Abstract

Nurses’ turnover is a major global problem with significant service and cost implications. Although sizeable research inquiries have been made into the antecedents, the dynamics, and the consequences of nurses’ turnover, there is still a lack of fine-grained understanding of the psychological states that reflect the cumulative impact of different antecedents and immediately precede nurses’ intentions to quit either from their unit/organization and/or their profession. This paper introduces and develops a meaning-based view of nurses’ turnover. This perspective distinguishes between meaning in work (based on the nurses’ relationship with their work) and meaning at work (based on the nurses’ relationship with their work environment) and explain the implications of high/low meaning in and at work on nurses’ turnover. This meaning-based view of nurses’ turnover offers nurses, administrators and policy makers a deeper and a more nuanced understanding of turnover and promises more tailored remedies for the turnover problem.

Keywords: meaning at work, meaning-based view of nurses’ turnover, meaning in work, nurses' turnover

Introduction

Healthcare organizations around the world face growing pressures to provide high quality services, to a greater number of clients, at lower costs. 1 This three-pronged demand, emphasizing quality, volume and costs, stems from the convergence of several forces, which include an aging population with greater healthcare needs, tight budgets and competing priorities (especially for government funded healthcare services), chronic understaffing of medical professionals, and greater scrutiny in a litigation-prone societal and regulatory context. In such a context, nurses are at the forefront of having to cope with the net impact of these combined forces, i.e., the onus falls on them for the day to day operationalization of the lofty expectations and aspirations of the stakeholders in healthcare. For nurses, the prolonged exposure to life or death situations, the demand and the intensity of work, the mental and the emotional demands of their work, and the pressure to build and maintain supportive relationships is relentless. As a result, it is becoming increasingly common to see nurses experience undesirable personal outcomes, ranging from exhaustion and burnout to absenteeism and turnover.

Nurses’ turnover is a troubling issue and a major problem that adversely impacts the health care system in many ways. Estimates from different countries point to annual turnover rates being stubbornly high – around 9.4% in England and Wales, 2 14% in the U.S., 3 and close to 27% in Canada (compared to turnover rates of 7.3% in the general population). 4 In addition, the service and cost implications are significant (e.g., cost of replacing a nurse can range up to $50,000) 5 and high nurses’ turnover has been associated with lower job satisfaction, higher probability of medical errors, increased overtime hours, role conflict in the unit, and prolonged length of stay of clients. 5

All of these highlight the urgency of reducing such high turnover. 6 Not surprisingly, prior research efforts have delved into exploring the antecedents, dynamics, and consequences of turnover. But there is a paucity of fine-grained research regarding the conditions under which nurses quit their unit/organization versus their profession. This distinction is key not just for the differing implications it has for the impact on service quality and costs, but also for the remedies necessary to address turnover. The few studies to date on this specific question offer some early insights but stop short of offering a strong theoretical frame to accommodate the different findings and serve as a platform for a program of research. Drawing from the meaningfulness of work literature, this paper offers nurses, administrators and policy makers a model that sheds light on the nuances in nurses’ turnover and suggests that understanding the type of turnover may help to find the appropriate remedy.

An overview of the literature on nurses’ turnover

The literature on nurses’ turnover can be organized into three clusters: antecedents of turnover, perspectives on turnover, and types of turnover.

Cluster 1: Antecedents of turnover

Prior research has identified a range of factors that impact nurses’ turnover7–11 which are contextual, attitudinal or demographic in nature. The contextual (organizational and job) antecedents include job routinization, autonomy, organizational and social support, distributive justice, career development, and pay; the attitudinal factors cover job satisfaction, stress, commitment, and affectivity; and the demographic factors are age, education level, rank and tenure. Of these different factors, the more significant antecedents appear to be distributive justice, workload, resource inadequacy, supervisory support, kinship/network support, commitment, job satisfaction, and intention to leave.7–11 In exploring the factors that need to be addressed to reduce voluntary turnover among nurses, Rondeau and Wagar 6 found that the embracing a quality-of-work-life Human Resource Management (HRM) employment system (employee-centered and family-friendly practices) and a high-involvement HRM work system (workplace arrangements that encourage commitment, engagement, accountability and participation) have a positive impact. In a similar vein, Hwang and Park 12 found that nurses who perceive a positive ethical climate regarding patients, managers, physicians, and the hospital (place of work) are more likely to remain in the organization. Missing, however, from this collection of studies is an understanding of how the different antecedents impact nurses’ turnover, i.e., the factors that mediate between the antecedents and intentions to quit.

Cluster 2: Perspectives on turnover

Nurses’ turnover has also been studied from several perspectives or theoretical lenses that cast a more holistic light on the turnover dynamics. The description below is not meant to be an exhaustive review but a brief summation of some of the more interesting theoretical perspectives. These perspectives vary in their orientation from cognitive (e.g., psychological significance, reasoned action), to affective (e.g., emotional labor, burnout), to exchange (e.g., social exchange, demands and resources), to systems (e.g., systems, multidisciplinary).

Adopting a cognitive perspective, Takase 13 proposed a multi-stage model of nurses’ turnover centered around the psychological significance that nurses attribute to the different factors they encounter at work. In other words, the relationship between the factors nurses encounter at work and turnover intention is mediated by psychological significance, and that turnover intention becomes progressively serious (i.e., it starts with withdrawal behavior which manifests itself in a lack of enthusiasm on the job, absenteeism, and search for an alternate job). Prestholdt 14 used a similar overarching perspective, suggesting that nurses’ turnover decisions are based on reasoned action, that is, based on “a hierarchical sequence leading from beliefs, through attitudes and social norms, to intention, and finally, to behavior” (p. 221).

Approaching the turnover issue from a more affective orientation, Cheng et al. 15 examined the dynamics from an emotional labor perspective and noted that faking unfelt emotion and the act of hiding genuine emotion indirectly influenced turnover intention through poorer quality of care and burnout. Extending this perspective, Leiter and Maslach 16 found that the cynicism dimension of burnout was the most significant predictor of turnover, and Laschinger et al. 17 observed that in the nursing context workload and workplace bullying was a substantive predictor of burnout and turnover.

A few researchers adopted an exchange perspective to study nurses' turnover. For instance, Brunetto et al. 18 used a social exchange lens to find that the following factors strongly influenced nurses’ engagement and turnover: perceived organizational support, affective commitment, leader-member exchange, well-being and teamwork. In a related approach, Jourdain and Chênevert 19 examined nurses’ burnout and intention to leave the profession from a demands and resources perspective (with demand comprising of workload, stress levels, work-family balance, and relationship with physicians and clients, while resources referred to nurses’ competence, autonomy, meaning derived from work, support from supervisors and colleagues, and recognition from physicians and clients). Results showed that emotional exhaustion and depersonalization dimensions of burnout were impacted by the demands of the profession, and motivation was affected by the resources available; emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were also associated with psychosomatic complaints regarding sleep, appetite and health, and professional commitment, which, in turn, indicated the intention to leave the profession.

A fourth approach to understanding nurses' turnover was to use a systems perspective. O'Brien-Pallas et al. 5 examined nurses’ turnover using an inputs, throughputs and output framework. The data suggested that role ambiguity, role conflict and job satisfaction were strongly associated with turnover rates, as were team support, professional effectiveness, and employer care. Irvine and Evans 20 used a multidisciplinary perspective to demonstrate that nurses’ job satisfaction and turnover can be explained by economic (pay, training, labor markets), psychologic (demographic and individual characteristics), and sociologic (the work environment and context) factors. 21

Cluster 3: Types of turnover

A third stream of research in this area has distinguished between leaving the organization (e.g., department, hospital) and leaving the nursing profession. For example, Gerber et al. 22 proposed that the satisfaction nurses derive from the nature of the work itself, the quality of care, and the time available to do one’s job well impact turnover decisions connected to the profession. In contrast, turnover from the hospital per se is influenced by the levels of group cohesion, job stress and autonomy. In a similar vein, Parry 11 found that affective professional commitment and organizational commitment predicted turnover from nursing, while job satisfaction, organizational commitment and intention to change profession predicted nurses’ turnover. Results from more recent studies back up these findings and highlight the role of personal factors such as working hours, burnouts, alternate job offers, marital status and work-family balance in affecting intentions to quit the profession, while the intentions to leave the organization were related to the leadership and the local contexts. Adopting a more temporal angle to turnover, Flinkman and Salanterä 23 found that inadequate orientation and mentoring programs result in early career nurses’ turnover from the organization and from the nursing profession.

In sum, while the research to date has examined different antecedents, multiple perspectives, and various forms of nurses’ turnover, there is a paucity of inquiries aimed at formulating a framework that highlights the factors, specifically psychological states, that immediately precede the intention to quit and reflect the cumulative impact of different antecedents. What is needed is a conceptualization that is integrative and can capture why and how the numerous antecedents lead to different types of turnover. Such a framework would offer a parsimonious sensemaking of the turnover problem and make it more manageable for constructing solutions. Being able to predict different types of turnover is critical since the implications and remedies vary significantly.

A meaning-based view of nurses’ turnover

One theoretical lens, meaning-based view (see Rosso et al. 24 for a review), located at the level of existential needs 25 can help us understand, analyze and predict two types of turnover, that from the profession and that from the organization. The meaning associated with one's work has been shown to influence a range of outcomes such as motivation, 26 absenteeism, 27 career development, 28 identifying with the organization, 29 job satisfaction, 27 empowerment, 30 engagement 31 and work behavior. 32 Prior research has also noted how a lack of meaning can result in alienation, 33 frustration, 33 powerlessness, 33 low self-esteem, 33 and disengagement. 33 Such a wide application of meaningfulness as an explanatory lens highlights both its relevance and versatility for understanding individual behavior at work, including turnover decisions. It is especially suitable for the nursing context given the connotation nursing carries as work that is purposeful, rewarding, and rich with meaning in that it is associated with a deeper purpose and with service to others.

The meaning associated with one's work can be divided into meaning ‘in' work and meaning ‘at' work. 34 While these two forms of meaning are not mutually exclusive, a deficit in one is qualitatively dissimilar from a deficit in the other and signifies a differential impact on the type of turnover. Before delving into the implications of such a deficit in these two forms of meaning their essence is addressed.

Meaning “in” work

Meaning in work is a psychological state derived “from the intrinsic qualities of the work itself, the goals, the values, and the beliefs that the work is thought to serve” and pertains to the role or “what am I doing?” and not from “where that work is done” (Pratt and Ashforth, 34 pp. 311–315). It is the subjective sense of the deeper purpose that is drawn intrinsically from the relationship with work.34,35 When the work significantly reflects and contributes to shaping one’s identity and lends clarity of direction for expending effort, the work comes to occupy a central place in one’s life. It not only serves as the foundation for one’s self-conceptualization, but it also becomes an extension of one’s values and priorities and highlights a thread connecting one’s work-life and non-work life. High meaning in work generates feelings of making a positive difference, fulfilment, authenticity, and connectedness through the perceived alignment of the person’s purpose, values, self-efficacy, and self-worth with the work.24,36,37

Not surprisingly, such a sense of identity and purpose has powerful implications for a nurse’s level of engagement, motivation, resilience and fulfillment at work. But under what conditions does such connectivity to one’s work emerge? Do all nurses have this sense of identity and purpose? Recent research on work orientations28,35,38 suggests that those with a callings-orientation (as opposed to a job or career orientation) are likely to experience such a connection. Those with a callings orientation (a strong sense of their work as their calling) tend not to separate “living a life” from “earning a livelihood” and understand themselves in terms of what they do. In other words, the work they do carries such meaning that it shapes their narrative about their identities and purpose in life. If nurses were to consider what they do as a calling and experience high meaning in work, then it has direct implications for turnover. Not only are they likely to assess themselves and their success in subjective terms, but they will also react very differently to the dynamics and developments in the workplace. For example, prior research has noted that a callings-orientation may foster the acquisition of meta-competencies (e.g., adaptability) 39 and prompt viewing the work-related stressors as positive challenges and redirect attention from the possibility of failure to the joy of doing the task itself. The net impact, then, would be a shoring up of the nurses’ resilience that would lower the likelihood of turnover. If, on the other hand, nurses do not have a callings-orientation (merely saw the work as a job) and experienced low meaning in work, then the cumulative impact of inevitable setbacks, impediments, conflicts, extra demands in organizational settings combined with simple daily frustrations is likely to negatively impact the nurses and cause them to consider other kinds of work.

Meaning “at” work

Meaning at work is a psychological state derived from “the organizational community within which the work is embedded” and pertains to membership or “where do I belong?” and not from “what one does” (Pratt and Ashforth, 34 pp. 311–315). It signifies the sense of deeper purpose that is drawn extrinsically from the relationship with the work environment.36,37 Meaning at work is also a reflection of whether the work environment generates feelings of making a difference, fulfilment, authenticity, and connectedness.36,37 Work is usually situated in an organization wherein relationships with supervisor, co-workers, and other stakeholders are cultivated. These relationships are bound by the structure, the culture, and the reputation of the organization. 36 Being able to be authentic in these relationships and feel connected to supervisor, co-workers, and other members, the structure, the culture, and the reputation of the organization helps us to sense a positive meaning at work.24,40 These interpersonal relationships play an important role in making work and workplaces significant.41,42 Also relevant in this regard are factors such as the physical work environment, the resource support that is available, and the organizational practices and policies that enable or hinder work. The source of meaning at work is predominantly external to the self, and it is co-created along with others.

So, it remains to reason that when nurses experience high meaning at work that it signals a strong attachment to their workplace and a lower likelihood of leaving that organization. On the other hand, low meaning at work signals the absence or reduced presence of enriched relationships with one’s peers, inadequate support from one’s supervisor, poor working conditions, and organizational norms and routines that are not empowering. The net impact is a reduced presence or complete absence of a collection of factors that enable the nurse to perform to the best of his/her ability. Not surprisingly, nurses caught in such a work environment depleted of such organizational enablers are likely to quit the organization in search for a better work environment. It is important to note that the attribution for their sense of dissatisfaction and low engagement is to the work environment rather than the work per se. And, prior research on turnover has consistently highlighted a link between organizational enablers and turnover. 43

Meaning in work, meaning at work, and nurses' turnover

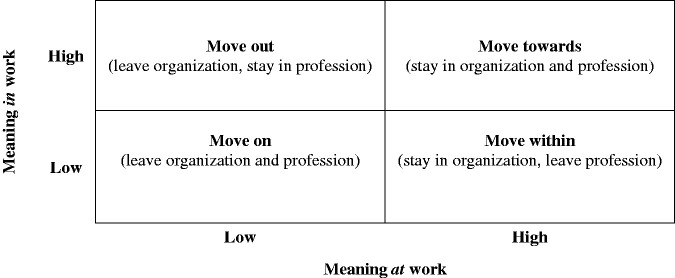

Combining these two dimensions – meaning in work and meaning at work - offers four distinct situations that nurses may find themselves in that results in three different kinds of turnover (please see Figure 1). Each situation carries with it qualitatively different implications for turnover and the three types of turnover call for different kinds of remedies. Figure 1 highlights four distinct situations. In the section below, each situation is explored in depth by presenting a scenario, highlighting the dynamics, and drawing out the implications for turnover.

Figure 1.

A meaning-based view of nurses’ turnover.

Move Within: Low meaning in work, high meaning at work (LMI/HMA)

Jason works as a camp nurse/medic in a remote mining area. His days consist of sitting in the truck and/or mobile office waiting for workers who may approach him usually for routine medical assistance. He does not think the work itself that stimulating; however, he enjoys the place where he works at and the people he works with. He gets paid well (more than he would be paid working in a hospital setting) and has use of a company vehicle and a laptop computer. He likes his rotation of three weeks on, two weeks off as it allows him some steady quality time at home with his kids. The company pays his travel time and expenses to and from work.

This cell describes a situation where a nurse experiences high meaning at work but doesn’t necessarily view nursing per se as meaningful. The high meaning at work may stem for a range of factors associated with the work environment - good pay and benefits, professional colleagues, personal friendships, supportive supervisor, positive work culture, sufficient resources, etc. As a result, this nurse may consider the work setting a good place to work and willingly embrace that organizational identity. But the low meaning he finds in the work itself would prompt him to search for alternate roles in his place of work. The turnover here is specific to quitting the work but not the organization. While this type of turnover has implications for operational costs and disruptions, it also has a silver lining. In this scenario, he may voluntarily remove himself from a role he doesn’t find meaning in to a role that is closer to his interests. Both the nurse and the organization gain - he is happier (and likely more productive) in his new role and the organization gets to retain a seasoned employee even if it is in a different part of the organization. Such a shift is also consistent with the notions of person-job fit 44 and job-crafting. 45

Move Out: High meaning in work, low meaning at work (HMI, LMA)

Marcia is a nurse who has significant operating room and rural health experience. She is passionate about nursing and 15 years ago took interest in complementary and alternative practices such as therapeutic touch. She has completed numerous courses in therapeutic touch and incorporates this technique into her daily nursing practice. Frustrated with a work environment and health system that is not fully supportive of complementary and alternative practices, she finds herself feeling increasingly isolated and hindered at work. She loves being a nurse but the lack of genuine acceptance towards her integrated practice is taking its toll on her well-being, and she dreads going to the hospital she works at.

This cell describes the situation where a nurse is passionate about and inherently engaged in her work but at the same time feeling frustrated and unhappy with the work environment. The low meaning at work stems from a lack of organizational enablers such as having a supportive supervisor, professional and helpful colleagues, and sufficient resources. But the meaning she finds in her work per se drives her to continue to perform regardless of the obstacles and frustrations she faces. This nurse runs the risk of burning out as she stretches her time and energy to a breaking point. In this situation, it is critical for hospital administration and her supervisor to recognize that engaging in the practice of nursing is much more important to this nurse than the place she practices at - she is likely to move to any other hospital that offers a more supportive environment. Her primary loyalty is to the nursing profession, not the organization where she is employed. This type of turnover does not bode well for the organization as it implies the loss of a truly dedicated nurse due to the inability or unwillingness of the organization to create a work environment where she can flourish. Severe and damaging as this type of turnover may be, it is also the relatively easiest one to fix since the onus rests entirely on the senior leadership of the organization. The turnover can be stemmed by addressing the conditions that cause such nurses to burn out – training supervisors to be more supportive and be a coach to these nurses, building a collaborative and high-trust culture, allowing the nurses room for job crafting to support their interests.

Move On: Low meaning in work, low meaning at work (LMI/LMA)

Ryan works as a staff nurse on a busy surgical floor of a large urban tertiary hospital. He has been working there for three years now and has a permanent full-time (1.0 FTE) position. His attitude towards work is that he ‘works to live’– his real passion is being a ski instructor. Plus, he is frustrated and disenchanted with the healthcare system because he thinks that the daily fast turnaround of patients gives him no time to get to know any of them and provide them with the quality care they deserve – the healthcare system feels like a drive-through service. He never gets to spend time with his supervisor since she is too busy managing three different units at once and with many of his colleagues being temporary employees, the whole unit has a transient feel to it. He considers his work as a temporary phase in his life as he dreams of being a ski instructor.

This cell describes a situation where a nurse finds neither the work itself nor the workplace/organization to be meaningful. In the absence of meaning in and meaning at work, there is not much that holds him back from quitting both the organization and the profession altogether. While the availability of other employment opportunities (different jobs, different organizations) and personal-life factors (e.g., family situation, kids in school, spousal employment) may prevent him from quitting right away, it is important to recognize the intention to quit is high. The implications are significantly negative for the organization and the nurse in this situation – he will drift along doing the minimum necessary so as not to lose his job. There is a sense of feeling lost and being held captive in his job and wanting to leave with the first acceptable employment opportunity that comes along. The lack of enthusiasm and motivation coupled with a pervasive negativity towards his work and the organization means low productivity, minimal citizenship behavior, and poor engagement. In this situation, it is better such nurses quit and management should encourage them to leave since their staying in their current role does more harm than good.

Move Towards: High meaning in work, high meaning at work (HMI, HMA)

Denise is a registered nurse and site manager of a small rural hospital. She worked as a staff nurse for several years prior to taking on the administrative role five years ago. Denise has a reputation of being a wonderful and caring nurse, very knowledgeable and competent, and relates well and empathically with clients and fellow staff. With Denise, it always seems that no matter what is going on in the work environment, her practice of nursing is never rushed or jeopardized due to context or factors beyond her control. She has a strong network of support around her and many of her fellow staff members are close friends and socialize together outside of work on a regular basis. Denise has the respect and support of management and if ever she indicates a need or problem in the work environment, management does all they can to accommodate.

This cell describes a situation where a nurse sees her work as inherently meaningful (high meaning in work) as well as deeply appreciates the place where she works (high meaning at work). This is an ideal state for both the nurse and the organization - she is driven, committed and deeply engaged in her work and embraces her identity as a nurse and as member of the hospital team. The hospital gains from the presence and performance of such dedicated nurses - it’s a win-win situation. These nurses “burn for” nursing and continue to move towards self-actualization as a nurse - there is likely to be low or no turnover in such a situation.

Discussion and implications

The meaning-based view of nurses’ turnover sheds light on aspects of meaning that nurses may attach to the work they do and their place of work and highlights the need for a contingency approach to addressing the problem. The dimensions of meaning in and meaning at work raise a few interesting questions about their nature and boundaries of their impact.

First, it is important to note that the meaning-based view focuses more on turnover intentions rather than turnover itself. Whether nurses leave their hospitals, or their profession may be a function of the availability of other job options, necessity of earning a livelihood, family and personal constraints in shifting jobs or locations, etc. In other words, an intention to quit need not automatically lead to quitting. But it underscores a different kind of a problem - the cost of having disengaged nurses who want to quit (either the organization, profession or both) but are not doing so right away due to some reason or the other. They merely go through the motions at work and wait for the right time and situation to quit. Organizations are then left to face the costs of this disengagement in the form of withdrawn role performances. 46

Second, the role of attribution in meaning in and meaning at work needs to be explored. For example, when people have a negative experience at work, are they attributing that to the work context (meaning at work) or are they attributing that to the work itself (the lack of meaning in work), and what are the implications of possible misattributions. If the root of the problem is a lack of meaning in work but is misattributed to a lack of meaning at work, this may result in nurses going on a fruitless chase moving from one healthcare organization to the other, not realizing that the best course of action (for them) would be to change occupations. In the absence of such a realization, the nurses go through a prolonged state of frustration about their work lives while the organizations expend resources and energy coping with a turnover problem that could have been avoided. Likewise, if the problem is a lack of meaning at work but is misattributed to a lack of meaning in work, this once again leads to a turnover that could have been prevented by addressing the organizational and workplace deficiencies (e.g., more supervisory support, coaching, positive work culture, more resources and workload management issues). Instead, the misattribution may prompt not only the nurses who are frustrated to mistakenly change professions (and cost the organization in terms of replacement time and resources) but the negative conditions that caused the frustration in the first place may continue to fester unchecked and uncorrected and lead to even more turnover. In this scenario, the organizations and society at large end up losing nurses who are truly committed to nursing and may have emerged as valuable practitioners in their respective specializations.

Third, the meaning in work and meaning at work dimensions may not be independent constructs but have a bi-directional relationship with each other. On the one hand, the two constructs are likely to be positively related to each other due to a spill-over effect - high (low) meaning in work may create a positive (negative) halo effect that could enhance (diminish) the meaning at work; alternatively, high (low) meaning at work may cast a positive (negative) light on meaning in work itself. While the extent to which such a spill-over effects exists and how robust it may be is a matter of empirical inquiry, a likely positive correlation between these two dimensions highlights the extra value gained even if an organization were to tackle just one of these dimensions. On the other hand, there might also be an interesting trade-off between these two dimensions. Pratt and Ashforth 34 noted that meaning in work “… may involve a disengagement from the organization, as it is the task itself – not where it is done – that is of ultimate importance” (p. 325). In other words, those who see a lot of meaning in their work may not pay as much attention to or be concerned about meaning at work; similarly, it is possible that some who perceive a high meaning at work are content enough to worry less about meaning in work. What this suggests is that the weighting attached to these dimensions may not necessarily be equal and that these two different facets of meaning may have varying importance to different nurses.

Finally, it is useful to note is that the existing literature mostly assumes that meaning in and at work are positive psychological states (see Rosso et al. 24 for a review). However, there is a thin line between states of low meaning in and at work and feelings of meaninglessness or negative meaning in and at work. The literature suggests that negative meaning in and at work leads to alienation, cynicism, frustration, powerlessness, dissatisfaction, disengagement, low self-esteem, doubting the worth of the work, and the intention to quit.33,47–52 If so, senior leaders and supervisors in hospitals need to be vigilant for any signs that their nurses may be seeing negative meaning in and at work and be proactive in stemming such negativity. In fact, they would need to go beyond eliminating such negativity and create the conditions for positive meaning.

Conclusion

In this paper, turnover among nurses is explored through the dimensions of meaning in and meaning at work. A meaning-based view of nurses’ turnover is proposed that adds both depth and nuance to the understanding of this phenomenon and holds promise in terms of offering tailored remedies. But even as the dimensions collectively shed light on aspects of meaning that nurses may attach to the work they do, they also raise interesting questions about their nature and boundaries of their impact. While empirical research is needed to assess the proposed model, the implications for practice is that if the type of meaning that is lacking is understood, it will be easier to find the appropriate remedy.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declare(s) that there is no conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Anirban Kar https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9445-0405

References

- 1.Falatah R, Salem OA. Nurse turnover in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: an integrative review. J Nurs Manag 2018; 26: 630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS. Growing nursing numbers. Literature review of nurses leaving the NHS. Developing people for health and healthcare, [/www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Nurses%20leaving%20practice%20-%20Literature%20Review.pdf; 1-28 (accessed 1 April 2021).

- 3.. KPMG. K. U.S. hospital nursing labor costs study [internet]. 2011. Available from: http://www.natho.org/pdfs/KPMG_2011_Nursing_LaborCostStudy.pdf; 1-16. (2011, accessed 1 April 2021)

- 4.Duffield CM, Roche MA, Homer C, et al. A comparative review of nurse turnover rates and costs across countries. J Adv Nurs 2014; 70: 2703–2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Brien-Pallas L, Murphy GT, Shamian J, et al. Impact and determinants of nurse turnover: a pan‐Canadian study. J Nurs Manag 2010; 18: 1073–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rondeau KV, Wagar TH. Human resource management practices and nursing turnover. J Nurs Educ Pract 2016; 6: 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H-C, Chu C-I, Wang Y-H, et al. Turnover factors revisited: a longitudinal study of Taiwan-based staff nurses. Int J Nurs Stud 2008; 45: 277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parasuraman S. Nursing turnover: an integrated model. Res Nurs Health 1989; 12: 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nei D, Snyder LA, Litwiller BJ. Promoting retention of nurses: a meta-analytic examination of causes of nurse turnover. Health Care Manage Rev 2015; 40: 237–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vardaman JM, Cornell PT, Allen DG, et al. Part of the job: the role of physical work conditions in the nurse turnover process. Health Care Manage Rev 2014; 39: 164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parry J. Intention to leave the profession: antecedents and role in nurse turnover. J Adv Nurs 2008; 64: 157– 167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang J-I, Park H-A. Nurses’ perception of ethical climate, medical error experience and intent-to-leave. Nurs Ethics 2014; 21: 28–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takase M. A concept analysis of turnover intention: implications for nursing management. Collegian 2010; 17: 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prestholdt PH, Lane IM, Mathews RC. Nurse turnover as reasoned action: development of a process model. J Appl Psychol 1987; 72: 221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng C, Bartram T, Karimi L, et al. The role of team climate in the management of emotional labour: implications for nurse retention. J Adv Nurs 2013; 69: 2812–2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leiter MP, Maslach C. Nurse turnover: the mediating role of burnout. J Nurs Manag 2009; 17: 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laschinger HKS, Grau AL, Finegan J, et al. Predictors of new graduate nurses’ workplace well-being: testing the job demands–resources model. Health Care Manage Rev 2012; 37: 175–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunetto Y, Xerri M, Shriberg A, et al. The impact of workplace relationships on engagement, well‐being, commitment and turnover for nurses in Australia and the USA. J Adv Nurs 2013; 69: 2786–2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jourdain G, Chênevert D. Job demands – resources, burnout and intention to leave the nursing profession: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2010; 47: 709–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irvine DM, Evans MG. Job satisfaction and turnover among nurses: integrating research findings across studies. Nurs Res 1995; 44: 246–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coomber B, Barriball KL. Impact of job satisfaction components on intent to leave and turnover for hospital-based nurses: a review of the research literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2007; 44: 297–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerber RM, Hinshaw AS, Atwood J. Anticipated turnover among nursing staff. Arizona Nurse 1983; 36: 5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flinkman M, Salanterä S. Early career experiences and perceptions – a qualitative exploration of the turnover of young registered nurses and intention to leave the nursing profession in Finland. J Nurs Manag 2015; 23: 1050–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosso BD, Dekas KH, Wrzesniewski A. On the meaning of work: a theoretical integration and review. Res Organizational Behav 2010; 30: 91–127. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frankl VE. Man's search for meaning. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Motivation through the design of work: test of a theory. Organizational Behav Hum Performance 1976; 16: 250–279. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wrzesniewski A, McCauley C, Rozin P, et al. Jobs, careers, and callings: people's relations to their work. J Res Pers 1997; 31: 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dik BJ, Duffy RD. Calling and vocation at work: definitions and prospects for research and practice. Counsel Psychol 2009; 37: 424–450. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pratt MG, Rockmann KW, Kaufmann JB. Constructing professional identity: the role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. AMJ 2006; 49: 235–262. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spreitzer GM. Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Acad Manag J 1996; 39: 483–504. [Google Scholar]

- 31.May DR, Gilson RL, Harter LM. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J Occup Organizational Psychol 2004; 77: 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berg JM, Wrzesniewski A, Dutton JE. Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: when proactivity requires adaptivity. J Organiz Behav 2010; 31: 158–186. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steenkamp PL, Basson JS. A meaningful workplace: framework, space and context. HTS Theological Stud 2013; 69: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pratt MG. and Ashforth Be Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. In: Cameron KS, Dutton JE and, Quinn RE. (eds) Positive organizational scholarship: foundations of a new discipline. Chapter 20. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 2003, pp. 309–327. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wrzesniewski A. Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. In: Cameron KS, Dutton JE, Quinn RE. (eds) Positive organizational scholarship: foundations of a new discipline. Chapter 19. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 2003, pp. 296–308. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chalofsky NE. Meaningful workplaces: Reframing how and where we work. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. The pursuit of meaningfulness in life. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ. (eds) Handbook of positive psychology. Chapter 44. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, pp.608–618. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elangovan A, Pinder CC, McLean M. Callings and organizational behavior. J Vocational Behav 2010; 76: 428–440. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall DT, Chandler DE. Psychological success: when the career is a calling. J Organiz Behav 2005; 26: 155–176. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wrzesniewski A, Dutton JE, Debebe G. Interpersonal sensemaking and the meaning of work. Res Organizational Behav 2003; 25: 93–135. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant AM. Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. AMR 2007; 32: 393–417. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barry B, Crant JM. Dyadic communication relationships in organizations: an attribution/expectancy approach. Organization Sci 2000; 11: 648–664. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carter MR, Tourangeau AE. Staying in nursing: what factors determine whether nurses intend to remain employed? J Adv Nurs 2012; 68: 1589–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kristof ‐Brown AL, Zimmerman RD, Johnson EC. Consequences of individuals' fit at work: a meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychol 2005; 58: 281–342. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wrzesniewski A, Dutton JE. Crafting a job: revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. AMR 2001; 26: 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kahn WA. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad Manag J 1990; 33: 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scroggins WA. Antecedents and outcomes of experienced meaningful work: a person-job fit perspective. J Business Inquiry 2008; 7: 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cartwright S, Holmes N. The meaning of work: the challenge of regaining employee engagement and reducing cynicism. Hum Resour Manag Rev 2006; 16: 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holbeche L, Springett N. In search of meaning in the workplace. UK: Roffey Park Institute Limited, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chalofsky N. An emerging construct for meaningful work. Hum Resour Dev Int 2003; 6: 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ashforth BE, Mael F. Social identity theory and the organization. AMR 1989; 14: 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cummings TG, Manring SL. The relationship between worker alienation and work-related behavior. J Vocational Behav 1977; 10: 167–179. [Google Scholar]