Abstract

Background

The global incidence and mortality rates of liver cancer, which is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, are increasing. However, information on its epidemiology and clinical prognosis is limited. This study aimed to characterize the epidemiology and prognostic factors of secondary liver cancer to aid in the pretreatment evaluation of the disease.

Methods

Patients diagnosed with secondary liver cancer between 2010 and 2014 in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database were retrospectively included. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Multivariate Cox regression analysis were performed to screen for significant factors associated with secondary liver cancer.

Results

A total of 85,738 secondary liver cancer patients were identified; in this population, the first primary site was the lung (25.9%), followed by the colorectum, pancreas, stomach, breast, and cecum. Patients with primary tumors of the colorectum, cecum and breast had longer median survival time. Advanced age, male gender, black race, poor differentiation or lack of differentiation, regional lymph node metastases, and presence of distant metastasis were associated with poor prognosis.

Conclusions

In this study, novel findings on the role of the primary site and synchronous distant metastasis to specific organs in patients with secondary liver cancer were described. These findings have significant implications in clinical diagnosis and treatment, and provide a better understanding of secondary liver cancer in the general population.

Keywords: Secondary liver cancer; epidemiology; prognosis; primary site; Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)

Introduction

Liver cancer is the fifth and ninth most common cancer in male and female, respectively (1). It is the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide (1,2). In 2012, 782,500 newly diagnosed liver cancer cases and 745,500 deaths due to the same were estimated globally (2,3). Moreover, secondary liver cancer is more common than primary liver cancer (4-6).

The liver is one of the most common sites for organ-specific metastasis (7), which is mainly attributable to the organ-specific circulation pattern and distinct anatomy of microvessels (8). The liver has a unique dual blood supply system from both the portal vein and the hepatic artery, which increases the possibility of metastatic deposition. In addition, the sinusoidal hepatic endothelial layer is characterized by an incomplete covering of the microvessel structures (9); consequently, the extracellular matrix components are directly accessible to the circulating cells (9,10).

Although the global incidence and mortality rates of liver cancer are increasing, imposing a huge burden on the health care system (3), information regarding the epidemiology and clinical prognosis of secondary liver cancer is still limited. Using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, we conducted a population-based analysis to comprehensively identify the epidemiological characters and prognostic factors of secondary liver cancer, to potentially help clinicians make better clinical decisions during pretreatment evaluation. We present the following article in accordance with the STORBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr-20-3319).

Methods

Data source

As the SEER database is publicly available, and the data used in this study did not include specific patient identifiers, the study did not require a review by the ethics committee. The SEER program is a premier source of cancer statistics in the United States and collects data from 18 population-based central cancer registries while covering 27–30% of the US population (11). SEER*Stat 8.3.5 (National Cancer Institute, MD, USA) software was used to extract the data. We identified 85,738 patients, whose liver metastases were synchronous to the primary tumor as secondary liver cancer patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2014. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Variables

Covariates included demographic variables (age at diagnosis, gender, race) and diagnostic information (primary site, tumor size, grade, lymph nodes stage, and synchronous additional distant metastasis to specific organs). The outcome measures were overall survival (OS, time from the diagnosis of secondary liver cancer to by any cause) and cancer-specific survival (CSS, time from the diagnosis of secondary liver cancer to death by cancer). We used the term “unknown” to represent missing data and treated it as an independent variable during analysis.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank test were used to estimate and compare the outcomes between different primary sites. Multivariate Cox regression models were conducted after adjusting for various covariates to assess the prognostic factors associated with OS and CSS. Hazard ratio (HR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was used to show the effect of different variables on OS and CSS (12). All tests were two-sided, and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

A total of 85,738 patients with secondary liver cancer were included in our study. As shown in Table 1, majority of the secondary liver cancers originated from the digestive system (56.9%), and the six most common primary sites were the lung (25.9%), colorectum (21.4%), pancreas (19.6%), stomach (4.6%), breast (4.4%) and cecum (4.1%). When stratified by race, the first primary site was the lung for White and the colorectum for Black or Others patients. Interestingly, there was a significant number of male cases whose primary site was esophagus or stomach (male: female=10.5:3.7).

Table 1. Relative frequencies of secondary liver cancer patients by primary site, gender, and race.

| Primary site | Total | Gender | Race | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | White | Black | Others | Unknown | |||||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Esophagus | 2,296 | 2.7 | 1,976 | 4.4 | 320 | 0.8 | 2,023 | 3.0 | 182 | 1.6 | 84 | 1.3 | 7 | 2.7 | ||

| Stomach | 3,915 | 4.6 | 2,758 | 6.1 | 1,157 | 2.9 | 2,797 | 4.2 | 626 | 5.4 | 472 | 7.1 | 20 | 7.6 | ||

| Small intestine | 1,249 | 1.5 | 663 | 1.5 | 586 | 1.4 | 991 | 1.5 | 204 | 1.7 | 53 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.4 | ||

| Cecum | 3,542 | 4.1 | 1,710 | 3.8 | 1,832 | 4.5 | 2,696 | 4.0 | 651 | 5.6 | 186 | 2.8 | 9 | 3.4 | ||

| Colorectum | 18,334 | 21.4 | 10,460 | 23.2 | 7,874 | 19.4 | 13,755 | 20.5 | 2,770 | 23.7 | 1,754 | 26.4 | 55 | 21.0 | ||

| Gallbladder/Biliary tract | 2,603 | 3.0 | 1,089 | 2.4 | 1,514 | 3.7 | 1,976 | 2.9 | 332 | 2.8 | 287 | 4.3 | 8 | 3.1 | ||

| Pancreas | 16,841 | 19.6 | 9,139 | 20.2 | 7,702 | 19.0 | 13,186 | 19.6 | 2,285 | 19.6 | 1,304 | 19.6 | 66 | 25.2 | ||

| Lung | 22,214 | 25.9 | 12,234 | 27.1 | 9,980 | 24.6 | 18,413 | 27.4 | 2,376 | 20.3 | 1,389 | 20.9 | 36 | 13.7 | ||

| Breast | 3,745 | 4.4 | 22 | 0.0 | 3,723 | 9.2 | 2,757 | 4.1 | 679 | 5.8 | 294 | 4.4 | 15 | 5.7 | ||

| Urinary system | 2,609 | 3.0 | 1,668 | 3.7 | 941 | 2.3 | 2,101 | 3.1 | 322 | 2.8 | 180 | 2.7 | 6 | 2.3 | ||

| Reproductive system | 3,603 | 4.2 | 809 | 1.8 | 2,794 | 6.9 | 2,700 | 4.0 | 613 | 5.2 | 276 | 4.2 | 14 | 5.3 | ||

| Others | 4,787 | 5.6 | 2,643 | 5.9 | 2,144 | 5.3 | 3,753 | 5.6 | 643 | 5.5 | 366 | 5.5 | 25 | 9.5 | ||

| Total | 85,738 | 100 | 45,171 | 100 | 40,567 | 100 | 67,148 | 100 | 11,683 | 100 | 6,645 | 100 | 262 | 100 | ||

Considering that unspecific or unknown primary sites, as well as the shortage of cases could contribute as potential confounding factors, we only showed patient characteristics for those who had secondary liver cancer from the top six primary sites described above (Table 2). For patients with breast as the primary site, the proportion below the age of 40 was high. We also observed that patients, whose primary sites were the lung or breast, were more likely to have synchronous distant metastasis, especially bone metastasis.

Table 2. Characteristics of secondary liver cancer patients from the six most common primary sites.

| Characteristic | Total, No. (%) | Stomach, No. (%) | Cecum, No. (%) | Colorectum, No. (%) | Pancreas, No. (%) | Lung, No. (%) | Breast, No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | 68,591 (100.0) | 3,915 (100.0) | 3,542 (100.0) | 1,8334 (100.0) | 1,6841 (100.0) | 22,214 (100.0) | 3,745 (100.0) |

| Age at diagnosis, years | |||||||

| <40 | 1,654 (2.4) | 128 (3.3) | 62 (1.8) | 768 (4.2) | 219 (1.3) | 140 (0.6) | 337 (9.0) |

| 40–59 | 19,707 (28.7) | 1,127 (28.8) | 1,005 (28.4) | 6,620 (36.1) | 4,209 (25.0) | 5,120 (23.0) | 1,626 (43.4) |

| 60–79 | 36,284 (52.9) | 2,022 (51.6) | 1,736 (49.0) | 8,201 (44.7) | 9,350 (55.5) | 13,551 (61.0) | 1,424 (38.0) |

| ≥80 | 10,946 (16.0) | 638 (16.3) | 739 (20.9) | 2,745 (15.0) | 3,063 (18.2) | 3,403 (15.3) | 358 (9.6) |

| Tumor size, cm | |||||||

| <2 | 3,361 (4.9) | 101 (2.6) | 89 (2.5) | 471 (2.6) | 650 (3.9) | 1,629 (7.3) | 421 (11.2) |

| 2–4 | 21,855 (31.9) | 596 (15.2) | 981 (27.7) | 4,295 (23.4) | 7,751 (46.0) | 6,967 (31.4) | 1,265 (33.8) |

| 5–9 | 19,141 (27.9) | 758 (19.4) | 1,401 (39.6) | 5,740 (31.3) | 4,204 (25.0), | 6,127 (27.6) | 911 (24.3) |

| ≥10 | 2,795 (4.1) | 220 (5.6) | 171 (4.8) | 826 (4.5) | 323 (1.9) | 962 (4.3) | 293 (7.8) |

| Unknown | 21,439 (31.3) | 2,240 (57.2) | 900 (25.4) | 7,002 (38.2) | 3,913 (23.2) | 6,529 (29.4) | 855 (22.8) |

| Grade | |||||||

| Grade I | 1,620 (2.4) | 97 (2.5) | 192 (5.4) | 665 (3.6) | 343 (2.0) | 195 (0.9) | 128 (3.4) |

| Grade II | 14,484 (21.1) | 933 (23.8) | 1,684 (47.5) | 8,847 (48.3) | 1,095 (6.5) | 918 (4.1) | 1,007 (26.9) |

| Grade III | 12,427 (18.1) | 1,814 (46.3) | 687 (19.4) | 2,892 (15.8) | 1,693 (10.1) | 3,748 (16.9) | 1,593 (42.5) |

| Grade IV | 2,023 (2.9) | 75 (1.9) | 159 (4.5) | 501 (2.7) | 146 (0.9) | 1,110 (5.0) | 32 (0.9) |

| Unknown | 38,037 (55.5) | 996 (25.4) | 820 (23.2) | 5,429 (29.6) | 13,564 (80.5) | 16,243 (73.1) | 985 (26.3) |

| N–stage | |||||||

| Node negative | 2,588 (3.8) | 65 (1.7) | 270 (7.6) | 1,710 (9.3) | 228 (1.4) | 167 (0.8) | 148 (4.0) |

| Node positive | 11,671 (17.0) | 248 (6.3) | 1,821 (51.4) | 5,938 (32.4) | 507 (3.0) | 2,010 (9.0) | 1,147 (30.6) |

| Unknown | 54,332 (79.2) | 3,602 (92.0) | 1,451 (41.0) | 10,686 (58.3) | 16,106 (95.6) | 20,037 (90.2) | 2,450 (65.4) |

| Additional metastasis | |||||||

| None | 37,828 (55.2) | 2,756 (70.4) | 2,594 (73.2) | 12,431 (67.8) | 12,273 (72.9) | 6,822 (30.7) | 952 (25.4) |

| Bone | 7,313 (10.7) | 207 (5.3) | 90 (2.5) | 506 (2.8) | 592 (3.5) | 4,792 (21.6) | 1,126 (30.1) |

| Brain | 1,477 (2.2) | 22 (0.6) | 5 (0.1) | 52 (0.3) | 36 (0.2) | 1,329 (6.0) | 33 (0.9) |

| Lung | 9,461 (13.8) | 490 (12.5) | 588 (16.6) | 3,721 (20.3) | 2,272 (13.5) | 2,054 (9.2) | 336 (9.0) |

| Two or Three | 7,574 (11.0) | 156 (4.0) | 101 (2.9) | 546 (3.0) | 442 (2.6) | 5,317 (23.9) | 1,012 (27.0) |

| Unknown | 4,938 (7.2) | 284 (7.3) | 164 (4.6) | 1,078 (5.9) | 1,226 (7.3) | 1,900 (8.6) | 286 (7.6) |

Survival outcomes

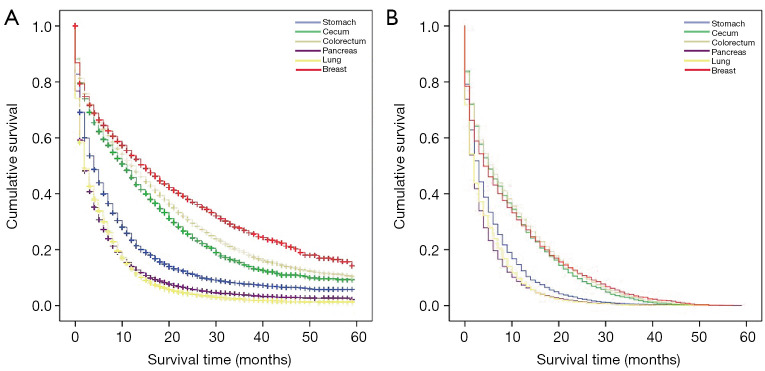

Among the total study population, the median and average OS were 3 months and 7.680±10.467 months, respectively, and that for CSS were 2 months and 5.820±8.015 months, respectively (Table 3). The OS and CSS Kaplan–Meier curves showed significant differences in survival outcomes according to primary sites (Figure 1). The median CSS of patients with the colorectum as the primary site was 6 months, which was greater than that of patients with other primary sites. Patients whose primary sites were the lung and pancreas had the worst median CSS of 2 months (Table 3).

Table 3. Survival time of secondary liver cancer patients with the first six primary sites.

| Primary site | No. (%) | Overall survival | Cancer-specific survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Average | SE | Median | Average | SE | |||

| Stomach | 3,915 (5.7) | 3 | 6.95 | 9.529 | 3 | 5.36 | 6.85 | |

| Cecum | 3,542 (5.2) | 7 | 11.2 | 12.256 | 5 | 9.14 | 10.087 | |

| Colorectum | 18,334 (26.7) | 8 | 12.28 | 12.954 | 6 | 9.69 | 10.676 | |

| Pancreas | 16,841 (24.6) | 2 | 4.79 | 7.39 | 2 | 3.91 | 5.627 | |

| Lung | 22,214 (32.4) | 2 | 4.7 | 6.763 | 2 | 4.18 | 5.676 | |

| Breast | 3,745 (5.5) | 8 | 13.23 | 13.948 | 4 | 9.24 | 11.22 | |

| Total | 68,591 (100.0) | 3 | 7.68 | 10.467 | 2 | 5.82 | 8.015 | |

Figure 1.

Comparison of survival in secondary liver cancer patients according to specific primary sites. Kaplan-Meier analysis for overall survival (A) and cancer-specific survival (B).

Multivariate prognostic factors

Results of the multivariate analysis indicated that advanced age, male gender, black race, poor differentiation or lack of differentiation, and regional lymph node metastases were associated with poor prognosis (Table 4). Patients with the pancreas, lung or stomach as the primary site had a higher risk of poor outcomes. (Table 4).

Table 4. Multivariate analyses of factors affecting overall survival and cancer-specific survival in secondary liver cancer patients from the six most common primary sites.

| Variable | TOTAL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | Cancer-specific survival | ||||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Primary site | |||||

| Stomach | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Cecum | 0.891 (0.844–0.942) | <0.001 | 0.843 (0.796–0.892) | <0.001 | |

| Colorectum | 0.773 (0.742–0.805) | <0.001 | 0.772 (0.74–0.805) | <0.001 | |

| Pancreas | 1.371 (1.316–1.428) | <0.001 | 1.224 (1.173–1.277) | <0.001 | |

| Lung | 1.221 (1.173–1.272) | <0.001 | 1.087 (1.042–1.134) | <0.001 | |

| Breast | 0.605 (0.571–0.641) | <0.001 | 0.749 (0.706–0.795) | <0.001 | |

| Age at diagnosis, years | |||||

| <40 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| 40–59 | 1.354 (1.265–1.449) | <0.001 | 1.185 (1.105–1.271) | <0.001 | |

| 60–79 | 1.866 (1.744–1.995) | <0.001 | 1.519 (1.418–1.628) | <0.001 | |

| ≥80 | 3.067 (2.862–3.288) | <0.001 | 2.288 (2.13–2.457) | <0.001 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Female | 0.942 (0.926–0.959) | <0.001 | 0.953 (0.936–0.971) | <0.001 | |

| Race | |||||

| White | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Black | 1.105 (1.078–1.133) | <0.001 | 1.064 (1.037–1.091) | <0.001 | |

| Others | 0.879 (0.851–0.908) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.899–0.961) | <0.001 | |

| Tumor size, cm | |||||

| <2 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| 2–4 | 0.998 (0.958–1.04) | 0.924 | 0.998 (0.956–1.042) | 0.943 | |

| 5–9 | 1.11 (1.064–1.157) | <0.001 | 1.093 (1.046–1.141) | <0.001 | |

| ≥10 | 1.191 (1.125–1.261) | <0.001 | 1.18 (1.112–1.252) | <0.001 | |

| Grade | |||||

| Grade I | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Grade II | 1.362 (1.273–1.458) | <0.001 | 1.124 (1.047–1.206) | 0.001 | |

| Grade III | 1.986 (1.856–2.125) | <0.001 | 1.489 (1.388–1.597) | <0.001 | |

| Grade IV | 2.056 (1.897–2.229) | <0.001 | 1.496 (1.376–1.627) | <0.001 | |

| N-stage | |||||

| Node negative | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Node positive | 2.197 (2.072–2.33) | <0.001 | 1.514 (1.424–1.61) | <0.001 | |

| Additional metastasis | |||||

| None | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Bone | 1.164 (1.128–1.2) | <0.001 | 1.096 (1.062–1.131) | <0.001 | |

| Brain | 1.28 (1.209–1.356) | <0.001 | 1.189 (1.121–1.261) | <0.001 | |

| Lung | 1.244 (1.212–1.276) | <0.001 | 1.154 (1.124–1.185) | <0.001 | |

| Two or Three | 1.312 (1.273–1.353) | <0.001 | 1.223 (1.185–1.261) | <0.001 | |

Model adjusted for primary site, age at diagnosis, gender, race, tumor size, grade, N-stage, and additional metastasis.

The number of patients who had synchronous distant metastasis to specific organs was limited; hence, we analyzed this variable in specific cohorts. In the cohort of patients under the first six primary sites, the site specific HR for metastasis were: brain, CSS: 1.189, P<0.001; lung, CSS: 1.154, P<0.001; and bone, CSS: 1.096, P<0.001 (Table 4). In the cohort of patients with colorectum as the primary site, combined with bone metastasis had the worst CSS (HR: 1.402, P<0.001). In the cohort of patients with pancreas as the primary site, combined with brain metastasis had the worst CSS (HR: 1.61, P=0.007). In the cohort of patients with the lung as the primary site, HR for metastasis showed no significant difference (Table 5).

Table 5. Multivariate analyses of factors affecting overall survival and cancer-specific survival in secondary liver cancer patients with the specific primary sites.

| Variable | Primary site | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectum | Pancreas | Lung | |||||||||||||||

| Overall survival | Cancer-specific survival | Overall survival | Cancer-specific survival | Overall survival | Cancer-specific survival | ||||||||||||

| HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | ||||||

| Age at diagnosis, years | |||||||||||||||||

| <40 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||||||||||

| 40–59 | 1.102 (0.994–1.221) |

0.064 | 1.097 (0.987–1.219) |

0.085 | 1.725 (1.446–2.058) |

<0.001 | 1.52 (1.266–1.825) |

<0.001 | 1.543 (1.266–1.882) |

<0.001 | 1.253 (1.021–1.538) |

0.031 | |||||

| 60–79 | 1.702 (1.538–1.883) |

<0.001 | 1.478 (1.332–1.64) |

<0.001 | 2.381 (2–2.836) | <0.001 | 1.947 (1.624–2.334) |

<0.001 | 1.924 (1.58–2.344) |

<0.001 | 1.559 (1.272–1.91) |

<0.001 | |||||

| ≥80 | 3.384 (3.042–3.764) |

<0.001 | 2.473 (2.216–2.759) |

<0.001 | 3.971 (3.324–4.742) |

<0.001 | 3.102 (2.579–3.731) |

<0.001 | 2.735 (2.24–3.34) |

<0.001 | 2.117 (1.723–2.601) |

<0.001 | |||||

| Gender | |||||||||||||||||

| Male | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||||||||||

| Female | 1.024 (0.987–1.061) |

0.202 | 1.037 (0.999–1.077) |

0.058 | 0.966 (0.934–0.998) |

0.038 | 0.955 (0.923–0.988) |

0.008 | 0.871 (0.846–0.896) |

<0.001 | 0.898 (0.872–0.924) |

<0.001 | |||||

| Race | |||||||||||||||||

| White | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||||||||||

| Black | 1.234 (1.175–1.296) |

0.064 | 1.077 (1.023–1.133) |

0.005 | 1.138 (1.085–1.194) |

<0.001 | 1.121 (1.067–1.177) |

<0.001 | 1.01 (0.965–1.057) |

0.656 | 1.017 (0.97–1.067) |

0.473 | |||||

| Others | 0.956 (0.898–1.018) |

<0.001 | 0.962 (0.901–1.027) |

0.246 | 0.976 (0.918–1.038) |

0.437 | 1.007 (0.945–1.072) |

0.838 | 0.745 (0.701–0.792) |

<0.001 | 0.822 (0.772–0.876) |

<0.001 | |||||

| Tumor size, cm | |||||||||||||||||

| <2 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||||||||||

| 2–4 | 0.911 (0.807–1.028) |

0.132 | 0.942 (0.829–1.07) |

0.356 | 1.011 (0.927–1.103) |

0.799 | 0.993 (0.907–1.086) |

0.870 | 1.027 (0.969–1.088) |

0.373 | 1.017 (0.958–1.08) |

0.579 | |||||

| 5–9 | 1.08 (0.959–1.217) |

0.203 | 1.073 (0.947–1.217) |

0.267 | 1.101 (1.006–1.204) |

0.036 | 1.107 (1.009–1.214) |

0.032 | 1.14 (1.074–1.209) |

<0.001 | 1.097 (1.032–1.166) |

0.003 | |||||

| ≥10 | 1.275 (1.108–1.467) |

0.001 | 1.224 (1.057–1.418) |

0.007 | 1.113 (0.961–1.289) |

0.153 | 1.183 (1.017–1.377) |

0.029 | 1.217 (1.118–1.325) |

<0.001 | 1.178 (1.079–1.287) |

<0.001 | |||||

| Grade | |||||||||||||||||

| Grade I | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||||||||||

| Grade II | 1.041 (0.939–1.154) |

0.443 | 1.031 (0.927–1.147) |

0.575 | 2.279 (1.934–2.685) |

<0.001 | 1.551 (1.309–1.838) |

<0.001 | 1.273 (1.064–1.524) |

0.008 | 1.071 (0.889–1.29) |

0.471 | |||||

| Grade III | 1.645 (1.476–1.834) |

<0.001 | 1.459 (1.304–1.633) |

<0.001 | 3.089 (2.636–3.62) |

<0.001 | 1.899 (1.611–2.237) |

<0.001 | 1.703 (1.439–2.015) |

<0.001 | 1.35 (1.133–1.609) |

0.001 | |||||

| Grade IV | 1.926 (1.667–2.226) |

<0.001 | 1.512 (1.3–1.758) |

<0.001 | 3.059 (2.425–3.858) |

<0.001 | 2.026 (1.598–2.568) |

<0.001 | 1.697 (1.423–2.023) |

<0.001 | 1.257 (1.046–1.51) |

0.015 | |||||

| N-stage | |||||||||||||||||

| Node negative | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||||||||||

| Node positive | 1.618 (1.493–1.754) |

<0.001 | 1.189 (1.092–1.294) | <0.001 | 1.225 (1.01–1.486) |

0.039 | 1.169 (0.959–1.425) |

0.122 | 1.134 (0.945–1.359) |

0.176 | 0.977 (0.811–1.178) |

0.808 | |||||

| Additional metastasis | |||||||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||||||||||

| Bone | 1.557 (1.406–1.726) |

<0.001 | 1.402 (1.262–1.557) |

<0.001 | 1.181 (1.08–1.291) |

<0.001 | 1.158 (1.058–1.269) |

0.002 | 1.079 (1.042–1.117) |

<0.001 | 1.055 (1.017–1.094) |

0.004 | |||||

| Brain | 1.795 (1.334–2.416) |

<0.001 | 1.219 (0.899–1.652) |

0.202 | 1.634 (1.161–2.301) |

0.005 | 1.61 (1.137–2.279) |

0.007 | 1.144 (1.077–1.217) |

<0.001 | 1.115 (1.047–1.187) |

0.001 | |||||

| Lung | 1.24 (1.185–1.297) |

<0.001 | 1.117 (1.066–1.17) |

<0.001 | 1.302 (1.241–1.365) |

<0.001 | 1.234 (1.175–1.295) |

<0.001 | 1.134 (1.076–1.194) |

<0.001 | 1.102 (1.044–1.164) |

<0.001 | |||||

| Two or Three | 1.721 (1.562–1.896) |

<0.001 | 1.394 (1.263–1.54) |

<0.001 | 1.503 (1.362–1.658) |

<0.001 | 1.331 (1.202–1.473) |

<0.001 | 1.162 (1.11–1.216) |

<0.001 | 1.153 (1.101–1.208) |

<0.001 | |||||

Discussion

Population-based incidence and survival studies can provide valuable information for clinicians, researchers, and public health officials; these can also guide the direction of future research. In this study, we described the incidence, survival outcomes and prognostic factors of secondary liver cancer. Our findings indicate that the most common primary site was the lung, followed by the colorectum and pancreas, consistent with the findings of previous studies (6,13). However, Bosch et al. (14) established the breast as the most common primary site. This difference can be mainly attributed to the inclusion criteria set for study participants. Lung and pancreatic metastases are commonly synchronous, but breast metastasis tends to be metachronous (15,16). Moreover, the median disease-free interval before clinical liver metastasis for breast cancer patients is 20.2 months (16).

We found that advanced age, male gender, black race, poor differentiation or lack of differentiation, and regional lymph node metastases were associated with worse prognosis; however, the impact of race and tumor size were not obvious. Tumor size is closely correlated with the cancer stage at diagnosis (17). Generally, patients with small tumor size are asymptomatic, and computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography are not performed unless metastatic disease is suspected (5,18). Therefore, we speculate that patients with small tumors included in our study were diagnosed at an early stage due to their more severe clinical manifestations, which weakened the association between tumor size and prognosis. Nevertheless, liver function and other clinical indexes were not available during our study; hence, this speculation must be verified through further research.

Previous studies were mostly based on single-institution experience and focused on one specific primary cancer site; therefore, the survival time of secondary liver cancer patients was rarely described systematically with respect to the primary sites. For example, in secondary liver patients deriving from colorectum who undergo primary tumor resection, the mean survival is approximately 6-9 months (19,20). Another study reported that for secondary liver cancer patients deriving from breast cancer, the median OS was 7 months (21). One epidemiological study on secondary liver cancer patients deriving from adenocarcinoma and small cell lung cancer showed the mean OS was 3 months and 4 months, respectively (22). Owing to the bias caused by the inclusion criteria, number of participants, data sources, and the survival time reported in different studies varies greatly, highlighting the need for the current study to help fill in the gaps. In contrast, this bias was reduced in our study, hence providing more objective and accurate findings. Overall, we performed a horizontal comparison among secondary liver cancer patients from the six most common primary sites, and found that patients whose primary sites were the colorectum, breast, and cecum had longer CSS than those whose primary sites were the stomach, lung, and pancreas.

Interestingly, we found that for secondary liver cancer patients deriving from colorectum, bone metastasis was a poor prognostic factor, as compared to metastases in other organs. Bone metastasis is very rare and the prognosis for colorectal cancer is poor (23-25). Moreover, numerous skeletal-related clinical events may occur in patients with bone metastasis, which decreases the patients’ functionality and quality of life (26,27). Early secondary liver cancer is asymptomatic, whereas bone metastasis is often symptomatic; therefore, bone metastasis could act as a warning signal during disease screening. We also found that for patients deriving from pancreas, brain metastasis was a poor prognostic factor. It is extremely rare in pancreatic cancer and only a few case reports exist for reference (28). In most of the reported cases, the disease had rapidly progressed, and the patients soon died after palliative treatment (28-30). Moreover, patients benefit poorly from surgical resection of brain metastases (30,31).

A current study reported that circulation patterns, extravasation barriers, and survival on arrival are three key determinants of the capacity of particular tumors to seed specific organs (32). Furthermore, the microenvironment, chemokines, and microRNAs are being widely investigated to reveal the molecular mechanisms of metastatic organ tropism (32-35). Based on our findings, we conclude that there may be interactions between synchronous distant metastases and the primary sites in secondary liver cancer, which influence its incidence and prognosis, and this conclusion provides clinical evidence for basic research.

The present study has some potential limitations. First, the SEER database did not include information on synchronous distant metastasis to specific organs until 2010; therefore, the follow-up period was not long enough. Second, we were limited to the information that the SEER database provided; hence, systemic therapy, other metastatic sites, and physical condition of patients that may relate to prognosis were not considered.

Despite these limitations, our study is the most comprehensive population-based analysis for secondary liver cancer. These findings can help oncologists and hepatologists design personalized treatment and appropriate follow-up strategy, and provide a better understanding of secondary liver cancer for the general population.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Xudong Yao for assistance in using the SEER*Stat 8.3.5 software, and the efforts of the National Cancer Institute.

Funding: This study was supported by a Fundamental Research Funds of Wuhan Municipal Health Commission grant to Yan-yan Chen (Grant NO: EX20B01).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STORBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr-20-3319

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr-20-3319). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359-86. 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87-108. 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong MC, Jiang JY, Goggins WB, et al. International incidence and mortality trends of liver cancer: a global profile. Sci Rep 2017;7:45846. 10.1038/srep45846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ananthakrishnan A, Gogineni V, Saeian K. Epidemiology of Primary and Secondary Liver Cancers. Semin Intervent Radiol 2006;23:47-63. 10.1055/s-2006-939841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed I, Lobo DN. Malignant tumours of the liver. Surgery 2009;27:30-7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasper HU, Drebber U, Dries V, et al. Liver Metastases: Incidence and Histogenesis. Z Gastroenterol 2005;43:1149-57. 10.1055/s-2005-858576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen DX, Bos PD, Massagué J. Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:274-84. 10.1038/nrc2622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin K, Gao W, Lu Y, et al. Mechanisms regulating colorectal cancer cell metastasis into liver (Review). Oncol Lett 2012;3:11-5. 10.3892/ol.2011.432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahn E, Wick G, Pencev D, et al. Distribution of basement membrane proteins in normal and fibrotic human liver: collagen type IV, laminin, and fibronectin. Gut 1980;21:63-71. 10.1136/gut.21.1.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamkun JW, Hynes RO. Plasma fibronectin is synthesized and secreted by hepatocytes. J Biol Chem 1983;258:4641-7. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)32672-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu C, Chen T, Zeng W, et al. Reevaluating the prognostic significance of male gender for papillary thyroid carcinoma and microcarcinoma: a SEER database analysis. Sci Rep 2017;7:11412. 10.1038/s41598-017-11788-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdel-Rahman O. Clinical correlates and prognostic value of different metastatic sites in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Future Oncol 2017;13:1967-80. 10.2217/fon-2017-0175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayoub JP, Hess KR, Abbruzzese MC, et al. Unknown primary tumors metastatic to liver. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:2105-12. 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.6.2105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosch FX, Ribes J, Díaz M, et al. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology 2004;127: S5-16. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zibari GB, Riche A, Zizzi HC, et al. Surgical and nonsurgical management of primary and metastatic liver tumors. Am Surg 1998;64:211-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoe AL, Royle GT, Taylor I. Breast liver metastases--incidence, diagnosis and outcome. J R Soc Med 1991;84:714-6. 10.1177/014107689108401207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manfredi S, Lepage C, Hatem C, et al. Epidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 2006;244:254-9. 10.1097/01.sla.0000217629.94941.cf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kew MC. Hepatic tumors and cysts. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, Scharschmidt BF. editors. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology/Diagnosis/ Management. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002:1589-90. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clancy C, Burke JP, Barry M, et al. A Meta-Analysis to Determine the Effect of Primary Tumor Resection for Stage IV Colorectal Cancer with Unresectable Metastases on Patient Survival. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:3900-8. 10.1245/s10434-014-3805-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faron M, Pignon JP, Malka D, et al. Is primary tumour resection associated with survival improvement in patients with colorectal cancer and unresectable synchronous metastases? A pooled analysis of individual data from four randomised trials. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:166-76. 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tewes M, Peis MW, Bogner S, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for extensive liver metastases of breast cancer: efficacy, safety and prognostic parameters. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2017;143:2131-41. 10.1007/s00432-017-2462-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren Y, Dai C, Zheng H, et al. Prognostic effect of liver metastasis in lung cancer patients with distant metastasis. Oncotarget 2016;7:53245-53. 10.18632/oncotarget.10644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu F, Zhao J, Xie J, et al. Prognostic risk factors in patients with bone metastasis from colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol 2016;37:16127-34. 10.1007/s13277-016-5465-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baek SJ, Hur H, Min BS, et al. The Characteristics of Bone Metastasis in Patients with Colorectal Cancer: A Long-Term Report from a Single Institution. World J Surg 2016;40:982-6. 10.1007/s00268-015-3296-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khattak MA, Martin HL, Beeke C, et al. Survival differences in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer and with single site metastatic disease at initial presentation: results from South Australian clinical registry for advanced colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2012;11:247-54. 10.1016/j.clcc.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawamura H, Yamaguchi T, Yano Y, et al. Characteristics and Prognostic Factors of Bone Metastasis in Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61:673-8. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coleman RE. Skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer 1997;80:1588-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemke J, Scheele J, Kapapa T, et al. Brain Metastasis in Pancreatic Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:4163-73. 10.3390/ijms14024163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Go PH, Klaassen Z, Meadows MC, et al. Gastrointestinal cancer and brain metastasis: a rare and ominous sign. Cancer 2011;117:3630-40. 10.1002/cncr.25940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemke J, Barth TF, Juchems M, et al. Long-term survival following resection of brain metastases from pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res 2011;31:4599-603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumoto H, Yoshida Y. Brain metastasis from pancreatic cancer: A case report and literature review. Asian J Neurosurg 2015;10:35-9. 10.4103/1793-5482.151507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vanharanta S, Massagué J. Origins of Metastatic Traits. Cancer Cell 2013;24:410-21. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oda Y, Yamamoto H, Tamiya S, et al. CXCR4 and VEGF expression in the primary site and the metastatic site of human osteosarcoma: analysis within a group of patients, all of whom developed lung metastasis. Mod Pathol 2006;19:738-45. 10.1038/modpathol.3800587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L, Wang J. MicroRNA-mediated breast cancer metastasis: from primary site to distant organs. Oncogene 2012;31:2499-511. 10.1038/onc.2011.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato M, Kawana K, Adachi K, et al. Detachment from the primary site and suspension in ascites as the initial step in metabolic reprogramming and metastasis to the omentum in ovarian cancer. Oncol Lett 2018;15:1357-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]