Abstract

Recent scientific advances have presented substantial evidence that there is a multifaceted relationship between the microbiome and cancer. Humans are hosts to multifarious microbial communities, and these resident microbes contribute to both health and disease. Circulating toxic metabolites from these resident microbes may contribute to the development and progression of cancer. The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate microbiome and microbial shift contribution to the development and progression of cancer. This systematic review provides an analytical presentation of the evidence linking various parts of the microbiota to cancer. Searches were performed in databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, EBSCO, E-Journals and Science Direct from the time of their establishment until May 2018 with the following search terms: cancer or human microbe or cancer and human microbiome AND shift in microbes in cancer. The merged data were assessed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Cochrane’s Risk of Bias Tool was used to assess the bias. Initially, 2,691 articles were identified, out of which 60 full-text articles were screened and re-evaluated. Among them, 14 were excluded based on inclusion/exclusion criteria; eventually, 46 articles were included in the systematic review. The reports of 46 articles revealed that microbial shift involving Candida species, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Helicobacter pylori and Human papilloma virus (HPV) 16 & 18 were most commonly involved in various human cancers. In particular, organisms, such as Candida albicans, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis and HPV-16 were found to be more prevalent in oral cancer. The present systematic review emphasizes that the role and diverse contributions of the microbiome in carcinogenesis will provide opportunities for the development of effective diagnostic and preventive methods.

Keywords: Carcinogenesis, human microbiome, mouth neoplasms, oral cancer, Candida albicans

Introduction

The human microbiome is the collective genome of all bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa that survive in and on the body surfaces. There are nearly 30 trillion bacteria, and the number of microbial genes present in the human body is at least 100 times higher than the number of human genes. Based on factors such as environment, diet, lifestyle, antibiotic exposure and the immune system, the makeup of this microbial community varies between individuals. Any disturbance or alteration in these commensal organisms can have a negative impact on health and may lead to the development and progression of diseases such as cancer. The reason for this link is the immune system. The immune system not only controls microbial interaction with cancer therapies but also regulates the microbiome, which influences the development and progression of cancer. It is estimated that 20% of all fatal cancers in humans are caused by microorganisms (1,2).

Different groups of bacteria in or on the human body have been proposed to induce carcinogenesis either by interference with signaling pathways and the cell cycle or through induction of chronic inflammation. Cancer cells differ from normal cells in that the former display rapid and uncontrolled division, high metabolic rates and cellular morphology differences. The dysregulation of the cell cycle machinery is considered the hallmark of cancer. This dysregulation includes defects in cellular programs such as differentiation, proliferation, senescence and apoptosis. The term carcinogenesis is a multistep process that requires the accumulation of multiple genetic alterations that alters the functions of proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. All human cancers usually lead to increased cell proliferation, loss of cell adherence, local tissue infiltration and metastasis (3,4).

It is also believed that the microbiome causes mutagenesis by metabolic production of potentially carcinogenic substances such as acetaldehyde, nitrosamine and nitrosodiethylamine. These changes affect the symbiosis between the microbiome and the host. This systematic review aims to identify the roles and diverse contributions of the microbiome in carcinogenesis, which will provide opportunities for the development of effective diagnostic and preventive methods.

This systematic review is aimed at identifying specific components of the microbiome that play important roles in carcinogenesis and identifying microbial shifts associated with the transition from health to cancer. The investigative techniques used to identify the microbiome will also be analyzed.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist. The key question was the following: “Do the microbiome and microbial shift contribute to the development and progression of cancer?”

Study design

A systematic review of human studies was attempted to summarize the results of published studies that used the human microbiome as an etiological factor for cancer and evaluated its role in tumor development and progression, listing specific organisms involved in carcinogenesis.

Inclusion criteria

The articles included in the study were full-length, English-language articles that focused on microorganisms involved in the origins of various human cancers.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria for selecting the articles included the following:

Articles that did not examine the microbiome as an etiological factor for cancer.

Articles other than original research, such as reviews, editorial letters, books, personal opinions and abstracts.

Studies with insufficient data.

Data sources and search strategy

Databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, EBSCO, E-Journals and Science Direct were searched using keywords such as “Cancer or human microbiome or cancer and human microbiome” AND “shift in microbes in cancer”. In addition, PubMed searches were carried out for references cited in review articles dealing with the microbiome in cancer (Table 1). Articles that were published between May 2007 to May 2018 were included. The references of the selected articles were screened again for additional relevant studies that could have gone unnoticed during the electronic search.

Table 1. Methodology employed for the review.

| Statement of the objective | Method/methodology | Resources utilized | Key words used |

|---|---|---|---|

| To analyze and critically evaluate research articles that have used microbiome as etiological factor for cancer and to check the shift of human microbiome from normal to cancer | Collection of articles followed by critical evaluation of studies using human microbiome as an etiological factor for cancer and to assess the role of microbiome that played significant role in tumor development and progression, thus listing out specific microbiome that are involved in carcinogenesis | e-journals, Scopus, PubMed, EBSCO, Google scholar, Science direct | “Cancer or human microbiome or cancer and human microbiome” AND “shift in microbes in cancer” |

Study selection

The study selection was carried out in two phases. Initially, the articles were evaluated overall. We listed the various microbes examined and how their populations changed from normal health to cancer. We also listed the specific microbes involved in each study. The second phase included evaluating the different techniques used and assessing the validation of the results mentioned in each article.

Data collection

The form used to collect overall data from individual articles included the following information: Authors, journal in which the article was published, year of publication, research focus, methodologies employed, results obtained, conclusion drawn by the authors, future scope of research in the given field.

Assessing risk of bias

The Cochrane Collaboration tool (5,6) was applied to assess the risk of bias for RCTs. Bias was evaluated as a judgment (high, low, or unclear) for individual elements from seven domains. Risk of bias was assessed for each included study from 6 aspects: (I) random sequence generation (selection bias), (II) allocation concealment (selection bias), (III) blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), (IV) incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), (V) selective reporting (reporting bias), and (VII) other bias. Risk of bias was rated by two independent researchers (LM and DA). Disagreements were discussed and if they remained unresolved, the third author (RSR) was consulted.

Synthesis of results

The results of the individual studies were then summarized, and the various microbes involved in carcinogenesis were listed. Data on the same microbes were grouped and analyzed. Individual points of interests were summarized across the selected studies.

Results

Search results

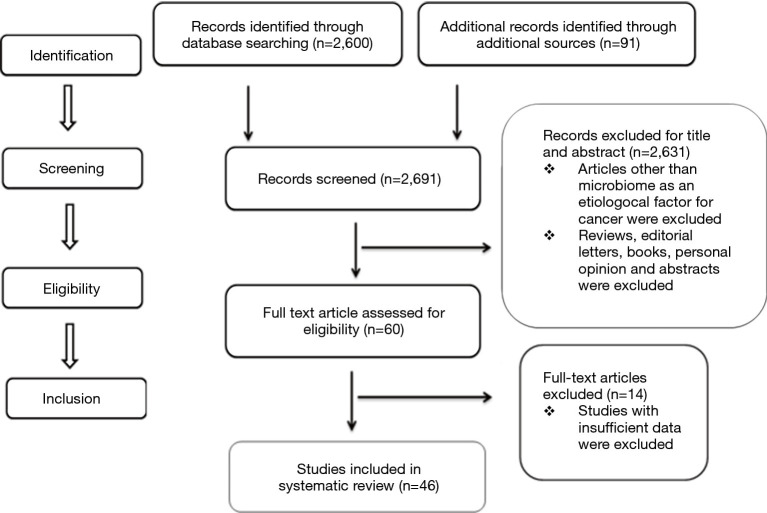

A search with the above mentioned keywords yielded a total of 2,691 results. However, these included conference presentations, letters to the editor, short communications, journal publications, books, reviews and case reports. A total of 108 potentially relevant articles were identified through screening of titles and abstracts; among those candidates, 60 full-text articles that fit the inclusion criteria were included. The selected articles were further screened by two researchers for their reliability. In case of any disagreement on the selection of a study, a third reviewer was consulted (Figure 1). A total of 46 articles were selected by the reviewers for the systematic review; these articles are listed in Table S1.

Figure 1.

Study design as per PRISMA Guidelines.

Table S1. Summary of reviewed articles.

| Author & year | Microbiome | Type of cancer | Sample | Site | Methodology & validation | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bandhary et al. [2018] | Human papilloma virus (HPV) 16 & 18 | Head & neck squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) | Tissue | Lesional site | Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) | There is no major role of HPV in carcinogenesis of head and neck SCC in coastal regions of south India |

| Almstahl et al. [2018] | Mucosal microflora | Head & neck cancer | Swab | Tongue & buccal mucosa | Culture method | There is increase in the mucosal pathogen, despite improvements in the treatment for cancer in the head and neck region |

| Ainapur et al. [2017] | Candidal species | Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) | Oral swab | Lesional site | Culture method | An increase in candidal colonization in the oral cavity of OSCC patients undergoing radiotherapy was observed |

| Naushad et al. [2017] | HPV 16 & 18, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) & mouse mammary tumor virus | Breast cancer | Tissue | Tissue blocks | PCR | The significant prevalence of viruses in breast cancer cases shows that they have a potential role in breast cancer development. The inactivation of tumor suppressor genes or activation of oncogenes by integration of HPV and MMTV viruses may lead to breast cancer development |

| Wolf et al. [2017] | Salivary microbiota | Oropharyngeal carcinoma | Swab | Saliva | 16S rRNA gene sequencing method | Changes were found in the salivary microbiome of oral and oropharyngeal SCC patients and healthy controls. These changes may be promising biomarkers for SCC tumorigenesis, disease detection and the effectiveness of potential therapeutic interventions |

| Andres-Franch et al. [2017] | Streptococcus gallolyticus | Colorectal cancer | Tissues | Colonic mucosa | Quantitative real-time PCR & DNA methylation | Colorectal cancer patients showed low prevalence of Streptococcus gallolyticus infection |

| Jain et al. [2016] | Candida species | Oral cancer | Imprint | Tongue | Imprint culture technique, validated by the sugar fermentation test, chlamydospore formation and the germ tube test | Oral cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy & chemotherapy showed an increase in candidal colonization and an alteration in the growth pattern of Candida from the carrier state to the infective state |

| Zhou et al. [2016] | Fusobacterium species, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli | Colorectal cancer | Tissue | Normal and lesional sites | Quantitative real-time PCR | Fusobacterium species and Escherichia coli were significantly increased in tumor and adjacent tissues of colorectal cancer patients compared with the tissues of healthy individuals. These findings provide evidence supporting a possible association of Fusobacterium species and Escherichia coli with transformation of colorectal mucosa from the early adenomatous polyp stages to the colorectal cancer stage |

| Berkovits et al. [2016] | Oral yeast | OSCC | Oral swab | Lesional site | Culture method, matrix-associated laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry | Oral yeast carriage was significantly elevated in OSCC patients, supporting the notion that an altered microenvironment is associated with carcinogenesis |

| Tsai et al. [2016] | Streptococcus bovis | Colorectal adenocarcinoma | Blood | Colon | Gram staining method, colonoscopy | S. bovis bacteremia was associated with colorectal adenocarcinoma, especially in female patients |

| de Sousa et al. [2016] | Candida species | Orogastric cancer | Oral swab | Lesional site | Culture method, MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry | Increased virulence was observed in yeasts isolated from orogastric cancer patients |

| Yamamura et al. [2016] | Fusobacterium nucleatum | Esophageal carcinoma | Tissue | Tissue block | Quantitative real-time PCR | The presence of Fusobacterium nucleatum in esophageal carcinoma predicts shorter survival, suggesting that it might serve as a prognostic biomarker |

| Urbaniak et al. [2016] | Microbiome | Breast cancer | Tissue | Lesional site | 16S rRNA sequencing & PCR amplification, validated by culture | The breast microbiome was observed to play important roles in both health and disease |

| Hu et al. [2015] | Oral bacteria | Gastric cancer | Tongue coating | Tongue | Tongue image analysis & gel electrophoresis | The microbiota of the tongue coating is an indicative tool for the observation and early diagnosis of gastric cancer |

| Dang et al. [2015] | HPV-16 | Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) | Saliva | Whole mouth | Real-time PCR | HPV detection in oral rinse samples may be a useful screening tool to detect HPV-associated oral cancers |

| Sharma et al. [2015] | Helicobacter pylori | OSCC | Saliva | Whole mouth | Culture method | The patients with premalignant lesions and OSCC in the present study showed a high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori |

| Hasan and AL-Jubouri [2015] | Candida species | Leukemia | Oral swab | Lesional site | Culture method, validated by germ tube formation, chlamydospore production, the urease test, and the sugar fermentation test | Oral candidiasis is a discernible complication in leukemia patients, and this study showed that the most commonly isolated species was C. guilliermondii, which represented 31.66% of cases |

| Acharya et al. [2015] | EBV | OSCC | Oral swab | Buccal cavity | PCR, validated by nested PCR | The prevalence of EBV was much higher in the OSCC cases than in the controls. One observation suggested that EBV by itself is not a risk factors for OSCC but interacts with other risk factors such as tobacco smoking and alcohol |

| Alnuaimi et al. [2015] | Candida species | Oral cancer | Saliva | Whole mouth | Quantitative real-time PCR | Oral candida colonization was significantly higher in oral cancer patients than in healthy controls. Alcohol consumption and candidal carriage could be significant risk factors |

| Mima et al. [2015] | Fusobacterium nucleatum | Colorectal carcinoma | Tissue | Tissue blocks | Quantitative real-time PCR | Fusobacterium nucleatum DNA was associated with elevated colorectal-cancer-specific mortality |

| Jahanshahi and Shirani [2015] | Candida species | OSCC | Tissue | Tissue blocks | Fluorescence staining and periodic acid–Schiff staining | Fluorescence staining is more accurate than periodic acid–Schiff staining (PAS) in identifying Candida in OSCC |

| Faghihloo et al. [2014] | EBV | Gastric cancer | Tissue | Tissue blocks | Quantitative real-time PCR | A low prevalence of EBV-associated gastric cancer was observed in Iran |

| Ghosh et al. [2014] | Viable aerobic bacteria | OSCC | Tissue | Lesional site | Histological grading, culture method | Viable aerobic bacteria were more abundant in the deeper tissues of OSCC than closer to the surface |

| Tafvizi and Fard [2014] | Cytomegalovirus | Colorectal cancer | Tissues | Tissue blocks | Nested PCR | The findings in the study were statistically significant and showed that CMV could play an important role in creating malignancy and driving the progression of cancer through the process of oncomodulation |

| Zaki et al. [2014] | Streptococcus mitis | Oral and digestive cancer | Saliva | Whole mouth | Culture & Gram staining, validated by the sugar fermentation test and the catalase test | Increase in the number of Streptococcus mitis in saliva of oral and digestive cancer patients act as an early diagnostic marker |

| Bakki et al. [2014] | Candida species | Head & neck tumors | Saliva | Whole mouth | Culture, validated by carbohydrate assimilation and fermentation tests | A high prevalence of Candida was observed in the oral cavity of patients undergoing anticancer therapy |

| Saravani et al. [2014] | EBV & human herpes virus –6 (HHV-6) | OSCC | Tissue | Tissue blocks | Real-time PCR | HHV-6 and EBV are not directly involved in OSCC |

| Xuan et al. [2014] | Methylo bacteriumradiotolerans, spingomonas yanoikuyae | Breast cancer | Tissue | Tissue blocks | 16S pyro sequencing and quantitative real-time PCR | Bacterial load might be used in conjunction with current methods to monitor the progression of breast cancer as there is an inverse correlation between bacteria load and tumor staging |

| Kafle et al. [2014] | Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) | Gastric cancer | Tissue & blood | Lesional site | Histological examination & Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) | H. pylori along with hosts genetic and dietary factors play a major role in gastric carcinogenesis in patients infected with H. pylori |

| Metgud et al. [2014] | Aerobic and facultative anaerobic | OSCC | Saliva | Mucosa, whole mouth | Culture method | Higher degree of total number of microbial colony forming unit (CFUs)/mL was found in carcinoma site and saliva |

| Cankovic et al. [2013] | Streptococcus alpha-haemoliticus | OSCC | Saliva | Lesional site | Culture method | Presence of microbial flora on the irregular oral carcinoma surface contributes to chronic inflammation |

| Weir et al. [2013] | Intestinal microbiome | Colorectal cancer | Stool | Stools samples | Pyro sequencing analysis | There are ‘‘driver bacteria’’ with pro-carcinogenic features that contribute to tumor development and ‘‘passenger bacteria’’ that may outcompete drivers to flourish in the tumor environment as the cancer progress was observed |

| Sonalika et al. [2012] | Aerobes, anaerobes, coliforms, candida and gram negative, anaerobic bacilli | OSCC | Saliva | Whole mouth | Culture method | An appropriate antimicrobial protocol at the stage of diagnosis OSCC is mandatory |

| Nola-Fuchs et al. [2012] | HPV-16 & EBV | OSCC | Oral mucosal Swab, Venous blood | Oral mucosa, cubital fossa | QIA amp Mini Elute Virus Spin kit Digene HPV genotyping RH test & VIDAS EBV kit | Role of HPV-16 & EBV is less in OSCC patients |

| Lande et al. [2012] | Mycobacterium avium complex | Lung cancer | Sputum | Lesional site | Culture method | There was an association between the presence of mycobacterium Avium Complex in respiratory, cultures of lung cancer patients and SCC located in the periphery of the lung |

| Goot-Heah et al. [2012] | HPV-18 | OSCC | Saliva | Whole mouth | Nested PCR & spectrophotometer technology | Low percentage of HPV-18 DNA was detected in OSCC, suggesting that HPV-18 may not play important role in development and progression of OSCC |

| Farrell et al. [2012] | Salivary microbiota | Pancreatic cancer | Saliva | Whole mouth | Human oral microbe identification by microarray, validation by Real-time quantitative PCR | An association between variations in salivary microbiota with pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis patients was observed. It also provides evidence that salivary microbiota may act as a non-invasive biomarker of systemic diseases |

| Dayama et al. [2011] | Helicobacter pylori | OSCC | Tissue | Cancer site | Culture method & PCR, validation-oxidase and urease test | Increased risk of oral cancer is associated with H. pylori infection |

| Saigal et al. [2011] | Candida albicans | OSCC | Saliva | Whole mouth | Culture methods, validation-chlamydospore formation, corn meal broth + 5% milk, milk serum culture | The nitrosamine compounds produced by Candidal species may be involved in which act directly or indirectly on oral mucosa |

| Ahmed and Eltoom [2010] | HPV-16 and HPV-18 | OSCC | Tissue | Tissues blocks | PCR | Association between HPV-16 and HPV-18 infection and oral cancer was observed |

| Ang et al. [2010] | HPV-16 | Oropharyngeal SCC | Tissue | Tissue blocks | In situ hybridization, validation-immunohistochemistry analysis | HPV -16 is a strong independent prognostic factor for survival among patient with oropharyngeal SCC |

| Steininger et al. [2009] | Herpes viruses | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) | Blood | Cubital fossa | Semi-quantitative ELISA and qualitative immunofluorescence assay | Among all herpes virus cytomegalo virus (CMV)-seroprevalence was significantly higher in selected CLL cohorts than in age- and gender-matched healthy adult |

| Kullander et al. [2009] | Staphylococcus aureus | SCC | Tissue and swab | Lesional and normal area | Multiple displacement amplification and PCR | A strong association between staphylococcus aureus and SCC was found which was found to be greater than HPV and SCC |

| Kang et al. [2009] | Cariogenic bacteria, periodontopathic bacteria, Candida species | Oncological patients | Saliva | Whole mouth | PCR | C.albicans was significantly more prevalent in the oncological patients than in the healthy groups |

| Saini et al. [2009] | Streptococcus viridians, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella, Candida albicans & Leptotrichia | OSCC | Saliva | Lesional site | Culture & gram staining method | Hundred percent reduction in the normal microbial flora in oral cancer was observed |

| Kurkivuori et al. [2007] | Oral Streptococci group | Oral cancer | Strains | Bacterial and clinical | Culture method, Fluorescence analysis & gas chromatography | Oral streptococci play a pivotal role in fluctuation of salivary acetaldehyde levels after alcohol consumption and increases the risk of oral cancer development |

Study results

A total of 46 articles were selected based on the reviewers’ decisions. The selected articles included original research articles in which the microbiome played an important role in carcinogenesis. Upon review of the selected articles, it was identified that oral, lung, gastric, pancreatic and colon cancers have been associated with altered microbial profiles. This shift is stimulated by changes in the microenvironment that interrupt the function of the normal microbiome and lead to alterations in the microbial composition that mediate carcinogenesis. Among the selected studies, microbes such as Candida albicans in oral cancer and Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum) in colorectal cancer displayed shifts from normal health to cancer.

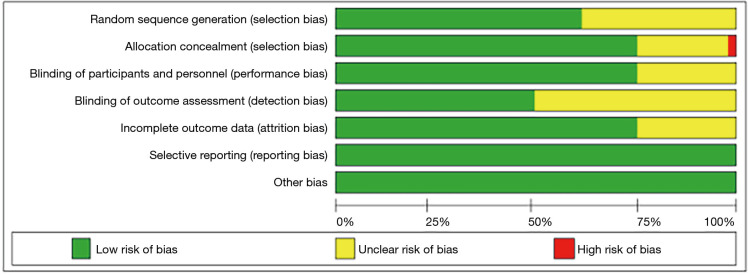

Risk of bias of the included studies

The risk of bias in the RCTs is shown in Figure 2, and the overall risk of bias for each domain is shown in Figure 2. Only 2 studies (7,8) were of high risk of bias. The Cochrane Collaboration tool was applied to assess the risk of bias for RCTs. Bias was evaluated as a judgment (high, low, or unclear) for individual elements from seven domains.

Figure 2.

Representing the overall risk of bias for each domain.

The reviewed articles are listed in Table S1, which describes the details of each study in terms of author, year, microbiome, sample, site, and methodology. A total of 22 microbes were considered as etiological factors for different cancers. The most commonly involved fungi was Candida albicans (9-21). The most commonly involved bacteria were Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) and F. nucleatum (7,22-24). Human papilloma virus (HPV) was strongly associated with various cancers (8,25-30).

Table 2 lists the microbiome and their association with cancer. In the selected studies, Candida albicans, F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis and HPV were the most common organisms involved in human cancers. Helicobacter pylori was reported to be linked to gastric cancer (31,32); F. nucleatum to colorectal cancer (22-24); Methylobacterium radiotolerans, Sphingomonas yanoikuyae, HPV, and Epstein–Barr virus to breast cancer (29,33); the Mycobacterium avium complex to lung cancer (34); and Herpesvirus and Candida species to leukemia.

Table 2. Microbiome and their association with cancer.

| Associated cancer | Microbiome involved | Literature report |

|---|---|---|

| Oral squamous cell carcinoma | Candida albicans, Streptococcus alpha hemolyticus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella, Leptotrichia, Streptococcus salivarius, Coliforms, Helicobacter pylori, Human papilloma virus - 16, 18, Epstein–Barr virus, Human herpes virus - 6, mucosal microflora | Bandhary et al. 2018, Almstahl et al. 2018, Ainapur et al. 2017, Jain et al. 2016, Berkovits et al. 2016, de Sousa et al. 2016, Acharya et al. 2015, Alnuaimi et al. 2015, Jahanshahi and Shirani 2015, Ghosh et al. 2014; Bakki et al. 2014, Saravani et al. 2014, Metgud et al. 2014, Cankovic et al. 2013, Sonalika et al. 2012, Nola-Fuchs et al. 2012, Goot-Heah et al. 2012, Dayama et al. 2011, Saigal et al. 2011, Ahmed et al. 2010, Ang et al. 2009; Kurkivuori et al. 2007 |

| Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma | Human papilloma virus - 16 & 18, Fusobacterium Nucleatum | Wolf et al. 2017, Dang et al. 2015, Ang et al. 2010 |

| Esophageal carcinoma | Salivary microbiome | Yamamura et al. 2016 |

| Breast cancer | Methylobacterium radiotolerans, Sphingomonas yanoikuyae, Human papilloma virus, Epstein–Barr virus | Naushad et al. 2017, Xuan et al. 2014 |

| Lung cancer | Mycobacterium avium complex | Lande et al. 2012 |

| Gastric cancer | Helicobacter pylori, Epstein–Barr virus, oral bacteria, Streptococcus mitis | de Sousa et al. 2016, Hu et al. 2015, Kafle et al. 2014, Zaki et al. 2014 |

| Pancreatic cancer | Salivary microbiota | Farrell et al. 2012 |

| Colorectal cancer | Intestinal microbiome, Cytomegalovirus, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Streptococcus bovis, Enterococcus Faecalis, Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides Fragilis, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus gallolyticus | Andres-Franch et al. 2017, Zhou et al. 2016, Tsai et al. 2016, Tafvizi and Fard 2014; Mima et al. 2015; Weir et al. 2013 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma of skin | Staphylococcus aureus | Kullander et al. 2009 |

| Leukemia | Herpes virus, Candida species | Hasan and AL-Jubouri 2015; Steininger et al. 2009 |

Table 3 shows the cultural characteristics of the organisms associated with carcinogenesis and lists the microbes involved in microbial shift associated with carcinogenesis. Among the selected articles, most bacteria that were identified as involved in cancer were gram-positive facultative anaerobes.

Table 3. Cultural characteristics of the organisms associated with carcinogenesis.

| Microbiome | Kingdom | Gram reactivity | Environment | Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans | Fungi | – | Aerobe or anaerobe | Sabouraud’s dextrose agar (SDA), CHROM agar culture plate |

| Streptococcus mitis | Bacteria | Gram-positive cocci | Facultative anaerobe | Streptococcus mitis agar |

| Streptococcus alpha-hemolyticus | Bacteria | Gram-positive cocci | Facultative anaerobe | Blood agar, MacConkey agar, Tiogliocolate surfaces |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Bacteria | Gram-negative bacilli | Aerobe | Aerobic media |

| Klebsiella | Bacteria | Gram-negative bacilli | Facultative anaerobe | Aerobic media |

| Leptotrichia | Bacteria | Gram-negative bacilli | Anaerobe | Anaerobic media |

| Streptococcus salivarius | Bacteria | Gram-positive cocci | Facultative anaerobe | Brucella agar plates |

| Streptococcus bovis | Bacteria | Gram-positive cocci | Facultative anaerobe | Membrane bovis agar media |

| Coliforms | Bacteria | Gram-negative bacilli | Aerobic or facultative anaerobe | Violet red bile agar media, lauryl tryptase broth, brilliant green bile media |

| Helicobacter pylori | Bacteria | Gram-negative bacilli | Microaerophilic | Culture plate in microaerophilic jar, Brain heart infusion |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Bacteria | Gram-positive cocci | Facultative anaerobe | Mannitol salt agar media, tryptic soy agar |

| Fusobacterium species | Bacteria | Gram-negative bacilli | Anaerobe | Egg yolk agar media, brucella blood agar media, crystal violet erythromycin (CVE) agar media |

| Enterococcus Faecalis | Bacteria | Gram-positive bacilli | Facultative anaerobe | Pfizer selective enterococcus agar media |

| Bacteroides Fragilis | Bacteria | Gram-negative bacilli | Obligate anaerobe | Bacteroides Fragilis Selective media |

| Escherichia coli | Bacteria | Gram-negative bacilli | Facultative anaerobe | Luria broth, tryptic soy agar media |

| Mycobacterium avium complex | Bacteria | Gram-positive bacilli | Saprotrophic | Blood agar, mycobactin J-supplemented Herrold-egg yolk medium, Lowenstein-Jensen medium |

| Methylo bacterium radiotolerans | Bacteria | Gram-negative bacilli | Facultative methylotroph | Sheep blood agar, nutrient agar media |

| Spingomonas yanoikuyae | Bacteria | Gram-negative bacilli | Aerobe | Trypticase soy broth |

| Human papilloma virus | Virus | – | – | Tissue culture |

| Epstein–Barr virus | Virus | – | – | Chorioallantoic membrane of the chicken embryo |

| Herpes virus | Virus | – | – | Chick embryo culture |

Discussion

The microbiome of the human body consists of a broad variety of microorganisms that includes bacteria, virus, protozoa, and fungi. This microbial ecosystem shares the spaces in and on the body and creates an environment for commensal symbionts and pathobionts. The gastrointestinal tract has the largest microbial population in the human body, followed by the oral cavity. The advent of innovative molecular techniques has contributed to the isolation of approximately 700 microorganisms within the oral cavity. Recently, the conceptualization of microorganisms has changed. They have come to be considered only as pathogens rather than partners of the healthy human body (35-37).

Numerous studies have identified an interaction between the microbiome and cancer. The microbiome influences carcinogenesis using mechanisms that are independent of the immune system and inflammation. However, the most noticeable channel between the microbiome and cancer is through the immune system. It is believed that all these effects become more potent in combination and influence the initiation and progression of carcinogenesis. This systematic review was performed to identify the roles and diverse contributions of the microbiome in carcinogenesis, which will provide opportunities for the development of effective diagnostic and preventive methods (35-37).

In the present systematic review, a total of 46 articles were selected by the reviewers, and the selected articles were original research articles in which the microbiome played an important role in carcinogenesis. Several microbes can cause chronic infections and produce toxins that disturb the cell cycle and alter cell growth. These chronic infections activate cell proliferation and DNA replication via activation of cyclin D1 and the mitogen-activated kinase (MAPK) pathways, and they increase the activation of oncogenic transformation and the rate of tumor development through an increased rate of genetic mutation. Chronic infection results in intracellular accumulation of the pathogen, leading to suppression of apoptosis primarily by inactivating the retinoblastoma protein and modulating the expression of Bcl-2 family proteins. Thus, it allows the partially transformed cells to evade the self-destructive process and progress to a further level of transformation, ultimately becoming carcinogenic. The metabolism of potentially carcinogenic substances by the bacteria is another possible mechanism. The pre-existing microbes in oral cavity facilitate carcinogenesis by converting ethanol into its carcinogenic derivative, acetaldehyde. They also capable of inducing, mutagenesis, DNA damage and secondary hyperproliferation of the epithelium (38,39).

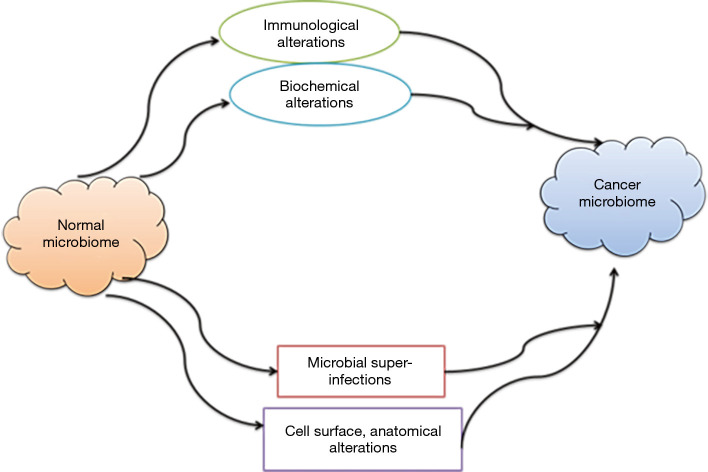

Cancer is a long-term process and is associated with changes in the body environment consisting of anatomical, physiological, biochemical, hormonal and immunological alterations (Figure 3). Hence, it is believed that changes during cancer development will also exhibit effects on the normal microbiome (40). On the other hand, the shift in the microbial community from eubiosis to dysbiosis is associated with host metabolic and cellular responses that modulate cancer risk. Various microbes play pivotal roles in preventing and protecting against cancer via modulation of inflammatory processes due to close contact with host mucosa. In cancer, due to the increase in inflammation and oxidative stress, an imbalance occurs in the normal flora and drives the formation of specific metabolites—namely, nitric oxide synthetase (NOS2), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and reactive oxygen species and an increase in cytokines such as interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. As a result, various cellular responses occur, including a decrease in apoptosis, the promotion of cellular invasion and migration, an increase in cell proliferation, macrophage polarization toward the M1 phenotype, a decrease in DNA stability, and production of carcinogens. Overall, these processes result in a shift in commensal microflora to the pathogenic state (38).

Figure 3.

The possible mechanism for alteration of normal microbiome to cancer microbiome.

In the present systematic review, it was identified that certain cancers including oral, lung, gastric, pancreatic and colon cancers have been associated with altered microbial profiles. This shift is stimulated by changes in the microenvironment that interrupt the function of the normal microbiome and lead to an altered microbial composition that mediates carcinogenesis. In the selected studies, microbes such as Candida albicans in oral cancer and F. nucleatum in colorectal cancer supported the idea of a shift in the microbiome from normal health to cancer (9-11).

According to this review, different types of cancer exhibit associations with different microbes. In the selected studies, Candida albicans, F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis and HPV were the most common organisms involved in most human cancers. Helicobacter pylori was reported to be associated with gastric cancer (31,32); F. nucleatum (22-24) with colorectal cancer; Methylobacterium radiotolerans, Sphingomonas yanoikuyae, HPV, and Epstein–Barr virus with breast cancer (26,29,33); the Mycobacterium avium complex with lung cancer (34); and Herpesvirus and candidal species with leukemia (18,41).

In oral cancer, the most commonly isolated fungal species was Candida albicans (12-21), while the most commonly isolated bacterial species were P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum (22-24) and the most commonly isolated virus was HPV (8,25,27-30).

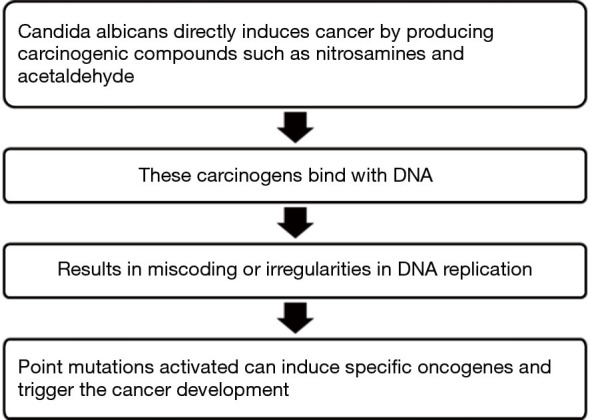

Common fungal species and cancer development

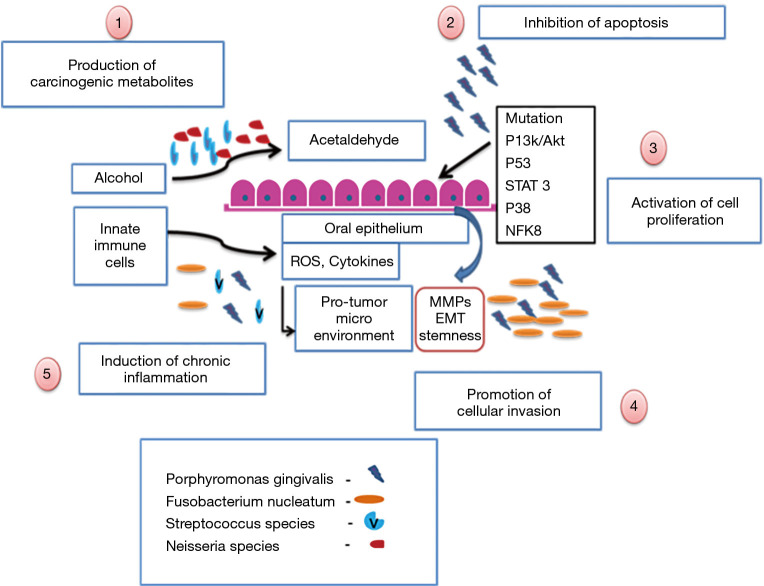

In the studies selected for this review, the most common fungal species in cancer was found to be Candida albicans. Candida albicans has the ability to colonize, penetrate and damage host tissues. These processes depend on an imbalance between host defenses and Candida albicans (Figure 4). The role of Candida in cancer development includes the following five elements:

Figure 4.

Steps in production of carcinogens and cancer development.

❖ Colonization of the epithelium;

❖ Production of carcinogens;

❖ Ability to promote carcinogenesis in initiated epithelium;

❖ Ability to metabolize procarcinogens;

❖ Capability to alter the microenvironment and induce chronic inflammation.

Colonization of the epithelium

In the presence of specific defects in the immune system, Candida albicans can colonize, penetrate and damage host tissue. There are two mechanisms involved:

❖ First is secretion of degradative enzymes such as aspartic proteases. This enzyme digests the epithelial cell surface and permit the candidal hyphae into or between epithelial cells.

❖ Second mechanism is the induction of epithelial cell endocytosis. Once the Candida albicans reach the keratinocytes, they stimulate the cells to form pseudopod-like structures that surround the fungi. Then, through the E-cadherin pathway, the cells can internalize the fungi (39).

Production of carcinogens

Ability to promote carcinogenesis in initiated epithelium

It is also proposed that candidal organisms initiate cell proliferation that can lead to clonal expansion of genetically altered cells (39).

Ability to metabolize procarcinogens

One important risk factor for the development of cancer is alcohol. In particular, the metabolic products of ethanol, including acetaldehyde, hydroxyl ethyl radicals, and ethoxy radicals, are active carcinogens. The conversion of alcohol to acetaldehyde is performed by the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase (ADH). Several studies have shown that bacteria and fungi can also be involved in this conversion process and can induce tumor development from various infections such as candidiasis.

Capability to modify the microenvironment and induce chronic inflammation

Currently, the relation among epithelial mesenchyme interaction, the role of chronic inflammatory cells and its mediators in cancer has been attaining attention. Different events may contribute to carcinogenesis and activate proteolytic enzymes that are able to degrade components of the epithelium and connective tissue. Candida albicans also secretes specific enzymes that have the capacity to degrade the basement membrane and matrix. They degrade laminin-332 and E-cadherin, which are present in the basement membrane and keratinocytes, respectively. The relation of Candida albicans to Toll-like receptors (TLR), NF-κB, production of cytokines and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) implies that Candida albicans has the potential to alter the microenvironment and produce chronic inflammation that drives cancer development (42).

Common bacterial species and cancer development

In the studies selected for this review, the most common bacteria in cancer were P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum. P. gingivalis, a bacterium that has been isolated and found to be periopathogenic, plays a significant role in cancer by developing cellular invasion. The bacterial infection stimulates the ERK1/2-Ets1, p38/HSP27, and PAR2/NF-ΚB pathways to activate pro-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression. P. gingivalis also produces gingipains and cysteine proteinase leading to retainment of the PAR2 receptor as well as cleaving of MMP-9 proenzyme converting it into the mature active form. MMP-9 disintegrates the basement membrane and extracellular matrix, promoting tumor cell migration and invasion. This allows the tumor cells to reach the lymphatic system and blood vessels thereby causing metastasis. In this manner, P. gingivalis may add to the development and progression of cancer (43-51).

F. nucleatum is another periopathogenic bacterium associated with carcinogenesis. F. nucleatum can elevate cell proliferation and migration by targeting signaling molecules such as kinases involved in cell cycle control, causing cell proliferation and migration to increase. Furthermore, the bacterium secretes MMP-9 and MMP-13 (collagenase 3) by activating p38. It also plays a significant role in tumor invasion and metastasis. Recent studies have reported that F. nucleatum, with the help of a fusobacterial adhesin known as FadA that binds to E-cadherin on colon cancer cells, activates β-catenin signaling and results in colorectal cancer. This pathway leads to increased transcriptional activity of oncogenes, Wnt, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as stimulation of cancer cell proliferation (Figure 5) (52,53).

Figure 5.

Possible mechanism of bacteria in carcinogenesis.

It is well known that P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum play a pivotal role in periodontitis. Paradoxically, the role of these bacteria in the etiology and progression of oral cancer is less known. Chronic infection in the oral cavity aids carcinogenesis by various mechanisms that include atypical activation of infiltrating immune cells, induction of DNA damage through the formation of reactive nitrogen and oxygen species, and increased levels of immunocyte-derived bioactive molecules that promote tumor progression (52).

Common viruses and cancer

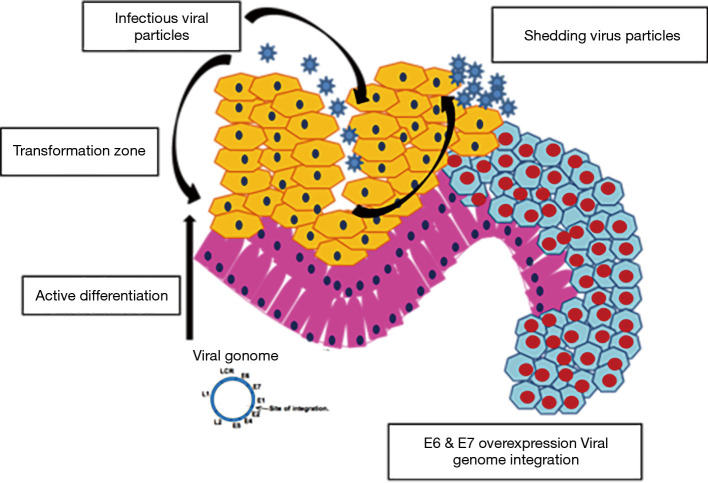

According to the present systematic review, the most common virus involved in cancer is HPV. HPVs are small, non-enveloped, icosahedral, epitheliotropic DNA tumor viruses that play important roles in carcinogenesis. The life cycle of HPV begins at microlesions in the epithelium. This features a specialized differentiation program where viral DNA synthesis and expression are linked to capsid proteins. Virions directly infect the basal layer. The overlying stratum corneum and stratum granulosum synthesize capsids and release active virions. Once virion penetration occurs, three major mechanisms become active, including plasmid, vegetative, and productive replication. Because of these mechanisms, a change in keratinocytes from the basal layer to the surface of the epithelium occurs, providing a relevant microenvironment for productive cell replication. This also helps convert the keratinocyte into a permissive cell. Once the cells undergo epithelial differentiation, vegetative replication mechanisms occur. Finally, through viral episomal DNA rupture, the HPV genome is integrated into the genome of the host cell, and the preserved E6 and E7 segments undergo transcription (Figure 6). This results in a disturbance of cell control mechanisms and increased proliferation of infected cells, promoting cancer development and progression (53,54).

Figure 6.

Mechanism of carcinogenesis induced by HPV.

Among all cancers, 20% of oral cancers and 60% to 80% of oropharyngeal cancers are attributed to HPV infection. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) confirmed in 2012 that there was sufficient evidence to associate a subtype of HPV 16 with oral cancers. In the oral cavity, approximately 12 HPV types (2, 3, 6, 11, 13, 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 52, and 57) have been associated with malignant lesions, and 24 HPV types (1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 10, 11, 13, 16, 18, 30, 31, 32, 33, 35, 45, 52, 55, 57, 59, 69, 72, and 73) with benign lesions. HPV plays a pivotal role in the etiology of oral cancer because of its morphological association with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and its capability to immortalize oral keratinocytes and bring about transformation of epithelial cells. The most commonly identified type of genetic alteration in oral cancers was found to be loss of tumor suppressor proteins such as p53, antiproliferative proteins, and the product of the retinoblastoma gene (pRb). This is mainly due to genetic mutation or interaction with viral oncoproteins such as E6/E7 of HPV. Any interruption in the activity of these proteins permits the accumulation of genetic mutations, leading to a carcinogenic phenotype.

Commonly used investigative technique

The investigatory techniques used were culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, immunofluorescence assays, fluorescence staining and pyrosequencing. Among them, the most commonly used technique for Candida was culture, which was employed in the studies of Saini et al., 2009; Saigal et al., 2011; Bakki et al., 2014; Tafvizi and Fard, 2014; Berkovits et al., 2016; de Sousa et al., 2016; Ainapur et al., 2017. The advantage of using this method is that it is conventional, easy to use and cost effective. However, different culture media were used, with SDA being the most common. The growth of organisms in culture media was verified with help of confirmatory tests such as the sugar fermentation test, chlamydospore formation and the germ tube test (9,12-15,19,20,55).

For bacteria and viruses, the most commonly used investigative technique was PCR. The studies by Kang et al., 2009; Kullander et al., 2009; Ahmed and Eltoom, 2010; Dayama et al., 2011; Farrell et al., 2012; Goot-Heah et al., 2012; Nola-Fuchs et al., 2012; Faghihloo et al., 2014; Saravani et al., 2014; Tafvizi and Fard, 2014; Xuan et al., 2014; Acharya et al., 2015; Dang et al., 2015; Mima et al., 2015; Urbaniak et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2016; Andres-Franch et al., 2017; Naushad et al., 2017; Bandhary et al., 2018 used the technique to evaluate the microbiota associated with various cancers. The advantages of using this method are its high sensitivity, accuracy, reproducibility and specificity (26-31,33,56-63).

One of the limitations of this review is that it is limited to English-language articles. Additionally, no animal studies were included in the systematic review. In view of recent advances that have brought novel, more targeted radiotherapy techniques and made new technology available to analyze the microbiome, the findings of older studies need to be interpreted cautiously.

There are several possible mechanisms—such as inflammation, metabolism and genotoxicity—by which the microbiome may regulate carcinogenesis, but there is no direct evidence for the relation between the microbiome and cancer. Research on the “oncobiome” continues to grow rapidly, but several key questions remain unanswered. On the other hand, it is becoming more apparent that the microbiome can also exert an anticancer effect through its products. Thus, researchers aim to identify and support microbes which fight cancer, thereby develop ways to eliminate those that promote development of cancer (61-63).

Conclusions

On the basis of the present review, many microbes have been found to play roles in carcinogenesis. In oral cancer, the commonly involved microbes were found to be Candida albicans, P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum and HPV. The present systematic review emphasizes that the role and diverse contributions of the microbiome in carcinogenesis will provide opportunities for the development of effective diagnostic and preventive methods. The results have clarified the link between the microbiome and cancer, promoting the development of new methods to modulate a patient’s resident microbial communities to improve their prognosis and treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Translational Cancer Research for the series “Oral Pre-cancer and Cancer”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2020.02.11). The series “Oral Pre-cancer and Cancer” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. KHA served as an unpaid Guest Editor of the series. SP served as an unpaid Guest Editor of the series and serves as an unpaid Editorial Board Member of Translational Cancer Research from Jul 2018 to Jun 2020. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Kudo Y, Tada H, Fujiwara N, et al. Oral environment and cancer. Genes Environ 2016;38:13. 10.1186/s41021-016-0042-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwabe RF, Jobin C. The microbiome and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2013;13:800-12. 10.1038/nrc3610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalton-Griffin L, Kellam P. Infectious causes of cancer and their detection. J Biol 2009;8:67. 10.1186/jbiol168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lax AJ, Thomas W. How bacteria could cause cancer: one step at a time. Trends Microbiol 2002;10:293-9. 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)02360-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Cotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S. editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available online: www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almståhl A, Finizia C, Carlén A, et al. Mucosal microflora in head and neck cancer patients. Int J Dent Hyg 2018;16:459-66. 10.1111/idh.12348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:24-35. 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakki SR, Kantheti LP, Kuruba KK, et al. Candidal carriage, isolation and species variation in patients undergoing radiotherapy and chemotherapy for head and neck tumours. J NTR Univ Health Sci 2014;3:28-34. 10.4103/2277-8632.128427 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf A, Moissl-Eichinger C, Perras A, et al. The salivary microbiome as an indicator of carcinogenesis in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A pilot study. Sci Rep 2017;7:5867. 10.1038/s41598-017-06361-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamura K, Baba Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Human microbiome Fusobacterium nucleatum in esophageal cancer tissue is associated with prognosis. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:5574-81. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alnuaimi AD, Wiesenfeld D, O’Brien-Simpson NM, et al. Oral Candida colonization in oral cancer patients and its relationship with traditional risk factors of oral cancer: a matched case-control study. Oral Oncol 2015;51:139-45. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkovits C, Tóth A, Szenzenstein J, et al. Analysis of oral yeast microflora in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Springer Plus 2016;5:1257. 10.1186/s40064-016-2926-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ainapur MMAR, Mahesh P, Kumar KV, et al. An in vitro study of isolation of candidal strains in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients undergoing radiation therapy and quantitative analysis of the various strains using CHROMagar. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2017;21:11-7. 10.4103/0973-029X.203793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Sousa LVNF, Santos VL, de Souza Monteiro A, et al. Isolation and identification of Candida species in patients with orogastric cancer: susceptibility to antifungal drugs, attributes of virulence in vitro and immune response phenotype. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:86. 10.1186/s12879-016-1431-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jahanshahi G, Shirani S. Detection of Candida albicans in oral squamous cell carcinoma by fluorescence staining technique. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2015;12:115-20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain M, Shah R, Chandolia B, Mathur A, et al. The oral carriage of Candida in oral cancer patients of Indian origin undergoing radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:ZC17-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasan AH, AL-Jubouri MH. Isolation of candida Spp. from patients with different types of leukemia who suffered oral candidiasis due to their weekend immune system. J Pharm Chem Biol Sci 2015;3:79-83. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saigal S, Bhargava A, Mehra SK, et al. Identification of Candida albicans by using different culture medias and its association in potentially malignant and malignant lesions. Contemp Clin Dent 2011;2:188-93. 10.4103/0976-237X.86454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saini S, Saini SR, Katiyar R, et al. The use of tobacco and betel leaf and its effect on the normal microbial flora of oral cavity. Pravara Medical Review 2009;1:47-85. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonalika WG, Tayaar SA, Bhat KG, et al. Oral microbial carriage in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients at the time of diagnosis and during radiotherapy–a comparative study. Oral Oncol 2012;48:881-6. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mima K, Sukawa Y, Nishihara R, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and T cells in colorectal carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2015;1:653-61. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Y, He H, Xu H, et al. Association of oncogenic bacteria with colorectal cancer in South China. Oncotarget 2016;7:80794-802. 10.18632/oncotarget.13094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weir TL, Manter DK, Sheflin AM, et al. Stool microbiome and metabolome differences between colorectal cancer patients and healthy adults. PLoS One 2013;8:e70803. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed HG, Eltoom FM. Detection of Human Papilloma virus Types 16 and 18 among Sudanese patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. The Open Cancer Journal. 2010;3:130-4. 10.2174/1874079001003010130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandhary SK, Shetty V, Saldanha M, et al. Detection of Human Papilloma Virus and Risk Factors among Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Attending a Tertiary Referral Centre in South India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2018;19:1325-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dang J, Feng Q, Eaton KD, et al. Detection of HPV in oral rinse samples from OPSCC and non-OPSCC patients. BMC Oral Health 2015;15:126. 10.1186/s12903-015-0111-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goot-Heah K, Kwai-Lin T, Froemming GR, et al. Human papilloma virus 18 detection in oral squamous cell carcinoma and potentially malignant lesions using saliva samples. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012;13:6109-13. 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.12.6109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naushad W, Surriya O, Sadia H, et al. Prevalence of EBV, HPV and MMTV in Pakistani breast cancer patients: a possible etiological role of viruses in breast cancer. Infect Genet Evol 2017;54:230-7. 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nola-Fuchs P, Vucicevic Boras V, Plecko V, et al. The prevalence of human papillomavirus 16 and Epstein-Barr virus in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Acta clinica Croatica 2012;51:609-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dayama A, Srivastava V, Shukla M, et al. Helicobacter pylori and oral cancer: possible association in a preliminary case control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011;12:1333-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kafle B, Bhandari RS, Lakhey PJ, et al. Association between helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 2014;52:757-63. 10.31729/jnma.2726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xuan C, Shamonki JM, Chung A, et al. Microbial dysbiosis is associated with human breast cancer. PLoS One 2014;9:e83744. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lande L, Peterson DD, Gogoi R, et al. Association between pulmonary mycobacterium avium complex infection and lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:1345-51. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31825abd49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhatt AP, Redinbo MR, Bultman SJ, et al. The role of the microbiome in cancer development and therapy. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:326-44. 10.3322/caac.21398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajagopala SV, Vashee S, Oldfield LM, et al. The human microbiome and cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2017;10:226-34. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Botero LE, Delgado-Serrano L, Cepeda Hernandez ML, et al. The human microbiota: the role of microbial communities in health and disease. Acta Biologica Colombiana 2016;21:5-15. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dagli N, Dagli R, Darwish S, et al. Oral microbial shift: factors affecting the microbiome and prevention of oral disease. J Contemp Dent Pract 2016;17:90-6. 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohd Bakri M, Mohd Hussaini H, Rachel Holmes A, et al. Revisiting the association between candidal infection and carcinoma, particularly oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Microbiol 2010;2:5780. 10.3402/jom.v2i0.5780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan AA, Shrivastava A, Khurshid M, et al. Normal to cancer microbiome transformation and its implication in cancer diagnosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1826:331-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steininger C, Rassenti LZ, Vanura K, et al. Relative seroprevalence of human herpes viruses in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Eur J Clin Invest 2009;39:497-506. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02131.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurkivuori J, Salaspuro V, Kaihovaara P, et al. Acetaldehyde production from ethanol by oral streptococci. Oral Oncol 2007;43:181-6. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chocolatewala N, Chaturvedi P, Desale R, et al. The role of bacteria in oral cancer. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2010;31:126-31. 10.4103/0971-5851.76195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khajuria N, Metgud R. Role of bacteria in oral carcinogenesis. Indian J Dent 2015;6:37-43. 10.4103/0975-962X.151709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghosh DS, Chaudhary DM, Patil DS, et al. Quantification of viable aerobic bacteria in oral squamous cell carcinoma tissue – a microbiological approach. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 2014;13:115-8. 10.9790/0853-1374115118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cankovic M, Bokor-Bratic M, Loncar J, et al. Bacterial flora on the surface of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Oncol 2013;21:62-4. 10.2298/AOO1302062C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu J, Han S, Chen Y, et al. Variations of tongue coating microbiota in patients with gastric cancer. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:173729. 10.1155/2015/173729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metgud R, Gupta K, Gupta J, et al. Exploring bacterial flora in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a microbiological study. Biotech Histochem 2014;89:153-9. 10.3109/10520295.2013.831120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharma P, Gawande M, Chaudhary M, et al. Evaluation of Prevalence of Bacteria Helicobacter pylori in Potentially Malignant Disorders and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. World J Dent 2015;6:82-6. 10.5005/jp-journals-10015-1319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsai CE, Chiu CT, Rayner CK, et al. Associated factors in Streptococcus bovis bacteremia and colorectal cancer. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2016;32:196-200. 10.1016/j.kjms.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zaki AN, Kadum AD, Mousa NK, et al. Cancer infection and its relationship with Streptococcus mitis increasing numbers in human mouth. Int J Eng Sci Res 2014;5:88. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitmore SE, Lamont RJ. Oral bacteria and cancer. PLoS Pathog 2014;10:e1003933. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Binder Gallimidi A, Fischman S, Revach B, et al. Periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum promote tumor progression in an oral-specific chemical carcinogenesis model. Oncotarget 2015;6:22613-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim SM. Human papilloma virus in oral cancer. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;42:327-36. 10.5125/jkaoms.2016.42.6.327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tafvizi F, Fard ZT. Detection of human cytomegalovirus in patients with colorectal cancer by nested-PCR. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:1453-7. 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.3.1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kang MS, Oh JS, Kim HJ, et al. Prevalence of oral microbes in the saliva of oncological patients. J Bacteriol Virol 2009;39:277-85. 10.4167/jbv.2009.39.4.277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kullander J, Forslund O, Dillner J, et al. Staphylococcus aureus and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:472-8. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farrell JJ, Zhang L, Zhou H, et al. Variations of oral microbiota are associated with pancreatic diseases including pancreatic cancer. Gut 2012;61:582-8. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Faghihloo E, Saremi MR, Mahabadi M, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Epstein–Barr Virus-associated Gastric Cancer in Iran. Arch Iran Med 2014;17:767-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andres-Franch M, Galiana A, Sanchez-Hellin V, et al. Streptococcus gallolyticus infection in colorectal cancer and association with biological and clinical factors. PLoS One 2017;12:e0174305. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Acharya S, Ekalaksananan T, Vatanasapt P, et al. Association of Epstein-Barr virus infection with oral squamous cell carcinoma in a case–control study. J Oral Pathol Med 2015;44:252-7. 10.1111/jop.12231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saravani S, Miri-Moghaddam E, Sanadgol N, et al. Human Herpesvirus-6 and Epstein–Barr Virus Infections at Different Histopathological Grades of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Int J Prev Med 2014;5:1231-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Urbaniak C, Gloor GB, Brackstone M, et al. The microbiota of breast tissue and its association with breast cancer. Appl Environ Microbiol 2016;82:5039-48. 10.1128/AEM.01235-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]