Abstract

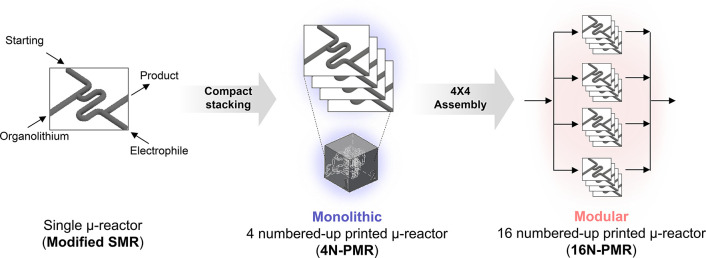

Continuous-flow microreactors enable ultrafast chemistry; however, their small capacity restricts industrial-level productivity of pharmaceutical compounds. In this work, scale-up subsecond synthesis of drug scaffolds was achieved via a 16 numbered-up printed metal microreactor (16N-PMR) assembly to render high productivity up to 20 g for 10 min operation. Initially, ultrafast synthetic chemistry of unstable lithiated intermediates in the halogen–lithium exchange reactions of three aryl halides and subsequent reactions with diverse electrophiles were carried out using a single microreactor (SMR). Larger production of the ultrafast synthesis was achieved by devising a monolithic module of 4 numbered-up 3D-printed metal microreactor (4N-PMR) that was integrated by laminating four SMRs and four bifurcation flow distributors in a compact manner. Eventually, the 16N-PMR system for the scalable subsecond synthesis of three drug scaffolds was assembled by stacking four monolithic modules of 4N-PMRs.

Short abstract

A compact numbered-up metal microreactor affords high productivity of three drug scaffolds up to 20 g for 10 min via subsecond synthesis of unstable aryllithium intermediates.

Introduction

Synthetic chemistry relies on interactions between reactive species. However, an unstable reactive intermediate often changes shape while waiting for another reactant, resulting in an undesired outcome. In general, lithiation/organolithium reactions play a significant and vital role in active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) synthesis. However, these highly reactive chemistries are difficult to handle in conventional batch reactors because of their enormous reactivity, pyrophoric nature, and vulnerability to environmental air/oxygen or moisture. Alternatively, flow technologies and microstructured devices are promising key tools for lithiation/organolithium reactions because of their rapid mass and heat transfer and high surface-to-volume ratios.1−15 Notably, microreactors have attracted great attention in the field of organic chemistry owing to their empowerment in ultrafast synthesis, which utilizes highly reactive short-lived intermediates through precise residence time control.16,17 The ultrafast synthesis enables the handling of unstable and short-lived intermediates generated by the halogen–lithium exchange reaction to provide direct and efficient synthetic routes for target compounds,18−22 rendering improved selectivity and yield compared to batch processes.23−28 Moreover, small reaction volumes and high flow rates, which are inevitable for short residence times, as well as high mixing efficiencies also contribute to high productivity.19,29 Therefore, an ultrafast synthetic methodology would be a huge breakthrough in overcoming the inherent productivity constraints of conventional flow chemistry caused by their capacities.

Highly sophisticated microreactors have been designed and fabricated to continuously reduce the mixing time scale in the flow along the microchannel, thereby improving the control performance of unstable intermediates.18 In 2016, a single-chip microreactor (CMR) with rectangular cross-sectional channels (250 μm × 125 μm) was developed by our group to realize submillisecond residence times by laminating multiple polymer film patterns. The CMR devised with excellent mixing efficiency allowed outpacing of an intramolecular Fries rearrangement of an unstable aryllithium intermediate to produce the desired products.30 Alternatively, a 3D-printed stainless steel metal microreactor with a circular channel (Ø = 170 μm) was fabricated using the selective laser melting (SLM) method, enhancing the yield of identical intramolecular rearrangement reactions from 73% to 85%, by virtue of superior mixing efficiency in the absence of dead volume.31 These previous studies demonstrated efficient ultrafast chemistry in microreactors with different manufacturing methods. However, the small-scale single-channel capacity did not meet the industrial-level productivity of target compounds despite the improved yield.32

A simple size-up approach to increase the inner volume of a single reactor with a larger diameter microchannel produced lower mixing efficiency, which requires incorporation of unique types of extra mixers for ultrafast chemistry, as reported.33−35 However, it is still problematic to manage the pressure drop issue at high flow rates in the extended length of a reactor for achieving a large scale of production.36 Therefore, the numbering-up strategy of aligning multiple microreactors in parallel or in a stack is considered to be the most effective for increasing the overall throughput.37−41 For numbering-up microreactors to carry out effective ultrafast chemistry, an advanced approach is required to devise a simple design of a microreactor with excellent mixing efficiency, instead of the complex and nonplanar channel structures that make it difficult to manufacture a laminated structure. Furthermore, it is essential to evenly feed the reagents into the laminated microreactors to ensure equivalent ultrafast synthesis under the optimized conditions. Therefore, the elaborate design of flow distributors under extreme spatial and temporal restrictions is a major challenge. For the scale-up of ultrafast synthesis, it is important that both flow distributors and laminated reactors are geometrically integrated and precisely manufactured into a confined monolithic structure.

In this context, we present a new cascading scale-up strategy for ultrafast subsecond synthesis via lithiated intermediates using a monolithic 3D-printed metal microreactor embedded with built-in flow distributors, further assembling the monolithic reactors with external flow distributors (EFDs) to produce various aryl-based drug scaffolds on a large scale of gram per minute, as shown in Scheme 1. The successful control of the short-lived intermediates was verified at the optimal residence time (∼16 ms) at a flow rate of 7.5 mL min–1. Notably, the potential applicability of aryllithium chemistry is well-documented in pharmaceutical synthesis, such as antiplatelet active compounds,19 breast cancer medicine letrozole,24,42 and benzoquinone ansamycin antibiotic macbecin I,23 under different conditions.

Scheme 1. Scale-up Strategy of Ultrafast Subsecond Flow Synthesis Using 4 Numbered-up Printed μ-Reactors (4N-PMRs) and Their Assembly to a 16N-PMR.

Results and Discussion

First, ultrafast chemistry involving highly reactive aryllithium intermediates, and generated by halogen-lithium exchange of aryl halides, was investigated in a single microreactor (SMR) as a conventional capillary reactor (40 mm long R1 part, 250 μm inner diameter) to confirm the synthetic feasibility of the drug scaffolds (see the details in Figure S1). Hereafter, a 4-fold increase in productivity was demonstrated by a 4 numbered-up 3D-printed metal microreactor (4N-PMR) that was fabricated as a compact monolithic structure incorporating four single reactors and four flow distributors by the high-resolution SLM method. Eventually, a 16 numbered-up printed metal microreactor (16N-PMR) module was assembled with four 4N-PMRs and four EFDs to improve the production scale. Using the 16N-PMR, three drug scaffolds, including bis(4-cyanophenyl) methanol as a letrozole precursor, were produced at a throughput of 1–2 g min–1, which is nearly 16 times the productivity of the SMR. From a medicinal chemical perspective, this work is promising and is a step forward in meeting the industrial needs for the efficient production of biologically active compounds from aryl halides functionalized with isothiocyanate,19 cyano,24 and nitro23 groups.

In this work, the compact 4N-PMR was configured with a seamless and interconnected array of four SMRs and multiple distributor channels, which was designed to become a built-in monolithic structure (Figure 1b; see the details in Figure S3). Three sets of the built-in bifurcation type of flow distributors can uniformly provide three reagents into four SMRs without extra components, and all reaction mixtures can collectively flow into a single outlet. In an attempt to construct a monolithic system with a high-resolution 3D printing technique for upscaling the synthetic productivity, the fabrication of complex fluidic structures with different functions is time-consuming and costly, and the probability of failure exponentially increases owing to accumulated errors in the long repetition process. With a closer look, although the planar channel geometry of the SMR would facilitate numbering-up the microreactors in a compact manner, the straight R1 channel part (40 mm long, 250 μm diameter) would be further reduced to a serpentine channel as a more space-saving design. Once the R1 part of the SMR was modified to become a serpentine channel 10 mm long and 500 μm in diameter, the acceptable variation in mixing efficiency was confirmed by computational fluid dynamics (CFD) (Figure 1a). The simulated results revealed that the modified SMR exhibited 99% mixing efficiency upon >5 ms of residence time, similar to that of the capillary type of SMR (see the details in Table S1), whereas the pressure drop of the modified SMR was significantly lowered by 28 times under the same flow conditions due to the larger diameter (see the details in Figure S2). Note that the circular cross-sectional channel shape generated outstanding mixing efficiency without complex microstructures, unlike the rectangular cross-sectional channel, which comprised dead volume at the corners.31 Therefore, the modified SMR must enable the complete generation of an aryllithium intermediate within 16 ms, as it predominantly maintains the fluidic behavior of the capillary type of SMR.

Figure 1.

Design concept and fabrication of the 4 numbered-up printed metal microreactor (4N-PMR). (a) Geometric modification of a single microreactor (SMR) maintaining residence time and high mixing efficiency. (b) Scheme for monolithic design of four modified SMR arrays to a 4N-PMR cube. (c) CFD simulation of pressure drop inside a 4N-PMR. (d-1) Captured X-ray scanned 2D image, (d-2) 3D visualization image obtained from X-ray image data, and (d-3) optical image of 4N-PMR, fabricated by a high-resolution 3D selective laser melting printing technique.

To verify the inner distribution performance of the 4N-PMR, the flow rates were simulated at specific locations between the ends of the bifurcation-type distributors and distributed inlets of the modified SMR, at different flow rates of the solvents. All numerically calculated maldistribution factors (MFs), such as the standard deviation of the average mass flow rates, were far less than 1%, which demonstrated the uniform flow distribution behavior of the built-in distributors (see the details in Figure S4). The MF values at the collected outlets were also very low at 0.2%, at a total flow rate of 42 mL min–1, which ensured the equivalent control of flow rates into fluidic channels (Figure 1c).44−46 In addition, the numerical study also verified that the 4N-PMR structure furnished an approximately 3.6 times lower pressure drop inside the channel, compared to the serial channel design of four R1 parts (see the details in Figure S5). In particular, thermal distribution simulation in the compact 4N-PMR demonstrated that the laminated channels rapidly dissipated the exothermic heat generated from the halogen–lithium exchange reaction in the identical manner with the SMR at room temperature (see the details in Figure S6), presumably due to high surface area to volume and good thermal conductivity of metal.

After obtaining the simulation results, a monolithic 4N-PMR incorporating the validated fluidic structure was fabricated using a high-resolution 3D selective laser melting (SLM) method (Figure 1d). The printed fluidic structure was embedded inside a monolithic body of a metal cube (1 cm3). In reality, the internal microchannel structure as a flow path in the opaque metallic 4N-PMR was fully inspected through X-ray computerized tomography (CT) scans (Figure 1d-1) and the 3D visualization image (Figure 1d-2) to ensure that it conformed as designed. These images indicate that the printed channels were fully continuous without significant defects, and their size and geometry were well matched to the initial design. An excellent symmetry of the distributor structures was also observed in the built-in monolithic cube. An aluminum metal frame was used for a tight connection between the three inlets and a single outlet of the 4N-PMR and external tubings (see the details in Figure S7).

The synthetic performance of the fabricated 4N-PMR was comparatively investigated against the capillary SMR by performing a two-step ultrafast subsecond chemistry. Three types of aryllithium intermediates bearing electron-withdrawing groups were generated by halogen–lithium exchange of functionalized aryl halides 1 in R1 over a wide range of temperatures and subsequent reactions with three electrophiles in R2 before decomposition of the intermediates (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ultrafast subsecond flow synthesis using aryllithium intermediates bearing electron-withdrawing groups and various electrophiles at different temperatures in two reactors, the SMR and 4N-PMR.

First, using the capillary SMR, three types of aryllithiums were reacted with methanol to experimentally verify the successful control of short-lived intermediates at different temperatures. The o-lithiophenyl isothiocyanate 1a′ generated from aryl halide 1a and n-BuLi in R1 (4 cm long) produced a high yield of 93% of product 2a at the optimal residence time (∼16 ms) at a flow rate of 7.5 mL min–1 at 25 °C (see the details in Table S2), which is consistent with the reported results.19 Moreover, p-lithiobenzonitrile 1b′ and m-lithionitrobenzene 1c′ obtained from 1b and 1c afforded the protonated products 2e and 2i in identical yields of 87% at optimal temperatures of 024 and −28 °C,23 respectively.

To validate the equivalent performance of the monolithic 4N-PMR, the same chemistries were carried out using the 4N-PMR by feeding the reagents at four times higher flow rates, under the same conditions as applied to the SMR. Both the SMR and 4N-PMR exhibited only a slight difference in yields approximately 2% as shown in Figure 2, proving the same reaction efficiency. Furthermore, aryllithium intermediate 1a′ reacted with phenyl isocyanate to produce a biologically active thioquinazolinone ring compound 2b in yields of 86% for SMR and 85% for 4N-PMR. In the same manner, aryllithiums 1b′ and 1c′ reacted with iodomethane and methyl triflate to give the methylated products 2f with 90% for SMR and 89% for 4N-PMR, and 2j with 86% for SMR and 84% for 4N-PMR, respectively. Three lithiated intermediates were reacted with tributyltin chloride to give the organotin products 2c, 2g, and 2k with similar yields within a 3% difference in both SMR and 4N-PMR. For the synthesis of 2j and 2k, the residence time in R2 was four times longer to reach the best yields, presumably due to the lower reactivity of the reagents at lower temperatures for the control of the nitro-group-bearing aryllithium intermediate. Furthermore, three aryllithium intermediates were reacted with 4-formylbenzonitrile as a pharmacophore with an aromatase inhibitory effect47 to afford the corresponding products 2d, 2h (a letrozole precursor for breast cancer), and 2l in very good to excellent yields. It is worth noting that excellent yields (98%, 86%) of 2h and 2l were achieved at shorter reaction times (0.56 s, 2.24 s) in R2, in contrast to the other reactions mentioned above, where the yields were dramatically reduced to around 50%, at longer reaction times (2.2 s, 9 s), respectively (entries 3 and 6, Table 1). This is presumably ascribed to the decomposition of the lithium methoxide intermediates in R2 without intramolecular cyclization. Eventually, it was found that the yield differences between SMR and 4N-PMR were a range within 3% for all entries, estimated as a result of the uniform distribution of reagent solutions through three inlets. Therefore, these results successfully verified a 4-fold increase in the production of drug scaffolds via two-step ultrafast subsecond chemistry without loss of yield in the 4N-PMR system.

Table 1. Optimization of Residence Time in R2 for the Reaction of Ayllithium Intermediates and 4-Formylbenzonitrile in SMR.

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

The yield was determined by GC.

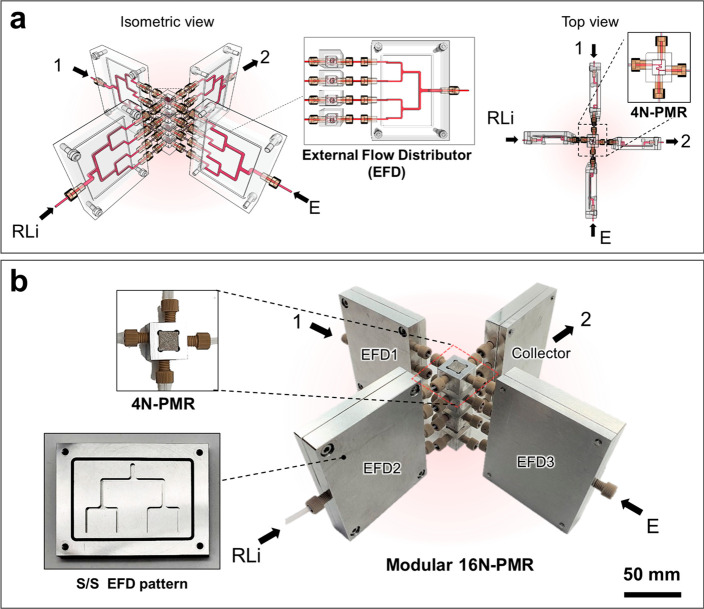

To further scale-up the subsecond synthesis, we devised a 16N-PMR by simply assembling the replicas of highly efficient monolithic 4N-PMR cubes. The 16N-PMR module was constructed by connecting four 4N-PMR cubes and four EFD units with plastic fittings and 1/8 in. tubes (Figure 3). Three stainless steel (S/S) EFDs were configured to uniformly inject the inlet solutions into each 4N-PMR, according to the commonly known geometric ratio of the bifurcation-type distributor.40,45 The other EFD with the same pattern was configured as a collecting outlet for the reaction mixture. The EFDs were also assembled by joining the top and bottom plates patterned by computerized numerical control (CNC) machining (see the details in Figure S8).

Figure 3.

Design concept and fabrication of 16 numbered-up printed microreactor (16N-PMR) assembly. (a) Scheme for four stacked cubes of 4N-PMRs by connecting them with four units of external flow distributors (EFDs). (left) Side view. (right) Top view. (b) Actual 16N-PMR assembly consisting of a 4 × 4N-PMR module, 3 EFD units as inlets, and 1 EFD as a collecting outlet.

Prior to performing ultrafast subsecond synthesis with the 16N-PMR assembly, the inner flow distribution performance of the designed EFD units and the entire system was inspected through CFD simulations and experiments. The fluidic conditions for specific EFD units (96 mL min–1 of THF, 24 mL min–1 of hexane, and 48 mL min–1 of THF) were set to be the same as the actual reaction conditions applied to the 16N-PMR for scale-up production. Initially, the numerical MF values of the three EFD inlet units were individually calculated to be within 2.20% at the outlets (entries 1–3, Table 2; see the details in Figure S9), whereas the experimental MF values in the range of 1.12%–3.45% were obtained by measuring the volumes of collected fluids at four outlets of each EFD unit (entries 1–3, Table 2; see the details in Figure S10).

Table 2. Comparison of Numerical and Experimental Maldistribution Factors (MFs) in the External Flow Distributor (EFD) and 16N-PMR Assembly.

| entry | device | total flow rate [mL/min] | numerical MF [%] | experimental MF [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EFD1 | 96 | 1.73 | 1.12 |

| 2 | EFD2 | 24 | 2.20 | 3.45 |

| 3 | EFD3 | 48 | 1.40 | 2.72 |

| 4 | 16N-PMR | 168 | 1.66 | 1.04 |

Next, a CFD simulation of the modular 16N-PMR assembly was conducted to obtain the numerical MF values from the flow rates at the connection parts from the ends of the built-in EFDs to the inlets of the 4N-PMR. The calculated MF values fell into the range of 1.40–2.20%, when the fluids were individually injected into three EFDs, as assumed (see the details in Figure S11). The MF at the collected outlet also exhibited 1.66% at a total flow rate of 168 mL min–1, which was higher than 0.2% of the built-in 4N-PMR. It is likely that the 3D printed 4N-PMR monolith with a fine inner structure had a more uniform flow distribution function than the 16N-PMR module assembled manually by tubing. In the experiment, the MF value of the entire 16N-PMR was determined to be 1.04%, by measuring the collected volume of liquid at all the four outlets (entry 4, Table 2; see the details in Figure S12). Both the experimental and numerical MF values of 16N-PMR were considerably lower than 5%, which is generally acceptable for chemical synthesis in numbered-up systems.32,39,41,48−50 Note that the modular 16N-PMR assembly of four 4N-PMRs may facilitate the heat dissipation with some interval among the 4N-PMR array. To verify the scalability of this reaction system, the pressure drop as a function of flow rate was numerically simulated for both numbered-up microreactors of 4N-PMR and 16N-PMR (Figure S13) with the pressure gradient throughout the flow path in the 16N-PMR (Figure S14).

Eventually, scalable production in the modular 16N-PMR assembly was carried out under the same conditions as those applied to the SMR and 4N-PMR. The production performance of the 16N-PMR was confirmed by comparing the yields obtained by the SMR and 4N-PMR (Table 3; see the details in Figure S15). Three reagents were individually injected into the 16N-PMR through three EFDs, at flow rates of 96 and 24 mL min–1, for aryl halides and n-BuLi, and 48 mL min–1 for electrophiles, which is 16 times higher than those of the SMR. The scaffolds of S-functionalized thioquinazolinone, letrozole, and torasemide (2b, 2h, and 2j) were obtained with the modular 16N-PMR assembly in yields of 81%, 92%, and 80%, respectively. The results exhibited a slight loss in yields of approximately 5% for all three reactions, which is different from the 2%–3% gain or loss in the performance of 4N-PMR. Presumably, the ultrafast subsecond synthesis is extremely sensitive to the feeding ratio of reagents, whereas both excellent mixing efficiency and accurate residence time control are critical for achieving high yields.19,31 In this study, additional experiments were implemented in the SMR to elucidate the effect of slightly different ratios of reagents in the halogen–lithium exchange reaction in the consideration of numerical MF values. The results revealed that insignificantly different flow rates of the two reagents caused notable yield loss due to insufficient lithiation or side reactions by excessive amounts of organolithium reagents (see the details in Table S2). It must be pointed out that the low MF values of the 16N-PMR assembly within the generally acceptable range in flow chemistry were less tolerable in ultrafast subsecond chemistry.32,39,41,48−50 It is further rationalized that the built-in 4N-PMR monolith with very low MF (0.2%) afforded nearly the same yields as the SMR within the experimental error range, which is much lower than the simulated values (see the details in Figure S10). After all, a 16 times increase in outputs at the optimal condition was successfully achieved by collecting a liter scale of reaction mixture operating for 10 min. The actual isolation of 10–20 g of drug scaffolds provisionally enables production of up to nearly 3 kg day–1 in a compact 16N-PMR system. Furthermore, the larger scalability can be readily established to meet clinical and market needs in the pharmaceutical industry. For that, a conceptual 128N-PMR system as 32 stacks of 4N-PMR modules is designed to operate over the liters per minute scale of flow rate, giving an affordable pressure drop (6.12 × 104 Pa) by numerical analysis as shown in Figures S16 and S17.

Table 3. Scale-up Production of Three Pharmaceutical Scaffolds Including Letrozole Precursor by Using 16N-PMR Assembly and Comparative Synthetic Performance of SMR and 4N-PMR.

| microreactor | yield of 2b [%]a | output of 2b [mg min–1] | yield of 2h [%]b | output of 2h [mg min–1] | yield of 2j [%]c | output of 2j [mg min–1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMR | 86 | 131.2 | 98 | 137.7 | 86 | 70.8 |

| 4N-PMR | 85 | 518.8 | 97 | 545.3 | 84 | 276.5 |

| 16N-PMR | 81 | 1971.0 | 92 | 2068.9 | 80 | 1053.2 |

Yield of isolated product.

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

The yield was determined by GC.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we fabricated a compact cube of 4 numbered-up printed metal microreactors using a high-resolution 3D SLM printing method. The 16N-PMR module was assembled using four 4N-PMRs with external flow distributors so as to scale-up synthesis of ultrafast subsecond chemistry to produce diverse drug scaffolds. Highly reactive aryllithium intermediates were generated in the monolithic 4N-PMR and modular 16N-PMR assembly systems with uniform flow distribution behavior, which were numerically and experimentally demonstrated. The monolithic 4N-PMR embedded with four SMRs and built-in flow distributors furnished four times the productivity with a low pressure drop, giving yields of 84%–99% for 12 products, which is similar to the yields obtained from individual SMRs. Furthermore, the 16N-PMR module exhibited a high production efficiency of 1–2 g min–1 at a slight loss in yields and provisionally produced ∼3 kg of drugs per day. Therefore, this work aims to meet clinical and industrial needs for the efficient production of biologically active compounds via ultrafast subsecond chemistry by using a compact numbering-up system. Moreover, the modular system can be readily reconfigured for a variety of scale-up purposes of on demand synthesis, including the multiplex chemical synthesis of diverse products.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (NRF-2017R1A3B1023598). The fabrication of the 3D-printed microreactor was supported by the General Research Fund (17208218, 17208919, 17204020) of the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong and the Seed Fund for Basic Research (201910159047) of the University Research Committee (URC), the University of Hong Kong.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.1c00972.

(i) Supporting Tables S1–S2, Supporting Figures S1–S17, detailed experimental methods and results, and (ii) spectral data (PDF)

Author Contributions

⊥ J.-H.K. and G.-N.A. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Yoshida J. I.; Kim H.; Nagaki A. Green and Sustainable Chemical Synthesis Using Flow Microreactors. ChemSusChem 2011, 4 (3), 331–340. 10.1002/cssc.201000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvira K. S.; I Solvas X. C.; Wootton R. C. R.; Demello A. J. The Past, Present and Potential for Microfluidic Reactor Technology in Chemical Synthesis. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5 (11), 905–915. 10.1038/nchem.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon C.; Lamanna J.; Wheeler A. R. Printed Microfluidics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27 (11), 1604824. 10.1002/adfm.201604824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli F.; Parisi G.; Degennaro L.; Luisi R. Contribution of Microreactor Technology and Flow Chemistry to the Development of Green and Sustainable Synthesis. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 520–542. 10.3762/bjoc.13.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K. F. Flow Chemistry—Microreaction Technology Comes of Age. AIChE J. 2017, 63 (3), 858–869. 10.1002/aic.15642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akwi F. M.; Watts P. Continuous Flow Chemistry: Where Are We Now? Recent Applications, Challenges and Limitations. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54 (99), 13894–13928. 10.1039/C8CC07427E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda K.; Ichitsuka T.; Koumura N.; Sato K.; Kobayashi S. Flow Fine Synthesis with Heterogeneous Catalysts. Tetrahedron 2018, 74 (15), 1705–1730. 10.1016/j.tet.2018.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pastre J. C.; Browne D. L.; Ley S. V. Flow Chemistry Syntheses of Natural Products. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42 (23), 8849–8869. 10.1039/c3cs60246j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S. G.; Jensen K. F. The Role of Flow in Green Chemistry and Engineering. Green Chem. 2013, 15 (6), 1456–1472. 10.1039/c3gc40374b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ley S. V.; Fitzpatrick D. E.; Myers R. M.; Battilocchio C.; Ingham R. J. Machine-Assisted Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (35), 10122–10136. 10.1002/anie.201501618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta R.; Benaglia M.; Puglisi A. Flow Chemistry: Recent Developments in the Synthesis of Pharmaceutical Products. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016, 20 (1), 2–25. 10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S. Flow “Fine” Synthesis: High Yielding and Selective Organic Synthesis by Flow Methods. Chem. - Asian J. 2016, 11 (4), 425–436. 10.1002/asia.201500916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R.; Lee H. J.; Singh A. K.; Kim D. P. Recent Advances for Serial Processes of Hazardous Chemicals in Fully Integrated Microfluidic Systems. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 33 (8), 2253–2267. 10.1007/s11814-016-0114-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cambié D.; Bottecchia C.; Straathof N. J. W.; Hessel V.; Noël T. Applications of Continuous-Flow Photochemistry in Organic Synthesis, Material Science, and Water Treatment. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116 (17), 10276–10341. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plutschack M. B.; Pieber B.; Gilmore K.; Seeberger P. H. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Flow Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117 (18), 11796–11893. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida J. I.; Nagaki A.; Yamada T. Flash Chemistry: Fast Chemical Synthesis by Using Microreactors. Chem. - Eur. J. 2008, 14 (25), 7450–7459. 10.1002/chem.200800582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida J. I.; Takahashi Y.; Nagaki A. Flash Chemistry: Flow Chemistry That Cannot Be Done in Batch. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49 (85), 9896–9904. 10.1039/C3CC44709J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Nagaki A.; Yoshida J. I. A Flow-Microreactor Approach to Protecting-Group-Free Synthesis Using Organolithium Compounds. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2 (1), 264. 10.1038/ncomms1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Lee H. J.; Kim D. P. Integrated One-Flow Synthesis of Heterocyclic Thioquinazolinones through Serial Microreactions with Two Organolithium Intermediates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (6), 1877–1880. 10.1002/anie.201410062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Lee H. J.; Kim D. P. Flow-Assisted Synthesis of [10]Cycloparaphenylene through Serial Microreactions under Mild Conditions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (4), 1422–1426. 10.1002/anie.201509748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Yonekura Y.; Yoshida J. I. A Catalyst-Free Amination of Functional Organolithium Reagents by Flow Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (15), 4063–4066. 10.1002/anie.201713031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanjaneyulu B. T.; Vidyacharan S.; Ahn G. N.; Kim D. P. Ultrafast Synthesis of 2-(Benzhydrylthio)Benzo[: D] Oxazole, an Antimalarial Drug, via an Unstable Lithium Thiolate Intermediate in a Capillary Microreactor. React. Chem. Eng. 2020, 5 (5), 849–852. 10.1039/D0RE00038H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaki A.; Kim H.; Yoshida J.-i. Nitro-Substituted Aryl Lithium Compounds in Microreactor Synthesis: Switch between Kinetic and Thermodynamic Control. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48 (43), 8063–8065. 10.1002/anie.200904316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaki A.; Kim H.; Usutani H.; Matsuo C.; Yoshida J. I. Generation and Reaction of Cyano-Substituted Aryllithium Compounds Using Microreactors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8 (5), 1212–1217. 10.1039/b919325c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomida Y.; Nagaki A.; Yoshida J. I. Asymmetric Carbolithiation of Conjugated Enynes: A Flow Microreactor Enables the Use of Configurationally Unstable Intermediates before They Epimerize. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (11), 3744–3747. 10.1021/ja110898s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren W.; Kim H.; Lee H. J.; Wang J.; Wang H.; Kim D. P. A Pressure-Tolerant Polymer Microfluidic Device Fabricated by the Simultaneous Solidification-Bonding Method and Flash Chemistry Application. Lab Chip 2014, 14 (21), 4263–4269. 10.1039/C4LC00560K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller S. T. R.; Hokamp T.; Ehrmann S.; Hellier P.; Wirth T. Ethyl Lithiodiazoacetate: Extremely Unstable Intermediate Handled Efficiently in Flow. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22 (34), 11940–11942. 10.1002/chem.201602133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. J.; Kwak C.; Kim D. P.; Kim H. Continuous-Flow Si-H Functionalizations of Hydrosilanesviasequential Organolithium Reactions Catalyzed by Potassiumtert-Butoxide. Green Chem. 2021, 23 (3), 1193–1199. 10.1039/D0GC03213A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. N.; Park C.; Whitesides G. M. Solvent Compatibility of Poly(Dimethylsiloxane)-Based Microfluidic Devices. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75 (23), 6544–6554. 10.1021/ac0346712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Min K. I.; Inoue K.; Im D. J.; Kim D. P.; Yoshida J. I. Submillisecond Organic Synthesis: Outpacing Fries Rearrangement through Microfluidic Rapid Mixing. Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 2016, 352 (6286), 691–694. 10.1126/science.aaf1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. J.; Roberts R. C.; Im D. J.; Yim S. J.; Kim H.; Kim J. T.; Kim D. P. Enhanced Controllability of Fries Rearrangements Using High-Resolution 3D-Printed Metal Microreactor with Circular Channel. Small 2019, 15 (50), 1905005. 10.1002/smll.201905005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y.; Kuijpers K.; Hessel V.; Noël T. A Convenient Numbering-up Strategy for the Scale-up of Gas-Liquid Photoredox Catalysis in Flow. React. Chem. Eng. 2016, 1 (1), 73–81. 10.1039/C5RE00021A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thaisrivongs D. A.; Naber J. R.; McMullen J. P. Using Flow to Outpace Fast Proton Transfer in an Organometallic Reaction for the Manufacture of Verubecestat (MK-8931). Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016, 20 (11), 1997–2004. 10.1021/acs.oprd.6b00247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thaisrivongs D. A.; Naber J. R.; Rogus N. J.; Spencer G. Development of an Organometallic Flow Chemistry Reaction at Pilot-Plant Scale for the Manufacture of Verubecestat. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2018, 22 (3), 403–408. 10.1021/acs.oprd.7b00385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berton M.; de Souza J. M.; Abdiaj I.; McQuade D. T.; Snead D. R. Scaling Continuous API Synthesis from Milligram to Kilogram: Extending the Enabling Benefits of Micro to the Plant. J. Flow Chem. 2020, 10 (1), 73–92. 10.1007/s41981-019-00060-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque F.; Rogus N. J.; Spencer G.; Grigorov P.; McMullen J. P.; Thaisrivongs D. A.; Davies I. W.; Naber J. R. Advancing Flow Chemistry Portability: A Simplified Approach to Scaling Up Flow Chemistry. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2018, 22 (8), 1015–1021. 10.1021/acs.oprd.8b00063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ufer A.; Mendorf M.; Ghaini A.; Agar D. W. Liquid/Liquid Slug Flow Capillary Microreactor. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2011, 34 (3), 353–360. 10.1002/ceat.201000334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni A. A.; Nivangune N. T.; Joshi R. R.; Joshi R. A. Continuous Flow Multipoint Dosing Approach for Selectivity Engineering in Sulfoxidation. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013, 17 (10), 1293–1299. 10.1021/op400138v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaki A.; Hirose K.; Tonomura O.; Taniguchi S.; Taga T.; Hasebe S.; Ishizuka N.; Yoshida J. I. Design of a Numbering-up System of Monolithic Microreactors and Its Application to Synthesis of a Key Intermediate of Valsartan. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016, 20 (3), 687–691. 10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F.; Cambié D.; Janse J.; Wieland E. W.; Kuijpers K. P. L.; Hessel V.; Debije M. G.; Noël T. Scale-up of a Luminescent Solar Concentrator-Based Photomicroreactor via Numbering-Up. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6 (1), 422–429. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b02687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu M.; Zha L.; Song Y.; Xiang L.; Su Y. Numbering-up of Capillary Microreactors for Homogeneous Processes and Its Application in Free Radical Polymerization. React. Chem. Eng. 2019, 4 (2), 351–361. 10.1039/C8RE00224J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawagoe Y.; Moriyama K.; Togo H. One-Pot Transformation of Methylarenes into Aromatic Nitriles with Inorganic Metal-Free Reagents. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 2014 (19), 4115–4122. 10.1002/ejoc.201402270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn G. N.; Yu T.; Lee H. J.; Gyak K. W.; Kang J. H.; You D.; Kim D. P. A Numbering-up Metal Microreactor for the High-Throughput Production of a Commercial Drug by Copper Catalysis. Lab Chip 2019, 19 (20), 3535–3542. 10.1039/C9LC00764D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim S. J.; Ramanjaneyulu B. T.; Vidyacharan S.; Yang Y. D.; Kang I. S.; Kim D. P. Compact Reaction-Module on a Pad for Scalable Flow-Production of Organophosphates as Drug Scaffolds. Lab Chip 2020, 20 (5), 973–978. 10.1039/C9LC01099H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn G. N.; Sharma B. M.; Lahore S.; Yim S. J.; Vidyacharan S.; Kim D. P. Flow Parallel Synthesizer for Multiplex Synthesis of Aryl Diazonium Libraries via Efficient Parameter Screening. Commun. Chem. 2021, 4 (1), 1–8. 10.1038/s42004-021-00490-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming F. F.; Yao L.; Ravikumar P. C.; Funk L.; Shook B. C. Nitrile-Containing Pharmaceuticals: Efficacious Roles of the Nitrile Pharmacophore. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53 (22), 7902–7917. 10.1021/jm100762r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saber M.; Commenge J. M.; Falk L. Microreactor Numbering-up in Multi-Scale Networks for Industrial-Scale Applications: Impact of Flow Maldistribution on the Reactor Performances. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65 (1), 372–379. 10.1016/j.ces.2009.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers K. P. L.; Van Dijk M. A. H.; Rumeur Q. G.; Hessel V.; Su Y.; Noël T. A Sensitivity Analysis of a Numbered-up Photomicroreactor System. React. Chem. Eng. 2017, 2 (2), 109–115. 10.1039/C7RE00024C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Mas N.; Günther A.; Kraus T.; Schmidt M. A.; Jensen K. F. Scaled-out Multilayer Gas-Liquid Microreactor with Integrated Velocimetry Sensors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2005, 44 (24), 8997–9013. 10.1021/ie050472s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.