Abstract

Background

Committed to implementing a person-centered, holistic (Whole Health) system of care, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) developed a peer-led, group-based, multi-session “Taking Charge of My Life and Health” (TCMLH) program wherein Veterans reflect on values, set health and well-being-related goals, and provide mutual support. Prior work has demonstrated the positive impact of these groups. After face-to-face TCMLH groups were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, VHA facilities rapidly implemented virtual (video-based) TCMLH groups.

Objective

We sought to understand staff perspectives on the feasibility, challenges, and advantages of conducting TCMLH groups virtually.

Methods

We completed semi-structured telephone interviews with 35 staff members involved in the implementation of virtual TCMLH groups across 12 VHA facilities and conducted rapid qualitative analysis of the interview transcripts.

Results

Holding TCMLH groups virtually was viewed as feasible. Factors that promoted the implementation included use of standardized technology platforms amenable to delivery of group-based curriculum, availability of technical support, and adjustments in facilitator delivery style. The key drawbacks of the virtual format included difficulty maintaining engagement and barriers to relationship-building among participants. The perceived advantages of the virtual format included the positive influence of being in the home environment on Veterans’ reflection, motivation, and self-disclosure, the greater convenience and accessibility of the virtual format, and the virtual group’s role as an antidote to isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Faced with the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, VHA pivoted by rapidly implementing virtual TCMLH groups. Staff members involved in implementation noted that delivering TCMLH virtually was feasible and highlighted both challenges and advantages of the virtual format. A virtual group-based program in which participants set and pursue personally meaningful goals related to health and well-being in a supportive environment of their peers is a promising innovation that can be replicated in other health systems.

Keywords: health coaching, implementation and dissemination, telemedicine, support group, veterans, qualitative

Background

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is one of the largest integrated health care systems in the United States and has long been on the forefront of transforming health care delivery to a patient-centered, holistic model focused on what matters most to each individual Veteran. Accordingly, in 2011, VHA tasked the newly established Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT) with spearheading this profound shift in the culture of health care delivery across the entire VHA system of care. 1 VHA has since been striving to create a Whole Health system of care in which Veterans are empowered to collaborate with their care team as equal partners and pursue personally meaningful goals related to their health and well-being. 2

Taking Charge of My Life and Health (TCMLH) is part of what VHA calls the “Pathway,” or the entry point to Whole Health. A group-based program, TCMLH is designed to help Veterans start reflecting on what really matters to them, set preliminary goals, and take first steps toward becoming empowered and engaged in their health and well-being. As an alternative to TCMLH, Veterans may also choose to work one-on-one with a peer. TCMLH is ideally facilitated by 1–2 fellow Veterans (known as Whole Health partners), but Veterans in other roles (eg, health coaches) and non-Veterans can facilitate, as well. While TCMLH can encompass as many as 6-9 sessions, some VHA facilities choose to adopt a shorter curriculum (1–2 or 4 sessions).

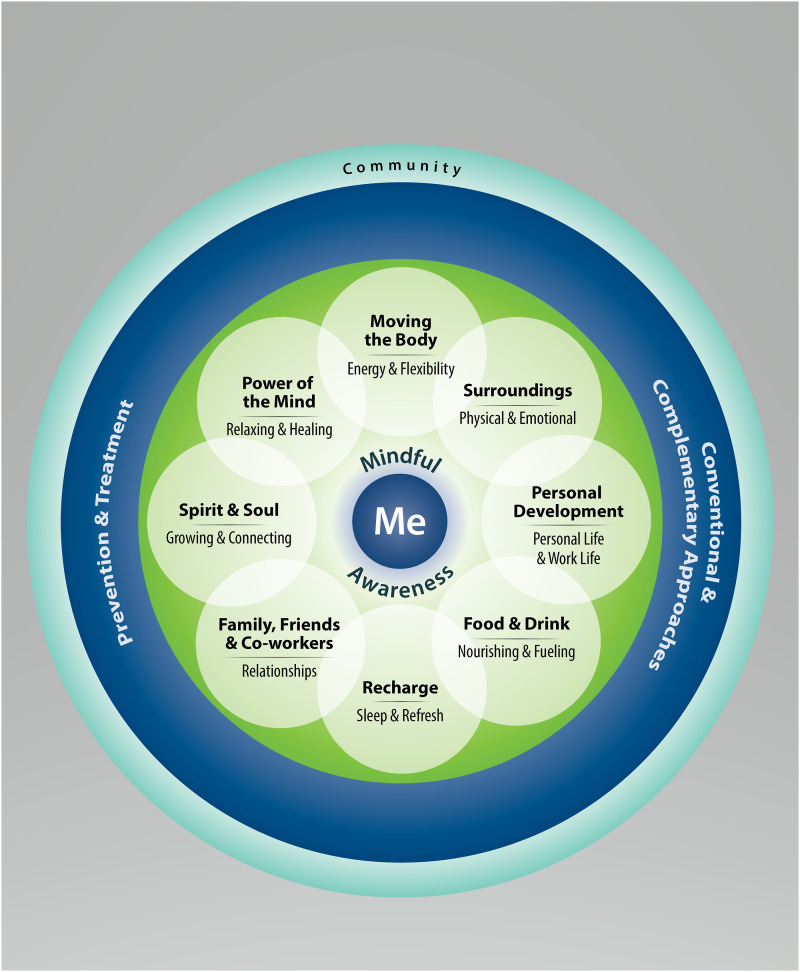

Regardless of the logistics, the TCMLH curriculum remains consistent. In the initial session(s), Veterans reflect on what really matters to them (also known as their “mission, aspiration, and purpose”) and evaluate their current experience in eight areas, known as Core Components of Health and Well-Being (Figure 1). These Core Components encompass multi-faceted aspects of well-being and include topics that cover physical wellness (ie, working the body, food and drink) and psychosocial wellness (ie, interpersonal relationships, spirit and soul). 3 The emphasis on reflection is maintained throughout the initial TCMLH session through repeated incorporation of mindful awareness activities. In the subsequent sessions, facilitators share information pertinent to each of the eight areas, for example, self-care ideas, and encourage additional discussion among the participants. While facilitators generally abstain from providing direct advice, they guide participants in setting and pursuing SMART (specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic, and timed) goals 4 that resonate with what really matters to each participant. Veterans may choose to share their goals with the rest of the group and/or ask for support and ideas on navigating barriers to goal attainment.

Figure 1.

The circle of health.

Typically, the last 1–2 TCMLH sessions allocate time for Veterans to reflect on their progress and put together a personal health plan (PHP). The culmination of the work completed throughout the series, the PHP details what matters most to the Veteran and outlines health and well-being goals to pursue with support from the Veteran’s clinical care team and/or Whole Health programs offered across VHA. Ideally, the PHP is a living document accessible to the Veteran’s entire clinical team through the electronic health record. Veterans are also encouraged to keep a wallet card with a briefer version of the PHP with them and share it with their providers at subsequent appointments.

Literature, including prior studies by this team, suggests that participating in TCMLH positively impacts outcomes among Veterans. A single-site pilot evaluation that administered a survey to Veterans before and after participating in a 9-week TCMLH program discovered a significant decrease in perceived stress and significant improvements in self-reported mental health and quality of life, sense of meaning in life, and patient engagement in health care. 5 A subsequent evaluation examined outcomes for a larger sample of Veterans across multiple VHA facilities immediately after and 2 months following TCMLH participation. 6 Significant gains were observed in participant self-reported mental health, perceived stress, self-care attitudes and behaviors, patient motivation, sense of meaning and purpose, goal progress, and goal-specific hope immediately after TCMLH participation. Further, this work found that improvements in patient motivation, perceived stress, goal-specific hope, and goal progress were maintained 2 months after participation.

Until the Spring of 2020, TCMLH was typically offered in-person, although a small number of VHA facilities had started exploring virtual formats. However, when VHA, like other health care systems, had to shift its operations in response to the threat of the COVID-19 pandemic,7,8,9 TCMLH was also affected. Many facilities had to discontinue face-to-face TCMLH groups and rapidly pivot to a virtual format. This rapid implementation of virtually delivered TCMLH, which took place under unprecedented circumstances, presented facilities with a slew of challenges and opportunities. In this paper, we offer insights on the feasibility, challenges, and advantages of offering this evidence-based Whole Health group virtually.

Methods

We conducted and analyzed semi-structured qualitative interviews with staff members involved in running TCMLH groups at 12 VHA facilities. These interviews were conducted between the Summer of 2020 and the Spring of 2021 as part of a larger, ongoing mixed-methods program evaluation of TCMLH. Of note, the evaluation of TCMLH is a component of a larger multi-year, multi-component evaluation of the VHA Whole Health System of Care (EPCC).2,10,11 Interviews with staff members were scheduled to begin in Spring 2020. However, we made a decision to delay the interviews until Summer 2020 so as to give sites more time to adjust to providing TCMLH in a virtual format and, therefore, gain more experience to draw on for the interview. This project was classified as non-research/quality improvement by the VA Bedford Institutional Review Board, as the primary goal was to inform VA leadership about sites’ experiences with providing TCMLH virtually.

Setting

We strove to include a diverse range of sites (see Table 1) to ensure breadth of representation in terms of geographical location, organizational complexity, and degree of involvement in the Whole Health initiatives (eg, sites with both a robust pre-existing Whole Health infrastructure and those relatively new to the Whole Health initiative).

Table 1.

Site Characteristics.

| Site | Location | Complexity a | WH Designation b | Number of Interviewees per Site [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Northeast | High | Flagship Site | 5 (14.3%) |

| 02 | Northeast | Low | Learning Collaborative 2 | 1 (2.9%) |

| 03 | Northeast | Medium | None | 1 (2.9%) |

| 04 | Mid-Atlantic | High | Design Site | 5 (14.3%) |

| 05 | Mid-Atlantic | High | Flagship Site | 3 (8.5%) |

| 06 | South | High | Flagship Site | 1 (2.9%) |

| 07 | Mid-West | High | None | 2 (5.7%) |

| 08 | Mid-West | High | Design Site | 3 (8.5%) |

| 09 | Mid-West | High | Flagship Site | 2 (5.7%) |

| 10 | South | High | Flagship Site | 5 (14.3%) |

| 11 | West | High | Flagship Site | 2 (5.7%) |

| 12 | Mid-West | High | Flagship Site | 5 (14.3%) |

| Total | 35 (100%) | |||

aVHA assigns each of its facilities to a complexity level (low, medium or high) based on the levels of patient volume and complexity, patient risk, teaching and/or research activity, the number of physician specialists, and the level of ICU units on site.

bWhole Health Flagships are sites that are receiving the highest volume of support (funding, education, implementation assistance) for Whole Health system implementation and are expected to implement all components of the Whole Health system, whereas Design sites are tasked with implementing specific components of the Whole Health system. The first 18 Flagships and 18 Design sites were designated in 2018. Since then, some of the Design sites have been moved into the Flagship category and additional sites have received a Flagship or Design designation. In 2019, each VISN (Veterans Integrated Service Network) selected two additional sites to participate in the new wave of Whole Health implementation as members of the Whole Health Learning Collaborative 2. While some VA sites do not have a special designation yet, it is expected that eventually all VA facilities will implement the Whole Health system fully.

Participants and Recruitment

Two authors (A.B. and A.H.), with assistance from OPCC&CT, worked to identify sites and prospective participants. We continued to approach sites until we had a sufficient number of facilities to ensure variation in organizational characteristics and level of overall Whole Health implementation, as noted above. At the 12 participating sites, we strove to recruit individuals who were involved in facilitating TCMLH groups at their sites (Whole Health partners and/or health coaches), as well as staff members in a supervisory capacity who generally had a broader Whole Health program support role at their site, with TCMLH being one aspect of their responsibilities (program managers). We approached prospective participants via email, providing a short description of the evaluation and inviting them to participate in an interview. We provided information sheets that included all of the information typically detailed in informed consent forms (eg, voluntary nature of participation, confidentiality considerations) at initial outreach. Prior to each interview, we obtained verbal assent from each participant.

Data Collection

Interviews took place between July 2020 and March 2021 by phone or over videoconferencing software, depending on the interviewee’s preference. Both interviewers (E.A. and K.D.) were experienced qualitative health services researchers with expertise in cultural anthropology and psychology, respectively. The interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide that was developed by the interviewers iteratively, with input from the other team members, including a Veteran consultant (R.P.K.). The interview guide included questions about the site’s approach to and experiences with TCMLH prior to and after the switch to a virtual format, with a particular focus on perceived challenges and benefits of virtually delivered TCMLH. Interview guides for program managers and facilitators were slightly different, with the former focusing predominantly on the overall logistics and the “big picture” and the latter exploring facilitators’ first-hand experiences (see Supplementary Appendices 1 and 2). As some of the interviewees had prior experience with in-person TCMLH while others, mainly those hired after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, did not, the flow and content of the interview was slightly different for these two categories of participants. In two cases, due to our interviewees’ preference, we paired the sites’ facilitators and program managers for the interview. All interviews were audio-recorded with the interviewees’ permission. The length of the interviews ranged from 27 min to 85 min (median—60 minutes).

Data Analysis

Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription agency. We used a modified form of rapid qualitative analysis developed by Hamilton and colleagues.12,13 First, two authors (E.A. and K.D.) created a summary template organized by interview topics (eg, “tele-TCMLH challenges,” “recruitment challenges”). These two authors then independently summarized the same three transcripts using the template and discussed experiences, which resulted in several sections in the template being merged or added anew. After the template was finalized, three authors (E.A., K.D., Z.R.) applied the summary template to the remaining transcripts. In a departure from Hamilton’s approach, we also included illustrative quotes at the bottom of each template, numbering them and referencing them in the main text of the summary (Q1, Q2, etc.) for ease of retrieval. As a final preparatory step, contents of each summary (with the exception of the illustrative quotes) were extracted and pasted into a Microsoft Excel matrix, with rows corresponding to participants and columns corresponding to template domains. After the matrix was constructed, the same three analysts reviewed the matrix to identify recurring themes. To fully develop each theme, the analysts reviewed the quotations captured in the templates and purposefully looked for variation and counterexamples across participants. The themes were further refined with input from the larger group of authors.

Results

We interviewed a total of 35 participants, including 22 TCMLH facilitators and 13 program managers. For each site, we interviewed between 1 and 5 staff members (see Table 1). Aggregate data about participants is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interviewee Characteristics.

| Characteristics | No. Interviewees [n (%)] | |

|---|---|---|

| Interviewees by TCMLH Role (N = 35) | Facilitators a | 22 (62.8%) |

| Program directors/managers/supervisors b | 12 (34.3%) | |

| Dual role c | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Interviewees by years in VA (N = 35) | <1 year | 3 (8.6%) |

| 1–2 years | 10 (28.6%) | |

| 3–5 years | 4 (11.4%) | |

| 6–10 years | 4 (11.4%) | |

| 10+ years | 6 (17.1%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (22.9%) | |

| Interviewees by veteran status (N = 35) | Veteran | 18 (51.4%) |

| Non-veteran | 8 (22.9%) | |

| Unknown | 9 (25.7%) | |

aIncludes Whole Health Partners, Whole Health Coaches, Peer Support Specialists, Clinicians.

bIncludes Whole Health Clinical Directors, Whole Health (or aligned service) Program Managers, Coach/Partner Supervisors.

cBoth facilitator and supervisory roles.

In their interviews, participants pointed to both challenges and advantages of TCMLH groups delivered virtually. These experiences are described below with select illustrative quotes. For each quote, participant ID (01-35) and their site ID (01-12) are provided. For additional representative quotes, see Supplementary Appendix 3.

Challenges of Virtual TCMLH

Navigating the Logistics

Before the pandemic, most of the sites included in this study offered TCMLH exclusively in-person. The shift away from face-to-face encounters to telemedicine in Spring 2020 was abrupt, posing logistical challenges for all of the facilities represented in our evaluation.

Recruitment

In a remarkably short time frame, facilities had to set up a new scheduling system and adjust their recruitment approach to the new reality that made some of the older approaches, for example, relying on passive advertisement using flyers, less effective. As one participant put it:

“…I think, promotion really is the hardest thing, getting the word out there. We have fewer veterans coming to the VA, in general. So, if we put out flyers, or if we do in-reach, we’re targeting and reaching a smaller, smaller pool of people than we would if we were open 100 percent” (Participant_34_Site_12).

All sites continued to rely on promoting TCMLH during the “Orientation to Whole Health” session (a standalone introduction to Whole Health that is open to all Veterans and staff members and that is supposed to be offered regularly at all VAs). This strategy was extraordinarily successful at one site:

“I think we have really good facilitators… in terms of orientation. I think we sell it really well… we really pride ourselves on Whole Health…we participate in it ourselves, we practice it… we’re constantly, you know, assessing ourselves and wanting to be better and wanting to, I guess, lead by example… We promote all of our offerings and all of our modalities and TCMLH is just one that is at the top of the list” (Participant_20_Site_06).

However, relying on Orientation was not a panacea as its success depended on the staff’s ability to compellingly explain the nature and value of TCMLH to Veterans who had just been introduced to the basics of Whole Health. Furthermore, because the Orientation itself transitioned to the virtual format and staff were no longer able to rely on hardcopy sign-up sheets, time-intensive follow-up was then required to ensure that Veterans from the Orientation remembered to sign up for TCMLH and, perhaps more importantly, still had the motivation to do so.

Facilities also continued to draw on referrals from clinicians (oftentimes primary care and mental health care providers) as their recruitment pool for TCMLH, but the success was more likely at those VAs that had already developed a robust process for encouraging clinicians to refer Veterans to TCMLH, as well as for following up on the received referrals. This was conveyed in a group interview at one of such successful sites:

“…what we know is that… this is such a collective network of effort. Our schedulers are super-critical to this process. We cannot be successful without good schedulers… So the scheduler’s not even in the group but they hold a critical piece to connecting us all” (Participants_29_30_Site_09).

Similarly, some facilities implemented outreach to the Veterans who had previously signed up to receive Whole Health programming updates, participated in other well-being services and/or completed several sessions of TCMLH in person but subsequently dropped out. These approaches were successful at several facilities, but this was, once again, contingent on the already-existing infrastructure for keeping track of Veterans interested in Whole Health and/or previously enrolled in TCMLH, as well as on the staff’s ability to promote TCMLH during outreach.

Technology

Another logistical challenge faced by facilities was deciding which platform to use for virtual delivery of TCMLH groups. While some experimented with WebEx and even telephone, most eventually converged on the VHA application, VA Video Connect (VVC), that was developed specifically for VHA telehealth appointments (ie, video visits). VVC includes group call functionality, which provided a reasonable solution to the challenge of pivoting to the virtual format, yet most interviewees also commented on the disruptive effects of audio quality, time lag, and accidental unmuting:

“Really, the most challenging aspect is just the technology. You know, the VA Video Connect … is very easy to navigate but the technology itself is, you know, inconsistent. So, sometimes Veterans will connect but they’ll have a poor connection, or their connection will freeze, and they’ll get disconnected. So, they have to reconnect and that can disrupt the conversation and facilitation of group” (Participant_22_Site_07).

Furthermore, interviewees often commented on the unique technological challenges that both facilitators and Veteran participants may face. There was a sense that older Veterans, in particular, may be less comfortable with technology or have insufficient access to it:

“The biggest challenge is the older Veterans because they’re not computer savvy like us younger guys are, and… they struggle getting online and … talking with us, and… you know, whenever they have problems, I really want to just run over there and run to their computer and say, ‘Okay, I got it fixed, we’re good; so, I’ll see you later.’ But… I can’t do that because they’re on the other side of the screen” (Participant_32_Site_11).

As the time went on, however, we started hearing that the situation had improved. Several sites reported success with putting one of the co-facilitators in charge of technological issues, allowing one facilitator to continue with the session, while the other would deal with the problem. Local support, either from tech-savvy members of the Whole Health team itself or from the site’s IT department, was also invaluable in helping facilitators and Veterans alike navigate technology-related issues. Furthermore, VHA’s broader initiatives to distribute iPads to the Veterans lacking access to mobile/computing devices and to make improvements to the VVC interface (eg, increasing the number of participants visible on the screen at the same time, increasing the platform’s bandwidth) also played a positive role. Indeed, many interviewees also observed that Veterans, some of whom were participating in several virtual groups at once, quickly gained a great deal of aptitude with VVC, as mentioned by one interviewee:

“I think… some of the initial barriers of being uncomfortable with the technology and the physical nuances of being at home… were quickly eliminated and the access and usability really flourished…” (Participant_31_Site_10).

Difficulty Maintaining Engagement

TCMLH as a program seeks to stimulate reflection and promote self-driven behavior change among participants. Therefore, it is not surprising that the majority of participants highlighted the challenges of maintaining engagement as a key drawback of the virtual format. As an extreme example, one interviewee recalled that a TCMLH participant fell asleep during a virtual meditation activity and did not wake up even when the group moved on, forcing the group facilitators to mute them. Some attributed the engagement challenges to the inherently limited functionality of VVC for group-based, interactive, and multimedia-based activities:

“I think [it’s] important to remember that VVC… was designed for the medical model and a one-on-one doctor’s appointment. So, part of what we struggle with… is that the software is not designed for flexibility, creativity, you know, using videos, using breakout rooms. These are all things that this software does not allow us to do so sometimes being engaging is more challenging in this format…” (Participants_29_30_Site_9)

Others stated that it was difficult to pick up on participants’ “energy” or non-verbal cues, framing this as a barrier to engagement. As one interviewee put it:

“I think connecting electronically is different than connecting face-to-face, and… while there are many benefits to being able to connect virtually, I think especially when it’s a group that meets regularly and it’s connected in that way… the face-to-face connections, and being able to read body languages, and especially… being able to sort of adjust to meet the Veterans based on their body language and response to what you’re providing is probably a little bit easier face-to-face than virtual” (Participant_08_Site_04).

Interestingly, in juxtaposition, a minority of participants did feel that the virtual format was more conducive toward the reading of non-verbal cues, due to the visual layout (being able to catch a quick glimpse of everyone’s face at the same time):

“…when you’re in a class and somebody’s speaking, your attention is on the person speaking. So, you may miss… some key visual clues from somebody sitting… next to you or sitting down the table. The… telehealth format with everybody’s face right in front of me, it’s very easy to, when somebody’s speaking, to scan everybody to see how they’re reacting to what’s being said. To see how they’re… absorbing … the concepts for that day. It makes it very easy to come back and go, ‘I… noticed that you seemed to have a question face?’” (Participant_26_Site_09).

In response to the engagement challenges, several facilitators described consciously modifying their own facilitation style by being more energetic and/or using engaging activities, such as movement breaks. As one interviewee put it:

“Well, I kinda tell ‘em up front that, you know… ‘you gotta make me look good. You gotta come back. <…> I need for you to come back.’ …I try to make it as fun as I can and go with some jokes and… tease ‘em about things that I know” (Participant_14_Site_05).

Obstacles to Relationship-Building

As a peer-led, group-based program, TCMLH puts a strong emphasis on Veterans bonding and holding one another accountable. However, numerous interviewees felt that the virtual format impeded relationship-building among participants. Many interviewees noted that Veterans did not feel part of a group to the same extent as when TCMLH was offered in-person. One program manager explicitly connected this to the physical limitations of virtual TCMLH:

“When we were doing that in person… the dynamics of the room, with the way the room is structured… you could physically get up and go and talk to somebody... You can… have eye contact. You can have somewhat physical contact. I think we got better buy-in when we did it that way as opposed to doing it by… VVC just because you’re kind of isolated and you’re kind of not there and you don’t get the personalization that you get when you’re in a room together with other people” (Participant_27_Site_09).

Numerous staff members also observed that participants were no longer exchanging their contact information or forming relationships that would extend outside of the confines of the group, as they had when the program was offered in-person:

“[Interviewer: do you see other ways in which people are connecting even though it’s a virtual group?] I can’t say that I do, no. …I mean… when I was doing it face-to-face, they would exchange numbers, and they would form relationships. I haven’t seen that done virtually” (Participant_24_Site_08).

Several interviewees specifically attributed this lack of connection outside of the group to the inability of participants to have informal interactions during breaks or after each group section, for example, going out for coffee or to have lunch together:

“I think most of them—you know, when they click off, they click off. They don’t call each other up and have a conversation, but when they’re leaving group, and they had something to discuss, you know, they walk down the hall together, they talk to somebody, they go to the cafeteria and eat lunch together, they… connect with somebody on their phone, not me saying, ‘Hey, why don’t you call this guy?’” (Participant_25_Site_08).

In one notable counterexample, however, one facilitator opined that the virtual format was not an obstacle to connection and that Veterans taking part in virtual TCMLH were more eager to stay in touch than face-to-face group participants:

“It’s still an opportunity to connect with others, even though you’re not in each other’s space. You still have the opportunity to see them, to hear them. You can feel them; you know, you still can get emotions from seeing them through the camera. I mean, you still make those connections. <…> So, I’ve experienced that they exchange contact information in the chat box—phone numbers, emails, and they create a support group. So, you know, versus if they’re face-to-face… you may see one or two people exchange numbers, but virtually, once one person puts their information on it, everybody just starts putting information on there” (Participant_12_Site_04).

Furthermore, several interviewees shared that, in their opinion, it was possible for Veterans to form personal relationships with other participants of virtually delivered TCMLH groups, although this did take longer in the virtual format. One facilitator thought that at least some continuity among attendees was key to the groups “gelling” together:

“…when we used to do open face-to-face groups … they did have an opportunity to gel and then support each other and become that community for each other. Now, that might not necessarily work for on-line open group because you never really know if you’re going to have the same group of people... I’ve noticed that… even if you just have two groups that have the same people, by the end of that second group, they end up sharing each other’s contact information and becoming something other than just attendees in a group” (Participant_18_Site_06).

Benefits of Virtual TCMLH

Home Environment as a Source of Insight and Motivation

As mentioned in the introduction, a central component of TCMLH groups is to allow Veterans to reflect on what is important to them and help them set and stick to realistic, personally meaningful goals. Several staff members we interviewed observed that participating from home may stimulate reflection and strengthen a sense of motivation in Veterans. One facilitator thought that Veterans may find it easier to reflect on what really matters to them when surrounded by personally relevant cues, such as photos or memorabilia:

“…maybe they’ll grab a photo and you know, ‘This is me, this is what I wanna go back to. This is why I wanna spend some time on working the body and understand what that means for me because I wanna get back to this guy.’ You know, or having those pictures of family members right there when we’re talking about family, friends and coworkers might bring something out that I can help them with...” (Participant_35_Site_12).

Similarly, another TCMLH facilitator suggested that participating from their home environment may help Veterans set more concrete goals:

“…it really helps when we’re talking about what the values are or what their action steps will be achieving their goals, because they’re in their environment. They’re immediately able to think about, ‘Okay, so, you know, I plan to move my body and one of my actions is to, you know, see how far I can run around the block just to get a sense of where I’m at.’ I’m able to visualize and to gesture during the session about their route. … They’re in vivo. They’re able to refer to their life real time rather than coming to a group and sort of, you know, imagining what it would be like” (Participant_22_Site_07).

Interestingly, one interviewee also mentioned that observing Veterans in their home environment is beneficial for the TCMLH facilitators as a source of deeper insight into the Veterans’ lives, including barriers or support needs they may be dealing with:

“It’s giving me a different peek into their life that showing up at the campus didn’t necessarily give me, you know. … So, it… frames… my thinking about how I can support this Veteran. If I’m noticing clutter and things like that, you know, I’ll have a one-on-one conversation with the Veteran later <because> I know now how to frame some questions about how things are going in his personal life” (Participant_03_Site_01).

Improved Comfort With Sharing

Although TCMLH participants are not required to share their thoughts in detail if they do not want to, self-disclosure is a beneficial aspect to TCMLH participation. By speaking up, Veterans get a chance to engage in active self-reflection and to benefit from the perspective and support of other participants and/or the TCMLH facilitator(s). Several interviewees thought that participating from the comfort of their homes made Veterans more comfortable and more likely to share their thoughts and experiences with others. Different explanations were offered for this phenomenon. One staff member remarked that the physical distance afforded by telehealth may make it easier for some participants to open up:

“People seem to be more open to talking. It’s almost like the physical distance gives them a little bit more security about being able to really dive deeper into themselves. And then to share their thoughts. …I’ve had individuals in class, you know, tell us something … <like,> ‘…I don’t know why I’m telling you this now, cause I haven’t told anybody in my life about this.’ … I’ve never heard that face-to-face. Ever. But I’ve heard it a couple of times in… telehealth world” (Participant_26_Site_09).

Another participant suggested that being in a public space is associated with distinct behavioral expectations and is inherently less relaxing than being at home; for some Veterans, this interviewee suggested, participating from home helps lower their guard:

“. . . it allows people to be more expressive because they’re in the comfort of their own home or their office. Like, they’re in their space… ‘Cause you know when you go somewhere—if you go to church, you dress up; if you go to the grocery store, you don’t… So, when you’re at home, you’re more relaxed, and you’re in your own favorite chair. And, so, now… you’re not so defensive. Because some … Veterans have been deployed, and they have combat PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]… you know, they’re on the defense. So, if I’m at home, I’m not thinking about who’s coming in. I’m not thinking about, you know, who opens the door. I’m just like, ‘…now that I’m home, I’m not worried about protecting myself; so, I can just talk, I can just let it out’” (Participant_08_Site_04).

Yet another facilitator, drawing on their own experience as a Veteran, hypothesized that there may be something especially uncomfortable about visiting a VA hospital due to its association with the emotionally reserved military culture, and suggested that participating from home removes this uneasy emotional valence:

“…a lot of the times, when they come to the hospital, especially a VA hospital… you don’t wanna say anything out of the way just because that’s a lot of the culture in the military is ‘don’t say anything or you’ll lose your career’… So when you come to a hospital, nine times out of ten you’re just quiet... And that’s it till you get to leave and you really don’t address the problem. So I think that … they will be in a more relaxed environment to honestly open up a little bit more” (Participant_35_Site_12).

Finally, several interviewees thought that the virtual format was transforming how Veterans were sharing experiences and emotions with one another. For example, one facilitator recounted that a Veteran in the group, who was talking about the goal of improving the rapport with his family, was able to show other participants a meal he had just cooked for his loved ones, resulting in supportive comments from others. Similarly, several interviewees mentioned that Veterans used the chat box to express support and exchange information, which, as one facilitator observed, is something that could be done without disrupting the flow of the conversation:

“…it’s interesting, like once people are sharing, people are also in the chat box, like saying like, ‘oh, you know, I had that experience too,’ and… so they know that they’re not alone. So I think that that is… sort of an added kind of layer of being online, where people can express support simultaneously as someone else is talking…” (Participant_10_Site_04).

Convenience

When we asked staff members about challenges with TCMLH groups prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous interviewees mentioned that it was hard to convince Veterans to commit to participating in multi-week in-person group sessions. With a few exceptions, the attrition rates were described as high across most facilities. Therefore, it is not surprising that the convenience of virtual TCMLH groups figured prominently in our interviews as the most commonly mentioned advantage of the format. Specifically, the lack of driving and other associated tasks (eg, looking for parking, sitting in the waiting room) was highlighted as a powerful advantage of virtually delivered TCMLH:

“I almost feel that the attendance is better. … Because the fact is that they can stay home, that they can do it from their kitchen table. They don’t have to drive 20 or 30 minutes here… to come see us. … They can just, okay, I can pop on real quick, and you know, it’s an hour, hour and fifteen minutes, hour and twenty minutes, and then they’re off, and then they can carry on about their day” (Participant_01_Site_01).

Many interviewees also felt that virtually delivered TCMLH may be a more feasible modality for several categories of people who might have difficulty attending in person, such as Veterans who work, have caregiving responsibilities, have a disability, and/or live in a rural area:

“[Tele-TCMLH would be advantageous for] any of our veterans who have limitations getting to and from the site. You know, some of them have mobility issues, transportation issues. Some live in a rural location, and we have several CBOCs that are several hours away from our main campus; so, it would be easier for those folks to participate in the classes, definitely” (Participant_34_Site_12).

In a somewhat distinct variation of this theme, several interviewees mentioned that the virtual format allowed facilities to increase enrollment by offering more classes simultaneously:

“I think that the flip side of… being in a virtual environment, is that before we didn’t have the option to run two, three, four classes a day, right? We’re still going to probably be limited on staff, right? …but the good thing about the virtual environment is that as the numbers increase with TCMLH, we can… easily increase the classes because they’re virtual. And… that’s just the best thing about it is that we have the opportunity to… take it to a whole different level in terms of the virtual environment” (Participant_20_Site_06).

Indeed, when we asked our interviewees to think toward the future, most enthusiastically supported the idea of VHA continuing to offer TCMLH in a virtual format even after face-to-face options return:

“I would honestly want to see both modalities still offered; be able to have the face-to-face group dynamics, mix in the VVC for the guys that for whatever reason can’t make it in, possibly even with a hybrid of some form where I’m sitting in a room with the group, and we have three guys that have called in” (Participant_02_Site_01).

Help in Overcoming the COVID-19 Isolation

Finally, staff members frequently observed that, at the start of the pandemic, many Veterans were hesitant to enroll in virtually delivered TCMLH groups, eager to “wait it out” until a face-to-face option became available, yet the subsequent rounds of outreach were increasingly more successful. Interviewees attributed this change to Veterans’ growing openness to the virtual format in light of the feelings of isolation brought on by the pandemic. One program manager aptly described the change in Veteran attitudes the following way:

“…as everybody realized that COVID was continuing and that they were still isolated, they decided that they wanted this information, and they realized that Whole Health and Taking Charge and talking about the stress and goals and how their health and well-being was being affected from this, they decided that they would rather attend these classes over the phone or via VVC because they realized that it would help them. And, so, it took off like nothing we ever saw before, way more interest in the Taking Charge… and we’ve had numbers that we haven’t had previously. And I think a lot of that is due to COVID and due to how this pandemic is affecting people and their lives, and they’re realizing it’s not going away; so, they want the resources that we provide in that class, and they realize that they need help and encouragement and information” (Participant_32_Site_11).

Indeed, several sites successfully recruited TCMLH participants during COVID-19 “comfort calls” (periodic check-ins with Veterans done by Whole Health partners):

“…when we were doing the compassion calls and reaching out to the Veterans to see you know and check on their well-being, some of those Veterans… who felt like they were shut in, when we made these… offers to them you … I think that they jumped at the opportunity because it made them not feel so alone and isolated” (Participant_27_Site_09).

Interestingly, however, at one site a facilitator observed a gradual drop in virtual TCMLH enrollment following an initial uptick. This trend was attributed to “competition” from other virtual groups at this site:

“…maybe the first 30 days… people wanted to take the groups, there were more people who were saying, hey, you know I’m more isolated, I need to be active, you know, I’m interested in the group… I think enrollment there was an uptick initially… You know, but I think what happened over time is… it wasn’t long before everybody else started running groups. …so, instead of the guys, you know, wanting more of our VVC group, now they had all kind of options for groups… So, after a while… participation started to wane a little bit on it because guys were kind of being overwhelmed with… group offerings through VVC” (Participant_03_Site_01).

Discussion

In this paper, we explored the perspectives of VHA staff members involved in running or supporting a Whole Health peer-led group for Veterans, “Taking Charge of My Life and Health” (TCMLH), after this group was shifted to a virtual format in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Describing virtually delivered TCMLH as a feasible and accessible modality, interviewees detailed factors that were helpful in the transition of service delivery format, as well as those that made the transition challenging. Moreover, many of the providers we spoke with described feeling that, when delivered virtually, the Whole Health group we focused on in this evaluation had something important to offer to Veterans, particularly those experiencing pandemic-induced isolation, anxiety, and other related psychosocial impacts. These findings align with descriptions of other health care systems’ experiences with rapidly shifting in-person group-based services to a virtual formal in an effort to contain and mitigate the impact of the pandemic. 14 As such, we contend that our insights are directly relevant to health care providers and leaders within and outside the VA and may inform the implementation of other patient-facing virtual programs broadly construed.

A prominent theme in our findings concerned the trade-offs of the virtual format for the group facilitator. On the one hand, our interviewees felt that running the group virtually may make it difficult to recognize non-verbal cues, an insight echoed in literature assessing virtually delivered psychotherapy, including one-on-one sessions.15,16 Similarly, the challenges of maintaining participant engagement during virtually delivered sessions are described in the growing body of research on telehealth psychotherapy and peer support groups. 16 On the other hand, our interviewees thought that the virtual format may allow the group facilitator to more effectively understand and react to participants’ facial expressions and/or gain deeper insight into their home environment if visible on camera, a finding also present in the literature.17,18 The ethical implications of the facilitator’s ability to observe participants’ environments are yet to be fully understood and require further research.

Encouragingly, our findings suggest that participating in group sessions virtually, from their home environment, may lead Veterans to reflect more deeply on their current situation, goals, and aspirations, which is a core goal of the group. Our interviewees conjectured that, when surrounded by personally salient cues, Veterans may feel a stronger sense of motivation and better understand barriers to making changes. This finding is echoed in the body of literature on behavior change and habit formation, which speaks to the importance of cues embedded in everyday environments for forming or undermining new habits.19,20 It is not necessarily the case that participating from one’s home would lead to improved insight and motivation for all participants. In fact, research shows that self-distancing (taking a step back to calmly reflect on a negative experience) may promote coping and emotional regulation for some.21,22 However, none of our interviewees raised this concern. Future work is needed to explore patient perspectives on impacts of their environment during group participation on goal setting and attainment to tease out the nuances of this relationship.

Another distinct advantage of the virtual format highlighted in our results was that some participants may feel less defensive and more willing to open up in virtual groups rather than in face-to-face ones. As others have noted,23-25 participation in the virtual format may be perceived as less stressful than in-person and, therefore, be more conducive to sharing. In juxtaposition, however, our findings also suggest that the virtual format may be more challenging for relationship-building between participants. While some papers echo this finding, 26 others challenge it: for example, a recent systematic review of telehealth support groups argues that many such programs were able to achieve bonding and group cohesion between participants. 27 Encouragingly, some of the interviewees in our evaluation did suggest that participants were able to form such bonds with their fellow virtual group-members, and in fact, some may have even been more motivated to do so.

The TCMLH curriculum and delivery are founded on the techniques and principles of peer support, health coaching, and health and wellness promotion that transcend the VHA context. Given the growing evidence that TCMLH groups are successful in helping participants achieve and sustain gains toward health care goals and well-being, they should be of high interest to health care organizations seeking to implement similar group-based programs. The factors we identified as helpful to the successful rapid implementation of virtually delivered, group-based, patient-facing interventions like TCMLH include (1) identifying standardized technology platforms amenable to the delivery of group-based curriculum, (2) ensuring a robust technical support infrastructure, and (3) adapting group facilitator delivery style to optimize engagement and minimize fatigue related to virtual meetings. These findings are aligned with other accounts in the literature, particularly the notion that identifying an appropriate technology platform and providing patients with the appropriate supports for using that platform are integral to the implementation of virtual services. 23 As the health care delivery landscape continues to adapt to changes realized during the heights of the COVID-19 pandemic and the momentum around virtual care delivery continues to build, lessons from VHA are well-positioned to help other health care organizations understand the important considerations related to implementing virtually delivered group programs to patients, either provider- or peer-delivered.

Limitations

We did not present Veteran perspectives in this manuscript, and these perspectives would have allowed for greater insights. Despite its features shared with other integrated health systems, 28 VHA is in many ways unique and Veterans are a unique population. Other health systems may encounter different challenges or need a different set of strategies to successfully implement Whole Health groups in a virtual format. At the same time, the contextualized description we offer in this manuscript should allow leaders in other health systems to distinguish between lessons that are directly applicable and ones that are less so.

Conclusion

Transitioning from in-person to virtual formats for health care can be challenging. Our findings show that shifting a Whole Health peer-led group (TCMLH) to a virtual format presented challenges yet was also feasible and offered several notable benefits. Standardized technology platforms amenable to the delivery of group-based curriculum, robust technical support, and adjustments to the group facilitators’ delivery style were particularly helpful for the rapid implementation of virtual TCMLH. The virtual format not only had advantages for participation and engagement but was also a good fit for helping Veterans cope with isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, with implications for counteracting isolation in other populations, as well. While VHA had to shift its delivery of Whole Health groups under very severe time constraints, other health care organizations are well-positioned to learn from VHA’s experiences in implementing a more intentional and thought-through roll-out of virtual groups like TCMLH.

Author’s Note

The contents of this paper do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-gam-10.1177_21649561211064244 for Lessons Learned From VHA’s Rapid Implementation of Virtual Whole Health Peer-Led Groups During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Staff Perspectives by Ekaterina Anderson, Kelly Dvorin, Bella Etingen, Anna M. Barker, Zenith Rai, Abigail Herbst, Reagan Mozer, Rodger P. Kingston and Barbara Bokhour in Global Advances in Health and Medicine

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT) and the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative; (QUERI) [PEC 13-001, “Evaluating VA Patient Centered Care: Patient, Provider, and Organizational Views”]. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Bedford Healthcare System.

ORCID iD

Ekaterina Anderson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2003-9805

References

- 1.Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole health: the vision and implementation of personalized, proactive, patient-driven health care for veterans. Medical Care. 2014;52(12):s5-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, Charns M, Kligler B. Transforming the veterans affairs to a whole health system of care. Medical Care. 2020;58(4):295-300. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.VA Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation. Taking Charge of My Life and Health - Facilitator Guide, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bovend'Eerdt TJ, Botell RE, Wade DT. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(4):352-361. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abadi MH, Barker AM, Rao SR, Orner M, Rychener D, Bokhour BG. Examining the impact of a peer-led group program for veteran engagement and well-being. J Alternative Compl Med. 2021;27(S1):S37-S44. doi: 10.1089/acm.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abadi M, Richard B, Shamblen S, et al. Achieving whole health: a preliminary study of tcmlh, a group-based program promoting self-care and empowerment among veterans. Health Educ Behav. 2021;109019812110110. doi: 10.1177/10901981211011043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darkins A. The growth of telehealth services in the veterans health administration between 1994 and 2014: a study in the diffusion of innovation. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2014;20(9):761-768. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers US, Birks A, Grubaugh AL, Axon RN. Flattening the curve by getting ahead of it: how the va healthcare system is leveraging telehealth to provide continued access to care for rural veterans. J Rural Health. 2021;37(1):194-196. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ourth HL, Heyworth L, Galpin K, Morreale AP. Virtual care revolution: impact on clinical pharmacy practices in the department of veterans affairs. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2021;4(8):1011-1015. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dryden EM, Bolton RE, Bokhour BG, et al. Leaning into whole health: sustaining system transformation while supporting patients and employees during COVID-19. Glob Adv Health Med. 2021;10:216495612110210. doi: 10.1177/21649561211021047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bokhour B, Hyde J, Zeliadt S, Mohr D. Whole Health System of Care Evaluation—A Progress Report on Outcomes of the WHS Pilot at 18 Flagship Sites. Veterans Health Administration: Center for Evaluating Patient-Centered Care in VA (EPCC-VA). https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/EPCC-Whole-Health-System-Evaluation_2020-01-27_FINAL.pdf (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton A. Qualitative Methods in Rapid Turnaround Health Services Research. Published. Health Services Research & Development Cyberseminar. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=780 (accessed on January 14, 2022).

- 13.Hamilton A. Rapid Qualitative Analysis: Updates/developments. Published. Health Services Research & Development Cyberseminar. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/cyberseminars/catalog-upcoming-session.cfm?UID=3846 (accessed on January 14, 2022).

- 14.Puspitasari AJ, Heredia D, Gentry M, et al. Rapid adoption and implementation of telehealth group psychotherapy during COVID 19: practical strategies and recommendations. Cognit Behav Pract. 2021;28:492-506. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2021.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Disney L, Mowbray O, Evans D. Telemental health use and refugee mental health providers following COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Soc Work J. 2021;49:463-470. doi: 10.1007/s10615-021-00808-w.| [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Springer P, Bischoff RJ, Kohel K, Taylor NC, Farero A. Collaborative care at a distance: student therapists’ experiences of learning and delivering relationally focused telemental health. J Marital Fam Ther. 2020;46(2):201-217. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langabeer JR, 2nd, Yatsco A, Champagne-Langabeer T. Telehealth sustains patient engagement in OUD treatment during COVID-19. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;122:108215. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell E. “Much more than second best”: therapists’ experiences of videoconferencing psychotherapy. Euro J Qual Res Psychol. 2020;10:121-135. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stawarz K, Gardner B, Cox A, Blandford A. What influences the selection of contextual cues when starting a new routine behaviour? An exploratory study. BMC psychology. 2020;8(1):29-11. doi: 10.1186/s40359-020-0394-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobias R. Changing behavior by memory aids: a social psychological model of prospective memory and habit development tested with dynamic field data. Psychol Rev. 2009;116(2):408-438. doi: 10.1037/a0015512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White RE, Kross E, Duckworth AL. Spontaneous self-distancing and adaptive self-reflection across adolescence. Child Development. 2015;86(4):1272-1281. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kross E, Ayduk O. Making meaning out of negative experiences by self-distancing. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2011;20(3):187-191. doi: 10.1177/0963721411408883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugarman DE, Horvitz LE, Greenfield SF, Busch AB. Clinicians’ Perceptions of Rapid Scale-Up of Telehealth Services in Outpatient Mental Health Treatment. Telemedicine and E-Health. 2021;27(12):1399-1409. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinberg H. Online group psychotherapy: challenges and possibilities during COVID-19-A practice review. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2020;24(3):201-211. doi: 10.1037/gdn0000140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sasangohar F, Bradshaw MR, Carlson MM, et al. Adapting an outpatient psychiatric clinic to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a practice perspective. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(10):e22523. doi: 10.2196/22523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozlowski KA, Holmes CM. Experiences in online process groups: a qualitative study. J Spec Group Work. 2014;39(4):276-300. doi: 10.1080/01933922.2014.948235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banbury A, Nancarrow S, Dart J, Gray L, Parkinson L. Telehealth interventions delivering home-based support group videoconferencing: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(2):e25. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson E, Solch AK, Fincke BG, Meterko M, Wormwood JB, Vimalananda VG. Concerns of primary care clinicians practicing in an integrated health system: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(11):3218-3226. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06193-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-gam-10.1177_21649561211064244 for Lessons Learned From VHA’s Rapid Implementation of Virtual Whole Health Peer-Led Groups During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Staff Perspectives by Ekaterina Anderson, Kelly Dvorin, Bella Etingen, Anna M. Barker, Zenith Rai, Abigail Herbst, Reagan Mozer, Rodger P. Kingston and Barbara Bokhour in Global Advances in Health and Medicine