality assessment and adherence to QUADAS in systematic reviews of diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence in photographic images.

| Study | Modality | Quality assessment | QUADAS | Modifications | Other tools | QUADAS table |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohan 202066 | Endoscopic images | No | – | – | – | – |

| Rajpara 200976 | Images of skin lesions | No | – | – | – | – |

| Hassan 202067 | Real-time computer-aided detection colonoscopy | Yes | No | No | Cochrane Risk Bias Tool | – |

| Murtagh 202074 | OCT/Fundus photography | Yes | No | Yes—modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | – |

| Bang 202065 | Endoscopic images | Yes | Yes | No | – | Yes |

| Lui 202068 | Endoscopic images | Yes | Yes | No | – | Yes |

| Wang 202070 | Fundus photography | Yes | Yes | No | – | Yes |

| Soffer 202071 | Wireless capsule endoscopy | Yes | Yes | No | – | Yes - but not for applicability |

| Islam 202072 | Fundus photography | Yes | Yes | No | – | Yes |

| Lui 202069 | Colonoscopy | Yes | Yes | No | – | Yes |

| Islam 202073 | Fundus photography | Yes | Yes | No | – | Yes |

| Nielsen 201975 | Fundus photography | Yes | Yes | No | – | Yes |

| Marka 201938 | Images of skin lesions | Yes | Yes | No | – | Yes |

| Ruffano 201815 | Images of skin lesions | Yes | Yes | Yes—modified for non-melanoma skin cancers | – | Yes |

| Chuchu 201816 | Images of skin lesions | Yes | Yes | Yes—modified for melanoma | – | Yes |

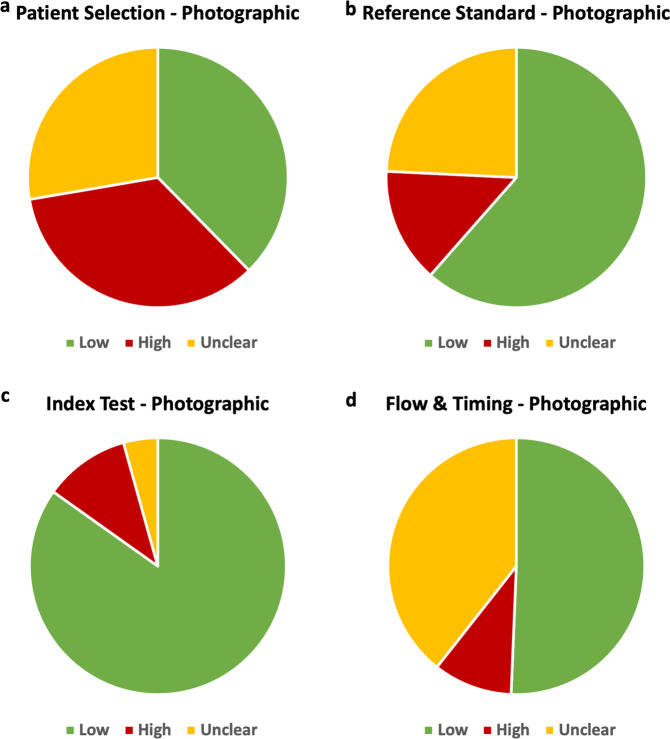

Among the 231 studies across 11 systematic reviews, the patient selection domain contained the highest risk of bias while the flow and timing domain posed the most unclear risk of bias (Fig. 5). Concern regarding applicability was high or unclear in the patient selection domain for the majority of studies with 54.8% of studies reporting high or unclear applicability concerns. Concerns of applicability were lower in the index test and reference standard domain with 67.5% of studies reporting low concerns in the index test domain and 53.8% in the reference standard domain.

Fig. 5. Pie charts demonstrating the risk of bias among photographic images studies, as assessed through QUADAS.

Low, high and unclear risks are shown for the four QUADAS categories: patient selection, reference standard, index test and flow and timing (panels a, b, c and d, respectively).

Diagnostic accuracy of AI in pathology

Three systematic reviews comprising 47 studies reported on the application of AI to pathology. One review examined pathology slides in addition to imaging (Table 4).

Two reviews performed quality assessment utilising QUADAS (Table 8). Mahmood et al. used a tailored QUADAS-2 tool. Only one review provided a tabular display of QUADAS assessment in the recommended format17 and reported low risk of bias among the majority of included studies across all domains (Patient Selection: 64% of studies low risk; Index Test: 80% low risk; Reference Standard: 92% low risk; Flow and Timing: 84% low risk) and low concerns regarding applicability.

Table 8.

Quality āssessment and adherence to QUADAS in systematic reviews of diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence in pathology.

Diagnostic accuracy of AI in waveform data

Two systematic reviews comprising 44 primary studies reported on AI algorithms to diagnose pathology from ECGs18,19 (Table 9). Both utilised QUADAS-2 and adhered to reporting standards. The risk of bias was low across the majority of included studies with no studies classed a high risk of bias in the patient selection or reference standard domain. Two studies in the index test domain and one study in the flow and timing domain were deemed high risk.

Table 9.

Quality āssessment and adherence to QUADAS in systematic reviews of diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence in waveform data.

Perceived limitations

Thirteen studies reported an inability to provide systematic quality assessment or evaluate certain biases as a limitation in their study (Supplementary Fig. 1). Specifically, these included concerns around size and quality of the dataset, including its real-world clinical applicability; for example including a whole tissue section instead of the portion of interest only20 and providing samples from multiple centres across different demographic populations to improve the generalisability of the model. Appropriate separation of a dataset into training, validation and test sets without overlap was also highlighted as an area needing evaluation, as an overlap between datasets would lead to higher accuracy rates. Eight reviews modified or tailored pre-existing quality assessment tools to customise it to the methodologies and types of studies as reported above.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that rigorous quality assessment and evaluation of the risk of bias is not consistently carried out in secondary research of AI-based diagnostic accuracy studies. Although considered an essential requirement in secondary research, only 75% of reviews completed quality appraisal, with 56% of papers utilising QUADAS. Although it remains the predominant quality assessment method in this field, the varied use of both new and modified tools (e.g. RQS tool) suggests that the current instruments may not address all the quality appraisal considerations for AI-centred diagnostic accuracy studies. While the primary aim of this paper was to determine adherence to QUADAS guidelines, we also sought to gain a deeper understanding of the reasons behind low adherence to QUADAS in its current form in AI studies. To achieve clinical utility and generalisability, these studies must include data that bears resemblance to the interplay of numerous phenotypical differences contributing to the outcome and adequately reflects the population.

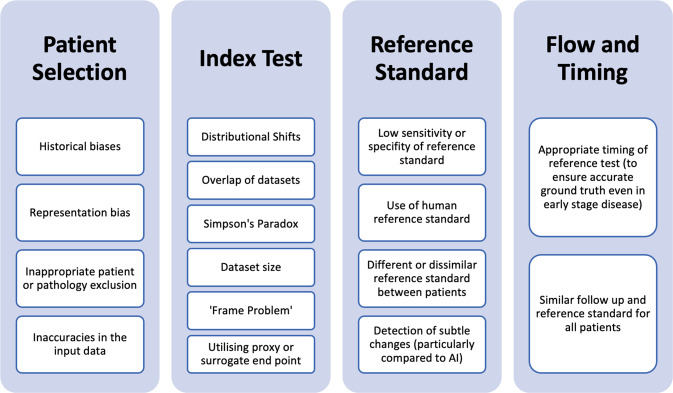

In the patient selection domain, 113 studies (26.7% of studies) were deemed high risk and an additional 30.7% of studies were deemed to be of unclear risk of bias. This risk was greatest in studies reporting on photographic images, where 35% of studies were at high risk of bias (Table 10). Factors leading to a high risk of bias in patient selection include poor patient sampling technique and inappropriate exclusion of data on a patient or feature level. As AI algorithms rely on previously seen data to identify patterns and generate results, inaccuracies and biases in input data can be perpetuated and augmented by the model and under-representation of certain factors or demographics may result in inferior algorithm performance21. Inappropriate representation of patient demographics or socioeconomic factors may also manifest in the algorithm output as discriminate results. This type of bias may be aggravated in photographic images where utilising data from a specific demographic may create blind spots in the AI algorithm, thus amplifying racial biases22. For example, employing an AI model to detect dermatological abnormalities on dark skin resulted in higher rates of missed diagnoses further increasing the disparity in diagnosis23,24. In addition to a lack of diversity within the input data, there are several other sources of AI-specific biases including historical bias, representation bias, evaluation bias, aggregation bias, population bias and sampling bias which are discussed in detail by Mehrabi et al. and Simpson’s Paradox (Fig. 6)25. Although these biases can be present in research employing traditional statistical methodologies, they may be exaggerated in AI-based tools due to the reliance on existing data. Additionally, there are factors contributing to heterogeneity in images including those related to manufacturer-based specifics for image capture, recording, presentation and the reading platform. These biases and sources of heterogeneity in AI research are also highlighted within some of the included systematic reviews as limitations to the adequate analysis.

Table 10.

Summary of risk of bias across the QUADAS domains.

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axial imaging |

14% high risk 47% unclear |

12% high risk 49% unclear |

0% high risk 19% unclear |

3% high risk 17% unclear |

| Non-axial imaging |

29% high risk 19% unclear |

37% high risk 7% unclear |

45% high risk 7% unclear |

11% high risk 10% unclear |

| Photographic images |

35% high risk 28% unclear |

11% high risk 4% unclear |

24% high risk 14% unclear |

39% high risk 10% unclear |

| Pathology |

28% high risk 8% unclear |

8% high risk 12% unclear |

8% high risk 0% unclear |

16% high risk 0% unclear |

| Waveform data |

0% high risk 32% unclear |

5% high risk 5% unclear |

0% high risk 27% unclear |

2% high risk 25% unclear |

Fig. 6. Types of biases affecting quality and applicability of artificial intelligence-based diagnostic accuracy studies.

Biases are listed under the QUADAS domain they primarily affect.

The creation of AI diagnostic models requires high-quality datasets, which emulate real-world clinical scenarios to ensure accurate and generalisable outcomes. Consequently, unjustified patient exclusion or inappropriate feature selection may overestimate the diagnostic accuracy of the AI model and increase bias. Exclusion of conditions with overlapping traits to the diagnosis being studied may also skew the results and produce inaccurately higher diagnostic accuracy rates, leading to low clinical utility. For example, excluding all inflammatory pathologies of the bowel when developing an AI tool for polyp detection reduces the algorithm’s ability to discriminate between benign polyps and more serious pathologies in a real-world setting (where patients attend a clinical review with a myriad of underlying pathologies)26. Similarly, excluding blurry or out-of-focus images may lead to falsely elevated diagnostic accuracy and is not reflective of real-world situations, thereby reducing clinical value. Finally, in comparison to conventional index tests which require a description of sampling methods on a patient only, AI models also require the description of sampling input level data27; insufficient description of this may have led to considerable studies presenting an unclear risk of bias.

Within the index test domain, both axial and non-axial imaging studies demonstrated a high risk of bias. This domain pertains to the development and validation of the AI algorithm and interpretation of the generated output. First, distributional shifts between the training, validation and testing datasets can result in the algorithm producing incorrect results with confidence. These shifts can also lead to inaccurate conclusions about the precision of the algorithm if the algorithm is tested inappropriately on a patient cohort for which it was not trained28. Second, overlapping datasets can overestimate diagnostic accuracy in comparison to using external validation data. Third, given the heterogenous nature of large datasets necessary for AI, there is an increased possibility of confounding factors amongst the data. If the model does not appropriately address causal relations between different factors, this can lead to Simpson’s Paradox, which arises when inferences are made from aggregated analysis of heterogenous data comprised of multiple subgroups onto individual subgroups. Separating the dataset into different groups based on confounding variables provides a different result compared to analysing all the data together25. Finally, the size of the dataset is particularly important for AI models as smaller datasets may provide lower diagnostic accuracy and result in poor generalisability29. Additionally, if the AI is not trained on all the varied presentations of a condition, straightforward diagnoses may not be detected by the algorithm, a flaw also known as the ‘Frame Problem’. Specific signalling questions addressing these potential areas of concern may be useful in identifying and characterising potential sources of bias and determining model generalisability.

Forty-eight studies (11.4%) posed a high risk of bias in the reference standard domain. Though non-axial imaging studies appeared to be disproportionately at higher risk of bias in this domain, all studies resulted from one systematic review30. Although overall low risk, this domain contains several potential sources of bias for AI-specific studies of diagnostic accuracy. Determination of an appropriate reference standard or ‘ground truth’ for training models requires consideration of the best available evidence and may involve amalgamating clinical, radiological and laboratory data29. Comparison of AI against a human reference standard may be utilised, although should be avoided as a sole reference standard if an alternative test providing higher sensitivity and specificity is feasible. For example, 32 of 33 studies in Harris et al. were at high risk of bias due to the reference standard comprising human interpretation of the chest X-ray without the use of sputum culture confirmation30. When utilising a human reference standard, the number and experience of operators and presence of interobserver variability should be clearly detailed. Ideally, the reference standard should include multiple annotations from different experts to reduce subjectivity and account for interobserver variability20. This is particularly important in the context of AI given its potential capabilities in detecting disease more accurately than human operators and identifying subtle changes or patterns not detectable by human operators1,31–33. In the case of models pertaining to early disease detection, a reference standard comprising a combination of investigations including repeat tests at varying time points may be required.

Finally, the domain covering flow and timing evaluated the time between the reference standard and index test, parity of reference standard assessment amongst all participants and inappropriate exclusion of study patients from the final study results. Within this domain, studies performed reasonably well with only 37 studies (8.8%) recorded as high risk of bias. However, methodologies relating to study flow and standards of timing vary in AI-based studies representing a different risk of bias. For example, neuropsychiatric studies utilising AI have been able to detect the presence of early cognitive changes or aid the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders through identification of otherwise indiscernible changes in structural or functional neuroimaging34–36. In mild or initial stages of the disease, AI may actually be more discriminant than the reference standard in identifying early variations or subtle patterns34,37. Therefore, the timing of the reference standard in relation to the index test is imperative and may need to be scheduled at a later date to ensure the diagnosis reflected by the reference standard is accurate. Furthermore, variation in reference standards used in positive cases compared to negative cases may cause issues when determining the diagnostic accuracy of AI models. For example, histopathology results may be used to diagnose malignancy but performing a biopsy on obviously non-cancerous lesions presents ethical concerns; and as a result, less invasive but potentially less accurate confirmatory reference standard tests are utilised instead38. However, using reference standards that significantly vary in accuracy, such as clinical follow-up only in contrast to tissue diagnosis may cause verification bias i.e. false negatives may actually be classed as true negatives and inflate estimates of accuracy. In these cases where an alternative reference standard is required, utilising an investigation with high negative predictive value such as clinical follow-up with a PET scan to rule out malignancy may be suitable39. However, in AI-based studies, additional considerations have to be given for similarities between the ground truth used to train the model and the reference standard used to validate and test the model. If there are considerable disparities between the two, the model may be erroneously deemed inadequate.

Perceived limitations of current quality assessment tools highlight the need for an AI-specific guideline to evaluate diagnostic accuracy studies. Algorithm and input data quality, real-world clinical applicability and algorithm generalisability are important sources of bias that need to be addressed in an adapted AI-specific tool. Quality assessment tools similar to QUADAS are currently being modified to match the evolving landscape of research. For example, STARD (Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies), is currently being extended to develop the STARD-AI guidelines to specifically appraise AI-based diagnostic accuracy studies27. Additionally, AI extensions to TRIPOD (Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis) and CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) have been published, and SPIRIT-AI (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) is in progress40–42. While our main message is demonstrating a lack of adherence to QUADAS, the heterogeneity seen amongst the studies highlights the confusion on how to best report studies of diagnostic accuracy in AI. This suggests a need to generate a new checklist, which can accommodate AI-specific needs and the changing paradigm of research in a digitally driven world.

This review demonstrates the incomplete uptake of quality assessment tools in AI-centred diagnostic accuracy reviews and highlights variations in AI-specific methodological aspects and reporting across all domains of QUADAS in particular. These factors include generalisability and diversity in patient selection, development of training, validation and testing datasets, as well as definition and evaluation of an appropriate reference standard. When evaluating study quality, potential biases and applicability of AI diagnostic accuracy studies, it is imperative that systematic reviews consider these factors. Whilst the QUADAS-2 tool explicitly recognises the difficulty in developing a tool generalisable to all studies across all specialties and topics and proposes the author modifies the signalling questions as needed, it is essential to further define these questions for AI studies given complexities in methodology. Given the complexities of implementing such tools in practice, it is imperative to have robust tools to evaluate these AI tools to ensure high diagnostic value and seamless translation into a clinical setting43.

We propose the creation of a QUADAS-AI extension emulating the successful development of AI extensions to other quality assessment tools27,40,41. QUADAS-AI and STARD-AI may be employed in parallel to harmonise the evaluation of diagnostic accuracy studies. The adoption of a robust and accepted instrument to assess the quality of primary diagnostic accuracy AI studies for integration within a systematic review can offer an evidence-base to safely translate AI tools into a real-world setting that can empower clinicians, industry, policymakers and patients to maximise the benefits of AI for the future of medical diagnostics and care.

Methods

Search strategy

An electronic search was conducted for studies in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to identify systematic reviews reporting on diagnostic accuracy studies in AI studies (Fig. 1)44. MEDLINE and Embase were systematically searched from January 2000 to December 2020. The search strategy was developed through discussion with experts in healthcare AI and research methodology. A mixture of keywords and MeSH terms were used together with appropriate Boolean operators (Supplementary Table 1). Reference lists of included papers were investigated to identify further studies.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts for initial inclusion. Studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) systematic review (2) reporting on AI studies pertaining to diagnostic accuracy. Commentary articles, conference extracts and narrative reviews were excluded. Studies either examining prognostication or reporting on AI/machine learning (ML) to predict the presence of disease were also excluded. Specifically, diagnostic accuracy studies were defined as research evaluating the ability of a tool to evaluate the current presence or absence of a particular pathology, in contrast to prognostication or prediction studies, which forecast an outcome or likelihood of a future diagnosis. Two reviewers (SJ and VS) independently screened titles and abstracts for potential inclusion. All potential abstracts were subjected to full-text review by two independent reviewers. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third independent reviewer (HA).

Data extraction

Data were extracted onto a standardised proforma by two independent reviewers (VS and SJ). Study characteristics extracted were study author, year, institution, country, journal and journal impact factor. Key AI-related extraction items were identified through examination of recently developed AI extensions to existing quality assessment tools. A consensus was reached amongst authors to ascertain vital items for data extraction including use of QUADAS-2 and/or other quality assessment tools, quality assessment tool adherence, risk of bias within individual studies, modifications to pre-existing tools, use of multiple tools to improve applicability to AI-specific studies and any limitations pertaining to quality assessment expressed by study authors.

Studies were classified into five clinical categories based upon the type of sample evaluated and upon the diagnostic task: (a) axial medical imaging, (b) non-axial medical imaging, (c) histopathological digital records (digital pathology) (d) photographic images and (e) physiological signals.

Quality assessment

The AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) was employed to evaluate the quality of included studies (Supplementary Table 2)45.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

H.A. and V.S. conceived the project. S.J. and V.S. performed the literature search, data extraction and data analysis. S.J. and V.S. drafted the manuscript. H.A., P.N., L.H. and S.R.M. edited the manuscript. H.A. and A.D. supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. S.J. and V.S. contributed equally to this work.

Funding

Infrastructure support for this research was provided by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Center (BRC).

Data availability

The authors declare that all data included in the results of this study are available within the paper and the Supplementary files.

Competing interests

HA and AD: HA is Chief Scientific Officer, Preemptive Medicine and Health Security, Flagship Pioneering, AD is Executive Chairman of Preemptive Medicine and Health Security, Flagship Pioneering.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Shruti Jayakumar, Viknesh Sounderajah.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41746-021-00544-y.

References

- 1.McKinney SM, et al. International evaluation of an AI system for breast cancer screening. Nature. 2020;577:89–94. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Fauw J, et al. Clinically applicable deep learning for diagnosis and referral in retinal disease. Nat. Med. 2018;24:1342–1350. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamada M, et al. Development of a real-time endoscopic image diagnosis support system using deep learning technology in colonoscopy. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagpal K, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for improving Gleason scoring of prostate cancer. npj Digit. Med. 2019;2:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0112-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiting P, Rutjes AWS, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PMM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: A tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2003;3:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whiting PF, et al. Quadas-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambin P, et al. Radiomics: The bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2017;14:749–762. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank RA, et al. Are Study and Journal Characteristics Reliable Indicators of “Truth” in Imaging Research? Radiology. 2018;287:215–223. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo C, et al. Challenges for the evaluation of digital health solutions—A call for innovative evidence generation approaches. npj Digit. Med. 2020;3:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41746-020-00314-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ursprung S, et al. Radiomics of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in renal cell carcinoma—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2020;30:3558–3566. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06666-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho, S. J. et al. Brain metastasis detection using machine learning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuro. Oncol. 1–12, 10.1093/neuonc/noaa232 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Pellegrini E, et al. Machine learning of neuroimaging for assisted diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagnosis, Assess. Dis. Monit. 2018;10:519–535. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groot OQ, et al. Does Artificial Intelligence Outperform Natural Intelligence in Interpreting Musculoskeletal Radiological Studies? A Systematic Review. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2020;478:2751–2764. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langerhuizen DWG, et al. What Are the Applications and Limitations of Artificial Intelligence for Fracture Detection and Classification in Orthopaedic Trauma Imaging? A Systematic Review. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2019;477:2482–2491. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruffano, L. et al. Computer-assisted diagnosis techniques (dermoscopy and spectroscopy-based) for diagnosing skin cancer in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.2018, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Chuchu, N. et al. Smartphone applications for triaging adults with skin lesions that are suspicious for melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.2018, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Azam AS, et al. Diagnostic concordance and discordance in digital pathology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020;0:1–8. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iannattone PA, Zhao X, VanHouten J, Garg A, Huynh T. Artificial Intelligence for Diagnosis of Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Meta-analysis of Machine Learning Approaches. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020;36:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sprockel J, Tejeda M, Yate J, Diaztagle J, González E. Intelligent systems tools in the diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes: A systemic review. Arch. Cardiol. Mex. 2018;88:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.acmx.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahmood H, et al. Use of artificial intelligence in diagnosis of head and neck precancerous and cancerous lesions: A systematic review. Oral. Oncol. 2020;110:104885. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larrazabal AJ, Nieto N, Peterson V, Milone DH, Ferrante E. Gender imbalance in medical imaging datasets produces biased classifiers for computer-aided diagnosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:12592–12594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919012117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly CJ, Karthikesalingam A, Suleyman M, Corrado G, King D. Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Medicine. 2019;17:195. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1426-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamulegeya, L. H. et al. Using artificial intelligence on dermatology conditions in Uganda: A case for diversity in training data sets for machine learning. bioRxiv 826057, 10.1101/826057 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Adamson AS, Smith A. Machine learning and health care disparities in dermatology. JAMA Dermatology. 2018;154:1247–1248. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehrabi N, Morstatter F, Saxena N, Lerman K, Galstyan A. A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021;54:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross S, et al. Computer-based classification of small colorectal polyps by using narrow-band imaging with optical magnification. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011;74:1354–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sounderajah V, et al. Developing specific reporting guidelines for diagnostic accuracy studies assessing AI interventions: The STARD-AI Steering Group. Nat. Med. 2020;26:807–808. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0941-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Challen R, et al. BMJ Qual Artificial intelligence, bias and clinical safety. Saf. 2019;28:231–237. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willemink MJ, et al. Preparing medical imaging data for machine learning. Radiology. 2020;295:4–15. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020192224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris M, et al. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence-based computer programs to analyze chest x-rays for pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0221339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck AH, et al. Imaging: Systematic analysis of breast cancer morphology uncovers stromal features associated with survival. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:108ra113. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poplin R, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular risk factors from retinal fundus photographs via deep learning. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018;2:158–164. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Attia ZI, et al. An artificial intelligence-enabled ECG algorithm for the identification of patients with atrial fibrillation during sinus rhythm: a retrospective analysis of outcome prediction. Lancet. 2019;394:861–867. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31721-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steardo L, et al. Application of Support Vector Machine on fMRI Data as Biomarkers in Schizophrenia Diagnosis: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11:588. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moon SJ, Hwang J, Kana R, Torous J, Kim JW. Accuracy of Machine Learning Algorithms for the Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Studies. JMIR Ment. Heal. 2019;6:e14108. doi: 10.2196/14108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruin W, Denys D, van Wingen G. Diagnostic neuroimaging markers of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Initial evidence from structural and functional MRI studies. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2019;91:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jo T, Nho K, Saykin AJ. Deep Learning in Alzheimer’s Disease: Diagnostic Classification and Prognostic Prediction Using Neuroimaging Data. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:220. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marka A, Carter JB, Toto E, Hassanpour S. Automated detection of nonmelanoma skin cancer using digital images: A systematic review. BMC Med. Imaging. 2019;19:21. doi: 10.1186/s12880-019-0307-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reitsma JB, Rutjes AWS, Khan KS, Coomarasamy A, Bossuyt PM. A review of solutions for diagnostic accuracy studies with an imperfect or missing reference standard. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62:797–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu X, Cruz Rivera S, Moher D, Calvert MJ, Denniston AK. Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the CONSORT-AI extension. Nat. med. 2020;26:1364–1374. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1034-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins GS, Moons KGM. Reporting of artificial intelligence prediction models. The Lancet. 2019;393:1577–1579. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cruz Rivera S, et al. Guidelines for clinical trial protocols for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the SPIRIT-AI extension. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1351–1363. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1037-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray E, et al. Evaluating Digital Health Interventions: Key Questions and Approaches. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016;51:843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ (Online) 2009;339:332–336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shea, B. J. et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ358, j4008 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Nayantara, P. V., Kamath, S., Manjunath, K. N. & Rajagopal, K. V. Computer-aided diagnosis of liver lesions using CT images: A systematic review. Comput. Bio. Med.127 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Crombé, A. et al. Systematic review of sarcomas radiomics studies: Bridging the gap between concepts and clinical applications? Eur. J. Radiol. 132, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Kunze KN, et al. Diagnostic Performance of Artificial Intelligence for Detection of Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Meniscus Tears: A Systematic Review. Arthrosco. - J. Arthrosco. Related Sur. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2020.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ninatti, G., Kirienko, M., Neri, E., Sollini, M. & Chiti, A. Imaging-based prediction of molecular therapy targets in NSCLC by radiogenomics and AI approaches: A systematic review. Diagnostics10, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Halder A, Dey D, Sadhu AK. Lung Nodule Detection from Feature Engineering to Deep Learning in Thoracic CT Images: a Comprehensive Review. J. Digit. Imaging. 2020;33:655–677. doi: 10.1007/s10278-020-00320-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li, D. et al. The performance of deep learning algorithms on automatic pulmonary nodule detection and classification tested on different datasets that are not derived from LIDC-IDRI: A systematic review. Diagnostics9, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Azer SA. Deep learning with convolutional neural networks for identification of liver masses and hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review. World J. of Gastroi. Oncol. 2019;11:1218–1230. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i12.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarmento, R. M., Vasconcelos, F. F. X., Filho, P. P. R., Wu, W. & De Albuquerque, V. H. C. Automatic Neuroimage Processing and Analysis in Stroke - A Systematic Review. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 13, 130–155 (2020).. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.De Filippis R, et al. Machine learning techniques in a structural and functional MRI diagnostic approach in schizophrenia: A systematic review. Neuropsychiat DisTreat. 2019;15:1605–1627. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S202418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pehrson, L. M., Nielsen, M. B. & Lauridsen, C. A. Automatic pulmonary nodule detection applying deep learning or machine learning algorithms to the LIDC-IDRI database: A systematic review. Diagnostics9, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.McCarthy J, Collins DL, Ducharme S. Morphometric MRI as a diagnostic biomarker of frontotemporal dementia: A systematic review to determine clinical applicability. NeuroImage Clin. 2018;20:685–696. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nguyen AV, Blears EE, Ross E, Lall RR, Ortega-Barnett J. Machine learning applications for the differentiation of primary central nervous system lymphoma from glioblastoma on imaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Focus. 2018;45:E5. doi: 10.3171/2018.8.FOCUS18325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Senders JT, et al. Natural and artificial intelligence in neurosurgery: A systematic review. Clin. Neurosurg. 2018;83:181–192. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith A, López-Solà M, McMahon K, Pedler A, Sterling M. Multivariate pattern analysis utilizing structural or functional MRI—In individuals with musculoskeletal pain and healthy controls: A systematic review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:418–431. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li, Y., Zhang, Z., Dai, C., Dong, Q. & Badrigilan, S. Accuracy of deep learning for automated detection of pneumonia using chest X-Ray images: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Comput. Bio. Med.123, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Xu L, et al. Computer-Aided Diagnosis Systems in Diagnosing Malignant Thyroid Nodules on Ultrasonography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Thyroid J. 2020;9:186–193. doi: 10.1159/000504390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of deep learning in orthopaedic fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Radiol. 2020;75:713.e17–713.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li J, et al. The value of S-Detect for the differential diagnosis of breast masses on ultrasound: a systematic review and pooled meta-analysis. Med. Ultrason. 2020;22:211. doi: 10.11152/mu-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao, W. J. et al. Effectiveness evaluation of computer-aided diagnosis system for the diagnosis of thyroid nodules on ultrasound: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (United States)98, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Bang, C. S., Lee, J. J. & Baik, G. H. Artificial intelligence for the prediction of helicobacter pylori infection in endoscopic images: Systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. J. Med. Inter. Res.22, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Mohan BP, et al. High pooled performance of convolutional neural networks in computer-aided diagnosis of GI ulcers and/or hemorrhage on wireless capsule endoscopy images: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020;93:356–364.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hassan C, et al. Performance of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021;93:77–85.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lui TKL, Guo CG, Leung WK. Accuracy of artificial intelligence on histology prediction and detection of colorectal polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020;92:11–22.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lui TKL, Tsui VWM, Leung WK. Accuracy of artificial intelligence–assisted detection of upper GI lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020;92:821–830.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang S, et al. Performance of deep neural network-based artificial intelligence method in diabetic retinopathy screening: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. Eur. J. Endocrin. 2020;183:41–49. doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Soffer S, et al. Deep learning for wireless capsule endoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020;92:831–839.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Islam, M. M., Yang, H. C., Poly, T. N., Jian, W. S. & (Jack) Li, Y. C. Deep learning algorithms for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Comput. Meth. Prog. Biomed. 191, 105320 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Islam MM, Poly TN, Walther BA, Yang HC, Li Y-C. (Jack). Artificial Intelligence in Ophthalmology: A Meta-Analysis of Deep Learning Models for Retinal Vessels Segmentation. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:1018. doi: 10.3390/jcm9041018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Murtagh P, Greene G, O’Brien C. Current applications of machine learning in the screening and diagnosis of glaucoma: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2020;13:149–162. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2020.01.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nielsen KB, Lautrup ML, Andersen JKH, Savarimuthu TR, Grauslund J. Deep Learning–Based Algorithms in Screening of Diabetic Retinopathy: A Systematic Review of Diagnostic Performance. Ophthalmol. Retina. 2019;3:294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rajpara SM, Botello AP, Townend J, Ormerod AD. Systematic review of dermoscopy and digital dermoscopy/ artificial intelligence for the diagnosis of melanoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2009;161:591–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data included in the results of this study are available within the paper and the Supplementary files.