PURPOSE

Because of the negative impact of cancer treatment on female sexual function, effective treatments are warranted. The purpose of this multisite study was to evaluate the ability of two dose levels of extended-release bupropion, a dopaminergic agent, to improve sexual desire more than placebo at 9 weeks, measured by the desire subscale of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), and to evaluate associated toxicities.

METHODS

Postmenopausal women diagnosed with breast or gynecologic cancer and low baseline FSFI desire scores (< 3.3), who had completed definitive cancer therapy, were eligible. Women were randomly assigned to receive 150 mg or 300 mg once daily of extended-release bupropion or a matching placebo. t-tests were performed on the FSFI desire subscale to evaluate whether there was a significantly greater change from baseline to 9 weeks between placebo and each bupropion arm as the primary end point. Sixty-two patients per arm provided 80% power using a one-sided t-test.

RESULTS

Two hundred thirty women were randomly assigned from 72 institutions through the NRG Oncology NCORP network. At 9 weeks, there were no statistically significant differences in change of the desire subscale scores between groups; participants in all three arms reported improvement. The mean changes for each arm were placebo 0.62 (standard deviation [SD] = 1.18), 150-mg once daily bupropion 0.64 (SD = 0.95), and 300-mg once daily bupropion 0.60 (SD = 0.89). Total and subscale scores on the FSFI were low throughout the study, indicating dysfunction in all groups.

CONCLUSION

Bupropion was not more effective than placebo in improving the desire subscale of the FSFI. Subscale and total scores of the FSFI demonstrated dysfunction throughout the 9 weeks of the study. More research is needed to support sexual function in female cancer survivors.

INTRODUCTION

According to the American Cancer Society,1 there will be 22 million cancer survivors by 2030, with more than half being females. Of the female survivors, 59% have been diagnosed with breast or some form of gynecologic cancer.1 Addressing chronic negative sequelae for women in the aftermath of a cancer diagnosis and treatment is a health imperative.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Is there a tolerable dose of bupropion that can improve sexual desire in female breast or gynecologic cancer survivors compared with a placebo?

Knowledge Generated

Neither 150 nor 300 mg of extended-release bupropion once daily improved sexual desire, as measured by the desire subscale of the Female Sexual Function Index, more than a placebo. Using the PRO-CTCAE, women receiving 300 mg of bupropion once daily reported more headaches at 7 weeks; otherwise, toxicities did not significantly differ between bupropion and placebo.

Relevance

Unless additional supportive evidence is generated, bupropion is not recommended to improve libido in women with breast or gynecologic cancer.

One negative consequence of treatment in some types of cancers is decreased sexual health, particularly for women with estrogen-sensitive tumors requiring estrogen deprivation. Sexual health is a multidimensional concept that encompasses aspects such as vulvovaginal health (lubrication and dryness and/or discomfort), sexual desire (libido), satisfaction, body image, and orgasm.2-4

Loss of sexual desire, a prevalent concern, is defined as a lack of motivation to engage in sexual activity and is generally thought of as a cognitive response to stimuli.5 Although low sexual desire is somewhat prevalent (up to 33%) in the general population,6,7 descriptive studies of female cancer survivors with general population comparison groups demonstrate that distress and concerns about low sexual desire are more prevalent in survivors, with 50%-70% of female cancer survivors reporting loss of desire.8-10 In a longitudinal study of 457 women with breast cancer, at 18 months after treatment, sexual desire was rated a worse problem than sexual function, satisfaction, or activity in both women who were sexually active and those who were not.11 Unfortunately, practice guidelines for aspects of sexual health including desire in female cancer survivors lack evidence-based recommendations.12,13

Female cancer survivors may experience two physiologic sequelae that can increase their risk of experiencing a loss of sexual desire; these are estrogen deprivation and generalized inflammation. Both of these issues may be linked to dopamine insufficiencies.14-18 Physiologic data from animals and humans link dopamine to reward stimuli, motivation, and reward centers that are critical to sexual desire.14,15,19 Therefore, dopamine is considered a critical neuromodulator for excitatory pathways involved in the sexual response and drugs that improve dopamine function are potential candidates to improve sexual desire.20

There are data to support the ability of dopaminergic agents to positively affect sexual desire. Flibanserin, a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, was approved for hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 201521 on the basis of three clinical trials, none of which included women with a history of cancer.22-24 Bupropion is another dopaminergic agent that has been in clinical use since 1989 and is an antidepressant, which inhibits dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake.25 It is approved for seasonal affective disorder, major depressive disorder, and smoking cessation.25,26 There are preliminary data supporting its use for improved sexual desire, which serve as the rationale for the development of a phase II trial to evaluate whether bupropion can improve sexual desire and/or energy in female cancer survivors without causing undesirable side effects.27-33

The primary aim of this multisite, double-blind, placebo-controlled study was to evaluate the ability of two dose levels of extended-release bupropion, 150 mg or 300 mg once daily, to improve sexual desire more than a placebo at 9 weeks (8 weeks on the target dose) as measured by the desire subscale of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI).34,35 The secondary aim was to evaluate the side effects of 150 mg and 300 mg once daily extended-release bupropion and differentiate these side effects from those observed in the placebo arm. Secondary outcomes include patient-reported sexual function, fatigue, dyspareunia, and the participant's perception of change and risk versus benefit.

METHODS

Eligibility

Postmenopausal women who had a diagnosis of breast or gynecologic cancer and had completed definitive therapy (surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy) at least 180 days ago were eligible if they scored below 3.3 on the desire subscale of the FSFI.35 Women could be on endocrine or maintenance trastuzumab therapy. Women with an active diagnosis of depression or anxiety, on oral or transdermal estrogen, or who had stage IV cancer were excluded from participation. Women were allowed to be treated with vaginal estrogen as long as the dose was less than the equivalent of 7.5 mcg of estradiol daily and had been using vaginal estrogen for at least 30 days without plans to stop treatment during the study. Concurrent use of tamoxifen, bupropion, flibanserin, or drugs metabolized by the CYP2D6 pathway was not allowed. All participants signed informed consent before enrolling on the study. This study was reviewed and approved by the National Cancer Institute's Central Institutional Review Board (IRB) and by the IRBs of the participating sites.

Study Design and Intervention

NRG Oncology's NRG-CC004 (NCT03180294), a phase II trial, stratified participants by current selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use (yes v no), prior pelvic treatment (none v pelvic surgery and/or pelvic radiation therapy), and aromatase inhibitor use (yes v no) and randomly assigned participants at 1:1:1 using permuted block random assignment to receive a 150 mg once daily target dose of bupropion XL, a 300 mg once daily target dose of bupropion XL, or placebo for 8 weeks. At week 1, participants were started at the lowest dose of 150 mg and increased to their target dose of 150 mg or 300 mg at week 2, all delivered once daily. Week 10 was used to titrate participants off the drug. Participants and their physicians were supplied with three bottles (A, B, and C) to maintain the blinding. Depending on the treatment assigned, bottles could contain either active drug or placebo. Bupropion was over-encapsulated such that the placebo and both doses of bupropion looked identical.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this study was the change from baseline to 9 weeks on the desire subscale of the FSFI, which is a well-validated measure in English, arguably the gold standard measure for sexual function in women.34,36,37 The FSFI is a relatively brief multidimensional measure36,37 (19 items) and includes six subscales: desire, arousal, satisfaction, orgasm, lubrication, and pain. Each subscale can be scored separately and combined for a total FSFI score. The desire subscale consists of two items (frequency and intensity) and has a range of 1.2-6 when scored, and higher scores indicate more desire. The FSFI was completed at baseline and 5 and 9 weeks from the start of treatment.

Adverse events were measured by the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4 and the patient-reported outcome version, PRO-CTCAE, to capture provider-assessed and patient-assessed adverse events. Solicited adverse events that were collected from patients included dizziness, insomnia, headache, dry mouth, anorexia, nausea, constipation, tremor, nasal congestion, and pharyngolaryngeal pain. Adverse events were evaluated at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 5, 7, and 9 from the start of treatment.

A second measure of sexual interest and satisfaction was used to corroborate FSFI results. The PROMIS initiative or Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System is supported by the National Institute of Health to improve measurement science related to self-reported health measures. The sexual function and satisfaction measure has good content, face, discriminant, and convergent validity.38 In particular, for women,38 it demonstrates good convergent validity with the FSFI. We used the PROMIS interest and global satisfaction scales, which were completed at baseline and weeks 5 and 9 from the start of treatment. The range of scores on the sexual interest items was 4-20, and for global sexual satisfaction, it was 6-30, with higher scores being more positive.

Fatigue, a secondary outcome, was measured with the PROMIS short form 8a, which has been well validated.39 It contains eight questions related to severity, bother, and activity interference related to fatigue in the past 7 days. Responses are not at all to very much for six questions, and never to always for two questions. Raw scores range from 8 to 40 but are converted to standardized scores called T-scores.

There were two additional measures completed only at baseline as they represent important potential predictors of sexual function. These were the Impact of Treatment Scale (ITS),40 which measures body image stress, and the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS),41,42 which is a measure of relationship satisfaction. Scores on the ITS range from 0 to 65, with higher scores indicating more distress. For the RDAS, scores range from 0 to 60 where lower scores indicate less relationship satisfaction and scores of 47 and below indicate relationship distress.41,42

In addition, two investigator-developed questions were included to evaluate overall satisfaction with treatment and risk versus benefit. Both these questions were only asked at week 9 from the start of treatment. The first question was, “How satisfied are you with the impact of the study drug on your sexual desire?” The second was “Were the benefits of this treatment greater than any side effects?”

Statistical Methods

The trial was powered to detect a small to moderate Cohen's d effect size of 0.45 standard deviations (SDs) in sexual desire change from baseline to 9 weeks (calculated as 9 weeks – baseline) between the placebo arm and either bupropion arm.43 Using a two-sample t-test with a one-sided type I error of 0.05 (overall type I error of 0.1 after a Bonferroni multiplicity correction), 62 patients per arm were required to achieve 80% statistical power. The sample size was inflated by 20% to account for consent withdrawal and patient noncompliance on the FSFI.

Patients were analyzed according to the intent-to-treat principle using all randomly assigned patients. Analyses were conducted between the placebo arm and each bupropion arm separately. Chi-square tests were used to assess between arm differences in categorical variables, and t-tests for continuous variables at the 0.05 significance level. Mixed effects models with maximum likelihood estimation were used to assess longitudinal trends and account for data that are considered missing at random. To account for assessments completed outside of timeframe, the time variable was time from random assignment to PRO completion. Treatment arm, treatment by time interaction, and baseline score were included as covariates. PRO scores (such as PROMIS Fatigue score for FSFI sexual desire), stratification factors, sociodemographic variables (age, race, disease type, partner status, and body mass index), current treatment, time since diagnosis (< 5 years, 5-10 years, and > 1 year), baseline ITS score, and baseline RDAS score were also considered.

RESULTS

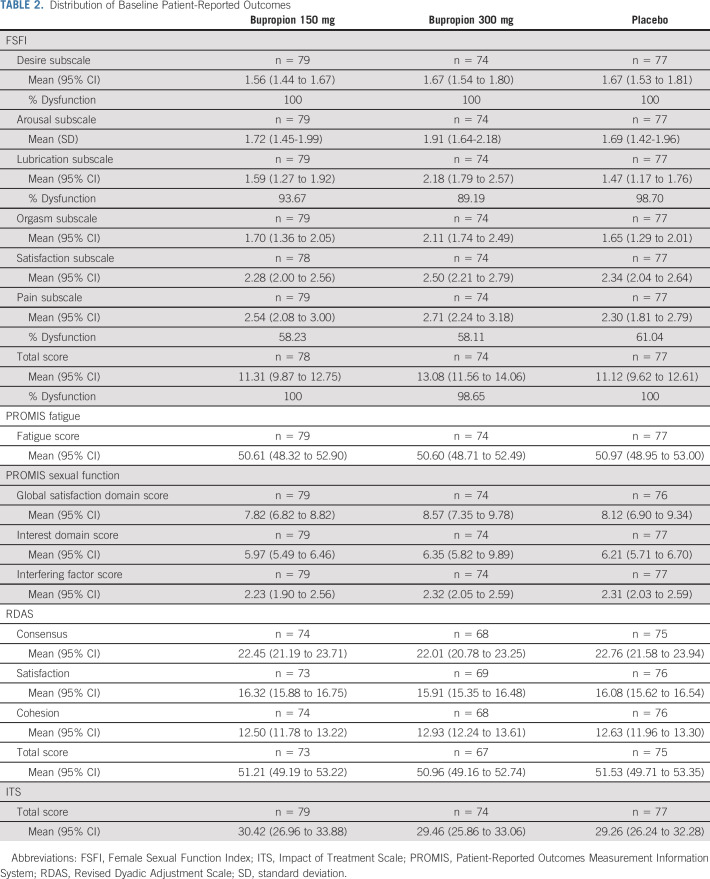

Between May 31, 2017, and April 24, 2020, 238 participants were screened and 230 were randomly assigned from 72 institutions (Fig 1). All randomly assigned patients were eligible with one patient not receiving protocol treatment and 16 patients (five on 150 mg bupropion, seven on 300 mg bupropion, and four on placebo) withdrawing consent. The study closed just short of its target accrual because of drug expiration.

FIG 1.

CONSORT diagram. FSFI, Female Sexual Function Index.

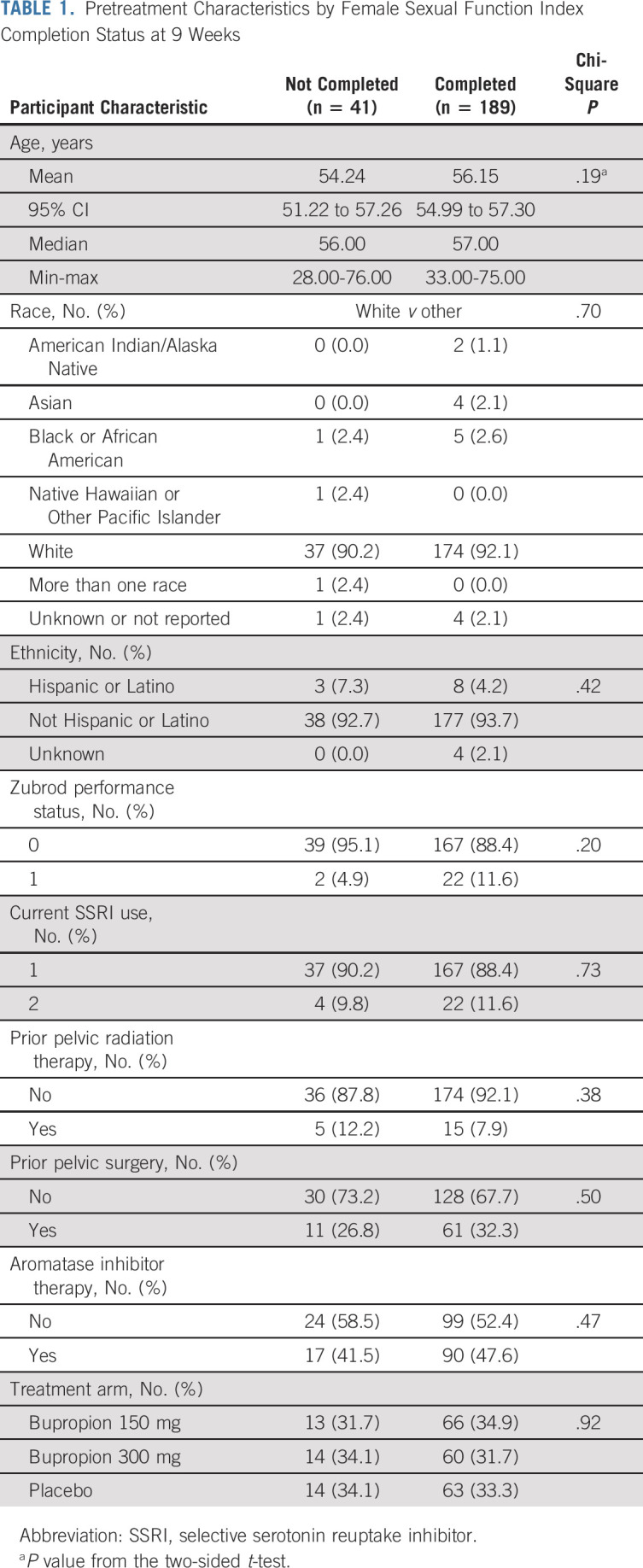

Almost all demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between arms (Data Supplement, online only). There was one significant difference in that patients randomly assigned to placebo were older than those randomly assigned to bupropion (mean age of 58.1 years, 95% CI, 56.3 to 59.9 v 54.6 years, 95% CI, 52.9 to 56.3 for those receiving 150 mg bupropion once daily vs mean age of 54.7 years, 95% CI, 52.6 to 56.8 for those receiving 300 mg bupropion once daily, P = .01). All randomly assigned women completed the FSFI before the start of treatment (Fig 1). At 9 weeks, 195 women (84.8%) completed the FSFI, with 189 (82.2%) being within the time window. Women who completed the FSFI at 9 weeks were similar to women who did not complete the FSFI (Table 1).

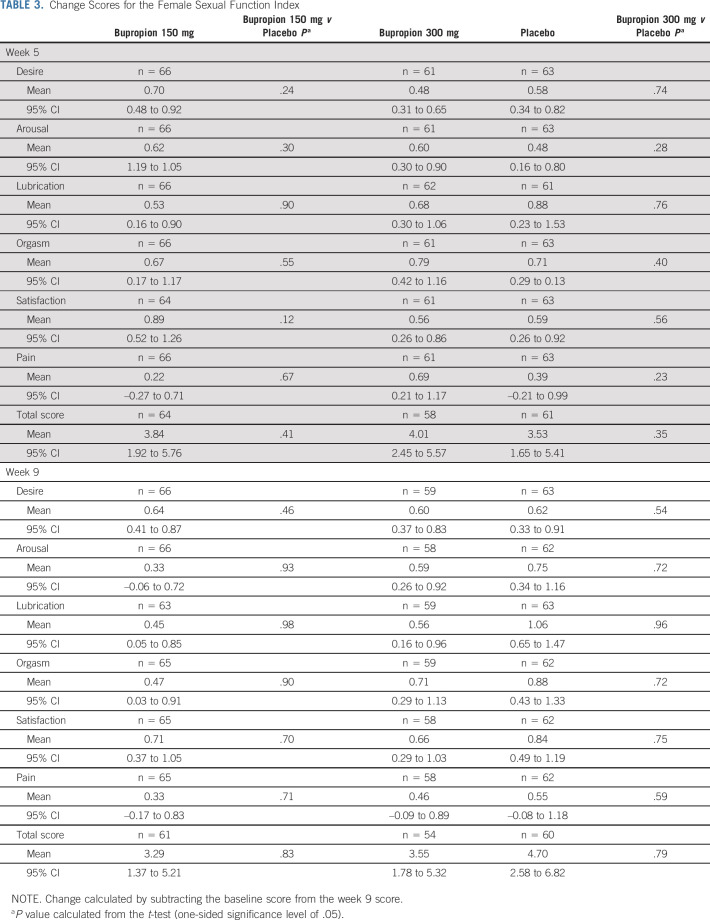

TABLE 1.

Pretreatment Characteristics by Female Sexual Function Index Completion Status at 9 Weeks

There were no significant differences between mean scores on the desire subscale at baseline (150 mg once daily and placebo, –0.11, 95% CI, –0.29 to 0.07; 300 mg once daily and placebo, 0.003, 95% CI, –0.19 to 0.20, Table 2). At baseline, participants in the 300-mg bupropion arm reported significantly higher scores on the lubrication and orgasm subscales of the FSFI and the total score. Mean scores across the three arms for the ITS ranged from 29.26 to 30.42 and for the RDAS from 50.96 to 51.53, indicating relatively lower levels of distress. There were no significant differences between arms at baseline in any of these measures (Table 2). Fatigue scores were just more than 50 in all three groups, which is considered average for the population.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of Baseline Patient-Reported Outcomes

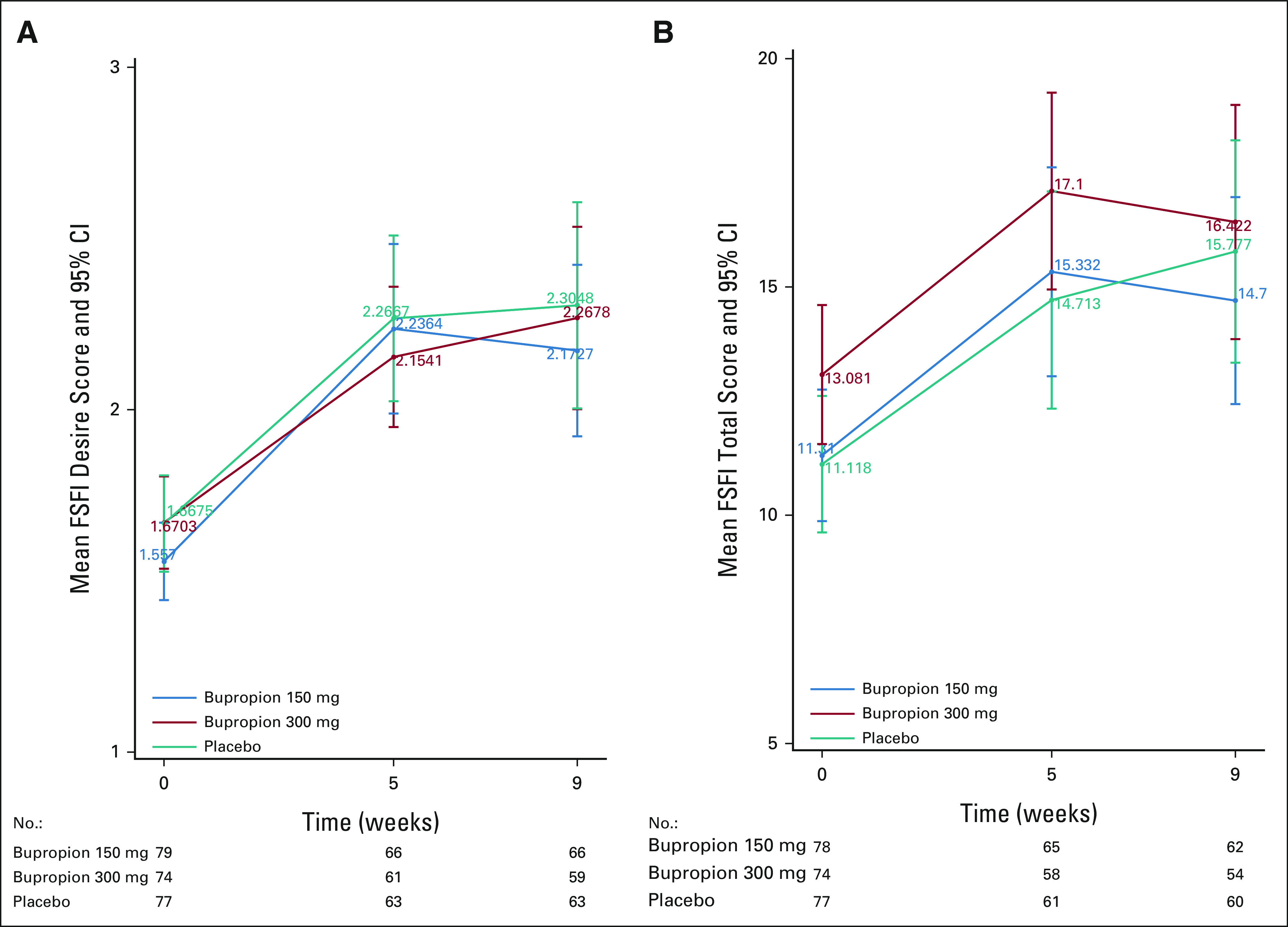

FSFI

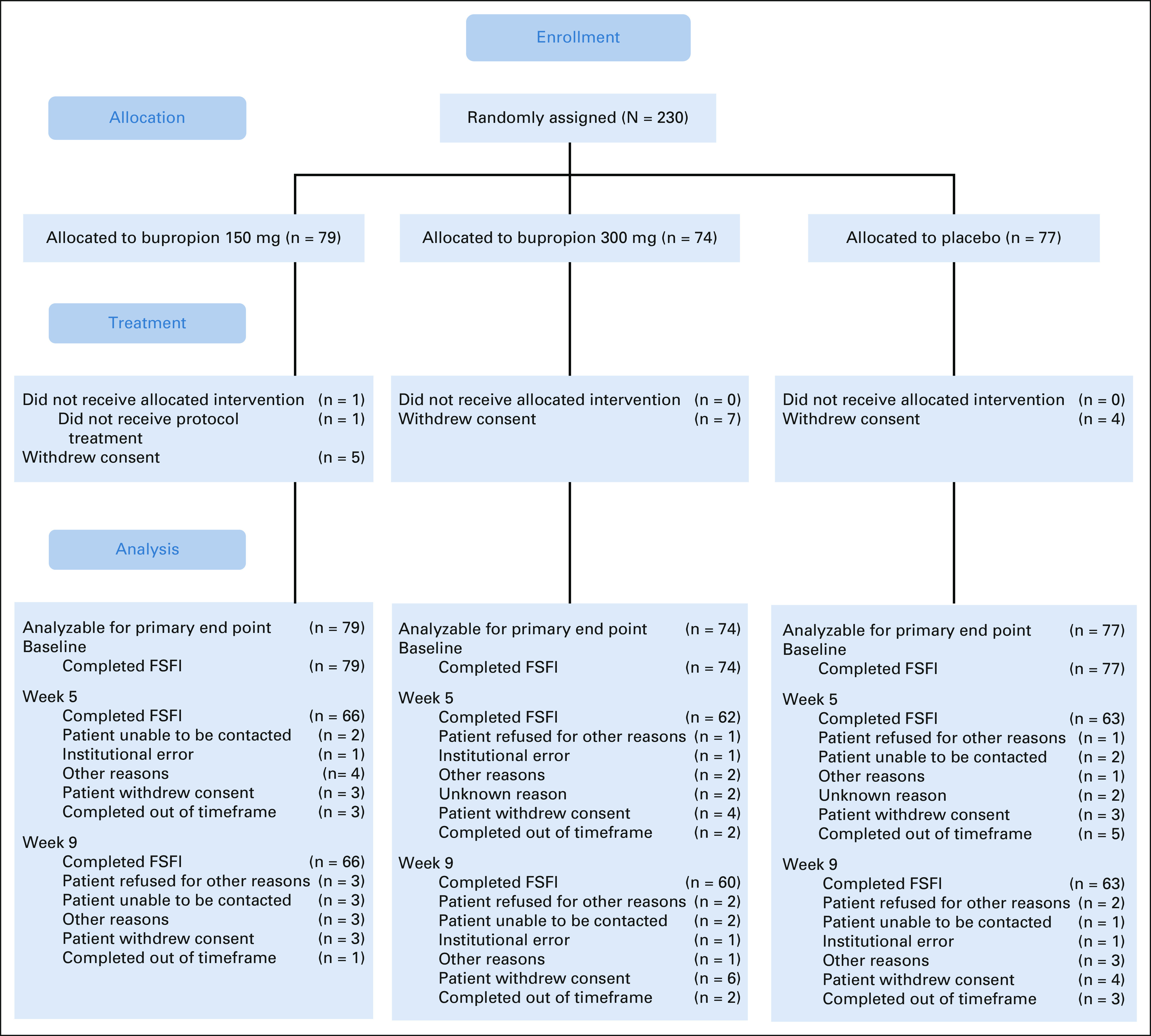

The primary end point of change from baseline to 9 weeks on the desire subscale of the FSFI was not statistically significantly different between any of the three arms (mean between arm change for 150 mg once daily and placebo = 0.02, 95% CI, –0.36 to 0.39, P = .93 and mean between arm change for 300 mg once daily and placebo = –0.02, 95% CI, –0.40 to 0.36, P = .92; Table 3). The effect size between the 150-mg arm and placebo was 0.009 SD and between the 300-mg arm and placebo was 0.01 SD. Similarly, none of the subscales or total score of the FSFI demonstrated a significant difference between arms at either 5 or 9 weeks or significant improvement longitudinally (Table 3, Data Supplement). At 9 weeks, mean scores and 95% CI on the desire subscale of the FSFI were 2.17 (1.92 to 2.42), 2.27 (2.00 to 2.53), and 2.30 (2.00 to 2.61) for the 150-mg, 300-mg, and placebo group, respectively. Total FSFI and subscale scores at weeks 5 and 9 are reported in Figure 2 and the Data Supplement.

TABLE 3.

Change Scores for the Female Sexual Function Index

FIG 2.

(A) FSFI mean desire score over time (higher is better). (B) FSFI mean total score over time (higher is better). FSFI, Female Sexual Function Index.

Toxicity

There were no grade 4 or 5 AEs related to treatment. In the 150-mg bupropion arm, two patients (2.6%) experienced a grade 3 AE (insomnia and headache) and one patient in each of the 300-mg bupropion arm (1.4%) and placebo arm (1.3%) experienced a grade 3 AE related to protocol treatment (hypertension and headache, respectively).

There were few statistically significant differences in PRO-CTCAE between arms. At 7 weeks, with the target dose, more participants in the 300-mg bupropion arm reported headache interference with usual activities compared with the placebo (29.1% v 10.3%, respectively, P = .01; Data Supplement). Also, at 7 weeks, participants in the placebo arm reported more interference from a decreased appetite and insomnia than the 150-mg group (8.6% v 0.0%, respectively, P = .02 for decreased appetite; 37.9% v 20.0%, respectively, P = .03 for insomnia). At 9 weeks, mild to severe dry mouth and insomnia were significantly higher in the placebo arm compared with the 150-mg arm (44.6% v 25%, respectively, P = .03 for dry mouth; 64.3% v 42.1%, respectively, P = .02 for insomnia; Data Supplement).

Patient-Reported Outcomes

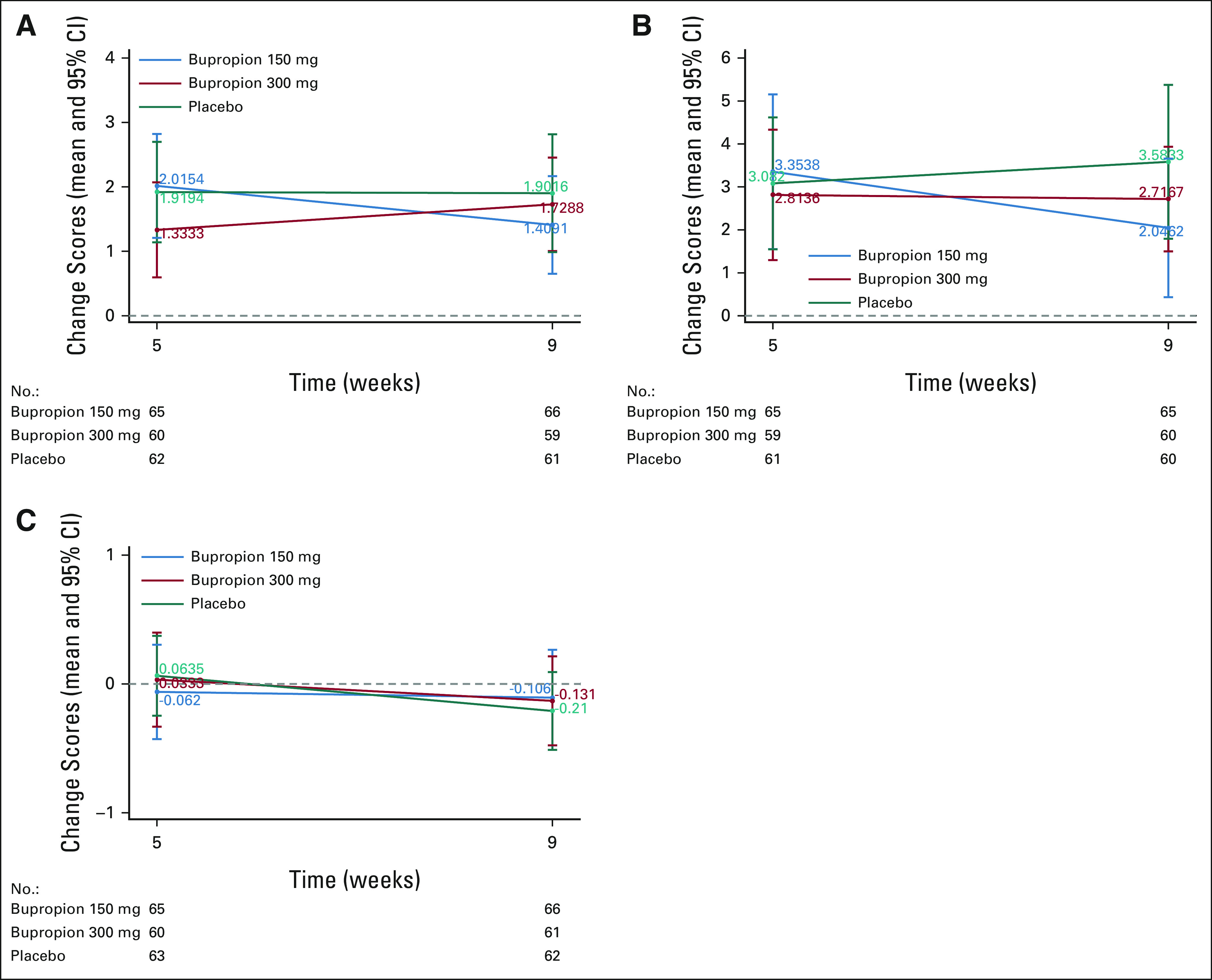

Changes at 9 weeks in the PROMIS sexual interest, global sexual satisfaction, and fatigue interference with sexual function were not significantly different between the placebo and each bupropion arm (Fig 3).

FIG 3.

(A) PROMIS sexual interest mean change scores at 5 and 9 weeks (higher is better). (B) PROMIS global sexual satisfaction mean change scores at 5 and 9 weeks (higher is better). (C) Fatigue mean change score at 5 and 9 weeks (negative change scores indicate improved fatigue).

For satisfaction and perception of risk versus benefit, there were no significant differences between treatment arms (Data Supplement). About 25% of the participants reported satisfaction with the treatment on their sexual desire, whereas 41% reported benefits that were greater than any side effects across all three arms.

DISCUSSION

Despite the clinical use of bupropion to improve sexual desire in reversing negative effects from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and the promising preliminary data in the cancer survivorship literature, the results of this study do not support the use of bupropion for the improvement of sexual desire. All participants improved less than one point on the desire subscale, and importantly, all desire scores remained under the cutoff value for dysfunction on the FSFI.34,35 This lack of benefit was consistent on other secondary measures of sexual interest and satisfaction.

Given the overlapping mechanisms of dopaminergic activity between bupropion and an already FDA-approved drug for HSDD, flibanserin, the insignificant results of this study were surprising. The study of flibanserin, called Plumeria,44 included postmenopausal women with HSDD, so this study population also had low estrogen concentrations. At both 8 and 16 weeks, 100 mg of flibanserin once daily appears to have produced changes in the desire subscale of the FSFI of 0.6, which is what bupropion produced in this study. The placebo response of a 0.4 change in the desire subscale in the Plumeria study was lower than our placebo response. It is interesting that the flibanserin effect on the desire subscale was higher in populations of premenopausal women with HSDD.22,23 This may speak to different mechanisms and/or different treatment needs in women who are more estrogen depleted.

A similar phenomenon was seen in the studies evaluating testosterone for libido. In premenopausal and age-related postmenopausal noncancer populations, transdermal testosterone was perceived by women as being beneficial. In cancer survivors45 and in a subpopulation of postmenopausal women who did not receive estrogen supplementation and who had had a surgical menopause,46 transdermal testosterone was not helpful in improving libido.

Bupropion seems to have been well tolerated, with a majority of the expected side effects being rather equally distributed across all three arms, including placebo. On the basis of the PRO-CTCAE, only headache interference was statistically significantly worse in the 300-mg arm compared with placebo.

At baseline, all subscale scores and total score on the FSFI were well below the established cutoffs indicating sexual dysfunction.34 In fact, the desire subscale scores and total score on the FSFI were lower at baseline in our study than those reported in the flibanserin study with postmenopausal women with HSDD.44

All scores on the FSFI improved over the course of the study in all three arms, providing rationale for the importance of a well-designed control arm in sexual health research. Despite the allowance of treatment for vaginal dryness on this trial, the mean scores at baseline and out to 9 weeks were in the dysfunction range for lubrication and pain.44 Perhaps future studies for libido should require and/or include treatment for vulvovaginal symptoms.

It is important to note that at baseline, the scores on the measures for relationship satisfaction and body image stress indicated that this population was not distressed on these two variables. The cutoff on the RDAS for relationship distress is 47 and lower, whereas the midpoint for body image stress is 32.5, with lower numbers indicating less distress.

Limitations of this trial included that our population was mostly White and non-Hispanic. Strengths included a design using a matching placebo, a double-blind random assignment process, and a well-validated measure of sexual desire. This was also a multisite trial with 72 institutions, mostly community cancer centers, accruing at least one participant.

In conclusion, it is clear from the results of this study that sexual function remains an unmet need in female cancer survivors. More research is needed concerning the underlying mechanisms for loss of sexual desire in cancer survivors, so effective treatments can be developed and evaluated.

Debra L. Barton

Research Funding: Merck

Stephanie L. Pugh

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst), Millennium (Inst)

Patricia A. Ganz

Leadership: Intrinsic LifeSciences (I)

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Xenon Pharma (I), Intrinsic LifeSciences (I), Teva, Novartis, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Abbott Laboratories

Consulting or Advisory Role: InformedDNA, Vifor Pharma (I), Ambys Medicines (I), Global Blood Therapeutics (I), GlaxoSmithKline (I), Ionis Pharmaceuticals (I), Protagonist Therapeutics (I), Akebia Therapeutics (I), Regeneron (I), Sierra Oncology (I), Rockwell Medical Technologies Inc (I), Astellas Pharma (I), Gossamer Bio (I), American Regent (I), Disc Medicine (I), Blue Note Therapeutics (I), Grail (I)

Research Funding: Blue Note Therapeutics (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Related to iron metabolism and the anemia of chronic disease, UpToDate royalties for section editor on survivorship

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Intrinsic LifeSciences (I)

Steven C. Plaxe

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Pfizer, Merck, Zimmer Biomet, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen

Research Funding: Endocyte, Incyte, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Janssen Oncology, BIND Therapeutics, PharmaMar, AstraZeneca, Kevelt, Millennium, Tesaro

Bridget F. Koontz

Employment: GenesisCare

Leadership: GenesisCare

Consulting or Advisory Role: Blue Earth Diagnostics, Myovant Sciences, Rythera Therapeutics

Research Funding: Janssen, Merck, Blue Earth Diagnostics

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Demos Publishing

Matthew L. Hill

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: AstraZeneca, Newlink Genetics, Kazia Therapeutics, Leap Therapeutics, OncoSec, MEI Pharma, PLx Pharma, Radius Health, Crispr Therapeutics, Cassava Sciences

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/820072

Carolyn Y. Muller

Research Funding: AstraZeneca, Genmab, VBL Therapeutics, Roche/Genentech, TapImmune Inc, Linnaeus Therapeutics, Agenus, Incyte, Merck

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Have a pending patent on the cancer use for R-ketorolac—not yet its own new drug

Other Relationship: NCI, Department of Defense

Lisa A. Kachnic

Consulting or Advisory Role: New B Innovation

Research Funding: Varian Medical Systems

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: UpToDate

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

See accompanying editorial on page 317

SUPPORT

Supported by grant no. UG1CA189867 (NCORP) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF).

CLINICAL TRIAL INFORMATION

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Debra L. Barton, Stephanie L. Pugh, Patricia A. Ganz, Bridget F. Koontz, Natalya Greyz-Yusupov, Lisa A. Kachnic

Financial support: Sobia Nabeel

Administrative support: Patricia A. Ganz, Sobia Nabeel

Provision of study materials or patients: Kendrith M. Rowland Jr, Ernie P. Balcueva, Sobia Nabeel, Matthew L. Hill, Carolyn Y. Muller

Collection and assembly of data: Stephanie L. Pugh, Steven C. Plaxe, Jeanne Carter, Natalya Greyz-Yusupov, Seth J. Page, Kendrith M. Rowland Jr, Sobia Nabeel, Jack B. Basil, Matthew L. Hill, Carolyn Y. Muller, Maria C. Bell, Snehal Deshmukh

Data analysis and interpretation: Debra L. Barton, Stephanie L. Pugh, Patricia A. Ganz, Steven C. Plaxe, Bridget F. Koontz, Jeanne Carter, Seth J. Page, Kendrith M. Rowland Jr, Ernie P. Balcueva, Sobia Nabeel, Maria C. Bell, Snehal Deshmukh

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Randomized Controlled Phase II Evaluation of Two Dose Levels of Bupropion Versus Placebo for Sexual Desire in Female Cancer Survivors: NRG-CC004

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Debra L. Barton

Research Funding: Merck

Stephanie L. Pugh

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst), Millennium (Inst)

Patricia A. Ganz

Leadership: Intrinsic LifeSciences (I)

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Xenon Pharma (I), Intrinsic LifeSciences (I), Teva, Novartis, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Abbott Laboratories

Consulting or Advisory Role: InformedDNA, Vifor Pharma (I), Ambys Medicines (I), Global Blood Therapeutics (I), GlaxoSmithKline (I), Ionis Pharmaceuticals (I), Protagonist Therapeutics (I), Akebia Therapeutics (I), Regeneron (I), Sierra Oncology (I), Rockwell Medical Technologies Inc (I), Astellas Pharma (I), Gossamer Bio (I), American Regent (I), Disc Medicine (I), Blue Note Therapeutics (I), Grail (I)

Research Funding: Blue Note Therapeutics (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Related to iron metabolism and the anemia of chronic disease, UpToDate royalties for section editor on survivorship

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Intrinsic LifeSciences (I)

Steven C. Plaxe

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Pfizer, Merck, Zimmer Biomet, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen

Research Funding: Endocyte, Incyte, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Janssen Oncology, BIND Therapeutics, PharmaMar, AstraZeneca, Kevelt, Millennium, Tesaro

Bridget F. Koontz

Employment: GenesisCare

Leadership: GenesisCare

Consulting or Advisory Role: Blue Earth Diagnostics, Myovant Sciences, Rythera Therapeutics

Research Funding: Janssen, Merck, Blue Earth Diagnostics

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Demos Publishing

Matthew L. Hill

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: AstraZeneca, Newlink Genetics, Kazia Therapeutics, Leap Therapeutics, OncoSec, MEI Pharma, PLx Pharma, Radius Health, Crispr Therapeutics, Cassava Sciences

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/820072

Carolyn Y. Muller

Research Funding: AstraZeneca, Genmab, VBL Therapeutics, Roche/Genentech, TapImmune Inc, Linnaeus Therapeutics, Agenus, Incyte, Merck

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Have a pending patent on the cancer use for R-ketorolac—not yet its own new drug

Other Relationship: NCI, Department of Defense

Lisa A. Kachnic

Consulting or Advisory Role: New B Innovation

Research Funding: Varian Medical Systems

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: UpToDate

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society : Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures 2019-2021. Atlanta, GA, American Cancer Society, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR, et al. : Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 17:2371-2380, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmack Taylor CL, Basen-Engquist K, Shinn EH, et al. : Predictors of sexual functioning in ovarian cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 22:881-889, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whicker M, Black J, Altwerger G, et al. : Management of sexuality, intimacy, and menopause symptoms in patients with ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 217:395-403, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holloway V, Wylie K: Sex drive and sexual desire. Curr Opin Psychiatry 28:424-429, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simons JS, Carey MP: Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions: Results from a decade of research. Arch Sex Behav 30:177-219, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC: Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA 281:537-544, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorfman CS, Arthur SS, Kimmick GG, et al. : Partner status moderates the relationships between sexual problems and self-efficacy for managing sexual problems and psychosocial quality-of-life for postmenopausal breast cancer survivors taking adjuvant endocrine therapy. Menopause 26:823-832, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayer S, Iborra S, Grimm D, et al. : Sexual activity and quality of life in patients after treatment for breast and ovarian cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet 299:191-201, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oberguggenberger A, Martini C, Huber N, et al. : Self-reported sexual health: Breast cancer survivors compared to women from the general population—An observational study. BMC Cancer 17:599, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avis NE, Johnson A, Canzona MR, et al. : Sexual functioning among early post-treatment breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 26:2605-2613, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbera L, Zwaal C, Elterman D, et al. : Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer. Curr Oncol 24:192-200, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schover LR: Sexual quality of life in men and women after cancer. Climacteric 22:553-557, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnow BA, Millheiser L, Garrett A, et al. : Women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder compared to normal females: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroscience 158:484-502, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bianchi-Demicheli F, Cojan Y, Waber L, et al. : Neural bases of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women: An event-related FMRI study. J Sex Med 8:2546-2559, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dantzer R, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A, et al. : The neuroimmune basis of fatigue. Trends Neurosci 37:39-46, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felger JC, Miller AH: Cytokine effects on the basal ganglia and dopamine function: The subcortical source of inflammatory malaise. Front Neuroendocrinol 33:315-327, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hull EM, Lorrain DS, Du J, et al. : Hormone-neurotransmitter interactions in the control of sexual behavior. Behav Brain Res 105:105-116, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Versace F, Engelmann JM, Jackson EF, et al. : Brain responses to erotic and other emotional stimuli in breast cancer survivors with and without distress about low sexual desire: A preliminary fMRI study. Brain Imaging Behav 7:533-542, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kingsberg SA, Clayton AH, Pfaus JG: The female sexual response: Current models, neurobiological underpinnings and agents currently approved or under investigation for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. CNS Drugs 29:915-933, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sprout Pharmaceuticals : Flibanserin [package insert]. Raleigh, NC, Sprout Pharmaceuticals, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derogatis LR, Komer L, Katz M, et al. : Treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women: Efficacy of flibanserin in the VIOLET study. J Sex Med 9:1074-1085, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz M, DeRogatis LR, Ackerman R, et al. : Efficacy of flibanserin in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Results from the BEGONIA trial. J Sex Med 10:1807-1815, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorp J, Simon J, Dattani D, et al. : Treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women: Efficacy of flibanserin in the DAISY study. J Sex Med 9:793-804, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.GlaxoSmithKline : Wellbutrin XL® [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC, GlaxoSmithKline, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomson Healthcare : Micromedex Healthcare Series. Greenwood Village, CO, Thomson Healthcare, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clayton AH, Croft HA, Horrigan JP, et al. : Bupropion extended release compared with escitalopram: Effects on sexual functioning and antidepressant efficacy in 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychiatry 67:736-746, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Croft H, Settle E Jr, Houser T, et al. : A placebo-controlled comparison of the antidepressant efficacy and effects on sexual functioning of sustained-release bupropion and sertraline. Clin Ther 21:643-658, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gitlin MJ, Suri R, Altshuler L, et al. : Bupropion-sustained release as a treatment for SSRI-induced sexual side effects. J Sex Marital Ther 28:131-138, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathias C, Cardeal Mendes CM, Ponde de Sena E, et al. : An open-label, fixed-dose study of bupropion effect on sexual function scores in women treated for breast cancer. Ann Oncol 17:1792-1796, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moss EL, Simpson JS, Pelletier G, et al. : An open-label study of the effects of bupropion SR on fatigue, depression and quality of life of mixed-site cancer patients and their partners. Psychooncology 15:259-267, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safarinejad MR: Reversal of SSRI-induced female sexual dysfunction by adjunctive bupropion in menstruating women: A double-blind, placebo-controlled and randomized study. J Psychopharmacol 25:370-378, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Segraves RT, Clayton A, Croft H, et al. : Bupropion sustained release for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women. J Clin Psychopharmacol 24:339-342, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meston CM, Freihart BK, Handy AB, et al. : Scoring and interpretation of the FSFI: What can be learned from 20 years of use? J Sex Med 17:17-25, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R: The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): Cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther 31:1-20, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baser RE, Li Y, Carter J: Psychometric validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in cancer survivors. Cancer 118:4606-4618, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carpenter KM, Andersen BL, Fowler JM, et al. : Sexual self schema as a moderator of sexual and psychological outcomes for gynecologic cancer survivors. Arch Sex Behav 38:828-841, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flynn KE, Lin L, Cyranowski JM, et al. : Development of the NIH PROMIS® sexual function and satisfaction measures in patients with cancer. J Sex Med 10:43-52, 2013. (suppl 1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. : The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol 63:1179-1194, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frierson GM, Thiel DL, Andersen BL: Body change stress for women with breast cancer: The breast-impact of treatment scale. Ann Behav Med 32:77-81, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Crespi CM, et al. : Addressing intimacy and partner communication after breast cancer: A randomized controlled group intervention. Breast Cancer Res Treat 118:99-111, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Busby DM, Christensen C, Crane DR, et al. : A revision of the dyadic adjustment scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples—Construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales. J Marital Fam Ther 21:289-308, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Portman DJ, Brown L, Yuan J, et al. : Flibanserin in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Results of the PLUMERIA study. J Sex Med 14:834-842, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barton DL, Wender DB, Sloan JA, et al. : Randomized controlled trial to evaluate transdermal testosterone in female cancer survivors with decreased libido; North Central Cancer Treatment Group protocol N02C3. J Natl Cancer Inst 99:672-679, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis SR, Moreau M, Kroll R, et al. : Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen. N Engl J Med 359:2005-2017, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]