Abstract

Orexins/hypocretins are synthesized in neurons of the perifornical, dorsomedial, lateral, and posterior hypothalamus. A loss of hypocretin neurons has been found in human narcolepsy, which is characterized by sudden loss of muscle tone, called cataplexy, and sleepiness. The normal functional role of these neurons, however, is unclear. The medioventral medullary region, including gigantocellular reticular nucleus, alpha (GiA) and ventral (GiV) parts, participates in the induction of locomotion and muscle tone facilitation in decerebrate animals and receives moderate orexinergic innervation. In the present study, we have examined the role of orexin-A (OX-A) in muscle tone control using microinjections (50 μM, 0.3 μl) into the GiA and GiV sites in decerebrate rats. OX-A microinjections into GiA sites, previously identified by electrical stimulation as facilitating hindlimb muscle tone bilaterally, produced a bilateral increase of muscle tone in the same muscles. Bilateral lidocaine microinjections (4%, 0.3 μl) into the dorsolateral mesopontine reticular formation decreased muscle rigidity and blocked muscle tone facilitation produced by OX-A microinjections into the GiA sites. The activity of cells related to muscle rigidity, located in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus and adjacent reticular formation, was correlated positively with the extent of hindlimb muscle tone facilitation after medullary OX-A microinjections. OX-A microinjections into GiV sites were less effective in muscle tone facilitation, although these sites produced a muscle tone increase during electrical stimulation. In contrast, OX-A microinjections into the gigantocellular nucleus (Gi) sites and dorsal paragigantocellular nucleus (DPGi) sites, previously identified by electrical stimulation as inhibitory points, produced bilateral hindlimb muscle atonia. We propose that the medioventral medullary region is one of the brain stem target for OX-A modulation of muscle tone. Facilitation of muscle tone after OX-A microinjections into this region is linked to activation of intrinsic reticular cells, causing excitation of midbrain and pontine neurons participating in muscle tone facilitation through an ascending pathway. Moreover, our results suggest that OX-A may also regulate the activity of medullary neurons participating in muscle tone suppression. Loss of OX function may, therefore, disturb both muscle tone facilitatory and inhibitory processes at the medullary level.

INTRODUCTION

The orexins (OXs) or hypocretins are synthesized in neurons of the perifornical, dorsomedial, lateral, and posterior hypothalamus (de Lecea et al. 1998; Sakurai et al. 1998). OXs have been implicated in the regulation of various brain and body functions, such as feeding (Lubkin and Stricker-Krongrad 1998; Sakurai et al. 1998; Sweet et al. 1999; Takahashi et al. 1999), energy homeostasis (Moriguchi et al. 1999; Williams et al. 2000), neuroendocrine (Nowak et al. 2000; Pu et al. 1998) and cardiovascular processes (Samson et al. 1999), sleep (Bourgin et al. 2000; John et al. 2000; Xi et al. 2001), locomotion (Hagan et al. 1999; Nakamura et al. 2000), and muscle tone control (Kiyashchenko et al. 2001; Siegel 1999). It has been shown that most human narcoleptics have reduced levels of hypocretin-1 (OX-A) in their cerebrospinal fluid and brain (Nishino et al. 2000; Peyron et al. 2000). In addition, a massive loss of OX-synthesizing hypothalamic cells is linked to human narcolepsy (Thannical et al. 2000). It has been reported that mutation of the hypocretin receptor-2 gene is the genetic cause of canine narcolepsy (Lin et al. 1999). Mice with a null mutation of the prepro-orexin gene show symptoms of narcolepsy (Chemelli et al. 1999), including sudden loss of muscle tone.

We have recently examined the role of orexin-A (OX-A) and orexin-B (OX-B) in muscle tone control using microinjections into the locus coeruleus (LC) and pontine inhibitory area (PIA), including middle portions of the oral and caudal pontine reticular nuclei and subcoeruleus region in decerebrate rats. OX-A and OX-B microinjections into the LC produced ipsilateral or bilateral hindlimb muscle tone facilitation, and microinjections into the PIA evoked bilateral muscle atonia (Kiyashchenko et al. 2001). LC neurons receive the densest extrahypothalamic OX projections (Hagan et al. 1999; Horvath et al. 1999; Nambu et al. 1999; Peyron et al. 1998), facilitate spinal motoneurons (Holstege and Kuypers 1987; White and Neuman 1980, 1983), and abruptly cease discharge at cataplexy onset (Wu et al. 1999). Peyron et al. (1998) reported that medioventral medullary region, including the alpha (GiA) and ventral (GiV) parts of the gigantocellular nucleus (Gi), receives moderate OX innervation. Electrical and chemical stimulation of this region produces controlled locomotion and muscle tone facilitation in decerebrate cats and rats (Garcia-Rill and Skinner 1987a; Kinjo et al. 1990). Garcia-Rill et al. (1983, 1986) reported that the medioventral medullary region inducing locomotion receives the majority of descending projections from the midbrain locomotor region (MLR), including the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPTg) and caudal half of the cuneiform nucleus (CnF). Electrical and chemical stimulation of this midbrain region also induces locomotion on a treadmill (Garcia-Rill et al. 1983; Skinner and Garcia-Rill 1984) and facilitates muscle tone (Juch et al. 1992; Lai and Siegel 1990a) in decerebrate cats and rats.

The present study was undertaken to determine whether muscle tone changes could be produced by OX-A microinjections into the medioventral medullary region and which neuronal mechanisms may be involved.

METHODS

All procedures were approved by the Animal Studies Committee of the Sepulveda V.A. Medical Center/UCLA in accordance with U.S. Public Health Service guidelines. Forty-two Wistar rats (250–300 g) were operated on, and 33 of them showed muscle rigidity within 0.5–3 h after decerebration with hindlimb electromyogram (EMG) amplitudes ranging from 30 to 400 μV. Nine animals, with EMG level less than 30 μV, were used to investigate the role of rigidity in OX-A and lidocaine effects on muscle tone.

Surgery

Animals were anesthetized with halothane, followed by ketamine HCL (Ketalar; 70 mg/kg ip) for cannulation of the trachea and decerebration. Two holes (2 mm diam) were drilled over the skull above the MLR and PIA, 8.5 mm posterior to bregma and 1.6 mm lateral to the midline, for the insertion of cannulae, stimulating and unit recording electrodes (Hajnik et al. 2000; Milner and Mogenson 1988). One hole (2.0 mm diam) was drilled above the GiA, GiV, Gi, and dorsal paragigantocellular nucleus (DPGi), 11.0 mm posterior to bregma, for the insertion of stimulating electrodes and cannulae. Coordinates of all structures were based on the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1997).

Two rectangular holes were cut in each parietal bone in preparation for decerebration. The transverse anterior and posterior borders of these holes were located 1 and 5 mm posterior to bregma, with the longitudinal sagittal border 0.5 mm from the midline. Precollicular-postmammillary decerebration was performed 4.0–5.0 mm posterior to bregma with a stainless steel spatula, taking care not to injure the sagittal vein. Excess fluid was aspirated by syringe and absorbed with Gelfoam (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ/Upjohn, Kalamazo, MI). Then anesthesia was discontinued. Rectal temperature was continuously monitored with an electrical thermometer (model BAT-12; Physitemp Instruments, Clifton, NJ) and maintained between 37 and 38°C with a Heat Therapy Pump (model TP-500; Gaymar Industries, Orchard Park, NY). Experiments were begun when postdecerebrate muscle rigidity appeared (0.5–3 h after decerebration).

Stimulation and recording

Electrical stimulation (0.2 ms; 50 Hz; 30–200 μA, continuous stimulation 10–15 s) via tungsten monopolar microelectrodes (A-M Systems, Carlborg, WA) was used to identify the midbrain, pontine, and medullary sites producing muscle tone facilitation and muscle tone inhibition. Stimulation was performed using electrode insertion in increments of 0.3 mm. Cathodal stimuli were delivered using a S88 stimulator (Grass Instrument) and Grass SIU5 stimulus isolation unit. The anode, a screw electrode, was placed in the frontal cranial bone. Bipolar stimulating electrodes (stainless steel, 100 μm, tip separation 80–100 μm) were used for reduction of electrical artifact during unit recording. Stimulation artifact was determined to have a duration of less than 1.3 ms. Bipolar stimulating electrodes were inserted in the pontine reticular nucleus, oral part (PnO), 8.3–8.8 mm posterior to bregma, 0.6–1.6 mm lateral to the midline, and 8.5–9.5 mm below the skull. This region was identified previously as rostral part of the PIA, producing bilateral muscle tone suppression in decerebrate rats (Hajnik et al. 2000).

Extracellular unit recordings were performed using monopolar tungsten microelectrodes (A-M Systems, Carlborg, WA). Spikes were amplified with a model 1700 A-M Systems amplifier. EMG was recorded from the gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior muscles bilaterally with stainless steel wires (100 μm) and amplified using a Grass polygraph (model 78D).

Unit pulses and EMG were recorded on a personal computer, using the 1401 plus interface and Spike 2 program (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). The rate of digitization was 372 Hz for EMG and 21 kHz for unit activity. Digital EMG integration was performed over 10-s epochs.

Microinjections

In each experiment, two to five injection sites in the medial medulla were sequentially tested, each with one OX-A microinjection. Sites were tested in random order. Subsequent microinjections were performed when muscle tone returned to background. OX-A (Peptide Institute, Osaka, Japan) was dissolved in 0.9% saline to obtain 50-μM concentration of OX-A. The solution was stored at 4°C for a maximum of 2 wk. Control saline microinjections (n = 16) into the medial medulla were performed in four rats. The PPTg and adjacent reticular formation were reversibly inactivated by unilateral or bilateral microinjections of lidocaine (4%). The OX-A and lidocaine injections consisted of 0.3 μl administrated at a rate of 10 nl/s. The effective radial spread of lidocaine was approximately 0.4 mm (Tehovnik and Sommer 1997). All injections were performed using a 1-μl Hamilton microsyringe and injecting cannulae with outside tip diameter of 0.2 mm.

Identification of mesopontine neurons related to muscle rigidity

Mesopontine reticular neurons related to rigid muscle tone were identified using the following criteria: 1) location in the dorsolateral mesopontine region where stimulation produces bilateral muscle tone facilitation (Lai and Siegel 1990a); 2) regular firing rate during postdecerebrate rigidity (Hoshino and Pompeiano 1976); 3) long duration (>1 ms) action potentials (Garcia-Rill et al. 1983); 4) positive correlation of firing rate with muscle tone during stimulation of inhibitory PnO sites that produced muscle tone suppression (Mileykovskiy et al. 2000); 5) firing rate resumption preceding muscle tone recovery; and 6) absence of firing rate change with passive manipulation of the hindlimbs (Garcia-Rill and Skinner 1988).

Histology

Cathodal current (0.1–0.2 mA, 4–6 s) was passed through the microelectrodes at the end of each recording track. Rats were deeply anesthetized by pentobarbital sodium (70 mg/kg ip) and perfused transcardially with 0.01 M PBS, pH 7.4, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS. Brains were removed and cut into 60-μm sections. The location of recorded neurons was determined by using the track made by the microelectrode, the depth of the marking lesion, and the depth measurements on the microdrive. The electrode tracks and marking lesions were visualized on a Nikon microscope and plotted with a Neurolucida interface according to the rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson 1997). Cannula tracks were visualized on a Leica MZ6.

Data analysis

The latency of muscle tone changes was measured from the start of the microinjection to either a 50% increase or a 50% decrease in nonintegrated EMG amplitude compared with baseline. The duration was calculated from the time of onset of sustained increase or decrease in muscle tone to the return of tone to baseline level. The latencies and durations were averaged for right and left hindlimbs for microinjections that produced bilateral muscle tone variations.

Unit firing rates were analyzed by Wilcoxon matched-pairs test. The average unit firing rates were calculated for 10 s before and during electrical stimulation, or after OX-A microinjections when sustained muscle tone facilitation was observed. Regression analysis was used for estimating the correlation between changes of mesopontine unit firing rate and integrated ipsilateral gastrocnemius EMG. We selected this hindlimb muscle because mesopontine units related to motor activity send mainly ipsilateral descending projections (Garcia-Rill and Skinner 1987b). The changes of integrated EMG and firing rate were calculated in percent of baseline level. All average values are means ± SE.

RESULTS

Identification of medullary sites producing muscle tone changes

Eighteen rats with postdecerebrate hindlimb EMG were used for identification of medullary sites producing muscle tone changes during electrical stimulation (30–100 μA, 10–15 s). Figure 1A shows the distribution of muscle tone facilitating sites, muscle tone inhibitory sites, and sites producing locomotion on frontal sections of the rat brain. Twenty-six sites located in the GiA and GiV produced bilateral facilitation of hindlimb muscle tone during electrical stimulation (Fig. 2A). Twenty-five medullary sites induced a contralateral hindlimb muscle tone increase, and 11 sites evoked ipsilateral muscle tone facilitation. Seven medial medullary sites produced only bilateral tibialis anterior muscle tone facilitation. Controlled hindlimb locomotion in rats (Fig. 2B) was recorded during electrical stimulation of four sites located in caudal GiA near the raphe magnus nucleus (Fig. 1 A). On the other hand, electrical stimulation of the DPGi sites (n = 7) and Gi sites (n = 5) produced bilateral hindlimb muscle tone suppression in rats with posdecerebrate muscle rigidity (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 1.

Coronal views of the rat medulla showing the location of sites producing changes of rigid hindlimb muscle tone in decerebrate rats during electrical stimulation (A) and after orexin-A (OX-A) microinjection (B). Stimulating currents, <100 μA, OX-A concentration, 50 μM. □, bilateral muscle tone facilitation; O, contralateral muscle tone facilitation; △, ipsilateral muscle tone facilitation; ◇, bilateral facilitation of only tibialis anterior muscles; ■, bilateral muscle tone suppression; •, hindlimb locomotion; ▲, hindlimbs jerks. GiA and GiV, gigantocellular reticular nucleus, alpha and ventral parts, respectively; Br, bregma.

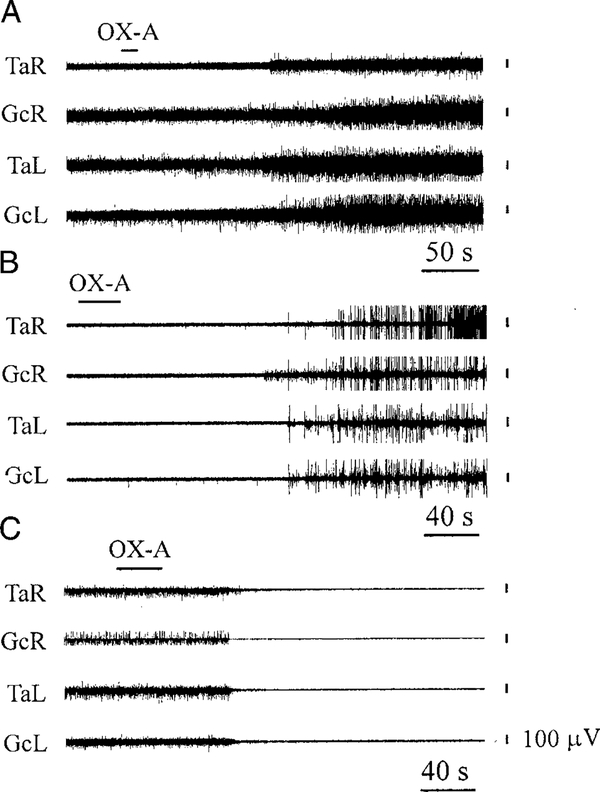

fig. 2.

Bilateral hindlimb muscle tone facilitation (A) and locomotion (B) during GiA electrical stimulation (R, right side). C: bilateral hindlimb muscle tone suppression during the Gi stimulation (R, right side). TaR, TaL, electromyogram (EMG) of tibialis anterior muscle (right and left side, respectively); GcR, GcL, EMG of gastrocnemius muscle (right and left side, respectively). Stimulating currents, <100 μA.

OX-A microinjections into the identified medullary sites

OX-A microinjections into 23 GiA sites, identified previously as bilateral facilitatory sites, produced a bilateral increase of hindlimb muscle tone (Figs. 1B and 3A). The latency of muscle tone facilitation ranged from 68 to 337 s, with a mean latency of 188 ± 14 s (mean ± SE, n = 23). The duration of muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjections into the GiA ranged from 232 to 1,180 s, with a mean duration of 697 ± 59 s (n = 23). OX-A microinjections into four GiA locomotor-inducing sites evoked bilateral hindlimb jerks in three cases (Fig. 3B) and ipsilateral hindlimb stepping (n = 1). The latency and duration of hindlimb jerks and stepping ranged from 74 to 162 s and from 491 to 1,612 s, respectively.

fig. 3.

Bilateral hindlimb muscle tone facilitation (A) and bilateral jerks (B) after OX-A microinjections into the GiA. C: bilateral hindlimb muscle tone inhibition after OX-A microinjections into the Gi. Top horizontal left bars indicate the time and duration of injections. See abbreviations in Fig. 2.

On the other hand, OX-A microinjections into the DPGi and Gi inhibitory sites (n = 11) produced bilateral muscle tone suppression (Fig. 3C). The latency of muscle tone suppression ranged from 16 to 140 s, with a mean of 73 ± 13 s (n = 11). The duration of muscle tone suppression varied from 156 to 682 s, with an average of 348 ± 62 s (n = 11). OX-A microinjections into previously selected GiV sites (n = 6), inducing bilateral muscle tone facilitation during electrical stimulation (Fig. 1A), produced weak (<50%) ipsilateral (n = 2) and bilateral (n = 1) increase of hindlimb EMG or were ineffective (n = 3). Control saline microinjections (n = 16) into the muscle tone facilitatory and inhibitory sites located in the GiA, GiV, DPGi, and Gi did not produce hindlimb muscle tone changes within the 1-h postinjection observation period.

Lidocaine microinjections into the dorsolateral mesopontine reticular formation

We hypothesized that the long-latency muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjections into the GiA and the low effectiveness of GiV microinjections could be related to the interaction of GiA intrinsic reticular neurons with pontine and mesencephalic structures, producing muscle tone facilitation. Our previous results showed that neurons located in the anatomic equivalent of the MLR are related to muscle tone facilitation in decerebrate rats (Mileykovskiy et al. 2000). Lidocaine microinjections into the PPTg and surrounding reticular formation were, therefore, performed in nine rats to determine the role of this region in muscle tone facilitation produced by OX-A microinjections into the GiA.

Unilateral lidocaine microinjections (n = 17) into the sites located in the PPTg and central part of the lateral parabrachial nucleus (LPBC) produced ipsilateral (n = 10), contralateral (n = 3) or bilateral (n = 4) hindlimb muscle tone suppression (Figs. 4 and 5, A and B). Ten lidocaine microinjections inhibited unilateral or bilateral muscle tone completely, and seven microinjections evoked a decrease of EMG amplitude by an average of 67 ± 3% (min = 59, max = 78, n = 7) compared with the baseline. The latency of muscle tone inhibition after lidocaine microinjections ranged from 92 to 294 s, with a mean of 172 ± 14 s (n = 17). The duration of muscle tone suppression ranged from 1,228 to 2,567 s, with a mean of 1,792 ± 85 s (n = 17). In contrast, unilateral lidocaine microinjections (n = 10) into the deep mesencephalic nucleus (DpMe) evoked ipsilateral or bilateral muscle tone facilitation (Fig. 5C). The latency and duration of muscle tone facilitation after injection into the DpMe ranged from 157 to 269 s, with a mean of 189 ± 10 s (n = 10), and from 926 to 2,135 s, with a mean of 1,607 ± 116 s (n = 10), respectively.

fig. 4.

Location of mesopontine sites suppressing and facilitating hindlimb muscle tone after lidocaine microinjections. □ and O, ipsilateral and bilateral muscle tone suppression, respectively; △, contralateral muscle tone suppression; × and ◇, ipsilateral and bilateral muscle tone facilitation. DpMe, deep mesencephalic nucleus; LPBC, lateral parabrachial nucleus, central part; PPTg, pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus; Br, bregma.

fig. 5.

Ipsilateral (A) and bilateral (B) muscle tone suppression and bilateral muscle tone facilitation (C) after unilateral lidocaine microinjections into the PPTg and DpMe, respectively. Top horizontal left bars indicate the time and duration of injections. See abbreviations in Fig. 2.

Fifteen sites located in the GiA and 4 sites located in the ventral part of the Gi and facilitating muscle tone during electrical stimulation were tested with OX-A microinjections to increase hindlimb muscle tone before and after 19 bilateral lidocaine microinjections into the PPTg and LPBC. In 12 cases, bilateral lidocaine microinjections decreased muscle tone bilaterally and prevented muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjections into the GiA (Fig. 6, A and B). Forty-five minutes after lidocaine administration, OX-A microinjections into the same GiA sites facilitated bilateral hindlimb muscle tone again (Fig. 6C). In four cases, bilateral lidocaine microinjections did not prevent hindlimb jerks with weak muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjections into the GiA. OX-A microinjections (n = 3) into the ventral part of the Gi, performed after lidocaine injections, suppressed hindlimb muscle tone if complete muscle atonia did not occur after bilateral lidocaine injections.

fig. 6.

Changes of hindlimb muscle tone after OX-A microinjections into the GiA site, facilitating muscle tone, performed before and after bilateral lidocaine microinjections into the PPTg. A: muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjection preceding lidocaine administration. B: bilateral lidocaine microinjections prevent muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjection. C: OX-A microinjection into the same GiA site again facilitates muscle tone in 45 min after bilateral lidocaine microinjections. Top horizontal bars indicate the time and duration of injections. See abbreviations in Fig. 2.

To determine whether the postdecerebrate muscle rigidity level and lidocaine-induced muscle tone decrease have a role in the OX-A facilitatory effect on muscle tone, we used a control group of decerebrate rats (n = 9) without muscle rigidity for experiments similar to those described above. We observed muscle tone facilitation after electrical stimulation and following OX-A microinjections into the GiA sites in five animals (Fig. 7A). The latency and duration of muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjections ranged from 122 to 193 s, with a mean of 159 ± 13 s (n = 5) and from 215 to 603 s, with a mean of 331 ± 71 s (n = 5), respectively. Bilateral lidocaine microinjections into dorsolateral mesopontine region prevented muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjections into these GiA sites for 30–40 min (Fig. 7B). However, OX-A microinjections performed at the same sites after this period evoked muscle tone facilitation (Fig. 7C).

fig. 7.

Changes of hindlimb muscle tone in rats with zero postdecerebrate rigidity after OX-A microinjections into the GiA site, facilitating muscle tone, performed before and after bilateral lidocaine microinjections into the PPTg. A: muscle tone facilitation during electrical stimulation and after OX-A microinjection preceding lidocaine administration. B: OX-A injected into the GiA does not evoke muscle tone facilitation after bilateral lidocaine microinjections. C: OX-A microinjection into the same GiA site again facilitates muscle tone in 45 min after lidocaine bilateral microinjections. Top horizontal bars indicate the time of electrical stimulation and duration of injections. See abbreviations in Fig. 2.

Influence of OX-A microinjections into the GiA on mesopontine neurons

To obtain additional evidence of participation of dorsolateral mesopontine region in muscle tone facilitation produced by OX-A microinjections into the GiA, discharges of 72 spontaneously active units were recorded in the PPTg and adjacent reticular formation in 6 rats. Eighteen neurons satisfied the criteria for cells related to rigid muscle tone. These neurons had an average firing rate of 13.0 ± 1.1 spike/s (n = 18, min = 4, max = 22) and a spike duration of 2.18 ± 0.05 ms (min = 1.9, max = 2.3) during muscle tone rigidity. Neurons were located mainly in the mesopontine region, producing muscle tone facilitation (Fig. 8, A and B), and were completely inhibited by PnO stimulation, suppressing muscle tone (Fig. 9, A and B). The firing rate resumption in these units preceded the muscle tone recovery after PnO stimulation by an average of 3.9 ± 0.2 s (n = 18, min = 2.8, max = 5.7). Passive manipulation of hindlimbs did not affect the activity of these mesopontine cells.

fig. 8.

Location of neurons related to rigid muscle tone (A) and muscle tone facilitation (B) during electrical stimulation of the PPTg and surrounding mesopontine reticular formation. Stimulating currents, <100 μA. PPTg, pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus; see other abbreviations in Fig. 2.

fig. 9.

Location of PnO sites suppressing hindlimb muscle tone bilaterally (A) and inhibition of PPTg neuron related to rigid muscle tone during electrical stimulation of the PnO inhibitory site. Stimulating currents, <100 μA. PnO, pontine reticular nucleus, oral part; PPTg(R), tonically active PPTg unit (right side); see other abbreviations in Fig. 2.

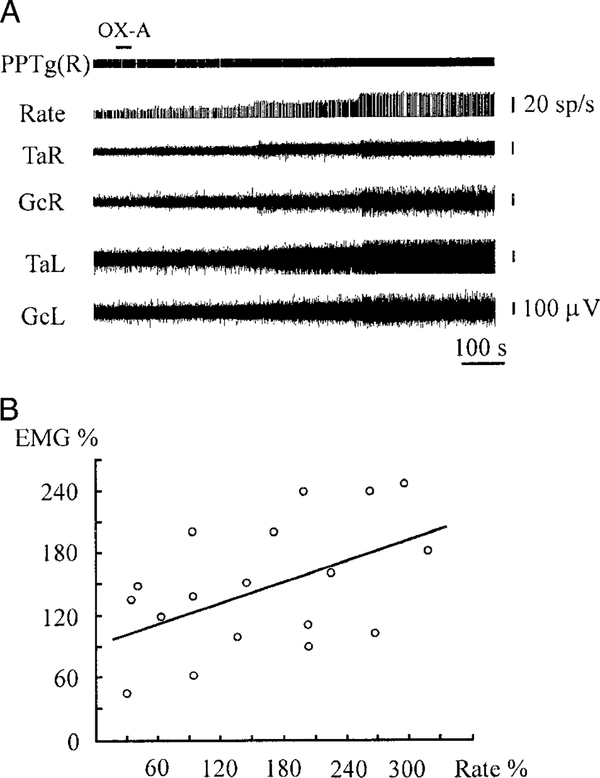

The firing rate of nine neurons related to rigid muscle tone was analyzed during OX-A microinjections into the nine GiA sites facilitating muscle tone. Excitation of these cells after OX-A microinjections preceded muscle tone facilitation by an average of 7.8 ± 1.1 s (n = 9, min = 3, max = 14). The discharge frequency of all cells was increased by an average of 185 ± 13% (n = 9, min = 115, max = 322, P < 0.01) compared with the baseline and correlated with muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjections (Fig. 10, A and B). The regression equation of gastrocnemius EMG on ipsilateral mesopontine unit firing rate after microinjections was EMG% = 94.6 + 0.33 Rate% (SE = 27.3, 0.15; t = 3.46, 2.26; df = 1, 16; P < 0.05). The correlation coefficient between gastrocnemius EMG and ipsilateral mesopontine unit firing rate was 0.49 (n = 18, P < 0.05).

fig. 10.

Excitation of PPTg neuron and muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjections into the GiA (A). Regression diagram (B) showing relationship between changes of gastrocnemius EMG (EMG%) and unit firing rate (Rate%) located in the dorsolateral mesopontine region. Top horizontal bar at the left indicates the time and duration of injection. See abbreviations in Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

The current study shows that medullary sites producing muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjections were mainly located in the GiA. Microinjections into the GiV did not produce significant muscle tone facilitation, although the neurons located in this nucleus receive a moderate orexinergic innervation (Peyron et al. 1998) and send axons to spinal cord as do the GiA neurons (Kinjo et al. 1990; Shen et al. 1990). Bilateral lidocaine microinjections into the PPTg and adjacent dorsolateral mesopontine reticular formation blocked muscle tone facilitation produced by OX-A microinjections into the GiA. Moreover, OX-A microinjections into the GiA produced excitation of neurons located in the dorsolateral mesopontine region and related to muscle tone facilitation. These findings suggest that muscle tone facilitation after OX-A microinjections into the GiA is related to ascending excitation by GiA neurons of pontine and mesencephalic structures facilitating muscle tone. There are several sites in the midbrain and pons where low-threshold electrical stimulation or chemical excitation can elicit stepping and muscle tone facilitation in decerebrate and intact animals. These sites coincide the PPTg, CnF, medial part of the periaqueductal gray, superior colliculus, lateral lemniscus, parabrachial nucleus, and pontomedullary locomotor strip (Bandler et al. 1991; Coles et al. 1989; Garcia-Rill and Skinner 1988; Parker and Sinnamon 1983; Sinnamon et al. 1987; Zhang et al. 1990). Some of these sites correspond with locomotor systems partly independent of MLR. In particular, stepping produced by hypothalamic stimulation requires an intact anterior dorsal tegmentum, anterior ventromedial midbrain, oral pontine reticular nucleus, and PPTg (Levy and Sinnamon 1990; Sinnamon and Benaur 1997). There are data that selective excitotoxic lesion of the CnF or PPTg does not evoke a locomotor deficit in freely behaving animals (Allen et al. 1996; Inglis et al. 1994a,b; Olmstead and Franklin 1994). In contrast, results presented by other authors do not support this point. Microinjections of cobalt chloride, which can block synaptic transmission, and application of toxic doses of excitatory amino acid into subregions of the MLR significantly decrease locomotion induced by dopamine injections into the nucleus accumbens or picrotoxin injections into the subpallidal region (Brudzynski et al. 1993). Locomotor activity elicited by injections of picrotoxin into the subpallidal region and amphetamine into the nucleus accumbens is reduced by administration of procaine into the PPTg (Brudzynski and Mogenson 1985; Mogenson and Wu 1988). Suppression of induced and spontaneous locomotion was obtained in the precollicular-post-mammilary decerebrate and decorticate animals after injections of muscimol, diazepam, and GABA into the MLR (Garcia-Rill et al. 1985; Pointis and Borenstein 1985). Locomotor activity induced by amphetamine applications into the nucleus accumbens is reduced by GABA injections into the MLR in freely moving animals (Brudzynski et al. 1986). Symmetric lesions of the LPBC also reduced motor activity in open field and labyrinth tests (Knupfer et al. 1988). The immunocytochemical staining of c-Fos protein in rats with chemically induced locomotion shows of activation of cells belonging to the PPTg, CnF, ventrolateral periaqueductal gray, and region of the dorsal tegmental bundle (Brudzynski and Wang 1996). These data indicate that neurons related to locomotion are widespread in the dorsolateral mesopontine region and explain how partial inactivation or destruction of MLR elements could be ineffective in blocking locomotion. In parallel with this, it is possible to conclude that the dorsolateral mesopontine region is a part of a distributed brain stem system controlling locomotor activity and, therefore, selective destruction of MLR subregions is not accompanied by lack of locomotion (Allen et al. 1996). We propose that muscle tone decrease after lidocaine microinjectins into the dorsolateral mesopontine region is related to elimination of numerous inputs to this distributed brain stem system in decerebrate animals. We found that the most effective sites for lidocaine blockade of muscle tone are in the caudal part of the PPTg and rostral division of the LPBC. The high effectiveness of these sites may be linked with lidocaine spreading in several areas participating in locomotion and muscle tone facilitation, in particular, in the PPTg, CnF, dorsal tegmental bundle, LPBC, and region under superior cerebellar peduncle.

In a recent study, we have reported that neurons located in the anatomic equivalent of the MLR participate in muscle tone facilitation in decerebrate rats. These cells are inhibited by electrical stimulation of PnO and Gi inhibitory sites, as well as by lumbar perivertebral pressure producing bilateral hindlimb muscle atonia (Mileykovskiy et al. 2000). We propose that PPTg, CnF, and dorsal PnO units participating in muscle tone facilitation (Juch et al. 1992; Lai and Siegel 1990a; Mileykovskiy et al. 2000) are excited by medioventral medullary neurons sending rostral projections (Steininger et al. 1992) and receiving orexinergic innervation. In turn, these midbrain and pontine muscle facilitating structures directly (Rye et al. 1988; Skinner et al. 1990a; Spann and Grofova 1989) or through medullary reticular neurons (Bayev et al. 1988; Garcia-Rill and Skinner 1987a,b; Hermann et al. 1997; Nakamura et al. 1990; Rye et al. 1988) excite spinal motor systems. The PPTg descending fibers terminate in the PnO, caudal pontine reticular nucleus, and in the GiA and GiV (Grofova and Keane 1991). Skinner et al. (1990b) reported that about 10% of cholinergic and a large number of noncholinergic PPTg neurons project to the medioventral medulla region related to locomotion. Descending projections from CnF sites producing locomotion were found in the ipsilateral Gi and magnocellular reticular nucleus (Steeves and Jordan 1984).

We also propose that noradrenergic neurons of the LC are activated during OX-A microinjections into the GiA. In our recent study, we reported excitation of 30% LC neurons during electrical stimulation of the medial medulla, especially of the medioventral medullary region (Mileykovskiy et al. 2000). Pharmacological, electrophysiological, and behavioral studies indicate an overall facilitatory action of norepinephrine on spinal motor systems (Holstege and Kuypers 1987; White and Neuman 1980, 1983). We have recently shown that microinjections of OX-A and OX-B in the vicinity of LC increase the activity of noradrenergic neurons and produce a correlated facilitation of muscle tone in decerebrate rats (Kiyashchenko et al. 2001).

Electrical stimulation and chemical excitation of the medioventral medulla produce locomotor activity in decerebrate cats and rats (Garcia-Rill and Skinner 1987a; Kinjo et al. 1990). However, we did not observe significant hindlimb stepping as a result of OX-A microinjections into this region. We propose that the excitatory effect of OX-A microinjections into the GiA is not sufficient for induction of locomotion in decerebrate rats. This result suggests that this peptide has a modulating rather than a triggering role in phasic motor regulation.

We have observed hindlimb muscle tone suppression as a result of OX-A microinjections into the medial division of the DPGi and Gi. We recently reported similar inhibitory motor effects after microinjections of OX-A and OX-B in PnO sites, producing muscle tone suppression during electrical stimulation (Kiyashchenko et al. 2001). These pontine and medullary structures receive a relatively low level of orexinergic innervation (Peyron et al. 1998). However, they are very effective inhibitors of muscle tone. The PnO, DPGi, and Gi are the main parts of a brain stem–reticulospinal inhibitory system hyperpolarizing spinal motoneurons (Jankowska et al. 1968; Magoun and Rhines 1946; Takakusaki et al. 1989, 1993, 1994). The DPGi and Gi receive excitatory inputs from the medial and dorsolateral pontine inhibitory regions (Mileikovskii 1994; Takakusaki et al. 1989, 1994) and participate in induction of REM sleep atonia (Chase and Morales 1990; Lai and Siegel 1990a,b; Sakai et al. 1979; Schenkel and Siegel 1989). Electrical stimulation of the DPGi and Gi sites inhibits the discharge in 70% of noradrenergic LC cells and suppresses neuron activity linked to muscle tone facilitation in the anatomical equivalent of the MLR (Mileykovskiy et al. 2000).

Muscle tone facilitation after lidocaine inactivation of the DpMe suggests that neuronal populations modulating activity of the pontine and medullary inhibitory structures are located in the rostral brain stem and forebrain. Electrical and chemical stimulation (kainic acid) of the medial part of the midbrain reticular formation, lateral division of the parafascicular thalamic nucleus, and deep layers of the frontoparietal cortex block the motor activity in freely moving rats and suppress the hindlimb muscle tone induced by hypothalamic and red nucleus stimulation in anesthetized animals (Mileikovskii et al. 1991; Mileikovsky et al. 1994).

Thus, our results, combined with our recent data showing muscle tone facilitation after OX microinjections in the LC (Kiyashchenko et al. 2001), support the hypothesis that orexins participate in muscle tone regulation at the brain stem level. We propose that the GiA is an important brain stem target for OX influences on spinal muscle tone facilitatory systems. The loss of OX function in human narcoleptics (Peyron et al. 2000; Thannical et al. 2000) may decrease the activity of these brain stem structures facilitating muscle tone and allow the phasic motor inhibition elicited by emotion to cause a loss of muscle tone (Siegel 1999).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-41370 and HL-60296 and by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- Allen LF, Inglis WL, and Winn P. Is the cuneiform nucleus a critical component of the mesencephalic locomotor region? An examination of the effects of excitotoxic lesions of the cuneiform nucleus on spontaneous and nucleus accumbens induced locomotion. Brain Res Bull 41: 201–210, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandler R, Carrive P, and Zhang SP. Integration of somatic and autonomic reactions within the midbrain periaqueductal grey: viscerotopic, somatotopic and functional organization. Prog Brain Res 87: 269–305, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayev KV, Beresovskii VK, Kebkalo TG, and Savoskina LA. Afferent and efferent connections of brainstem locomotor regions: study by means of horseradish peroxidase transport technique. Neuroscience 26: 871–891, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOURGIN P, HUITRON-RESENDIZ S, SPIER AD, FABRE V, MORTE B, CRIADO JR, SUTCLIFF JG, HENRIKSEN SJ, AND DE LECEA L Hypocretin-1 modulates rapid eye movement sleep through activation of locus coeruleus neurons. J Neurosci 20: 7760–7765, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUDZYNSKI SM, HOUGHTON PE, BROWNLEE RD, AND MOGENSON GJ. Involvement of neuronal cell bodies of the mesencephalic locomotor region in the initiation of locomotor activity of freely behaving rats. Brain Res Bull 16: 377–381, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUDZYNSKI SM AND MOGENSON GJ. Association of the mesencephalic locomotor region with locomotor activity induced by injections of amphetamine into the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res 334: 77–84, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUDZYNSKI SM AND WANG D C-Fos immunohistochemical localization of neurons in the mesencephalic locomotor region in the rat brain. Neuroscience 75: 793–803, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUDZYNSKI SM, WU M, AND MOGENSON GJ. Decrease in rat locomotor activity as a result of changes in synaptic transmission to neurons within the mesencephalic locomotor region. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 71: 394–406, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHASE MH AND MORALES FR. The atonia and myoclonia of active (REM) sleep. Annu Rev Psychol 209: 557–584, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEMELLI RM, WILLIE JT, SINTON CM, ELMQUIST JK, SCAMMELLI T, LEE C, RICHARDSON JA, WILLIAMS SC, XIONG Y, KISANUKI Y, FITCH TE, NAKAZATO M, HAMMER RE, SAPER CB, AND YANAGISAWA M. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell 98: 437–451, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLES SK, ILES JF, AND NICOLOPOULOS-STOURNARAS S The mesencephalic centre controlling locomotion in the rat. Neuroscience 28: 149–157, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE LECEA L, KILDUFF TS, PEYRON C, GAO XB, FOYE PE, DANIELSON PE, FUKUHARA C, BATTENBERG ELF, GAUTVIK VT, BARTLETT FS II, FRANKEL WN, VAN DEN POL AN, BLOOM FE, GAUTVIK KM, AND SUTCLIFFE JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamic-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 322–327, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA-RILL E AND SKINNER RD. The mesencephalic locomotor region. 1. Activation of medullary projection site. Brain Res 411: 1–12, 1987a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA-RILL E AND SKINNER RD. The mesencephalic locomotor region. 2. Projections to reticulospinal neurons. Brain Res 411: 13–20, 1987b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA-RILL E AND SKINNER RD. Modulation of rhythmic function in the posterior midbrain. Neuroscience 27: 639–654, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA-RILL E, SKINNER RD, CONRAD C, MOSLEY D, AND CAMPBELL C. Projections of the mesencephalic locomotor region in the rat. Brain Res Bull 17: 33–40, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA-RILL E, SKINNER RD, AND FITZGERALD JA. Chemical activation of mesencephalic locomotor region. Brain Res 330: 43–54, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA-RILL E, SKINNER RD, GILMORE SA, AND OWINGS R Connections of the mesencephalic locomotor region (MLR). 2. Afferents and efferents. Brain Res Bull 10: 63–71, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROFOVA I AND KEANE S Descending brainstem projections of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus in the rat. Anat Embriol (Berl) 184: 275–290, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAGAN JJ, LESLIE RA, PATEL S, EVANS ML, WATTAM TA, HOLMES S, BENHAM CD, TAYLOR SG, ROUTLEDGE C, HEMMATI P, MUNTON RP, ASHMEADE TE, SHAH AS, HATHER JP, HATHER PD, JONES DNC, SMITH MI, PIPER DC, HUNTER AJ, PORTER RA, AND UPTON N. Orexin A activates locus coeruleus cell firing and increases arousal in the rat. Neurobiology 96: 10911–10916, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAJNIK T, LAI YY, AND SIEGEL JM. Atonia related regions in the rodent pons and medulla. J Neurophysiol 84: 1942–1948, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERMANN DM, LUPPI PH, PEYRON C, HINKEL P, AND JOUVET M. Afferent projections to the rat nuclei raphe magnus, raphe pallidus and reticularis gigantocellularis pars alpha demonstrated by iontophoretic application of choleratoxin (subunit b). J Chem Neuroanat 13: 1–21, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLSTEGE JC AND KUYPERS HG. Brainstem projections to spinal motoneurons: an update. Neuroscience 23: 809–821, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORVATH TL, PEYRON C, DIANO S, IVANOV A, ASTON-JONES G, KILDUFF TS, AND VAN DEN POL AN. Hypocretin (orexin) activation and synaptic innervation of locus coeruleus noradrenergic system. J Comp Neurol 415: 145–159, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOSHINO K AND POMPEIANO O Selective discharge of pontine neurons during the postural atonia produced by an anticholinesterase in the decerebrate cat. Arch Ital Biol 114: 244–247, 1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INGLIS WL, ALLEN LF, WHITELAW RB, LATIMER M, BRACE HM, AND WINN P. An investigation into the role of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus in the mediation of locomotion and orofacial steretypy induced by d-amphetamine and apomorphine in the rat. Neuroscience 58: 817–833, 1994a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INGLIS WL, DUNBAR JS, AND WINN P Outflow from the nucleus accumbens to the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus: a dissociation between locomotor activity and the acquisition of responding for conditioned reinforcement stimulated by d-amphetamine. Neuroscience 62: 51–64, 1994b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANKOWSKA E, LUND S, LUNDBERG A, AND POMPEIANO O Inhibitory effect evoked through ventral reticulospinal pathways. Arch Ital Biol 106: 124–140, 1968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHN J, WU MF, AND SIEGEL JM. Systemic administration of hypoctretin-1 reduces cataplexy and normalizes sleep and waking durations in narcoleptic dogs. Sleep Res Online 3: 23–28, 2000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUCH PJ, SCHAAFSMA A, AND VANWILLIGEN JD. Brainstem influences on biceps reflex activity and muscle tone in the anaesthetized rat. Neurosci Lett 140: 37–41, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KINJO N, ATSUTA Y, WEBBER M, KYLE R, SKINNER RD, AND GARCIA-RILL E Medioventral medulla-induced locomotion. Brain Res Bull 24: 509–516, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIYASHCHENKO LI, MILEYKOVSKIY BY, LAI YY, AND SIEGEL JM. Increased and decreased muscle tone with orexin (hypocretin) microinjections in the locus coeruleus and pontine inhibitory area. J Neurophysiol 85: 2008–2016, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNUPFER M, WITTER S, AND KLINBERG F. Lesions in the mesencephalic reticular formation change open field and thirst motivated labyrinth behaviour of rats. Biomed Biochim Acta 47: 39–49, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOHYAMA J, LAI YY, AND SIEGEL JM. Inactivation of the pons blocks medullary-induced muscle tone suppression in the decerebrate cat. Sleep 21: 695–699, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAI YY AND SIEGEL JM. Muscle tone suppression and stepping produced by stimulation of midbrain and rostral pontine reticular formation. J Neurosci 10: 2727–2734, 1990a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAI YY AND SIEGEL JM. Cardiovascular and muscle tone changes produced by microinjection of cholinergic and glutamatergic agonists in dorsolateral pons and medial medulla. Brain Res 514: 27–36, 1990b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVY DI AND SINNAMON HM. Midbrain areas required for locomotion initiated by electrical stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus in the anesthetized rat. Neuroscience 39: 665–674, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN L, FARACO J, LI R, KADOTANI H, ROGERS W, LIN X, QIU X, DE JONG PJ, NISHINO S, AND MIGNOT E The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell 98: 365–376, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUBKIN M AND STRICKER-KRONGRAD A Independent feeding and metabolic actions of orexins in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 253: 241–245, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGOUN HW AND RHINES R An inhibitory mechanism in the bulbar reticular formation. J Neurophysiol 9: 165–171, 1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILEIKOVSKII BY, VEREVKINA SK, AND NOZDRACHEV AD. Central neurophysiological mechanisms of the regulation of inhibition. Neurosci Behav Physiol 21: 263–268, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILEIKOVSKII BYU. Influence of stimulation of movement-inhibiting areas of the pons on the activity of neurons of the medial region of the medulla oblongata. Neurosci Behav Physiol 24: 423–428, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILEIKOVSKY BY, VEREVKINA SV, AND NOZDRACHEV AD. Effects of stimulation of the frontoparietal cortex and parafascicular nucleus on locomotion in rats. Physiol Behav 55: 267–271, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILEYKOVSKIY BY, KIYASHCHENKO LI, KODAMA T, LAI YY, AND SIGEL JM. Activation of pontine and medullary motor inhibitory regions reduces discharge in neurons located in the locus coeruleus and the anatomical equivalent of the midbrain locomotor region. J Neurosci 20: 8551–8558, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILNER KL AND MOGENSON GJ. Electrical and chemical activation of the mesencephalic and subthalamic locomotor regions in freely moving rats. Brain Res 452: 273–285, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOGENSON GJ AND WU M Differential effects on locomotor activity of injections of procaine into mediodorsal thalamus and pedunculopontine nucleus. Brain Res Bull 20: 241–246, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORIGUCHI T, SAKURAI T, NAMBU T, YANAGISAWA M, AND GOTO K Neurons containing orexin in the lateral hypothalamic area of the adult rat brain are activated by insulin-induced acute hypoglycemia. Neurosci Lett 264: 101–104, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA T, URAMURA K, NAMBU T, YADA T, GOTO K, YANAGISAWA M, AND SAKURAI T. Orexin-induced hyperlocomotion and stereotypy are mediated by the dopaminergic system. Brain Res 873: 181–187, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA Y, KUDO M, AND TOKUNO H Monosynaptic projection from pedunculopontine tegmental nuclear region to the reticulospinal neurons of the medulla oblongata. An electron microscope study in the cat. Brain Res 524: 353–356, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAMBU T, SAKURAI T, MIZUKAMI K, HOSOYA Y, YANAGISAWA M, AND GOTO K Distribution of orexin neurons in the adult rat brain. Brain Res 827: 243–260, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHINO S, RIPLEY B, OVEREEM S, LAMMERS GJ, AND MIGNOT E. Hypocretin (orexin) deficiency in human narcolepsy. Lancet 355: 39–40, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOWAK KW, MACKOWIAK P, SWITONSKA MM, FABIS M, AND MALENDOWICZ LK. Acute orexin effects on insulin secretion in the rat: in vivo and in vitro studies. Life Sci 66: 449–454, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLMSTEAD MCAND FRANKLIN KB. Lesions of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus block drug-induced reinforcement but not amphetamine-induced locomotion. Brain Res 638: 29–35, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARKER SM AND SINNAMON HM. Forward locomotion elicted by electrical stimulation in the diencephalon and mesencephalon of the awake rat. Physiol Behav 31: 581–587, 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAXINOS GAND WATSON C The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- PEYRON C, FARACO J, ROGERS W, RIPLEY B, OVEREEM S, CHARNAY Y, NEVSIMALOVA S, ALDRICH M, REYNOLDS D, ALBIN R, LI R, HUNGS M, PEDRAZZOLI M, PADIGARU M, KUCHERLAPATI M, FAN J, MAKI R, LAMMERS GJ, BOURAS C, KUCHERLAPATI R, NISHINO S, AND MIGNOT E. A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains. Nature Med 6: 991–997, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEYRON C, TIGHE DK, VAN DEN POL AN, DE LECEA L, HELLER HC, SUTCLIFFE JG, AND KILDUFF TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci 18: 9996–10015, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POINTIS D AND BORENSTEIN P The mesencephalic locomotor region in cat: effects of local applications of diasepam and gamma-aminobutyric acid. Neurosci Lett 53: 297–302, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PU S, JAIN MR, KALRA PS, AND KALRA SP. Orexins, a novel family of hypothalamic neuropeptides, modulate pituitary luteizing hormone secretion in an ovarian steroid-dependent manner. Regul Pept 78: 133–136, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RYE DB, LEE HJ, SAPER CB, AND WAINER BH. Medullary and spinal efferents of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus and adjacent mesopontine tegmentum in the rat. J Comp Neurol 269: 315–341, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAKAI K, SASTRE JP, SALVERT D, TOURET M, TOHYAMA M, AND JOUVET M. Tegmentoreticular projections with special references to the muscular atonia during paradoxical sleep in the cat: an HRP study. Brain Res 176: 233–254, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAKURAI T, AMEMIYA A, ISHII M, MATSUZAKI I, WILLIAMS SC, RICHARDSON JA, KOZLOVSKI GP, WILSON S, ARCH SJR, BUCHINGAM RE, HAYNES AC, CARR SA, ANNAN RS, MCNULTY DE, LIU WS, TERRETT JA, ELSHOURBAGY NA, BERGSMA DJ, AND YANAGISAWA M Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein–coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 92: 573–585, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMSON WK, GOSNELL B, CHANG JK, RESCH ZT, AND MURPHY TC. Cardiovascular regulatory actions of the orexins in brain. Brain Res 831: 248–253, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHENKEL E AND SIEGEL JM. REM sleep without atonia after lesions of the medial medulla. Neurosci Lett 98: 159–165, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEN P, ARNOLD AP, AND MICEVYCH PE. Supraspinal projections to the ventromedial lumbar spinal cord in adult male rats. J Comp Neurol 300: 263–272, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIEGEL JM. Narcolepsy: a key role for hypocretins. Cell 98: 409–412, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINNAMON HM AND BENAUR M GABA injected into the anterior dorsal tegmentum (ADT) of the midbrain blocks stepping initiated by stimulation of the hypothalamus. Brain Res 766: 271–275, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINNAMON HM, GINZBURG RN, AND KUROSE GA. Midbrain stimulation in the anesthetized rat: direct locomotor effects and modulation of locomotion produced by hypothalamic stimulation. Neuroscience 20: 695–707, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKINNER RD AND GARCIA-RILL E The mesencephalic locomotor region (MLR) in the rat. Brain Res 323: 385–389, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKINNER RD, KINJO NV, HENDERSON V, AND GARCIA-RILL E Locomotor projections from the pedunculopontine nucleus to the spinal cord. Neuroreport 1: 183–186, 1990a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKINNER RD, KINJO N, ISHIKAWA Y, BIEDERMAN JA, AND GARCIA-RILL E. Locomotor projections from pedunculopontine nucleus to the medioventral medulla. Neuroreport 1: 207–210, 1990b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPANN BM AND GROFOVA I Origin of ascending and spinal pathways from the nucleus tegmenti pedunculopontinus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 283: 13–27, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEEVES JD AND JORDAN LM. Autoradiogrphic demonstration of the projections from the mesencephalic locomotor region. Brain Res 307: 263–276, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEININGER TL, RYE DB, AND WAINER BH. Afferent projections to the cholinergic pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus and adjacent midbrain extrapyramidal area in the albino rat. 1. Retrograde tracing studies. J Comp Neurol 321: 515–543, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWEET DC, LEVINE AS, BILLINGTON CJ, AND KOTZ CM. Feeding response to central orexins. Brain Res 821: 535–538, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAHASHI N, OKUMURA T, YAMADA H, AND KOHGO Y Stimulation of gastric acid secretion by centrally administered OX-A in conscious rats. Biochem Biophys Commun 254: 623–627, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAKUSAKI K, MATSUYAMA K, KOBAYASHI Y, KOHYAMA J, AND MORI S. Pontine microinjection of carbachol and critical zone for inducing postural atonia in reflexively standing decerebrate cats. Neurosci Lett 153: 185–188, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAKUSAKI K, OHTA Y, AND MORI S. Single medullary reticulospinal neurons exert postsynaptic inhibitory effect via inhibitory interneurons upon alphamotoneurons innervating cat hindlimb muscles. Exp. Brain Res 74: 11–23, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAKUSAKI K, SHIMODA N, MAYSUYAMA K, AND MORI S. Discharge properties of medullary reticulospinal neurons during postural changes induced by intrapontine injections of carbachol, atropine and serotonin, and their functional linkages to hindlimb motoneurons in cats. Exp Brain Res 99: 361–374, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEHOVNIK EJ AND SOMMER MA. Effective spread and time course of neural inactivation caused by lidocaine injection in monkey cerebral cortex. J Neurosci Methods 74: 17–26, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THANNICAL TC, MOORE RY, NIENHUIS R, RAMANATHAN L, GULYANI S, ALDRICH M, CORNFORD M, AND SIEGEL JM. Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron 27: 469–474, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITE SR AND NEUMAN RS. Facilitation of spinal motoneuron excitability by 5-hydroxytryptamine and noradrenaline. Brain Res 188: 119–127, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITE SR AND NEUMAN RS. Pharmacological antagonism of facilitatory but not inhibitory effects of serotonin and norepinephrine on excitability of spinal motoneurons. Neuropharmacology 22: 489–494, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS G, HARROLD JA, AND CUTLER DJ. The hypothalamus and the regulation of energy homeostasis: lifting the lid on a black box. Proc Nutr Soc 59: 385–396, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU M-F, GULYANI SA, YAU E, MIGNOT E, PHAN B, AND SIEGEL JM. Locus coeruleus neurons: cessation of activity during cataplexy. Neuroscience 91: 1389–1399, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XI M, MORALES FR, AND CHASE MH. Effects on sleep and wakefulness of the injection of hypocretin-1 (orexin-A) into the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus of the cat. Brain Res 901: 259–264, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG SP, BANDLER R, AND CARRIVE P. Flight and immobility evoked by excitatory amino acid microinjection within distinct parts of the subtentorial midbrain periaqueductal gray of the cat. Brain Res 520: 73–82, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]