Abstract

Background:

Close relatives provide much of the care to people with cancer. As resilience can shield family caregivers from mental health problems, there has been a burgeoning interest in resilience-promoting interventions. However, the evidence necessary for the development of these interventions is scant and unsynthesized.

Aim:

To create an overall picture of evidence on resilience in cancer caregiving by a theory-driven meta-synthesis.

Design:

In this systematically constructed review a thematic synthesis approach has been applied. The original findings were coded and structured deductively according to the theoretical framework. Consequently, the codes were organized inductively into themes and subthemes.

Data sources:

Through September 2019, five electronic databases were searched for qualitative studies on resilience in cancer caregiving. The search was extended by a supplementary hand search. Seventeen studies met the eligibility criteria.

Results:

The elements of resilience, as described in the pre-defined theoretical framework of Bonanno, are reflected in the lived experiences of family caregivers. The resilience process starts with the diagnosis of advanced cancer and may result in mental wellbeing, benefit finding, and personal growth. The process is influenced by context elements such as individual history, sociocultural background, caregiver characteristics, and the behavior of the supportive network. A repertoire of coping strategies that caregivers use throughout the caregiving process moderates the resilience process.

Conclusion:

This review and theoretical synthesis reveal key elements of resilience in the process of cancer caregiving, including influencing factors and outcomes. Implications and avenues for further research are discussed.

Keywords: Resilience, caregivers, advanced cancer, palliative care, systematic review

What is already known about the topic?

Resilience is conceptualized as a process that starts from a potentially traumatic event (such as a family member diagnosed with advanced cancer). It is influenced by baseline adjustments and resilience predictors, leading to a resilient outcome.

Resilience may protect against mental distress and major psychological problems such as depression or anxiety.

What this paper adds?

Resilience in cancer caregiving corresponds to the four temporal elements from the framework developed by George A. Bonanno.

The four coping strategies are the mechanisms by which the context elements can result in resilient outcomes.

Implications for practice, theory, or policy

This review may enhance insights into resilience in caregivers of patients diagnosed with advanced cancer and the role of coping strategies.

The inadequacy of focusing exclusively on how caregivers manage the situation is underlined.

These new insights can be used in the development of resilience supporting interventions and in clinical practice.

Introduction

Most people with advanced cancer prefer to be cared for at home.1,2 This task is usually taken up by informal caregivers, defined as people who provide care to relatives usually without payment. 3 Being the informal caregiver of a relative with advanced cancer can be burdensome and caregivers are at risk for physical, psychological, and social dysfunction.4,5 Although a cancer diagnosis can be considered a potentially traumatic event 6 for family members as well as for patients, clinical practice suggests that most family caregivers seem to adapt well and return to a status of mental wellbeing. This process, known as “resilience,” is often observed after a major disruptive event.7,8

Resilience may protect against mental distress and major psychological problems such as depression or anxiety.9,10 As a result, there is an increasing interest in resilience-promoting interventions in cancer caregiving. However, much is still unknown, as the interpretation and synthesis of the existing evidence on resilience has been hampered due to conceptual heterogeneity and a variety of labels used for the same or closely related concepts. For instance, although research on adaptive coping, a concept closely related to resilience, could enhance insights into the resilient process, not all studies on positive coping mention the word resilience. 11 Hence, authors risk overlooking these studies when synthesizing the evidence. The hermeneutic review by Opsomer et al. 6 clarifies this matter. Based on the APA definition of resilience 12 and the theoretical framework of Bonanno et al. 13 the authors suggest approaching resilience as “the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, threats, and significant sources of stress.” 12 Resilience is conceptualized as a process that starts from a potentially traumatic event, is influenced by baseline adjustments and resilience predictors, and leads to a resilient outcome. 13 The suggested definition and framework are considered the most comprehensive of all definitions and frameworks included in the review. 6 Although the results of the hermeneutic review 6 support a multifaceted approach of the resilience concept, relying on the APA definition of resilience may lead to the exclusion of quantitative studies that do not approach resilience as a process but as a measurable trait. On the contrary, qualitative studies expressing resilience through a variety of terminology found within the APA definition could be included. Hence, a novel, innovative, and holistic, approach toward the elements of resilience was facilitated. This holistic approach distinguishes this synthesis from other systematic reviews that focus on only one element of resilience (e.g. resilient outcome or ego-resiliency).

The aim of this theory-driven meta-synthesis is fourfold: (1) to create an overall picture by synthesizing the body of evidence on resilience in cancer caregiving, (2) to achieve robust and broad conclusions that go beyond the results of the original studies by re-analyzing their findings, (3) to seek how closely the literature on resilience in cancer caregiving fits within an integrative process-oriented theory, namely the proposed theoretical framework of Bonanno et al., 13 and (4) to discover if new ideas or powerful explanations on the phenomenon might emerge from the review process. 14

The research question addressed is “How are the elements of resilience expressed in research on advanced cancer caregiving?”

Methods

Protocol and reporting

The study protocol was submitted to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on April 3, 2020 and published on July 5, 2020, with registration number CRD42020161476. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020161476.

The reporting of this systematic review is based upon the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) Statement. 15

Synthesis methodology

A systematically-conducted meta-synthesis was performed to synthesize findings from qualitative studies that explored resilience in advanced cancer caregiving.14,16 A thematic synthesis approach was applied to reanalyze the findings of the original studies. 17 “Thematic synthesis” is a well-investigated, rigorous, and explicit methodology used in the conduct of systematic reviews of qualitative data on people’s perspectives and experiences. 17 This methodology seemed the most appropriate means to synthesize the findings of the primary studies in order to provide an answer to our research question, and hence to gain insight into the expression of resilience in cancer caregiving.

Literature search and selection

Five electronic databases (Medline/PubMed, Embase, Cinahl, Web of Science, and PsycInfo) were searched by the first author (SO) between March and September 2019. Weekly e-mail alerts were set for all databases. The PubMed and the Embase search were repeated every 6 months until the analysis was finished (September 2020). Neither the e-mail alerts nor the repeated search revealed additional papers.

The search was developed with the help of an academic librarian and was intended to be as comprehensive as necessary to detect all available studies on the research topic. The search string for Medline was pilot-tested for sensitivity. Research on resilience in advanced cancer caregiving is scarce, and hence a sensitive search string, bringing most relevant studies to the front, was prioritized over a specific search string. The search strings included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) or Emtree terms, title and abstract words, and truncation. The search terms were related to the following MeSH-terms “caregivers” or “family” or “friends” and “resilience psychological” or “emotional adjustment” or “adaptation psychological” or “post traumatic growth” or “self-efficacy” and “neoplasm metastasis” or “neoplasms.” The complete search strings for the five databases are provided in a Supplemental Material S1: “Search strategy.” No time limitations of publication were applied.

Inclusion criteria

-Studies on resilience in caregivers of people with advanced cancer or cancer in a palliative stage. A study is considered to enhance insight on resilience when the main topic fits the APA definition of resilience. 12 Consequently, studies on adapting well, coping well, bouncing back, finding benefits, and personal growth are eligible for inclusion. People with advanced cancer are defined as those diagnosed with cancer in stage III or IV or with metastatic cancer. People with cancer in a palliative stage are defined as patients for whom the goal of cure is no longer reasonable or with a life expectancy of 1 year or less, including terminally ill patients.

-Studies approaching resilience as a process.

-Peer-reviewed studies.

-Studies published in English and Dutch.

Exclusion criteria

-Studies on themes related to resilience without meeting the APA-definition of resilience 12 (e.g. hope, self-efficiency, sense of coherence) or studies approaching resilience as a measurable trait (quantitative studies).

-Studies on resilience in cancer survivors or during treatment with curative intent.

-Studies in which the cancer stage is unknown or unclear.

-Studies on resilience in settings other than cancer caregiving (e.g. studies on family resilience, couple resilience, or community resilience).

-Studies in children or adolescents younger than 18 years of age (both patients and caregivers).

-Articles published in predatory journals or by predatory publishers listed on Beall’s or Cabell’s predatory list. Predatory journals and publishers deviate from best editorial and publication practices (e.g. no rigorous peer-review process). They are characterized by a lack of transparency or by the use of aggressive and indiscriminate solicitation practices. 18

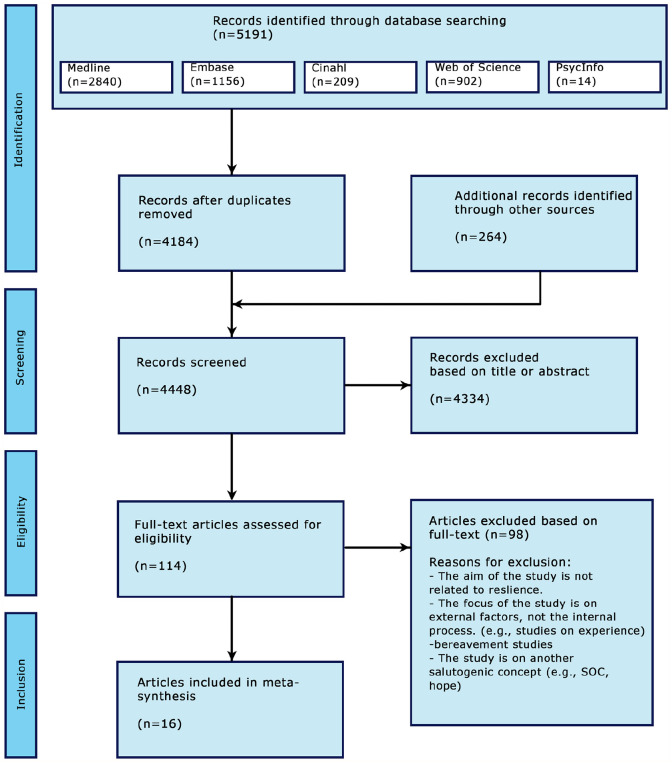

After removing duplicates, the manuscripts found were uploaded in Rayyan, an online tool developed to ease the selection process. 19 Consequently, two authors (SO and EL) independently screened the title and abstract of all hits against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full text of all manuscripts that were considered by at least one of the two authors was assessed for eligibility by both authors. Manuscripts agreed upon were included. Conflicting manuscripts were assessed for eligibility by the two supervising authors (JDL and PP), discussed within the authors team, and inclusion or exclusion was decided by consensus. Starting from this preliminary selection, all references and citations were assessed through an extensive snowball search. Eventually, a supplementary manual search in palliative care journals and in the bibliography of key publications was performed by the first author (SO). In cases of conflict, selection was discussed between authors until consensus was reached. A flow diagram of the screening process, including the numbers of studies screened, studies assessed for eligibility, studies included and excluded in the review, and the primary reasons for exclusion is provided as Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Seventeen studies on resilience in cancer caregiving qualified for inclusion in the review.11,20–35

Quality appraisal

To be confident that our findings are grounded in adequate data and to avoid drawing unreliable conclusions, a quality appraisal according to The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) was performed.17,36 Two authors (SO and EL) independently assessed the quality of all included studies. The final assessment was made by consensus after discussing the conflicts. There were no differences that required the intervention of a third author. Unmet criteria are disclosed in Table 1. An overview of the critical appraisal is provided as Supplemental Material S3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies and critical appraisal.

| Author | Region | Aim | Methods | Number of participants | Age group | Study population/relation to the patient | Patient characteristics | Part of a larger study? | Critical appraisal unmet criteria* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rose et al. 20 | UK, Europe | To gain knowledge through understanding the lived experience of family caregivers of someone diagnosed with terminal cancer. | Based on literary criticism | 21 families | Unknown | Family caregiver | Patients diagnosed with cancer with a prognosis of less than 6 months or patients who recently died of cancer. | No | 1, 4, 6, 7 |

| Strang and Koop 21 | Canada, North America | To present findings related to how caregivers cope while caring for a dying family member at home. | Exploratory, interpretative, and descriptive study | 15 (11 women, four men) | 37–81 years (mean 58.5) | Nine spouses, four children, one sibling, one daughter in law | The patients died because of cancer one to 12 months before the first interview. | No | 5, 6 |

| Hudson 22 | Melbourne, Australia | To explore the challenges and positive aspects associated with supporting a relative or friend dying of cancer at home. | Thematic analysis | 47 (65% women) | Mean 60 years | 65% spouses | Patients with advanced cancer, with a life-expectancy <12 months and receiving metropolitan community palliative care. | Yes | 1, 4, 5, 6, 8 |

| Stajduhar et al. 23 | Western Canada, America | To describe factors that influence family caregivers’ ability to provide end-of-life cancer care at home. | Interpretive, descriptive approach | 29 (26 women, three men) | 40–85 years (mean 65) | 22 spouses, three children, three siblings, three parents | Patients with advanced cancer (brain, gastrointestinal, liver, lung, blood, ovarian, prostate, renal) in which the primary goal of treatment was palliative and who had a life expectancy of 6 months or less. | Yes | 6 |

| Wong et al. 24 | NSW, Australia | To extend previous research on positive aspects of informal cancer caregiving | Thematic analysis from a phenomenological perspective | 23 (18 women, five men) | 19–85 years (mean 57) | Primary family caregiver: (five children, one sibling, 14 life partners/spouses, one parent, two friends) | The patients died because of cancer (respiratory, breast, pancreatic, renal, brain, colorectal/gastro-intestinal, hematological, gynecological, prostate, mesothelioma). | Yes | 4, 6 |

| Wong and Ussher 25 | NSW, Australia | To examine bereaved informal caregivers’ accounts of positive aspects of providing palliative cancer care at home. | Social constructionist epistemology/thematic analysis | 22 (17 women, five men) | 19–71 years (mean 55.3) | Primary family caregiver: (five children, one sibling, 14 life partners/spouses) | The patients died because of cancer 1 month to 10 years before the interview (mean 26.8 months). | Yes | 4, 6 |

| Benkel et al. 26 | Sweden, Europe | To increase knowledge concerning what forms of coping strategies loved ones use when a family member is faced with an incurable cancer. | Interpretive content analysis | 20 | Most <65 years | Spouses, adult children, siblings, friends | Patients diagnosed with cancer (majority prostate or breast cancer). | No | 6 |

| Sand et al. 27 | Sweden, Europe | To investigate the question: “Why do people in a family choose to take responsibility when a member is stricken with a serious disease?” | Existential hermeneutics | 20 (12 women, eight men) | 16–79 years (mean 58) | 12 spouses, six adult children, one parent, one sibling | Cancer is only mentioned in the title. It is unclear whether all interviews took place while the patient was still alive or not. | Yes | 6 |

| Milberg and Strang 28 | Sweden, Europe | To describe aspects that, from the family members’ perspective, are experienced as protective against perceptions of powerlessness and/or helplessness or as helpful when coping with such experiences during palliative home care. | Manifest qualitative content analysis | 233 (148 women, 84 men, 1?) | 31–91 years (mean 71) | 157 spouses or live-partners, 51 children, 11 siblings, five parents, eight other, and one unknown | Patients diagnosed with cancer (lung, gastro-intestinal, prostate, liver, pancreas, breast, brain, other). | No | 5, 6 |

| Sjolander et al. 29 | Sweden, Europe | To explore management strategies that family members use when the patient is in the early stage of treatment for advanced cancer. | Latent content analysis | 20 (16 women, four men) | 31–77 years (mean 60) | Family members (11 partners, two cohabitants, five adult children, one uncle, one ex-partner) | Patients recently (8–14 weeks earlier) diagnosed with advanced lung or gastrointestinal cancer. | No | 6 |

| Mosher et al. 30 | Indianapolis, USA, America | To identify advanced, symptomatic lung cancer patients’ and caregivers’ strategies for coping with various physical and psychological symptoms. | Theoretical thematic analysis framed by stress and coping theory | 21 patients and 21 caregivers | Patients: 39–80 (mean 63), Caregivers 38–78 (mean 58) | Patients and caregivers. Twele spouses/partners, four adult children, five siblings | Lung cancer patients with significant pain, fatigue, breathlessness, anxiety, or depressive symptoms. | No | None |

| Engeli et al. 31 | Switzerland, Europe | To analyze resilience as per Antonowsky’s sense of coherence. To identify differences and changes in resilience 6 months after the first interview. | Content analysis | eight patients and eight partners | Patients 44–75 years, Partners 46–82 years | Patients and partners | Patients recently diagnosed with advanced malignant melanoma. | No | 6 |

| Mosher et al. 32 | Indianapolis, USA, America | To identify positive changes in patients with advanced colorectal cancer and their primary family caregivers since the diagnosis. | Thematic analysis | 23 patients (9 women, 14 men), 23 caregivers (20 women, three men) | Patients: 40–82 (mean 58), Caregivers 35–76 (mean 56) | Patients and their family caregiver (18 spouses/partners, five other family members). | Patients diagnosed 8 weeks prior with advanced (stage III or IV) colorectal cancer. | No | None |

| Sparla et al. 33 | Germany, Europe | To explore and compare reflections that arise out of the context of diagnosis and to compare how patients and their relatives try to handle advanced lung cancer. | Qualitative content analysis with deductive and inductive approach | 18 (nine patients (three women, six men), nine relatives (six women, three men) | Patients 55–79 years (mean 63), Relatives 51–66 (mean 54) | Patients and their relatives. Six spouses. | Patients with lung cancer stage 4 | No | 6 |

| Walshe et al. 11 | North west of England, Europe | To understand successful strategies used by people to cope well when living with advanced cancer; To explore how professionals can support effective coping strategies; To understand how to support development of effective coping strategies for patients and family caregivers. | Constant comparison | 50 (26 patients, 24 caregivers) | Patients 32–82 years (mean 56.9), caregivers 28–74 (mean 52.5) | People with advanced cancer and their family caregivers (17 spouses, four children, two parents, one sibling). | Patients diagnosed with advanced cancer (breast, prostate, lung, colorectal, other). | No | None |

| Roen et al. 34 | Norway, Europe | To explore factors promoting caregiver resilience, based on caregivers’ experiences with and preferences for healthcare provider support. | Systematic text condensation | 14 (seven women, seven men) | Mean age 59 years | Family caregivers of advanced cancer patients (12 partners, two children) | Patients diagnosed with advanced cancer (breast, colon, gallbladder, kidney, lymph, pancreas, prostate, skin) and enrolled in a palliative care program. | No | 6 |

| Opsomer et al. 35 | Flanders, Belgium, Europe | To explore what intrinsic and extrinsic resources facilitate or hamper resilience in the middle-aged partner of a patient with incurable cancer. | Thematic analysis | 9 (six women, three men) | 42–58 years (mean 54) | Partners of cancer patients. | The patients died of cancer (colon, skin, breast, glioblastoma, pancreatic) less than 12 months before the interview. | No | None |

Critical appraisal: criteria: (1) Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

(2) Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?

(3) Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

(4) Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

(5) Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

(6) Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?

(7) Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?

(8) Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

All studies, including the papers that did not meet all quality appraisal criteria, were considered relevant for our synthesis. Most studies met seven or more of nine criteria. The two studies of lower quality underpinned the findings of the other studies but did not reveal new information. As a result, they did not affect the final synthesis results.

Data collection process

Data extraction

Data on study methodology, the researched population, and the aim of the original study were mapped and are presented along with the outcomes of the critical appraisal in Table 1.

Data synthesis and analysis

All findings from the primary studies were listed and coded line by line. The codes were inserted as first level codes in NVivo 1.3 and provided with the accompanying quotes and fragments. Consequently, the codes were organized deductively according to the four elements of resilience as described in Bonanno et al.’s 13 theoretical framework. Within those four elements, the codes were organized inductively into descriptive themes and subthemes. The codes that did not fit into Bonanno et al.’s 13 framework were further mapped inductively into new themes and concepts.

After re-reading the included manuscripts, the resulting code tree was discussed repeatedly within the team of authors until consensus was reached. The final code tree, illustrated by quotes, is provided as Supplemental Material S2.

Synthesis of findings

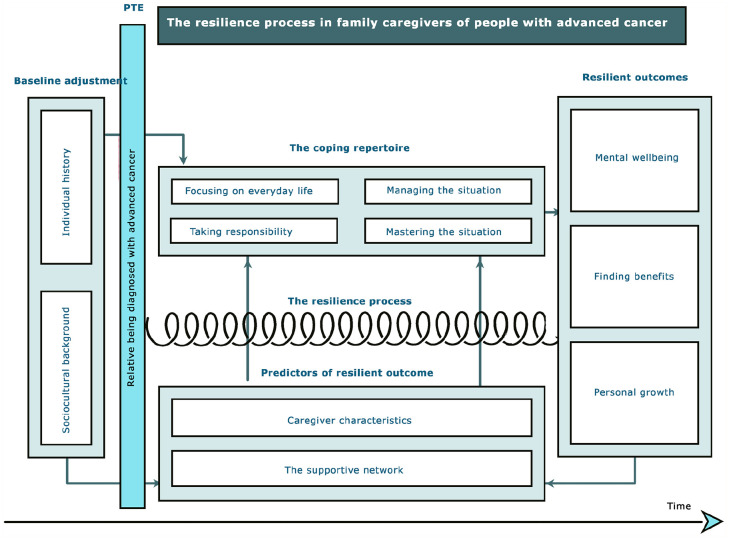

The four elements of resilience as defined by Bonanno et al. 13 (the potentially traumatic event, baseline adjustment, resilience predictors, and resilient outcome) were represented in the original manuscripts. However, some codes did not match the pre-defined framework. All codes were verbs and could be clustered as a repertoire of coping strategies the caregivers used throughout the caregiving process. A graphic representation of the findings is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Graphic representation of the findings.

The potentially traumatic event

The primary potentially traumatic event, namely a family member being diagnosed with advanced cancer, was part of the inclusion criteria. Subsequent events (e.g. hospital admissions, confrontation with physical changes, being diagnosed with new metastases), were considered a component of the primary traumatic event. Following the diagnosis, the caregiver’s world takes on a surreal character. This period is characterized by intense emotions, critical events, and the predominance of the gravely ill relative.21,25 The uncertainty of prognosis and the consciousness of the person moving toward death threatens the caregiver’s mental wellbeing. 20 Nevertheless, this period of mental disturbance is followed by adaptation to the new situation and the start of a resilience process.11,20–35

Baseline adjustment

Baseline adjustment refers to how people functioned prior to the potentially traumatic event and to their psychological adjustment to other challenges in life. 13 Both the caregiver’s individual history (outlook on life, spirituality or religious inspiration, previous roles in life, past experiences of loss, etc.) 23 and sociocultural background can have an influence on how caregivers will adapt to the subsequent adversity of having a family member being diagnosed with advanced cancer). 26

If something needs doing, you just go do it. You don’t sit around and whine about it. Whining gets you nowhere in life. That’s always been the way I’ve been, and I guess that’s how I’m coping [with caregiving at home] (p. 80). 23

In our family we have never been open about death, we have rather joked about it (p. 1121). 26

Predictors of resilient outcomes

Context-dependent and subsequent changing variables such as personal characteristics and one’s supportive network are associated with individual resilient outcomes. 13

Caregiver characteristics

Although no single characteristic can guarantee a resilience process, caregivers seem more likely to attempt a positive outcome when they develop one or more of the following characteristics:

Balanced dependency23,35 involves a mutual give and take between caregivers and those on whom they can trust and rely. Here, both parties give and receive support, encouragement, and practical help. This can be best illustrated by the following quote:

I then called on someone we know well, a good friend, whose wife also died at home, after the whole process at home and, by chance, the same GP. I called him asking, should I do that? Am I able to do that? Because, like, you’re afraid of that too, right. How is this all gonna go? And the dying, how’s that gonna go and will I be able to handle that? There are so many questions going through your head (p. 12). 35

Flexibility , or the capacity to adapt accordingly to changing circumstances. Flexibility is a characteristic that can be expressed by taking up a new role, adapting one’s lifestyle, or seeking out distracting activities. 35

I went there in agony with him. But I did it (. . .) And there, in that foreign country, with those techniques. Because they didn’t know the technique of draining the fluid, they taught me how to do it in the hospital, so I could do it myself. And uhm, I did do it, but it was so difficult because I was in a different role there. In the end, I really was his nurse. (. . .) Then we drove back home. I had never driven that long myself. I didn’t even like to drive with his car because it was so big. Actually, I don’t like to drive at all. But I didn’t have a choice back then. So, I had to overcome several fears, but in such a situation, you just do it (p. 12). 35

Positive attitude , a characteristic that is often fueled by humor and irony. This assists people in discovering a solution to their problems, attaching positive meaning to the crisis, and in finding benefits in it. Positivity can be expressed by the caregiver’s attempts to fulfill the patient’s wishes or by sustaining a sense of hope.26,33,35

Actually, how something so horrible [as his partner who was dying from cancer] can bring up such beautiful things. Yes, that’s just it. It was horrible and it still is, but. . . In the end, it was something beautiful, especially the moment she told me she had been happy. That gave me such a satisfied feeling (p. 13). 35

Information processing , a characteristic that is reflected in the complex and fragile balance between incoming and outgoing information regarding the cancer. Knowledge about the illness, prognosis, and technical aspects of caregiving gained from healthcare professionals, the literature available, and the Internet is reported to have been helpful. Nevertheless, information gathered through one’s own previous experiences or from peers—mostly based on lived experiences or ‘learning the hard way’—and focusing on the everyday aspects of living with cancer is described as even more supporting and empowering.11,28,34,35 Furthermore, the information people want to receive does not always mirror the information they want to share with others. Most caregivers do not feel the need to discuss the person’s cancer and are concerned about how to inform others about the illness.11,31 The caregiver, as information processor, is illustrated by the following quote:

I think we have found a good way to deal with the situation. People sometimes ask how my wife is doing, and I then tell them what is going on with her cancer at that time. But after that, we have lots of other things to talk about, and I like that. I do not want her to be seen only as a sick person (p. 128). 31

Internal strength , which may be expressed, for example, as an increase in self-confidence, leads to a heightened ability to make decisions and solve problems that facilitate a renewal of commitment to the dying family member.21,23 Self-confidence in the caregiving role can be described as protection against powerlessness and helplessness.

I felt I had a lot of strength and I needed it all, that’s for sure (p. 109). 21

I kept telling myself, ‘‘I can’t, I can’t, I can’t’’ [do the work associated with caregiving]. And everyday, I’d get up and I’d go, ‘‘I can’t.’’ The next day, I’d go to bed at night and say, ‘‘Yes you can.’’ Tomorrow is a new day. You’ve got to get up. Change your attitude. Get outside

where you are, in that darkest place (p. 80). 23

The supportive network

In addition to personal characteristics, a supportive network is essential in achieving a resilient outcome throughout the caregiving process. On the other hand, a supportive network is not always referred to as resilience facilitating. In fact, the caregiver’s network could also be resilience inhibiting.11,21–23,26,28,30,32,34,35

Meaningful relationships

Most caregivers are reinforced when surrounded by people who care about them and with whom they can share their emotions.20,28,31,35 Equally, caregivers appreciate family members and friends giving practical advice or even taking over time- and energy-consuming tasks.21,28,35 Caregivers also express their appreciation for the availability of regular visits from healthcare professionals.28,35 In spite of this, few caregivers actually take advantage of these invaluable resources offered beyond office hours.21,28,31,34,35 On the other hand, family caregivers feel empowered by healthcare professionals and friends who take the time to proactively assess their needs.28,34,35

I was privileged during the difficult period. My sister and brother-in-law were here all the time and helped my husband and me. My husband did not have to be alone in his room, and I could take a break, that was a great help for me (p. 255). 26

The patient’s contribution to the caregiver’s wellbeing should not be underestimated. Frequently, the patient’s physical and mental condition is an important predictor of the caregiver’s resilient outcome.31,35 Feelings of satisfaction and accomplishment are related to the patient’s characteristics or behavior. Those feelings result from caring for patients who are positively minded or patients who accept their illness and impending death without complaining. Caregiving may become a resilient process when patients respect the caregiver’s needs or spiritual beliefs, express their feelings of gratitude, and let the caregiver know that they can reflect on a happy life.21,23,28,34,35 If the patient and the caregiver are life partners, the quality of their relationship can influence the resilient outcome even further; mutual love, trust, togetherness, and respect are reported as important facilitators for caring.23,24,27,34,35

I went along with her positivity. Because when your partner is so positive, you’re not going to tell her that it may only last six months or . . . No, then you just pull away the belief, you pull away all the hope from under her feet. You simply don’t do that (p. 17). 35

A coping repertoire

Within the coping repertoire, four different coping strategies could be identified: focusing on everyday life, taking responsibility, managing, and mastering the situation.

Focusing on everyday life

The unpredictability of the cancer provides caregivers no other options than to “take it one day at a time.”29,31,33 Some caregivers avoid the reality as if the cancer does not exist and death is far off in the future.23,25,26,29,31,33 They strive to continue a normal existence by taking part in everyday activities or by maintaining their usual work schedule.11,34 The structure of everyday life symbolizes life itself. 27 Hence, focusing on the present keeps hope alive and supports a sense of peace and meaningfulness.27,29 This means of coping allow the caregiver to treat the patient as a living human being instead of a dying one. 26 This “normality” can offer caregivers an escape from the cancer and give them the chance to renew their energy level and to maintain a sense of wellbeing despite the stressful situation.11,26,28,29,31,33–35

Things just go on like before. We talk, we putter around here, we clean a bit and help each other and nothing is so different when it comes to all that (. . .). We used to work at the same place, and we have our ways (laughs) And she bakes something sometimes, a cake or buns or something, which we can have if we want. No, it works quite well. (. . .) We go on more or less as usual so it’s all right (p. 71). 27

Taking responsibility

Caregivers feel not only responsible for the physical and mental wellbeing of the patient, but also for their own welfare and that of family and friends.25,29,32 While some caregivers feel compelled to assume the caregiving role, others feel it a natural response. 27 In a similar vein, caregivers find satisfaction in meeting the expressed needs of the patient, 25 in accepting new roles, or in taking over tasks the patient used to fulfill.33,35

. . . then you get talking to other people and they help their mums out a couple of days a week and things like that, but I don’t. . . you feel bad if you don’t go up there and you feel bad when you are there (p. 73). 27

Caregivers sometimes minimize the details of the cancer. In this manner, they try to shield their family members and friends from grief by making them believe everything will turn out all right. 29

Some caregivers realize that they should not only take responsibility for the patient and their families, but also for their own wellbeing. As a result, they start to eat healthier, increase their activity level, and schedule more frequent preventive medical checkups. 32

Managing the situation

Caregivers who manage the situation intend to control or alter the situation through the use of situation-corrective actions

Firstly, a sense of control over the cancer can result from insight into the disease and therapy. Therefore, caregivers gather information about the cancer by talking to healthcare professionals and peers or by searching the Internet.26,28,31 Secondly, caregivers continue to hope that the cancer will disappear or go into remission. They focus on the symptoms instead of the cancer since the former can be treated. In that way, alleviating the symptoms provides a sense of control.26,29,35 Thirdly, some caregivers work toward specific goals to control the situation. For instance, they may do their all to keep the patient out of the hospital or attempt to prolong the patient’s life by intervening in the therapy. Trying new, or even alternative treatments, contributes to a level of hope in extending the patient’s life.26,35

I knew it was available in a neighboring country, so I e-mailed the firm and called the local representative in advance to inquire which doctors had contributed to the study, and so on. Then, I contacted them. I received e-mail addresses, and we got accepted abroad (p. 8). 35

Mastering the situation

Caregivers who master the situation accept the cancer and the idea that the patient will die. They flexibly adjust their lifestyles to the situation. Sometimes, a cocoon-like situation is created with the predominance of the dying family member whose comfort and quality of life should be guaranteed. This may be achieved by maintaining a sense of peace and serenity or by fulfilling the patient’s last wishes.21,35 Being surrounded by family becomes increasingly important. 29 Lifestyle is adjusted to the patient’s needs and wishes. Daily planning is adapted to the patient’s condition, often at the expense of the caregiver’s own social activities.29,35 The caregivers organize pleasant activities for the patient by creating moments to cherish. Indulgences are embraced and mostly involve activities the patient used to enjoy before diagnosis.11,28,35 Caregivers mastering the situation deal with the cancer in a realistic way which prevents frustration and disappointment that go with unachievable goals and which enhances their wellbeing. 11 The caregivers strive to be prepared for the emotional pain by facing their fears for the future. Life’s priorities are reassessed whereas relationships with family and friends are often prioritized over other aspects of life.11,32 Accepting the situation often comes with uncovering meaning in the cancer, whether or not in a spiritual way, 28 and by focusing on the positive aspects of the cancer experience.11,24

[We] realize that life is precious, and our moments with people are precious. And that that is so much more important than all the little trivial, busy things of life (p. 7). 32

Resilient outcomes

Resilient outcomes are referenced to any mental condition prior to the potentially traumatic event. 13 As such, resilient outcomes could be described as stability in mental functioning, finding benefits in caregiving, or in personal growth.11,22,24,25,27,32,35

Some caregivers reported that coping with the cancer diagnosis helped them to maintain mental wellbeing; they could continue to be themselves and felt like ordinary members of society.11,20,29,32

But as far as physical changes or mental changes relative to dealing with cancer, I can’t say that I’ve noticed much change in the way my wife or I approach life (p. 8). 32

Other participants experienced benefits of caregiving both in a sense of reward and through deepened relationships.22,25,32 A sense of reward can result from the meaning family members find in caregiving or can be associated with a “feel good” death, meaning that the patient died peacefully, surrounded by family and at the place which they preferred. Furthermore, caregiving can profoundly and positively change relationships, leading to a sense of togetherness and more intense relationships both with the patient and with other family members.22,27,32,35 Through caregiving, relationships are often prioritized over other life domains. 32 Some caregivers mentioned a greater sense of closeness to or an enhanced trust in God. 32

Yes, I suppose to some extent it was rewarding for me because I could do it and it meant that it kept her out of hospital (p. 277). 25

Some stories go even further and reflect the personal growth that the participants experienced—a personal growth that was expressed in different ways. For instance, caregivers felt stronger by being immersed in adversity, and hence being forced to face not only their fears and shortcomings, but also their strengths.22,24,27 Moreover, an increased empathic ability and enhanced connection with others was reported.24,27,32 Furthermore, from the awareness of shortness of life, a greater appreciation of life and of time with loved ones can arise.24,32

We’ve learned a lot of patience and tolerance for other people that we didn’t have before, a lot more empathy that we have for people who have adversity whether it’s cancer or any other kind of problem. . . you feel a connection and an empathy for that, that we didn’t have before (p. 8). 32

Discussion

Main findings

This meta-synthesis aims to synthesize the findings of qualitative studies on resilience in cancer caregiving based on the theoretical framework of Bonanno et al. 13 as suggested by Opsomer et al. 6 The four elements of resilience, as defined by Bonanno et al. 13 in their theoretical framework, are reflected in the lived experiences of family caregivers. A family member or friend being diagnosed with incurable cancer can be considered a potentially traumatic event 6 and a prospective starting point of a resilience process 13 that leads to three patterns of resilient outcomes, namely mental wellbeing, benefit finding, or personal growth. The resilience process itself is influenced by different contextual factors related to: (1) the caregiver’s baseline adjustment, determined by the person’s individual history and the sociocultural background, and (2) a number of evolving and interacting resilience predictors. These characteristics and abilities include balanced dependency, being flexible, and serving as information processor. Additionally, the caregiver is charged with being positive, injecting humor, and maintaining an inner strength. The caregiver can also best be supported by a network of family (including the patient themselves), friends, and healthcare professionals who provide practical and emotional support. Although most of our findings fall within the theoretical framework of Bonanno et al. 13 a complementary theme highlighting the repertoire of coping strategies used during the resilience process came to the fore, namely: focusing on everyday life, assuming responsibility, and managing and mastering the situation. These coping strategies could potentially be moderators in the resilience process, on the one hand between the baseline adjustments and resilience predictors and the resilience outcomes on the other. 37

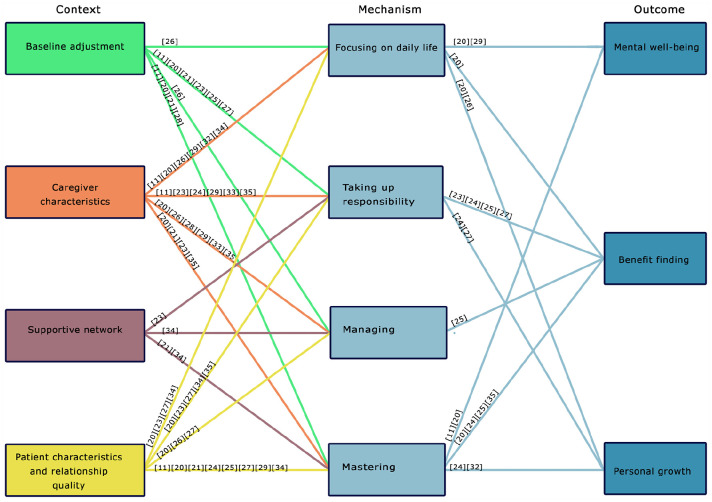

Approaching the coping strategies as moderators of the resilient process may enhance the insight into the underlying mechanisms of the resilience process and provide an answer to the question: Why is a cancer diagnosis followed by a resilience process and a resilient outcome in one family caregiver and not in the other? Such questions are typically answered by realist research, a philosophy-driven approach developed by Pawson and Tilley. 37 Indeed, scientific realism does aim to identify mechanisms in order to explain what works, for whom, why, how, and in what contexts.37,38 Our findings might be complemented and extended by approaching them in a realist way. 39 A realist context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configuration may lead to explanations of the observed outcomes and may be the basis for refining an existing theory. The context is defined as all resources that facilitate, influence, or moderate the outcome. The mechanisms are the underlying processes triggered by the particular context to generate outcomes which are the different effect patterns discovered in the data. 40 Those outcomes can change the resources, and as such become a new context factor that generates other mechanisms, and thus creates new outcomes. 39 This is illustrated by a hypothetical example stemming from our findings (see Supplemental Material S4). Such a realist approach may possibly reveal whether the coping strategies that emerged in this review are the mechanisms that enable the context factors (baseline adjustment and resilience predictors) to elicit resilience outcomes. Moderated by the four coping strategies, most context factors within the themes “baseline adjustment” and “caregiver characteristics” could be linked to all resilient outcomes. Nevertheless, evidence of the association between “the supportive network characteristics” and the “coping mechanisms” is scarce.21,29,34 However, all four coping strategies are part of trajectories leading to a resilient outcome. The strategies are context-dependent, and no strategy seems to be preferable over another. Strategies like focusing on everyday life imply avoiding any confrontation with the cancer diagnosis or even denying the cancer. Those strategies are often considered emotional or negative coping. 41 Nevertheless, temporarily acting as if the cancer does not exist, can help people to enjoy the smaller things in life that otherwise would be experienced as normal. Therefore, when applied following a cancer diagnosis, focusing on daily life seems to be rather protective and supports a resilient process. From the selected studies, the coping strategies “focusing on daily life” and “mastering the situation” are linked with all three resilient outcomes, while taking up responsibility was not associated with mental wellbeing in the included studies. Surprisingly, only one study reveals a connection between “managing the situation” and the resilience outcome “benefit finding.” Hence, it is unclear if managing the situation can lead to mental wellbeing or personal growth. From our search strategy no studies oriented specifically on bouncing back to mental wellbeing could be discovered. However, mental wellbeing and healthy functioning is described as the most common resilient outcome8,42–44 and “bouncing back” is actually part of the definition of resilience. Nevertheless, three studies on benefit finding or personal growth through cancer caregiving were included.22,24,32 The lack of qualitative studies focusing on mental wellbeing as a resilient outcome in cancer caregiving could explain the vagueness of the relation between mental wellbeing and the different coping mechanisms used by caregivers. A simplified CMO scheme is presented in Figure 3. The detailed schemes are provided in Supplemental Material S5. It can be concluded that the caregiver’s baseline adjustment and individual characteristics can influence the four resilient coping strategies, which consequently are linked with resilient outcomes such as benefit finding and personal growth. This may clarify the results of earlier studies that establish a link between caregiver characteristics and positive outcome.45,46

Figure 3.

Simplified context—mechanism—outcome scheme.

Many resilience studies emphasize the importance of context support in maintaining mental wellbeing.47–49 However, in the included studies, a supportive network was designated as ambivalent resilience facilitating and resilience inhibiting.11,21–23,26,28,30,32,34,35 Moreover, the association with the coping strategies, and consequently, with the resilient outcomes, could not be elucidated sufficiently from this review. Context support is unlikely a stable resource, but rather a dynamic and complex system in which context members interact within different behavior patterns that work for some people under specific circumstances, but not for others.50,51 Using the realist CMO-lens on the behavior of the caregiver’s context as well as the influence on the resilient coping strategies is needed to clarify why, how, and for whom a supportive network can result in a resilient outcome.

Nevertheless, this review has been confirmed that Bonanno’s theoretical framework of resilience is largely applicable to the particular situation of caregivers confronted with a loved one’s diagnosis of incurable cancer. The coping strategies are not inherent to the resilience process but are a mechanism by which the context (baseline adjustment and resilience predictors) can result in a resilient outcome, which, consequently, can influence the context factors or can act as a new resilience predictor itself in the course of the resilience process following the diagnosis of advanced cancer.13,39

In order to avoid the chaos of multiple definitions and approaches of resilience, this meta-synthesis was based on an existing definition, namely the APA definition, and an established theoretical framework that were proposed in a hermeneutic review by Opsomer et al. 6 as the most suitable to study resilience in cancer caregiving.6,12,13 Consequently, in the analysis, the original findings were brought together, interpreted, analyzed, and coded again, resulting in new findings that are more general and better-grounded than the original studies’ results. 52 Moreover, as recommended by Paterson et al. 53 the quality of the synthesis could be optimized by the reflexivity and diversity of the research team, including researchers from different disciplines, with differences in research experience, diverse methodological background, and a different perspective on the studied phenomenon. However, this review has its limitations. From the start, we struggled with the variability in which resilience is approached and with the inconsistency in terminology used in the primary papers. The number of included manuscripts containing a definition of resilience is low. In one study, resilience is approached from the theoretical framework on another salutogenic concept, “sense of coherence.” 31 Some of the manuscripts were included because the investigated phenomenon met the APA definition of resilience 12 even when the manuscript itself did not mention the word “resilience.” On the other hand, a synthesis of qualitative studies was preferred above a mixed-methods synthesis since the quantitative manuscripts did not approach resilience as a process but as a trait, and thus did not meet the APA definition.

What this study adds and implications

This review may enhance insights into resilience in caregivers of patients diagnosed with advanced cancer and the role of coping strategies. These new understandings can be used in the development of resilience supporting interventions and in clinical practice. The insufficiency of focusing exclusively on how caregivers manage the situation is underlined. Moreover, our findings stress the importance of taking into account the resilience predictors (the caregiver’s characteristics and their supportive network), as well as the moderating coping strategies and the intermediate outcomes. Eventually, one should be aware of perpetual changes in context factors during the caregiving process as the intermediate outcomes may influence the resilience predictors or even serve as new context factors.

Our analysis also reveals some gaps in knowledge. Little is known about the behavioral patterns of the supportive network and the coping strategies related to these particular resilience predictors. More profound research from the realist frame on the caregiver’s supportive network would bring more clarity in this matter. Moreover, from this review, it can be assumed that the resilience process following a relative’s cancer diagnosis is iterative. However, more longitudinal research is needed to fully identify the underlying patterns.

Conclusion

Starting from an integrative process-oriented theory, this review reveals key elements of resilience in the process of cancer caregiving, including influencing factors and outcomes. Moreover, new explanations emerged on how context elements such as individual history, sociocultural background, the caregiver’s characteristics, and the behavior of their supportive network, are all moderated by coping strategies to reach a resilient outcome. Furthermore, some gaps in knowledge on the behavior patterns of the supportive network and on the successive interactions within the resilient process are highlighted.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-5-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-6-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Mrs. Magdalena Jans for her assistance with drawing up the search strings, Dr. Curt Dunagan for his proofreading and language editing of the manuscript, and the University Foundation of Belgium (Universitaire Stichting van België) for supporting this publication.

Footnotes

Authorship: All authors made a substantial contribution to the concept or design of the review or to the selection and analysis of the data. They all took part in writing or revising. They all approved the final version. All authors can take public responsibility for the content of the review. A detailed overview of each author’s contribution is provided in Supplemental Material S6.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Sophie Opsomer  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8956-5678

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8956-5678

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Bell CL, Somogyi-Zalud E, Masaki KH. Factors associated with congruence between preferred and actual place of death. J Pain Symptom Manag 2010; 39: 591–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gomes B, Calanzani N, Higginson IJ. Reversal of the British trends in place of death: time series analysis 2004-2010. Palliat Med 2012; 26: 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Being a caregiver. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/caregiving/being-a-caregiver (2021, accessed 4 August 2021).

- 4. Park B, Kim SY, Shin JY, et al. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression among family caregivers of cancer patients: a nationwide survey of patient-family caregiver dyads in Korea. Support Care Cancer 2013; 21: 2799–2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Trevino KM, Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK. Advanced cancer caregiving as a risk for major depressive episodes and generalized anxiety disorder. Psychooncology 2018; 27: 243–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Opsomer S, De Lepeleire J, Lauwerier E, et al. Resilience in family caregivers of patients diagnosed with advanced cancer - unravelling the process of bouncing back from difficult experiences, a hermeneutic review. Eur J Gen Pract 2020; 26: 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol 2004; 59: 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Galatzer-Levy IR, Huang SH, Bonanno GA. Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: a review and statistical evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 2018; 63: 41–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O’Rourke N, Kupferschmidt AL, Claxton A, et al. Psychological resilience predicts depressive symptoms among spouses of persons with Alzheimer disease over time. Aging Ment Health 2010; 14: 984–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anyan F, Worsley L, Hjemdal O. Anxiety symptoms mediate the relationship between exposure to stressful negative life events and depressive symptoms: a conditional process modelling of the protective effects of resilience. Asian J Psychiatr 2017; 29: 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Walshe C, Roberts D, Appleton L, et al. Coping well with advanced cancer: a serial qualitative interview study with patients and family carers. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0169071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Psychological Association. APA: the road to resilience. https://www.uis.edu/counselingcenter/wp-content/uploads/sites/87/2013/04/the_road_to_resilience.pdf (2020, accessed 10 September 2021).

- 13. Bonanno GA, Romero SA, Klein SI. The temporal elements of psychological resilience: an integrative framework for the study of individuals, families, and communities. Psychol Inq 2015; 26: 139–169. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Siddaway AP, Wood AM, Hedges LV. How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol 2019; 70: 747–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012; 12(1): 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paterson B, Thorne S, Canam C, et al. Meta-Study of qualitative health research: a practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. London: SAGE, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grudniewicz A, Moher D, Cobey KD, et al. Predatory journals: no definition, no defence. Nature 2019; 576: 210–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016; 5: 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rose KE, Webb C, Waters K. Coping strategies employed by informal carers of terminally ill cancer patients. J Cancer Nurs 1997; 1: 126–133. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Strang VR, Koop PM. Factors which influence coping: home-based family caregiving of persons with advanced cancer. J Palliat Care 2003; 19: 107–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hudson P. Positive aspects and challenges associated with caring for a dying relative at home. Int J Palliat Nurs 2004; 10: 58–65; discussion 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stajduhar KI, Martin WL, Barwich D, et al. Factors influencing family caregivers’ ability to cope with providing end-of-life cancer care at home. Cancer Nurs 2008; 31: 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wong WK, Ussher J, Perz J. Strength through adversity: bereaved cancer carers’ accounts of rewards and personal growth from caring. Palliat Support Care 2009; 7: 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wong WK, Ussher J. Bereaved informal cancer carers making sense of their palliative care experiences at home. Health Soc Care Community 2009; 17: 274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Benkel I, Wijk H, Molander U. Using coping strategies is not denial: helping loved ones adjust to living with a patient with a palliative diagnosis. J Palliat Med 2010; 13: 1119–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sand L, Olsson M, Strang P. What are motives of family members who take responsibility in palliative cancer care? Mortality 2010; 15: 64–80. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Milberg A, Strang P. Protection against perceptions of powerlessness and helplessness during palliative care: the family members’ perspective. Palliat Support Care 2011; 9: 251–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sjolander C, Hedberg B, Ahlstrom G. Striving to be prepared for the painful: management strategies following a family member’s diagnosis of advanced cancer. BMC Nurs 2011; 10: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mosher CE, Ott MA, Hanna N, et al. Coping with physical and psychological symptoms: a qualitative study of advanced lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. Support Care Cancer 2015; 23: 2053–2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Engeli L, Moergeli H, Binder M, et al. Resilience in patients and spouses faced with malignant melanoma. A qualitative longitudinal study. Eur J Cancer Care 2016; 25(1): 122–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mosher CE, Adams RN, Helft PR, et al. Positive changes among patients with advanced colorectal cancer and their family caregivers: a qualitative analysis. Psychol Health 2017; 32: 94–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sparla A, Flach-Vorgang S, Villalobos M, et al. Reflection of illness and strategies for handling advanced lung cancer: a qualitative analysis in patients and their relatives. BMC Health Serv Res 2017; 17: 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Røen I, Stifoss-Hanssen H, Grande G, et al. Resilience for family carers of advanced cancer patients-how can health care providers contribute? A qualitative interview study with carers. Palliat Med 2018; 32: 1410–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Opsomer S, Pype P, Lauwerier E, et al. Resilience in middle-aged partners of patients diagnosed with incurable cancer: a thematic analysis. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0221096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res Methods Med Health Sci 2020; 1(1): 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: SAGE Publications Inc, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marchal B, Van Belle S, Westhorp G. Realist evaluation. https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/approach/realist_evaluation. (2017, accessed 20 February 2021).

- 39. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. Realist methods in medical education research: what are they and what can they contribute? Med Educ 2012; 46: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Flynn R, Rotter T, Hartfield D, et al. A realist evaluation to identify contexts and mechanisms that enabled and hindered implementation and had an effect on sustainability of a lean intervention in pediatric healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res 2019; 19: 912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Paek MS, Ip EH, Levine B, et al. Longitudinal reciprocal relationships between quality of life and coping strategies among women with breast cancer. Ann Behav Med 2016; 50: 775–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ayed N, Toner S, Priebe S. Conceptualizing resilience in adult mental health literature: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Psychol Psychother 2019; 92: 299–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cosco TD, Kaushal A, Hardy R, et al. Operationalising resilience in longitudinal studies: a systematic review of methodological approaches. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017; 71: 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bonanno GA. Uses and abuses of the resilience construct: loss, trauma, and health-related adversities. Soc Sci Med 2012; 74: 753–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Semiatin AM, O’Connor MK. The relationship between self-efficacy and positive aspects of caregiving in Alzheimer’s disease caregivers. Aging Ment Health 2012; 16: 683–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li Q, Loke AY. The positive aspects of caregiving for cancer patients: a critical review of the literature and directions for future research. Psychooncology 2013; 22: 2399–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kotkamp-Mothes N, Slawinsky D, Hindermann S, et al. Coping and psychological well being in families of elderly cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2005; 55: 213–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nicholls W, Hulbert-Williams N, Bramwell R. The role of relationship attachment in psychological adjustment to cancer in patients and caregivers: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology 2014; 23(10): 1083–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Triemstra M, et al. The role of social and psychologic resources in caregiving of cancer patients. Cancer 2001; 91: 1029–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pype P, Krystallidou D, Deveugele M, et al. Healthcare teams as complex adaptive systems: focus on interpersonal interaction. Patient Educ Couns 2017; 100: 2028–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pype P, Mertens F, Helewaut F, et al. Healthcare teams as complex adaptive systems: understanding team behaviour through team members’ perception of interpersonal interaction. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18: 570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Leary H, Walker A. Meta-analysis and meta-synthesis methodologies: rigorously piecing together research. TechTrends 2018; 62: 525–534. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Paterson BL, Dubouloz CJ, Chevrier J, et al. Conducting qualitative metasynthesis research: insights from a metasynthesis project. Int J Qual Methods 2009; 8: 22–33. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-5-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-6-pmj-10.1177_02692163211057749 for Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis by Sophie Opsomer, Emelien Lauwerier, Jan De Lepeleire and Peter Pype in Palliative Medicine