Abstract

Background

Red blood cell (RBC) transfusion is often considered a life-saving measure in preterm neonates. However, it has been associated with detrimental effects on short-term morbidities and, recently, on brain development. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the association between RBC and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in a cohort of preterm infants.

Materials and methods

This retrospective cohort study was carried out in the period 2007–2013. Preterm infants with a gestational age (GA) ≤ 32 weeks and birthweight (BW) <1,500 g were included. Infants underwent Griffiths assessment at 24±6 months corrected age (CA) and at 5±1 years of age. We used a multivariate regression model to assess the association of RBC transfusions and long-term neurodevelopment after controlling for GA, being small for GA, major neonatal morbidities, and socio-economic status. We also evaluated the impact of early RBC administration (within the first 28 days of life) compared to those performed after the first month of life.

Results

We enrolled 644 preterm infants, among whom 54.3% were transfused during their stay in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). In infants with a longitudinal follow-up evaluation (n=360), each RBC transfusion was independently associated with a reduction in the Griffiths General Quotient (GQ) by −0.96 (p=0.002) at 24 months CA. Early RBC administration had the biggest impact, especially in children without brain lesions, where the reduction in Griffiths GQ for each additional transfusion was −2.12 (p=0.001) at 24 months CA and −1.31 (p=0.006) at 5 years of age, respectively.

Discussion

In preterm infants, RBC transfusions are associated with long-term neurodevelopmental outcome, with a cumulative effect. Early RBC administration is associated with a greater reduction in Griffiths scores. The impact of RBC transfusion on neurodevelopment is greater at 24 months CA, but persists, although to a lesser degree, at 5 years of age.

Keywords: anaemia, neurodevelopment, prematurity, NICU, erythrocytes

INTRODUCTION

Prematurity affects about one in ten newborns, and is one of the leading causes of neonatal mortality and morbidities1. Among preterm infants, 16% are born very preterm (<32 weeks of Gestational Age [GA])2, with the highest risk of developing both acute comorbidities3 and long-term neurodevelopmental disorders. Indeed, up to 15% of very preterm infants suffer from severe disabilities4, and up to 50% may present other neurodevelopmental impairments, including learning and behavioural problems5. Critically ill preterm newborns may be exposed both in utero and after birth to different insults that comprise, among others, hyperoxia, hypoxia, and ischaemic-reperfusion mechanisms. All these events are associated with inflammatory response and oxidative stress, both contributing to organ damage. The preterm brain, in particular, is vulnerable to multiple dysmaturational events, affecting both white matter and neuroaxonal structures that can determine the impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes6.

Recently, various observational studies have suggested associations between red blood cell (RBC) transfusions, increased neonatal mortality, and short-term morbidities7,8. The supposed mechanisms are related to proinflammatory cytokines released after transfusion and oxidative stress9,10. In addition, packed RBC collected from adult donors are a source of heavy metals such as lead and mercury, known to be neurotoxic11.

Although a potential detrimental effect of RBC transfusions on the neurodevelopment of very preterm newborns is biologically plausible, results from post hoc analyses of randomised trials are scarce12–14.

Our study aims at evaluating the association between RBC transfusions and neurodevelopmental outcomes in a cohort of preterm infants born at less than 33 weeks of gestational age and longitudinally assessed at 2 and 5 years of age.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This single-centre retrospective cohort study enrolled all infants with GA at birth ≤ 32 weeks and with BW <1,500 g, admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of the Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico of Milan, Italy, between January 2007 and December 2013. Eligible outborn infants were enrolled if admission to our NICU was within 6 hours of birth.

The Ethical Committee of Milano Area 2 approved the study protocol. Due to the retrospective nature of the study and the anonymisation of all data collected, the need for written informed consent was waived. All procedures were carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Exclusion criteria were: major congenital anomalies, genetic syndrome, death within the first 24 hours of life, born to HIV positive mother, in utero opioid exposure, transfer to another NICU within the first 24 hours of life. Part of this cohort has been previously evaluated for the impact of RBC transfusion on short-term morbidities7.

Data collection

For each enrolled infant, we collected data on pregnancy and perinatal period, hospitalisation and pediatric follow-up.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the population included: GA at birth, BW, gender, small for gestational age (SGA) defined as BW <10th percentile15, twins or multiple pregnancies, chorionicity, twin-to-twin transfusion, antenatal corticosteroid prophylaxis, delivery mode, Apgar score at 5 minutes of life, Clinical Risk Index for Babies (CRIB II) score16.

The following short-term morbidities were considered: haemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) requiring pharmacological or surgical treatment, sepsis (defined by positive blood culture associated with clinical signs and symptoms of infection), necrotising enterocolitis (NEC)17, major surgery, retinopathy of prematurity (ROP)18, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD)19. Brain lesions were detected by cranial ultrasound (cUS) and categorised as follows: intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) grade 1–2, IVH grade 3 or any grade with venous infarction20, post-haemorrhagic ventricular dilatation (PHVD), cerebellar haemorrhage (CBH), cystic periventricular leukomalacia (cPVL), and cerebral focal lesions (defined as any other focal grey and white matter abnormalities on cUS).

Collected data on pharmacological treatments administered during hospitalisation included: RBC transfusions, inotropes, PDA treatment, erythropoietin, analgesics, and sedatives.

As per institutional standard protocol, neonates with gestational age ≤ 32 weeks were exposed to late erythropoietin for the prevention of the anaemia of prematurity. Therapy with recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEpo) was administered at the onset of anaemia with cycles of subcutaneous injections of 250 UI/kg three times a week, for one month or until discharge, whichever came first.

Enteral iron supplementation was provided at a dose of 2 mg/kg/die in stable enterally-fed preterm infants.

For each RBC transfusion, we recorded the following data: age at transfusion, pre-transfusion haemoglobin-haematocrit, and transfused volume. RBC transfusions were administered according to our institutional guidelines in force since 2006; these remained unchanged during the study period7. All RBC units were obtained from repeat voluntary donors; collection and storage procedures have been described elsewhere7. The packed RBCs were transfused within 5 days of collection in small aliquots of 10–15 mL/kg, slowly in 4 hours without feeding interruption. Clinical data included: length of hospital stay, maternal age at childbirth, and family socio-economic status (SES), computed according to Hollingshead 4-factor index21.

During the study period, all preterm infants underwent immediate cord clamping.

Perinatal characteristics and variables related to hospital stay were collected from the electronic medical records (NeoCare®, International BioMedical, Uetendorf, Switzerland).

Neurodevelopmental assessment

During scheduled follow-up examinations at 24±6 months corrected age (CA), and at 5±1 year, preterm infants underwent neurodevelopmental assessment with the Griffiths Mental Development Scales (GMDS-R)22 and the Extended Revised (GMDS-ER)23 scale administered by trained neurodevelopmental specialists. Patient follow-up data were extracted from paper medical records stored in the Pediatric Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy. The Griffiths assessment comprises six sub-scales: locomotor, personal-social, hearing and speech, eye and hand co-ordination, performance, and practical reasoning (only at 5 years). The Griffiths scales yield to standardised quotient for each subscale (mean 100, standard deviation [SD] 16) and a composite General Quotient (GQ) (mean 100, SD 12). A standardised score within the first SD (GQ>88 and subscale quotient >84) express normal neurodevelopment, while standardised scores <1 SD reveal moderate neurodevelopmental delay, and a score <2 SD indicates a severe delay.

Study design

Infants were divided into two groups based on their transfusion requirements. The transfused group included all infants receiving at least one RBC transfusion throughout their hospital stay. The control group included all infants not transfused during hospitalisation.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean and SD (or median and range for non-normal distribution); categorical variables were summarised as absolute and relative frequencies. Transfused and non-transfused infants were compared using the Student’s τ-test for normally distributed variables, and the Mann-Witney U test for non-normal distributed variables.

Fisher’s Exact test was performed for categorical variables (univariate analysis). A multivariate linear regression model was fitted to evaluate the relationship between the number of transfusions and the Griffiths scores at 24 months and at 5 years of age, respectively, adjusting for socio-demographic and clinical covariates (GA, being small for GA, major neonatal morbidities, and SES); for the evaluation at 24 months, the age (in months) at test was included in the model. Major neonatal morbidities were expressed by a specifically developed comorbidity score24. The score, derived for each outcome of interest, included comorbidities as independent variables in a linear regression model where individual comorbidities have been weighed based on the regression coefficient. The comorbidities included in the model were: severe BPD, sepsis, ROP grade 3–4, NEC (both medical and surgical), severe brain lesions (IVH grade 3 or any grade with venous infarction, cPVL, PHVD, CBH or cerebral focal lesions), and need for major surgery. The resultant comorbidity score weightings are shown in Online Supplementary Table SI.

The multivariate regression model reports the effect of a single transfusion on the Griffiths GQ and related subscales. We considered both the overall number of transfusions performed during the stay in the NICU and, separately, only those carried out during the first 28 days of life, as these latter were considered the most dangerous for subsequent developmental outcomes.

In addition, we verified that infants with longitudinal follow-up evaluation were representative of the entire study population by comparing their baseline characteristics with those of patients lost during the follow-up period.

Calculated p-values were two-tailed; p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

During the study period, 644 preterm infants were enrolled. A neurodevelopmental assessment was available for 444 infants at 24±6 months and for 384 infants at 5±1 years of age.

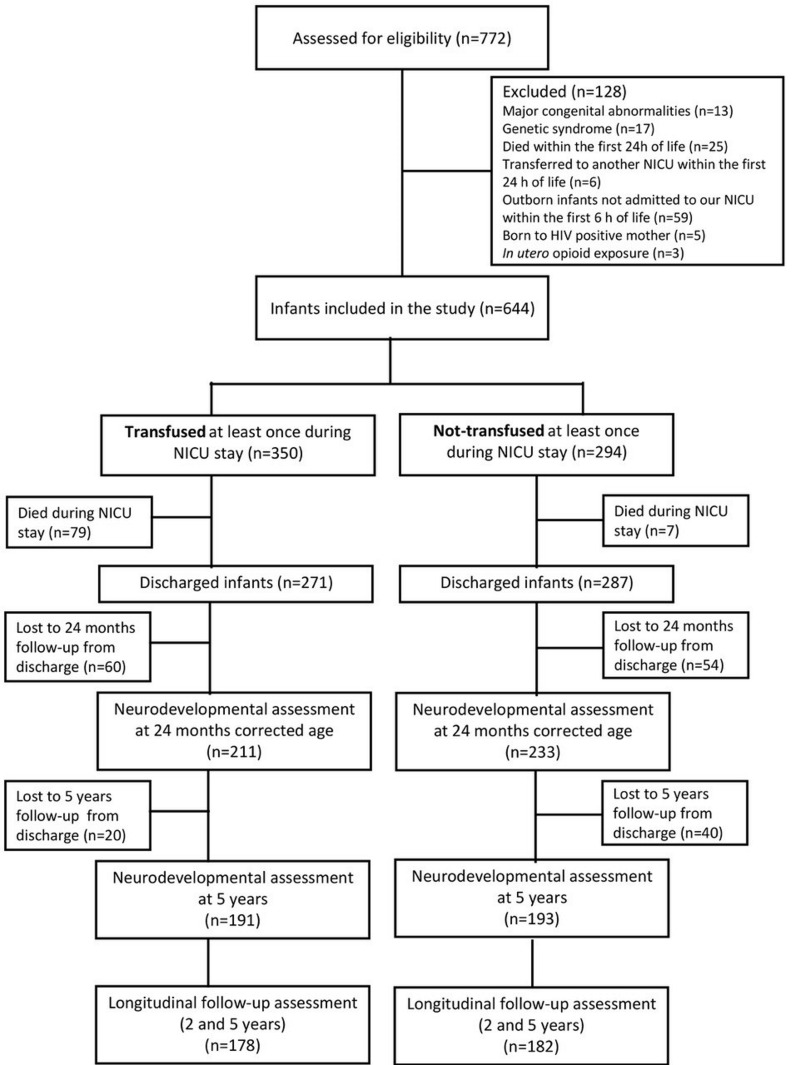

Overall, 360 infants had a complete longitudinal follow-up assessment both at 24±6 months CA and 5±1 years of age, being equally distributed between the transfused (n=178, 49.4%) and the control group (n=182; 50.6%). The flowchart of the study is reported in Figure 1. As expected, infants transfused at least once during their hospital stay, compared to the control group, had lower GA (27.3±2.1 vs 30.4±1.4 weeks; p<0.001) and BW (903.2±258.1 vs 1255.8±192.2 g; p<0.001), and showed a higher incidence of sepsis (64.6 vs 8.2%; p<0.001), severe BPD (21.3 vs 0%, p<0.0;1), severe brain lesions (14.0 vs 0.5%; p<0.001), and need for major surgery (28.7 vs 0.5%; p<0.001) during NICU stay (Table I).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study

NICU: neonatal intensive care unit; n: number.

Table I.

Characteristics of infants enrolled with longitudinal follow-up evaluation (both at 24 months corrected age and 5 years)

| Characteristics | Transfused (n=178) | Non-transfused (n=182) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Perinatal | |||

|

| |||

| Gestational age at birth (weeks), mean (SD) | 27.3 (2.1) | 30.4 (1.4) | <0.001‡ |

|

| |||

| Birth weight, mean (SD) | 903.2 (258.1) | 1,255.8 (192.2) | <0.001‡ |

|

| |||

| Male, n (%) | 84 (47.2) | 78 (42.9) | 0.458§ |

| Small for gestational age, n (%) | 53 (29.8) | 52 (28.6) | 0.817§ |

|

| |||

| Antenatal corticosteroids, n (%) | 136 (76.4) | 157 (86.3) | 0.021§ |

| Twin or multiple birth, n (%) | 79 (44.4) | 95 (52.2) | 0.142§ |

| Monocorionic, n (%) | 21 (11.8) | 25 (13.7) | 0.637§ |

| Twin-to-twin transfusion, n (%) | 15 (19.0) | 3 (3.2) | 0.001§ |

| Caesarean section, n (%) | 162 (91) | 176 (96.7) | 0.028§ |

|

| |||

| Apgar score at 5′, median (range) | 8 (2–10) | 9 (5–10) | <0.001† |

|

| |||

| CRIB II score, mean (SD) | 10.1 (3.3) | 5.4 (2.2) | <0.001‡ |

|

| |||

| Postnatal | |||

|

| |||

| Total transfusion, median (range) | 3 (1–19) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001† |

|

| |||

| Days of life at first transfusion, median (range) | 9.0 (1–56) | / | / |

|

| |||

| Pre-transfusion haematocrit (%), median (range) | 29.0 (19.0–49.2) | / | / |

|

| |||

| Transfusion ≤ 28 days of life, n (%) | 165 (92.7) | / | / |

|

| |||

| Transfusion within ≤ 28 days, median (range) | 2 (1–9) | / | / |

|

| |||

| Treated with erythropoietin, n (%) | 172 (96.6) | 164 (90.1) | 0.019§ |

|

| |||

| Inotropes, n (%) | 84 (47.2) | 11 (6.0) | <0.001§ |

|

| |||

| Analgesics, n (%) | 127 (71.3) | 37 (20.3) | <0.001§ |

| Days of invasive mechanical ventilation, median (range) | 6 (0–116) | 0 (0–11) | <0.001† |

| PDA medical treatment, n (%) | 102 (57.3) | 29 (15.9) | <0.001§ |

| PDA surgical treatmet, n (%) | 16 (9.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001§ |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 115 (64.6) | 15 (8.2) | <0.001§ |

| NEC medical, n (%) | 7 (3.9) | 2 (1.1) | <0.001§ |

| NEC surgical, n (%) | 12 (6.7) | / | |

| Major surgery, n (%) | 51 (28.7) | 1 (0.5) | <0.001§ |

| Severe ROP (grade 3–4), n (%) | 30 (16.9) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001§ |

| Severe BPD, n (%) | 38 (21.3) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001§ |

| GMH-IVH 1–2, n (%) | 42 (23.6) | 11 (6.0) | <0.001§ |

| Severe brain lesions (at least one), n (%) | 25 (14.0) | 1 (0.5) | <0.001§ |

| IVH 3–4, n (%) | 13 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| cPVL, n (%) | 4 (2.2) | 1 (0.5) | |

| PHVD, n (%) | 5 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Cerebral focal lesion, n (%) | 4 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CBH, n (%) | 6 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Median length of hospital stay, days (range) | 89.5 (28.0–376.0) | 47.0 (22.0–91.0) | <0.001† |

|

| |||

| Maternal | |||

|

| |||

| Maternal age (years), mean (SD) | 35.1 (5.4) | 35.1 (5.6) | 0.940‡ |

| Socio-economic status, mean (SD) | 37.5 (13.4) | 38.0 (14.1) | 0.775‡ |

τ-test.

Fisher’s exact test.

Mann Whitney U test.

n: number; SD: standard deviation; CRIB II: Clinical Risk Index for Babies score; PDA: patent ductus arteriosus; NEC: necrotising enterocolitis; ROP: retinopathy of prematurity; BPD: bronchopulmonary dysplasia; IVH: intraventricular haemorrhage; cPVL: cystic periventricular leukomalacia; PHVD: post-haemorrhagic ventricular dilatation; CBH: cerebellar haemorrhage.

Each patient included in the longitudinal follow-up required a median of three transfusions (range 1–19); 92.7% were transfused within the first 28 days of life.

Maternal age and SES were similar between groups.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes

At univariate analysis, non-transfused infants showed significantly higher Griffiths scores compared with those who required at least one RBC transfusion during NICU stay (Table II). After adjusting for socio-demographic and clinical variables, the multivariate regression model showed that each RBC transfusion had a statistically significant impact on the GQ scales, assessed at 24 months CA and 5 years chronological age, particularly in those without brain lesions. Specifically, in these latter patients, one RBC transfusion reduced the GQ by 1.25 points (p<0.001) at 24 months corrected age, and by 0.57 points (p=0.027) at 5 years of age (Table III).

Table II.

Neurodevelopmental outcome at 24 months corrected age and 5 years of infants enrolled with a longitudinal follow-up evaluation; p-values refer to τ-test

| Neurodevelopmental outcome | Transfused (n=178) | Non-transfused (n=182) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 24 months corrected age | |||

|

| |||

| Age at assessment (months), mean (SD) | 24.2 (1.1) | 24.1 (0.7) | 0.567 |

| General Quotient, mean (SD) | 85.8 (16.7) | 93.9 (9.0) | <0.001 |

| Locomotor, mean (SD) | 86.7 (19.0) | 96.6 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| Personal-social, mean (SD) | 80.7 (17.2) | 89.7 (11.6) | <0.001 |

| Hearing and speech, mean (SD) | 85.0 (18.0) | 92.3 (13.0) | <0.001 |

| Eye and hand co-ordination, mean (SD) | 90.8 (17.6) | 96.9 (9.3) | <0.001 |

| Performance, mean (SD) | 89.0 (17.0) | 96.0 (9.5) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| 5 years chronological age | |||

|

| |||

| Age at assessment (years), mean (SD) | 5.0 (0.3) | 4.9 (0.3) | 0.509 |

| General Quotient, mean (SD) | 85.2 (13.3) | 92.2 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Locomotor, mean (SD) | 87.8 (14.1) | 94.5 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Personal-social, mean (SD) | 85.6 (12.7) | 91.7 (6.8) | <0.001 |

| Hearing and speech, mean (SD) | 86.5 (14.2) | 92.5 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| Eye and hand co-ordination, mean (SD) | 83.6 (14.1) | 91.1 (8.0) | <0.001 |

| Performance, mean (SD) | 86.0 (12.9) | 92.3 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Practical reasoning, mean (SD) | 85.0 (13.6) | 91.3 (8.8) | <0.001 |

n: number; SD: standard deviation.

Table III.

Multivariate regression model showing the effect of one red blood cell transfusion on the neurodevelopmental outcome (Estimate) at 24 months corrected age and at 5 years of age for infants with longitudinal follow-up

| Neurodevelopmental outcome | Transfusions any time during NICU stay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 months CA | 5 years of age | |||||||

| Overall n=360 |

Without brain lesions n=342 |

Overall n=360 |

Without brain lesions n=342 |

|||||

| Estimate | p | Estimate | p | Estimate | p | Estimate | p | |

| General Quotient | −0.96 | 0.002 | −1.25 | <0.001 | −0.37 | 0.103 | −0.57 | 0.027 |

| Locomotor | −0.85 | 0.018 | −1.19 | 0.004 | −0.52 | 0.032 | −0.79 | 0.003 |

| Personal-social | −0.92 | 0.012 | −1.08 | 0.011 | −0.57 | 0.017 | −0.68 | 0.011 |

| Hearing and speech | −0.93 | 0.014 | −1.49 | 0.001 | −0.39 | 0.174 | −0.71 | 0.034 |

| Eye and hand co-ordination | −0.60 | 0.066 | −0.81 | 0.030 | −0.52 | 0.048 | −0.74 | 0.015 |

| Performance | −0.48 | 0.128 | −0.78 | 0.031 | −0.16 | 0.510 | −0.31 | 0.256 |

| Practical reasoning | −0.14 | 0.607 | −0.44 | 0.159 | ||||

| Neurodevelopmental outcome | Transfusions within the first 28 days of life | |||||||

| 24 months CA | 5 years of age | |||||||

|

Overall

n=360 |

Without brain lesions

n=342 |

Overall

n=360 |

Without brain lesions

n=342 |

|||||

| Estimate | p | Estimate | p | Estimate | p | Estimate | p | |

| General Quotient | −1.44 | 0.020 | −2.12 | 0.001 | −0.85 | 0.069 | −1.31 | 0.006 |

| Locomotor | −0.90 | 0.223 | −1.68 | 0.031 | −0.59 | 0.237 | −1.14 | 0.023 |

| Personal-social | −1.72 | 0.021 | −2.09 | 0.009 | −0.96 | 0.051 | −1.23 | 0.015 |

| Hearing and speech | −1.55 | 0.047 | −2.51 | 0.003 | −0.83 | 0.156 | −1.45 | 0.022 |

| Eye and hand co-ordination | −0.58 | 0.385 | −1.21 | 0.089 | −1.01 | 0.062 | −1.53 | 0.008 |

| Performance | −0.77 | 0.239 | −1.62 | 0.019 | −0.48 | 0.323 | −0.97 | 0.056 |

| Practical reasoning | −0.76 | 0.162 | −1.47 | 0.011 | ||||

Data are reported accounting for differences in terms of gestational age, small for gestational age, socio-economic status and comorbidities score. At 24 months, results were controlled also for age (in months) at neurodevelopmental assessment. CA: corrected age; NICU: neonatal intensive care unit; n: number.

Moreover, we observed that being transfused within the first 28 days of life had the most detrimental impact on neurodevelopment. Indeed, in infants without severe brain lesions, each RBC transfusion accounted for an average reduction of the GQ by 2.12 (p=0.001) and 1.31 points (p=0.006) at 24 months corrected age and at 5 years of age, respectively (Table III).

Overall population

There was no difference in baseline characteristics between infants included in the study for whom the 24-month evaluation was available and those lost to follow-up assessment (Online Supplementary Table SII). Patients enrolled in the study received a median of 4.5 transfusions, of which 2.7 were performed during the first month of life.

Moreover, as the population with at least one follow-up evaluation available either at 24 months (n=444) or at 5 years of age (n=384) was larger compared to that with the longitudinal follow-up, we analysed the clinical characteristics and neurodevelopmental outcomes of these infants. Neurodevelopmental outcomes and the effect of RBC transfusions were similar to those observed in the population with a longitudinal follow-up (Online Supplementary Tables SIII–SIV).

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that RBC transfusions performed in preterm infants were strongly associated with a worse neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 and 5 years of age compared with non-transfused patients. We observed that the negative effect of blood transfusions was more pronounced in patients without brain lesions and was related to the timing of administration; the first month after birth was shown to be the most sensitive period.

Extremely low gestational age newborns represent one of the most heavily transfused patient populations. Although blood transfusion is a life-saving therapy in specific cases, its primary indication is the correction of anaemia of prematurity to maintain haemoglobin concentration above a pre-defined threshold depending on the level of cardio-respiratory support required. Expected effects include improved weight gain, reduction of apnoeic events, and safeguarding vulnerable tissues and organs, in particular gut and brain, from potential damage resulting from reduced oxygen delivery25. Nevertheless, observational studies on preterm infants reported associations between RBC transfusions and increased risk of mortality and short-term neonatal morbidities10,26–28. In contrast, randomised trials aiming at evaluating the effect of different transfusion thresholds on clinical outcomes of preterm infants did not confirm these results29–31. Recently, a meta-analysis32 concluded that short-term neonatal outcomes were not affected by a lower compared to a higher transfusion threshold. However, the authors reported that many of the studies included in the analysis were at high risk of biases.

There is evidence that transfusions might be harmful in the neonatal period. Similar to reports on adult and paediatric patients, in preterm neonates, circulating proinflammatory cytokines and markers of endothelial activation increase after RBC transfusions10,33. These observations could be the expression of the so-called transfusion-related immunomodulation (TRIM)34. In the clinical setting of an underlying inflammatory condition, such as prematurity, blood transfusions may trigger immune cell activation and the proinflammatory response of the endothelial and the immune system, promoting cytokines release (the so-called two-hit hypothesis).

Moreover, after blood transfusions, non-transferrin bound iron (NTBI) increases significantly in preterm infants (but not in those born at term) and may catalyse the production of reactive hydroxyl radicals35. Indeed, a significant relationship was observed between post-transfusion NTBI and malondialdehyde, a final product of lipid peroxidation35. Finally, recent studies have demonstrated that RBC transfusions are a potential source of neurotoxic metals11. Transfused preterm newborns might be exposed to a dose of mercury and lead, exceeding the intravenous reference limits for paediatric and adult patients11. The impact of repeated co-exposure to metals that are particularly toxic during brain growth and neurodevelopment is yet to be determined.

In this context, the brain, particularly during the third trimester of gestation, is highly vulnerable to perturbations that may alter its development. Pre-oligodendrocytes (pre-OL) are the cell target of prematurity-related brain damage, being selectively vulnerable to both inflammation and oxidative stress, due to antioxidant systems’ immaturity and free iron accumulation6,9,36. This initial injury to pre-OL leads, in turn, to the impairment of myelination and, through axonal dysmaturation, of cortical and thalamic development, resulting in motor, cognitive, language, and behavioural disabilities, even in the absence of overt brain damage at conventional neuroimaging6. Based on the above observations, we hypothesised that RBC transfusion might negatively impact the long-term neurodevelopment of former preterm newborns.

We found that RBC transfusions performed in the first month after birth, independently of GA, SES, and the presence of comorbidities, reduced the GQ at two years CA by 1.44 points in patients with brain lesions and by 2.12 points in those with normal cUS. The negative effect of blood transfusions persisted, although to a lesser degree, up to 5 years chronological age.

The impact of a single transfusion on the neurodevelopmental quotients could be considered clinically negligible. However, patients required a median of 4.5 RBC transfusions during hospitalisation, mainly within the first month of life. In addition, about three-quarters of transfused patients were affected by at least one comorbidity. Thus, the cumulative effect of repeated transfusions, especially in the sickest newborns, could significantly worsen their neurodevelopment, regardless of GA and other confounders. A few previous studies with a low number of patients explored the association between neonatal transfusions and long-term neurodevelopment of former preterm newborns, but results were contradictory. The Pintos study, reporting on the follow-up assessment at 18 months corrected age of infants previously enrolled in the PINT study, concluded that maintaining higher haemoglobin in the neonatal period showed minimal advantages in the Bayley Mental Developmental Index12. Similar results came from a retrospective study on extremely low BW infants assessed at 18–24 months of corrected age13. In contrast, Von Lindern et al. did not find any clinical advantage from two different transfusion volume regimens administered during the neonatal period on the composite outcome of mortality, neuromotor developmental delay, blindness, or deafness assessed at 24 months of corrected age14.

To our knowledge, only one study has evaluated the association between blood transfusion and neurodevelopment later in childhood. Interestingly, a secondary analysis at school age of 56 preterm infants randomised at birth to a restrictive or a liberal transfusion strategy showed potential neurodevelopmental impairment to be a consequence of maintaining higher haematocrit levels in the neonatal period37. These findings were supported by advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) analysis performed at 12 years of age in 44 subjects from the same study38 showing reduced brain volume in patients enrolled in the high-transfusion threshold compared to those who were managed with the restrictive transfusion strategy.

The above studies were, however, limited by the low number of patients enrolled for secondary recruitment and failure to analyse the contribution of variables known to be associated with neurodevelopment (i.e., SES). Moreover, the use of a composite outcome that comprised mortality or brain lesions might have overestimated the impact of transfusions on neurodevelopment.

The strengths of our study include the longitudinal follow-up design of a relatively large cohort of very preterm and very low BW infants. Indeed, previous studies12–14 focused on short-term developmental or cognitive assessments that may be poor predictors of long-term outcomes. Secondly, we evaluated the impact of the SES, which affects the neurodevelopment of former preterm newborns39.

Lastly, the use of a scoring system to assign weights to comorbidities has allowed us to accurately estimate patients’ overall burden of illness, obtaining a robust estimate of transfusion effects.

This study has some limitations. First, due to the retrospective nature of our analysis, we could not draw any conclusions as to a causal relationship between RBC transfusion and impaired neurodevelopment. Moreover, as transfusions are generally prescribed to patients with more heavily compromised clinical conditions, we could not exclude the risk of bias by indication. However, the use of a regression model based on the comorbidity score to control for confounders should have limited this risk.

Only 60% of the overall population completed the longitudinal follow-up. Nevertheless, there was no difference in clinical characteristics between patients lost to follow-up and those who reached the 24-month evaluation. Moreover, GQ scale results for the whole cohort of infants available for the 2-year follow-up only were similar to those for patients enrolled in the longitudinal follow-up (Online Supplementary Content).

Finally, brain lesions were determined only by cUS, which may have underestimated the occurrence of non-cystic white matter injury that can affect subsequent neurodevelopment. However, advanced serial cUS seems highly effective in detecting preterm brain injury40, and the capability of brain MRI to predict motor development is slightly better than cUS41.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study provides evidence of a strong association between RBC transfusions and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in very preterm infants.

Two randomised trials are currently investigating the effect of different transfusion thresholds in very preterm and extremely low BW newborns on neurodevelopmental outcomes at 24 months of age42,43. While waiting for these results, it seems reasonable to adopt measures that could reduce the number of RBC transfusions, especially in the first month of life. Proven effective practices in achieving this goal include the adoption of a somewhat restrictive transfusional threshold in clinical practice, and blood sparing policies such as the use of placental blood for initial laboratory investigation, low-volume point-of-care diagnostics, and microsampling methods44. In addition, delayed cord clamping should be guaranteed whenever possible, even at the lowest gestational ages45–47. Erythropoietin administration remains controversial, although it can reduce the need for one or more transfusions in very preterm infants48.

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to Martina Vecchi, MD, for her contribution to the data collection.

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

CF and GR contributed equally as first Author to this work. SG is responsible for study concept and design, drafting the initial manuscript, and co-ordinating and supervising the investigation. CF and GR drafted the initial manuscript, carried out the investigation, and are responsible for data curation. NP carried out the statistical analyses. TB helped with the definition of the methodology and, together with VC and FMa, collected data and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. OP, MF and FMo helped with the interpretation of results and reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All Authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, et al. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health. 2013;10:S2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purisch SE, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. Epidemiology of preterm birth. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:387–91. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costeloe KL, Hennessy EM, Haider S, et al. Short term outcomes after extreme preterm birth in England: comparison of two birth cohorts in 1995 and 2006 (the EPICure studies) BMJ. 2012;345:e7976. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore T, Hennessy EM, Myles J, et al. Neurological and developmental outcome in extremely preterm children born in England in 1995 and 2006: the EPICure studies. BMJ. 2012;345:e7961. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson S, Marlow N. Early and long-term outcome of infants born extremely preterm. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102:97–102. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volpe JJ. Dysmaturation of premature brain: importance, cellular mechanisms, and potential interventions. Pediatr Neurol. 2019;95:42–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghirardello S, Dusi E, Cortinovis I, et al. Effects of red blood cell transfusions on the risk of developing complications or death: an observational study of a cohort of very low birth weight infants. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:88–95. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1584300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dos Santos AMN, Guinsburg R, De Almeida MFB, et al. Red blood cell transfusions are independently associated with intra-hospital mortality in very low birth weight preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2011;159:371–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panfoli I, Candiano G, Malova M, et al. Oxidative stress as a primary risk factor for brain damage in preterm newborns. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dani C, Poggi C, Gozzini E, et al. Red blood cell transfusions can induce proinflammatory cytokines in preterm infants. Transfusion. 2017;57:1304–10. doi: 10.1111/trf.14080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falck AJ, Medina AE, Cummins-Oman J, et al. Mercury, lead, and cadmium exposure via red blood cell transfusions in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2020;87:677–82. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0635-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whyte RK, Kirpalani H, Asztalos EV, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome of extremely low birth weight infants randomly assigned to restrictive or liberal hemoglobin thresholds for blood transfusion. Pediatrics. 2009;123:207–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang YC, Chan OW, Chiang MC, et al. Red blood cell transfusion and clinical outcomes in extremely low birth weight preterm infants. Pediatr Neonatol. 2017;58:216–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Lindern JS, Khodabux CM, Hack KEA, et al. Long-term outcome in relationship to neonatal transfusion volume in extremely premature infants: a comparative cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenton T. A new growth chart for preterm babies: Babson and Benda’s chart updated with recent data and a new format. BMC Pediatr. 2003;16:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parry G, Tucker J, Tarnow-Mordi W. CRIB II: an update of the clinical risk index for babies score. Lancet. 2003;361:1789–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13397-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg. 1978;187:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197801000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. The International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity Revisited. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:991–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.7.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. NICHD/NHLBI/ORD Workshop Summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1723–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Volpe J. Neurology of the Newborn. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollingshead A. Four factor index of social status. Yale J Sociol. 1975;8:21–52. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Battaglia F, Savoini M. [Traduzione e adattamento delle: GMDS-R Griffiths Mental Development Scales Revised 0 2 Anni)]. Florence: Giunti OS; 2007. [In Italian.] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luiz D, Faragher B, Barnard A, et al. Griffiths Mental Development Scales - Extended Revised (GMDS-ER) Ofor: ARICD; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta HB, Mehta V, Girman CJ, et al. Regression coefficient-based scoring system should be used to assign weights to the risk index. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;79:22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Lindern JS, Lopriore E. Management and prevention of neonatal anemia: current evidence and guidelines. Expert Rev Hematol. 2014;7:195–202. doi: 10.1586/17474086.2014.878225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Fang J, Su H, Chen M. Risk factors for bronchopulmonary dysplasia in neonates born at ≤ 1500 g (1999–2009) Pediatr Int. 2011;53:915–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2011.03399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghirardello S, Lonati CA, Dusi E, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis and red blood cell transfusion. J Pediatr. 2011;159:354–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howarth C, Banerjee J, Aladangady N. Red blood cell transfusion in preterm infants: current evidence and controversies. Neonatology. 2018;114:7–16. doi: 10.1159/000486584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell EF, Strauss RG, Widness JA, et al. Randomized trial of liberal versus restrictive guidelines for red blood cell transfusion in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1685–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen HL, Tseng HI, Lu CC, et al. Effect of blood transfusions on the outcome of very low body weight preterm infants under two different transfusion criteria. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:110–6. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(09)60045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirpalani H, Whyte RK, Andersen C, et al. The premature infants in need of transfusion (pint) study: A randomized, controlled trial of a restrictive (LOW) versus liberal (HIGH) transfusion threshold for extremely low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 2006;149:301–7e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keir A, Pal S, Trivella M, et al. Adverse effects of red blood cell transfusions in neonates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfusion. 2016;56:2773–80. doi: 10.1111/trf.13785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirano K, Morinobu T, Kim H, et al. Blood transfusion increases radical promoting non-transferrin bound iron in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;84:188–93. doi: 10.1136/fn.84.3.F188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keir AK, McPhee AJ, Andersen CC, Stark MJ. Plasma cytokines and markers of endothelial activation increase after packed red blood cell transfusion in the preterm infant. Pediatr Res. 2013;73:75–9. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stark MJ, Keir AK, Andersen CC. Does non-transferrin bound iron contribute to transfusion related immune-modulation in preterms? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013;98:424–9. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagberg H, Mallard C, Ferriero DM, et al. The role of inflammation in perinatal brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:192–208. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCoy TE, Conrad AL, Richman LC, et al. Neurocognitive profiles of preterm infants randomly assigned to lower or higher hematocrit thresholds for transfusion. Child Neuropsychol. 2011;17:347–67. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2010.544647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nopoulos PC, Conrad AL, Bell EF, et al. Long-term outcome of brain structure in premature infants: Effects of liberal vs restricted red blood cell transfusions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:443–50. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benavente-Fernández I, Synnes A, Grunau RE, et al. Association of socioeconomic status and brain injury with neurodevelopmental outcomes of very preterm children. JAMA Netw open. 2019;2:e192914. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plaisier A, Raets MMA, Ecury-Goossen GM, et al. Serial cranial ultrasonography or early MRI for detecting preterm brain injury? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100:F 293–F300. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards AD, Redshaw ME, Kennea N, et al. Effect of MRI on preterm infants and their families: a randomised trial with nested diagnostic and economic evaluation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018;103:F15–F21. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirpalani H, Bell E, D’Angio C, et al. Protocol: Transfusion of Prematures (TOP) Trial – Does a Liberal Red Blood Cell Transfusion Strategy Improve Neurologically-Intact Survival of Extremely-Low-Birth-Weight Infants as Compared to a Restrictive Strategy? 2012. [Accessed on 10/05/2020]. Available at: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/about/Documents/TOP_Protocol.pdf.

- 43.ETTNO Investigators. The ‘Effects of Transfusion Thresholds on Neurocognitive Outcome of extremely low birth-weight infants (ETTNO)’ study: background, aims, and study protocol. Neonatology. 2012;101:301–5. doi: 10.1159/000335030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chirico G. Red blood cell transfusion in preterm neonates: current perspectives. Int J Clin Transfus Med. 2014;2:21–8. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghirardello S, Di Tommaso M, Fiocchi S, et al. Italian recommendations for placental transfusion strategies. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:372. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Committee on Obstetric Practice AC of O and G. Committee Opinion No. 684 Delayed umbilical cord clamping after birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e5–e10. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wyllie J, Bruinenberg J, Roehr CC, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 7. Resuscitation and support of transition of babies at birth. Resuscitation. 2015;95:249–63. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aher SM, Ohlsson A. Late erythropoiesis-stimulating agents to prevent red blood cell transfusion in preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2:CD004868. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004868.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.