Abstract

Bilophila wadsworthia is a common inhabitant of the human colon and has been associated with appendicitis and other local sites of inflammation in humans. Challenge-exposure or prevalence studies in laboratory and other animals have not been reported. B. wadsworthia is closely related phylogenetically to Desulfovibrio sp. and Lawsonia intracellularis, which are considered colon pathogens. We developed a PCR specific for B. wadsworthia DNA. Samples of bacterial DNA extracted from the feces of pigs on six farms in Australia and four farms in Venezuela were examined. Specific DNA of B. wadsworthia was detected in the feces of 58 of 161 Australian and 2 of 45 Venezuelan pigs, results comprising 100% of the neonatal pigs, 15% of the weaned grower pigs, and 27% of the adult sows tested. Single-stranded conformational polymorphism analysis of PCR product DNA derived from pigs or from known human strains showed an identical pattern. Histologic examination of the intestines of weaned B. wadsworthia-positive pigs found no or minor specific lesions in the small and large intestines, respectively. B. wadsworthia is apparently a common infection in neonatal pigs, but its prevalence decreases after weaning. The possible role of B. wadsworthia as an infection in animals and in human colons requires further study.

Bilophila wadsworthia is a slow-growing, asaccharolytic, and obligately anaerobic bacillus, making it somewhat difficult for routine culture and identification (1, 2). It has been cultured from the colon or feces of 50 to 60% of healthy adult humans, but generally in low numbers (ca. 103 to 106 CFU/g [wet weight]) (1, 2). It has been strongly associated with pathogenic infections of intra-abdominal sites, such as appendicitis and cholecystitis (4), as well as extra-intestinal sites, such as otitis (10, 23). However, challenge-exposure studies in laboratory animals have not been reported. Endotoxic and procoagulant activities have been identified in B. wadsworthia (15), and an in vitro study suggested that it may be able to attach to epithelial cells of the colon (8). Separate subgroups or strains of B. wadsworthia have been indicated by DNA fingerprinting studies (9). The possible isolation of B. wadsworthia from healthy or diseased nonhuman hosts has not previously been reported. Molecular studies, such as the identification of possible invasion or attachment genes or receptors, have not been reported.

Pigs are widely used as an animal model in comparative dietary and other biomedical studies. Healthy weaned pigs have a typical complex bacterial flora in their colon, including a remarkable variety of anaerobes (18, 19, 20). Pigs with enteric diseases can develop alterations in this flora, with elevations of primary enteropathogens, such as Brachyspira hyodysenteriae or Lawsonia intracellularis, followed by elevations in the levels of other bacteria of non or doubtful pathogenicity, such as Acetivibrio ethanolgignens or Campylobacter mucosalis, respectively (12, 19). The mere association of an organism with enteric disease is therefore not proof of its pathogenicity. B. wadsworthia is a member of the Desulfovibrionaceae and is closely related (>90% 16S ribosomal DNA [rDNA] sequence homology) to both Desulfovibrio sp. and L. intracellularis. The latter organism has been isolated from the intestines of a wide variety of host species, particularly pigs, rabbits, and hamsters (6, 13) and has recently been identified in rhesus macaque monkeys (10). It causes marked proliferation of immature epithelial cells in the intestinal epithelium in the colon or small intestine of infected animals (6, 14).

The aims of this study were to establish the prevalence of B. wadsworthia infection in healthy pigs in various age groups and to compare these organisms to human isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pig feces samples.

Feces were collected from pigs in six convenience-selected farms in Australia and four such farms in Venezuela (Table 1). The diet and housing of the pigs in both countries were similar; pigs were fed commercial meal diets of cereal base with added soybeans and vitamins. The farms were commercial enterprises using standard husbandry practices. The numbers of samples per age group are given in Table 1. The clinical features of all B. wadsworthia-infected and noninfected pigs (such as weight gain, food conversion ratios, and diarrhea) were noted.

TABLE 1.

Identification of B. wadworthia DNA in pig feces

| Farm | Locationa | No. of PCR-positive pigs/ no. of pigs testedb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suckling pigs | Grower pigs | Breeder pigs | ||

| 1 | SA | NT | 3/25 | NT |

| 2 | SA | NT | 2/16 | NT |

| 3 | SA | 10/10 | 3/10 | 0/10 |

| 4 | Vic | NT | 3/30 | NT |

| 5 | NSW | 10/10 | 1/10 | 0/10 |

| 6 | NSW | 10/10 | 8/10 | 8/10 |

| 7 to 10 | Venezuela | NT | 2/45 | NT |

| Total (%) | 30/30 (100) | 22/146 (15) | 8/30 (27) | |

SA, South Australia; Vic, Victoria; NSW, New South Wales (Australia).

Values are expressed as the number of PCR-positive pigs/the number of feces tested in that age group on each farm. NT, not tested. Suckling, grower, and breeder pigs were 2 to 3 weeks old, 4 to 10 weeks old, and 5 to 18 months old, respectively.

B. wadworthia DNA identification.

DNA was extracted from feces by addition of 0.2 g of each sample into a commercial silica matrix kit, incorporating heating (56°C, 30 min), boiling (100°C, 8 min), and centrifugation steps (Instagene; Bio-Rad). The presence of bacterial DNA in each sample was confirmed by the incorporation of final elute into eubacterial specific PCR detection assays (primers p11E and p13B). Specific primers for B. wadsworthia were designed by processing of the 16S rDNA sequence for the type strain (ATCC 49260, GenBank accession no. L35148) through PRIMER software accessed from the Human Genome Mapping Project (HGMP), Cambridge, United Kingdom. The selected nested primers were the sense outer primer 5′-GAATATTGCGCAATGGGC-3′ and the antisense outer primer 5′-TCTCCGGTACTCAAGCGTG-3′, followed by sense inner primer 5′-CGTGTGAATAATGCGAGGG-3′ and the antisense outer primer, giving a projected PCR product of 207 bp. The specificity of the design was confirmed by processing of the primer sequences through FIND PATTERN software, also accessed from the HGMP. This compared the DNA homology of these B. wadsworthia primer sequences to those of all other DNA sequences contained in the EMBO databases, also accessed via the HGMP. PCR reactions incorporating DNA samples from cultured strains of B. wadsworthia (ATCC 49260 and ATCC 51580) and related and unrelated bacteria were performed to confirm the PCR specificity. Laboratory strains of the following bacteria were used: Desulfovibrio desulfuricans; L. intracellularis; Streptococcus viridans, S. salivarius, S. zooepidemicus, S. dysgalactiae, and S. faecalis; Staphylococcus aureus; Shigella flexneri; Escherichia coli; Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. casei, and L. salivarius; Listeria monocytogenes; Bacteroides vulgatus; Bifidobacterium bifidum and B. longum; and Campylobacter jejuni. The conditions of the PCR reactions were 1 cycle of 94°C for 4 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by 28 cycles at the same temperatures but with 1 min per step, with a final extension step of 72°C for 4 min. The final reaction mixture (50 μl, total volume) for each reaction contained 200 mM concentrations of the nucleoside triphosphates, 1 U of Taq polymerase, 100 nmol of each primer, 3% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 5 μl of the final elute DNA preparation.

B. wadsworthia PCR products obtained from samples of porcine and human origin were compared by single-stranded conformational polymorphism (SSCP) analysis, as described previously (16). Briefly, 10 μl of PCR product solution was denatured in 0.3 M NaOH–1 mM EDTA by heating at 95°C for 5 min; cooled; mixed with 5× loading buffer containing xylene cyanol, bromophenol blue, and 98% formamide; and then electrophoresed through a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.6× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer for 16 h at 20°C. The voltage used was 4 W. Routine silver stains stained the entire gel, and the DNA patterns were assessed visually. Control PCR products from cultured B. wadsworthia DNA and unrelated DNA were incorporated into each gel.

Examination of infected pig colons.

Necropsies were performed on three weaned pigs (obtained from farm 4) with B. wadsworthia DNA identified in their feces by PCR. Necropsy included gross and histologic examination of portions of the small intestine (jejunum and ileum) and large intestine (cecum, proximal colon, and mid spiral colon) by routine methods (12). Control pigs with no detectable B. wadsworthia DNA identified in their feces from the same and 10 other farms were processed similarly.

RESULTS

B. wadworthia DNA identification.

Eubacterial DNA was identified in DNA extractions from each fecal specimen in this study. The identification of B. wadsworthia DNA in the feces of pigs is given in Table 1. No specific clinical signs were noted in infected pigs.

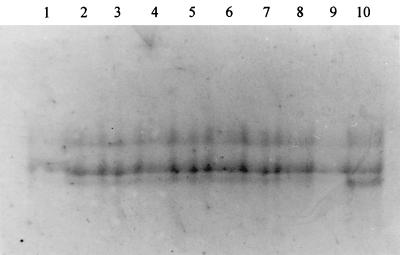

The SSCP reactions of the PCR products of B. wadsworthia DNA from pigs and control bacteria of human origin are shown in Fig. 1. PCR products from DNA extracted from pig feces showed an SSCP pattern similar to those of the human control bacterium, thus indicating species identity.

FIG. 1.

SSCP reactions of nested-PCR products from B. wadsworthia DNA from human and porcine sources. SSCP patterns from pigs 3, 15, and 25 from farm 1 (lanes 1 to 3), pigs 1 and 13 from farm 2 (lanes 4 to 5), suckling pigs 1 and 3 from farm 6 (lanes 6 to 7), grower pig 7 and breeder pig 5 from farm 6 (lanes 8 to 9), and a human cultured strain of B. wadsworthia (ATCC 51580) (lane 10).

Examination of infected pig colons.

The colon and other intestinal tissues of uninfected pigs were within normal morphologic limits. The colonic mucosa of the three infected pigs from farm 4 had mild colitis. These lesions were restricted to the proximal colon, with mild infiltration of the mononuclear cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes around several (ca. 10%) crypts. No affected crypts were detected elsewhere in the small or large intestine. The numbers of mucosal mononuclear cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes were within normal limits in the wider lamina propria of the affected and other colons. The other portions of intestine of these pigs were within normal morphologic limits.

DISCUSSION

We have established, by DNA detection techniques, that B. wadsworthia is harbored in the pig. This is the first record of this organism in nonhuman sources. It is apparently a common infection in neonatal pigs, being detected in 30 piglets tested from three farms. The source of this infection is likely to be the vagina, teats, or skin of the mothers of the piglets, which were contaminated with feces, but clear transmission data are lacking. The prevalence of the infection was reduced after the pigs were weaned onto solid food, with fewer adult pigs being found positive. However, we did demonstrate the organism in several Australian and in two Venezuelan pig farms, indicating that infection was not restricted to a single continent. We had no data to explain the variation in carriage between different pig farms. It is possible that variations in diet components may have been responsible. It is also possible that the cereal-based diet of weaned pigs or the milk-based diet of neonatal pigs acts to reduce or promote the carriage of B. wadsworthia, respectively, but there is no direct evidence of this. The stable microflora in adults may also act to reduce the carriage of this organism. Although the diet, gut length, and colonic flora of pigs are similar to those of humans, we have found no similar studies of the age-based prevalence of B. wadsworthia in humans and so cannot extrapolate our results further. It is also possible that humans, other animals, or environmental sources play a larger role in transmission. There is a lack of data on other sources of B. wadsworthia; it may be a common infection in many young animals.

The histologic and bacteriologic examination of positive colons did not indicate that B. wadsworthia was a primary cause of significant lesions in the pigs examined. Pigs are widely used a models of gastroenteric pathology in humans, including models of bacterial infections (11); however, the limited nature of the investigation does not allow the exclusion of B. wadsworthia as an enteric pathogen in either species. It is possible that B. wadsworthia is part of the normal bacterial flora of both species but that it may play a pathogenic role when in high numbers in an enteric site or in an abnormal site. The use of animal models involving B. wadsworthia as a secondary agent may help to resolve this pathogenesis, particularly in relation to dietary changes.

The present study further indicates that extraction of DNA from feces and its use in specific PCRs can give valuable noninvasive information on enteric organisms. The use of SSCP analysis was considered a robust and straightforward method to show identity of PCR products to control DNA material. The SSCP results indicate the validity of the PCR DNA product results in this study of fecal bacteria. Studies of other complex microbial communities, such as soil and compost, have also indicated that SSCP techniques offer clear validation of PCR product DNA for bacterial identity (17, 22). In this study, little variation was noted between the SSCP results from different strains of the one Bilophila species. This may indicate the unity of the various B. wadsworthia strains. A similar absence of variation in species SSCP results was noted in studies of certain other bacterial groups, such as methanogens and Bacillus subtilis (5, 7).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank CSIRO for providing core funding for this project and Connie Gebhart, Eduardo Kwiecien, Barry Lloyd, and Robyn Smith for their assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allison M J. Characterization of the flora of the large bowel of pigs: a status report. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 1989;23:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron E J, Curren M, Henderson G, Jousimies-Somer H, Lee K, Lechowitz K, String C A, Summanen P, Tuner K, Finegold S M. Bilophila wadsworthia isolates from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1882–1884. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1882-1884.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron E J. Bilophila wadsworthia: a unique gram-negative anaerobic rod. Anaerobe. 1997;3:83–86. doi: 10.1006/anae.1997.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard D. Bilophila wadsworthia bacteremia in a patient with gangrenous appendicitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:1023. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.6.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borin S, Daffonchio D, Sorlini C. Single strand conformation polymorphism analysis of PCR-tDNA fingerprinting to address the identification of Bacillus species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:87–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper D M, Swanson D L, Gebhart C J. Diagnosis of proliferative enteritis in frozen and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues from a hamster, horse, deer and ostrich using Lawsonia intracellularis-specific multiplex PCR assay. Vet Microbiol. 1997;54:47–62. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(96)01264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daffonchio D, DeBiase A, Rizzi A, Sorlini C. Interspecific, intraspecific and interoperonic variability in the 16S rRNA gene of methanogens revealed by length and single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;164:403–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerardo S H, Garcia M M, Wexler H M, Finegold S M. Adherence of Bilophila wadsworthia to cultured human embryonic intestinal cells. Anaerobe. 1998;4:19–27. doi: 10.1006/anae.1997.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerardo S M, Marina M, Citron D M, Claros M C, Hudspeth M K, Goldstein E J C. Bilophila wadsworthia clinical isolates compared by polymerase chain reaction fingerprinting. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25(Suppl. 2):S291–S294. doi: 10.1086/516229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein E C, Gebhart C J, Duhamel G E. Fatal outbreaks of proliferative enteritis caused by Lawsonia intracellularis in young colony-raised rhesus macaques. J Med Primatol. 1999;28:11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1999.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krakowka S, Eaton K A, Rings D M, Argenzio R A. Production of gastroesophageal erosions and ulcers (GEU) in gnotobiotic swine monoinfected with fermentative commensal bacteria and fed high-carbohydrate diet. Vet Pathol. 1998;35:274–282. doi: 10.1177/030098589803500406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McOrist S, Neef N. Large intestine. In: Sims L D, Glastonbury J R W, editors. Pathology of the pig. Melbourne, Australia: Pig Research and Development Council; 1997. pp. 80–100. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McOrist S, Gebhart C J, Boid R, Barns S M. Characterization of Lawsonia intracellularis gen.nov, sp. nov, the obligately intracellular bacterium of porcine proliferative enteropathy. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:820–825. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McOrist S, Gebhart C J. Porcine proliferative enteropathies. In: Straw B E, D'Allaire S, Mengeling W L, Taylor D J, editors. Diseases of swine. 8th ed. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press; 1999. pp. 521–534. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosca M, D'Alagni M, Del Prete R, Demichele G P, Summanen P H, Finegold S M, Miragliotta G. Preliminary evidence of endotoxin activity of Bilophila wadsworthia. Anaerobe. 1995;1:21–24. doi: 10.1016/s1075-9964(95)80379-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orita M, Iwahana H, Kanazawa H, Hayashi K, Sekiya T. Detection of polymorphisms of human DNA by gel electrophoresis as single-strand conformation polymorphisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2766–2770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters S, Koschinsky S, Schweiger F, Tebbe C C. Succession of microbial communities during hot composting as detected by PCR-single-strand-conformation polymorphism-based genetic profiles of small-subunit rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:930–936. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.3.930-936.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson I M, Allison M J, Bucklin J A. Characterization of the cecal bacteria of normal pigs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41:950–959. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.4.950-955.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson I M, Whipp S C, Bucklin J A, Allison M J. Bacteria from the colons of normal and dysenteric pigs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:964–969. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.5.964-969.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salanitro J P, Balke I G, Muirhead P A. Isolation and identification of fecal bacteria from adult swine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;33:79–84. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.1.79-84.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schumacher U, Bucheler M. First isolation of Bilophila wadsworthia in otitis externa. HNO. 1997;45:567–569. doi: 10.1007/s001060050133. . (In German.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwieger F, Tebbe C C. A new approach to utilize PCR-single-strand-conformation polymorphism for 16S rRNA gene-based microbial community analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4870–4876. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4870-4876.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Summanen P H, Jousimies-Somer H, Manley S, Bruckner D, Marina M, Goldstein E J C, Finegold S M. Bilophila wadsworthia isolates from clinical specimens. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(Suppl. 2):S279–S282. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.supplement_2.s210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]