Abstract

This cohort study examines the association between the primary care payment model and telemedicine use for Medicare Advantage enrollees during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Patterns of outpatient care shifted dramatically during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic,1 with deferred in-person care leading to substantial revenue losses for primary care organizations.2 This shift created a strong financial incentive to move visits to telemedicine, especially among organizations reimbursed under fee-for-service payment models. Primary care organizations reimbursed under value-based payment models did not experience the same near-term financial incentives but may have found it easier to expand telemedicine access given underlying technology and infrastructure investments.3 To better understand these dynamics, we examined the association between the primary care payment model and telemedicine use for Medicare Advantage enrollees during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

For this cohort study, we identified beneficiaries continuously enrolled in Medicare Advantage health maintenance organization (HMO) plans offered by Humana, Inc, from January 1, 2019, to September 30, 2020. Enrollees in HMO plans are required to select a primary care clinician, which we used to attribute patients to a primary care organization. We then used contract data to identify the payment model under which the organization was reimbursed for the patients’ care and classified those payment models according to the following taxonomy: fee-for-service; shared savings with upside-only financial risk; shared savings with downside financial risk; or capitation, as described in the eMethods of the Supplement. We considered shared savings with downside financial risk and capitation to represent advanced value-based payment models.

Next, we identified audiovisual and audio-only telemedicine visits with the attributed primary care organization from January 1, 2020, to September 30, 2020, using paid outpatient claims, as described in the eMethods of the Supplement. We then assessed changes in weekly rates of telemedicine utilization, stratified by primary care payment model. Finally, we estimated the association between telemedicine use and primary care payment model using a patient-level negative binomial regression model that adjusted for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, Medicare eligibility criteria, comorbidity,4 and practice size, and included hospital referral region fixed effects. Race/ethnicity was assessed according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services beneficiary race code, which reflects data self-reported to the Social Security Administration.

An Advarra institutional review board deemed the study exempt and waived informed consent because it used only retrospective deidentified data and did not meet the criteria found in the Regulations for the Protection of Human Subjects (45 CFR §46). Data analyses were performed from December 30, 2020, to May 14, 2021, using SAS Enterprise Guide, version 8.2 (SAS Inc). P values were 2-tailed and statistical significance was defined as P < .05. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Results

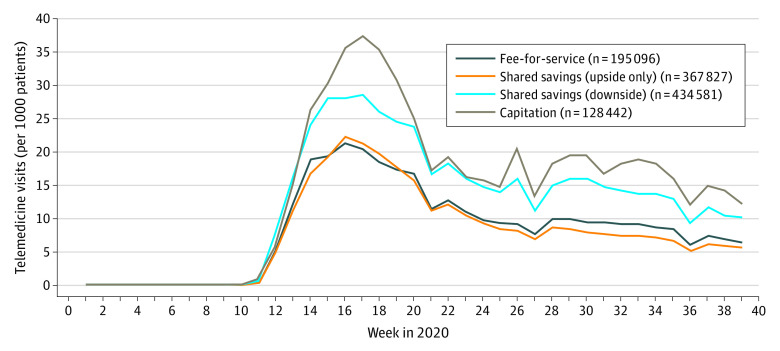

The study population of 1 125 946 patients (mean [SD] age, 74.7 [6.7] years; 645 489 [57.3%] women) comprised 28 508 (2.5%) Asian, 228 105 (20.3%) Black, 121 016 (10.8%) Hispanic, 1732 (0.2%) Native American, and 733 803 (65.2%) White individuals. Telemedicine use rose faster and reached higher absolute levels among those patients attributed to primary care organizations reimbursed via advanced value-based payment models compared with those reimbursed via fee-for-service (Figure). In multivariable analyses of cumulative telemedicine visits from March 1, 2020, to September 30, 2020, primary care payment model was significantly associated with telemedicine utilization (Table). Compared with patients attributed to organizations reimbursed under fee-for-service, the marginal effects of primary care payment model on telemedicine visits per 1000 patients were −12.9 (95% CI, −17.4 to −8.4) for shared savings with upside-only financial risk, 71.5 (95% CI, 66.9 to 76.1) for shared savings with downside financial risk, and 105.6 (95% CI, 96.1 to 115.1) for capitation.

Figure. Trends in Weekly Telemedicine Visits for Medicare Advantage Enrollees, by Primary Care Payment Model, January 1, 2020, to September 30, 2020.

Table. Association Between Patient and Primary Care Organization Characteristics and Telemedicine Visits for Medicare Advantage Enrollees During the COVID-19 Pandemic, March 1, 2020, to September 30, 2020.

| Variablea | Patients, No. (%) | Marginal effect (95% CI)b | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care payment modelc | |||

| Fee-for-service | 195 096 (17.3) | 0 [Reference] | NA |

| Shared savings (upside only) | 367 827 (32.7) | −12.9 (−17.4 to −8.4) | <.001 |

| Shared saving (downside) | 434 581 (38.6) | 71.5 (66.9 to 76.1) | <.001 |

| Capitation | 128 442 (11.4) | 105.6 (96.1 to 115.1) | <.001 |

| Age, y | |||

| 65-74 | 631 754 (56.1) | 0 [Reference] | NA |

| 75-84 | 384 625 (34.2) | −28.7 (−31.7 to −25.7) | <.001 |

| ≥85 | 109 567 (9.7) | −34.5 (−39.0 to −30.0) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 480 457 (42.7) | 0 [Reference] | NA |

| Female | 645 489 (57.3) | 61.1 (58.3 to 63.9) | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicityd | |||

| White | 733 803 (65.2) | 0 [Reference] | NA |

| Asian | 28 508 (2.5) | −8.1 (−16.2 to 0.0) | .05 |

| Black | 228 105 (20.3) | 44.8 (41.0 to 48. 6) | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 121 016 (10.8) | 38.1 (33.4 to 42.8) | <.001 |

| Native American | 1732 (0.1) | −25.9 (−58.1 to 6.3) | .13 |

| Other | 12 782 (1.1) | 43.3 (30.8 to 55.8) | <.001 |

| Dual Medicare and Medicaid eligible | 189 581 (16.8) | −5.9 (−11.4 to −0.4) | .06 |

| Medicare low-income subsidy eligible | 251 233 (22.3) | 25.9 (20.7 to 31.1) | <.001 |

| Social Security Disability eligible | 177 741 (15.8) | 31.6 (27.7 to 35.5) | <.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD)e | 2.58 (2.5) | 16.06 (13.4 to 18.6) | <.001 |

| Comorbiditiese | |||

| Hypertension | 869 765 (77.3) | 81 (77.9 to 84.1) | <.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 76 986 (6.8) | −23.5 (−28.9 to −18.1) | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 171 494 (15.2) | 52.8 (47.8 to 57.8) | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular diseases | 349 527 (31.0) | 68.2 (64.2 to 72.2) | <.001 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 145 341 (12.9) | 2.3 (−2.4 to 7.0) | .36 |

| COPD | 225 469 (20.0) | 34.5 (30.4 to 38.6) | <.001 |

| Diabetes without complications | 90 409 (8.0) | −4.6 (−10.2 to 1.0) | .12 |

| Diabetes with complications | 304 839 (27.1) | 28.6 (23.1 to 34.1) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 289 596 (25.7) | −19.1 (−24.0 to −14.2) | <.001 |

| End-stage renal disease | 38 140 (3.4) | −25.4 (−33.4 to −17.4) | <.001 |

| Liver disease, mild | 67 580 (6.0) | 17.6 (11.4 to 23.8) | <.001 |

| Liver disease, moderate/severe | 4469 (0.4) | −24.2 (−43.3 to −5.1) | .02 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 80 878 (7.2) | 40.3 (34.8 to 45.8) | <.001 |

| Cancers | 119 042 (10.6) | −5.4 (−11.9 to 1.1) | .12 |

| Metastatic carcinoma | 13 613 (1.2) | −60.7 (−76.8 to −44.6) | <.001 |

| HIV/AIDS | 1911 (0.2) | −55 (−82.0 to −28.0) | <.001 |

| Obesity | 330 949 (29.4) | 31.6 (28.5 to 34.7) | <.001 |

| Depression | 241 580 (21.5) | 69.2 (65.5 to 72.9) | <.001 |

| Anxiety | 190 318 (16.9) | 70.9 (66.8 to 75.0) | <.001 |

| Bipolar disorder | 13 403 (1.2) | 46.4 (33.6 to 59.2) | <.001 |

| Schizophrenia | 8899 (0.8) | −93.8 (−130.9 to −56.7) | <.001 |

| Dementia | 60 189 (5.4) | −3 (−9.3 to 3.3) | .35 |

| Psychoses | 8964 (0.8) | 48.3 (−11.2 to 107.8) | .09 |

| Alcohol abuse | 36 673 (3.3) | 20.4 (13.0 to 27.8) | <.001 |

| Drug abuse | 68 238 (6.1) | 74.5 (68.5 to 80.5) | <.001 |

| Practice size (No. of primary care clinicians)f | |||

| 1 | 402 700 (35.8) | 0 [Reference] | NA |

| 2-3 | 358 283 (31.8) | −1.7 (−5.0 to 1.6) | .30 |

| 4-7 | 238 361 (21.2) | −4.1 (−7.9 to −0.3) | .03 |

| ≥8 | 126 602 (11.2) | 15.3 (10.1 to 20.5) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NA, not applicable.

Model also included Dartmouth Hospital Referral Region fixed effects.

Reflect marginal effect on telemedicine visits per 1000 patients as compared with reference group (for categorical variables) or with 1 unit change in variable (for continuous variables).

Detail on payment model taxonomy and definitions can be found in the eMethods in the Supplement.

Race was assessed according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services beneficiary race code, which reflects data self-reported to the Social Security Administration.

Calculated using 2019 claims data.

Number of primary care clinicians in the attributed primary care organization.

Discussion

In this cohort study of Medicare Advantage enrollees during the COVID-19 pandemic, we found that the primary care payment model was significantly associated with telemedicine use. The patients attributed to the primary care organizations reimbursed under advanced value-based payment models used telemedicine services at the highest rates. Rates of telemedicine utilization were lower among patients attributed to organizations reimbursed under fee-for-service, despite those organizations facing the strongest near-term financial incentive to increase telemedicine utilization.2 This suggests that accountability for cost, quality, and disease management under value-based payment models—and the infrastructure, technology, and management systems of organizations engaging in these models—may have been a stronger catalyst for telemedicine adoption than recouping revenue from deferred in-person visits.

A limitation of this study was the inability to observe practice characteristics beyond payment model and size that may be associated with telemedicine adoption. Further research is needed to better understand the specific drivers of telemedicine adoption within physician organizations, especially as payers and policy makers consider approaches to ensure adequate, equitable, and sustainable access to telemedicine in the postpandemic era.

eMethods

References

- 1.Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Uscher-Pines L, Ganguli I, Barnett ML. Trends in outpatient care delivery and telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(3):388-391. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basu S, Phillips RS, Phillips R, Peterson LE, Landon BE. Primary care practice finances in the United States amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(9):1605-1614. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Family Physicians . Value-based payment study. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://valuebasedcare.humana.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/2017-Value-Based-Payment-Study-External.pdf

- 4.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods