Introduction

Prostate cancer remains the first solid tumor to demonstrate the overall survival (OS) of an autologous cellular therapy, Sipuleucel-T (1), but despite its success, understanding why prostate cancer has been refractory to a wide range of subsequent immune platforms remains unclear. Modulations in PSA have been demonstrated in several approaches (2), but despite the success demonstrating survival benefit in a phase II trial of PROSTVAC (rilimogene galvacirepvec/rilimogene glafolivec or F-PSA-TRICOM; PROSTVAC-V (3), a viral-based immunotherapy consisting of a vaccinia virus and recombinant fowlpox virus given as a prime boost. Both viruses encode modified forms of Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) along with three co-stimulatory molecules, B7.1 (CD80), with intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-3 (LFA-3). The phase II study cited a prolonged median OS of 8.5 months versus placebo in men with castration resistant prostate cancer (3); the randomized phase III (4) trial did need not meet its primary endpoint of OS in men with castrated metastatic prostate cancer. In fact, at the third interim analysis, criteria for futility were made and the trial was stopped early. The study was designed to compare the superiority of PROSTVAC or PROSTVAC plus Granulocyte/Macrophage Stimulating Factor (GMCSF), versus placebo. Although PROSTVAC induced T cell-specific responses against PSA as well as “cascade” antigens (4,5) the immune response did not translate into clinical benefit.

Targeting the tumor microenvironment – a challenge?

However, it remains unclear whether the lack of response to multiple immunologic approaches is due to one cellular population or a combination of cytokines, cells and inhibitory factors within this setting. Failures of immune-based therapies have been attributed to the “bland” or “cold” tumor microenvironment of prostate cancer due to lack of CD8 infiltration; inhibitory pathways such as adenosine (6,7), or cellular populations such as Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs), Colony Stromal Factor-1 (CSF-1) or inhibitory macrophages have been closely studied. Multiple agents are currently in clinical trials targeting each of these pathways and cellular populations but to date, no agent alone has met with success. More recently (8), the inhibition of BRD4, member of the Bromodomain and ExtraTerminal (BET) family of bromodomain-containing proteins has been shown to reduce levels of several target genes under Androgen Receptor (AR) control and can reduce tumor size in preclinical models. It has been postulated that in its role as a transcriptional regulator, BRD4 recruitment may participate in mediating AR and other oncogenic drivers such as MYC but may have a potential role in immune regulations. As such, targeting BET bromodomains using a small molecule inhibitor has been shown to decrease PD-L1 expression and reduce tumor progression in prostate cancer models. It is likely that BET bromodomain inhibition works via increasing MHC class I expression thereby increasing the immunogenicity of tumor cells. Furthermore, transcriptional profiling showed that BET bromodomain inhibition can modulate several networks that are involve in antigen processing and immune checkpoint molecules. Murine models treated with an inhibitor have demonstrated increased CD8/Treg populations suggesting that there may be a role for using a bromodomain inhibitor along with a checkpoint inhibitor (8) in patients.

The greatest conundrum is why prostate cancers have been relatively resistant to checkpoint inhibitors. While a phase I/II trial (9) using different doses of ipilimumab given alone or following radiation showed long-term benefit and even remission in a minority of patients, nevertheless two phase III trials (10,11) both in early and late disease, respectively, did not meet their endpoints of survival, albeit, the “tail end” of the survival curve had patients with durable responses. Efforts to explain the lack of responsiveness of prostate cancer to this family of immune therapies remains an active area of study. Anecdotal case reports have suggested that some form of “immune modulation” can be seen if patients received enzalutamide first prior to receiving Sipuleucel-T leading to a dramatic decline in PSA. In one case report (12), a patient who had been in a clinical atrial and had received GM-CSF therapy resulting in “a saw tooth like pattern of PSA declines during treatment, developed continued rises in PSA with development of castration resistant disease to bone. He went on to treatment with enzalutamide with improvement in disease with declines in PSA but then developed rising PSAs. He then received Sipuleucel-T while continuing the enzalutamide and androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) and after six months developed a marked decline in PSA to <0.05 that lasted for over one year with regression of metastatic disease. This is clearly an unusual scenario but raises the question of whether or not enzalutamide can enhance the effects not only of Sipuleucel-T but other immune-based therapies as well. The fact that there was a delay in response may be attributed to an “immune based mechanism” given prior results from Sipuleucel-T trials that suggested a robust increase in antigen presenting cell (APC) upregulation. This patient had similar findings. Others (13,14) have demonstrated in small studies that patients with visceral metastases in the presence of genomic alterations such as BRCA 1,2 or MSIhi can respond robustly to pembrolizumab with long-term responses. This has led to a further inquiry as to how these agents may be used in patients with these genomic alterations and whether or not combinations with these agents may provide significant long-term benefits to patients who are otherwise refractory to standard androgen signaling inhibitors or chemotherapies. Antonarakis, et al (15) in a multicohort Keynote 199 study, demonstrated that there may be benefit in a small but unique cohort of patients who received single agent pembrolizumab, reinforcing our continued efforts to further define patients who may derive benefits from this therapeutic class of drugs (16).

Lethal prostate cancer - does it exist and can we treat it?

The term “lethal” has taken on many connotations from a type of tumor that is aggressive at the time of diagnosis with rapid progression to terminal disease. More recently, it has come to be understood as a unique phenotype that has evolved following treatment with androgen-receptor signaling inhibitors such as enzalutamide and abiraterone, to unusual histologic subtypes as neuroendocrine prostate cancer (17). While adenocarcinoma remains the predominant histologic phenotype of prostate cancer and displays features suggestive of luminal prostate cells that are under androgen regulation, de novo small cell carcinoma of the prostate can appear that often bears similar histology to small cell carcinoma of the lung. This prostate variant can also appear later in the disease in the more treatment refractory setting, often posing a challenge for the treating physician as standard small cell chemotherapies do not provide durable responses. There has been a clinical lack of clarity with response to terminology as small cell does not always mean neuroendocrine cancer given that there are features that are either mixed to suggest that small cell and neuroendocrine or poorly differentiated prostate cancer can all align together. As such, the mixed histologic features within a continuum of histologic and behavioral evolution are encompassed under the umbrella of “neuroendocrine prostate cancer” with clear delineations regarding survival (17), Figure 1.

Figure 1 –

Overall survival (OS) in a cohort of patients with neuroendocrine prostate cancer showing multiple histologic patterns with neuroendocrine disease. Panel (A) represents OS from diagnoses of adenocarcinoma versus (B), diagnosis of NEPC. OS of mixed histology is in panel (C) with neuroendocrine histology in panel (D). OS in de novo versus therapy-related NEPC from diagnosis of prostate cancer € and from diagnosis of NEPC (F). Different axes represent different time scales used for A, C and E compared with B, D, F due to different time intervals between OS from prostate cancer diagnosis and OS from NEPC diagnosis.

From Graff JN, Alumkal JJ, Thompson RF, et al. Pembrolizumab (Pembro) plus enzalutamide (Enz) in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): Extended followup. J Clin Onc 20198; Abstr #5047, GU ASCO; with permission.

Treating the “lethal’ phenotype based on genomics

Carreira, et al (18) suggest that there are unique tumor adaptations that may underlie resistance to repeated AR targeting in CRPC. As such, using targeted sequencing and computational approaches, they have systematically profiled genomic changes in a patient’s tumor to demonstrate unique mutations in sites of metastatic disease that correspond to behavioral changes within the tumor and demonstrate clonal architectural heterogeneity at different stages of disease progression. This management paradigm may offer a means by which early identification of “lethality” can be identified and treatments can be re-directed to the more aggressive clones. Aggarwal, et al (19), systematically analyzed 202 patients of whom 148 had prior disease progression on abiraterone and/or enzalutamide and who underwent routine biopsies. The overall incidence of small cell neuroendocrine prostate cancer was 17% with AR amplification and protein expression noted in 67 and 75% respectively. Detection of neuroendocrine cancer was associated with shortened overall survival among patients with prior AR-targeting therapy [hazard ratio, 2.02, 95% CI, 1.07 to 3.82]. A “transcriptional signature” was also developed and validated with >90% accuracy and seems to indicate that this phenotype arises in the context of TP53 and RB1 aberration from adenocarcinoma under a selective process if not pressure of inhibition of the AR pathway (20). They reported frequent loss of TP53 and/or RB1 at the genome level along with upregulation of E2F. Interestingly, DEK (21) was the highest overexpressed E2F1 target gene in the small cell/neuroendocrine cluster with prior implication into the progression to this phenotype. Other transcriptional factors that have been documented into the progression into small cell/neuroendocrine prostate cancer include POU class 3 homeobox, FOX A2, ASCL1, and 2 (BRN2).

It is clear that from a behavioral and histologic standpoint, these “lethal” cancers may also have a unique response to immune agents. Wu, et al (22) have subsequently identified a unique subtype of prostate cancer that is associated with bi-allelic loss of CDK12 and is mutually exclusive with tumors driven by DNA repair deficiency in addition to ETS fusions and a variety of mutations in SPOP. CDK12 is a cyclin-dependent kinase that forms a heterodime5ric complex with cyclin K, its activating partner. Together, they regulate a variety of processes that regulate gene expression (20). Using an integrative genomic analysis of 360 samples from patients with mCRPC, samples that had CDK12 mutants were associated with increasing burden of neoantigens and increased infiltration and/or clonal expansion of tumor T cells. Interestingly, while most CDK12 mutants retained active androgen receptor (AR) suggesting sensitivity to AR blocking or signaling inhibitors, they had a distinct expression signature that was characterized by increased gene fusions as well as increased gene fusion-induced neoantigen open reading frames. The latter served as rationale for exploring the susceptibility of those tumors with higher neoantigen burden could respond to alternative lines of therapy. Also in keeping with known susceptibility to checkpoint inhibitors, is an inflammatory milieu suggesting a “hot” tumor microenvironment which is known to be more amenable to immune-based therapies, in particular checkpoint inhibitors. As such, the authors found activation of cancer inflammatory gene sets in CDK12 mutant tumors (Figure 2). More importantly, one patient who was treated with anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor and had a PSA response following four cycles of drug also had membranous and cytoplasmic staining of CD3 in addition to a radiographic response. As such, these results suggest that CDK12 may represent a potential biomarker in tumors with elevated neoantigen burden and which may benefit from checkpoint blockade. There are ongoing clinical trials in different clinical states: NCT04104893, a phase II study exploring activity and efficacy of pembrolizumab I Veterans with mCRPC with either mismatch repair deficiency or CDK12 inactivation, and NCT03570619, a phase II trial using ipilimumab and nivolumab combination therapy followed by nivolumab monotherapy in patients with mCRPC harboring loss of CDK12 function, respectively among others in order to further explore this hypothesis.

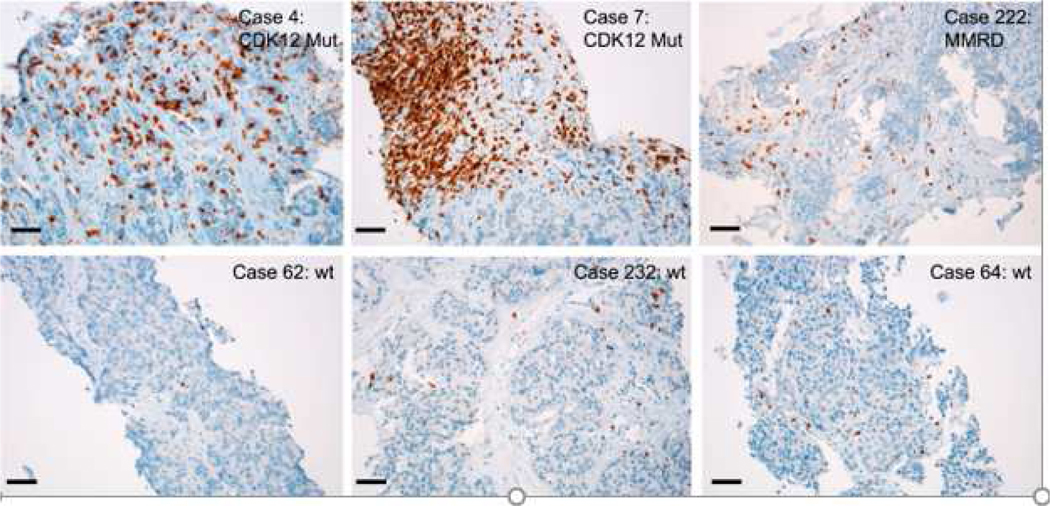

Figure 2 –

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor sections showing T cell infiltration by CD3+ cells. Six cases are shown with two showcasing CDK12 mutant tumors, one MMRD tumor and three that are wild type for CDK12, mismatch repair (MMR) genes and homologous repair (HR) genes.

From Aggarwal R, Huang J, Alumkal JI, et al. Clinical and genomic characterization of treatment-emergent small cell-neuroendocrine prostate cancer: A multi-institutional prospective study. J Clin Onc 2018; 36:2492–2503; with permission.

Immunotherapy in prime time – the role of biomarkers.

A number of technology platforms are being implemented to assess peripheral blood and tissue based biomarkers; of these RNA-seq, flow and mass cytometry and enzyme-linked immuosorbent assay(ELISA)-based assays have been in widespread use (24). There are still multiple challenges in using immune approaches in patients with mCRPC. It is clear that understanding the genetic backgound of the tumor and its host is highly relevant in certain cases but at this time, one treatment does not fit all patients. Biomarkers may be in the form of changes in imaging using unique tracers, tumor mutational changes, mutational burden, presence or absence of PD-1 or PD-L1 on tumor or immune cells, circulating tumor cells (CTCs) or tumor or cell free DNA, however, biomarkers that are unique to assess changes within the tumor microenvironment or in the peripheral blood have not as yet been well-defined despite multiple efforts. Several solid tumors have relied upon the presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) to develop and “immunoscore” to determine the amount of immunologic activity that is in situ within the tumor, however, prostate is unique in that it is rare to see TILs either at diagnosis or in the setting of progressive disease. The ratio of Tregs/MDSCs has been explored; CD4+FOXP+CD24hi Tregs have been associated with poor prognosis. In addition, Treg frequency among TILs has been shown to correlate with tumor grade and reduced patient survival in several solid tumors including breast, melanoma, glioblastoma and ovarian cancers.

What is now observed in multiple clinical trials with checkpoint inhibitors for several solid tumors such as renal or urothelial cancers, is that the presence or absence of PD-L1 does not seem to impact treatment response. Gnjatic, et al (25) have provided guidance from Working Group 4 from the Society of Immunotherapy’s (SITC) Immune Biomarkers Task Force in an attempt to discover host genetic factors, tumor alterations in genes that affect APC function or affect local recruitment of inflammatory cells into the tumor microenvironment. Their work is one of many groups who continue to provide immune monitoring throughout the disease continuum in an effort to determine how to best characterize the immune system’s role in disease response. These efforts are to be lauded as they provide multidisciplinary, multi-institutional viewpoints that allow for greater insight into understanding the layers that govern the immune system’s control of disease response.

Discussion

There is a significant thrust toward the further genomic profiling of prostate tumors along the disease continuum with each new clone likely harboring unique mutations to which novel drugs can be targeted. This does not however, address the issue as to how to best target the disease in toto as not all drugs target all sites of disease equally and sometimes not at all. We have come a very long way and are beginning to understand the conditions whereby the immune system can be better engaged with novel therapies. It is clear that no one drug is able to provide complete therapeutic response alone; therefore continued efforts to combine different classes of agents along with immunologic therapies remain a viable long-term goal for researchers and practitioners alike.

Key points:

Immunotherapy for prostate cancer has been limited by a “bland” or “cold” tumor microenvironment

Multiple mechanisms exist within the tumor microenvironment that inhibit infiltration of immune cells

Small cell/neuroendocrine prostate cancer represents a unique histologic phenotype that may occur de novo or may emerge following failure of androgen receptor signaling inhibitors

CDK12 mutated prostate cancer represent a unique group of tumors with limited sensitivity to checkpoint inhibitors

Synopsis.

Multiple immunologic platforms have provided minimal impact in patients with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) necessitating that novel approaches continue to be developed. While prostate cancer is the first solid tumor with an autologous cellular therapy that provides an overall survival benefit, nevertheless, robust antitumor responses have been limited in this patient population with this therapy alone albeit in combination with other agents has shown recruitment of T cells within the peripheral blood along with dendritic cells suggesting immune activation. Although checkpoint inhibitors have been largely ineffective in these patients, there remain small cohorts of patients who have durable responses but lack the conventional indicators for response to this class of drugs, ie, high mutational burden or significant genomic alterations, as seen in other solid tumors. This article presents an update on the evolution of immunotherapeutics that target a more lethal form of prostate cancer and provides the groundwork for future considerations as to how this field should proceed.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The author has nothing to disclose

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Eng J Med 2010; 363:411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNeel DG, Eickhoff JC, Johnson LE, et al. Phase II trial of a DNA vaccine encoding Prostatic Acid Phosphatase (pTVG-HP [MVI-816] in patients with progressive, nonmetastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Onc 2019; 37: 3507–3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantoff PW, Schuetz TJ, Blumentstein BA, et al. Overall survival analysis of a phase II randomized controlled trial of a poxviral-base PSA-targeted immunotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Onc 2010: 28:1099–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulley JL, Borre M, Vogelzang NJ, et al. Phase III trial of PROSTVAC in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Onc 2019; 37: 1051–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gulley JL, Madan RA, Tsang Ky, et al. Immune impacted induced by PROSTVAC (PSA-TRICOM), a therapeutic vaccine for prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2014; 2:133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sek K, Molck C, Stewart GD, Kats L, Darcy PK, Beavis PA. Targeting adenosine receptor signaling in cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19:3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vigano S, Alatzoglou D, Irving M, Menetrier-Caux C, Caux C, Romero P, Coukos G. Targeting adenosine in cancer immunotherapy to enhance T-cell function. Front Immunol 2019; epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao W, Ghasemzadeh A, Freeman ZT, et al. Immunogenicity of prostate cancer is augmented by BET bromodomain inhibition. J Immunother Cancer 2019; 7:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slovin SF, Higano CS, Hamid O, et al. Ipilimumab alone or in combination with radiotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from an open-label, multicenter phase I/II study. Ann Oncol 2013; 24:1813–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beer TM, Kwon ED, Drake CG, et al. Randomized, double-blind, phase III trial of Ipilimumab versus placebo in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients with metastatic chemotherapy-naïve castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Onc 2017; 35:40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon ED, Drake CG, Scher HI, et al. Ipilimumab versus placebo after radiotherapy in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that had progressed after docetaxel chemotherapy CA184–043): a multicenter, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15:700–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graff JN, Drake CG, Beer TM. Complete biochemical (Prostate-Specific Antigen) response to sipuleucel-T with enzalutamide in castration-resistant prostate cancer: A case report with implications for future research. Urology 2013; 81:381–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graff JN, Alumbal JJ, Drake CG, et al. Early evidence of anti-PD-1 activity in enzalutamide-resistant prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2016; 7:52810–52817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graff JN, Alumkal JJ, Thompson RF, et al. Pembrolizumab (Pembro) plus enzalutamide (Enz) in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): Extended followup. J Clin Onc 20198; Abstr #5047, GU ASCO. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antonarakis ES, Piulats JM, Gross-Goupil M, et al. Pembrolizumab for treatmentrefractory castration-resistant prostate cancer: multicohort, open-label phase II KEYNOTE-199 study. J Clin Onc 202; 38:395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slovin SF. Pembrolizumab in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Can an agnostic become a believer. J Clin Onc 2019; 38: 381–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conteduca V, Oromendia C, Eng KW, et al. Clinical features of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carreira S, Romanel A, Goodall J, et al. Tumor clone dynamics in lethal prostate cancer. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aggarwal R, Huang J, Alumkal JI, et al. Clinical and genomic characterization of treatment-emergent small cell-neuroendocrine prostate cancer: A multi-institutional prospective study. J Clin Onc 2018; 36:2492–2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akamatsu S, Wyatt AW, Lin D, et al. The placental gene PEG10 promotes progression of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Cell Reports 2015; 12:922–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin D, Dong X, Wang K, et al. Identification of DEK as a potential therapeutic target for neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2015; 6:1806–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Y-M, Cieslik M, Lonigro RJ, et al. Inactivation of CDK12 delineates a distinct immunogenic class of advanced prostate cancer. Cell 2018; 173:1770–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng S-W, Kuzyk MA, Moradian A, et al. Interaction of cyclin-dependent kinase 12/CrkRS with cyclin K1 is required for the phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Bio 2012; 32:4691–4704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nixon AB, Schalper KA, Jacobs I, et al. Peripheral immune-based biomarkers in cancer immunotherapy: can realize their predictive potential. J Immunother Cancer 2019; 7:325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gnjatic S, Bronte V, Brunet LR, et al. Identifying baseline immune-related biomarkers to predict clinical outcome of immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2017; 5:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]