Abstract

Regular physical activity can increase joint stability and function, reduce the risk of injury, and improve quality of life of people with haemophilia (PwH). However, a recent review of the literature shows that appropriate physical activity and sport are not always promoted enough in the overall management of PwH. A group of Italian experts in haemophilia care undertook a consensus procedure to provide practical guidance on when and how to recommend physical exercise programmes to PwH in clinical practice. Three main topics were identified –haemophilia and its impact on movement, physical activity recommendations for PwH, and choice and management of sports activity in PwH– and ten statements were formulated. A modified Delphi approach was used to reach a consensus. The group also created practical tools proposing different physical activities and frequencies for different age groups, the Movement Pyramids, to be shared and discussed with patients and caregivers. In conclusion, in the opinion of the working group, physical activity can be considered as a low-price intervention that can prevent/reduce the occurrence of chronic diseases and should be further encouraged in PwH to obtain multiple physical and psychological benefits. Future research should include prospective studies focusing on participation in sports, specific risk exposure and clinical outcomes.

Keywords: haemophilia, physical activity, sports, recommendations

INTRODUCTION

In people with haemophilia (PwH), especially those with severe disease, haemorrhages frequently affect joints. The recurrence of haemarthrosis progressively impairs joint function, leading to chronic arthropathy, which may, in turn, result in disability. It is recognized that physical fitness has several benefits in PwH. According to the World Federation of Haemophilia (WFH) recommendations, physical activity can improve patients’ quality of life and clinical outcomes deriving from the advancement of prophylaxis1. Regular physical activity can increase joint stability and function and reduce the risk of injury2–5. The WFH guidelines recommend adapted physical activity –which reflects the individual’s preferences and interests, age, physical condition, and ability– to promote normal neuromuscular development and physical fitness4. Several recent papers have reported that PwH are as active as the general population. A very recent review aimed at systematically assessing the available data regarding levels of physical activity among PwH showed that physical activity levels varied greatly among heterogeneous samples of PwH5. Therefore it seems that the necessity of physical exercise is not yet emphasized sufficiently. In Italy, in the authors’ experience, appropriate physical activity and sport are not always adequately encouraged in the overall management of PwH and too many PwH have low-to-no physical activity. On this background, a group of Italian experts in haemophilia care decided to undertake a consensus procedure (the Movement for persons with haEMOphilia, MEMO, project), in order to provide practical guidance, suitable for Italian clinical practice, on when and how to recommend physical exercise programmes to PwH, to be tailored to the individual’s disease severity, treatment, age, and physical abilities. The MEMO scientific committee was composed of 11 Italian experts in haemophilia care, representing haemophilia centres located throughout Italy. Before starting the consensus procedure, a restricted group of members of the scientific committee met in the first quarter of 2020, to discuss the main evidence from the literature in the field and their personal clinical experience. During that first meeting, the main topics of the consensus were defined: (i) haemophilia and its impact on movement, (ii) physical activity recommendations for PwH, and (iii) choice and management of sporting activity for PwH. In addition, the following premises were agreed upon.

PREMISES

Severe haemophilia is characterised by generally frequent intra-articular bleeding (haemarthrosis) and muscle haematomas, which may be post-traumatic and sometimes spontaneous or not clearly attributable to traumatic events. Moderate haemophilia usually presents with rarer spontaneous bleeding and acute bleeding events are often secondary to trauma, surgery or invasive manoeuvres, although in some cases patients with moderate haemophilia experience several joint bleeds and significant joint impairment like those with severe disease6. Mild haemophilia very rarely gives rise to spontaneous haemarthrosis but rather causes post-traumatic or post-surgical bleeding or bleeding secondary to invasive manoeuvres (e.g., tooth extractions)4,7.

Joint and muscle haemorrhages are the main distinctive clinical signs of haemophilia. Impairment of the musculoskeletal system balance induced by recurrent haemarthrosis and the onset of a chronic degenerative arthropathy can lead to deficiencies in muscle strength, motor coordination and proprioception, as well as muscle atrophy, contractures, and joint instability. As a consequence, chronic pain and functional impairment up to disability may arise, with a major impact on patients’ quality of life (QoL) and possibility of participating in social life4,8–11.

Promoting the health of PwH does not only mean establishing pharmacological programmes for the prevention/reduction of the impact of chronic arthropathy (primary, secondary, and tertiary prophylaxis) but also means intervening on the people’s behaviours and promoting the adoption of active lifestyles4,10,12.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that children, adolescents, and adults perform regular physical activity of at least moderate intensity and exercises to strengthen the musculoskeletal system several times a week, depending on age13; PwH are not exempt from these recommendations4,9,14,15.

METHODS

The consensus procedure involved a modified Delphi approach, which is an established method to reach a consensus opinion among a group of experts in a particular field and is often used to produce best-practice guidelines16–18. All the meetings were virtual due to the lockdown established following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the second quarter of 2020 the scientific committee met to discuss and formulate the statements. Ten statements were formulated using the discussion methodology. The initiative was then presented by the scientific committee at the National Congress of the Italian Association of Haemophilia Centres (AICE) held in Milan and AICE members (n=142) were invited to participate in the first round of voting on a web platform with access through the AICE website where the premises and statements were uploaded. Voters were instructed to simply review the premises and rate their level of agreement with the ten proposed statements using a nine-point numerical rating scale (1=do not agree at all, 9=completely agree). A period of 1 month was allowed for voting. At the close of the first round of voting, the votes were analysed, and mean values were calculated. In the fourth quarter of 2020, first-round voters were invited to a final consensus virtual meeting with the SC, during which the first-round results were presented and discussed. Statements were first voted again as they were (second round of voting), then discussed and amended if required based on the discussion. If amendments were made, a third vote took place, and this was the final one. The statements achieving a final average score ≥7 were considered approved; statements for which a mean score ≥7 could not be reached despite discussion and amendments, had to be considered rejected. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic emergency, it was extremely difficult to bring all the voters together in the final virtual consensus meeting. Therefore, the first-round voters who were not able to participate in the meeting in whole or in part were asked to complete their voting on the web platform within 48 hours after the end of the meeting.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

At the first round of voting, there were 65 online voters (approximately 46% of the invited haemophilia specialists). Of these, 29 also voted online at the second round, 22 during the final consensus virtual meeting and seven within 48 hours after the meeting. The 36 missing voters at the second round were contacted prior to the consensus meeting but justified their absence by their full hospital commitments due to the worsening pandemic or by non-deferrable commitments that had occurred in the meantime. To the 29 experts who expressed their final level of consensus on the statements, the 11 members of the scientific committee should be added, for a total of 40 final voters. The list of the statements with the mean ratings obtained at the three voting rounds is reported in Table I. At the first round of voting, all statements achieved agreement (mean value ≥7). However, for most of them there was discussion on how to rephrase the statement more completely and appropriately. Following discussion and amendments, the level of consensus was further increased for almost all of the statements.

Table I.

Consensus statements on physical activity and sports in people with haemophilia

| Statement | 1st roundrating – 65 voters(mean value) | 2nd roundrating – 40 voters(mean value) | Final rating* (mean value) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Persons with haemophilia (PwH) have a higher risk of chronic arthropathy as a result of repeated joint bleeding. Revised as: 1. People with haemophilia, particularly those with severe haemophilia, have a higher risk of chronic arthropathy as a result of repeated joint bleeding. |

8.7 | 6.5 | 8.2 |

|

2. PwH, as a result of hypomobility and the excessive protection implemented, especially in children, by their parents, have an increased risk of obesity which enhances the risk of the onset of alterations in musculoskeletal functions. Revised as: 2. Poor physical activity and possible parental overprotection of children contribute to the risk of obesity and the onset of alterations in musculoskeletal functions. |

7.5 | 7.6 | 8.2 |

|

3. Strength, flexibility, and coordination are important for improving joint stability and function, increasing bone density and reducing the risk of bleeding. Revised as: 3. Movement coordination, muscle strength and flexibility are important for improving joint function and stability, preserving bone density, and reducing the risk of bleeding. |

8.5 | 8.3 | 8.5 |

|

4. Regular physical activity improves joint stability and function, can reduce the risk of acute bleeding episodes and the consequent complications and overall improves the QoL and interpersonal skills of the person with haemophilia. Revised as: 4. Regular physical activity enhances joint function and stability and can reduce the risk of acute bleeding episodes and related complications, thus overall improving the quality of life and interpersonal skills of the person with haemophilia. |

8.3 | 8.4 | 8.7 |

| 5. In people with haemophilia with a good joint condition, such as to allow them normal activity or involve only minimal limitations, motor skills must be progressively aligned with those of their healthy peers. | 8.0 | 8.4 | 8.3 |

| 6. In adults with arthropathy and the elderly, the risk of trauma/falls is increased due to structural and/or functional joint instability, resulting in an increased risk of injury, head trauma and intracranial haemorrhage. In these cases, instability should be minimised through personalised physiotherapy programmes. | 8.3 | 8.8 | 8.6 |

|

7. Haemophiliacs with inhibitor should also be encouraged to carry out regular physical activity, but with particular caution and timely monitoring of the effectiveness of the prophylaxis for the prevention of acute bleeding events, so that physical activity is conducted in total safety. Revised as: 7. People with haemophilia with inhibitors should also be encouraged to carry out regular physical activity, but with particular caution and timely monitoring of the effectiveness of prophylaxis for the prevention of acute bleeding events, so that physical activity is conducted safely. |

8.2 | 8.6 | 8.8 |

| 8. The choice of the type of sport to be practised should derive from a shared consensus between a multidisciplinary team composed of haematologists, specialists in the management of disorders of the musculoskeletal system (orthopaedists, physiatrists, physiotherapists), and specialists in sports medicine. The last will have the task of helping people with haemophilia to choose the sporting activity that best suits their physical conditions and assessing the absence of contraindications including those not related to haemophilia, also taking into account the wishes and expectations of the individual. | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.6 |

|

9. It is desirable that the multidisciplinary team promotes motor activity in PwH from the paediatric age and helps the individual to identify the most appropriate type of sport, in order to avoid subsequently limiting the practice of a particular sport following injuries, acute bleeding episodes, or requests for excessive performance, which could lead to frustration or even the complete refusal to practise any form of physical and sporting activity. Revised as: 9. It is desirable that the multidisciplinary team promotes motor activity in people with haemophilia since childhood and helps the individual to identify the most appropriate type of sport, also taking into account the potential risks, in order to avoid imposing subsequent limitations, which could cause frustration or even the patient’s complete refusal to practise any form of physical activity or sport. |

8.4 | 7.7 | 8.5 |

|

10. The task of the specialists of the haemophilia centres is to optimise the replacement therapy, taking into account the risks related to the sporting practice of the individual. Revised as: 10. One of the tasks of the specialists of a haemophilia centre is to optimise the anti-haemorrhagic prophylaxis, taking into account the risks related to the sporting practice of the individual. |

8.6 | 8.3 | 8.7 |

The third round of voting includes the seven online voters (who did not participate in the consensus meeting or in the discussion)

STATEMENTS

Each approved final statement is presented and discussed hereafter.

Topic 1 – Haemophilia and its impact on movement

-

1. People with haemophilia, particularly those with severe haemophilia, have a higher risk of chronic arthropathy as a result of recurrent joint bleeding.

The latest WHF guidelines underline the high risk of haemophilic arthropathy, which can result from recurrent bleeds but even from a single bleed4, evolving from haemarthrosis to chronic synovitis, progressive erosion of the articular surface, chronic haemophilic arthropathy, and eventually reaching joint destruction19,20. During the discussion, it was agreed that this occurs more frequently in patients with severe disease6, so this specification, initially absent, was added to the statement.

-

2. Poorphysical activity andpossible parental over protection of children contribute to the risk of obesity and the onset of alterations in musculoskeletal functions.

Overweight or obesity is an increasing problem in PwH, with the prevalence currently being higher than in previous generations. Rates are now similar to and, in certain subsets even higher than, those in the general population21. A 31% estimated pooled prevalence of overweight/obesity in European and North American PwH has been reported for the period 2003–201822. A recent German study documented a prevalence of overweight and obesity of 25.2% among 254 patients aged <30 years with severe haemophilia A and without a history of inhibitors23. The impact of obesity on joint bleeding, pain, and function and on QoL is recognized24 and it has been shown that some individuals experience reduced joint bleeds following even moderate weight loss25. Prevention and management of overweight, obesity, and their sequelae must be addressed in clinical practice in order to optimise the overall health of the haemophilia population21. Inadequate physical activity is still commonly observed in clinical practice. Insufficient education by haematologists and other involved specialists and possibly parents’ fears with consequent overprotection, especially of children, can contribute to this inadequacy. Therefore, concrete steps must be taken to encourage PwH to decrease caloric intake and increase physical activity.

-

3. Movement coordination, muscle strength and flexibility are important for improving joint function and stability, preserving bone density, and reducing the risk of bleeding.

There is some evidence that low impact physical activity may reduce bleeds and increase joint stability in PwH3–5. Different types of exercise have been shown to be beneficial on specific aspects of the motor deficits of PwH. Programmes that try to apply such different approaches together could offer the greatest benefit14. For example flexibility exercises and stretching may have great benefit by improving muscle strength and reducing muscle stiffness. In turn, improving joint function increases the range and the control of motion. Joint stability may take advantage from sensorimotor and balance training26,27. Moreover, exercise programmes are crucial to preserve bone density, which is often reduced also in young patients with severe haemophilia28. Inadequate physical activity during childhood predisposes to not reaching an adequate peak in bone mass, a condition favouring the development of osteoporosis29,30.

-

4. Regular physical activity enhances joint function and stability and can reduce the risk of acute bleeding episodes and related complications, thus overall improving the quality of life and interpersonal skills of the person with haemophilia.

In addition to what is reported above, regular physical training contributes to preventing or decreasing haemarthroses and synovitis3,31. It has been reported that factor VIII activity increases after physical exercise both in healthy subjects and in patients with bleeding disorders. In particular, high intensity physical activity was shown to increase factor VIII activity by 2.5 times in patients with mild/moderate haemophilia A32. Notably, factor VIII may also promote bone health by acting on both osteoblast and osteoclast activity33. Other reported benefits are pain reduction and improvement in QoL34. A 2016 literature review concluded that regular exercise may promote a reduction in pain perception in PwH35. A very recent study showed that progressive strength training with elastic resistance, performed by PwH twice a week for 8 weeks, not only improved muscle strength, but also reduced general pain, improved self-rated health status, and increased desire to exercise36. Exercise programmes, together with adequate prophylactic factor concentrate therapy and educational interventions, have been reported to help PwH manage their chronic pain37. Furthermore, physical activity and sports can improve not only the physical well-being of PwH, but also their QoL, which takes into account their emotional and social well-being38–40. Among non-physical benefits of exercise and sporting activities in PwH, improvement in socialisation skills and increased self-esteem have also been reported, together with strengthening of emancipation10,41.

Topic 2 – Physical activity recommendations for people with haemophilia

-

5. In people with haemophilia with a good joint condition, such as to allow them normal activity or involve only minimal limitations, motor skills should be progressively aligned with those of their healthy peers.

In Italy, efforts are being made to share a process, with all the involved stakeholders, to bring haemophilia patients closer to sporting activities in the best possible way. A future goal, for better comprehensive care, could be to issue shared recommendations to promote physical activity from an early age. Sport is essential for psycho-physical maturation of children and adolescents, including those affected by haemophilia or other chronic conditions10,42,43. On the other hand, in clinical practice, an excessive fear of exposing PwH to the risk of harm is often perceived, which actually leads to the opposite risk of precluding exercise for those who could benefit from it44. A very recent retrospective study on participation in sports, reviewing data from three consecutive annual clinic visits of Dutch PwH aged 6–18, found encouraging results, concluding that high sports participation (including high-risk sports) was associated with low injury rates45. To balance the fear of bleeding risks and potential benefits of exercise, it is essential to individualise the risk assessment and consequently the recommendations, taking into account severity of the disease, personalised prophylactic treatment, joint status, presence of comorbidities, and type of exercise/sports. The Activity-Intensity-Risk (AIR) study provides a useful framework for discussion with patients/families, identifying activities that may be modified to decrease risk in PwH, and others with non-modifiable inherent risks to be considered with great caution46. The experts agreed that physical activity programmes for PwH with a good joint condition should tend to be aligned with those performed by the patients’ healthy peers. Some studies have actually shown that PwH can be as physically active as the general population47,48.

-

6. In adults with arthropathy and the elderly, the risk of trauma/falls is increased due to structural and/or functional joint instability, resulting in an increased risk of injury, head trauma and intracranial haemorrhage. In these cases, instability should be minimised through personalised physiotherapy programmes.

Thanks to the dramatic improvements in the management of their disease and co-morbidities, PwH currently have a life-expectancy that approaches that of the general population. In ageing PwH, chronic arthropathy is the main comorbidity, leading to muscle weakness and atrophy, impaired gait and balance, and the risk of falling49. In turn, these musculoskeletal conditions increase the risk of injury, head trauma and intracranial haemorrhage. Moreover, after a fall, pain and increased fear of falling again may produce behavioural changes that could have other significant health consequences50,51. Regular exercise programmes incorporating aerobics, strength training and balance and flexibility activities have been shown to help to improve stability and functional mobility and reduce the risk of falls and fractures52,53. However, given the challenges associated with haemophilia, especially in elderly and arthropathic subjects, these patients should be referred to appropriately trained physiotherapists54.

-

7. People with haemophilia with inhibitors should also be encouraged to carry out regular physical activity, but with particular caution and timely monitoring of the effectiveness of prophylaxis for the prevention of acute bleeding events, so that physical activity is conducted safely.

The development of inhibitors continues to be the most important treatment complication in haemophilia. PwH with inhibitors report poorer health-related QoL compared with those without inhibitors, because their bleeds are more difficult to treat and result in more severe joint deterioration, with a greater impact of pain and mobility-related problems55–57. Potential serious consequences of physical activity in these patients should not, therefore, be underestimated. However, based on current evidence55, the experts agreed that also PwH with inhibitors may benefit from participation in sports and physical activity; therefore, regular exercise should not be neglected by these patients. Of course, exercise programmes should be tailored to the individual patient and gradually extended in time and frequency, patients should be monitored and assessed carefully by the multidisciplinary team, and the effectiveness of prophylaxis should be monitored closely by the haematologist.

Topic 3 – Choice and management of sporting activities in patients with haemophilia

-

8. The choice of the type of sport to be practised should derive from a shared consensus of a multidisciplinary team composed of haematologists, specialists in the management of disorders of the musculoskeletal system (orthopaedists, physiatrists, physiotherapists), and specialists in sports medicine. The last will have the task of helping people with haemophilia to choose the sporting activity that best suits their physical conditions and assessing the absence of contraindications, including those not related to haemophilia, also taking into account the wishes and expectations of the individual.

PwH are best managed by multidisciplinary teams, in order to guarantee optimal care of all aspects of the disease. It has been suggested that advice on an appropriate kind of sports should be given by a team including not only experts in coagulation disorders, but also in sports medicine, orthopaedics, physiatry and physiotherapy. These specialists have the task to assess the patient’s conditions and collectively identify the right types of sport, optimising benefits and minimising risks33,58. Counselling should take into account that each individual has a unique exercise tolerance and physical capacity, but also preferences and skills. Given the impact of physical activity and sport on the psychophysical well-being of PwH, the support of a psychologist would also be of benefit. PwH should thus receive tailored recommendations from the team about the composition and rate of increase of the training programme and should undergo regular physical examinations, possibly with imaging evaluations if needed, as well as close monitoring of prophylaxis14,43.

-

9. It is desirable that the multidisciplinary team promotes motor activity in people with haemophilia since childhood and helps the individual to identify the most appropriate type of sport, also taking into account the potential risks, in order to avoid imposing subsequent limitations, which could cause frustration or even the patient’s complete refusal to practise any form of physical activity or sport.

Children and adolescents with haemophilia on early prophylaxis may not yet have developed arthropathy and appropriate training is recommended especially for them to improve coordination, flexibility, and muscle strength, with the aim of preventing or reducing haemarthrosis, thereby possibly delaying the onset of arthropathy14. A sporting activity, whatever it is, should be encouraged from childhood or as soon as possible. The Canadian Haemophilia Society (CHS) issued a guide for families addressing recommendations and useful tips for fitness, including how to choose an activity59. Among the various criteria, many of which already discussed above, the fact that choosing a sport is a highly individualised decision is underlined. It is essential to select an activity that appeals to those who have to practise it, one that allows them to have fun and that perhaps can be shared with friends or relatives. The specific benefits and risks must be weighed for an individual patient and the chosen activity. In addition to the physical risks, the risk of authorising an activity that may later turn out to be inappropriate must also be adequately evaluated, since this can possibly generate frustration in PwH and the risk of completely precluding the continuation of the physical activity or sport. A previous bad experience is reported by the Canadian guidelines as one of the main “roadblocks” to physical activity59.

-

10. One of the tasks of the specialists of a haemophilia centre is to optimise anti-haemorrhagic prophylaxis, taking into account the risks related to the sporting practice of the individual.

Within the multidisciplinary team, the haematologist has the task of establishing personalised prophylaxis regimens (doses, intervals and timing of factor concentrate infusions) and strictly monitoring their effectiveness according to the physical activity performed by the individual person with haemophilia. Long-term prophylaxis started early has been shown not only to reduce the frequency of bleeds, thereby delaying chronic joint disease, but also to enable PwH to conduct a physically active life, even during adulthood when arthropathy is expected to impair their physical activity60.

PwH on an intermediate-dose prophylaxis regimen showed age-related declines in participation in sports, joint status, and physical functioning, at variance with those on high-dose prophylaxis61. Individualisation, monitoring and optimisation of therapy regimens, based on an individual’s bleeding pattern, musculoskeletal conditions, and level of physical activity, are essential for optimal clinical outcomes and the long-term continuation of physical activity or sport62.

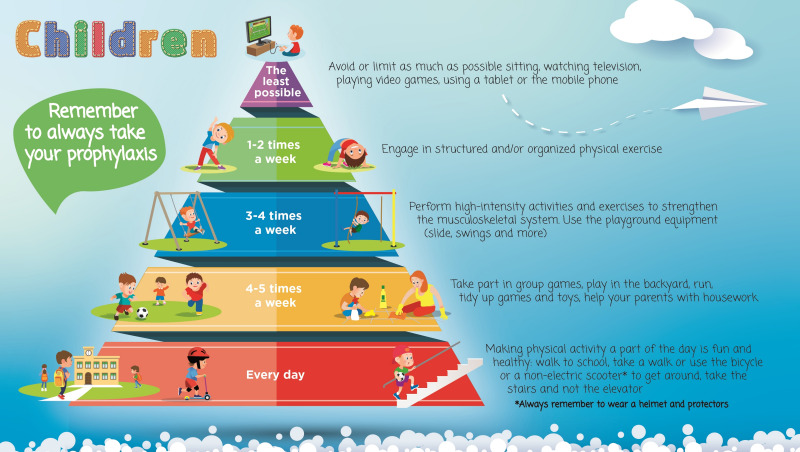

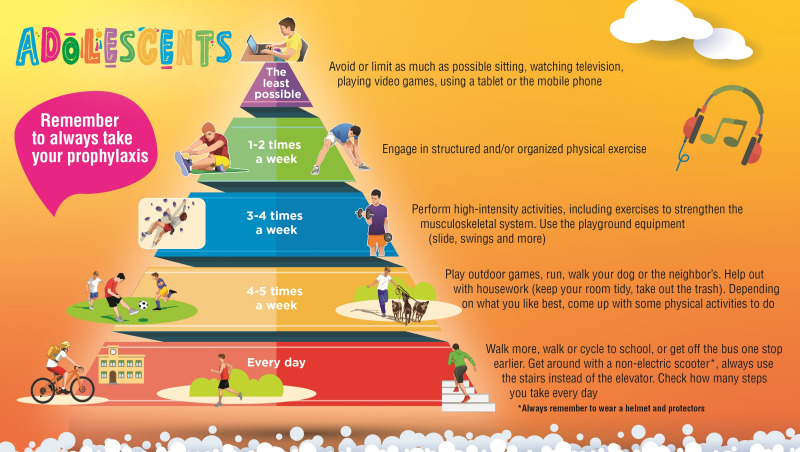

In addition to formulating the statements, the group of Italian experts also sought to create practical tools proposing different physical activities and frequencies for different age groups, which the haemophilia management team could share with patients and caregivers to encourage exercise and discuss the available options. Even though there is not a consensus on which sports should be encouraged for PwH, there is a fair amount of literature discussing the appropriate selection of a physical activity or sport9,46,58. The experts designed three pyramids, listing the advised physical activities ordered by recommended frequency, for the three different stages of life, i.e., for children, adolescents, and adults without evidence of arthropathy (Figures 1–3). A fourth pyramid, called translational, was created for all PwH who wish to practice a sport, regardless of age (Figure 4). The pyramids propose a series of activities to be carried out with decreasing frequency, from regular daily walking to structured exercise or sports activities, that can be interactively discussed between the multidisciplinary management team and the patient/caregiver to select the preferred and most suitable physical activities.

Figure 1.

The pyramids of movement for people with haemophilia. Physical activities and frequency recommended for children determined by consensus of the working group (N=40)

Figure 2.

The pyramids of movement for people with haemophilia. Physical activities and frequency recommended for adolescents determined by consensus of the working group (N=40)

Figure 3.

The pyramids of movement for people with haemophilia. Physical activities and frequency recommended for adults with no signs of arthropathy determined by consensus of the working group (N=40)

Figure 4.

The pyramids of movement for people with haemophilia (PwH). Translational pyramid determined by consensus of the working group (N=40)

CONCLUSIONS

With the limitation of a small number of final voters, due to the organizational difficulties associated with the COVID pandemic, the working group determined by consensus that physical activity can be considered a low-price intervention that can prevent/reduce the occurrence of chronic diseases which significantly increase costs for the health system63, and is confident that these simple recommendations and tools can help increase in PwH the diffusion of physical activity and sports, which have been shown to bring multiple physical and psychological benefits. To further support counselling on sports participation, future research should include prospective studies focusing on participation in sports, the exposure to specific risks that this entails and clinical outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Authors are grateful to Renata Perego, MD, for her help in drafting the manuscript, and to AICE for making their website available.

APPENDIX 1

Members of the MEMO Study Group include the following (in alphabetical order):

| Elena Balestri | Operative Unit of Trasfusional Medicine and Centre for Inherited Bleeding Disorders, “M. Bufalini” Hospital, Cesena, Italy |

| Maria Basso | Haemorrhagic and Thrombotic Diseases Service, “A. Gemelli” Fondazione Policlinico Universitario IRCCS, Rome, Italy |

| Eugenia Biguzzi | “A. Bianchi Bonomi” Haemophilia and Thrombosis Centre, IRCCS Ca’ Granda Foundation Policlinico Hospital, Milan, Italy |

| Elena Anna Boccalandro | “Angelo Bianchi Bonomi” Haemophilia and Thrombosis Centre IRCCS Foundation Maggiore Policlinico Hospital, Milan, Italy |

| Isabella Cantori | Regional Centre for Diagnosis and Treatment of Congenital Haemorrhagic Diseases and Thrombophilia, Macerata Hospital, Macerata, Italy |

| Christian Carulli | Orthopaedic Clinic, University of Florence, Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy |

| Alberto Catalano | Immunohaematology and Transfusion Medicine Service, “SS. Annunziata” Hospital, Chieti, Italy |

| Laura Contino | SSD Haemostasis and Thrombosis Centre, “SS Antonio e Biagio” Hospital, Alessandria, Italy |

| Patrizia Di Gregorio | Immunohaematology and Transfusional Medicine Service, “SS. Annunziata” Hospital, Chieti, Italy |

| Giovanni Di Minno | Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, “Federico II” University, Naples, Italy |

| Paola Ferrazzi | Centre for Thrombosis and Haemorrhagic Diseases, Humanitas-IRCCS Clinical and Research Centre, Rozzano, Milan, Italy |

| Paola Giordano | Department of Paediatrics, “Giovanni XXIII” Children’s Hospital, “Aldo Moro” University of Bari, Bari, Italy |

| Anna Chiara Giuffrida | Haemophilia Centre-Department of Transfusion Medicine, Verona University Hospital, Verona, Italy |

| Matteo Luciani | Oncohaematology Department, IRCCS “Bambino Gesù” Pediatric Hospital, Rome, Italy |

| Maria Francesca Mansueto | Department of Health Promotion, Mother and Child Care, Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties, University of Palermo Haemophilia Centre and Haematology Unit, “P. Giaccone” University Hospital, Palermo, Italy |

| Renato Marino | Haemophilia and Thrombosis Centre, “Giovanni XXIII” Policlinico, Bari, Italy |

| Marco Martinelli | “T. Camplani” Foundation-”Domus Salutis” Rehabilitation Hospital, Brescia, Italy |

| Tiziano Martini | Haemophilia and Transfusion Centre, “M. Bufalini” Hospital, Cesena, Italy |

| Emilio Valter Passeri | “T. Camplani” Foundation, “Domus Salutis” Rehabilitation Hospital, Brescia, Italy |

| Berardino Pollio | Regional Reference Centre for Inherited Bleeding and Thrombotic Disorders, Transfusion Medicine, “Regina Margherita” Children’s Hospital, Turin, Italy |

| Paola Stefania Preti | Thrombosis and Haemorrhagic Diseases Centre, “San Matteo” Hospital Foundation, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy |

| Paolo Radossi | Onco Haematology Unit, Veneto Institute of Oncology IOV-IRCCS, Padua, Italy |

| Clara Sacco | Thrombosis and Haemorrhagic Diseases Centre, Humanitas Clinical and Research Centre-IRCCS, Milan, Italy |

| Rita Carlotta Santoro | Regional Haemophilia Centre, Haemostasis and Thrombosis Unit, AOPC Pugliese-Ciaccio Hospital, Catanzaro, Italy |

| Mario Schiavoni | AICE member; Past Director, Centre for Haemophilia and Rare Bleeding Disorders, “I. Veris delli Ponti” Hospital, Scorrano, Italy |

| Michele Schiavulli | Regional Haemocoagulopathies Centre, Oncology Department, A.O.R.N. Santobono-Pausillipon, Naples, Italy |

| Gianluca Sottilotta | Haemophilia Centre, Thrombosis and Haemostasis Service. Great Metropolitan Hospital of Reggio Calabria, Italy |

| Lelia Valdrè | Department of Angiology and Blood Coagulation, IRCCS University Hospital of Bologna, Bologna, Italy |

| Maria Rosaria Villa | Haemophilia and Thrombosis Centre, Haematology, Ospedale del Mare, Naples, Italy |

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

CB acted as a paid consultant to Bayer, Novo Nordisk and Roche; and received fees as an invited speaker from CSL, Novo Nordisk and Bayer; EB acted as a paid consultant/speaker/advisor for Bayer Healthcare, CSL Behring, Kedrion, Novo-Nordisk, Pfizer, Sobi and Takeda; AC acted as a paid consultant to Bayer and Novo Nordisk and received fees as an invited speaker from Novo Nordisk, Roche and Werfen; RDC participated in scientific boards for Bayer, Takeda, SOBI, Biomarin and Roche; MND received research funding and consultancy fees from Bayer, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, Takeda, Sobi and Roche; MEM acted as a paid consultant/speaker/advisor for Bayer Healthcare, Biomarin, CSL Behring, Catalyst, Grifols, Kedrion, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sobi, Roche, LFB, Spark, Octapharma and Takeda; MN acted as a consultant for Bayer, Novo Nordisk, CSL-Behring, Kedrion, Takeda, and BioFVIIIx and received speaker fees from CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Sobi, Amgen, Takeda, Bayer and Kedrion.

GP acted as a paid speaker and/or consultant for Bayer Healthcare, Baxalta/Shire/Takeda, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sobi/Biogen and Octapharma; AR attended advisory board meetings and received personal fees as a speaker in meetings organized by Bayer, CSL Behring, Kedrion, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Baxalta/Shire/Takeda and Sobi outside the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Srivastava A, Santagostino E, Dougall A, et al. WHF guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia. (3rd edition) 2020;26(Suppl 6):1–158. doi: 10.1111/hae.14046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Runkel B, Czepa D, Hilberg T. RCT of a 6-month programmed sports therapy (PST) in patients with haemophilia - improvement of physical fitness. Haemophilia. 2016;22:765–71. doi: 10.1111/hae.12957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souza JC, Simoes HG, Campbell CSG, et al. Haemophilia and exercise. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:83–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomis M, Querol F, Gallach JE, et al. Exercise and sport in the treatment of haemophilic patients: a systematic review. Haemophilia. 2009;15:43–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy M, O’Gorman P, Monaghan A, et al. A systematic review of physical activity in people with haemophilia and its relationship with bleeding phenotype and treatment regimen. Haemophilia. 2021;27:544–62. doi: 10.1111/hae.14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Minno MN, Ambrosino P, Franchini M, et al. Arthropathy in patients with moderate haemophilia A: a systematic review of the literature. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2013;39:723–31. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1354422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Musculoskeletal complications of hemophilia. HSS J. 2010;6:37–42. doi: 10.1007/s11420-009-9140-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLaughlin P, Hurley M, Chowdary P, et al. Physiotherapy interventions for pain management in haemophilia: a systematic review. Haemophilia. 2020;26:667–84. doi: 10.1111/hae.14030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner B, Krüger S, Hilberg T, et al. The effect of resistance exercise on strength and safety outcome for people with haemophilia: a systematic review. Haemophilia. 2020;26:200–15. doi: 10.1111/hae.13938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrugia A, Gringeri A, von Mackensen S. The multiple benefits of sport in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2018;24:341–3. doi: 10.1111/hae.13496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Minno MND, Santoro C, Corcione A, et al. Pain assessment and management in Italian Haemophilia Centres. Blood Transfus. 2020;19:335–42. doi: 10.2450/2020.0085-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittmeier K, Mulder K. Enhancing lifestyle for individuals with haemophilia through physical activity and exercise: the role of physiotherapy. Haemophilia. 2007;13(Suppl 2):31–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030. 2018. [Accessed on 23/03/2021]. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 14.Wagner B, Seuser A, Krüger S, et al. Establishing an online physical exercise program for people with hemophilia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2019;131:558–66. doi: 10.1007/s00508-019-01548-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goto M, Takedani H, Yokota K, Haga N. Strategies to encourage physical activity in patients with hemophilia to improve quality of life. J Blood Med. 2016;7:85–98. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S84848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health-services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Wood TJ, et al. The use of the Delphi and other consensus group methods in medical education research: a review. Acad Med. 2017;92:1491–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helms C, Gardner A, McInnes E. The use of advanced web-based survey design in Delphi research. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73:3168–77. doi: 10.1111/jan.13381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasta G, Annunziata S, Polizzi A, et al. The progression of hemophilic arthropathy: the role of biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7292. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calcaterra I, Iannuzzo G, Dell’Aquila F, Di Minno MND. Pathophysiological role of synovitis in hemophilic arthropathy development: a two-hit hypothesis. Front Physiol. 2020;11:541. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong TE, Majumdar S, Adams E, et al. Healthy Weight Working Group. Overweight and obesity in hemophilia: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(6 Suppl 4):S369–75. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilding J, Zourikian N, Di Minno M, et al. Obesity in the global haemophilia population: prevalence, implications and expert opinions for weight management. Obes Rev. 2018;19:1569–84. doi: 10.1111/obr.12746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olivieri M, Königs C, Heller C, et al. Prevalence of obesity in young patients with severe haemophilia and its potential impact on factor VIII consumption in Germany. Hamostaseologie. 2019;39:355–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1677874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang M, Peltier S, Baumann K, et al. Awareness, Care and Treatment In Obesity maNagement to inform Haemophilia Obesity Patient Empowerment (ACTION-TO-HOPE): results of a survey of US haemophilia treatment centre professionals. Haemophilia. 2020;26(Suppl 1):20–30. doi: 10.1111/hae.13919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahan S, Cuker A, Kushner RF, et al. Prevalence and impact of obesity in people with haemophilia: review of literature and expert discussion around implementing weight management guidelines. Haemophilia. 2017;23:812–20. doi: 10.1111/hae.13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blamey G, Forsyth A, Zourikian N, et al. Comprehensive elements of a physiotherapy exercise programme in haemophilia - a global perspective. Haemophilia. 2010;16:136–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De la Corte-Rodriguez H, Rodriguez-Merchan CE, Rodriguez-Merchan EC. The role of physical medicine and rehabilitation in haemophiliac patients. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24:1–9. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32835a72f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnes C, Wong P, Egan B, et al. Reduced bone density among children with severe hemophilia. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e177–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.e177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giordano P, Brunetti G, Lassandro G, et al. High serum sclerostin levels in children with haemophilia A. Br J Haematol. 2016;172(2):293–5. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faienza MF, Lassandro G, Chiarito M, et al. How physical activity across the lifespan can reduce the impact of bone ageing: a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1862. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17061862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tiktinsky R, Falk B, Heim M, Martinovitz U. The effect of resistance training on the frequency of bleeding in haemophilia patients: a pilot study. Haemophilia. 2002;8:22–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2002.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Groen WG, den Uijl IE, van der Net J, et al. Protected by nature? Effects of strenuous physical exercise on FVIII activity in moderate and mild haemophilia A patients: a pilot study. Haemophilia. 2013;19:519–23. doi: 10.1111/hae.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Valentino LA. Increased bone resorption in hemophilia. Blood Rev. 2019;33:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auerswald G, Dolan G, Duffy A, et al. Pain and pain management in haemophilia. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2016;27(8):845–54. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schäfer GS, Valderramas S, Gomes AR, et al. Physical exercise, pain and musculoskeletal function in patients with haemophilia: a systematic review. Haemophilia. 2016;22(3):e119–29. doi: 10.1111/hae.12909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calatayud J, Pérez-Alenda S, Carrasco JJ, et al. Safety and effectiveness of progressive moderate-to-vigorous intensity elastic resistance training on physical function and pain in people with hemophilia. Phys Ther. 2020;100:1632–44. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzaa106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visweshwar N, Zhang Y, Joseph H, et al. Chronic pain in patients with hemophilia: is it preventable? Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2020;31:346–52. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Von Mackensen S. Quality of life and sports activities in patients with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2007;13(Suppl 2):38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Runkel B, Von Mackensen S, Hilberg T. RCT - subjective physical performance and quality of life after a 6-month programmed sports therapy (PST) in patients with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2017;23:144–51. doi: 10.1111/hae.13079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salim M, Brodin E, Spaals-Abrahamsson Y, et al. The effect of Nordic Walking on joint status, quality of life, physical ability, exercise capacity and pain in adult persons with haemophilia. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2016;27:467–72. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howell C, Scott K, Patel DR. Sports participation recommendations for patients with bleeding disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:174–80. doi: 10.21037/tp.2017.04.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Brussel M, van der Net J, Hulzebos E, et al. The Utrecht approach to exercise in chronic childhood conditions. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2011;23:2–14. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e318208cb22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Philpott JF, Houghton K, Luke A. Physical activity recommendations for children with specific chronic health conditions: juvenile idiopathic arthritis, hemophilia, asthma, and cystic fibrosis. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20:167–72. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181d2eddd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lassandro G, Pastore C, Amoruso A, et al. Sport and hemophilia in Italy: an obstacle course. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2018;17:230–1. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Versloot O, Timmer MA, de Kleijn P, et al. Sports participation and sports injuries in Dutch boys with haemophilia. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2020;30:1256–64. doi: 10.1111/sms.13666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hernandez G, Baumann K, Knight S, et al. Ranges and drivers of risk associated with sports and recreational activities in people with haemophilia: results of the Activity-Intensity-Risk Consensus Survey of US physical therapists. Haemophilia. 2018;24(Suppl 7):5–26. doi: 10.1111/hae.13623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Groen WG, Takken T, Van Der Net J, et al. Habitual physical activity in Dutch children and adolescents with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2011;17:906–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heijnen L, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Roosendaal G. Participation in sports by Dutch persons with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2000;6:537–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2000.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stephensen D, Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Orthopaedic co-morbidities in the elderly haemophilia population: a review. Haemophilia. 2013;19:166–73. doi: 10.1111/hae.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Street A, Hill K, Sussex B, et al. Haemophilia and ageing. Haemophilia. 2006;12(Suppl 3):8–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flaherty LM, Schoeppe J, Kruse-Jarres R, Konkle BA. Balance, falls, and exercise: beliefs and experiences in people with hemophilia: a qualitative study. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2017;2:147–54. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forsyth AL, Quon DV, Konkle BA. Role of exercise and physical activity on haemophilic arthropathy, fall prevention and osteoporosis. Haemophilia. 2011;17:e870–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sherrington C, Tiedemann A, Fairhall N, et al. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated meta-analysis and best practice recommendations. N S W Public Health Bull. 2011;22:78–83. doi: 10.1071/NB10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boccalandro E, Mancuso ME, Santagostino E, et al. Successful aging with haemophilia: amultidisciplinary program. Haemophilia. 2018;24:57–62. doi: 10.1111/hae.13308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.duTreil S. Physical and psychosocial challenges in adult hemophilia patients with inhibitors. J Blood Med. 2014;5:115–22. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S63265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lindvall K, von Mackensen S, Elmståhl S, et al. Increased burden on caregivers of having a child with haemophilia complicated by inhibitors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:706–11. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DeKoven M, Wisniewski T, Petrilla A, et al. Health-related quality of life in haemophilia patients with inhibitors and their caregivers. Haemophilia. 2013;19:287–93. doi: 10.1111/hae.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hilberg T. Programmed sports therapy (PST) in people with haemophilia (PwH) “sports therapy model for rare diseases”. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13:38. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0777-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Canadian Hemophilia Society. Passport to well-being. Empowering people with bleeding disorders to maximize their quality of life. Destination fitness. [Accessed on 29/03/2021]. Available at: https://www.hemophilia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Destination-fitness-FINAL.pdf.

- 60.Khawaji M, Astermark J, Akesson K, Berntorp E. Physical activity and joint function in adults with severe haemophilia on long-term prophylaxis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2011;22:50–5. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32834128c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Versloot O, Berntorp E, Petrini P, et al. Sports participation and physical activity in adult Dutch and Swedish patients with severe haemophilia: a comparison between intermediate- and high-dose prophylaxis. Haemophilia. 2019;25:244–51. doi: 10.1111/hae.13683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oldenburg J. Optimal treatment strategies for hemophilia: achievements and limitations of current prophylactic regimens. Blood. 2015;125:2038–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-528414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valente M, Cortesi PA, Lassandro G, et al. Health economic models in hemophilia A and utility assumptions from a clinician’s perspective. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1826–31. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]