Abstract

Objective

This cross-sectional study explores the serial multiple mediation of the correlation between internet addiction and depression by social support and sleep quality of college students during the COVID-19 epidemic.

Methods

We enrolled 2,688 students from a certain university in Wuhu, China. Questionnaire measures of internet addiction, social support, sleep quality, depression and background characteristics were obtained.

Results

The prevalence of depression, among 2,688 college students (median age [IQR]=20.49 [20.0, 21.0] years) was 30.6%. 32.4% of the students had the tendency of internet addiction, among which the proportion of mild, moderate and severe were 29.8%, 2.5% and 0.1%, respectively. In our normal internet users and internet addiction group, the incidence of depression was 22.6% and 47.2%, respectively. The findings indicated that internet addiction was directly related to college students’ depression and indirectly predicted students’ depression via the mediator of social support and sleep quality. The mediation effect of social support and sleep quality on the pathway from internet addiction to depression was 41.97% (direct effect: standardized estimate=0.177; total indirect effect: standardized estimate=0.128). The proposed model fit the data well.

Conclusion

Social support and sleep quality may continuously mediate the link between internet addiction and depression. Therefore, the stronger the degree of internet addiction, the lower the individual’s sense of social support and the worse the quality of sleep, which will ultimately the higher the degree of depression. We recommend strengthening monitoring of internet use during the COVID-19 epidemic, increasing social support and improving sleep quality, so as to reduce the risk of depression for college students.

Keywords: Addictive disorder, Depressive disorder, Sleep disorder, Epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

An outbreak of a respiratory disease of unknown cause was reported in Wuhan, capital of China’s Hubei province, in December 2019 [1]. The continued spread of the epidemic, strict quarantine measures and delays in colleges and universities throughout the country are expected to affect the mental health of college students [2]. During the COVID-19 epidemic, among the 2,031 participants, 48.14% (n=960) of American college students showed moderate to severe depression [3]. And the prevalence of depressive symptoms in Chinese college students was 12.2% (95% CI: 11.9%–12.5%) [4]. Data from the American College Health Association’s National College Health Assessment, college counseling centers [5,6], and individual college campuses [7] all indicated that rates of depression disorders are high and, in many cases, increasing. A meta-analysis of 39 studies conducted from 1997 to 2015, including 32,694 college students, showed that the overall prevalence of depression among Chinese college students was 23.8% (95% CI: 19.9%–28.5%) [8]. Therefore, early detection and effective intervention measures should be taken to reduce college students’ depression and its risk factors.

The internet has become a key resource in society and everyday life, and internet addiction is a another worldwide public health problem. During the COVID-19 epidemic, 46.8% of subjects reported increased dependence on internet use, while 16.6% of subjects had longer internet use time [9]. Internet addiction was associated with social support [10] and psychological disorders such as insomnia, stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms [3]. A body of studies have shown that people who are addicted to the internet would have a higher risk of depression [11,12]. Despite previous study findings that claim internet addiction may be strongly related to depression, the underlying mediating mechanism (i.e., how internet addiction influences depression) remain unclear, especially among Chinese college students.

The substantial association between both internet addiction and depression and sleep quality and social support may shed insights to our understanding about the mechanism. A systematic review of current findings in Western countries reported a strong link between social support and depression prevention [13]. Deficits in parental and classmate support may play a greater role in contributing to adolescent depression as compared to deficits in peer support [14]. Similarly, college students with sleep problems are more likely to have symptoms of depression. A study on sleep quality indicated that college students with poor sleep quality are related to increased internet access and poor social support [15]. Given their strong association with both internet addiction and depression, social support and sleep quality may be the main mediators of the relationship between internet addiction and depression. If so, it will help close the causal gap between internet addiction and depression.

Previous studies have shown that social support can potentially mediate the relationship between internet addiction and sleep quality, indicating that social support and sleep quality can sequentially mediate the effect of internet addiction on depression in college students. Thus, social support is accepted as a mediator on the relationship between internet addiction and sleep quality. As there were strong associations as well as strong predictor effects between internet addiction, social support, sleep quality and depression, the following mediation model may be implied that college students with internet addiction may experience low social support before developing poor sleep quality and, consequently, develop depression symptoms.

Although studies have shown that there are independent and strong links between psychological disorders, theoretical models are needed to explain how internet addiction affects depression. Therefore, this study investigated a serial multiple mediation model on the basis of previous research results. The aim was to investigate the prevalence for depression among college student during the COVID-19 epidemic; to test the association between internet addiction, social support, sleep quality, and depression; to explore the serial multiple mediation effect of social support and sleep quality on the association between internet addiction and depression.

METHODS

Participants and recruitment

During the epidemic, a paper questionnaire survey was conducted among all students from a university in Wuhu, China. Inclusion criteria: college students who were in school during the epidemic period; college students who volunteered to take part in the survey. Exclusion criteria: college students with other psychiatric disorders. In this study, a total of 2,790 students were surveyed, and 2,702 valid questionnaires were returned, with a recovery rate of 96.85%. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study, 2,688 questionnaires were included in this study, with an effective rate of 96.34%.

The study was approved by the Psychological Research Ethics Committee of Wannan Medical College (Batch number for ethical review: LL-20131401). Prior to the formal investigation, the investigators received training in a uniform manner, with a clear understanding of the purpose, method and importance of the survey. And informed consent was given to the students who were surveyed. During the completion of the questionnaire, the investigators informed them of the significance and confidentiality of the investigation and reminded them of the precautions.

Measures

Background characteristics

The following background characteristics were analyzed: sex, age, nationality, disease history, number of exercises per week, father’s education, mother’s education, father’s occupations, mother’s occupations, relationship with parents, parents’ expectations of their children, et al.

Self-rating depression scale (SDS)

The Depression Self-Rating Scale was compiled by Zung et al. [16] with a total of 20 items. Each item is scored on a scale of 1 to 4. The cumulative score of each item is the total rough score. The integer part of the total rough score multiplied by 1.25 is recorded as the standard total score. The higher the standard total score, the higher the degree of depression. If the standard total score is higher than 50, it is assessed as having symptoms of depression (Cronbach’s α=0.84). SDS continuous scale scores were used for path analysis.

Internet addiction scale (IAS)

IAS was established by Young et al. [17] to investigate the degree of use and dependence on the network. The scale has a total of 20 questions, the answer is “almost no” counts 0 points, “occasionally” counts 1 point, “Sometimes” counts 2 points, “often” counts 3 points, “always” counts 4 points. If the total score exceeds 40 points, it was judged to be indulged on the internet (Cronbach’s α=0.81). IAS continuous scale scores were used for path analysis.

Social support rating scale (SSRS)

This study uses the SSRS compiled by Shui-yuan Xiao, the scale has a total of 10 questions, divided into three dimensions: objective support, subjective support, and support utilization. The higher the total score, the higher the individual’s sense of social support (Cronbach’s α=0.88). SSRS continuous scale scores were used for path analysis.

Pittsburgh sleep quality index scale (PSQI)

The PSQI scale revised by Chinese scholar Xian-chen Liu and others was adopted. The scale includes seven dimensions of subjective sleep quality, time to fall asleep, sleep time, sleep efficiency, sleep disorders, hypnotic drugs and daytime dysfunction. There are 18 items in total, each item has a 4-level score, and the total score ranges from 0 to 21 points. The higher the total score, the worse the quality of sleep (Cronbach’s α=0.82). PSQI continuous scale scores were used for path analysis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were first conducted of background characteristics and the prevalence of internet addiction, sleep disorders and depression and the score of social support. As the distribution of age was skewed, this continuous variable was described using the median (inter-quartile range [IQR]).

Multi-variable linear regression was then performed to examine the association between background characteristics and internet addiction, social support, sleep quality, depression. Moreover, pairwise correlation analysis of measurements was used to test the relationships among the variables.

The serial multiple mediation hypothesis for internet addiction, social support, sleep quality, and depression was tested using Preacher and Hayes’s method [18]. Bootstrapping analysis using 5,000 resamples to test the significance of the mediation effect [19]. The Bootstrap method provides an estimate of the indirect influence, tests whether the influence is statistically significant, and also determines the confidence interval of the point estimate, which tends to supplement the limitations of the causal step method. This method shows that if the correction bias confidence interval does not contain zero, the mediating effect is significant.

We used IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to conduct the descriptive analysis, logistic regression, and pairwise correlation analysis, and used PROCESS program developed by Hayes to conduct the path analysis. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The study included 2688 undergraduates (median age [IQR]=20.49 [20.0, 21.0] years). Most students are Han nationality (96.5%). 32.4% of the students had the tendency of internet addiction, among which the proportion of mild, moderate and severe were 29.8%, 2.5% and 0.1%, respectively. In our general study samples and internet addiction group, the incidence of depression was 22.6% and 47.2%, respectively. The social support score for all participants was 38.70±5.94. The survey showed that 12.1% of the students had sleep disorders, and the mean score of PSQI was 4.34±2.80. In this survey, 822 (30.6%) participants had depressive symptoms, of which 600 (22.3%) had mild symptoms, 201 (7.5%) had moderate symptoms and 21 (0.8%) had severe symptoms.

Multi-variable linear regression

The results from multi-variable linear regression models of the relationship of the background characteristics with internet addiction, social support, sleep quality, and depressive symptoms are tabled in Table 1. Overall, males are more likely than females to have the tendency of internet addiction (b= -1.089; BCa 95% CI: -2.019, -0.159). The better the parents’ relationship (b=-2.203; BCa 95% CI: -2.696, -1.711), and the more times they exercised (b=-0.962; BCa 95% CI: -1.378, -0.546), the less likely the students were to become addicted to the internet. The better the relationship between parents (b=1.766; BCa 95% CI: 1.488, 2.043) and the more times students exercise (b=0.493; BCa 95% CI: 0.259, 0.728), the higher the score of social support. The higher the parents’ expectations for their children, the lower the scores for social support (b=-0.880; BCa 95% CI: -1.214, -0.547).The sleep quality of female is worse than that of male (b=0.481; BCa 95% CI: 0.229, 0.733). The better the parents’ relationship (b=-0.668; BCa 95% CI: -0.801, -0.535),and the more times they exercised (b=-0.195; BCa 95% CI: -0.308, -0.083), the better the sleep quality of students. Female are more likely to have depressive symptoms than male (b=1.268; BCa 95% CI: 0.424, 2.112). The degree of parents’ relationship (b=-2.695; BCa 95% CI: -3.142, -2.249) and the times of exercise (b=-0.748; BCa 95% CI: -1.125, -0.371) were negatively correlated with depressive symptoms.

Table 1.

Multi-variable linear regression models of students’ characteristics with internet addiction, social support, sleep quality, and depressive

| Characteristics | Internet addiction |

Social support |

Sleep quality |

Depression |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | BCa 95% CI | b | BCa 95% CI | b | BCa 95% CI | b | BCa 95% CI | |

| Age | -0.048 | -0.458, 0.362 | 0.127 | -0.104, 0.358 | 0.014 | -0.097, 0.125 | -0.085 | -0.456, 0.287 |

| Sex (ref: male) | -1.089*§ | -2.019, -0.159 | 0.452 | -0.073, 0.977 | 0.481‡§ | 0.229, 0.733 | 1.268†§ | 0.424, 2.112 |

| Father’s education | -0.159 | -0.651, 0.333 | -0.097 | -0.375, 0.180 | 0.012 | -0.121, 0.146 | 0.040 | -0.406, 0.487 |

| Mother’s education | 0.112 | -0.397, 0.620 | -0.265 | -0.552, 0.022 | -0.007 | -0.145, 0.131 | 0.016 | -0.445, 0.478 |

| Father’s occupations | -0.060 | -0.195, 0.074 | -0.012 | -0.088, 0.064 | -0.016 | -0.052, 0.021 | -0.054 | -0.176, 0.067 |

| Mother’s occupations | -0.056 | -0.190, 0.078 | 0.007 | -0.069, 0.082 | -0.014 | -0.050, 0.022 | 0.009 | -0.112, 0.131 |

| The relationship between parents | -2.203ठ| -2.696, -1.711 | 1.766ठ| 1.488, 2.043 | -0.668ठ| -0.801, -0.535 | -2.695ठ| -3.142, -2.249 |

| Parents’ expectations of their children | -0.336 | -0.927, 0.256 | -0.880‡§ | -1.214, -0.547 | -0.137 | -0.297, 0.024 | 0.359 | -0.178, 0.896 |

| Physical activity | -0.962†§ | -1.378, -0.546 | 0.493‡§ | 0.259, 0.728 | -0.195‡§ | -0.308, -0.083 | -0.748‡§ | -1.125, -0.371 |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001;

Statistically significant associations.

b, unstandardized coefficient; BCa, bias corrected and accelerated: 5,000 bootstrap samples; CI, confidence interval

Pairwise correlation analysis

Table 2 shows the results of the pairwise correlation analysis. There were positive and significant correlations among internet addiction, sleep quality, depression, but social support is significantly negatively correlated with internet addiction, sleep quality and depression (p<0.01).

Table 2.

Questionnaire scores and pairwise correlation analysis (N=2,688)

| Variable | Mean±SD | Internet addiction | Social support | Sleep quality | Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet addiction | 36.20±10.31 | 1 | |||

| Social support | 38.70±5.94 | -0.261* | 1 | ||

| Sleep quality | 4.34±2.80 | 0.338* | -0.289* | 1 | |

| Depression | 45.05±9.49 | 0.363* | -0.339* | 0.464* | 1 |

p<0.01.

SD, standard deviation

Mediating effect test

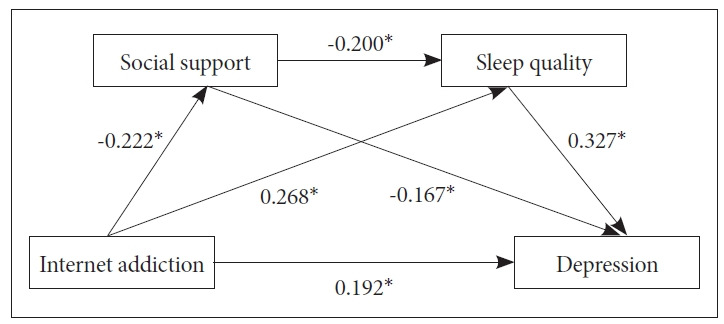

As shown in Figure 1, using the SPSS macro program Process compiled by Hayes to analyze the mediating effect, under the condition of controlling age, sex, father’s education, mother’s education, father’s occupations, mother’s occupations, the relationship between parents, parents’ expectations of their children and physical activity analyze the mediating effect of social support and sleep quality on the relationship between internet addiction and depression in college students. Regression analysis showed, internet addiction could positively predict depressive symptoms (β=0.192, p<0.001). After the inclusion of mediator variables, internet addiction could not only negatively predict social support (β=-0.222, p<0.001), but also positively predict sleep quality (β=0.268, p<0.001). Similarly, social support not only negatively predicted sleep quality (β=-0.200, p<0.001), but also depression (β=-0.167, p<0.001). In other words, the higher the degree of internet addiction, the lower the social support received, the poorer the quality of sleep, and the more severe the depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Path analysis of internet addiction, social support, sleep quality and depression among college students (N=2,688). Age, sex, father’s education, mother’s education, father’s occupations, mother’s occupations, the relationship between parents, parents’ expectations of their children and physical activity were adjusted as covariates in the path analysis. Parameters displayed are standardized estimates of the direct effect on each pathway.

*p<0.001.

Path analysis

As shown in Table 3, there was a significant total effect (Std. estimate=0.305) of internet addiction on depression. The direct effect (Std. estimate=0.177) of internet addiction on depression was also significant. In addition, the indirect effects of internet addiction on depression through social support (Std. estimate=0.034) and through sleep quality (Std. estimate=0.081) and through social support then sleep quality (Std. estimate=0.013) were significant. Overall, the mediating effect of social support and sleep quality were 41.97% (0.128/0.305) in the pathway from internet addiction to depression.

Table 3.

Results of path analysis (N=2,688)

| Paths | Std. estimate | SE | Bootstrapping 95% CI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower 2.5% | Upper 2.5% | ||||||

| Depression | |||||||

| Total effect | 0.305 | 0.016 | 0.273 | 0.337 | |||

| Direct effect | 0.177 | 0.016 | 0.145 | 0.208 | |||

| Indirect effect | |||||||

| Total indirect effect | 0.128 | 0.009 | 0.110 | 0.147 | |||

| Specific indirect effect | |||||||

| Internet addiction → Social support → Depression | 0.034 | 0.005 | 0.025 | 0.044 | |||

| Internet addiction → Sleep quality→ Depression | 0.081 | 0.007 | 0.066 | 0.096 | |||

| Internet addiction → Social support → Sleep quality→ Depression | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.010 | 0.017 | |||

| Coefficient | |||||||

| Internet addiction → Social support | -0.222 | 0.011 | -0.148 | -0.107 | |||

| Social support → Sleep quality | -0.200 | 0.009 | -0.112 | -0.077 | |||

| Sleep quality → Depression | 0.327 | 0.060 | 0.988 | 1.223 | |||

Std. estimate, standardized estimate; SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval

DISCUSSION

This study not only provides epidemiological data on internet addiction, social support, sleep quality, and depression in college students during the COVID-19 epidemic, but also elucidates their relationships and underlying mechanisms using a serial multiple mediation model. In our general study samples and internet addiction group, the incidence of depression was 22.6% and 47.2%, respectively. Compared with back-toschool college students who use the internet normally, individuals with internet addiction are more likely to develop depressive symptoms. These results are consistent with the results of a previous meta-analysis of the association between internet addiction and psychiatric co-morbidity [20], which found that internet addiction is closely related to depressive symptoms.

The present findings identified significant relationships between internet addiction, social support, sleep quality, and depression, and strongly suggest that more efforts are needed to monitor college students’ internet use and prevent sleep disorders and improve social support to reduce the occurrence of depression symptoms. Our results show a mediating effect of social support on the association between internet addiction and sleep quality. Social support is usually defined as the perceived comfort, care, respect, or help a person receives from others. College students may be addicted to the internet, which reduces the opportunity to communicate and accompany others, so that they receive very little social support. However, studies have reported that supportive ties were positively related to sleep quality [21]. Judging from the available evidence, it is reasonable to mediate the relationship between internet addiction and sleep quality. Besides, our model tested the bidirectional relationship between internet addiction and sleep quality with a statistically significant result. However, we found that in the correlation between internet addiction, sleep quality and depression, sleep quality is a stronger mediator than internet addiction, which is consistent with the previous literature.

This is the first study to examine a serial multiple mediation model of the associations between internet addiction and social support and sleep quality and depression of college students returning to school during the COVID-19 epidemic. The mediation model demonstrated that internet addiction was sequentially correlated with low social support in the first step, and further positively affected the onset of poor sleep quality, which was associated with a greater risk of depression. The overall intermediary effect of this approach accounts for 41.97%. Furthermore, both social support and sleep quality significantly modulated the pathway of depression, highlighting the key mediating roles of social support and sleep quality in the overall model. The results are consistent with a study by Grey et al. [22] on the effect of cognitive social support on sleep and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Students with internet addiction may spend considerable time online, which may affect their sleep-wake plan and develop sleep disorders, including insomnia and as many previous studies have shown, this leads to the development of depressive symptoms [23]. Therefore, better control of internet use by college students, improvement of social support and improvement of sleep quality are the core of preventing depression during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, the findings of this study can be interpreted in the light of study limitations. The risk behaviors and their association being studied cross-sectionally, it is impossible to infer directionality in the relationship among internet addiction, social support and sleep quality; whether depressive symptoms are secondary to internet addiction, social support, and sleep quality, or it predicts the three factors. Alternatively, sleep problem and social support could serve as outcome of internet addiction and depressive symptoms theoretically. Considering the purpose of the research, these approaches have not been tested in this study. Recently, Fazeli et al. [24] observed that psychological distress (i.e., depression, anxiety, and stress) served as a strong mediator in the association between internet gaming disorder and insomnia and quality of life during the COVID-19 epidemic. In future studies, the measurement of predictive factors and mediating factors is higher than the outcome variable, which will provide stronger evidence for the path of the development of students’ depressive symptoms. Similarly, since the research method is a questionnaire survey, this research may be affected by social expectations bias, that is, students’ responses may be influenced by what they consider socially acceptable, rather than providing actual practice. Another limitation of this study is the questionnaire-based diagnosis of depression and sleep problem. In addition, this study did not completely rule out other psychiatric problems, such as ADHD. So if these limitations can be resolved, it will have a great change to the mediation model.

In conclusions, this is the first study to examine a serial multiple mediation model of the associations between internet addiction and social support and sleep quality and depression of college students returning to school during the COVID-19 epidemic. We found a serial multiple mediation effect of social support and sleep quality on the pathway from internet addiction to depression. The findings indicated that the stronger the degree of internet addiction, the lower the individual’s sense of social support and the worse the quality of sleep, which will ultimately the higher the degree of depression. We recommend that interventions for internet addiction, social support and sleep quality should be strengthened to prevent depression among college students returning to school during the COVID-19 epidemic.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the participants for their contributions to this study.

Footnotes

Availability of Data and Material

The data and materials used in this study can be obtained from the corresponding authors and will be provided upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Minmin Jiang, Ying Zhao. Data curation: Minmin Jiang, Ying Zhao. Formal analysis: Minmin Jiang, Ying Zhao. Funding acquisition: Yingshui Yao, Yuelong Jin, Yan Chen. Investigation: Minmin Jiang, Ying Zhao, Jing Wang, Long Hua, Yan Chen. Methodology: Minmin Jiang, Ying Zhao, Yan Chen. Project administration: Yingshui Yao, Yuelong Jin. Resources: Yan Chen, Yingshui Yao, Yuelong Jin. Software: Minmin Jiang, Ying Zhao. Supervision: Yan Chen, Yingshui Yao, Yuelong Jin. Validation: Minmin Jiang,Ying Zhao. Visualization: Minmin Jiang, Ying Zhao, Jing Wang, Yan Chen. Writing—original draft: Minmin Jiang, Ying Zhao. Writing—review & editing: Minmin Jiang, Ying Zhao.

Funding Statement

Innovative Leading Talents of the Fifth Batch of Provincial Special Support Plan of Anhui Province (T000516); Major natural science research Projects in Universities of Anhui Province (NO. KJ2020ZD69); Anhui Province Health Soft Science Research Project (NO. 2020WR04005); Anhui Provincial Quality Engineering Project of Higher Education Institutions (NO.2015zjjh017).

REFERENCES

- 1.Yang T, Yu L, Oliffe JL, Jiang S, Si Q. Regional contextual determinants of Internet addiction among college students: a representative nation-wide study of China. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27:1032–1037. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang S, Tian Y, Sui Y, Zhang D, Shi J, Wang P, et al. Relationships between social support, loneliness, and internet addiction in Chinese postsecondary students: a longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1707. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Younes F, Halawi G, Jabbour H, El Osta N, Karam L, Hajj A, et al. Internet addiction and relationships with insomnia, anxiety, depression, stress and self-esteem in university students: a cross-sectional designed study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chi X, Liu X, Guo T, Wu M, Chen X. Internet addiction and depression in Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:816. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchanan JL. Prevention of depression in the college student population: a review of the literature. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2012;26:21–42. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscomb M, Clarahan M, et al. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajduk M, Heretik A, Jr, Vaseckova B, Forgacova L, Pecenak J. Prevalence and correlations of depression and anxiety among Slovak college students. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2019;120:695–698. doi: 10.4149/BLL_2019_117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng C, Li AY. Internet addiction prevalence and quality of (real) life: a meta-analysis of 31 nations across seven world regions. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17:755–760. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Y, Li Y, Bao Y, Meng S, Sun Y, Schumann G, et al. Brief report: increased addictive internet and substance use behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Am J Addict. 2020;29:268–270. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mo PKH, Chan VWY, Chan SW, Lau JTF. The role of social support on emotion dysregulation and Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: a structural equation model. Addict Behav. 2018;82:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain A, Sharma R, Gaur KL, Yadav N, Sharma P, Sharma N, et al. Study of Internet addiction and its association with depression and insomnia in university students. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020;9:1700–1706. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1178_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi SW, Kim DJ, Choi JS, Ahn H, Choi EJ, Song WY, et al. Comparison of risk and protective factors associated with smartphone addiction and Internet addiction. J Behav Addict. 2015;4:308–314. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gariépy G, Honkaniemi H, Quesnel-Vallée A. Social support and protection from depression: systematic review of current findings in Western countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209:284–293. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.169094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auerbach RP, Bigda-Peyton JS, Eberhart NK, Webb CA, Ho MH. Conceptualizing the prospective relationship between social support, stress, and depressive symptoms among adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2011;39:475–487. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9479-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng SH, Shih CC, Lee IH, Hou YW, Chen KC, Chen KT, et al. A study on the sleep quality of incoming university students. Psychiatry Res. 2012;197:270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zung WW, Richards CB, Short MJ. Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic. Further validation of the SDS. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;13:508–515. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01730060026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young K, Pistner M, O’Mara J, Buchanan J. Cyber disorders: the mental health concern for the new millennium. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1999;2:475–479. doi: 10.1089/cpb.1999.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu QJ, Cui CR. [Genetic transformation of OSISAP1 gene to onion (Allium cepa L.) mediated by amicroprojectile bombardment] Zhi Wu Sheng Li Yu Fen Zi Sheng Wu Xue Xue Bao. 2007;33:188–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho RC, Zhang MW, Tsang TY, Toh AH, Pan F, Lu Y, et al. The association between Internet addiction and psychiatric co-morbidity: a metaanalysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:183. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent RG, Uchino BN, Cribbet MR, Bowen K, Smith TW. Social Relationships and Sleep Quality. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49:912–917. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9711-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grey I, Arora T, Thomas J, Saneh A, Tohme P, Abi-Habib R. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113452. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fazeli S, Mohammadi Zeidi I, Lin CY, Namdar P, Griffiths MD, Ahorsu DK, et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress mediate the associations between Internet gaming disorder, insomnia, and quality of life during the COVID-19 outbreak. Addict Behav Rep. 2020;12:100307. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]