Abstract

A newly developed nested PCR assay was applied to murine models of histoplasmosis. ICR and BALB/c mice were intravenously infected with Histoplasma capsulatum and sacrificed up to 29 days later. Samples of blood, spleen, and lung homogenates were cultured and examined by the PCR assay. In the ICR mouse model, 265 of 319 organ samples showed concordant results. With 7 samples, the culture was positive and the PCR assay was negative whereas a positive PCR but a negative culture were obtained with 47 samples (P < 0.0001 according to McNemar's test). Organ homogenates and blood samples of either spontaneously cured or treated BALB/c mice were PCR negative. The nested PCR assay performs excellently in the monitoring of spontaneously and treatment-cured murine histoplasmosis. It limits the infection risks of the laboratory staff and might be of diagnostic value for humans.

Histoplasmosis is mainly diagnosed by culture and antigen detection in clinical specimens. Since the culture of the etiological agent, Histoplasma capsulatum, requires a biosafety level III laboratory and the antigen assay is currently performed in only one laboratory (9), diagnosis is restricted. Studies of potentially effective new drugs with animal models are limited by the hazardousness of the pathogen and the risk of laboratory infection. PCR assays have been proposed for the diagnosis of invasive fungal disease because of their higher sensitivity and the reduction in the time until diagnosis compared to culture (2–4, 10).

In this study, a new nested PCR assay was developed. It was applied to murine models of histoplasmosis and compared to quantitative cultures.

(The data presented here are parts of the doctoral theses of Jörg Fischer and Antje Feucht.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Forty Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice were infected intravenously with a sublethal inoculum of 8 × 103 yeast phase cells of H. capsulatum (strain 93/255; M. G. Rinaldi, Fungus Testing Laboratory, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio). On days 1, 5, 11, 15, and 29 postinfection (p.i.), eight mice were sacrificed. EDTA-blood was obtained by cardiac puncture, and organs were removed under aseptic conditions. Two times, 100 μl of EDTA-blood was plated on blood agar. The right lung and a part of the spleen were weighed, placed in 2 ml of saline, and homogenized. The tissue homogenates were serially diluted 10-fold, and 2 × 100 μl of each dilution was plated on blood agar. After 5 to 7 days of incubation at 37°C, the CFU were counted and the concentration per gram of tissue or milliliter of blood was calculated. The remaining tissue homogenates, dilutions, and EDTA-blood were stored frozen (−20°C) until DNA extraction was done.

Immunocompetent BALB/c nu/+ mice were infected intravenously with a lethal inoculum of 2.5 × 107 CFU of H. capsulatum. Twenty-four mice were given liposomal amphotericin B (10 mg/kg from day 2 until day 12 p.i.), whereas another 24 remained untreated. Six mice in each group were sacrificed on days 1, 15, 22, and 29 p.i. EDTA-blood was taken by cardiac puncture, 2 × 100 μl was plated on blood agar, and the number of CFU per milliliter was calculated as described above. The remaining blood was stored frozen (−20°C) until DNA extraction was done.

The studies followed the U.S. Public Health Service Policy on the Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the U.S. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

DNA extraction.

The organ homogenates and dilutions were thawed, and 200 μl of each sample was used for extraction of DNA; 180 μl of ATL buffer from the QIAamp tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and proteinase K (Qiagen) to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml were added. After incubation at 55°C for at least 2 h or overnight, the samples were boiled for 5 min and then exposed to three cycles of freezing in liquid nitrogen for 1 min and boiling for 5 min to disrupt the fungal cells. After cooling to room temperature, proteinase K (Qiagen) was added again to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. After incubation at 55°C for 1 h, DNA was extracted using the QIAamp tissue kit (Qiagen) based on binding of the DNA to silica columns, following the manufacturer's instructions.

After thawing and vortexing of the samples, 100 μl of EDTA-blood was incubated with 400 μl of red cell lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM sodium chloride) for 10 min at room temperature under constant shaking. After centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 5 min, the supernatant was removed and 500 μl of lysis buffer was added to the pellet. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 min and centrifuged, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was used for DNA extraction as described above.

Primer design.

The sequence of the small-subunit (18S) rRNA gene of H. capsulatum in the GenBank database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (accession number X58572) was screened for primers. The outer primer set fungus I (5′-GTT AAA AAG CTC GTA GTT G-3′) and fungus II (5′-TCC CTA GTC GGC ATA GTT TA-3′) is complementary to a highly conserved region, amplifying a 429-bp sequence of several fungi pathogenic for humans. The inner primer set histo I (5′-GCC GGA CCT TTC CTC CTG GGG AGC-3′) and histo II (5′-CAA GAA TTT CAC CTC TGA CAG CCG A-3′), being complementary to positions 643 to 666 and 873 to 849 of the small-subunit rDNA, respectively, delimits a specific 231-nucleotide sequence.

PCR assay.

The reaction mixture of the first PCR consisted of 10 μl of DNA extract in a total volume of 50 μl with final concentrations of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, and 2.5 mM MgCl2 (10× Perkin-Elmer buffer II plus MgCl2 solution [Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, N.J.]); a 1-μM concentration of each primer (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany); 1.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer); and a 100-μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Promega, Madison, Wis.). The reaction mixture of the second PCR was identical, except that 1 μl of the first reaction mixture, a 50-μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and a 1-μM concentration of each primer of the inner primer set were used. Reaction mixtures with the outer primer set were thermally cycled once at 94°C for 5 min, 35 times at 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and then once at 72°C for 5 min. For the nested PCR product, reaction mixtures were thermally cycled once at 94°C for 5 min, 30 times at 94°C for 30 s and 72°C for 1 min, and then once at 72°C for 5 min. The high melting temperatures of the inner primers allowed a two-step nested PCR with high stringency. The PCR was run in a Primus PCR thermocycler Tc 9600 (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized on a UV transilluminator.

Detection limit.

H. capsulatum suspensions with the yeast cell concentration defined by quantitative culture were used for DNA extraction and the nested PCR assay. The minimal CFU count per sample resulting in a positive PCR assay result was then determined.

Controls.

Ten microliters of DNA extract of an H. capsulatum suspension (1,000 CFU/ml) was used in every PCR assay as a positive control. Sterile water was included in the DNA extraction and was used as a negative control after every 10th sample in the nested PCR assay to monitor for crossover contamination. A reaction mixture without DNA was run in the first and second cycles to detect contamination.

DNA extraction was controlled by a PCR using the primer set actin 4 (5′-AGC CAT GTA CGT AGC CAT CCA GGC T-3′) and actin 5 (5′-GGA TGT CAA CGT CAC ACT TCA TGA TGG-3′), amplifying a 450-bp sequence of the mouse actin gene and thus indicating the presence of amplifiable murine DNA. The reaction mixture was identical to the mixture described above, except that 3 mM MgCl2, a 1-μM concentration of each primer, and only 5 μl of the DNA extract were used. The reaction mixture was thermally cycled according to the first PCR protocol described above, except that an annealing temperature of 57°C was used.

Sequencing.

The nested PCR products were purified by using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen), based on DNA binding to a silica membrane. Automated sequencing was done with the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit and PCR primers in accordance with the recommendations of the manufacturer, and the sequence was analyzed on an ABI 373 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems Division, Perkin-Elmer Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Sequences were generated from both strands, edited and aligned with the Sequence Navigator software (Applied Biosystems), and used for a BLAST search of the GenBank database (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Washington, D.C.).

Statistics.

In order to describe the probability of a positive culture or PCR result as a function of the fungal concentration, a three-parameter logistic model with a potentially positive background level was fitted by maximum likelihood and compared to the observed proportions and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

RESULTS

CFU counts in ICR mice.

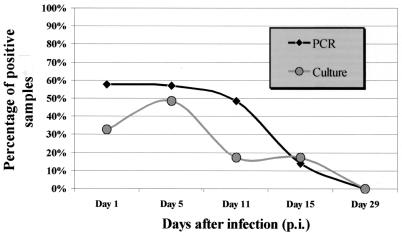

On day 1 p.i., we found 1 to 8 CFU of H. capsulatum mg of spleen−1. The tissue burden peaked on day 5 with 100 to 700 CFU mg of spleen−1 and declined thereafter. All spleen samples from day 29 p.i. were culture negative (Fig. 1). The fungal burden of the lungs showed a similar curve, but with lower numbers of yeast cells and completely negative cultures already from day 15 p.i. on. All 40 blood samples were sterile; i.e., no colony of H. capsulatum was grown. Two uninfected mice were kept in a cage next to the infected animals. They were sacrificed on day 29, and all cultures of organs and blood were H. capsulatum negative.

FIG. 1.

H. capsulatum tissue burdens of lungs and spleens detected by PCR and culture. On each day p.i., 64 samples, except on day 5 p.i. (only 63 samples) from eight ICR mice were examined.

H. capsulatum nested PCR.

By using defined H. capsulatum cell suspensions, the detection limit of the nested PCR assay was five yeast cells per volume to be extracted. Since four dilutions of each lung and spleen homogenate were examined but one sample broke, a total of 319 ICR mouse samples were examined by the nested PCR assay. As shown in Table 1, the results for 265 (83.1%) of these were concordant for both assays, i.e., either positive or negative by both PCR assay and culture. Discordant results were seen in 54 (16.9%) samples, of which 7 (2.2%) were positive by culture but negative by the PCR assay, whereas 47 (14.7%) were culture negative but PCR positive. All 16 organ samples of the two uninfected ICR mice were PCR negative.

TABLE 1.

Results of PCR assays and cultures of tissue samples from H. capsulatum-infected ICR mice

| Organ and Culture result | No. of PCR results

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Spleen | |||

| Positive | 46 | 7 | 53 |

| Negative | 25 | 81 | 106 |

| Total | 71 | 88 | 159 |

| Lung | |||

| Positive | 20 | 0 | 20 |

| Negative | 22 | 118 | 140 |

| Total | 42 | 118 | 160 |

| All tissue samples | |||

| Positive | 66 | 7 | 73 |

| Negative | 47 | 199 | 246 |

| Total | 113 | 206 | 319 |

Controls.

For 308 (96.5%) of 319 samples, the mouse actin PCR assay results were positive, indicating the presence of amplifiable mouse DNA. For eleven samples of the 1:1,000 dilutions, the actin PCR assay was negative due to the insufficient amount of extracted mouse DNA. For all samples of the two control mice, the actin PCR assay results were positive.

Comparison of PCR and culture.

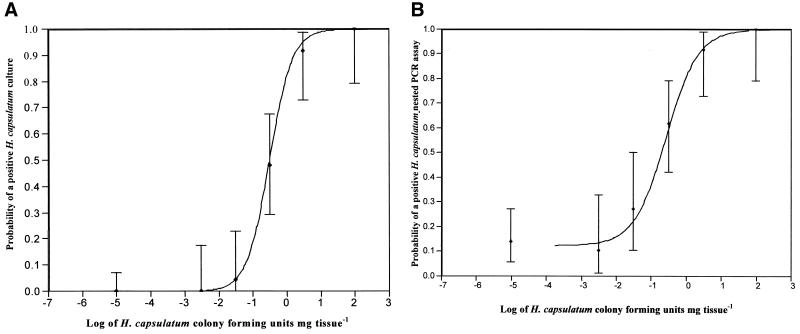

The course of infection, characterized by the percentage of samples positive by culture and PCR at each day p.i., is shown in Fig. 1. In order to compare PCR assay and culture results, a model was calculated. The probability that a positive result would be obtained by each method was calculated as a function of the log concentration of CFU of H. capsulatum per milligram of organ. The spleen sample results are shown in Fig. 2. Whereas a concentration of 0.1 CFU mg of spleen−1 has a 33% probability to be positive by the nested PCR assay, culture will be positive with less than 10% of the samples. This difference is highly significant (P < 0.0001), indicating that the PCR assay is three times more sensitive than detection of fungi by culture. The results obtained with lung samples were comparable, showing that the PCR assay is 17 times more sensitive than culture (P < 0.0001; data not shown).

FIG. 2.

(a) Probability of a positive H. capsulatum culture result, depending on the fungal concentration in spleen tissue of infected ICR mice. Vertical bars, 95% CI and observed proportion of a positive culture result; curve, expected probability of a positive culture. Point of inflection log concentration = −0.49 (95% CI, −0.71 to −0.27); slope parameter, 3.0 (95% CI, 2.0 to 4.4). (b) Probability of a positive H. capsulatum nested PCR assay result, depending on the fungal concentration in spleen tissue of infected ICR mice. Vertical bars, 95% CI and observed proportion of a positive nested PCR assay result; curve, expected probability of a positive nested PCR assay result. Point of inflection log concentration = −0.57 (95% CI, −0.88 to −0.27); slope parameter, 2.2 (95% CI, 1.4 to 3.5); asymptote for very low concentrations, 0.125 (95% CI, 0.066 to 0.201).

Sequencing.

One nested PCR product of each animal that was positive in at least one dilution was sequenced for further identification. Each of the 29 sequences was 100% identical to the sequence of the H. capsulatum strain used in this study and 99% homologous to the 18S rRNA gene sequence in the GenBank database (accession number X58572).

BALB/c nu/+ mice.

H. capsulatum could be grown from 10 of 12 blood samples from untreated mice (10 to 170 [median, 20] CFU of H. capsulatum ml of blood−1) on days 1 and 15 p.i., and all samples were positive by the PCR assay. Cultures of the 12 blood samples collected on days 22 and 29 were sterile and negative by the PCR assay. H. capsulatum was cultured from five of six blood samples from amphotericin B-treated mice on day 1 p.i. (10 to 140 [median, 50] CFU of H. capsulatum ml of blood−1). All of the cultures, a total of 18, were sterile on days 15, 22, and 29 p.i. In the nested PCR assay, all six blood samples of the first day were positive and all 18 samples were negative thereafter.

Amplifiable mouse DNA was demonstrated in all DNA extracts from blood samples by a positive actin PCR assay result. All PCR-negative samples turned positive after addition of 2 μl of the positive control excluding inhibitors. Thus, the sensitivity and specificity of the PCR assay shown with organ homogenates of ICR mice could be demonstrated as well in blood samples from BALB/c nu/+ mice.

DISCUSSION

A nested PCR assay for the detection of H. capsulatum DNA in infected animal tissue and blood samples was established. Compared to quantitative culture on blood agar, this assay was highly significantly more sensitive. Discordant results were found at concentrations of 0.2 to 1.7 CFU/mg of organ, which is equivalent to 1 to 11 CFU/volume to be extracted or screened by culture. Despite its higher sensitivity, the PCR assay turns negative after the mice are cured either spontaneously or by treatment (Fig. 1). Thus, the PCR assay result correlates favorably with the presence of viable fungal cells and H. capsulatum-specific DNA persists neither in infected organs nor in the circulating blood.

Culture of the yeast phase of H. capsulatum on blood agar has been used as the standard procedure to measure the tissue burden in murine histoplasmosis. Comparison of culture and hemocytometer counts had demonstrated a recovery rate of 80%. This might explain the different sensitivities, and a highly enriched medium might have increased the yield of fungal cells. However, the established standard procedure in the laboratory was used to evaluate our new PCR assay.

In order to test new PCR assays for invasive fungal disease, studies have been done with animal models, mainly for aspergillosis and candidiasis (2–5, 7, 8, 10). All of the authors concluded that the PCR assay was “globally” more sensitive than culture, but none gave statistical evidence supporting their conclusions. The mathematical model of the probability of a positive assay allowed a comparison of the two applied methods. The higher sensitivity of the nested PCR assay described herein was proven statistically. The goodness of fit of the model was demonstrated by the fact that the CIs of the data contained the expected values predicted by the model.

Recently, Reid and Schafer described a nested PCR assay for the detection of H. capsulatum in soil samples using the internal transcribed spacer region as the target sequence (6). The 5-cell H. capsulatum detection limit of our PCR assay is in accordance with that of 10 fungal cells per sample to be examined reported by them.

The newly developed nested PCR assay is able to monitor the natural course of murine histoplasmosis as well as therapeutic effects, and it limits the risk of laboratory infection. Its efficiency in the monitoring of human infection remains to be determined. It might be used as a screening assay for dimorphic fungal disease in general, because preliminary data show that this nested PCR assay can detect DNA of the closely related fungi Blastomyces dermatitidis and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis as well (1).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Sanitätsrat-Dr.-Emil-Alexander-Huebner-und-Gemahlin-Stiftung, Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft, Essen, and by a grant from the Universitätsklinikum Tübingen (fortüne 530).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bialek R, Ibricevic A, Fothergill A, Begerow D. Small subunit ribosomal DNA sequence shows Paracoccidioides brasiliensis closely related to Blastomyces dermatitidis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3190–3193. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3190-3193.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kan V L. Polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of candidemia. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:779–783. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.3.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makimura K, Murayama S Y, Yamaguchi H. Detection of a wide range of medically important fungi by polymerase chain reaction. J Med Microbiol. 1994;40:358–364. doi: 10.1099/00222615-40-5-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melchers W J G, Verweij P E, van den Hurk P, van Belkum A, de Pauw B E, Hoogkamp-Korstanje J A A, Meis J F G M. General primer-mediated PCR for detection of Aspergillus species. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1710–1717. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1710-1717.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polanco A, Mellado E, Castillo C, Rodriguez-Tuleda J L. Detection of Candida albicans in blood by PCR in a rabbit animal model of disseminated candidiasis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;34:177–183. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(99)00036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid T M, Schafer M P. Direct detection of Histoplasma capsulatum in soil suspensions by two-stage PCR. Mol Cell Probes. 1999;13:269–273. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1999.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Deventer A J M, Goessens W H F, van Belkum A, van Etten E W M, van Vliet H J A, Verbrugh H A. PCR monitoring of response to liposomal amphotericin B treatment of systemic candidiasis in neutropenic mice. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:25–28. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.25-28.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Deventer A J M, Goessens W H F, van Belkum A, van Vliet H J A, van Etten E W M, Verbrugh H A. Improved detection of Candida albicans by PCR in blood of neutropenic mice with systemic candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:625–628. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.625-628.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wheat L J, Kohler R B, Tewari R P. Diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis by detection of Histoplasma capsulatum antigen in serum and urine specimens. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:83–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601093140205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamakami Y, Hashimoto A, Tokimatsu I, Nasu M. PCR detection of DNA specific Aspergillus species in serum of patients with invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2464–2468. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2464-2468.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]