Abstract

Society faces several major interrelated challenges which have an increasingly profound impact on global health including inequalities, inequities, chronic disease and the climate catastrophe. We argue here that a focus on the determinants of wellbeing across multiple domains offers under-realised potential for promoting the ‘whole health’ of individuals, communities and nature. Here, we review recent theoretical innovations that have laid the foundations for our own theoretical model of wellbeing – the GENIAL framework – which explicitly links health to wellbeing, broadly defined. We emphasise key determinants across multiple levels of scale spanning the individual, community and environmental levels, providing opportunities for positive change that is either constrained or facilitated by a host of sociostructural factors lying beyond the immediate control of the individual (e.g. social cohesion and health-related inequities can either promote or adversely impact on wellbeing, respectively). Following this, we show how the GENIAL theoretical framework has been applied to various populations including university students and people living with neurological disorders, with a focus on acquired brain injury. The wider implication of our work is discussed in terms of its contribution to the understanding of ‘whole health’ as well as laying the foundations for a ‘whole systems’ approach to improving health and wellbeing in a just and sustainable way.

Keywords: whole health, wellbeing, health care, education, planetary wellbeing

Introduction

Wellbeing causally affects health and longevity after controlling for health and socioeconomic status at baseline. 1 At a biological level, there is now compelling evidence for the interconnectedness of pathways subserving physical and mental health.2,3 Therefore, discussions about ‘whole health’ are wholly inadequate without the inclusion of wellbeing. The aim of this article is to highlight the importance of wellbeing towards ‘whole health’ by introducing theoretical insights from wellbeing science, including our own work. We then describe how we have applied this theory within the healthcare and education sectors in the UK, which in turn have helped to further clarify key concepts of our framework. Guided by social ecological theory,4,5 we argue for a more inclusive approach to whole health that encompasses concepts of individual, collective and planetary wellbeing and their interconnectedness. We begin by casting a critical eye on wellbeing as a ‘wicked problem’, 6 providing the motivation for and context within which we have sought to develop our GENIAL theoretical framework.

Problematising Health and Wellbeing

The knowledge and practices of modern medicine are founded, organised and influenced by extreme mind–body dualism, an approach that constrains thinking and approaches to treatment, while contributing to scepticism of non-biological explanations for illness such as social determinants. 7 By contrast, the World Health Organisation appears to advocate for materialistic monism, referring to health as ‘complete mental, physical and social wellbeing’. Professor Skrabanek reportedly joked that by this standard, health could only occur at the moment of mutual orgasm, 8 pointing out that the WHO definition also constrains opportunities for whole health, especially for the increasing numbers of people who must live with a chronic condition. The limitations of these two competing approaches – extreme dualism vs materialistic monism – highlight the utility of what has been described as ‘interactive dualism’, emphasising an interaction between body and mind, a consideration that has implications for treating the ‘whole person’ rather than a ‘diseased body’. 9 While research shows that people living with chronic conditions have tremendous potential for wellbeing,10,11 this potential is constrained by the pernicious impacts of social, economic and political power structures. This broader sociostructural context has led to a critique of wellbeing labelled as ‘pollyannaism’, 12 referencing the fictional character Pollyanna, an orphan girl who played ‘glad games’ to manage loss and social prejudice. In this regard, neoliberalism – a dominant political and economic ideology in many parts of the world, especially in the west – has contributed to gross socioeconomic inequalities and inequities. 13 Recent research has reported that neoliberal ideology increases the perception that one is in competition with others, increasing the sense of social isolation, which adversely impacts on individual wellbeing. 14 Such ideology has contributed to a commercialisation of wellbeing (e.g. ‘McMindfuness’), in which ‘wellbeing’ is stripped to its bare bones, and torn from its philosophical (and religious) foundations. This hijacking of wellbeing has led to criticisms arguing that ‘positive psychology is for rich white people’ 15 and that wellbeing is a casualty of modern consumer society. 16

The climate emergency 17 brings to light the glaring inconsistency between harnessing nature in service of individual health and wellbeing, while ignoring the impact of unrelenting business as usual, contributing to the unfolding climate catastrophe.18,19 Despite the economic slowdown associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, greenhouse gasses including carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide have all set new records; Greenland and Antarctica show new all-time record low levels of ice mass; ocean heat content and acidification have set new records; and livestock numbers now represent more mass than humans and wild mammals combined. 17

These issues emphasise the considerable complexity surrounding the construct of wellbeing – a ‘wicked problem’ 6 – that is difficult to define and avoids straightforward solutions. When considered in a wider context – a systems context – whole health cannot be achieved without planetary wellbeing, a concept recently defined as ‘the highest attainable standard of wellbeing for human and non-human beings and their social and natural systems’. 20 The newly coined concept of ‘planetary wellbeing’ is closely aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs), which recognise that human wellbeing is unachievable unless the Earth’s systems are preserved.

Theoretical Innovations

Psychological science is the discipline with which we are most familiar and are actively engaged; however, we have been inspired by and drawn on recent developments in the heterogeneous discipline of wellbeing science, characterised by a move beyond individual people, discipline, method and culture. 21 The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have reinforced the need to focus on self-transcendence, 22 social identity 23 and nature connectedness, 24 and related reflections on how wellbeing might be promoted within the context of the unfolding climate catastrophe. 25 Historically, psychological science has been restricted to individual wellbeing, but recent literature has emphasised interventions that target increasingly higher levels of scale beyond the individual including schools and universities (e.g. wellbeing literacy), workplaces (e.g. positive leadership), communities (e.g. volunteering, arts, culture, identities), cities (e.g. the ‘happy city’ initiative) and even nations (e.g. wellbeing public policy; UNSDGs).20,26 This work reflects efforts to support wellbeing through the development of nurturing environments at multiple levels and multidisciplinary contributions.

The recently proposed tridimensional model of behaviour, 27 including personal (self-care), social (caring for others) and physical environment (caring for the environment) components – consistent with our own GENIAL framework – emphasises that individuals must first recognise and satisfy their own needs in order to be able to care for others and protect the environment. Therefore, initiatives to improve wellbeing at an individual level contribute to increased wellbeing at the community and environmental level. This model is also consistent with the recently proposed concept of ‘planetary wellbeing’, 20 which encompasses three interconnected dimensions focused on individual (e.g. health, education, economic capacity and other elements required for a good life), social (including a focus on human rights, justice and grounds for a life of dignity and self-respect) and planetary dimensions, emphasising concern for the wellbeing of, in and for the planet. These multidisciplinary developments must now be synthesised in such a way that leads to interdisciplinarity and even transdisciplinary ways of working, 28 in order to produce new knowledge and ultimately, more effective interventions to promote whole health. Social ecological models may provide a means to better understand the complexity of wellbeing, by placing the individual within their social and natural ecologies.5,29 The individual is positioned within increasing phenomenological scales, extending to the ecosystem and the life course, highlighting systemic influences on wellbeing that also change over time (i.e. the chronosystem). This temporal dimension was explicit in earlier iterations of our framework, 3 while more recent iterations have emphasised the multi-levelled domains of wellbeing.18,19,30 Adopting a social ecological approach to wellbeing requires entrenched disciplinary and organisational silos to be overcome through silo-busting techniques that include a focus on values, reward and development of people, collaboration and leadership.18,31

Our Contributions to a Modern Science of Wellbeing

The GENIAL model

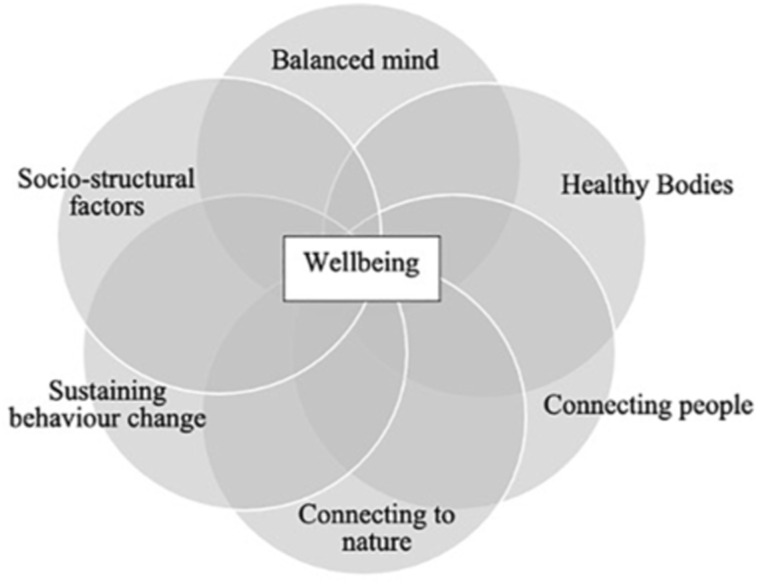

The complexity of wellbeing motivated us to reflect on an extensive body of scholarly work. We were struck by research that had been developed in relative isolation from each other. For instance, positive psychological interventions (PPIs) 32 are typically isolated from positive health behaviours, despite evidence indicating that such behaviours (e.g. physical activity) make an important contribution to positive psychological experience. 33 We were also struck by the emergence of related work focusing on social identity to improve health and wellbeing, 34 as well as increasing calls for a key role for psychology in managing the psychological consequences of the unfolding climate catastrophe.25,35 Yet, this body of work is isolated and has not been integrated into an overarching theory of wellbeing. These considerations motivated the development of the GENIAL framework3,18,19,30 (Table 1, Figure 1), which imposes an interpretative framework on the published literature, consistent with an abductive or explanatory approach to theory generation 36 that addresses criticisms, controversies and conundrums that have plagued wellbeing science. An abductive approach helps to make sense of ‘surprising, ambiguous or otherwise puzzling phenomena in order to fill the gaps in our beliefs, maintaining or restoring their coherence’. 37 This developmental process led to the proposal of the GENIAL model,3,18,19,30 a life-course theoretical framework through which wellbeing is realised. GENIAL is a biopsychosocial framework that is explicitly linked to a broader context including sociostructural factors, the neglect of which have had major implications for interventions to promote (health and) wellbeing. The GENIAL acronym refers to relationships between Genomics-Environment-vagus Nerve-social Interaction-Allostatic regulation-Longevity. The word ‘genial’ also means ‘friendly and cheerful’ in English, reflecting the important impacts of social relationships and community on human health and wellbeing. Recent iterations of our framework18,19,30 have emphasised core domains across which any budding transdisciplinary model of wellbeing must embrace and transcend. These domains comprise the individual (including a balanced mind and a healthy body), community (social connectedness), the environment (connection with nature), positive societal change and sociostructural factors.

Table 1.

A Summary and Overview of the GENIAL Framework (Kemp et al, 2018; fisher et al, 2019; mead et al, 2019, 2021), Emphasising a Multi-Levelled Approach to Promote Individual, community and Planetary Wellbeing.

| Core Domains | Focus | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Overview | Wellbeing is defined from a biopsychosocial ecological perspective, emphasising connectedness to self, others and nature, which may reflect a basic psychological need, supported by vagal function, a psychophysiological resource for connection. Individual wellbeing provides strong foundations for collective and planetary wellbeing, consistent with social ecological theory and systems thinking | Wellbeing is a ‘wicked problem’ associated with a host of challenges (e.g. conceptual; knowledge; implementation). The GENIAL model provides an overarching theoretical framework within which other theories are introduced. A driving motivation for developing the GENIAL model is a pressing need to overcome various interrelated scientific and societal challenges concerning the ‘wicked problem’ of wellbeing |

| Connecting to the self (the individual domain) | Capacity for individual positive change is highlighted with focus on a ‘balanced mind’ and ‘healthy bodies’. GENIAL emphasises the importance of both positive emotions and negative emotions for wellbeing and behaviour change. Key concepts include hedonia, eudaimonia and Martin Seligman’s integrative PERMA theory including positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning and achievement. Evidence linking psychological wellbeing to physical health is especially relevant. Positive health behaviours (e.g. healthy diet, physical activity, sleep quality) are introduced as major determinants of wellbeing. The vagus nerve is introduced as a structural link between mental and physical health (informed by the neurovisceral integration and polyvagal theories), representing a psychophysiological basis for self-connection | A focus on individual wellbeing is essential for collective and planetary wellbeing. Central to the GENIAL model is the role of the vagus nerve as the structural link between physical and mental health. This model serves to challenge the mismatch between the scientific evidence and the dogma of body/mind dualism, which can lead to siloed thinking, narratives that attenuate health-sustaining behaviours and missed opportunities for more effective interventions. The GENIAL model also provides a theoretical foundation on which more effective interventions can be built in keeping with a ‘whole health’ approach (see table 2 for examples of our recently developed interventions based on GENIAL). This work challenges misconceptions about wellbeing which is often construed as the absence of impairment, a perspective that constrains healthcare solutions. Major societal challenges relevant to this domain include the increasing burden of chronic disease |

| Connecting to others (the community domain) | Emphasis on social ties and relationships as a pathway to health and wellbeing, highlighting ‘relatedness’ as a basic psychological need. Self-determination and self-identity theory are key influences. Polyvagal theory provides a biopsychosocial framework for relatedness. Links between positive social relationships, physical health and longevity are especially relevant to this domain, as are the social determinants of health. Focus extends beyond personal relationships to include concepts such as social trust, social capital, social cohesion and social identity. An upward spiral relationship between positive emotions, perceived social connections and vagal function lays biopsychosocial foundations for social identity and collective wellbeing. Although constrained by sociostructural factors (see below), our framework encourages reflection on opportunities to overcome such constraints | The GENIAL framework outlines key determinants of wellbeing at multiple levels of scale and provides a framework to better integrate knowledge and practice across different levels of scale. Take, for example, the community and individual level. The role of the community is often under-appreciated by those tasked with supporting individuals to improve their wellbeing and social ties are often neglected in health and wellbeing interventions. Likewise, the health enhancing role of community lays beyond the control of individuals, and improving community wellbeing will require collaborative efforts and working across institutions. This insight is especially important given evidence that ‘community’ is deteriorating. Our work shows how gaps can be bridged across health services and community partners to reduce barriers for people who find it difficult to access the community independently and who often become marginalised. Major societal challenges relevant to this domain include inequalities and inequities as well as community deterioration, which leads to social isolation and loneliness |

| Connecting to nature (the environment domain) | Focus on nature connectedness and wellbeing. Connection to nature arguably provides a basic psychological need. Key theories include relate to biophilia, stress reduction and attention restoration. Positive (e.g. biophilia) and negative (e.g. solastalgia) earth emotions connect individuals to the environment. This domain also encompasses existential positive psychology (e.g. meaning in life), climate psychology (e.g. how to cope with difficult emotions associated with the climate challenge) and the new concept of ‘planetary wellbeing’, argued to be the ‘highest attainable standard of wellbeing’. Role of nature in promoting human wellbeing is also explored within the context of the climate catastrophe | The GENIAL framework outlines key determinants of wellbeing at multiple levels of scale and provides a framework to better integrate knowledge and practice across the different levels leading to more sophisticated (less siloed) theoretical insights and innovation in practice. Take, for example, the individual and the environment level. Humans have become increasingly disconnected from nature and connecting the individual to nature has been shown to reduce all-cause mortality. The promotion of nature connectedness via interventions or physical infrastructure is often neglected, however. GENIAL also addresses ethical considerations relating to harnessing natural environments to promote wellbeing while planetary wellbeing, which impacts the wellbeing of individuals and their communities. Recent findings have emphasised a role for nature connectedness in the promotion of pro-environmental behaviours in addition to wellbeing, laying key foundations for reflecting on how wellbeing might be improved while also contributing to wider efforts to manage major societal issues including the complex inter-related issues associated with climate change, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation |

| Positive change | Behaviour extending to societal change. Components of successful behaviour change including motive, willpower, habit, resources, environmental and social influences. Self-determination theory and satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Multi-levelled societal change within individual, community and environment domains. Emphasis is placed on the vast capacity for individual change drawing on behaviour change and goal setting theories, despite societal challenges and sociostructural constraints, which individual actions (e.g. volunteering, activism) may help to tackle. Population-wide societal change through, for example, ‘psychological boosting’ emphasises a capability approach to building societal wellbeing through, for example, education, health, capacity building and wellbeing public policy | The GENIAL framework includes behaviour change as one of its core domains appreciating the inherent disconnect between what people know and what people actually do. The intention-behaviour gap is a major barrier to translating evidence into sustained practice. Nonetheless, institutions concerned with health and wellbeing continue to engage in ‘information providing campaigns’ to inform behaviour change which are often ineffective. GENIAL deals with efforts to change behaviours at multiple levels of scale drawing from behavioural change theory thereby presenting a framework which identifies core determinants of wellbeing at multiple levels of scale as well as identifying factors and evidence-based strategies that lead to sustainable behaviour change and thereby reduce the intention-behaviour gap. Models of systems change (e.g. nonviolent civil disobedience; the transition movement; flatpack democracy) are also relevant to this section, as well as a focus on complexity theory |

| Sociostructural and contextual factors | Wellbeing is embedded within, constrained and facilitated by a range of factors (e.g. social, political, economic) and contexts (culture and historical). Consideration of sociostructural factors arising across individual (e.g. health, education, affordable housing), community (e.g. societal concerns for human rights, justice and democracy) and environment (e.g. Earth’s natural systems) domains provide a foundation for a cultural shift towards positive change. Focus includes consideration of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG’s) | While sociostructural factors constrain wellbeing, there is tremendous capacity for individuals, organisations and communities to contribute to collaborative efforts to ameliorate those constraints. The GENIAL model encourages reflection of factors that determine health and wellbeing beyond the control of individuals calling for a multiple pronged approach to support whole health in order to mitigate major societal challenges. We have described ways in which we have sought to reduce inequity caused by ‘disability’ and financial constraints in table 2. For example, clinicians and academics working to increase access to green and blue spaces for people with chronic conditions by reducing barriers to access as a function of disability or financial constraints. Major societal challenges relevant to this domain include inequalities and inequities |

Figure 1.

Summary of the core theoretical components underpinning our interventions, integrating insights from psychological science with developments across multiple disciplines spanning the individual, community and the environment.

The capacity for individuals to promote their own wellbeing is much greater than their capacity to promote collective wellbeing, which is greater than the capacity to promote planetary wellbeing. Regardless of those constraints, there is tremendous scope for individuals themselves to promote individual wellbeing within each of those domains, alongside larger collaborative efforts (e.g. community partnerships; collaborative working across disciplines; activism) for successful adaptation to various societal challenges (e.g. burden of disease, climate change). We will now describe how we have started to apply this theory through the development of initiatives to promote whole health, laying foundations for wellbeing, positive change and societal transformation. Table 2 summarises a range of interventions that we have developed in partnership, describing how each intervention maps onto the core theoretical domains of our wellbeing framework.

Table 2.

Mapping Education and Healthcare Sector Interventions Onto our Theoretical Model of Wellbeing.

| Intervention | Balancing Minds | Promoting health | Connection to others and community | Re/connecting to nature | Sustaining change | Socio-structural | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wellbeing Science Module for University Students1,2 Description: A 5-week Wellbeing Science module for third year university undergraduate psychology students. ‘Since beginning the module, I have been given a new lease of life…’ | Capacity for individual positive change is highlighted with a focus on ‘balanced minds’. Three major positive psychological theories are introduced: hedonic theory (e.g. Fredrickson, Diener), integrated theory (Seligman) and eudaimonia (Ryff, Wong). Students are encouraged to commit to a positive psychological intervention including, for example, working on character strengths, three good things exercise and breath-focused meditation. | Capacity for individual positive change is highlighted with a focus on ‘health behaviours’. The vagus nerve is introduced as a structural link between mental and physical health. A key role for positive health behaviours on wellbeing is discussed consistent with a focus on ‘body’ and ‘mind’. Students are encouraged to select and commit to practicing at least one positive health behaviour such as regular physical activity or improving diet. | Students are introduced to the role of social relationships and networks in support of psychological wellbeing. Key theories introduced include Polyvagal Theory, Social Wellbeing and Social Identity Theory. Students select an intervention relevant to the community domain (e.g. volunteering). Patient representatives, clinicians and community providers provide guest lectures to further engagement and connections with community | Discussions include the relationship between nature connectedness and wellbeing in the context of the unfolding climate catastrophe. The relationship between positive psychology, pro-environmental behaviours and environmental sustainability is emphasised. Key theories include Social Ecological Theory, Biophilia and Attention Restoration Theory. Students select one intervention to practice (e.g. nature-based mindfulness). | Behaviour change and Goal Setting Theory is introduced as well as determinants of successful behaviour change including positive psychology inspired models. Students are encouraged to reflect on how they might sustain positive changes with regards to the interventions they have chosen to practice over the course of the intervention. | Sociostructural and socio-contextual influences on wellbeing are discussed at each level of scale with room for reflection on opportunities to ameliorate sociostructural issues and wider societal challenges, for example, by committing to a cause or initiative students are passionate about. This provides an opportunity to realise a sense of meaning and wellbeing despite hardship and suffering. | A total of 132 students enrolled in a 5-week module, 37 of whom (28%) voluntarily completed a brief survey before and after the module. Baseline wellbeing was reduced compared to published norms (p=0.002, BF10=20.81), and this difference was ameliorated after students had completed the wellbeing science module (p=0.186, BF10=0.406). Within subject comparison further indicated that wellbeing had improved on module completion (p=0.012, d=0.385, BF10=3.831). (See Kemp et al., 2021; Kemp and Fisher, 2021 for details). |

| Positive Psychotherapy Intervention c Description: 8-week (2 hrs a week) group-based Positive Psychotherapy Intervention for people with ABI ‘I met a lot of friends. And some that I contacted outside of the group because they understood the injury & helped me through a difficult time.’ (Tulip et al., 2020) | Uses principles and exercises from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Mindfulness and Positive Psychology to facilitate adjustment, acceptance and management of difficult emotions. Positive psychological interventions including character strengths, three good things exercise, savouring etc., are introduced and practiced building positive emotion. Meaning is explored through value identification exercises and use of Character Strengths. | The vagus nerve is introduced as a structural link between mental and physical health. Mind–body connection using mindfulness techniques and deep breathing to activate parasympathetic response are practiced. The importance of health behaviours is introduced in relations to wellbeing, general health and brain injury recovery. Goal setting is used to tailor an individualised plan for group members centred around value-based living. | Providing opportunities for social connection through group work. Promoting social capital and community cohesion (peer support, interaction) and identity reconstruction post-brain injury (‘shared experience’). Positive psychology interventions introduced to facilitate social connection (i.e. loving kindness meditation, laughing yoga, acts of kindness). Goals identified to enhance social connection and links to health and wellbeing made explicit. The benefits of community integration made explicit as well as ways in which they can engage in their communities after the group. | Providing information about links between wellbeing and nature connectedness. Utilising nature-based meditations, three good things in nature exercise and nature journaling. The relationship between positive emotions, pro-environmental behaviours and environmental sustainability is discussed and linked to local community initiatives which would support individual and planetary wellbeing. | Identification of values. Techniques to convert values into actions and meaningful goals. Goal setting techniques (e.g. S.M.A.R.T. goals) used to break down goals into manageable steps. Five determinants of successful behaviour change are explored and incorporated into individualised behaviour change plans. Barriers to carrying out the plan are discussed as well as factors that increase the likelihood of long-term behaviour change. | Available to all as part of the National Health Service which in the UK is free at the point of entry (with some exceptions). Participants supported with transport if needed by clinicians or travel costs can be reimbursed by the Health Care Travel Cost Scheme, if a person is in receipt of qualifying welfare benefits or allowances. | Qualitative analysis of this intervention for people living with ABI identified 6 overarching themes of ‘Empowerment’, ‘Social Opportunity’, ‘Coping’, ‘Cultivation of Positive Emotion’, ‘Consolidation of skills’ and ‘Barriers to Efficacy’ (Tulip et al., 2020). We have received funding from the Welsh Government to carry out a mixed-methods feasibility RCT on this novel intervention which is in progress. |

| Surf Therapyd,e | Balanced Minds | Promoting Health | Community Connection | Nature connection | Sustained change | Sociostructural | Outcome |

| Description: A 5-week surf Therapy intervention in partnership with ‘Surfability’ ‘[The ocean is] just so calming… I just feel as if I’m connected’. | Opportunities for positive emotion through socialisation, achievement and exercise. Opportunity to find meaning through engaging with meaningful activity and social group. Opportunities for the positive reconstruction of identity post-brain injury. Clinicians present in the group encourage participants to be mindful whilst in the water. Clinicians also help reduce participants' anxiety at the start of the group by talking through concerns/thoughts and help patients implement techniques to manage difficult emotions in the moment. Interventions linked to value-based living goals. Participants learn a new skill and have the opportunity to develop a sense of mastery and increased autonomy over the duration of the course. Creates a context for positive emotion, meaning and achievement. | Introduces participants to a new outdoor exercise. Experience the benefits of surfing, body boarding and swimming. Opportunity for weekly exercise. Support to maintain surfing post group. Promotes surfing as a potential cognitive remediation strategy as well as a strategy to improve physical and mental health. Ability to support people of all abilities to surf using adapted surfboards, paddleboards, seating, beach 'wheelchairs’, wetsuits with additional zips, heated neoprene vests and disabled changing facilities which even include a ceiling hoist. | Promoting social capital (i.e. sharing experiences, surfing tips), cohesion (participants and their families meet other individuals with ABI, watch and encourage each other). Participants also have the opportunity to have coffee together following the group; another chance to form bonds. Social capital is also facilitated by partnership working between and across organisations (sharing learning and reducing professional and organisational silos). Regular feedback from service users shapes the structure and content of the groups facilitating horizontal exchange. | Takes place on a beach in the Gower Peninsula in South Wales, UK, area of outstanding natural beauty. Participants spend a significant amount of time in the ocean and feel the benefits of blue spaces. Several participants report not having been in the sea since childhood. Links between nature connectedness, health and wellbeing made explicit to encourage nature connectedness as a strategy to increase wellbeing and resilience. | Participants are taught basic surfing and safety skills so they can continue their hobby beyond the group. Support regarding wetsuits, buying surfboards etc. Depending on ability and capacity, participants are offered the opportunity to continue as a volunteer. Some group members have formed a group that meet to participate in beach cleans, others volunteer with Surfability and some meet socially to surf with others or have started going surfing with friends or families. | Clinicians and community providers apply jointly for grant funding so that an intervention, which would otherwise be financially inaccessible to many participants, can be accessed. The intervention creates opportunities for participants (many who do not have access to private gardens) to regularly capitalise on the health beneficial effects of spending time in nature. Staff typically provides transport for service users to help reduce barriers to access. | Qualitative analysis recently submitted for publication identified several themes including: ‘Facilitating Trust and Safety’; ‘Managing and Accepting Difficult Emotions’; ‘Facilitating Positive Emotion, Meaning and Purpose’, ‘Building Community through Social Connection’, ‘Engaging and Connecting to Nature’; ‘Positive Change’ and ‘Barriers and opportunities. We are carrying out a quantitative analysis of this project which is currently in the data collection phase. We have received funding from Welsh Government/big lottery funding schemes to run collaborative interventions with Surfability for another two years. |

| Bike-Ability f Description: Partnership between ‘Bikeability’, a local Community project and NHS. The group was 1.5 hours long and typically runs every week for 5-weeks ‘… what I enjoyed the most was going out & having a purpose. Going out and doing something’. | Opportunity for positive emotion via socialisation, achievement and exercise. Opportunity to find meaning by engaging in meaningful/goal-directed activity – group can promote a positive reconstruction of identity post-brain injury. Clinicians help reduce participants’ anxiety at the start of the group by talking through concerns/thoughts; helping patients implement techniques to manage difficult emotions in the moment. Participants learn a new skill or rediscover an old interest and have the opportunity to develop a sense of mastery and increased autonomy over the duration of the course. | Opportunity for participants to experience the benefits of exercise. Promotes cycling as a hobby and a cognitive remediation strategy. The link between physical exercise and wellbeing is made explicit. | Opportunity to meet others within the community project. Promoting social capital (i.e. participants and their families meet and can share coping techniques, experiences and tips for cycling). Social connection is facilitated throughout the group, but participants have the opportunity to stop for coffee together halfway through each session, thereby increasing opportunities to form connections. Staff at bike-ability learns more about brain injury and how to support people. | The group takes places in nature (forestry trials and sea front tracks). Opportunity to experience the benefits of green spaces. Links between nature connectedness, health and wellbeing made explicit to encourage nature connectedness as a strategy to increase wellbeing and resilience. | The groups build resources (confidence, competence) to encourage participants to continue cycling independently after the group has ended. Participants have the option to continue accessing bike-ability independently if adapted bikes are needed. Several participants have gone on to purchase adapted bikes to use socially after the project or have made friends with other group members who now cycle together outside the group. | Clinicians and community providers apply jointly for grant funding so that an intervention, which would otherwise be financially inaccessible to many, is accessible to all. Staff typically provides transport for service users to reduce barriers to access. Provides opportunities for engagement in green and blue spaces that many of our service users cannot easily access as a function of socioeconomic barriers. Service users can use a range of accessible equipment free of charge (i.e. bikes, electric bikes, tandem bikes etc.). | Recently evaluated as part of a wider multi-intervention study during the COVID-pandemic (Wilkie et at. 2021). |

| Down to earth (Gibbs et al., in preparation) Description: Partnership between Down to Earth a local not-for-profit organisation and NHS. Service users engage in outdoor sustainable construction and Nature conservation, 4 hours a week for 8–12 weeks. ‘Things like this make you change your mind from halfempty, to halffull’. ‘It has been inspirational for us all, it has given us a direction’. | ‘Green care’ intervention provides a context for the experience of positive emotions, achievement and meaning through learning new skills and contributing to sustainable building projects or local conservation projects. Participants can gain accredited certificates in sustainable building, health and safety and/or woodland management. Courses typically include an adventure week where the group chooses to engage in an adventure activity (climbing, river walking, sailing) which provides a context for achievement and positive emotion. | Participants learn about healthy sustainable growing and healthy eating as part of sustainable living skills. Participants engaging in behaviours including woodland management in local green spaces and sustainable building on Down to Earth builds. The majority of tasks involve physical activity. | Social capital is facilitated by partnership working between and across organisations. All organisations learn about brain injury rehabilitation, pro-environmental behaviours and theoretical underpinning of wellbeing. The intervention is co-constructed across agencies. Social cohesion is facilitated as parties work together towards a shared goal – sustainable wellbeing. Group work provides opportunities for friendships, support and mutual learning. Participants can continue to volunteer with Down to Earth after completing the project. | Takes place mostly outdoors in the Gower Peninsula in South Wales, UK, area of outstanding natural beauty. Introduces participants to sustainable Behaviour through teaching them (through doing) about sustainable building and living and engaging them in local conservation initiatives. Links between nature connectedness, health and wellbeing made explicit to encourage nature connectedness as a strategy to increase wellbeing and resilience. | Participants can become part of the ‘Down to Earth’ Community’ whereby they are invited to support Down to Earth in various projects once a month on a Saturday. Moreover, there are links to other pro-environmental agencies for volunteering as well as some volunteering opportunities within Down to Earth. Many of our service users have continued to volunteer with Down to Earth years post-discharge reporting that they feel a sense of belonging there. | Clinicians and community providers apply jointly for grant funding so that an intervention, which would be financially inaccessible to many, is accessible to all. Staff typically provides transport for service users to reduce barriers to participation. Accredited qualifications are paid for through grant funding. Many of our service users do not have easy access to green spaces. This project provides opportunities for nature connection often prohibited as a function of socio-structural barriers. | Unpublished qualitative analysis of this intervention for people living with ABI identified 6 themes: ‘Increased Positive Experiences’, ‘Empathetic Environment’, ‘Acceptance’, ‘Positive Relationships’, ‘Personal Development’, ‘Achievement’ and ‘Barriers and opportunities. Participants gain an accredited certificate. Participants are able to access and engage with the Down to Earth community and initiatives post-discharge. A qualitative analysis is currently being written up for publication. |

| Co-designing Assistive Technology g,h Description: Patients with chronic conditions work with a clinical scientist to codesign technology to overcome difficulties and barriers to participation. ‘A hope, that this is not going to mean the end of everything. It doesn’t mean it’s the end of your usefulness you know, and your feelings of self-worth...’ | Working with patients to understand how their unique difficulties impact on everyday life and discussing design solutions together to reduce the impact of their condition and promote participation. Feedback from the pilot service evaluation showed that this way of working increased positive emotions and coping and reduced cognitive demands. Participants described an increased sense of autonomy (being able to sign cheques; make dinner etc.). | The aim of the initiative is for service-users to be able to overcome barriers to participation including engaging in positive health behaviours. For instance, customised seating for a surfboard to help a service user access surf therapy. Another participant reported that an assistive device helped her administer medication independently (delivered in a spray canister which she did not have the strength to use). This meant she could better manage her pain so her sleep quality improved. | Participants described the benefits of working closely with their clinicians to design solutions tailored to their needs. They felt valued and heard. Partnership working between the health service and university was instrumental for the development and implementation of solutions. These examples demonstrate the value of relationships in underpinning innovation and joined up working across systems. Participants reported that the devices helped support community participation by helping them overcome barriers. | Not specifically designed to support nature connection, although there is capacity to do this by reducing barriers to participation in blue and green spaces. For example, making adaptive seating for surf boards which this service has been involved in. | The intervention facilitates behavioural change by reducing barriers to change. For example, all the participants noted that the assistive devices they had co-designed had helped reduce barriers to meaningful or social activity. For example, helping children with homework and going out to restaurant with friends and family. | It is our vision that tailored assistive technology provision would be available to people with chronic conditions through the NHS and social services. We are working towards evidencing this approach such that people who need these devices are able to access them regardless of their financial circumstances. We summarise major barriers to the use of assistive technology in our meta-synthesis (Howard et al., 2020). | A recently submitted study described this intervention including the products that were co-designed, the impact on participants (of the products themselves and the co-creation experience) as well as a cost analysis of the process. Qualitative data of the impact of these coproduced designs include: ‘Regained Function’, ‘Additional Health Benefits’, ‘Increased Independence’, ‘Increased Coping and Positive Emotions’ and ‘Reduced Mental Load’. A larger mixed-methods study is in progress. |

aKemp A, Mead J, Sandhu S, Fisher Z. Teaching wellbeing science. Framework OS, ed. Published online 2021. https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/e7zjf

bKemp AH, Fisher Z. Application of Single-Case Research Designs in Undergraduate Student Reports: An Example From Wellbeing Science. Teach Psychol. Published online 2021:009862832110299. doi:10.1177/00986283211029929

cTulip C, Fisher Z, Bankhead H, et al. Building Wellbeing in People with Chronic Conditions: A Qualitative Evaluation of an 8-Week Positive Psychotherapy Intervention for People Living With an Acquired Brain Injury. Front Psychol. 2020; 11:66.

dWilkie L, Arroyo P, Conibeer H, Kemp AH, Fisher Z. The Impact of Psycho-Social Interventions on the Wellbeing of Individuals With Acquired Brain Injury During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021;12:648286. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648286

eGibbs K, Fisher Z, Wilkie L, Kemp A. Riding the Wave into Wellbeing: A Qualitative Evaluation of Surf Therapy for individuals Living with Acquired Brain Injury. Submitted. 2021.

fWilkie L, Arroyo P, Conibeer H, Kemp AH, Fisher Z. The Impact of Psycho-Social Interventions on the Wellbeing of Individuals With Acquired Brain Injury During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021;12:648286. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648286.

gHoward J, Fisher Z, Kemp AH, Lindsay S, Tasker LH, Tree J. Exploring the barriers to using assistive technology for individuals with chronic conditions: a meta-synthesis review. Disability & Rehabilitation Assistive Technology. Published online 2020:1-19. doi:10.1080/17483107.2020.1788181

hHoward J, Tasker L, Fisher Z, Tree J. (2021). Assessing the use of co-design to produce bespoke assistive technology solutions within a current healthcare service: a service evaluation.Submitted.

Application to Education

A focus on wellbeing, broadly defined, in university student populations is important because students are a high-risk population for mental health conditions. Critically, levels of mental distress are increasing, and have been doing so even prior to the COVID pandemic. 38 Depression and suicide-related outcomes in university undergraduate students have a pooled prevalence of 21%, 39 which is considerably higher than the point prevalence estimate of depression in the general population, estimated at 12.9%. 40 In response, we have developed a five-week module on wellbeing science that has been structured around the GENIAL framework.41,42 This module promotes a sense of connectedness to self (individual wellbeing), others (collective wellbeing) and nature (planetary wellbeing), consistent with social ecological theory. Students are introduced to the concept of ‘sustainable’ happiness and wellbeing, which has been defined in several different – yet complementary – ways. Students learn how to ‘sustain’ improvements to wellbeing by drawing on theories of behaviour change 43 while also placing happiness and wellbeing within the context of environmental ‘sustainability’, 44 in which strategies to promote wellbeing do not involve the exploitation of other people, the environment or future generations. Students are encouraged to identify activities to promote their mental and physical wellbeing (through interventions to increase positive affect 32 and/or positive health through, for example, physical activity 33 ); community wellbeing (e.g. orientation to promote good 45 ) and planetary wellbeing (e.g. nature-based mindfulness 46 ) while reflecting on how they might work towards overcoming the many sociostructural constraints to wellbeing through, for example, contributions to social change (e.g. volunteering; civic engagement; activism) through commitment to something greater than oneself (i.e. self-transcendence). 22 Wellbeing is therefore broadly defined and characterised by a focus on multi-levelled perspectives, ensuring that there is scope to improve the wellbeing of students themselves, while also encouraging students to reflect on how they might contribute to collective and planetary wellbeing, supporting efforts for positive societal change.

The impact of the intervention was evaluated during the COVID pandemic when university students faced a unique set of stressors. 41 As well as individual student reports of impact, we have now reported promising group-wise evidence for the beneficial effects of our module on student wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. 41 This includes evidence from pre-post within-subject comparisons and convergent findings relating to comparisons with nationally representative samples. Together, these findings demonstrate the beneficial impact our module has had on student wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerging research has highlighted a variety of factors to have protected wellbeing during the pandemic, 47 including tragic optimism, gratitude, meaning in life, physical health, social cohesion and identity and nature connectedness, all concepts that have been integrated into our module, amongst others. Importantly, we are continuously improving our module based on student feedback and recent developments in the field, consistent with an action research approach to curriculum development, professional development and a scholarly research agenda to improving wellbeing in university student populations. 42 This process also led us to incorporate ideas on how individuals might contribute to positive societal change (e.g. volunteering; activism; psychological boosting) leading to further development of our theoretical model. (See Table 1 for summary of key principles). Our own findings together with those published in the wider literature highlight the capacity of the individual to promote their own wellbeing within the context of their lived environment, while also contributing to collective and planetary wellbeing. Although individuals play a relatively small role in improving collective and planetary wellbeing, adopting a relational approach to wellbeing by connecting to self, others and nature will be instrumental for driving much needed societal transformation in response to major societal challenges. Critically, ‘bottom up’ approaches will be rendered much more efficient if accompanied by ‘top down’ initiatives and strategies at multiple levels of scale, including, for example, community-led change (e.g. the Transition movement), policy-led change (e.g. Wellbeing Public Policy) and legislative-led change (Wellbeing for Future Generations Act).

Application to Healthcare

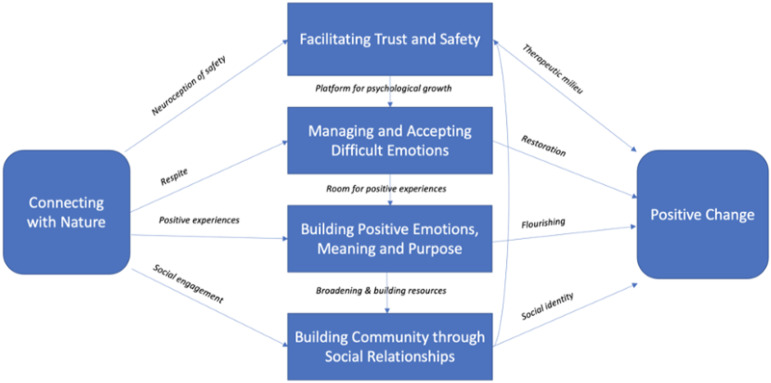

We recently described several factors that have constrained the long-term care of people living with chronic conditions 30 including definitional issues focusing on complete mental, physical and social health, a goal that is seldom possible for people with long-term chronic conditions and inadequate models of healthcare including the ‘acute medical model’, which is underpinned by a ‘find’ and ‘fix’ deficit reduction approach that is incongruent with a ‘whole health’ approach because the absence of impairment is not representative of whole health. Cartesian dualism is often inherent in the way that health systems define, treat and design services which can lead to siloed thinking and narratives that actually attenuate health-sustaining behaviours. 48 Factors such as these ultimately result in failure of public healthcare to meet the long-term needs of those living with chronic conditions. We have applied core principles from our GENIAL framework (Table 1) to inform a more holistic approach to the rehabilitation of people living with Acquired Brain Injury (ABI), in particular. This has involved designing more holistic models of health care within our clinical service and developing collaborations with community providers to bridge the gap between the health service and the community. This is needed as many people with chronic conditions struggle to access their local communities independently post-discharge, 49 leading to social isolation and loneliness – major determinants of ill-health and premature mortality. 3 We have now established a healthcare hub networked to the university and a wide range of local area initiatives that together better support sustainable community integration and wellbeing, in keeping with local top down initiatives advocating for a systems approach (i.e. A Regional Collaboration for Health, ARCH: http://arch.wales/en/index.htm). Table 2 summarises these initiatives which include positive psychotherapy, assistive technology co-design, nature-based exercise and local conservation projects. By means of example, we describe in more detail one of these initiatives: a Surf-Therapy collaboration between academics, clinicians, patients and the local Community Interest Company, Surfability (https://surfabilityukcic.org). At an individual level, surf therapy involves explicitly promoting the benefits of exercise while clinicians work to facilitate feelings of positive emotion, meaning and achievement. At a community level, exercise provides a context for creating positive social relationships and eliciting feelings of belongingness and acceptance (social cohesion). Surf therapy brings together individuals with ABI (and their families) from diverse backgrounds, helping to promote (bonding and bridging) social capital and a strong social identity. At an environmental level, participants are engaged in nature-based exercise, facilitating the experience of wellbeing, which has also been shown to promote the emergence of pro-environmental behaviours. 50 Mindful of the need to overcome sociostructural constraints to participation, clinicians and community providers have secured competitive grant funding to develop and deliver an intervention that would otherwise be inaccessible to many participants. Figure 2 provides a theoretical model for the benefits of surf therapy in people living with ABI, illustrating relationships between identified themes from unpublished qualitative analysis and potential underlying mechanisms identified from the available literature.

Figure 2.

A proposed theoretical model for the benefits of surf therapy in people living with Acquired Brain Injury, illustrating potential relationships between identified themes and potential underlying mechanisms

Discussion and Conclusion

We have sought to promote ‘whole health’ in a coordinated way by moving from theory to application and back to theory. Our work in the education sector has focused on building wellbeing in university students, providing opportunities to flourish through connections to self, others and nature, and a commitment to something greater than oneself (i.e. self-transcendence). 22 Our service evaluation work demonstrates how new interventions based on our theoretical framework have been translated into clinical practice and tailored to meet the needs of specific populations, providing opportunities for the experience of multiple determinants of wellbeing despite life changing conditions. Evaluations of our interventions have helped to refine our model, and these refinements subsequently led to further improvements in interventions themselves, through co-creation, abduction and action research methods.

Our GENIAL framework has helped to frame and contextualise the construct of wellbeing, laying the foundations for thinking differently about how ‘whole health’ might be promoted by reflecting on individual, collective and planetary wellbeing. We have been inspired by recent developments in wellbeing science including a move beyond individual people, discipline, method and culture, encompassing developments in psychological science, 21 wellbeing public policy 51 and the pursuit of sustainable development goals in higher education. 20 Our GENIAL model has provided a useful framework for reflecting on action at multiple levels, that include the individual, but also extend into what Bronfenbrenner described as the ‘exosystem’, 4 which refers to settings or structures that function independently of the individual, but that nevertheless impact on settings in which the individual lives.

In conclusion, we have argued that wellbeing plays a key role in ‘whole’ health and have shown how the GENIAL framework provides a strong basis on which health and wellbeing might be improved at multiple levels of scale in a just and sustainable way. Our work has involved: 1) developing a theoretical framework (the GENIAL model) to better frame our understanding of the complexity of wellbeing and develop novel interventions, 2) identifying funding and collaborative opportunities across organisations and disciplines to overcome barriers and practical challenges, 3) co-creating and co-delivering innovative interventions alongside community partners, 4) evaluating outcomes through multi-pronged research methods to inform continued refinement of our framework and interventions and 5) engaging with multiple stakeholders. This work provides a step toward a transdisciplinary model of wellbeing and way of working that has facilitated a reimagining of what it means to experience health and wellbeing, which often includes hardship and great suffering.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our PhD Students, Jessica Mead, Katie Gibbs, Jonathan Howard, Lowri Willkie and Sanjeev Sandu whose work as part of our GENIAL science team has contributed to our knowledge and thinking. We would like to thank our colleagues at Swansea University, Swansea Bay University Health Board and Fieldbay Ltd, who have co-funded our PhD students and recognised and promoted our work through various awards including the University Research and Innovation Award for Outstanding Impact on Health and Wellbeing (2018), the Swansea Bay University Health Board Chairman’s VIP Award for Commitment to Research and Learning (2018) and Swansea University Morgan Advanced Studies Institute (MASI) Summer of Hope Award (2021) to host a 2-day student-led wellbeing symposium. Finally, we would like to express our heartfelt thanks for the support of our service users, students and community partners who have worked with us and given so much of their time and energy to support our research agenda.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: We have built a novel and innovative positive psychotherapy intervention that is based on our GENIAL theoretical framework. This intervention was supported by grant funding from the Health and Care Research Wales through the Research for Public Patient Benefit Scheme (RfPPB-18-1502).

ORCID iDs

Andrew H Kemp https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1146-3791

Zoe Fisher https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8150-2499

References

- 1.Diener E, Chan MY. Happy people live longer: subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Appl Psychol: Health and Well-Being. 2011;3(1):1-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kemp AH, Quintana DS. The relationship between mental and physical health: Insights from the study of heart rate variability. Int J Psychophysiol. 2013;89:288-296. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kemp AH Arias JAand Fisher Z. Social ties, health and wellbeing: a literature review and model. In: Ibáñez, A, Sedeño, L, García A, (eds). Neuroscience and Social Science, The Missing Link. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing; 2017:Vol 59, 397-427. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1977;32(7):513-531. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.32.7.513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lomas T. Positive Social Psychology: A Multilevel Inquiry Into Sociocultural Well-Being Initiatives. Psychol Publ Pol Law. 2015;21(3):338-347. doi: 10.1037/law0000051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bache I, Reardon L, Anand P. Wellbeing as a Wicked Problem: Navigating the Arguments for the Role of Government. J Happiness Stud. 2016;17(3):893-912. doi: 10.1007/s10902-015-9623-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkman LF. Social Epidemiology: Social Determinants of Health in the United States: Are We Losing Ground? Annu Rev Publ Health. 2009;30(1):27-41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith R. The end of disease and the beginning of health. 2008. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2008/07/08/richard-smith-the-end-of-disease-and-the-beginning-of-health/. Acessed April 25, 2019.

- 9.Switankowsky I. Dualism and its Importance for Medicine. Theor Med Bioeth. 2000;21(6):567-580. doi: 10.1023/a:1026570907667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tulip C, Fisher Z, Bankhead H, et al. Building Wellbeing in People With Chronic Conditions: A Qualitative Evaluation of an 8-Week Positive Psychotherapy Intervention for People Living With an Acquired Brain Injury. Front Psychol. 2020;11:66. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkie L, Arroyo P, Conibeer H, Kemp AH, Fisher Z. The Impact of Psycho-Social Interventions on the Wellbeing of Individuals With Acquired Brain Injury During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021;12:648286. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yakushko O. Scientific Pollyannaism, From Inquisition to Positive Psychology. Published online; 2019. 10.1007/978-3-030-15982-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostry JD, Loungani P, Furceri D. Neoliberalism: Oversold? Finance Dev. 2016;53(2). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker JC, Hartwich L, Haslam SA. Neoliberalism can reduce well‐being by promoting a sense of social disconnection, competition, and loneliness. Br J Soc Psychol. 2021;60(3):947-965. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coyne JC. Positive psychology is mainly for rich white people. 2013. https://www.coyneoftherealm.com/2013/08/21/positive-psychology-is-mainly-for-rich-white-people/ Accessed August 6, 2021.

- 16.Carlisle S, Henderson G, Hanlon PW. 'Wellbeing': A collateral casualty of modernity? Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(10):1556-1560. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, et al. World scientists' warning of a climate emergency 2021. Bioscience. 2021;71:894-898. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biab079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mead J, Fisher Z, Kemp AH. Moving Beyond Disciplinary Silos Towards a Transdisciplinary Model of Wellbeing: An Invited Review. Front Psychol. 2021;12:12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.642093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mead J, Fisher Z, Wilkie L, et al. Rethinking Wellbeing: Toward a More Ethical Science of Wellbeing that Considers Current and Future Generations. Published online; 2019. 10.22541/au.156649190.08734276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antó JM, Martí JL, Casals J, et al. The Planetary Wellbeing Initiative: Pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals in Higher Education. Sustainability. 2021;13(6):3372. doi: 10.3390/su13063372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lomas T, Waters L, Williams P, Oades LG, Kern ML. Third wave positive psychology: broadening towards complexity. J Posit Psychol. 2020;16:660-674. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1805501. Published online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong PTP, Arslan G, Bowers VL, et al. Self-Transcendence as a Buffer Against COVID-19 Suffering: The Development and Validation of the Self-Transcendence Measure-B. Front Psychol. 2021;12:648549. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jetten J, Reicher SD, Haslam SA, Cruwys T, eds Together Apart: The Psychology of COVID-19. New York, NY: Sage Publications Ltd; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson M, Hamlin I. Nature engagement for human and nature's well-being during the Corona pandemic. J Publ Ment Health. 2021;20(2):83-93. doi: 10.1108/jpmh-02-2021-0016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bendell J. Psychological insights on discussing societal disruption and collapse. Ata: Journal of Psychotherapy Aotearoa New Zealand. 2021;25(1):45-63. doi: 10.9791/ajpanz.2021.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waters L, Cameron K, Nelson-Coffey SK, et al. Collective wellbeing and posttraumatic growth during COVID-19: how positive psychology can help families, schools, workplaces and marginalized communities. J Posit Psychol. 2021:1-29. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2021.1940251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corral-Verdugo V, Pato C, Torres-Soto N. Testing a tridimensional model of sustainable behavior: self-care, caring for others, and caring for the planet. Environ Dev Sustain. 2021;23(9):12867-12882. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-01189-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi B and Pak A. Multidisciplinarity, Interdisciplinarity and Transdisciplinarity in Health Research, Services, Education and Policy: 1. Definitions, Objectives, and Evidence of effectiveness. Clin Invest Med 2006;29(6):351-364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen TW, Ma JS. Connecting Social and Natural Ecologies Through a Curriculum of Giving for Student Wellbeing and Engagement. Aust J Environ Educ. 2018;34(3):215-227. doi: 10.1017/aee.2018.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher Z, Galloghly E, Boglo E, Gracey F, Kemp AH. Emotion, Wellbeing and the Neurological Disorders. In: Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022:220-234. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-819641-0.00013-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Waal Ade, Weaver M, Day T, van der Heijden B. Silo-Busting: Overcoming the Greatest Threat to Organizational Performance. Sustainability. 2019;11(23):6860. doi: 10.3390/su11236860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carr A, Cullen K, Keeney C, et al. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2020;16:749-769. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807. Published online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buecker S, Simacek T, Ingwersen B, Terwiel S, Simonsmeier BA. Physical activity and subjective well-being in healthy individuals: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2020;15:574-592. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2020.1760728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haslam C, Jetten J, Cruwys T, Dingle G, Haslam A. The New Psychology of Health: Unlocking the Social Cure. New York, NY: Routledge; 2017. https://www.routledge.com/The-New-Psychology-of-Health-Unlocking-the-Social-Cure/Haslam-Jetten-Cruwys-Dingle-Haslam/p/book/9781138123885. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corral-Verdugo V. Psychology of climate change (Psicología del cambio climático). Psyecology. 2021;12(2):254-282. doi: 10.1080/21711976.2021.1901188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haig BD. An Abductive Theory of Scientific Method. Psychol Methods. 2005;10(4):371-388. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.10.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Żelechowska D, Żyluk N, Urbański M. Find out a new method to study abductive reasoning in empirical research. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:160940692090967. doi: 10.1177/1609406920909674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, Duffy ME, Binau SG. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128(3):185-199. doi: 10.1037/abn0000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheldon E, Simmonds-Buckley M, Bone C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in university undergraduate students: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;287:282-292. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim GY, Tam WW, Lu Y, Ho CS, Zhang MW, Ho RC. Prevalence of Depression in the Community from 30 Countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kemp AH, Mead J, Sandhu S, Fisher Z. Teaching Wellbeing Science. Open Science Framework. Published online; 2021. doi: 10.17605/osf.io/e7zjf. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kemp AH, Fisher Z. Application of single-case research designs in undergraduate student reports: an example from wellbeing science. Teaching of Psychology. 2021:009862832110299. Published online 2021. doi: 10.1177/00986283211029929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheldon KM, Lyubomirsky S. Revisiting the Sustainable Happiness Model and Pie Chart: Can Happiness Be Successfully Pursued? J Posit Psychol. 2019;16:145-154. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2019.1689421.Published online [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Brien C. Education for Sustainable Happiness and Well-Being. New York, NY: Routledge. Published online; 2016. doi: 10.4324/9781315630946. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weziak-Bialowolska D, Bialowolski P, VanderWeele TJ, McNeely E. Character strengths involving an orientation to promote good can help your health and well-being. evidence from two longitudinal studies. Am J Health Promot. 2020;35;388-398. doi: 10.1177/0890117120964083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Djernis L, Lerstrup S, Poulsen O’T, Stigsdotter fnm, Dahlgaard fnm, O’Toole fnm. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nature-based mindfulness: effects of moving mindfulness training into an outdoor natural setting. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2019;16(17):3202. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16173202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mead JP, Fisher Z, Tree JJ, Wong PTP, Kemp AH. Protectors of wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: key roles for gratitude and tragic optimism in a UK-based cohort. Front Psychol. 2021;12:647951. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burgmer P, Forstmann M. Mind-Body Dualism and Health Revisited. Soc Psychol. 2018;49(4):219-230. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahar C, Fraser K. Barriers to successful community reintegration following acquired brain injury (ABI). Int J Disabil Manag. 2011;6(1):49-67. doi: 10.1375/jdmr.6.1.49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martin L, White MP, Hunt A, Richardson M, Pahl S, Burt J. Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours. J Environ Psychol. 2020;68:101389. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fabian M, Pykett J. Be happy: navigating normative issues in behavioral and well-being public policy. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2021:174569162098439. doi: 10.1177/1745691620984395. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]