Abstract

Introduction:

Hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation may contribute to symptom burden in bipolar disorder (BD). Further characterization of cortisol secretion is needed to improve understanding of the connection between mood, sleep, and the HPA axis. Here, we observe diurnal cortisol patterns in individuals with BD and healthy controls (HC), to determine time points where differences may occur.

Methods:

Salivary cortisol was measured at six time points (wake, 15, 30, 45 minutes after wake, between 2–4 PM, and 10 PM) for three consecutive days in individuals with symptomatic BD (N=27) and HC participants (N=31). A general linear model with correlated errors was utilized to determine if salivary cortisol changed differently throughout the day. between the two study groups.

Results:

A significant interaction (F = 2.74, df = 5, p = 0.02) was observed between the time of day and the study group (BD vs. HC) when modeling salivary cortisol over time, indicating that salivary cortisol levels throughout the day significantly differed between the study groups. Specifically, salivary cortisol in BD was elevated compared to HCs at the 10PM timepoint (p = 0.01).

Conclusion:

Significantly higher levels of cortisol in participants with BD in the nighttime suggest the attenuation of cortisol observed in healthy individuals may be impaired in those with BD. Re-regulation of cortisol levels may be a target of further study and treatment intervention for individuals with BD.

Keywords: Bipolar Disorder, Cortisol, Mood Disorders, Stress

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a recurrent, episodic mood disorder marked by periods of depression and mania which affects roughly 1% - 4% of the world’s population, with an average age of onset in young adulthood [1, 2]. Individuals with BD present with episodes of mania or hypomania characterized by elevated mood, energy, and impulsivity and/or episodes of depression characterized by depressed mood, cognitive difficulties, and lethargy [3]. BD is difficult to diagnose, given overlapping symptoms with other disorders, including depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Even within well-diagnosed BD there is significant heterogeneity of phenotypes. BD has a strong genetic underpinning [4], and mood disruption in BD has been linked to neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress [5], circadian dysregulation [6], and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) stress response axis [7]. Further characterization of the biological underpinnings of BD phenotypes is imperative in developing effective treatments.

Biological responses to stress, whether psychological or physical, invoke a complex system that can improve performance on meaningful tasks or interactions [8]. However, abnormal activation or suppression of the stress system can lead to behavioral, psychological, and physiological responses that impair performance and health [9, 10, 8, 11]. The HPA axis is the key stress response-modulating system in vertebrates. In this signaling pathway, the hypothalamus secretes corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), in turn stimulating release of adrenal corticotropic hormone (ACTH) by the pituitary gland [10, 8]. ACTH then stimulates the release of cortisol from the adrenal cortex into the bloodstream [12]. Cortisol itself interacts with many organ systems throughout the body to mediate the stress response [12]. Cortisol release follows a diurnal pattern in healthy individuals; it peaks shortly after waking [13, 14] and reaches its nadir during the night [15].

Although HPA axis dysregulation has been shown to be present in BD and other mood disorders, it is unknown what role the circadian cycle plays in that dysregulation, and if dysregulation is the same in depression, mixed states and mania. Overall, increased HPA axis activity has been noted in BD participants, particularly those in hypomanic and/or depressive episodes [16, 17]. Others found an increased cortisol level at bedtime in BD individuals with a history of suicide attempts compared to BD individuals without a suicide attempt [18]. Interestingly, there were no observable differences in cortisol levels throughout the day when investigating BD participants in remission [19]. These findings led to the investigation of HPA axis-targeting drugs as therapeutics for BD [20]; which have shown some promise [21, 22].

Incidentally, aside from associations with BD, HPA axis activity also strongly associates with sleep patterns and quality, which are themselves commonly disrupted in BD [23]. For instance, intravenous administration of CRH in adult males decreases the amount of time the participants spent in REM and slow wave sleep [24]; this effect may be compounded by age [25]. High salivary cortisol in the morning has been associated with self-report of chronic insomnia symptoms [23], and individuals with a shorter sleep duration (less than six hours a night) showed a decreased cortisol response in the morning but a flatter diurnal cortisol pattern through the rest of the day [26]. Sleep disturbance is a hallmark of both depressive and manic episodes and demonstrated through both subjective and objective measures [27–29]. HPA axis dysregulation may help explain the sleep disturbances observed in BD. Studies have shown mixed observational trends on patterns of cortisol levels, likely due to timing of observation (e.g.: only looking at the morning). Additional confounds include heterogeneity of participant mood state and context or setting (home, lab, hospital) of assessments. Here, we evaluate diurnal cortisol patterns throughout the day in BD participants during an active mood state in an inpatient psychiatric hospital. We hypothesized that BD participants would have a significantly different diurnal cortisol pattern when compared to healthy controls (HC) at key anchored time points throughout the day. Given prior research presenting the important relationship between stress levels and sleep quality, we conducted an exploratory secondary analysis on the association between nighttime cortisol and subjective and objective sleep measures for that night.

Materials and Methods

Recruitment

Thirty subjects with BD diagnosed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV, [3]) criteria were recruited during a hospital stay to participate in a study of polyunsaturated fatty acid, inflammatory, and HPA axis biomarkers during mood episodes, see Saunders [30]; three participants were excluded from this analysis due to not collecting saliva with a final sample of 27 participants (24 with BD I, 3 with BD II). Thirty-one HC participants were recruited in central Pennsylvania through flyers and screened on the phone. Participants were screened for inclusion criteria (a primary diagnosis of current BD I or II for the BD group and no personal history of psychiatric diagnosis or treatment for the HC group) and exclusion criteria, including pregnancy, substantial intellectual impairment (IQ < 70), comorbid major endocrinological or rheumatological illnesses, unable to give informed consent, or the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) daily. During an in-person appointment (baseline visit), each participant received a verbal description of the study, was given the opportunity to read the consent form, and all questions were answered. Individuals who agreed to the study signed the consent form. The study was approved by the Penn State University College of Medicine institutional review board (IRB Protocol: 39364EP).

Clinical Assessments

At baseline, all participants were interviewed using the Mini Neuropsychiatric Interview, a DSM-IV TR-based structured interview. Current mood state was assessed with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-21 plus Atypical (HDRS, [31]), the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS, [32]), and the Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania (CARS-M)[33]. Mood state was defined by the following criteria: HDRS-21 + AT scores between 0 and 6 indicated no depression, scores between 7 and 17 indicated mild depression, scores between 18 and 24 indicated moderate depression, and scores over 24 indicated severe depression. YMRS scores below 7 were considered not manic, scores between 7 and 12 were mild, and scores above 12 were severe manic phenotypes. A combination of clinically significant manic and depressed symptoms defined a mixed-manic phenotype (MM). Composite scores for the HDRS and YMRS were set to missing if any component question(s) were missing. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using height and weight measurements [34]).

Sample Collection

Saliva was collected for three consecutive days, six times per day. BD participants had samples collected in the hospital and stored by clinical staff. HC participants collected samples at home and returned them to the study team. The collection times were similar to Deshauer et al. [19], which included: upon waking, 15 minutes after waking, 30 minutes after waking, 45 minutes after waking, between 2:00 and 4:00 pm, and at 10:00 pm. Both groups were provided salivettes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht) to collect saliva samples and were advised not to eat or drink (except water), brush their teeth, or smoke 30 minutes before collection. Samples were refrigerated until all the daily samples were collected and returned to the study team.

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Each saliva sample was analyzed for cortisol concentrations using an ELISA kit. This analysis was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions (ALPCO #11-CORHU-E01-SLV). Each sample was measured in triplicate for each time point, for which an average cortisol value was calculated at each time point per day.

Subjective Measurement of Sleep

Subjective sleep quality was measured with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [35]. The PSQI is a well-validated, self-rated scale with nineteen individual items, which generate seven component scores and a total score referencing sleep quality in the past month. Composite scores were missing if any component data was missing. Sleep latency in minutes and total sleep time in hours were reported as collected on the PSQI, while the ratio of the amount of time asleep versus the amount of time in bed was used to calculate total sleep efficiency as a percentage [36]. In our sample, it was possible for participants to respond to the survey items in such a way that allowed their total time asleep to exceed their total time in bed. For these instances, the sleep efficiency is capped at 100% [36, 37].

Objective Measurement of Total Sleep Time (TST)

During the period of initial evaluation, participants wore an actigraph (Sleepwatch-O, Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc., Ardsley NY) as described previously [29], a watch-like device that measures acceleration, on the non-dominant hand for 7 days. Participants maintained a sleep log, which combined with the actigraphy recording, provides accurate measure of objective sleep measures. Actigraphy sleep variables were calculated with ActiLife V.6.4.5 software (Actigraph Corporation, Pensacola, FL), including total sleep time (TST), wake after sleep onset, sleep latency, sleep duration, and sleep efficiency. BD participants completed the actigraph protocol during hospitalization and healthy controls completed the recording at home. See Krishnamurthy, et al (2018) for report of the primary sleep findings. Dates of actigraphy recordings were matched with cortisol collection dates where possible, in order to explore the relationship between salivary cortisol and that night’s sleep measures. On occasions where actigraphy data collection was unable to be date-linked with the participant’s saliva sample collection date, the actigraph sleep data was left unmatched (unassigned), and was treated as missing data for analysis purposes.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline demographic characteristics stratified by study group are summarized and compared. The Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used for continuous measures, and the exact Pearson Chi-Square test was used for categorical measures. A general linear model with correlated errors was used to account for repeated measures of cortisol throughout the six time-points of the days. The day-effect was removed by taking the time-point mean across days, resulting in one value for each time point. These values were averaged over a maximum of 3-days, therefore the cortisol value for each time point represents the mean value for the number of days available for that time-point (e.g. if 2 days of cortisol data are available for the wake sample, then the analytical wake cortisol value is representative of a 2-day mean). Due to the nature of this study, it was not expected that day-to-day cortisol measures within each individual would vary on a large scale, and the 3 days of salivette sample collection were not always consecutive. Therefore, the daily measures acted as resampling replicates within each participant to obtain mean values to prevent missing data samples (e.g. as long as the participant provided at least one saliva sample for any of the times throughout the day for any of the three days, their data could then be used in the analysis without exclusion). The model included fixed effects for the diagnosis (BD vs. HC), the time of day (Wake, + 15 min, + 30 min, + 45 min, 2–4PM, 10PM), and the two-way interaction between the diagnosis and the time of day. For this analysis, time of day was treated as a categorical measure. The outcome, the 3-day mean salivary cortisol, was natural-log transformed to strengthen the normality assumption of the model. The results are reported after back-transforming to the original scale via exponentiation of the model’s Least Squares Mean estimates (Geometric Means) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. SAS 9.4 was used to generate all statistical summaries and to perform all statistical analyses at a significance level of α = 0.05.

Based on the separation observed at the 10PM time point between the diagnosis groups, additional post-hoc exploratory analyses evaluating the role of 10PM salivary cortisol levels on that night’s sleep were explored. Sleep measures of interest included both objective (3-day actigraphy) and subjective (baseline PSQI – reflective of past 30 days) measures, for outcomes such as total sleep time, sleep efficiency, WASO (objective measure only), sleep latency and total PSQI score (subjective measure only). Descriptive data for these outcome measures are further summarized for the study sample in Table III. Simple linear regression models were fit, modeling each sleep measure as an outcome (reflective of a 3-day mean for actigraphy measures). The effects of the diagnosis group, 3-day mean 10PM salivary cortisol, and the two-way interaction between them were assessed (data not shown).

Table III.

Sleep Measures in Participants with BD and Healthy Controls. . Sleep measures are summarized for participants with BD and HCs. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) measures characterize subjective sleep and actigraphy measures characterize objective sleep.

| Bipolar (n=27) | Control (n=31) | |

|---|---|---|

| PSQI Total Sleep Time (Hours – Q4 of the PSQI) Mean (SD) | 6.30 (2.43) | 7.43 (0.97) |

| PSQI Sleep Efficiency (tmphse) a Mean (SD) | 80.94 (18.50) | 91.91 (9.09) |

| PSQI Sleep Latency (Minutes – Q2 of the PSQI) Mean (SD) | 63.52 (55.98) | 14.23 (11.36) |

| PSQI Total Score Mean (SD) b | 10.50 (4.55) | 2.67 (1.57) |

| Actigraph Night After Sleep Efficiency Mean (SD) c | 85.93 (12.64) | 85.38 (8.53) |

| Actigraph Night After Wake After Sleep Onset (number of wakings) Mean (SD) c | 57.54 (48.67) | 58.71 (39.88) |

| Actigraph Night After Total Sleep Time (minutes) Mean (SD) c | 415.65 (102.32) | 418.92 (70.30) |

Values exceeding a sleep efficiency of 100% were top-coded at 100%

n = 1 missing value in Bipolar group; n = 4 missing values in Control group

n = 6 missing value in Bipolar group; n = 1 missing values in Control group

Note that the reported actigraphy data refers to the night after the cortisol sample was taken. The values reported for each participant represent a 3-day mean of non-missing data (e.g. if only 2-days of actigraphy data were available and/or matched the corresponding dated cortisol samples, then the mean represents a 2-day average, etc.).

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

Demographics and clinical features of the analytic sample are presented in Table I. In our analytical sample, BMI (30.5 vs. 24.9) and smoking rate (60% vs. 3%) were significantly higher in the BD group compared to the HC group (p < 0.001; Table I). Marital status and employment also shared a significant association with the study group, as the majority of those with BD never married and/or were unemployed, compared to the majority of HCs being married and/or employed. Age, sex, race, and ethnicity were not significantly different between the study groups in our sample population (Table I). Of the BD participants, one was in a manic episode, ten were in a depressive episode, and sixteen were in a mixed-manic episode. No data was collected for lifetime counts for mood states within these participants.

Table I.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics Data. Listed are demographics and clinical characteristics summarized by study group. Continuous measures are summarized by Mean (Standard Deviation). Categorical measures are summarized by Frequency (Column Percentage).

| Bipolar (n=27) | Control (n=31) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) Mean (SD) | 35.33 (10.70) | 32.19 (11.28) | 0.13 |

|

| |||

| BMI (kg/m2) Mean (SD) | 30.52 (5.57) | 24.86 (4.72) | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| CARS-M Mean (SD) a | 16.69 (13.40) | 0.00 (0.00) | -N/A |

|

| |||

| HDRS-21 + Atypical Mean (SD) b | 35.00 (15.09) | 0.29 (0.59) | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| YMRS | 13.00 (11.13) | 0.00 (0.00) | N/A |

|

| |||

| Sex n (%) | 0.60 | ||

| Female | 13 (48.15) | 18 (58.06) | |

| Male | 14 (51.85) | 13 (41.94) | |

|

| |||

| Race n (%) b | 0.13 | ||

| Asian | 0 (0.00) | 4 (12.90) | |

| African-American | 1 (3.85) | 1 (3.23) | |

| White | 24 (92.31) | 26 (83.87) | |

| More than One Race | 1 (3.85) | 0 (0.00) | |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity n (%) | 1.00 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (3.70) | 2 (6.45) | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 26 (96.30) | 29 (93.55) | |

|

| |||

| Marital Status n (%) | 0.03 | ||

| Married | 6 (22.22) | 16 (51.61) | |

| Separated | 1 (3.70) | 1 (3.23) | |

| Divorced | 3 (11.11) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Never Married | 17 (62.96) | 14 (45.16) | |

|

| |||

| Smoking Status n (%) c | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 10 (40.00) | 30 (96.77) | |

| Yes | 15 (60.00) | 1 (3.23) | |

|

| |||

| Employment n (%) c d | < 0.001 | ||

| Unemployed | 13 (52.00) | 2 (6.45) | |

| Disability | 5 (20.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Employed | 6 (24.00) | 17 (54.84) | |

| Student | 1 (4.00) | 11 (35.48) | |

| Retired | 0 (0.00) | 1 (3.23) | |

n = 1 missing value in Bipolar group; n = 2 missing values in Control group

n = 1 missing value in Bipolar group

n = 2 missing values in Bipolar group

Employment status was captured as a free-text field asking participants for their occupation. Disability includes any response mention of ‘disabled’, ‘disability’, or ‘SSDI’. Those coded as ‘Employed’ considered all job titles provided, including those identifying as ‘housewife’ or ‘homemaker’. Student includes any response mention of ‘student’, such as ‘doctoral student’, ‘graduate student’, ‘medical student’, ‘nursing student’, etc. Missing, unknown, or not reported values for presented measures are not included in the denominators of percentages or statistical tests of association.

Participant use of medications for treatment during the study was also recorded. 23 of the BD participants were taking mood stabilizing medications, 17 BD participants were taking antipsychotics, 12 were taking antidepressants, 17 BD participants were taking sedatives, and 4 BD participants were taking other medications. No participants were taking stimulant medication. The HC participants, in contrast, were not taking drugs from any of the listed classes above, except for one HC taking a medication from the “other” category.

Diurnal Salivary Cortisol

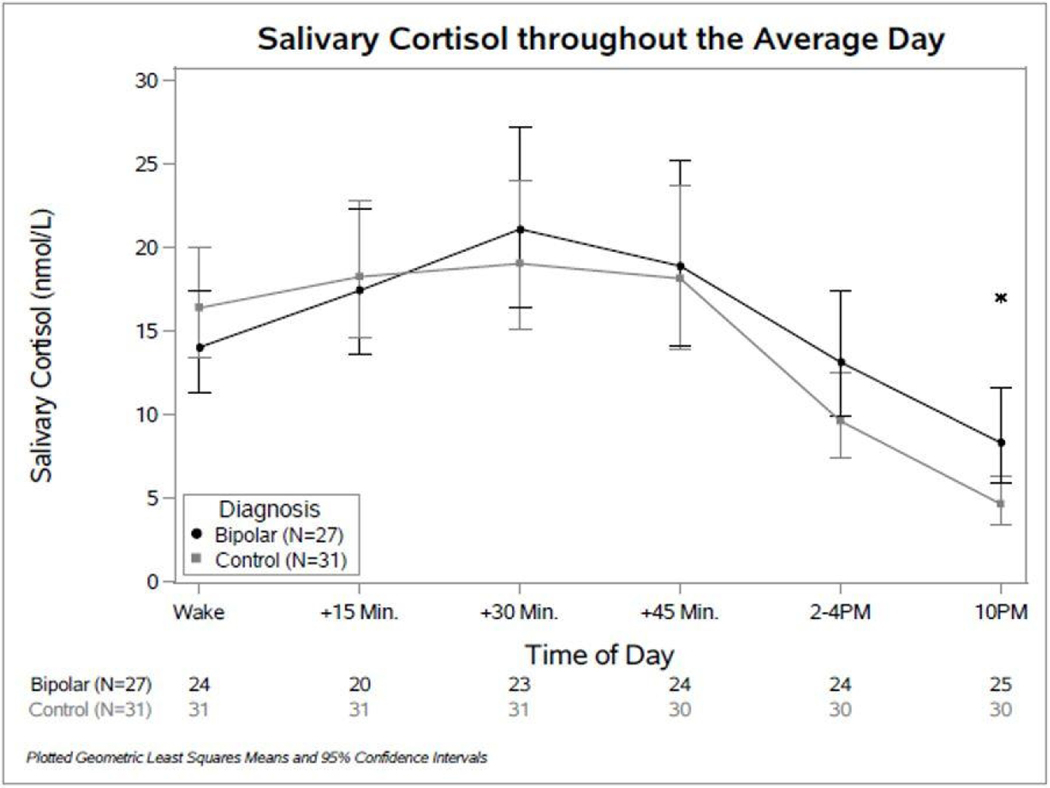

A significant interaction (p = 0.02) was observed between the time of day and the study group (BD vs. HC) when modeling salivary cortisol over time throughout the average day. Figure 1 plots the geometric mean estimates and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals for each diagnosis group over time throughout the average day. Comparisons between conditions at each time point showed that cortisol levels in those with BD were significantly higher at 10PM than those for the HCs (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Diurnal Cortisol Patterns in Bipolar and Healthy Control Participants. Comparison of Salivary Cortisol throughout the Day: Points plotted show geometric means with 95% confidence intervals at each time point. Sample sizes at each time point are listed below the graph.

Table II.

Ratio of Geometric Mean Comparisons Between BD and HC Participants in Salivary Cortisol Throughout the Day. This table reports the ratio of geometric mean estimates (and 95% confidence intervals) comparing salivary cortisol in BD and HC participants throughout the average day.

| Time | Ratio of Geometric Means (BD/HC) | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wake | 0.86 | (0.64, 1.15) | 0.30 |

| + 15 Minutes | 0.96 | (0.69, 1.33) | 0.78 |

| + 30 Minutes | 1.11 | (0.79, 1.56) | 0.55 |

| + 45 Minutes | 1.04 | (0.70, 1.54) | 0.84 |

| 2–4 PM | 1.37 | (0.93, 2.01) | 0.11 |

| 10 PM | 1.79 | (1.13, 2.84) | 0.01 |

Sleep Quality

No significant two-way interactions were observed for any of the sleep outcomes, resulting in the removal of these higher-level terms from the model and refitting main effects only. When modeling actigraphy sleep measures (BD n = 20; HC n = 29), no main effects were statistically significant. The 3-day mean 10PM salivary cortisol did not have a significant effect on that night’s sleep efficiency (p = 0.60), total sleep time (p = 0.85), or wake after sleep onset (WASO; p = 0.76). However, when modeling the PSQI sleep measures (BD n = 25; HC n = 30), the diagnosis group was consistently significant for all outcomes explored. The association between PSQI-measured poor sleep and BD was reported for this study (29). Those with BD reported a higher overall PSQI total score (poorer sleep quality; BD n = 24, HC n = 26; p < 0.01), less total sleep time in hours (p = 0.03), less sleep efficiency (p < 0.01), and more sleep latency (p < 0.01), on average, while adjusting for 3-day mean 10PM salivary cortisol (which was not a significant factor in any of the models; p = 0.94, p = 0.75, p = 0.67, p = 0.85, respectively). Only group differences were observed with respect to self-reported perceived sleep (subjective), but not in regards to objective sleep measurements. There was no evidence that 10PM salivary cortisol levels had any discernable effect on that night’s sleep.

Discussion

This study showed that individuals with BD have a significantly different diurnal pattern of cortisol than HC, with post-hoc comparisons demonstrating that participants with BD had higher cortisol than HC at the nighttime time point, which may have a number of implications. Diurnal variation of cortisol is a dynamic process, and the biologic effects of changes in the rhythm of the cortisol level is important for sleep, appetite, energy, cognition and immune functioning [38]. An elevated cortisol level at a time of day when the level should be lower due to diurnal variation is described as a flattening of the diurnal curve and can contribute to hyperarousal in these systems, as shown in insomnia [39]. Overall, this ‘flattened’ pattern is similar to the pattern observed in MDD patients, where cortisol levels do not properly decline as the day progresses (Jarcho et al., 2013). The significantly higher cortisol observed at the 10 PM timepoint could relate to findings on the association of mood states with circadian disruption and increased likelihood of being more active at night [40]. Several studies have found a positive correlation between the severity of depressive symptoms and circadian rhythm changes and subjective sleep disturbances [41, 42]. Although nighttime cortisol was not significantly associated with subjective sleep measures, the BD group had significantly worse subjective sleep perceptions than the healthy controls.

In contrast to previous reports of significantly elevated morning cortisol levels in patients in depressive or euthymic episodes [17], we saw no significant differences in the morning. This disparity may in part be due to variability in the time of sampling between studies in their meta-analysis. Blood cortisol levels were measured in a majority of the participants (~75%) for their meta-analysis as opposed to our salivary measures, but they reported no significant difference between the collection methods. Our results were similar to others who found higher nighttime cortisol in blood samples from males hospitalized with an episode of mania [43].

Strengths and Limitations

While the general trends observed in this study may share similarities with previously reported literature, it is worth mentioning that our study has limitations. Firstly, this was a cross-sectional study where causal relationships cannot be determined, and data were not collected on lifetime burden of bipolar disorder in this sample. Additionally, all BD participants were housed in an inpatient setting, while HCs were given instructions for at-home collection. Although this allowed for examination of acutely symptomatic patients with BD, the differences in environment and routine could be a confounder for the results. We observed patients during active episodes, thus potentially providing improved detection of differences in diurnal cortisol. Additionally, inpatient housing increased the reproducibility of the sample collection timing and ensured proper collection methodology. Finally, given our relatively small sample size, we were unable to recruit sufficient numbers of purely manic episode individuals to explore meaningful comparisons between mood states. Future research analyzing cortisol patterns between mood states may contribute further to our understanding of diurnal cortisol dysregulation in bipolar disorder.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study investigated the diurnal cortisol pattern throughout the day for individuals with symptomatic BD compared to HC. We observed a significant difference in salivary cortisol levels between those with BD and healthy controls for the nighttime sample (10PM). We did not find an association between nighttime salivary cortisol with that night’s objective or subjective sleep. These findings contribute to the existing body of research investigating patterns and trends of cortisol levels throughout the day in those with psychiatric disorders compared to those without. While we, and others, have reported cortisol dysregulation in many psychiatric disorders, the biological basis for these differences is as yet unknown. Further research is needed to parse out how the dysregulation occurs, what effects it has on symptomology and outcomes, and whether these observed trends could be exploited therapeutically for the management and treatment of BD.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants and families for generously being part of this project. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and College of Medicine.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences [KL2 TR000126].

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics

The research presented here was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All research was also approved by the Penn State University College of Medicine institutional review board (IRB Protocol: 39364EP). Written consent was obtained from all human participants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Faravelli C, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA. 1996. 1996 Jul 24–31;276(4):293–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, Kessler RC, Lee S, Sampson NA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Archives of general psychiatry. 2011. Mar;68(3):241–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordovez FJA, McMahon FJ. The genetics of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2020. Mar;25(3):544–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, Dean OM, Giorlando F, Maes M, et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011. Jan;35(3):804–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottlieb JF, Benedetti F, Geoffroy PA, Henriksen TEG, Lam RW, Murray G, et al. The chronotherapeutic treatment of bipolar disorders: A systematic review and practice recommendations from the ISBD task force on chronotherapy and chronobiology. Bipolar disorders. 2019. Dec;21(8):741–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrer A, Labad J, Salvat-Pujol N, Monreal JA, Urretavizcaya M, Crespo JM, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis-related genes and cognition in major mood disorders and schizophrenia: a systematic review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020. Mar 18;101:109929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charmandari E, Achermann JC, Carel JC, Soder O, Chrousos GP. Stress response and child health. Science signaling. 2012. Oct 30;5(248):mr1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lupien SJ, Leon Md, Santi Sd, Convit A, Tarshish C, Nair NPV, et al. Cortisol levels during human aging predict hippocampal atrophy and memorydeficits. Nature Neuroscience. 1998. 1998–05-01;1(1):69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turnbull AV, Rivier CL. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by cytokines: actions and mechanisms of action. Physiol Rev. 1999. Jan;79(1):1–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibuya I, Nagamitsu S, Okamura H, Ozono S, Chiba H, Ohya T, et al. High correlation between salivary cortisol awakening response and the psychometric profiles of healthy children. Biopsychosoc Med. 2014. p. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frodl T, O’Keane V. How does the brain deal with cumulative stress? A review with focus on developmental stress, HPA axis function and hippocampal structure in humans. Neurobiology of disease. 2013. Apr;52:24–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pruessner JC, Wolf OT, Hellhammer DH, Buske-Kirschbaum A, von Auer K, Jobst S, et al. Free cortisol levels after awakening: a reliable biological marker for the assessment of adrenocortical activity. Life sciences. 1997;61(26):2539–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hucklebridge F, Hussain T, Evans P, Clow A. The diurnal patterns of the adrenal steroids cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in relation to awakening. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005. Jan;30(1):51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weitzman ED, Fukushima D, Nogeire C, Roffwarg H, Gallagher TF, Hellman L. Twenty-four hour pattern of the episodic secretion of cortisol in normal subjects. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1971. Jul;33(1):14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cervantes P, Gelber S, Kin FN, Nair VN, Schwartz G. Circadian secretion of cortisol in bipolar disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001. Nov;26(5):411–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girshkin L, Matheson SL, Shepherd AM, Green MJ. Morning cortisol levels in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014. Nov;49:187–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamali M, Saunders EF, Prossin AR, Brucksch CB, Harrington GJ, Langenecker SA, et al. Associations between suicide attempts and elevated bedtime salivary cortisol levels in bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2012. Feb;136(3):350–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deshauer D, Duffy A, Meaney M, Sharma S, Grof P. Salivary cortisol secretion in remitted bipolar patients and offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar disorders. 2006. Aug;8(4):345–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daban C, Vieta E, Mackin P, Young AH. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and bipolar disorder. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2005. Jun;28(2):469–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young AH, Gallagher P, Watson S, Del-Estal D, Owen BM, Ferrier IN. Improvements in neurocognitive function and mood following adjunctive treatment with mifepristone (RU-486) in bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004. Aug;29(8):1538–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson S, Gallagher P, Porter RJ, Smith MS, Herron LJ, Bulmer S, et al. A randomized trial to examine the effect of mifepristone on neuropsychological performance and mood in patients with bipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2012. Dec 1;72(11):943–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abell JG, Shipley MJ, Ferrie JE, Kivimäki M, Kumari M. Recurrent short sleep, chronic insomnia symptoms and salivary cortisol: A 10-year follow-up in the Whitehall II study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016. Jun;68:91–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holsboer F, von Bardeleben U, Steiger A. Effects of intravenous corticotropin-releasing hormone upon sleep-related growth hormone surge and sleep EEG in man. Neuroendocrinology. 1988. Jul;48(1):32–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Wittman AM, Zachman K, Lin HM, Vela-Bueno A, et al. Middle-aged men show higher sensitivity of sleep to the arousing effects of corticotropin-releasing hormone than young men: clinical implications. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2001. Apr;86(4):1489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castro-Diehl C, Diez Roux AV, Redline S, Seeman T, Shrager SE, Shea S. Association of Sleep Duration and Quality With Alterations in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary Adrenocortical Axis: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2015. Aug;100(8):3149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harvey AG, Schmidt DA, Scarnà A, Semler CN, Goodwin GM. Sleep-related functioning in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder, patients with insomnia, and subjects without sleep problems. Am J Psychiatry. 2005. Jan;162(1):50–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnamurthy V, Mukherjee D, Reider A, Seaman S, Singh G, Fernandez-Mendoza J, et al. Subjective and objective sleep discrepancy in symptomatic bipolar disorder compared to healthy controls. Journal of affective disorders. 2018. Mar;229:247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukherjee D, Krishnamurthy VB, Millett CE, Reider A, Can A, Groer M, et al. Total sleep time and kynurenine metabolism associated with mood symptom severity in bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorders. 2018. 02;20(1):27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saunders EF, Reider A, Singh G, Gelenberg AJ, Rapoport SI. Low unesterified:esterified eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) plasma concentration ratio is associated with bipolar disorder episodes, and omega-3 plasma concentrations are altered by treatment. Bipolar disorders. 2015. Nov;17(7):729–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. The British journal of social and clinical psychology. 1967. Dec;6(4):278–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1978. Nov;133:429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman EG, Hedeker DR, Janicak PG, Peterson JL, Davis JM. The Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania (CARS-M): development, reliability, and validity. Biol Psychiatry. 1994. Jul 15;36(2):124–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrow JS, Webster J. Quetelet’s index (W/H2) as a measure of fatness. International journal of obesity. 1985;9(2):147–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989. May;28(2):193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthews EE, Schmiege SJ, Cook PF, Berger AM, Aloia MS. Adherence to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI) among women following primary breast cancer treatment: a pilot study. Behav Sleep Med. 2012;10(3):217–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruiter Petrov ME, Lichstein KL, Huisingh CE, Bradley LA. Predictors of adherence to a brief behavioral insomnia intervention: daily process analysis. Behav Ther. 2014. May;45(3):430–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oster H, Challet E, Ott V, Arvat E, de Kloet ER, Dijk DJ, et al. The Functional and Clinical Significance of the 24-Hour Rhythm of Circulating Glucocorticoids. Endocr Rev. 2017. 02;38(1):3–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Liao D, Bixler EO. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration: the most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2013. Aug;17(4):241–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melo MC, Garcia RF, Linhares Neto VB, Sá MB, de Mesquita LM, de Araújo CF, et al. Sleep and circadian alterations in people at risk for bipolar disorder: A systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2016. 12;83:211–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ng TH, Chung KF, Lee CT, Yeung WF, Ho FY. Eveningness and Its Associated Impairments in Remitted Bipolar Disorder. Behav Sleep Med. 2016. 2016 Nov-Dec;14(6):650–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pinho M, Sehmbi M, Cudney LE, Kauer-Sant’anna M, Magalhães PV, Reinares M, et al. The association between biological rhythms, depression, and functioning in bipolar disorder: a large multi-center study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016. Feb;133(2):102–08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Linkowski P, Kerkhofs M, Van Onderbergen A, Hubain P, Copinschi G, L’Hermite-Balériaux M, et al. The 24-hour profiles of cortisol, prolactin, and growth hormone secretion in mania. Archives of general psychiatry. 1994. Aug;51(8):616–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]