Abstract

Porcine enteric calicivirus (PEC) causes diarrhea and intestinal lesions in pigs. PEC strain Cowden grows to low to moderate titers in cell culture but only with the addition of intestinal contents from uninfected gnotobiotic pigs (W. T. Flynn and L. J. Saif, J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:206–212, 1988; A. V. Parwani, W. T. Flynn, K. L. Gadfield, and L. J. Saif, Arch. Virol. 120:115–122, 1991). Cloning and sequence analysis of the PEC Cowden full-length genome revealed that it is most closely related genetically to the human Sapporo-like viruses. In this study, the complete PEC capsid gene was subcloned into the plasmid pBlueBac4.5 and the recombinant baculoviruses were identified by plaque assay and PCR. The PEC capsid protein was expressed in insect (Sf9) cells inoculated with the recombinant baculoviruses, and the recombinant capsid proteins self- assembled into virus-like particles (VLPs) that were released into the cell supernatant and purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation. The PEC VLPs had the same molecular mass (58 kDa) as the native virus capsid and reacted with pig hyperimmune and convalescent-phase sera to PEC Cowden in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blotting. The PEC capsid VLPs were morphologically and antigenically similar to the native virus by immune electron microscopy. High titers (1:102,400 to 204,800) of PEC-specific antibodies were induced in guinea pigs inoculated with PEC VLPs, suggesting that the VLPs could be useful for future candidate PEC vaccines. A fixed-cell ELISA and VLP ELISA were developed to detect PEC serum antibodies in pigs. For the fixed-cell ELISA, Sf9 cells were infected with recombinant baculoviruses expressing PEC capsids, followed by cell fixation with formalin. For the VLP ELISA, the VLPs were used for the coating antigen. Our data indicate that both tests were rapid, specific, and reproducible and might be used for large-scale serological investigations of PEC antibodies in swine.

Caliciviruses in the Caliciviridae family are causative agents of a wide spectrum of diseases in their respective hosts (11). According to recent reports, human caliciviruses (HuCV), including Norwalk-like viruses (NLVs) and Sapporo-like viruses (SLVs), are the leading cause of food- and waterborne acute gastroenteritis in humans (7, 30, 37, 38). The enteric caliciviruses from cattle, swine, and mink are associated with gastroenteritis in their respective hosts (2, 15, 36; K. W. Theil and C. M. McCloskey, Abstr. CRWAD 1995, abstr. 110, 1995). These animal enteric caliciviruses are closely related genetically to their human counterparts, but are genetically and antigenically distinct from the cultivable animal caliciviruses, the vesiviruses (4, 14, 28).

Caliciviruses possess a positive, single-stranded RNA genome 7.3 to 8.4 kb in length and a single structural capsid protein of 56 to 71 kDa (6, 25). For NLVs and vesiviruses, the RNA genome is composed of three open reading frames (ORFs) and the capsid protein is encoded by ORF2 (6, 11, 25). In SLVs and lagoviruses, the capsid gene is fused to and contiguous with the polyprotein gene in the ORF1 (6, 11, 25). However, it is thought that during viral replication the capsid protein is encoded primarily by a subgenomic RNA that overlaps the genomic C-terminal region and contains the capsid protein gene and a small ORF at the 3′ end encoding a minor structural protein (6, 10, 41). This mechanism for expression of the viral capsid protein may be shared among caliciviruses. Because HuCV are uncultivable in cell culture and are genetically diverse, epidemiological investigations of human infections were impeded until recombinant calicivirus capsids which assembled into virus-like particles (VLPs) were produced and used to develop serologic diagnostic assays (12, 19, 22, 23). The baculovirus expression system has proven very efficient for the production of recombinant capsids of NLVs such as Norwalk virus (NV), Mexico virus (MxV), Toronto virus, Hawaii virus, Grimsby virus, and also the rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV), a lagovirus causing systemic hemorrhage and liver necrosis in rabbits (5, 13, 16, 21, 22, 26, 27). Interestingly, the recombinant capsid proteins expressed in baculovirus self-assembled into VLPs which were morphologically and antigenically similar to native viruses. The recombinant capsids or VLPs not only induced antibodies to native virus particles in guinea pigs and mice (NV and Mexico VLPs) (21, 22) or human volunteers (NV) (1), but also provided protective immunity in rabbits against RHDV challenge (26). In addition, the production of recombinant NV (rNV) VLPs has aided in understanding NV structure (35) and in studying some early events (attachment and entry) in the binding of rNV VLPs to cultured human and animal cell lines (39).

The SLVs are genetically related to but antigenically distinct from NLVs based on enzyme immunoassys, solid-phase immunoelectron microscopy (IEM), and capsid sequence analysis (18, 20, 23, 24, 25). Although the recombinant capsid protein genes of several human SLVs, including Sapporo virus and two other strains, Houston/86 and Houston/90, were expressed in baculovirus, the yield of VLPs was low in comparison with that of NV VLPs (24, 32). It is unclear why recombinant human SLV capsid genes aren't expressed efficiently in the baculovirus expression system (24).

Porcine enteric caliciviruses (PEC) cause diarrhea and intestinal lesions in pigs (9, 36). The PEC Cowden strain is the prototype strain for PEC and it was recently characterized as a member in the SLV genus (14). The PEC Cowden strain can be grown in cell culture but requires the addition to the medium of intestinal content from uninfected gnotobiotic pigs, which is expensive and in limited supply (8, 34). Because of the genetic and antigenic diversity among SLVs (14, 18, 31, 32), the currently available diagnostic assays based on VLPs for human SLVs may not be applicable for enteric SLVs in animals unless these viruses are proven to be antigenically related. Thus it is necessary to develop diagnostic assays using VLPs specific for the prototype PEC Cowden strain or other genetically and antigenically representative strains from swine for evaluation of caliciviral infections in swine. Furthermore, the antigenic relationships between human SLVs and animal SLVs can be evaluated with such VLPs and the corresponding antisera.

We cloned the capsid gene of PEC Cowden and studied its expression in the baculovirus expression system. The recombinant capsid proteins were expressed in baculovirus and self-assembled into VLPs that were morphologically and antigenically similar to the native virus. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using PEC VLPs as the coating antigen and a fixed-cell ELISA using recombinant baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells were developed and compared for the detection of antibodies against PEC in swine sera.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of recombinant baculovirus transfer vectors and generation of baculovirus recombinants.

The tissue culture-adapted PEC Cowden was propagated in the porcine kidney cell line, LLC-PK, as described previously (34), and the viral RNA was purified by using TRIzol (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.). The PEC capsid gene was amplified from the PEC RNA by using reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) with primers PEC70 (5′-TAA TACGACTCACTATAGG5131GTGTTCGTGATGGA5144-3′) and PEC12 (5′-7070TTGTTGCCCACCAAGGTA7053-3′) that were designed based on the genomic capsid sequence of PEC Cowden (14). The primer PEC70 included the bacteriophage T7 promoter sequence (italicized) at the 5′ end and the highly conserved 5′ sequence motif (underlined) of the predicted subgenomic RNA of PEC Cowden. The amplicon was first cloned into a pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and then subcloned into a baculovirus transfer vector, pBlueBac4.5 (Invitrogen), by using the EcoRI restriction enzyme site. The recombinant baculovirus transfer vector, the pBlueTC2-6, which contained the PEC full-length capsid gene in correct orientation, was used to cotransfect the insect (Spodoptera frugiperda) cells (Sf9) together with the linearized wild-type baculovirus DNA according to the instructions provided by the kit supplier. Recombinant baculoviruses containing the entire capsid gene were identified by three rounds of plaque purification and by PCR with PEC-specific primers and custom primers based on the vector sequence.

Production and purification of the PEC VLPs.

The plaque-purified viruses were used to infect Sf9 cells at a high multiplicity of infection (MOI, ∼10), and the cell cultures were harvested at 5 to 7 postinoculation days (PID). The harvested cells and supernatants were separated by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 50 min at 4°C. Both the supernatants and the cell lysates were examined for recombinant PEC (rPEC) capsids by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting with preexposure swine serum and hyperimmune swine serum against PEC Cowden. The peroxidase-labeled goat anti-pig immunoglobulin G (IgG) Fc reagent (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) was used as conjugate and TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was used as substrate for color development. The proteins in the polyacrylamide gels were also stained with Coomassie blue as previously described (22).

For purification of rPEC VLPs, Sf9 cells in 162-cm2 flasks or six-well plates (Corning Costar Corp., Cambridge, Mass.) were infected with recombinant baculoviruses at an MOI of 10 and harvested at PID 5 to 7. Cell cultures were sonicated twice on ice, 30 s each time. Supernatants were collected from the cell lysates after centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 50 min, and rPEC VLPs in the supernatants were concentrated by centrifugation through 40% sucrose cushions at 112,700 × g for 2 h. The resulting pellets were resuspended in 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer containing 0.15 M NaCl and 15 mM CaCl2, pH 6.5 (TNC). The rPEC VLPs were further purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation at 147,215 × g for 18 h at 4°C (22). To determine the density and composition of the rPEC VLPs, 0.35-ml fractions were collected from the CsCl gradients with a needle and syringe by perforating the cellulose nitrate tube and were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, Western blotting, and refractometry (to assess the density of each fraction). The recombinant proteins of 58 kDa (VLPs) were identified in a visible band in the middle of the CsCl gradients by electrophoretic and immunoblotting analyses. This fraction was collected, resuspended in TNC buffer, and centrifuged at 107,170 × g at 4°C for 2 h to remove the CsCl. The resulting pellets were resuspended in TNC buffer and examined by negative-stain IEM (36). The protein concentration was measured by using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). The purified VLPs identified were used as antigens to coat 96-well plates and to immunize guinea pigs as described below.

Determination of the dynamics of recombinant protein production in Sf9 cells.

Sf9 cells infected with recombinant baculoviruses or mock infected were harvested daily from PID 1 to 8. The supernatants were separated from the cell pellets by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 30 min. The cell pellets were suspended in cell lysis buffer, and the recombinant proteins in the cell lysates and supernatants were detected by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as well as an antigen (Ag) ELISA that is described below. For immunoblotting, the rPEC VLPs in the supernatants were concentrated either by centrifugation through 40% sucrose cushions or by precipitation with 8% polyethylene glycol followed by centrifugation for 30 min at 15,000 × g. The resulting pellets were dissolved in TNC buffer and adjusted to a volume equal to that of the cell pellet suspensions.

Production of hyperimmune antiserum in guinea pigs.

Two guinea pigs were first immunized with the rPEC VLPs (using a dose of 400 μg/guinea pig) mixed with Freund's complete adjuvant via subcutaneous injection followed by two booster injections 2 weeks apart of the same dose in Freund's incomplete adjuvant. The guinea pigs were bled 2 weeks after the last booster injection. The serum was collected and stored at −20°C until use.

Swine serum samples.

Preexposure (PID, 0), acute (PID, 1 to 7), and convalescent (PID, 21 to 28) phase serum samples were collected from gnotobiotic pigs orally inoculated with PEC Cowden (9). The preexposure pig sera were used as negative reference sera, the convalescent-phase sera were used as positive reference sera, and hyperimmune gnotobiotic pig antisera to porcine rotavirus and transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE) coronavirus sera were also used as negative controls for evaluation of the specificity of ELISA. Field sera were collected from 30 sows in an Ohio swine herd previously identified as having PEC-associated postweaning diarrhea.

IEM.

The rPEC VLPs purified from the infected Sf9 cells by CsCl gradient centrifugation were diluted 1:10 in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) and mixed with serum hyperimmune to PEC Cowden (1:500) or the dilution buffer as a control, followed by incubation at 4°C overnight (36). The mixtures were then centrifuged at 69,020 × g for 35 min. The pellets were washed once with distilled water and were then resuspended in distilled water and stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid, pH 7.0. Samples were examined using an electron microscope (Phillips 201; Philips-Norelco, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

Development of ELISA to detect PEC antibodies in swine sera. (i) Fixed-cell ELISA.

The recombinant baculovirus- and mock-infected Sf9 cells in 96-well plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, N.Y.) were fixed at PID 2 to 3 with 10% formaldehyde in 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.2) at room temperature for 30 min. The cells were then treated with 1% Triton X-100 (100 μl/well) for 2 min at room temperature. After the solution in the plates was discarded, the wells were blocked with 4% nonfat dry milk in 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.2) overnight at 4°C. After washing three times with 0.05% Tween 20–PBS (PBST), serial twofold dilutions (initial dilution of 1:25) of swine PEC antibody-positive, antibody-negative control, and test sera in PBST with 10% fetal calf serum were added to the wells. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 90 min and washed three times with PBST. Antibody binding was detected by adding 1:2,000 diluted horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-pig IgG Fc conjugate to the wells (100 μl/well) followed by incubation at 37°C for 90 min. After the plates were washed three times, the substrate, 2,2′-azino-bis-3-ethylbenz-thiazoline sulfonic acid (ABTS; Sigma) was added to the wells for color development (at 37°C for 30 min). A 0.5% SDS solution was added to each well (100 μl/well) to stop the reaction. The antibody titer was calculated as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution with an absorbance greater than or equal to the mean absorbance of antibody-negative control wells plus 3 standard deviations.

(ii) VLP ELISA.

For development of the VLP ELISA, the purified rPEC VLPs were used as antigens to coat Nunc-Immuno plates (MaxSorp surface)(Nalge Nunc International, Roskilde, Denmark) at a final concentration of 2.5 μg/ml (100 μl/well) in 0.05 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.6, and the plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were blocked with 4% nonfat dry milk in 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.2) at 37°C for 1 h and washed three times with PBST. Serial dilutions of PEC antibody-positive, antibody-negative control, and test swine sera were added, followed by sequential addition of conjugate and substrate for color development as described above. The serum antibody titers were calculated as described above.

Development of Ag ELISA to detect PEC antigens.

Pig antiserum hyperimmune to PEC Cowden was used to coat Nunc-Immuno plates (MaxSorp surface) (Nalge Nunc International) at a dilution of 1:2,000 in 0.05 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.6, and the plates were incubated at 4°C overnight, followed by blocking with 4% nonfat dry milk in 0.01 M PBS, pH 7.2. After the plates were washed three times, serial twofold dilutions (initial dilution, 1:50) of PEC-positive samples, PEC-negative control fecal samples from gnotobiotic pigs, and test samples (supernatants or cell lysates of recombinant baculovirus-infected Sf9 cell cultures) were added to the wells, followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 h. After three washes, 1:8,000-diluted guinea pig sera hyperimmune to PEC Cowden were added to the wells that were then incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Ag binding was detected by adding 1:5,000-diluted horseradish peroxidase-labeled mouse anti-guinea pig IgG conjugate (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) to the wells (100 μl/well), followed by incubation at 37°C for 60 min. The color development was as described above for the fixed-cell ELISA. The PEC Ag titer was calculated as the reciprocal of the highest sample dilution with an absorbance greater than or equal to the mean absorbance of Ag-negative control wells plus 3 standard deviations.

RESULTS

Expression of the PEC capsid proteins in baculovirus.

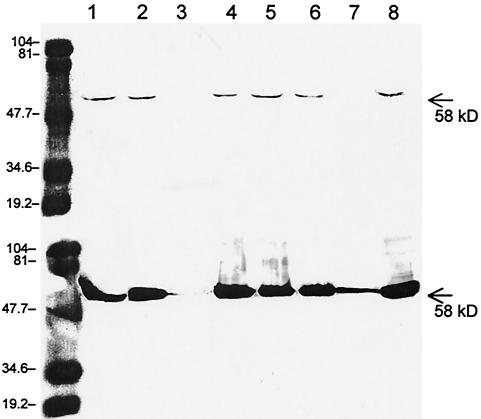

After cotransfection of Sf9 cells with linearized wild-type baculovirus DNA and the recombinant baculovirus transfer vector, pBlueTC2-6, recombinant baculoviruses were identified by plaque assay and confirmed by PCR. The plaque-purified viruses (Bac-N-BluePEC) were used to infect Sf9 cells at an ∼10 MOI for protein expression. Multiple recombinant virus clones were examined for optimal production of the rPEC VLPs. A major polypeptide band with a molecular mass of 58 kDa was identified in the cell lysates and supernatants after analysis by SDS–10% PAGE and staining with Coomassie blue. In Western blotting, this protein band was reactive only with pig serum hyperimmune against PEC Cowden but not with preexposure serum (Fig. 1). This protein band was comparatively strong in the supernatant fractions, suggesting that the recombinant capsids were released into the medium of the infected insect cells. This protein band was seen only in the recombinant virus-infected cells and not in the wild-type baculovirus- or mock-infected cells. The recombinant capsid polypeptide had the same molecular mass (58 kDa) as the native PEC capsid polypeptide, and both were recognized by convalescent-phase pig serum or pig serum hyperimmune to PEC but not by the preexposure serum in Western blotting. Interestingly, some Bac-N-BluePEC clones either did not express rPEC capsid proteins or expressed them only at very low yields (Fig. 1). We usually obtained about 5 mg of purified rPEC capsids or VLPs from 1 liter of the Sf9 cell culture, which is comparable in yield to that of VLPs from MxV (21) but much lower than that for NV (25 mg per liter) (22).

FIG. 1.

Expression of rPEC capsids detected by immunoblotting in Sf9 cells infected with each recombinant baculovirus clone. Top, supernatant; bottom, cell lysates. The far left lane shows the prestained low-range molecular weight markers. Lanes 1 to 8 were each loaded with supernatant (top) or cell lysates (bottom) from Sf9 cells infected with an individual recombinant baculovirus clone.

Dynamics of the rPEC capsid protein production in Sf9 cells.

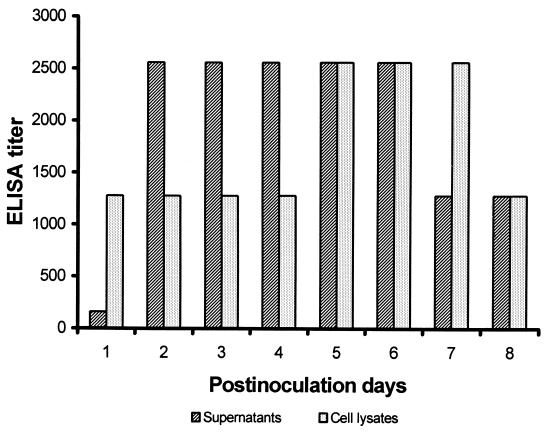

Sf9 cells infected with recombinant baculoviruses or mock-infected Sf9 cells were harvested daily from PID 1 to 8. The cell lysates and supernatants were examined either by Ag ELISA or by SDS-PAGE. Our results indicated that at PID 1 the rPEC polypeptides were produced and released into the medium at low levels by the infected Sf9 cells (Fig. 2). By PID 2, larger amounts of rPEC polypeptides were produced and released into the medium. The peak of the rPEC polypeptide expression detected in the cell lysates and supernatants was from PID 5 to 6. After PID 6, the titers of rPEC polypeptides in the supernatants decreased twofold. The optimal time for harvest of the rPEC polypeptides in the supernantants was from PID 5 to 6. SDS-PAGE analysis of the cell lysates and supernatants showed similar results. Interestingly, by PID 8 there were still large amounts of rPEC polypeptides in the cell lysates.

FIG. 2.

Dynamics of rPEC capsid production in Sf9 cells after inoculation with recombinant baculoviruses. The rPEC capsid proteins in the supernatants and cell lysates were detected by an Ag ELISA.

Self-assembly of the rPEC polypeptides into VLPs.

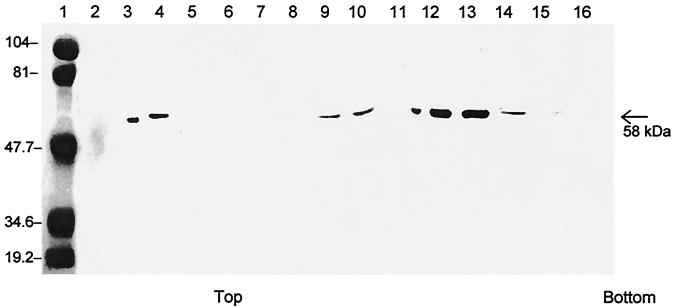

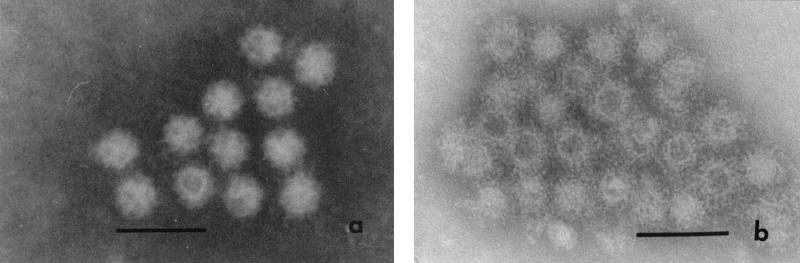

Because the rPEC capsids were released into the medium, we purified the potential VLPs from both the cell lysates and supernatants by CsCl gradient centrifugation. After CsCl gradient centrifugation, a visible band was seen in the middle of the CsCl gradients. Immunoblotting analysis of the CsCl gradient fractions indicated that the visible band contained the recombinant capsids composed of 58-kDa polypeptides which reacted with the pig serum hyperimmune to PEC (Fig. 3), confirming that the rPEC capsids were antigenically similar to the native viruses. The density of this peak fraction was 1.33 g/cm3. Furthermore, homogeneous calicivirus-like particles were observed by IEM in this fraction (Fig. 4). The VLPs were morphologically similar to the native PEC in size (average diameter, 35 to 38 nm) and possessed characteristic cup-shaped surface depressions (Fig. 4). RT-PCR was used to examine the VLP preparations, which confirmed that the VLPs didn't contain viral RNA.

FIG. 3.

CsCl gradient fractions examined by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Lanes: 1, low-range molecular weight marker; 2, Sf9 cell extract; 3, wild-type PEC; 4, tissue culture PEC; 5 to 16, CsCl gradient fractions no. 1 to 12. The density of the VLP peak fraction was ∼1.33 g/cm3.

FIG. 4.

IEM of the native PEC Cowden strain (a) and the rPEC VLP (b) incubated with hyperimmune anti-PEC serum, followed by negative staining. Bar, 100 nm.

Immunogenicity of the rPEC VLPs.

Two guinea pigs were hyperimmunized with purified rPEC VLPs and then bled 2 weeks after the last injection. The sera of both guinea pigs had high titers (102,400 and 204,800) of antibodies against rPEC capsids when tested by our ELISA. The guinea pig sera also specifically recognized the rPEC capsid proteins in Western blotting and aggregated the VLPs and the native viruses in IEM (data not shown).

Development and application of fixed-cell ELISA and VLP ELISA.

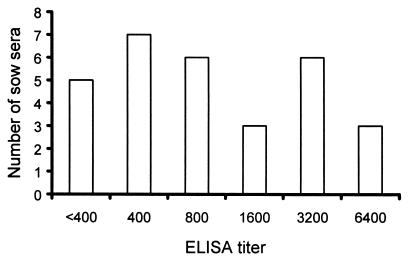

Both fixed-cell ELISA and VLP ELISA were developed and compared for detection of antibodies against PEC in swine serum samples. Among the test serum samples, all preexposure and acute-phase gnotobiotic pig sera were negative for PEC antibodies by ELISA, and all the convalescent-phase serum samples from PEC-infected gnotobiotic pigs were positive for PEC antibodies, with titers of 200 to 6,400 in both assays (partial data shown in Table 1). There was 100% agreement in the detection of PEC antibodies in gnotobiotic pig sera by the two tests (Table 1), with similar titers for each serum. The hyperimmune gnotobiotic pig antisera to porcine rotavirus and TGE coronavirus were negative for PEC antibodies by both tests. Examination of 30 sow serum samples by VLP ELISA revealed that 83.3% (25 of 30) were positive for PEC antibodies by ELISA with antibody titers ranging from 400 to 6,400 (Fig. 5). About 16.7% (5 of 30) of sows had ELISA antibody titers less than 400 that were defined as negative (Fig. 5).

TABLE 1.

Antibody titers in prechallenge (PID, 0) and convalescent-phase (PID, 28) gnotobiotic pig sera detected by fixed-cell ELISA and VLP ELISAa

| Pig no. | Antibody titers in:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Fixed-cell ELISA (convalescent phase) | VLP ELISA (convalescent phase) | |

| 1 | 3,200 | 3,200 |

| 2 | 800 | 1,600 |

| 3 | 3,200 | 6,400 |

| 4 | 1,600 | 3,200 |

| 5 | 1,600 | 800 |

| 6 | 3,200 | 3,200 |

| 7 | 3,200 | 6,400 |

| 8 | 1,600 | 6,400 |

Prechallenge antibody titers for all pigs were <1:25.

FIG. 5.

Distribution of PEC antibody titers in sow sera detected by VLP ELISA. The 30 sow sera were collected from a swine herd with PEC-associated postweaning diarrhea. Enteric caliciviruses were detected by RT-PCR in fecal samples from the normal and diarrheic postweaning pigs in the same swine herd.

DISCUSSION

A baculovirus expression system has been used to express the proteins of many DNA and RNA viruses, including NLV and SLV. It has many advantages over other expression systems: (i) high expression efficacy, (ii) eukaryotic posttranslational modifications, (iii) preservation of biological properties of recombinant proteins, and (iv) self-assembly of viral capsid proteins into VLPs for both RNA and DNA viruses (3, 5, 13, 16, 21, 22, 26, 27). The capsid proteins of NV, MxV (a Snow Mountain Agent-like virus), Lordsdale virus, Toronto virus, Hawaii virus, and RHDV were expressed efficiently in baculovirus, and the recombinant capsids self-assembled into VLPs that were antigenically and morphologically similar to their respective native viruses (5, 13, 21, 22, 26, 27). The recombinant capsids of Sapporo virus and the SLV Houston/86/US and Houston/90/US strains were also expressed in baculovirus (24, 32), but the yields of VLPs were relatively low and the VLPs tended to be unstable at pHs above 7 (32). For SLV Houston/90/US, the production of VLPs required the inclusion of an upstream sequence of the predicted capsid gene in the recombinant vector construct, but a similar construct for the Houston/86/US gave rise to no VLPs (24). In this study, the PEC capsid gene was expressed in baculovirus and the recombinant capsids of 58 kDa self-assembled into VLPs that were antigenically and morphologically similar to the native PEC Cowden. Our expression vector construct contained the T7 RNA polymerase promoter and the proposed promoter for the predicted subgenomic RNA immediately before the start codon of the putative capsid gene (14). For production of PEC VLPs, the upstream sequence of the capsid gene is not required, and it is not known if the inclusion of an upstream sequence will enhance the capsid protein expression, which was the case for SLV Houston/90/US. Instead we included a downstream sequence of 98 nucleotides at the 3′ end of the capsid gene. It would be interesting to know if the downstream sequence played some role in the expression of the rPEC capsids.

The self-assembly of rPEC capsids into VLPs and their release into the medium of infected Sf9 cells led to the simple and efficient production and subsequent purification of rPEC VLPs in large quantities. The rPEC capsid proteins were reactive with PEC antiserum and elicited high titers of serum antibodies to PEC in immunized guinea pigs. The yield of rPEC VLPs in the baculovirus expression system was similar to that for the rMxV VLPs (21), in contrast to the low yields of VLPs for Sapporo virus and the SLV Houston/90/US strain (24). The production of sera hyperimmune to PEC in guinea pigs should be conducive to the development of an Ag ELISA for detection of PEC or PEC-like viruses in fecal samples from pigs for epidemiological studies of PEC infections in swine. Our data indicated that the rPEC capsids in Sf9 cell lysates or supernatants were detected by using such an Ag ELISA. This Ag ELISA will be further evaluated for clinical diagnosis of PEC infections in swine. The rPEC VLPs which elicited high antibody titers in guinea pigs may be used as a potential future vaccine for PEC in pigs. The rNV VLPs produced in baculovirus or derived from transgenic plants were immunogenic when given orally to mice (1, 29). In a phase I trial, the rNV VLPs orally administered to volunteers were proven safe and capable of inducing immune responses in healthy adults with preexisting antibodies to NV (1). Because the HuCV are uncultivable, it is unknown if the rNV VLPs induced neutralizing antibodies in VLP-inoculated animals or human volunteers. However, the rRHDV VLPs elicited protective immunity against RHDV in inoculated rabbits and appear to be a promising candidate vaccine for rabbits. The PEC is cultivable in cell culture in the presence of intestinal content preparations from uninfected gnotobiotic pigs (34); thus we should be able to examine if the rPEC VLPs will induce serum neutralizing antibodies in pigs after inoculation.

For NV, the expression of the capsid gene in baculovirus resulted in the assembly of predominantly 38-nm VLPs but with a minority of 23-nm VLPs (40). Both VLP particles were composed of 58-kDa capsids but with different numbers of capsid units. Trypsin cleavage of the full-length capsid protein at residue 227 led to the production of a C-terminal product of 34 kDa which was detected in rNV-infected Sf9 cells by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (17, 22). After expression of SLV capsids, no smaller VLPs or similar enzyme-cleavage products were observed for PEC, Sapporo virus, and SLV Houston/90/US (24, 32).

Use of rNLV-based ELISA for detection of serum antibodies to several NLVs has led to a better understanding of the seroepidemiology of NLV infections in humans (23, 33). Because of the genetic and antigenic diversity of NLVs, ELISA tests based on only one or even several recombinant capsids may not detect infections caused by distantly related or distinct caliciviruses. For SLV infections in animals, there are currently no practical serologic tests available. In our study, the rPEC capsid proteins were expressed in large quantities inside the Sf9 cells, besides their release into the medium at PID 2, and the rPEC capsids remained in high concentration in the cell lysates until PID 7. This finding supports the applicability of our fixed-cell ELISA using recombinant baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells expressing the PEC antigens to capture serum antibodies against PEC for diagnostic serology. Our results indicated that the fixed-cell ELISA and VLP ELISA are rapid, specific, and simple and may be used for large-scale seroepidemiological investigations of PEC infections in swine. Both tests showed good agreement for detection of PEC-specific antibodies in swine sera. However, a complication was that of a higher background detected with field sow serum samples diluted less than 1:400. We are attempting to resolve this problem by adding uninfected Sf9 cell extract preparations to the serum dilution buffer. Of 30 field sow serum samples examined by VLP ELISA, 83.3% were positive for PEC antibody with antibody titers ranging from 1:400 to 1:6,400. The sow sera were collected from a swine herd with PEC-associated postweaning diarrhea identified by RT-PCR and IEM analysis of fecal samples from diarrheic pigs. Using RT-PCR, we detected Cowden-like PEC in feces from diarrheic postweaning pigs in this herd, and sequence analysis of the partial RNA polymerase region indicated that the new strains shared 89 to 92% nucleotide sequence identities with PEC Cowden (M. Guo, G. Bowman, and L. J. Saif, unpublished data). Thus the PEC infections in this swine herd were confirmed by VLP ELISA for PEC antibody detection and RT-PCR for the PEC RNA detection, confirming that PEC are circulating in the herd. In future studies using the VLP ELISA, we plan to examine additional swine serum samples from different swine herds from various locations so as to more extensively evaluate the seroprevalence of PEC infections in swine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yunjeong Kim, Peggy Lewis, Paul Nielsen, and Janet McCormick for technical assistance and acknowledge the technical support of the OARDC Molecular and Cellular Imaging Center. We are grateful to Xi Jiang (Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, Va.) and Jacqueline Noel (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.) for protocols and advice on calicivirus protein expression.

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Research Initiative, Competitive Grants Program (grant 1999 02009) and the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases (grant R01 AI 49716). Salaries and research support were provided by state and federal funds appropriated to the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, The Ohio State University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball J M, Graham D Y, Opekun A R, Estes M K. Recombinant Norwalk virus-like particles given orally to volunteers: phase I study. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:40–48. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70548-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bridger J C. Small viruses associated with gastroenteritis in animals. In: Saif L J, Theil K W, editors. Viral diarrheas of man and animals. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 161–182. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown C S, Van Lent J W M, Vlak J M, Spann W J M. Assembly of empty capsids by using baculovirus recombinants expressing human parvovirus B19 structural proteins. J Virol. 1991;65:2702–2706. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2702-2706.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dastjerdi A M, Green J, Gallimore C I, Brown D W G, Bridger J C. The bovine Newbury agent-2 is genetically more closely related to human SRSVs than to animal caliciviruses. Virology. 1999;254:1–5. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dingle K E, Lambdem P R, Caul E O, Clarke I N. Human enteric Caliciviridae: the complete genome sequence and expression of virus-like particles from a genetic group II small round structured virus. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2349–2358. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-9-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estes M K, Atmar R L, Hardy M E. Norwalk and related diarrhea viruses. In: Richman D D, Whitley R J, Hayden F G, editors. Clinical virology. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 1073–1095. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fankhauser R L, Noel J S, Monroe S S, Ando T, Glass R I. Molecular epidemiology of “Norwalk-like viruses” in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1571–1578. doi: 10.1086/314525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flynn W T, Saif L J. Serial propagation of porcine enteric calicivirus-like virus in porcine kidney cells. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:206–212. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.2.206-212.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn W T, Saif L J, Moorhead P G. Pathogenesis of porcine enteric calicivirus in four-day-old gnotobiotic piglets. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:819–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glass P J, White L J, Ball J M, Lepare-Goffart I, Hardy M E, Estes M K. Norwalk virus open reading frame 3 encodes a minor structural protein. J Virol. 2000;74:6581–6591. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6581-6591.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green K Y, Ando T, Balayan M S, Berke T, Clarke I N, Estes M K, Matson D O, Nakata S, Neill J D, Studdert M J, Thiel H-J. Taxonomy of the caliciviruses. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl. 2):S322–S330. doi: 10.1086/315591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green K Y, Lew J F, Jiang X, Kapikian A Z, Estes M K. A comparison of the reactivities of baculovirus-expressed recombinant Norwalk virus capsid antigen with the native Norwalk virus in serologic assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2185–2191. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2185-2191.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green K Y, Kapikian A Z, Valdesuso J, Sosnovetsev S, Treanor J J, Lew J F. Expression and self-assembly of recombinant capsid protein from the antigenically distinct Hawaii human calicivirus. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1909–1911. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1909-1914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo M, Chang K-O, Hardy M E, Zhang Q, Parwani A V, Saif L J. Molecular characterization of a porcine enteric calicivirus genetically related to Sapporo-like human caliciviruses. J Virol. 1999;73:9625–9631. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9625-9631.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo M, Evermann J F, Saif L J. Detection and molecular characterization of cultivable caliciviruses from clinically normal mink and enteric caliciviruses associated with diarrhea in mink. Arch Virol, 2001;146:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s007050170157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hale A D, Crawford S E, Ciarlet M, Green J, Gallimore C, Brown D W, Jiang X, Estes M K. Expression and self-assembly of Grimsby virus: antigenic distinction from Norwalk and Mexico viruses. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:142–145. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.1.142-145.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy M E, White L J, Ball J M, Estes M K. Specific proteolytic cleavage of recombinant Norwalk virus capsid protein. J Virol. 1995;69:1693–1698. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1693-1698.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang X, Cubitt D W, Berke T, Dai X M, Zhong W M, Pickering L K, Matson D O. Sapporo-like human caliciviruses are genetically and antigenically diverse. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1813–1827. doi: 10.1007/s007050050199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang X, Cubitt D W, Hu J, Treanor J J, Dai X, Matson D O, Pickering L K. Development of a type-specific EIA for detection of Snow Mountain agent-like human caliciviruses in stool specimens. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2739–2747. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-11-2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang X, Matson D O, Cubitt W D, Estes M K. Genetic and antigenic diversity of human caliciviruses (HuCVs) using RT-PCR and new EIAs. Arch Virol. 1996;12:S251–S262. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang X, Matson D O, Ruiz-Palacios G M, Hu J, Treanor J J, Pickering L K. Expression, self-assembly and antigenicity of a Snow Mountain-like calicivirus capsid protein. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1452–1455. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1452-1455.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang X, Wang M, Graham D Y, Estes M K. Expression, self-assembly, and antigenicity of the Norwalk virus capsid protein. J Virol. 1992;66:6527–6532. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6527-6532.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang X, Wilton N, Zhong W M, Berke T, Huang P W, Barret E, Guerrero M, Ruiz-Palacios G M, Green K Y, Hale A D, Estes M K, Pickering L K, Matson D O. Diagnosis of human caliciviruses by use of enzyme immunoassays. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl 2):S349–S359. doi: 10.1086/315577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang X, Zhong W M, Kaplan M, Pickering L K, Matson D O. Expression and characterization of Sapporo-like human calicivirus capsid proteins in baculovirus. J Virol Methods. 1999;78:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapikian A Z, Estes M K, Chanock R M. Norwalk group of viruses. In: Fields B N, et al., editors. Virology. Philadephia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 783–810. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurent S, Vautherot J F, Madelaine M F, Le Gall G, Rasschaert D. Recombinant rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus capsid protein expressed in baculovirus self-assembles into virus-like particles and induces protection. J Virol. 1994;68:6794–6798. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6794-6798.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leite J P, Ando T, Noel J S, Jiang B, Humphrey C D, Lew J F, Green K Y, Glass R I, Monroe S S. Characterization of Toronto virus capsid protein expressed baculovirus. Arch Virol. 1996;141:865–875. doi: 10.1007/BF01718161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu B L, Lambden P R, Günther H, Otto P, Elschner M, Clarke I N. Molecular characterization of a bovine enteric calicivirus: relationship to the Norwalk-like viruses. J Virol. 1999;73:819–825. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.819-825.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mason H S, Ball J M, Shi J, Jiang X, Estes M K, Arntzen C J. Expression of Norwalk virus capsid protein in transgenic tobacco and potato and its oral immunogenicity in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5335–5340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mead P S, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig L F, Bresee J S, Shapiro C, Griffin P M, Tauxe R V. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:607–625. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noel J S, Liu B L, Humphrey C D, Rodriguez E M, Lambden P R, Clarke I N, Dwyer D M, Ando T, Glass R I, Monroe S S. Parkville virus: a novel genetic variant of human calicivirus in the Sapporo virus clade, associated with an outbreak of gastroenteritis in adults. J Med Virol. 1997;52:173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Numata K, Hardy M E, Nakata S, Chiba S, Estes M K. Molecular characterization of morphologically typical human calicivirus Sapporo. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1537–1552. doi: 10.1007/s007050050178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker S P, Cubitt W D, Jiang X. The application of an enzyme immunoassay using a baculovirus expressed recombinant human calicivirus (Mexico virus) for the study of outbreaks of gastroenteritis and determining its sero-prevalence in children in London, UK. J Med Virol. 1995;46:194–200. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890460305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parwani A V, Flynn W T, Gadfield K L, Saif L J. Serial propagation of porcine enteric calicivirus: effects of medium supplementation with intestinal contents or enzymes. Arch Virol. 1991;120:115–122. doi: 10.1007/BF01310954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prasad B V V, Rothnagel R, Jiang X, Estes M K. Three-dimensional structure of baculovirus-expressed Norwalk virus capsids. J Virol. 1994;68:5117–5125. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5117-5125.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saif L J, Bohl E H, Theil K W, Cross R F, House J A. Rotavirus-like, calicivirus-like, and 23 nm virus-like particles associated with diarrhea in young pigs. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;12:105–111. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.1.105-111.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vinje J, Altena S A, Koopmans M P G. The incidence and genetic variability of small round-structured viruses in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the Netherlands. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1374–1378. doi: 10.1086/517325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vinje J, Deijl H, van der Heide R, Lewis D, Hedlund K-O, Svensson L, Koopmans M P G. Molecular detection and epidemiology of Sapporo-like viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:530–536. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.530-536.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White L J, Ball J M, Hardy M E, Tanaka T N, Kitamoto N, Estes M K. Attachment and entry of recombinant Norwalk virus capsids to cultured human and animal cell lines. J Virol. 1996;70:6589–6597. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6589-6597.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White L J, Hardy M E, Estes M K. Biochemical characterization of a small form of recombinant Norwalk virus capsids assembled in insect cells. J Virol. 1997;71:8066–8072. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.8066-8072.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wirblich C, Theil H-J, Meyers G. Genetic map of the calicivirus hemorrhagic disease virus as deduced from in vitro translation studies. J Virol. 1996;70:7974–7983. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7974-7983.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]