Abstract

An array of human cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), overexpress the oncogene Astrocyte elevated gene-1 (AEG-1). It is now firmly established that AEG-1 is a key driver of carcinogenesis, and enhanced expression of AEG-1 is a marker of poor prognosis in cancer patients. In-depth studies have revealed that AEG-1 positively regulates different hallmarks of HCC progression including growth and proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, migration, metastasis and resistance to therapeutic intervention. By interacting with a plethora of proteins as well as mRNAs, AEG-1 regulates gene expression at transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and translational levels, and modulates numerous pro-tumorigenic and tumor-suppressive signal transduction pathways. Even though extensive research over the last two decades using various in vitro and in vivo models has established the pivotal role of AEG-1 in HCC, effective targeting of AEG-1 as a therapeutic intervention for HCC is yet to be achieved in the clinic. Targeted delivery of AEG-1 small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA) has demonstrated desired therapeutic effects in mouse models of HCC. Peptidomimetic inhibitors based on protein-protein interaction studies has also been developed recently. Continuous unraveling of novel mechanisms in the regulation of HCC by AEG-1 will generate valuable knowledge facilitating development of specific AEG-1 inhibitory strategies. The present review describes the current status of AEG-1 in HCC gleaned from patient-focused and bench-top studies as well as transgenic and knockout mouse models. We also address the challenges that need to be overcome and discuss future perspectives on this exciting molecule to transform it from bench to bedside.

1. Introduction

Liver cancer is the fourth most lethal tumor globally with a 5-year survival of 18% (Bray et al., 2018; Villanueva, 2019). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), arising from primary hepatocytes, constitutes over 80% of all liver cancers (El-Serag, 2011; Robertson, Srivastava, Rajasekaran, et al., 2015). HCC is generally a consequence of chronic liver disease in which there is injury and inflammation to the liver for decades leading to hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis and ultimately HCC. The majority of HCC cases develop owing to viral hepatitis, and globally, Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are considered as the most significant HCC risk factors (Dimitroulis et al., 2017; Donato, Boffetta, & Puoti, 1998; Sarkar, 2013). Heavy alcohol consumption for a long time may lead to chronic liver disease and HCC development. The increasing numbers of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), as a consequence of metabolic syndrome and obesity, is currently considered a major risk factor for HCC (Anstee, Reeves, Kotsiliti, Govaere, & Heikenwalder, 2019; Friedman, Neuschwander-Tetri, Rinella, & Sanyal, 2018; Rajesh & Sarkar, 2020; Villanueva, 2019). Contamination of food and medicine may also lead to the development of HCC. For instance, aflatoxins, frequent contaminants of many staple cereals and oil-seeds, may give rise to serious public health jeopardy including the causation of HCC (Kew, 2013). Aristolochic acid (AA), found in traditional Chinese herbal medicines, can also increase the risk of HCC development (Ng et al., 2017). Other factors that can cause HCC are hemochromatosis, smoking, coinfection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with either HBV or HCV, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, autoimmune hepatitis, porphyrias, and Wilson disease (Sarkar, 2013; Villanueva, 2019; Yang et al., 2019).

More than 50% of HCC cases are diagnosed in China; and among those patients, 90% population are infected with HBV. It is expected that the etiologic landscape of HCC might be changed after universal HBV vaccination and a wide range of application of direct-acting antiviral agents against HCV infection. Indeed, HBV vaccination reduces the incidence of HCC (Chang et al., 2009). However, there are still a large number of individuals who remain to be vaccinated, and therefore, they are at risk of developing HCC (Yuen et al., 2018). Antiviral therapies reduce the incidence of HCC although they do not completely eliminate the risk (Liaw et al., 2004). HCC is generally regarded as rare cancer in Western countries, however, the incidence of HCC is rising in Western countries owing to HCV infection, alcohol abuse, and NAFLD. In HCV-infected patients who show a sustained virologic response to the interferon-based treatment schedule, the risk of HCC is decreased from 6.2% to 1.5%, as compared with patients who do not show a response (Morgan et al., 2013). Nevertheless, the increase in incidence and mortality of HCC is projected to continue in the coming decades because of the pandemic of obesity which shows a direct link to HCC by causing NAFLD (Anstee et al., 2019). Indeed, promoting a healthy lifestyle, such as decreased alcohol consumption coupled with diet and exercise facilitating prevention of metabolic syndrome, significantly reduces the risk of HCC development (Forner, Reig, & Bruix, 2018; Li, Park, et al., 2014). Intriguingly, coffee, statins, metformin, and aspirin have been shown to be protective against formation of HCC in various studies conducted around the world (Bravi, Tavani, Bosetti, Boffetta, & La Vecchia, 2017; Sahasrabuddhe et al., 2012; Singh, Singh, Singh, Murad, & Sanchez, 2013; Zhou et al., 2016). Although protective effects of these agents against HCC have not been confirmed yet in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), coffee use is presently recommended by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) 2018 clinical practice guidelines for HCC (European Association for the Study of the Liver, Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu, & European Association for the Study of the Liver, 2018).

Pathologically, HCC is generally a compact tumor with little stroma and a central necrotic core because of hypoxia. Pathological analysis identifies several types of HCC according to macroscopic and microscopic characteristics. Macroscopically, HCC can be classified into three types, nodular, massive, and infiltrative type (Kojiro, 2005). The nodular form is the most common HCC type and is characterized by single or multiple nodular neoplasms that are well-circumscribed. Massive HCCs consist of a large mass that almost completely replaces one of the lobes of the liver. The infiltrative type of HCC is not circumscribed and is characterized by diffuse infiltration of the liver, with potential to infiltrate into the portal or hepatic vein. HCCs can be divided into two types based on their microscopic appearances, such as well-differentiated and poorly differentiated HCCs. In well-differentiated type, HCC cells are like hepatocytes and form trabeculae, cords, and nests, whereas in poorly differentiated type, tumor cells are pleomorphic, anaplastic, and giant (Kojiro, 2005).

The diagnosis of HCC is of great interest to physicians evaluating patients with liver cirrhosis (Talwalkar & Gores, 2004). HCC can be diagnosed with the use of imaging techniques in cirrhotic patients as a result of the vascular shift that occurs during the malignant transformation of hepatocytes (Villanueva, 2019). The vascular shift converts into a characteristic pattern of hyperenhancement in the arterial phase and washout in venous or delayed phases on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). That pattern has a sensitivity between 66% and 82% and a specificity greater than 90% for the diagnosis of HCC in cirrhotic patients having nodules larger than 1cm in diameter. For patients having nodules with an inconclusive pattern on imaging, and for patients without cirrhosis, the diagnosis should depend on biopsy (Roberts et al., 2018; Villanueva, 2019).

Surveillance for HCC aims to decrease disease-related mortality (Ayuso et al., 2018). Biannual ultrasonography of the abdomen is the recommended method for surveillance, with or without measurement of serum levels of HCC marker alpha-fetoprotein. Biannual ultrasonography allows an early diagnosis when effective therapies are feasible (Forner et al., 2018). However, the performance of ultrasound surveillance is problematic in obese patients (Villanueva, 2019). Cirrhotic patients with nodules that are less than 1cm in diameter should undergo ultrasound surveillance every 3 to 4 months and be considered for a return to conventional surveillance if the nodule is stable in size after 12 months (European Association for the Study of the Liver, Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu, & European Association for the Study of the Liver, 2018).

After the diagnosis of HCC, it is important to determine if the tumor has spread, and if so, how far, which is determined by staging of HCC. The staging process helps describe how much cancer is in the body, how serious the cancer is, and how to treat cancer effectively. The majority of HCC patients have concomitant liver complications, especially cirrhosis who markedly compromises liver function, and as such the risk vs. benefit ratio should be carefully determined before the commencement of the treatment schedule. Indeed, the complex ecosystem of HCC calls for a multidisciplinary approach for the management of the disease with expertise in hepatology, surgical procedure, pathology, bioengineering, chemotherapy, oncology, radiology, and specialized nursing. Thus, the application of interdisciplinary science may enhance the survival of HCC patients. For the adequate estimation of the survival of HCC patients, any staging system must quantify the tumor burden as well as the amount of liver dysfunction and performance status. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) algorithm introduced in 1999 is the most widely applied staging system, and this system measured all the components for the adequate estimation of survival of HCC patients (Ayuso et al., 2018; Forner et al., 2018; Llovet, Bru, & Bruix, 1999). Other staging systems do exist, but their application is restricted to certain geographic locations (Villanueva, 2019). The BCLC system is endorsed in clinical practice guidelines and is also applied for the clinical trial design in HCC (European Association for the Study of the Liver, Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu, & European Association for the Study of the Liver, 2018; Marrero et al., 2018). This staging system divides patients to be in one of five stages and recommends treatment suggestions for each stage (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Current treatment recommendations in different stages of HCC. The staging system is based on the BCLC algorithm introduced in 1999. The lenvatinib clinical trial did not include patients with 50% or higher occupation of the liver with tumors or invasion of the bile duct or main portal vein. None of the second-line therapies were tested in patients after lenvatinib therapy.

HCC is a highly aggressive malignancy and hypervascular in nature with rapid growth and early vascular invasion; therefore, the occurrence and loss of life run in parallel in the case of HCC. Clinical management options for HCC patients include surgical resection, tumor ablation with radiofrequency, liver transplantation, transarterial therapies, and systemic therapies. The majority of HCC patients are diagnosed with advanced symptoms that are not manageable by surgical resection or transplantation (Robertson, Srivastava, Rajasekaran, et al., 2015; Villanueva, 2019). For advanced HCC, multi-kinase inhibitor sorafenib has been the treatment of choice for more than a decade and recently other tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as lenvatinib, regorafenib, and cabozantinib, and ramucirumab, a monoclonal antibody blocking VEGF2R signaling, have been approved either as first line therapy or following sorafenib treatment (Abou-Alfa et al., 2018; Bruix et al., 2017; Kudo et al., 2018; Llovet et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2019). In recent years, immunotherapy has come into limelight as a promising approach for HCC which includes immune checkpoint blockers/monoclonal antibodies against the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), PD-1 ligand (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, MED14736, ipilimumab and tremelimumab (Johnston & Khakoo, 2019). PD-1 inhibitor Nivolumab showed efficacy in ~20% HCC patients of all etiologies with significantly improved survival benefits compared to TKIs and nivolumab and pembrolizumab have been approved for HCC treatment as a second line therapy following sorafenib (El-Khoueiry et al., 2017). Even with existence of HCC biomarkers, such as alpha-fetoprotein and glypican-3 (GPC-3), as well as newly discovered gene signatures, early detection and surveillance are still suboptimal contributing to continuing increase in global incidence and mortality of HCC (Liu et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2019). This scenario is further complicated by the fact that HCC is inherently resistant to conventional chemo- and radiotherapy and approved therapeutics for the treatment of HCC increase the survival of patients for only a few months as compared to placebo. This morbid scenario calls for identification of unique molecules driving HCC development and progression leading to the discovery of novel molecular medicine that can mitigate the suffering of these patients.

2. The molecular biology of HCC

Recent data have identified several molecular abnormalities, including somatic DNA alterations, in HCC. Mutations in various proto-oncogenes, such as insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), CTNNB1 (encoding β-catenin), c-Myc, and cyclin D1, and tumor suppressor genes, such as p53, p73, retinoblastoma (Rb), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), deleted in liver cancer 1 (DLC1), deleted in liver cancer 2 (DLC2), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1), glutathione S-transferase pi 1 (GSTP1), hepatocellular carcinoma suppressor 1 (HCCS1)/VPS53, SMAD family member 2 and 4 (SMAD2/4), and axis inhibition protein 1 (AXIN1), have been identified in HCC (Boyault et al., 2007; Mann et al., 2007; Teufel et al., 2007). A plethora of non-coding RNAs, including miRNA and long non-coding RNAs, has been implicated in HCC pathogenesis (Manna & Sarkar, 2020). Comprehensive studies combining exome sequencing, transcriptome analysis, and genomic characterization of HCCs have shown that HCC is heterogeneous at the molecular level (Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Electronic address: wheeler@bcm.edu, & Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2017; Hoshida et al., 2009; Schulze et al., 2015). One validated analysis has identified six robust sub-groups of HCC, designated G1–G6, that have characteristic genetic and clinical features (Amaddeo et al., 2015; Boyault et al., 2007). Mutations in the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter (occurring ~60% of patients with HCC), CTNNB1 (27–40%) and p53 (21–31%,) genes in HCC are the most common (Calderaro et al., 2017; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Electronic address: wheeler@bcm.edu, & Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2017). Specific etiologies of HCC are associated with particular genetic alterations (Calderaro et al., 2017). For instance, TERT promoter and p53 mutations are the most frequent genetic events in HBV-associated HCC, whereas CTNNB1 mutations are strongly associated with alcohol-related HCC. Besides, p53 mutations are linked with decreased survival (Amaddeo et al., 2015; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Electronic address: wheeler@bcm.edu, & Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2017). IL-6/Janus kinase (JNK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway activation without TERT, CTNNB1, or pP53 pathway alterations is frequently seen in the steatohepatitic subtype of HCC (Calderaro et al., 2017). These integrated analyses indicate the molecular diversity of HCC, and different etiologies with distinct mechanisms are involved in hepatocarcinogenesis.

Next-generation sequencing studies in HCC patients treated with systemic therapies are beginning to provide insights into the various cell signaling pathways and the disease control processes in response to specific classes of systemic therapies. For instance, in HCC patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, activating mutations in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway have been linked with a lower disease control rate and survival (Harding et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019). Several abnormal signaling pathways play important role in liver carcinogenesis, and these aberrant signals may provide a source of novel molecular targets for effective therapies. The major signaling cascades activated in HCC are (A) MAPK/ERK pathway, (B) PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, (C) NF-κB pathway, and (D) Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

3. A brief history of AEG-1

It has been almost two decades since the publication of the first discovery and cloning of AEG-1 (Su et al., 2002). AEG-1 was identified as an HIV- and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-inducible gene in primary human fetal astrocytes (PHFAs) with the protein primarily localizing at endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Kang et al., 2005; Su et al., 2002). Since then, a comprehensive body of data on AEG-1 has elucidated diverse functional aspects of this molecule, ranging from its role in cancer biology to fundamental biological processes, such as inflammation and lipid metabolism, and the molecular mechanisms by which it exerts these functions. Initially, in vivo studies confirmed that as a cell membrane protein AEG-1 facilitates metastasis of breast cancer cells to the lung and was named metadherin, and the GenBank symbol for AEG-1 is MTDH (which stands for metadherin), for its participation in tumor metastasis and adhesion (Brown & Ruoslahti, 2004). Rodent (e.g., rat/mouse) AEG-1 was also cloned subsequently as an ER/nuclear envelop protein and as a tight junction protein, and was named lysine-rich CEACAM-1 co-isolated protein (LYRIC) (Britt et al., 2004; Sutherland, Lam, Briers, Lamond, & Bickmore, 2004). It was documented that AEG-1 is overexpressed in different cancer cell lines, such as melanoma, breast cancer and malignant glioma, compared to their normal counterparts (Kang et al., 2005). Indeed, a large set of studies currently indicates that AEG-1 is overexpressed in all types of cancers analyzed to date and it is an essential component critical to the onset and progression of cancer (Emdad et al., 2016; Sarkar & Fisher, 2013; Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2011). AEG-1 expression positively correlates with tumor progression, especially in the metastatic stage, and in vivo studies using nude mice and metastatic models with various cancer cell lines and transgenic and knockout mouse models point out that AEG-1 overexpression induces an aggressive, angiogenic, and metastatic phenotype, and AEG-1 knockdown or knockout markedly hampers tumor initiation, growth, and metastasis (Emdad et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2014; Robertson et al., 2014; Robertson et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2020; Wan, Hu, et al., 2014; Wan, Lu, et al., 2014; Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009).

4. Localization and sequence motifs of AEG-1

The initial discovery of AEG-1 led to an array of research on its biological functions and biochemical characteristics, and although there are still some disputed issues, a number of features of AEG-1 have been agreed upon with unequivocal consensus. AEG-1 gene is located on human chromosome 8q22 and contains 12 exons and 11 introns. In humans, AEG-1 is a lysine-rich highly basic protein having 582 amino acid (a.a.) residues, and the a.a. sequences are highly conserved among vertebrates (Emdad et al., 2007; Kang et al., 2005; Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2011). The three-dimensional structure of full AEG-1 protein has not been elucidated and as such the functional domains of this protein have not been precisely defined, although the structure of the region of AEG-1 with which it interacts with staphylococcal nuclease and tudor domain containing 1 (SND1) has been resolved (Guo et al., 2014). Intracellular localization of AEG-1 has been studied extensively to understand its biological functions showing variable results. It seems that the localization of AEG-1 in cells depends on the cell type examined and the imaging techniques employed. In various experimental procedures, AEG-1 can be detectable in the cytoplasm/ER as well as in the nucleus by immunohistochemical (IHC) and immunofluorescent (IF) staining of cultured cells or sectioned specimens of tissue samples (Emdad et al., 2006; Emdad et al., 2007; Kang et al., 2005; Li et al., 2008; Sutherland et al., 2004). Additionally, AEG-1 can be found on the cell membrane in rat liver as well as in mouse breast cancer cells (Britt et al., 2004; Brown & Ruoslahti, 2004), and in contrast to that, a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-fused AEG-1 shows a stronger signal in the nucleus and nucleolus (Thirkettle, Girling, et al., 2009; Thirkettle, Mills, Whitaker, & Neal, 2009).

These apparently discrepant findings can be explained by unique sequence motifs present in AEG-1 (Fig. 2). AEG-1 has a transmembrane domain (TMD) between 50 and 77 a.a. residues which allows it to anchor on ER membrane, the predominant site of its localization, as well as on cell membrane, which is mainly found in aggressive, metastatic cells (Alexia et al., 2013; Brown & Ruoslahti, 2004; Hsu, Reid, Hoffman, Sarkar, & Nicchitta, 2018; Kang et al., 2005). Three nuclear localization sequences (NLS) are present in the lysine-rich regions of AEG-1 between 79 and 91, 432–451 and 561–580 a.a. residues (Emdad et al., 2007; Sutherland et al., 2004; Thirkettle, Girling, et al., 2009). By utilizing the GFP-fusion system, NLS 1 and 3 and their flanking regions were determined to be able to target AEG-1 to nucleus and nucleolus (Thirkettle, Girling, et al., 2009). In benign human tissues, including prostate, thyroid and lung, as well as in primary mouse hepatocytes, AEG-1 is predominantly located in the nucleus, while in cancer cells and tissues it is located mainly in the cytoplasm (Srivastava et al., 2014; Thirkettle, Girling, et al., 2009). It has been suggested that nuclear AEG-1 is a sumoylated protein that undergoes mono-ubiquitination in its NLS2 motif facilitating its translocation out of the nucleus and increased stability in the cytoplasm (Srivastava et al., 2014; Thirkettle, Girling, et al., 2009). In a later study, it was documented that K486 and K491 of AEG-1, which lie in the extended NLS2 region, undergo mono-ubiquitination, and an E3 ubiquitin ligase, TOPORS, was implicated to mediate this reaction (Luxton et al., 2014). This post-translational modification might explain why AEG-1 of predicted 64kD molecular weight shows bands between 70 and 80kD when detected by antibodies raised against various AEG-1 immunogenic fragments. Nonetheless, the biological significance of post-translational modification of AEG-1 in normal body function as well as in the pathophysiology of various diseases including HCC remains to be elucidated. On the other hand, it has also been shown that when stimulated by TNFα AEG-1 translocates to the nucleus from the cytoplasm interacting with p65 subunit of NF-κB and CREB-binding protein (CBP) thereby augmenting NF-κB transcriptional activity (Emdad et al., 2006; Sarkar et al., 2008). Additionally, a number of clinical studies have detected increasing nuclear staining for AEG-1 with progression of cancer, although the significance of this finding has not been studied (Sarkar & Fisher, 2013). Thus, the regulation of AEG-1 localization and the mechanism of its shuttling among different intracellular compartments still requires clarification. Apart from these localization signals, a lung-homing domain has been identified in mouse AEG-1, which corresponds to 381–443 a.a. residues of human AEG-1, facilitating adhesion of breast cancer cells to lung endothelium (Brown & Ruoslahti, 2004; Sarkar et al., 2009). AEG-1 lacks any DNA-binding domains or motifs but it has an LXXLL motif present in its N-terminus (21–25 a.a. residues) with which AEG-1 interacts with the transcription factor retinoid X receptor (RXR) and negatively regulates its activity (Srivastava et al., 2014). The importance of this motif in regulating AEG-1 function will be described in later section.

Fig. 2.

Cartoon showing important structural features of human AEG-1 mediating its function. Please see text for details. TMD: transmembrane domain; NSL: nuclear localization signal; LHD: lung-homing domain. K63-linked polyubiquitin interaction region is required for interaction with upstream ubiquitinated activators of NF-κB, such as RIP1 and TRAF2. Numbers indicate amino acids (a.a.).

5. Mechanism of AEG-1 overexpression in cancer

A plethora of mechanisms contribute to overexpression of AEG-1 in cancer (Fig. 3). Gains and amplifications of chromosome 8q are frequently seen in a variety of cancers, including HCC (Knuutila et al., 1998; Zimonjic, Keck, Thorgeirsson, & Popescu, 1999). Gain of chromosome 8q22, which contains AEG-1 gene, was detected in poor-prognosis breast cancer, and Q-RT-PCR and fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) confirmed AEG-1 gene amplification in breast cancer patients (Hu et al., 2009). Overexpression of AEG-1 is also linked with increased copy numbers of it, primarily due to gains of large regions of chromosome 8q in HCC (Wang et al., 2013; Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). Ha-ras was reported to be upstream of AEG-1, activating PI3K/Akt signaling and increasing binding of c-Myc to key E-box elements in the AEG-1 promoter, thus promoting AEG-1 transcription in transformed astrocytes (Lee, Su, Emdad, Sarkar, & Fisher, 2006). The observation that AEG-1 is under transcriptional control of three potent oncogenic drivers, Ras, Akt and c-Myc, helps explain why AEG-1 plays a pivotal role in cancer development and progression. AEG-1 synergized with Ha-ras to augment soft agar colony formation by immortal melanocytes and AEG-1 siRNA suppressed Ha-ras-mediated colony formation by transformed astrocytes thereby placing AEG-1 as a key nodal point in Ha-ras-mediated oncogenesis (Kang et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2006). Since PI3K/Akt is activated and c-Myc is overexpressed in human HCC, they may also regulate AEG-1 transcription in HCC (Sarkar, 2013). Indeed, c-Myc is also located in chromosome 8q and is co-amplified with AEG-1 in HCC patients, and a transgenic mouse with hepatocyte-specific AEG-1 and c-Myc overexpression developed highly aggressive HCC with lung metastasis demonstrating functional cooperation between these two molecules (Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015). AEG-1 expression is induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNFα, via activation of NF-κB, a mechanism which might contribute to AEG-1 overexpression in cancers generated as a consequence of chronic inflammation, such as HCC (Khuda et al., 2009; Srivastava et al., 2017; Vartak-Sharma, Gelman, Joshi, Borgamann, & Ghorpade, 2014). Post-transcriptionally, AEG-1 is controlled by multiple tumor-suppressor miRNAs, such as miR-375, miR-136, miR-302c, miR-466 and miR-30a-5p, which are downregulated in several cancers, including HCC (He et al., 2012; Jia et al., 2018; Li, Dai, Ou, Zuo, & Liu, 2016; Malayaperumal, Sriramulu, Jothimani, Banerjee, & Pathak, 2020; Zhao et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2014). Several long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been implicated to upregulate AEG-1 by acting as a sponge for specific AEG-1-targeting miRNAs (Han, Fu, Zeng, Yin, & Li, 2020; Lu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2017). In malignant glioma cells, lncRNA human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex P5 (HCP5) promotes malignant phenotype by upregulating Runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) via sponging miR-139, and RUNX1 in turn upregulates AEG-1 transcription by directly binding to its promoter (Teng et al., 2016). LINC01638 interacts with c-Myc protecting it from speckle type BTB/POZ protein (SPOP)-mediated ubiquitination and degradation with subsequent upregulation of AEG-1 and Twist1 promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in triple-negative breast cancer cells (Luo et al., 2018). As mentioned earlier, post-translationally mono-ubiquitination rendered increased stabilization of cytoplasmic AEG-1 in cancer cells (Thirkettle, Girling, et al., 2009). It was documented that cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein 1 (CPEB1) binds to AEG-1 mRNA and increases its translation in glioblastoma cells (Kochanek & Wells, 2013). On the other hand, in HCC cells CPEB3, which functions as a tumor suppressor, binds to 3′-untranslated region of AEG-1 mRNA and inhibits its translation (Zhang et al., 2020). Thus, all potential mechanisms of gene regulation confer AEG-1 overexpression in cancer.

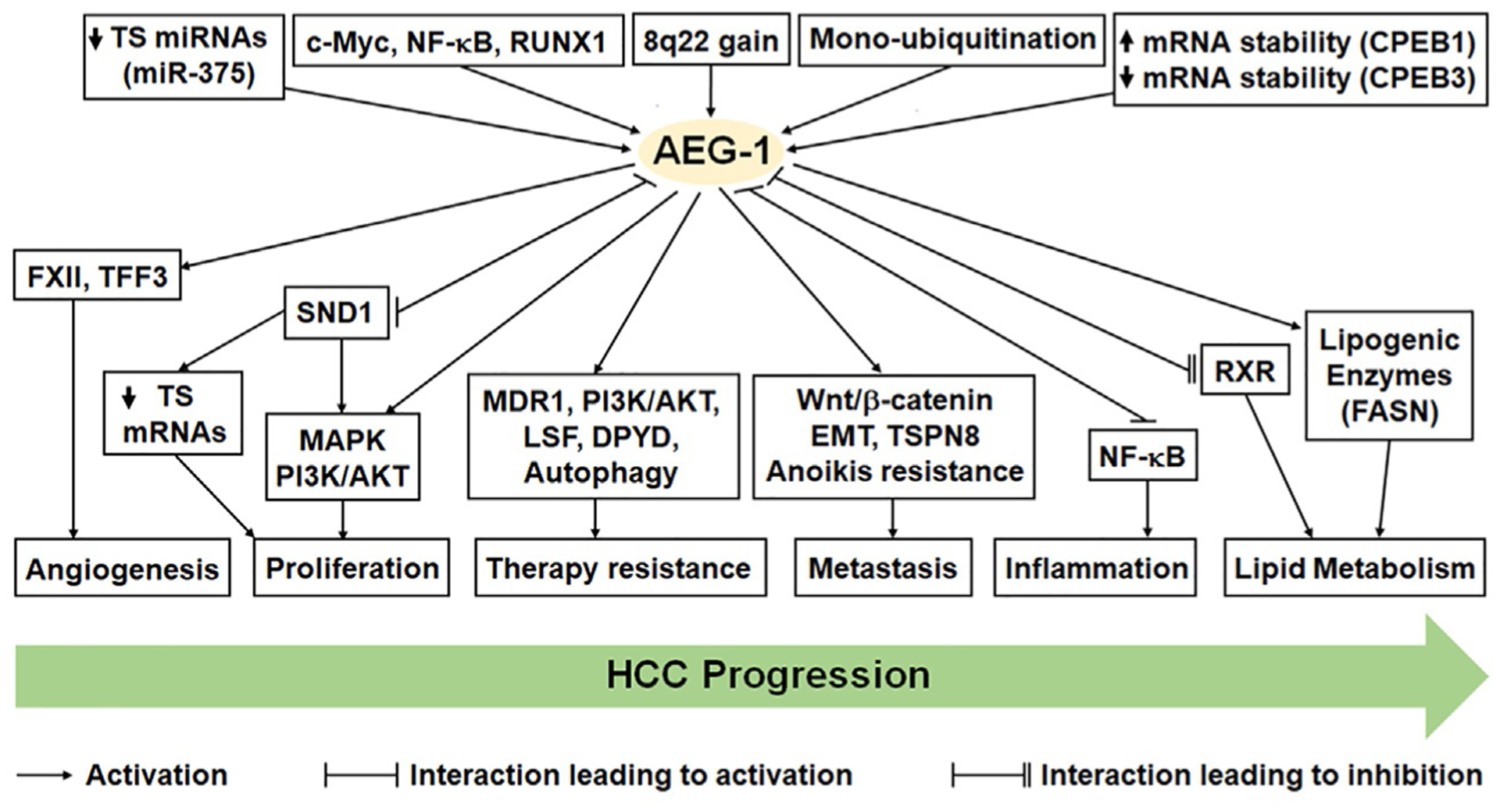

Fig. 3.

Schematic presentation of the mechanisms of AEG-1 regulation and AEG-1 downstream events in HCC. For details, please see the main text.

6. AEG-1: Clinicopathologic findings in HCC

As indicated earlier, AEG-1 functions as an oncogene in all types of cancers, and in this review, we focus on its role in HCC as evidenced from extensive research efforts over the last decade or so. IHC analysis of tissue microarray (TMA) containing 86 primary HCC, 23 metastatic HCC and 9 normal adjacent liver samples showed little to no AEG-1 staining in normal liver samples, while 93.58% of HCC samples showed variable AEG-1 levels which progressively increased with the stages I-IV and from well-differentiated to poorly differentiated (P < 0.0001) (Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). In a separate cohort, including 132 samples in various stages such as normal liver (n = 10), cirrhotic tissue (n = 13), low-grade dysplastic nodules (n = 10), high-grade dysplastic nodules (n = 8), and hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 91), AEG-1 mRNA expression was analyzed from Affymetrix microarray data. In HCV-HCC AEG-1 levels were significantly higher compared to normal and cirrhotic liver with mean up-regulation of 1.7-fold (P = 0.04) and 1.65-fold (P < 0.001), respectively (Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). Genomic amplification of AEG-1 was identified in 26% of HCC patients by DNA copy gain analysis which was also demonstrated in additional studies (Wang et al., 2013; Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009).

Multiple clinicopathologic studies have established AEG-1 as a prognostic marker for HCC. IHC analysis in 323 HCC patients demonstrated AEG-1 expression in 54.2% patients (Zhu et al., 2011). AEG-1 levels were associated with microvascular invasion (P < 0.001), pathologic satellites (P = 0.007), tumor differentiation (P = 0.002), and TNM stage (P = 0.001). The 1-, 3-, 5-year overall survival (OS) in high AEG-1-expressing group were significantly lower than those in low AEG-1-expressing group (83.0% vs. 89.7%, 52.0% vs. 75.3%, 37.4% vs. 66.9%, respectively); and the 1-, 3-, 5-year cumulative recurrence rates were markedly higher in high AEG-1-expressing group than those in low AEG-1-expressing group (32.4% vs. 16.8%, 61.2% vs. 38.2%, 70.7% vs. 47.8%, respectively). AEG-1 was identified as an independent prognostic factor for both OS (HR = 1.870, P < 0.001) and recurrence (HR = 1.695, P < 0.001) by univariate and multivariate analyses (Zhu et al., 2011). Similar univariate and multivariate analyses with Cox regression following IHC of 85 HCC samples revealed that tumor size (HR, 2.285, 95% CI, P = 0.015), microvascular invasion (HR, 6.754, 95% CI, P = 0.008), and AEG-1 expression (HR, 4.756, 95% CI, P = 0.003) were independent prognostic factors for OS, and tumor size (HR, 2.245, 95% CI, P = 0.005) and AEG-1 expression (HR, 1.916, 95% CI, P = 0.038) served as prognostic factors for disease-free survival (DFS) (Jung et al., 2015). The cumulative 5-year survival and recurrence rates were 89.2% and 50.0% in low AEG-1-expressing group and 24.5% and 82.4% in high AEG-1-expressing group, respectively (Jung et al., 2015). A recent study incorporating IHC in HCC TMA, TCGA database analysis and meta-analysis of published data further confirmed the utility of AEG-1 as an HCC prognostic marker (He et al., 2017). AEG-1 has been identified as a prognostic marker for HBV-associated HCC and its levels correlated with the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, 7th edition) stage (P = 0.020), T classification (P = 0.007), N classification (P = 0.044), vascular invasion (P = 0.006) and histological differentiation (P = 0.020) in the HBV-HCC patients (Gong et al., 2012). In addition, patients with high AEG-1 levels had shorter survival times compared to those with low AEG-1 levels (P = 0.001) (Gong et al., 2012).

A known diagnostic marker for HCC is glypican-3 (GPC-3). The diagnostic value of AEG-1 and GPC-3 was analyzed by IHC on HCC, adjacent nontumor tissue (ANT) and dysplastic nodules (DN) (Cao, Sharma, Imam, & Yu, 2019). Compared to ANT and DN, in HCC both AEG-1 and GPC-3 levels were higher showing 92% and 54% positivity, respectively. Alone, AEG-1 showed high sensitivity but low specificity and accuracy, while GPC-3 showed high specificity but low sensitivity and accuracy. However, combination of both augmented the sensitivity, specificity and accuracy to 94.6%, 89.5%, and 90.5%, respectively, suggesting that combined AEG-1 and GPC-3 staining might facilitate early diagnosis of HCC (Cao et al., 2019).

These clinical observations were substantiated in a transgenic mouse with hepatocyte-specific overexpression of AEG-1 (Alb/AEG-1) that generated highly aggressive metastatic HCC in diethylnitrosamine (DEN)-induced HCC model (Srivastava et al., 2012). As a corollary, AEG-1 knockout mice, either total or conditional, were highly resistant to DEN/phenobarbital (PB)-induced hepatocarcinogenesis and metastasis (Robertson et al., 2014, 2018).

In aggressive cancers AEG-1 is detected on the cell membrane giving rise to the hypothesis that autoantibody against AEG-1 might serve as a marker for advanced disease. The lung-homing domain (a.a. 381–443) of human AEG-1 was used as the antigen to detect anti-AEG-1 antibody in sera from 483 different cancer patients, including 98 breast cancer, 96 HCC, 88 colorectal cancer, 51 lung cancer and 88 gastric cancer, by ELISA (Chen et al., 2012). At titers of ≥1:50 anti-AEG-1 antibody was detected in 49% of these patients, including 45% breast cancer, 50% HCC, 49% colorectal cancer, 45% lung cancer and 49% gastric cancer patients, with none of 230 normal individuals displaying positivity (P < 0.01) (Chen et al., 2012). Even though AEG-1 is an established diagnostic/prognostic marker for cancer, its use is limited by the availability of tumor biopsy samples and as such anti-AEG-1 antibody might serve as an important surrogate for AEG-1. However, since the original publication these findings have not been replicated by other studies thereby requiring validation in a large cohort of patients.

7. Cellular signaling affected by AEG-1 in HCC

Interest in the effect of AEG-1 on the malignant phenotype of HCC cells is emerging as a new hotspot of research in the field of cancer biology. As a multifunctional protein, AEG-1 significantly alters a diverse array of signaling networks and effector molecules involved in tumor progression, and HCC is not an exception. In the context of HCC, AEG-1 is a strong activator of multiple pro-tumorigenic signal transduction pathways including NF-κB, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, Wnt/β-catenin, and MAPK/ERK (Fig. 3). However, there is still a need to explore the network of AEG-1 in the complex HCC ecosystem. The present status of downstream mediators of AEG-1 in HCC is discussed below.

7.1. Activation of NF-κB by AEG-1: Promotion of inflammation

Majority of documented risk factors of HCC, such as HBV or HCV infection, alcoholic liver disease and NAFLD, cause long-term liver inflammation and cirrhotic damage leading to HCC (El-Serag, 2011; Forner et al., 2018). Chronic inflammation in HCC is characterized by sustained expression of cytokines and recruitment of various immune cells to the liver. Activated inflammatory cells release free radicals, e.g., reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can cause DNA damage, lead to gene mutations, and ultimately cancer formation (Budhu & Wang, 2006; Karin, 2006; Leonardi et al., 2012). NF-κB is a key transcriptional regulator of the inflammatory response and plays an essential role in regulating inflammatory signaling in the liver (Pikarsky et al., 2004; Taniguchi & Karin, 2018). HCC develops as a consequence of chronic inflammation and as such NF-κB activation is a frequent and early event in human HCC of viral and non-viral etiologies (Hosel et al., 2009; Kim, Lee, & Jung, 2010; Liu et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2010; Tai, Tsai, Chang, et al., 2000; Tai, Tsai, Chen, et al., 2000). Increased levels of LPS, resulting in the activation of NF-κB in the liver, are detected in patients with advanced liver diseases, and fatty acids also activate NF-κB in NAFLD patients (Schwabe, Seki, & Brenner, 2006; Shi et al., 2006). Interestingly, while NF-κB induces AEG-1 expression, the first signaling pathway that was found to be activated by AEG-1 was NF-κB (Emdad et al., 2006; Sarkar et al., 2008). It was documented that upon TNF-α treatment AEG-1 translocates to the nucleus where it interacts with the p65 subunit of NF-κB and CREB-binding protein (CBP) and functions as a bridging factor between NF-κB and basal transcriptional machinery promoting NF-κB-induced transcription (Emdad et al., 2006; Sarkar et al., 2008). Subsequently, it was shown that AEG-1, anchored on ER membrane, associates with upstream ubiquitinated activators of NF-κB, such as RIP1 and TRAF2, facilitating their accumulation and as a consequence NF-κB activation (Alexia et al., 2013). AEG-1 is directly phosphorylated by IKKβ at serine 298 which is essential for IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation (Krishnan et al., 2015). Thus AEG-1 functions in multiple steps in NF-κB activation pathway and as such it is fundamentally required for inflammation which has been clearly demonstrated in AEG-1-deficient mouse models (Robertson et al., 2014, 2018). LPS-induced NF-κB activation is markedly abrogated in AEG-1−/− hepatocytes and macrophages vs. WT (Robertson et al., 2014). While 16-month-old WT mice showed signs of aging-associated inflammation no such changes were observed in AEG-1−/− littermates, and infiltration of macrophages was observed in aged WT liver and spleen but not in AEG-1−/− (Robertson et al., 2014). Indeed, AEG-1−/− mice lived longer than WT littermates and showed profound resistance to DEN-induced activation of oncogenic IL-6/STAT3 signaling and development of HCC (Robertson et al., 2014, 2015). Communication between tumor cells and tumor microenvironment is necessary for HCC development, and it has been shown that NF-κB activation in hepatocytes and macrophages is required for inflammation-induced HCC (Haybaeck et al., 2009; He & Karin, 2011). In a follow-up study it was documented that hepatocyte-specific AEG-1 deficiency (AEG-1ΔHEP) led to only an attenuation (and not complete abrogation), while myeloid-specific AEG-1 deficiency (AEG-1ΔMAC) led to complete abrogation of DEN-induced HCC, indicating that AEG-1 plays a key role in initial macrophage activation that is crucial for hepatocyte transformation (Robertson et al., 2018). AEG-1 deficiency made macrophages anergic so that they did not respond to polarization stimuli and their functional activity was markedly hampered (Robertson et al., 2018). It should be noted that AEG-1-induced inflammation has been attributed to regulate other inflammatory cancers, such as gastric cancer (Li, Wang, et al., 2014). AEG-1 plays a seminal role in contributing to the inflammatory component of NASH, a precursor to HCC, and other inflammatory conditions, such as diabetic kidney disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and HIV-1-associated neuroinflammation (Hong, Wang, & Shi, 2017; Liu et al., 2019; Srivastava et al., 2017; Vartak-Sharma et al., 2014).

7.2. Activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway by AEG-1

Oncogenic Wnt/β-catenin pathway can be activated by multiple mechanisms in HCC, the most common being mutations in CTNNB1 in 30% cases or AXIN1/2 in 5–10% cases (Rebouissou et al., 2016; Satoh et al., 2000). Our endeavors to identify AEG-1-downstream genes by comparing global gene expression between control and AEG-1-overexpressed HCC cells first identified significant modulation of genes belonging to Wnt/β-catenin pathway by AEG-1 (Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). We documented that AEG-1 can activate Wnt/β-catenin pathway by multiple ways: (A) AEG-1 increases expression of lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1), a transcription factor activated by Wnt signaling, and LEF1-regulated genes, such as c-Myc. (B) AEG-1 downregulates expression of negative regulators of the Wnt pathways, like APC and C-terminal-binding protein 2 (CTBP2). (C) AEG-1 activates ERK42/44 which phosphorylates and inactivates glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) resulting in nuclear translocation of β-catenin (Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). Subsequent studies showed that AEG-1 knockdown abrogated nuclear translocation of β-catenin which was associated with decrease in EMT in HCC cells (Zhu et al., 2011). We showed that AEG-1 forms a complex with LEF1 and β-catenin, and AEG-1-mediated activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway facilitated maintenance of glioma stem-like cells and their self-renewal (Hu et al., 2017). Using Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) and mass spectrometry, protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) was identified as an interacting partner of AEG-1, and PRMT5 inhibition abrogated AEG-1-induced increases in proliferation and migration of HCC cells (Zhu, Peng, et al., 2020). It was documented that PRMT5 and β-catenin competitively bind to the same domains of AEG-1, so that AEG-1 can sequester PRMT5 in the cytoplasm, allowing β-catenin to translocate to the nucleus and regulate gene expression (Zhu, Peng, et al., 2020). Altogether, these findings indicate that similar to NF-κB, AEG-1 can also activate Wnt/β-catenin by multiple ways contributing not only to HCC but other cancers as well.

7.3. Activation of PI3K/Akt pathway by AEG-1

Phosphatase and Tensin homolog (PTEN) is a negative regulator of the oncogenic PI3K/Akt pathway and acts by dephosphorylating phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), generated by PI3K. PTEN inactivation, by a variety of mechanisms including loss-of-function mutation and gene deletion, resulting in PI3K/Akt activation, is observed in ~40% HCC patients (Hu et al., 2003). Hepatocyte-specific Pten knockout mouse develops NASH with increase in SREBP-1c and lipogenic genes and eventually HCC (Horie et al., 2004). Conversely, liver-specific Akt2 knockout inhibited hepatic triglyceride (TG) accumulation and a hepatocyte-specific Pik3ca transgenic mouse developed steatosis and HCC (Kudo et al., 2011; Leavens, Easton, Shulman, Previs, & Birnbaum, 2009). While activation of PI3K/Akt pathway induces AEG-1, AEG-1, in turn, activates this pathway which mediates AEG-1-mediated protection from serum starvation-induced apoptosis as well as anoikis resistance in multiple cell types including HCC (Lee et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2014). Mechanistically, it was demonstrated that AEG-1 interacts with Akt2 resulting in prolonged stabilization of Akt S474 phosphorylation and activation of downstream signaling in glioma cells (Hu et al., 2014). Although it remains to be seen whether similar interaction also happens in HCC cells, AEG-1-mediated activation of PI3/Akt signaling has also been demonstrated in Alb/AEG-1 hepatocytes (Srivastava et al., 2012).

7.4. Activation of MAPK/ERK pathway by AEG-1

In most cancers, MAPK pathway is activated by RAS mutations, which, however, are rare in HCC (Yea et al., 2008). Increased phosphorylation of MAPK/ERK and its upstream kinase MAP2K/MEK1/2 has been observed in HCC tissues compared to the adjacent normal liver (Huynh et al., 2003). It is postulated that the main mechanisms underlying MAPK activation in HCC involves ligand overexpression and aberrant epigenetic regulation (Newell et al., 2009). Overexpression of AEG-1 markedly activates MAPK/ERK as well as p38 MAPK and inhibition of either pathway significantly inhibited AEG-1-induced cell proliferation of human HCC cells (Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). Similar finding has also been observed in Alb/AEG-1 hepatocytes with concomitant increased activation of EGFR, an upstream activator of MAPK/ERK signaling (Srivastava et al., 2012; Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015). Proteomic analysis of conditioned media (CM) from WT and Alb/AEG-1 hepatocytes identified upregulation of several components of the complement pathway, most notably Factor XII (FXII) by AEG-1, and knocking down FXII showed decreased activation of EGFR and consequently MAPK/ERK (Srivastava et al., 2012). These observations indicate that ligand overexpression is one mechanism by which AEG-1 activates MAPK/ERK signaling. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that AEG-1−/− primary mouse hepatocytes responded to EGF treatment, with activation of EGFR and MAPK/ERK, to the same level compared to WT hepatocytes (Robertson et al., 2014), indicating that AEG-1 is not required for normal activation of MAPK/ERK but its overexpression results in production of aberrant ligands, such as FXII, activating MAPK/ERK pathway. Activation of MAPK/ERK results in activation of the transcription factor AP-1 and it was documented that AEG-1 knockdown results in marked inhibition of AP-1 DNA binding in prostate cancer cells (Kikuno et al., 2007).

8. Cooperation/interaction of AEG-1 with other oncogenes/proteins to promote HCC

As a scaffold protein, AEG-1 interacts with many different proteins and protein complexes to mediate its action. Some of these interactions, leading to activation of specific oncogenic signaling pathways, have been described in the previous section. Here we highlight additional seminal interactions which helps AEG-1 execute its functions.

8.1. AEG-1 co-operates with c-Myc to promote hepatocarcinogenesis

In HCC, c-Myc is often overexpressed and functions as a driver oncogene for the induction and maintenance of the neoplastic state as indicated by the studies involving c-Myc overexpression mouse models (Coulouarn et al., 2006; Murakami et al., 1993; Shachaf et al., 2004). AEG-1 is transcriptionally regulated by c-Myc, and can control c-Myc expression by a variety of mechanisms, such as by activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway and by interacting with and inhibiting a transcriptional repressor PLZF thereby facilitating c-Myc-mediated transcription (Lee et al., 2006; Thirkettle, Mills, et al., 2009; Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). Both AEG-1 and c-Myc genes are located at human chromosome 8q and co-amplified in HCC patients. A transgenic mouse with hepatocyte-specific overexpression of both AEG-1 and c-Myc (Alb/AEG-1/c-Myc) developed highly aggressive, metastatic HCC, both spontaneously and following DEN exposure, as compared with transgenic mice having overexpression of either oncogene alone (Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015). Alb/AEG-1/c-Myc hepatocytes showed strong and sustained activation of various pro-survival signaling pathways as well as positively altered EMT. Indeed, in in vitro assays Alb/AEG-1/c-Myc hepatocytes manifested the cancer hallmarks, such as proliferation, invasion and chemoresistance, at a significantly higher levels compared to Alb/AEG-1 or Alb/c-Myc hepatocytes. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis indicated that livers of Alb/AEG-1/c-Myc mice showed a distinct gene signature mimicking human HCC. Compared to the single transgenics, robust upregulation of various ncRNAs, e.g., Rian, Mirg, and Meg3, was observed only in the double transgenic mice. Knocking down these ncRNAs considerably reduced proliferation and invasion by Alb/AEG-1/c-Myc hepatocytes, suggesting that these ncRNAs mediated AEG-1- and c-Myc-induced survival advantages. These studies unraveled a novel cooperative oncogenic effect of AEG-1 and c-Myc in HCC and Alb/AEG-1/c-Myc mouse model might serve as a valuable tool to evaluate novel therapeutic strategies targeting HCC (Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015).

8.2. AEG-1-SND1: A key interaction mediating AEG-1 function

Although many intracellular proteins that interact with AEG-1 have been identified, the most representative protein binding with high affinity is SND1 that provides interesting insights into the mechanism of action of AEG-1 (Blanco et al., 2011; Wan, Lu, et al., 2014; Yoo, Santhekadur, et al., 2011). Two independent approaches, namely yeast two-hybrid screening using a human liver cDNA library, and co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) followed by mass spectrometry, identified SND1 as the protein which most strongly interacts with AEG-1 (Yoo, Santhekadur, et al., 2011). A similar strategy also identified AEG-1-SND1 interaction in breast cancer cells (Blanco et al., 2011). SND1, also known as p100 coactivator or Tudor staphylococcal nuclease (Tudor-SN), is a multifunctional protein regulating a variety of cellular processes like transcription (Leverson et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2010), RNA splicing (Gao et al., 2012), and RNA metabolism (Gao et al., 2010). SND1 can be found both in the nucleus and cytoplasm. It facilitates transcription as a co-activator and mRNA splicing through interaction with the spliceosome machinery in the nucleus (Yang et al., 2007). In the cytoplasm, it acts as a nuclease in the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) in which small RNAs (e.g., siRNAs or miRNAs) are complexed with ribonucleoproteins to carry out RNAi-mediated gene silencing (Caudy et al., 2003). It was documented that AEG-1 interacts with SND1 in the cytoplasm and both AEG-1 and SND1 are required for optimum RISC activity (Yoo, Santhekadur, et al., 2011). It has been demonstrated that. Increased RISC activity, granted by AEG-1 or SND1, was found to result in increased degradation of tumor-suppressor mRNAs, which are targets of oncogenic miRNAs, including the mRNA of the tumor suppressor PTEN, a target of miRNA-221 which is overexpressed in HCC (Yoo, Santhekadur, et al., 2011). Interestingly, SND1 is highly expressed in HCC, SND1 overexpression increased and SND1 knockdown abrogated growth of human HCC xenografts in nude mice and a transgenic mouse with hepatocyte-specific overexpression of SND1 (Alb/SND1) developed spontaneous and augmented DEN-induced HCC. (Jariwala et al., 2017; Yoo, Santhekadur, et al., 2011). SND1 promoted expansion of tumor-initiating cells (TICs) in Alb/SND1 mice (Jariwala et al., 2017). A selective SND1 inhibitor, 3′,5′-deoxythymidine bisphosphate (pdTp), inhibited AEG-1-induced increased proliferation of human HCC cells, and effectively reduced tumor burden in human xenograft models of subcutaneous or orthotopic HCC (Jariwala et al., 2017; Yoo, Santhekadur, et al., 2011). SND1 regulates HCC angiogenesis by the activation of NF-κB and miR-221 inducing angiogenic factors like CXCL16 (Santhekadur, Das, et al., 2012). Using a variety of mouse models, a key role of AEG-1 in expansion of TICs in breast cancer was elucidated, facilitating metastasis, and it was documented that AEG-1 exerted its effect by interacting and stabilizing SND1 (Wan, Lu, et al., 2014). Under steady-state condition SND1 levels did not differ between WT and AEG-1 knocked-down cells. However, upon induction of DNA replication stress, a common type of stress during tumor development, half-life of SND1 protein was significantly reduced in AEG-1 knocked-down cells compared to control indicating that AEG-1-SND1 interaction is required for survival under stressful condition, e.g., during tumor initiation (Wan, Lu, et al., 2014). Similarly, overexpression of AEG-1 showed increased stabilization of SND1 upon heat shock (Guo et al., 2014). AEG-1 mutants, which failed to interact with SND1, lost their tumor-initiating potential (Guo et al., 2014; Wan, Lu, et al., 2014). The importance of SND1 in AEG-1-mediated oncogenesis has been shown in additional cancers (He et al., 2020), and collectively, these studies show a seminal role of AEG-1-SND1 interaction in carcinogenesis.

8.3. AEG-1 regulates metabolic functions by interacting with RXR

RXR is a ligand-dependent transcription factor that functions as a key regulator of cell growth, differentiation, metabolism and development (Lefebvre, Benomar, & Staels, 2010). RXR heterodimerizes with one third of the 48 human nuclear receptor superfamily members, including retinoic acid receptor (RAR), thyroid hormone receptor (TR), vitamin D receptor (VDR), Liver X Receptor (LXR), Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor (PPAR) and Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR), and regulates corresponding ligand-dependent gene transcription. Cholesterol metabolites, fatty acid derivatives and bile acids serve as endogenous ligands for LXR, PPAR and FXR, respectively, which play important role in regulating lipid metabolism (Lefebvre et al., 2010). In the absence of ligand, RXR heterodimers interact with co-repressors that maintain histones in a deacetylated state and inhibit transcription. Upon ligand binding there is a conformational change so that the co-repressors are replaced by co-activators inducing histone acetylation and transcriptional activation. The co-activators harbor a unique LXXLL motif through which they interact with the transcription factors (Heery, Kalkhoven, Hoare, & Parker, 1997). Interestingly AEG-1 also harbors an LXXLL motif and yeast two-hybrid assay using the region of AEG-1 harboring the LXXLL motif identified RXR as its interacting partner (Srivastava et al., 2014). We documented that in the nucleus, interaction of AEG-1 with RXR blocks co-activator recruitment thereby abrogating retinoic acid-, thyroid hormone and fatty acid-mediated gene transcription (Srivastava et al., 2014, 2017, Srivastava, Robertson, et al., 2015). Knocking down AEG-1 markedly augmented retinoic acid-mediated killing and this concept was used to develop and evaluate a therapeutic protocol in mouse models (Rajasekaran, Srivastava, et al., 2015; Srivastava et al., 2014). Non-thyroidal illness syndrome (NTIS), characterized by low serum 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine (T3) with normal l-thyroxine (T4) levels, is associated with malignancy and decreased activity of type I 5′-deiodinase (DIO1), which converts T4 to T3, contributes to NTIS (Warner & Beckett, 2010). T3 binds to TR/RXR heterodimer and regulate transcription of target genes, including DIO1. It was demonstrated that AEG-1 overexpression repressed and AEG-1 knockdown induced DIO1 expression (Srivastava, Robertson, et al., 2015). An inverse correlation was observed between AEG-1 and DIO1 levels in human HCC patients. Low T3 with normal T4 was observed in the sera of HCC patients and Alb/AEG-1 mice (Srivastava, Robertson, et al., 2015). Altogether these observations suggested that AEG-1 might play a role in NTIS associated with HCC and other cancers.

The RXR inhibitory activity allows AEG-1 to profoundly regulate lipid metabolism. AEG-1−/− mice are significantly leaner with prominently less body fat compared to the WT (AEG-1+/+) littermates (Robertson, Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015). When fed high fat and cholesterol diet (HFD), WT mice rapidly gained weight while AEG-1−/− did not gain weight at all even thought their food intake was similar. AEG-1−/− mice showed decreased fat absorption from the intestines because of increased activity of LXR and PPARα (Robertson, Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015). In enterocytes, activation of LXR inhibits cholesterol absorption by downregulating cholesterol transporter Npc1l1 and upregulating cholesterol efflux proteins, Abca1, Abcg5 and Abcg8. Activation of PPARα in the enterocytes promotes β-oxidation of absorbed fatty acids (FA) thereby downregulating fatty acid absorption into the circulation. Thus, increased activity of LXR and PPARα in AEG-1−/− enterocytes impaired overall fat absorption contributing to leanness (Robertson, Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015). On the contrary, Alb/AEG-1 mice developed spontaneous NASH and AEG-1ΔHEP mice were protected from HFD-induced NASH (Srivastava et al., 2017). One underlying mechanism of increased steatosis in Alb/AEG-1 mice is inhibition of PPARα-mediated FA β-oxidation allowing accumulation of fat in the liver (Srivastava et al., 2017). Thus AEG-1-RXR interaction has profound implication in regulating metabolism as well as functions of vitamins and hormones, especially in the liver.

9. AEG-1 binds to RNA: Regulation of translation

Several RNA interactome screen identified AEG-1 as a selective ER mRNA-binding protein (Baltz et al., 2012; Castello et al., 2012; Chen, Jagannathan, Reid, Zheng, & Nicchitta, 2011; Kwon et al., 2013). In a recent study it was confirmed that AEG-1 is an ER-resident integral membrane RNA-binding protein (RBP) (Hsu et al., 2018). Analysis of AEG-1 RNA interactome by HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP methods revealed an enrichment for endomembrane organelle-encoding transcripts, most prominently those encoding ER-resident proteins as well as integral membrane protein-coding RNAs (Hsu et al., 2018). Secretory and cytosolic protein encoding mRNAs were also represented in the AEG-1 RNA interactome, with the latter category enriched in genes functioning in mRNA localization, translational regulation and RNA quality control. AEG-1 does not have a consensus RNA-binding domain and deletion mapping analysis identified the central disordered region of AEG-1, comprised of a.a. 138–350 to bind to RNA (Hsu et al., 2018). These findings corelate nicely with several of our previous findings. We showed that overexpression of AEG-1 increases protein levels, and not mRNA levels, of multidrug resistance gene 1 (MDR1) contributing to chemoresistance, FXII contributing to angiogenesis, and fatty acid synthase (FASN) contributing to de novo lipogenesis, hence NASH (Srivastava et al., 2012, 2017; Yoo, Chen, et al., 2010). All these three proteins are endomembrane or secreted and we documented that AEG-1 facilitates association of all three mRNAs with polysomes resulting in increased translation (Srivastava et al., 2012, 2017; Yoo, Chen, et al., 2010). It should be noted that in addition to FASN, AEG-1 bound mRNAs also code for additional fatty acid synthesizing enzymes, and in Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of AEG-1 bound mRNAs encoding endomembrane proteins, lipid metabolism-associated proteins came out to be the most significant category (Hsu et al., 2018). Thus AEG-1 promotes NASH by translational upregulation of enzymes of de novo lipogenesis, inhibition of PPARα-mediated FA β-oxidation and stimulation of inflammation by activating NF-κB (Fig. 4). A separate study also identified AEG-1 as an RBP in endometrial cancer cells by RNA immunoprecipitation followed by microarray (Meng et al., 2012). However, the RNA interactome was not characterized and it was documented that protein levels of two AEG-1-interacting mRNAs, PDCD11 and KDM6A, were increased in AEG-1 knockdown cells, and the consequence of this observation was not studied (Meng et al., 2012).

Fig. 4.

Mechanisms by which AEG-1 induces NASH. AEG-1 binds to RXR using LXXLL motif which inhibits PPARα and decreases fatty acid β-oxidation. AEG-1 binds to specific mRNAs increasing translation of lipogenic enzymes thus increasing de novo lipogenesis. These two events lead to increased steatosis. AEG-1 activates NF-κB by multiple mechanisms. It binds to p65 subunit of NF-κB and functions as a bridging factor between NF-κB and basal transcription machinery. It interacts with upstream ubiquitinated molecules of NF-κB pathway such as TRAF2 and RIP1. It is directly phosphorylated by IKKβ which is necessary for subsequent IKKβ-mediated phosphorylation of IκBα leading to its proteasomal degradation and translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus. NF-κB activation leads to increased inflammation. Thus AEG-1 increases both steatotic and inflammatory components of NASH. Image created using tools from Biorender.

10. AEG-1 and hallmarks of cancer: Specific examples

By its pleiotropic action AEG-1 has the ability to augment all hallmarks of cancer as described by Hanahan and Weinberg (2011) leading to tumor initiation and progression. Here we highlight unique aspects of AEG-1 regulating some of these hallmarks with particular focus on HCC.

10.1. AEG-1 and resistance to therapy

Resistance developed after the commencement of treatment is a major obstacle that an oncologist confronts during cancer treatment. AEG-1 over-expression in cancer plays a crucial role in conferring resistance to chemotherapy (chemoresistance). Response to various chemotherapeutics, e.g., doxorubicin (Dox), cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), is markedly blunted due to higher expression of AEG-1 in neoplastic tissues (Meng, Thiel, & Leslie, 2013). Chemotherapy may be administered to HCC patients whose cancer cannot be removed by surgery, has not responded to local therapies such as ablation or embolization, or when targeted therapy is no longer helpful. Doxorubicin (Dox) is a common anticancer drug used for the treatment of HCC, but the clinical efficacy of Dox is not profound thus emphasizing an inherent resistance of HCC cells to Dox (Kato et al., 2001). ABC transporters are ATP-dependent efflux pumps with broad drug specificity overexpression of which contribute to chemoresistance. AEG-1 overexpression resulted in marked upregulation of MDR1 (ABCB1) protein by increased translation resulting in increased efflux of Dox and promotion of Dox-resistance in HCC cells (Yoo, Chen, et al., 2010). While, AEG-1 can directly bind to MDR1 mRNA and increase its translation (Hsu et al., 2018), it was documented that inhibition of PI3K/Akt pathway could also inhibit AEG-1-mediated polysome association of MDR1 mRNA (Yoo, Chen, et al., 2010), indicating that AEG-1 modulates MDR1 translation by multiple ways. AEG-1 overexpression increased phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G), but not mTOR-sensitive eIF4E and 4E-BP, and interestingly this activation was not blocked by PI3K/Akt inhibitor, indicating that AEG-1 can stimulate the translational machinery in a PI3K/Akt/mTOR-independent pathway (Yoo, Chen, et al., 2010). In-depth protein-protein interaction studies need to be carried out to elucidate the underlying mechanism of this phenomenon. Resistance to 5-FU, another chemotherapeutic used to treat HCC, can also be conferred by AEG-1 (Yoo, Gredler, et al., 2009). Gene expression analysis of AEG-1-overexpressed human HCC cells identified upregulation of several genes, e.g., drug-metabolizing enzymes like dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD) and the transcription factor late SV40 factor (LSF/TFCP2), by AEG-1 (Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). LSF transcriptionally regulates thymidylate synthase (TS), the substrate for 5-FU, and upregulation of LSF by AEG-1 induced TS (Yoo, Gredler, et al., 2009). Thus, the dual inhibitory effects produced by AEG-1, i.e., increase in the 5-FU catabolizing enzyme DPYD, and increase in 5-FU substrate TS, resulted in significant resistance to 5-FU. A lentivirus expressing AEG-1 short hair-pin RNA in combination with Dox or 5-FU dramatically inhibited growth of aggressive human HCC, compared to either agent alone, in nude mice xenograft experiments (Yoo, Chen, et al., 2010; Yoo, Gredler, et al., 2009). Subsequent studies identified overexpression of LSF in HCC and unraveled its role as an oncogene via transcriptional regulation of osteopontin, resulting in activation of hepatocyte growth factor receptor c-Met, and that of MMP-9, and a small molecule inhibitor of LSF abrogated HCC in an endogenous HCC model (Grant et al., 2012; Rajasekaran, Siddiq, et al., 2015; Santhekadur, Gredler, et al., 2012; Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2010, Yoo, Gredler, et al., 2011). Interestingly, studies using breast cancer cells showed resistance to broad-spectrum chemotherapeutics conferred by AEG-1 that involves upregulation of aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, member A1 (ALDH3A1) and c-Met (Hu et al., 2009).

Another mechanism by which AEG-1 causes chemoresistance is by induction of protective autophagy (Bhutia et al., 2010). Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved process that can be observed in all cells, maintaining cellular homeostasis by removing cellular contents through the lysosomal compartment for degradation (Das, Banerjee, & Mandal, 2020). Overexpression of AEG-1 induced protective autophagy in multiple cell types by activating AMPK/mTOR pathway leading to increased expression of the autophagy regulator ATG5, and inhibition of AEG-1-induced autophagy in cancer cells enhanced sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents (Bhutia et al., 2010). However, the mechanism by which AEG-1 induces an energy-deprived state leading to activation of AMPK remains to be determined. Altogether these studies suggest that localized inhibition of AEG-1 might be a good strategy to re-sensitize HCC with chemotherapy treatment.

Like chemoresistance, failure of radiotherapy is a major clinical challenge owing to the radio-resistance in the course of treatment. It has been reported that Aurora-A confers radio-resistance in HCC by upregulating the NF-κB signaling pathway (Shen et al., 2019). As AEG-1 also activates NF-κB, AEG-1 may likely have a role in conferring radio-resistance in HCC, which has been shown for other cancers (Zhao et al., 2012).

10.2. AEG-1 and senescence

Senescence is a potential anti-cancer mechanism and is characterized by a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (Collado & Serrano, 2010). Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-7 (IGFBP7) is a secreted protein that induces senescence in cancer cells and functions as a tumor suppressor in HCC (Akiel et al., 2017; Chen, Yoo, et al., 2011). IGFBP7 was identified as the most robustly downregulated gene by AEG-1 in HCC (Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009) and forced overexpression of IGFBP7 in AEG-1-overexpressing HCC cells inhibited in vitro growth and induced senescence, and suppressed in vivo tumor growth in nude mice (Chen, Yoo, et al., 2011). These findings suggest that AEG-1 protects from senescence by downregulating IGFBP7. Primary hepatocytes, mouse and human, do not divide in vitro and starts becoming senescent after 96 h. It was documented that lentivirus-mediated overexpression of AEG-1 markedly protected human hepatocytes from induction of senescence and Alb/AEG-1 hepatocytes showed a significant reduction and delay in senescence compared to WT hepatocytes (Srivastava et al., 2012; Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015). Senescence is associated with activation of DNA damage response (DDR), leading to activation of ATM and ATR, their downstream kinases CHK1 and CHK2 leading to p53 phosphorylation and increase in p53 and p21 levels, which was markedly dampened in Alb/AEG-1 hepatocytes compared to WT (Srivastava et al., 2012; Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015). DNA-damaging agent DEN induces DDR in hepatocytes leading to senescence and/or apoptosis which functions as a protective mechanism. If the hepatocytes still survive following DEN treatment the ensuing DNA damage mutagenizes and transforms them. AEG-1ΔHEP mice are protected from DEN-induced HCC, and it was demonstrated that DEN-induced DDR is significantly augmented in AEG-1−/− hepatocytes leading to senescence and apoptosis compared to their WT counterparts (Robertson et al., 2018). AEG-1 can interact with MDM2 resulting in stabilization of MDM2 protein precluding p53 activation (Ding et al., 2019). However, the mechanism by which AEG-1 interferes with the initial steps of DDR remains to be elucidated.

10.3. AEG-1 promotes angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is a fundamental requirement for the development of any solid tumor (Folkman, 1971; Kerbel, 2000). AEG-1-overexpressing human HCC cells generated highly vascular tumors in nude mice associated with increased expression of angiogenic factors, such as VEGF, placental growth factor (PIGF) and FGFα (Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). Stable overexpression of AEG-1 in normal immortal cloned rat embryo fibroblast (CREF) transformed them and allowed them to form highly vascular tumors characterized by enhanced expression of biomarkers of angiogenesis, e.g., angiopoietin-1, Tie 2 and HIF-1α (Emdad et al., 2009). In vitro analysis documented that activation of PI3K/Akt pathway plays a role in regulating angiogenesis by AEG-1 (Emdad et al., 2009). Similarly, conditioned media (CM) from Alb/AEG-1 hepatocytes, but not from WT hepatocytes, induced a marked angiogenic response in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) differentiation assay and chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay (Srivastava et al., 2012). Further studies documented that trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) and FXII, secreted from Alb/AEG-1 hepatocytes, played a seminal role in mediating AEG-1-induced angiogenesis, especially proliferation and differentiation of endothelial cells (Srivastava et al., 2012). Both hypoxia and glucose deprivation, stimulators of angiogenesis, induced AEG-1 by HIF-1α activation and ROS generation, respectively, and the induced AEG-1 then protected from stress and supported survival in glioma cells (Noch, Bookland, & Khalili, 2011).

10.4. AEG-1 promotes metastasis

AEG-1 was cloned as a metastasis-promoting gene for breast cancer and since then extensive research has confirmed the pivotal role of AEG-1 in facilitating invasion and metastasis of many types of cancer including HCC (Brown & Ruoslahti, 2004; Emdad et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2009; Kikuno et al., 2007; Srivastava et al., 2012; Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015; Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). The importance of AEG-1 in metastasis is emphasized by its inclusion in MammaPrint, the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved individualized metastasis risk assessment assay for breast cancer patients. The predictive diagnostic test MammaPrint includes 70 genes including AEG-1 for assessment. Gradually higher expression of AEG-1 is detected with the progression of different cancers, especially overexpression of AEG-1 can be observed in the metastatic stage of the disease (Sarkar & Fisher, 2013).

Overexpression of AEG-1 in human HCC cells markedly increased in vitro invasion and induced lung metastasis in in vivo xenograft assays (Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). As a corollary, the most robust phenotype observed upon knockdown of AEG-1 in HCC cells was in vitro invasion (Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). Similarly knocking down AEG-1 in human HCC cells resulted in reduced pulmonary and abdominal metastases in nude mice and was associated with alterations in EMT markers, namely, down-regulation of N-cadherin and snail, upregulation of E-cadherin, and increased cytoplasmic localization of β-catenin (Zhu et al., 2011). Under naı¨ve condition, Alb/AEG-1 mice did not develop spontaneous HCC, Alb/c-Myc mice developed spontaneous HCC without distant metastasis, and Alb/AEG-1/c-Myc mice developed highly aggressive HCC with frank lung metastasis, emphasizing the role of AEG-1 in promoting metastasis (Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015). DEN-induced carcinogenesis was significantly accelerated in all three groups with most markedly pronounced effect with lung metastasis in Alb/AEG-1/c-Myc mice.AEG-1 or c-Myc alone was able to induce EMT signaling pathways in hepatocytes, but activation of these pathways was sustained Alb/AEG-1/c-Myc hepatocytes (Srivastava, Siddiq, et al., 2015). Tetraspanin 8 (TSPN8), a cell surface protein known to play a role in metastasis was found to be robustly increased in AEG-1-overexpressing human HCC cells, and TSPN8 knockdown markedly inhibited AEG-1-induced in vitro invasion and intrahepatic metastasis in an orthotopic xenograft model, suggesting a potential role of TSPN8 in AEG-1-induced metastasis of HCC cells (Akiel et al., 2016; Yoo, Emdad, et al., 2009). Resistance to anoikis is an important component for survival of cancer cells in circulation to establish metastasis (Kim, Koo, Sung, Yun, & Kim, 2012).AEG-1 expression was found to be enhanced in HCC cells grown in suspension culture and AEG-1 could promote anoikis resistance of detached HCC cells (Zhu, Liu, et al., 2020). A role of AEG-1-induced autophagy in conferring anoikis resistance was suggested and inhibition of autophagy prevented AEG-1-induced metastasis of HCC xenografts to liver and lungs of nude mice (Zhu, Liu, et al., 2020). A potential role of protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK)-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP signaling axis was implicated in regulating AEG-1-induced autophagy in HCC cells (Zhu, Liu, et al., 2020). In a separate study it was shown that elevated AEG-1 expression promoted anoikis resistance and orientation chemotaxis of HCC cells toward human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMEC) through the activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and the metastasis-associated chemokine receptor CXCR4, respectively (Zhou et al., 2014). It was documented that HPMEC secreted CXCL12, the ligand for CXCR4, and CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 reduced AEG-1-induced orientation chemotaxis (Zhou et al., 2014). A role of AEG-1-PRMT5 interaction leading to activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway and promoting AEG-1-induced metastasis of HCC cells has been described (Zhu, Peng, et al., 2020). Collectively, these results suggest that AEG-1 positively regulates HCC cell metastasis by multiple mechanisms.

11. AEG-1 targeting as a potential therapy for HCC

There is no effective therapy for advanced-stage HCC, and most of the FDA-approved drugs increase patient survival for only ~3 months compared to placebo in non-resectable HCC patients (Abou-Alfa et al., 2018; Bruix et al., 2017; Kudo et al., 2018; Llovet et al., 2008; Rimassa et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2019). HCC develops on a cirrhotic background with compromised liver function which markedly interferes with the ability of the liver to detoxify drugs. Hence drug-induced toxicity is a major limiting factor for treating HCC patients, and relatively non-toxic gene- and immune-based therapies are being increasingly appreciated as the treatment of choice (Reghupaty & Sarkar, 2019). Mouse model studies have clearly established AEG-1 as a key driver of advanced AEG-1 and as such targeting AEG-1 should be a viable and effective strategy for treating HCC. As yet no small molecule inhibitor for AEG-1 exists. However, RNA-interference (RNAi) strategy to inhibit AEG-1 can be effective in HCC. Indeed, nanoparticle-delivered siRNA targeting oncogenes has shown strong efficacy in inhibiting HCC in pre-clinical models as well as in phase I trials (Bogorad et al., 2014; Dudek et al., 2014; Tabernero et al., 2013). We have developed hepatocyte-targeted nanoplexes by conjugating polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers with polyethylene glycol (PEG) and galactose lactobionic acid (PAMAM-PEG-Gal) which were complexed with AEG-1 siRNA (PAMAM-AEG-1si) (Rajasekaran, Srivastava, et al., 2015; Srivastava et al., 2017). PAMAM complexes and compacts siRNA, PEG reduces charge density and increases circulation half-life, and lactobionic acid binds to asialoglycoprotein receptors overexpressed selectively in hepatocytes thus allowing targeted uptake (Rajasekaran, Srivastava, et al., 2015). AEG-1 overexpression inhibits anti-tumorigenic activity of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) (Srivastava et al., 2014). In a nude mice orthotopic human HCC xenograft assay, we documented that ATRA alone had no effect on tumor growth, PAMAM-AEG-1si alone significantly inhibited tumor growth, and the combination of PAMAM-AEG-1si and ATRA completely eliminated the tumors without exerting any toxicity (Rajasekaran, Srivastava, et al., 2015). In a separate study, we showed that PAMAM-AEG-1si could effectively protect C57BL/6 mice from HFD-induced NASH development (Srivastava et al., 2017). Thus PAMAM-AEG-1si could be a therapeutic strategy for HCC as well as a preventive strategy by inhibiting NASH and thereby preventing NASH to progress into HCC. AEG-1 knockdown markedly augmented anti-HCC activity of Dox and 5-FU, indicating that PAMAM-AEG-1si can be combined with standard chemotherapy or TKIs. AEG-1 plays a profound role in regulating macrophage function and inflammation, and as such PAMAM-AEG-1si can also be combined with anti-inflammatory strategies and immunotherapy. In-depth studies using endogenous mouse models of HCC need to be performed to evaluate these strategies for their potential transition to the clinics. A recent study described therapeutic efficacy of locked nucleic acid (LNA)-modified AEG-1 antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) in inhibiting primary tumor growth and attenuating metastasis of syngeneic breast, colorectal and lung tumors in C57BL/6 mice (Shen et al., 2020).

Very recently the interaction between AEG-1 and SND1 was exploited to design a peptide that can inhibit AEG-1-SND1 interaction (Li et al., 2021). AEG-1-interacting domains of SND1 were used as bait in a phage display screening to identify a 12 a.a. peptide which could disrupt AEG-1-SND1 interaction in vivo, induce SND1 degradation, and inhibit growth of human breast cancer xenografts (Li et al., 2021). This is an exciting development which needs to be evaluated in other cancers and opens up modification of this strategy for generating clinically relevant peptidomimetics or small molecule inhibitors.

12. Challenges and future perspectives