Abstract

Molecular characterization of 53 U.S. and Canadian Corynebacterium diphtheriae isolates by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, ribotyping, and random amplified polymorphic DNA showed that strains with distinct molecular subtypes have persisted in the United States and Canada for at least 25 years. These strains are endemic rather than imported from countries with current endemic or epidemic diphtheria.

In the 1970s, nearly 1,300 cases of diphtheria in the United States (5) and 444 in Canada (3, 6, 9, 19) were reported. Since the mid-1980s, the number of cases in both countries has declined to fewer than 50 (2, 4, 11, 20). In 1996, isolation of toxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae from the blood of an American Indian woman living in the Northern Plains region of the United States prompted public health officials to conduct enhanced diphtheria surveillance in the patient's community, resulting in the recovery of 10 C. diphtheriae isolates (4, 16). To assess the similarity of the U.S. and Canadian strains and their possible endemic persistence in North America over the past 25 years, we molecularly characterized the U.S. surveillance isolates from 1996, isolates from the same geographic region collected approximately 20 years earlier, and isolates from Ontario obtained from 1958 to 1998.

Isolates. (i) U.S. isolates.

Detailed information regarding the U.S. surveillance and archival isolates is provided by Popovic et al. (16). Thirty-three isolates were included in this study: a single isolate from the blood culture of the index patient, 10 isolates recovered from the subsequent enhanced diphtheria surveillance, 17 archival isolates collected from diphtheria patients and carriers in South Dakota from 1973 to 1983, and 5 archival isolates from four other states (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of C. diphtheriae strains isolated in the United States and Canada from 1973 to 1998

| Ribotypea | RAPD pattern | Strain designation | Yr | Country (state) | ETb | Biotypec | Toxigenicity

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elek | PCR | |||||||

| M11a | 1 | C67 | 1977 | Canada | 271 | G | + | + |

| 1 | C68 | 1977 | Canada | 272 | G | + | + | |

| 1 | C70 | 1977 | Canada | 271 | G | + | + | |

| 1 | C72 | 1976 | Canada | 272† | G | + | + | |

| 2 | E8277 | 1980 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 215† | G | + | + | |

| 3 | D7643 | 1979 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 215† | G | + | + | |

| 1 | C4943 | 1973 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 215† | G | + | + | |

| 2 | E5276 | 1973 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 218† | G | + | + | |

| 1 | E5449 | 1979 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 40† | G | + | + | |

| 1 | G4218 | 1978 | U.S. (Colo.) | 34† | G | + | + | |

| M11b | 4 | C63 | 1977 | Canada | 267† | M | − | − |

| 5 | C66 | 1977 | Canada | 270† | M | − | − | |

| 4 | C74 | 1977 | Canada | 276† | M | − | − | |

| 6 | C59 | 1998 | Canada | 228† | B | − | − | |

| 6 | C62 | 1994 | Canada | 266† | M | + | + | |

| 6 | C60 | 1998 | Canada | 264† | B | + | + | |

| 6 | C75 | 1996 | Canada | 277† | B | + | + | |

| 6 | C76 | 1995 | Canada | 278† | B | + | + | |

| 6 | C77 | 1995 | Canada | 278† | B | + | + | |

| 6 | PR110 | 1996 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 228† | M | + | + | |

| 6 | PR115 | 1996 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 228† | M | + | + | |

| 6 | UT 6–96 | 1996 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 226 | M | + | + | |

| M11c | 6 | C5276 | 1973 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 217† | M | + | + |

| M11d | 8 | PR 79 | 1996 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 225 | G | + | + |

| 8 | PR 109 | 1996 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 221† | G | + | + | |

| M1 | 15 | C71 | 1976 | Canada | 274 | G | − | − |

| 17 | C73 | 1977 | Canada | 275 | I | − | − | |

| M1a | 9 | E5340 | 1979 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 219† | M | − | + |

| 9 | E7798 | 1980 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 220† | M | − | + | |

| 9 | E8392 | 1980 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | ND | M | − | + | |

| 9 | E9026 | 1980 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | ND | M | − | + | |

| 9 | F1788 | 1981 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | ND | M | − | + | |

| 9 | F1803 | 1981 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | ND | M | − | + | |

| 9 | F2726 | 1982 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | ND | M | − | + | |

| 9 | F4306 | 1983 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | ND | M | − | + | |

| 10 | E9134 | 1980 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | ND | M | − | + | |

| 9 | PR 20 | 1996 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 222† | M | − | + | |

| 9 | PR 101 | 1996 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 221† | M | − | + | |

| 9 | PR 130 | 1996 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 229† | M | − | + | |

| M7a | 7 | C5214 | 1973 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 216† | M | − | − |

| 16 | G4219 | 1978 | U.S. (Alaska) | 35† | M | + | + | |

| 16 | G4220 | 1978 | U.S. (Alaska) | 35† | M | + | + | |

| M15 | 11 | D7920 | 1979 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 38 | I | + | + |

| 11 | G4221 | 1977 | U.S. (N.Mex.) | 36 | I | + | + | |

| M16 | 12 | G4217 | 1979 | U.S. (Calif.) | 33 | M | + | + |

| G3 | 14 | C69 | 1977 | Canada | 273 | G | − | − |

| G3a | 13 | PR 26 | 1996 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 223 | G | − | − |

| G3b | 13 | PR 120 | 1996 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 230 | G | − | − |

| G5 | 2 | PR 75 | 1996 | U.S. (S.Dak.) | 224 | G | + | + |

| U1∗ | 18 | C65 | 1977 | Canada | 269 | M | − | − |

| U2∗ | 19 | C64 | 1977 | Canada | 268 | B | − | − |

| U3∗ | 20 | C78 | 1986 | Canada | 279 | B | − | − |

| U4∗ | 21 | C61 | 1958 | Canada | 265† | M | + | + |

Ribotyping designations are based on ribotypes previously documented by Popovic et al. (17). ∗, unique ribotype.

† ET within the ET 215 complex; ND, not done.

M, mitis; B, belfanti; G, gravis; I, intermedius.

(ii) Canadian isolates.

Twenty C. diphtheriae strains isolated from 1958 to 1998 from patients in Ontario with upper respiratory tract infections were assayed.

Identification and biotyping were performed according to current World Health Organization recommendations (10). All strains were stored in sterile defibrinated sheep blood at −70°C until needed.

Toxigenicity status.

The Elek test was performed on all strains as previously described (10).

PCR for detection of the diphtheria toxin gene, tox.

All isolates were assayed by PCR for the presence of both the A and B subunits of the tox gene (15).

Molecular subtyping. (i) Ribotyping.

DNA was extracted from all 53 isolates using the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Inc, Minneapolis, Minn.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequent ribotyping steps were performed as previously described (16).

(ii) RAPD.

All isolates were subjected to random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis as previously described (16). All strains were assayed using primer 3 provided in the Ready-to-Go RAPD kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.).

(iii) MEE.

Forty-six of the isolates were assayed by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MEE) as previously described (17).

Results and discussion.

Among the U.S. surveillance and archival isolates, 20 were biotype mitis, 11 were biotype gravis, and 2 were biotype intermedius (Table 1).

Among the Canadian isolates, seven were biotype belfanti, six were biotype mitis, six were biotype gravis, and one was biotype intermedius (Table 1).

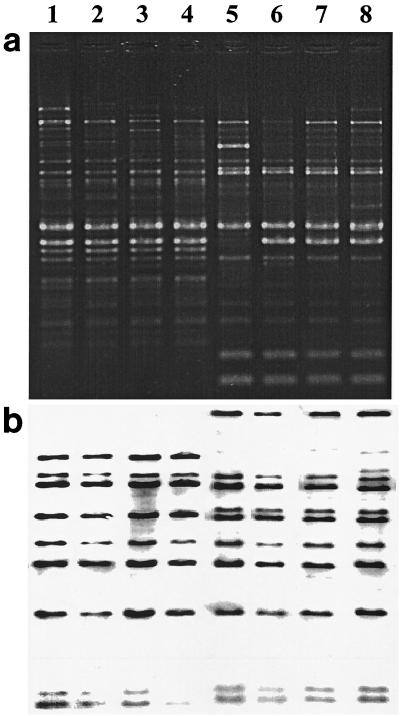

Seventeen ribotypes were identified (Table 1), 11 of which were previously described (16). A difference of one band was recognized as an individual ribotype. Two ribotypes, M11a and M11b, were shared by a large proportion of the U.S. and Canadian strains (22 of 53). Ribotype M11a was seen in four Canadian strains (from 1976 and 1977) and six U.S. strains (five from South Dakota [1973 to 1980] and one from Colorado [1978]) (Fig. 1). Twelve M11b strains were isolated both in the United States and Canada over 20 years apart (1977 to 1998) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

RAPD (a) and ribotype (b) patterns of four U.S. and four Canadian strains isolated from 1973 to 1998. Lane 1, C67 (strain designation), isolated in Canada, 1977 (year of isolation), gravis (biotype), toxigenic; lane 2, C72, Canada, 1976, gravis, toxigenic; lane 3, C4943, United States (South Dakota), 1973, gravis, toxigenic; lane 4, E5449, United States (South Dakota), 1979, gravis, toxigenic; lane 5, C74, Canada, 1977, mitis, nontoxigenic; lane 6, C59, Canada, 1998, belfanti, nontoxigenic; lane 7, PR110, United States (South Dakota), 1996, mitis, toxigenic; lane 8, C5276, United States (South Dakota), mitis, toxigenic.

Twenty-one RAPD patterns were identified (Table 1). A difference of one band, using only the major bands (those of strong intensity and consistency), was recognized as an individual RAPD pattern. Two common RAPD patterns were identified in both the U.S. and Canadian isolates (Fig. 1). RAPD pattern 1 was seen in four Canadian isolates (1976 to 1977) and three U.S. isolates (1973 to 79). These seven isolates also had the same ribotype, M11a. The second common pattern, pattern 6, was identified in six Canadian isolates (1994 to 98) and four U.S. isolates (three surveillance [1996] and one archival [1973]) (Fig. 1), and all but one were of ribotype M11b.

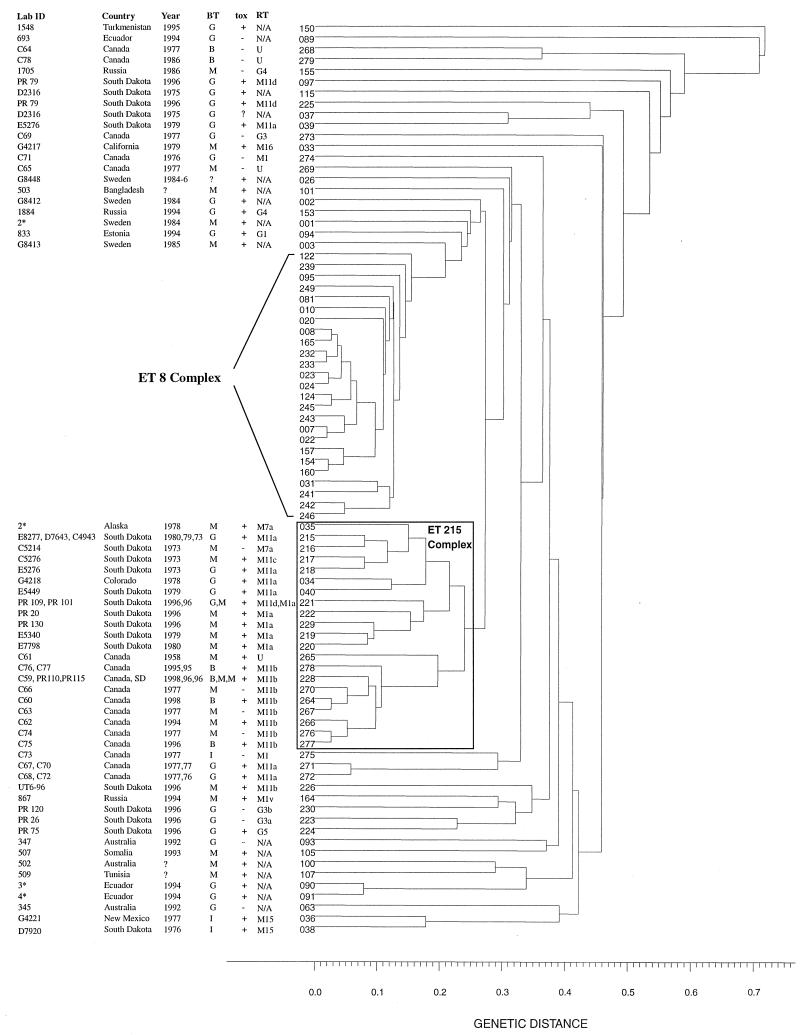

Both U.S. and Canadian strains showed greater genetic diversity by MEE. Among the 46 strains tested (15 U.S. archival, 11 U.S. surveillance, and 20 Canadian), 37 electrophoretic types (ETs) were identified (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Twenty-eight isolates (10 Canadian and 18 U.S.) belonging to 21 distinct ETs were clustered within a genetic distance of <0.25, expanding the previously described ET 215 complex (16). Eleven strains (2 U.S. and 9 Canadian) had the same ribotype (M11b), and eight of these had the same RAPD pattern (pattern 6). The 10 Canadian strains in the ET 215 complex formed a subcluster of nine ETs that, with the exception of ET 228, were unique to Canadian strains. In addition, with the exception of one strain, all strains in this subcluster had the same ribotype (M11b).

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram showing the genetic relatedness of 85 ETs of C. diphtheriae isolates collected from around the world from 1973 to 1998. ID, identifying designation; Year, year of isolation; BT, biotype; tox, toxigenicity status; RT, ribotype; B, belfanti; M, mitis; G, gravis; N/A, information not available; ∗, number of strains with the same ET. The ET 8 complex is associated with the diphtheria epidemic in Russia and the New Independent States which occurred from 1990 to 1998. All strains in the ET 8 complex, with one exception, are biotype gravis and are toxigenic.

Previous reports of the excellent correlation between MEE, ribotyping, and epidemiologic data prompted us to use these methods in our study (8, 17; A. De Zoysa, A. Efstratiou, R. C. George, A. McNiff, J. Vuopio-Varkila, I. Mazurova, G. Tseneva, W. Thilo, C. Andronescu, and C. Roure, Prog. Abstr. 2nd Int. Meet. Eur. Lab. Working Group Diphtheria, p. 22, 1995). The inclusion of the Canadian strains has expanded the previously documented ET 215 complex to include 21 ETs and 28 isolates (previously 12 ETs and 15 isolates) (16). Unlike the ET 8 complex, which is associated with the recent epidemic in Russia and the former Soviet Republics (New Independent States) and contains only biotype gravis strains (17), the ET 215 complex contains strains of biotypes gravis, mitis, and belfanti. The existence of toxigenic biotype belfanti strains is unusual because strains of this biotype are generally nontoxigenic (1). Interestingly, isolation of toxigenic strains of biotype belfanti was reported among the First Nations communities in northeastern Ontario between 1994 and 1997 (F. E. Cahoon, S. Brown, and F. Jamieson, Abstr. 37th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. K-171, 1997). The diversity of phenotypic and genotypic markers of the strains within the ET 215 complex suggests its steady persistence with subtle changes over time. The subtyping data strongly indicate that these strains were not the result of importation, as they were not of the ribotypes (G1 and G4) or RAPD patterns (G1/4) which prevailed among the epidemic Russian strains. Three Canadian strains, isolated several years before the onset of the Russian epidemic, had ribotypes (M1 and G3) which were rarely observed among Russian strains in the preepidemic period.

Conclusion.

Molecular characterization of the U.S. and Canadian C. diphtheriae strains indicates that they have persisted in these areas for at least 25 years and are endemic to these regions rather than having been imported from countries with current endemic or epidemic diphtheria. Despite the virtual elimination of diphtheria in the United States and Canada, toxigenic strains continue to circulate in some communities within the two countries. This long-standing circulation of toxigenic C. diphtheriae, in light of reports indicating that between 20 and 60% of some population groups, particularly adults, lack protective levels of diphtheria toxin antibodies (7, 12–14, 18), poses a potentially significant risk to public health and could result in the reemergence of diphtheria in the two countries.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bezjak V. Differentation of Corynebacterium diphtheriae of the mitis type found in diphtheria and ozaena. Antonie Leeuwenhoek J Microbiol Serol. 1954;20:269–271. doi: 10.1007/BF02543729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisgard K, Hardy I, Popovic T, Strebel P, Wharton M, Chen R, Hadler S. Respiratory diphtheria in the United States, 1980–1995. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:787–791. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.5.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bollegraaf E. Diphtheria in Canada, 1977–1987. Can Dis Wkly Rep. 1988;14 (18):73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Toxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae—Northern Plains Indian community, August–October 1996. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46:506–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen R T, Broome C V, Weinstein R A, Weaver R, Tsai T F. Diphtheria in United States, 1971–1981. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:1393–1397. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.12.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooperman E M. Diphtheria: a continuing hazard. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;116:1226–1227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crossley K, Irvine P, Warren J B, Lee B K, Mead K. Tetanus and diphtheria immunity in urban Minnesota adults. JAMA. 1979;242:2298–2300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Zoysa A, Efstratiou A, George R C, Jahkola M, Vuopio-Varkila J, Deshevoi S, Tseneva G, Rikushin Y. Molecular epidemiology of Corynebacterium diphtheriae from northwestern Russia and surrounding countries studied by using ribotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1080–1083. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1080-1083.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon J M S. Diphtheria in North America. J Hyg. 1984;93:419–432. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400065013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Efstratiou A, Maple P A. WHO manual for the laboratory diagnosis of diphtheria. Reference no. ICP-EPI 038(C). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Canada. Canadian national report on immunization. 1998. Paediatr Child Health. 1999;4:16C. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klouche M, Luhmann D, Kirchner H. Low prevalence of diphtheria antitoxin in children and adults in northern Germany. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:682–685. doi: 10.1007/BF01690874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koblin B A, Townsend T R. Immunity to diphtheria and tetanus in inner-city women of childbearing age. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1297–1298. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.9.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maple P A, Efstratiou A, George R C, Andrews N J, Sesardic D. Diphtheria immunity in UK blood donors. Lancet. 1995;345:963–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90705-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikhailovich V M, Melnikov V G, Mazurova I K, Wachsmuth I K, Wenger J D, Wharton M, Nakao H, Popovic T. Application of PCR for detection of toxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae strains isolated during the Russian diphtheria epidemic, 1990 through 1994. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3061–3063. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.3061-3063.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popovic T, Kim C, Reiss J, Reeves M, Nakao H, Golaz A. Use of molecular subtyping to document long-term persistence of Corynebacterium diphtheriae in South Dakota. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1092–1099. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1092-1099.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popovic T, Kombarova S, Reeves M, Nakao H, Mazurova I K, Wharton M, Wachsmuth I K, Wenger J D. Molecular epidemiology of diphtheria in Russia, 1985–1994. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1064–1072. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss B P, Strassburg M A, Feeley J C. Tetanus and diphtheria immunity in an elderly population in Los Angeles County. Am J Public Health. 1983;73:802–804. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.7.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young T K. Endemicity of diphtheria in an Indian population in Northwestern Ontario. Can J Public Health. 1984;75:310–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan L, Lau W, Thipphawong J, Kasenda M, Xie F, Bevilacqua J. Diphtheria and tetanus immunity among blood donors in Toronto. Can Med Assoc J. 1997;156:985–990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]