Abstract

Including type strains, mitochondrial cytochrome b genes of 32 strains of Candida albicans and 6 strains of Candida stellatoidea, presently treated as a synonym for C. albicans, were partially sequenced. Analysis of 396-bp nucleotide sequences of the strains under investigation divided C. albicans isolates into three types: type I, type II, and type III; however, strains of C. stellatoidea represented distinct type IV isolates. Deduced amino acid sequences of type I, type II, and type III were identical and differed from that of type IV by one amino acid. Genotypes (rDNA type) of the test strains were also checked. Cytochrome b typing did not correlate with genotyping, and different genotypes occurred for one cytochrome b type. This study shows that cytochrome b gene sequences are useful for analyzing the genetic relatedness of C. albicans isolates and effective for differentiating C. stellatoidea from C. albicans.

Candida albicans continues to be the most frequently isolated causative agent of candidal infection in humans (more than 50%) and is generally accepted as the most pathogenic species of the genus Candida (4). The organism has been studied with numerous molecular biological techniques and characteristics to determine strain identity and strain variability: restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs), karyotypes, DNA probes, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analyses, nuclear DNA reassociations, mitochondrial DNA RFLPs, size and G + C content, protein electrophoretic profiles, as well as the phylogenetically determining criterion, rRNA gene sequences (19).

Usual morphological and physiological characterizations are not always sufficient for species designation. Meyer (17) established the conspecificity of Candida stellatoidea to C. albicans by DNA reassociation studies, supported by immunoelectrophoretic analysis (20) and confirmed by additional DNA reassociation studies (9). The opposite occurred when Sullivan et al. (23) described Candida dubliniensis, which resembles C. albicans in germ tubes and chlamydospores production, as a new species from the nucleotide differences of the V3 region of the large-subunit rRNA gene sequences of several atypical C. albicans strains. The proposal was supported by Gilfillan et al. (6) from the sequence studies of small rRNA genes and was confirmed by Donnelly et al. (5) based on the differences of the ACT1 intron and exon sequences of the two yeasts.

Strains of C. albicans are distributed into three genotypes—A, B, and C (15). C. dubliniensis had a distinct genotype, genotype D, and C. stellatoidea shared genotype with genotype B C. albicans. These genotypes are based on the PCR amplification product sizes (genotype A, a single band of ∼450 bp; genotype B, a single band of ∼840 bp; and genotype C, two bands of ∼450 and ∼840 bp) of the intron-containing region in the 25S rDNA (15).

C. stellatoidea was first isolated from the vaginal tracts of women by Jones and Martin (8) in 1937 and was described as a new species by Martin et al. (14). When the high DNA homology between C. stellatoidea and C. albicans was discovered, the phenotypic difference of sucrose assimilation was no longer considered to be sufficiently significant to warrant classifying these yeasts as separate species (17, 18, 19). The opinion over the taxonomic relationship between type I C. stellatoidea and C. albicans still differs. Kwon-Chung et al. (10) found two distinct genotypes among the isolates of C. stellatoidea, type I and type II. There is also evidence that C. stellatoidea type II does not express sucrose-inhibitable alpha-glucosidase and is a sucrose-negative mutant of C. albicans (12). However, type I C. stellatoidea cannot be treated as a simple mutant derived from C. albicans since it differs from C. albicans in several major genetic characteristics (11).

Our previous studies have shown that interspecies variations were more than 10 and 7%, respectively, for nucleotide and amino acid sequences for mitochondrial cytochrome b genes of the major pathogenic Candida species (25). Here we tested whether sequences of the cytochrome b gene could be used to discriminate intraspecific variants of the pathogenic yeast C. albicans or could be effective to differentiate C. albicans from C. stellatoidea. We also determined genotypes (rDNA types) of the tested C. albicans strains to determine the relationships of cytochrome b types and genotypes.

C. albicans strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. Total DNA extraction, PCR amplification of the cytochrome b gene, and direct DNA sequencing were carried out as described previously by Yokoyama et al. (25). The partial sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene determined in this study have been deposited in the DDBJ data library under the accession numbers shown in Table 1. DNA and deduced amino acid sequences were aligned using the program GENETYX-MAC Genetic Information Processing Software (Software Development Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and were analyzed by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA). Genotypes of the C. albicans strains in Table 1 were determined according to the method of McCullough et al. (15), amplifying the site of the transposable intron in the 25S rDNA.

TABLE 1.

C. albicans strains, strain origins, rDNA type (genotype), cytochrome b type, and accession numbers of cytochrome b genesa

| IFM strain no. | Source | rDNA type | Cytochrome b type | Cytochrome b accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4950 | Clinical isolate | A | I | AB051581 |

| 4953 | Clinical isolate | A | I | AB051582 |

| 5422a | Clinical isolate | A | IV | AB051583 |

| 5491a | Clinical isolate | B | IV | AB051584 |

| 5601 | Clinical isolate | A | II | AB051585 |

| 5602 | Clinical isolate | C | III | AB051586 |

| 5728 | IFO 0579 | A | I | AB044909b |

| 5745a | Clinical isolate | B | IV | AB051587 |

| 5772a | Clinical isolate | B | IV | AB051588 |

| 40009 | Clinical isolate | A | III | AB051589 |

| 40021a | Clinical isolate | B | IV | AB051590 |

| 40101 | Clinical isolate | B | II | AB051591 |

| 40102 | J. E. Cutler's lab, United States | A | I | AB051592 |

| 40213 | ATCC 90028 | A | I | AB051593 |

| 46462 | Clinical isolate | B | I | AB051594 |

| 46907 | TIMM 3163 | A | I | AB044910b |

| 46908 | TIMM 3164 | B | II | AB051595 |

| 46909 | TIMM 3165 | C | II | AB051596 |

| 46910 | TIMM 3166 | A | I | AB051597 |

| 47079 | Clinical isolate | A | I | AB051598 |

| 47259 | Clinical isolate | A | III | AB 51599 |

| 47596 | R. D. Cannon's lab, New Zealand | A | I | AB051600 |

| 47597 | R. D. Cannon's lab, New Zealand | C | I | AB051601 |

| 47601 | R. D. Cannon's lab, New Zealand | A | I | AB051602 |

| 48081 | Clinical isolate | A | II | AB051603 |

| 48107 | Clinical isolate | A | I | AB051604 |

| 48311 | CBS 562T | B | I | AB044911b |

| 48312a | CBS 1905T | B | IV | AB051605 |

| 48922 | Clinical isolate | A | I | AB044918b |

| 49685 | Clinical isolate | A | I | AB051606 |

| 49686 | Clinical isolate | C | I | AB044919b |

| 49689 | Clinical isolate | A | II | AB051607 |

| 49690 | Clinical isolate | C | I | AB051608 |

| 49691 | Clinical isolate | C | I | AB051609 |

| 49694 | Clinical isolate | C | I | AB051610 |

| 49700 | Clinical isolate | B | III | AB051611 |

| 49716 | Clinical isolate | B | I | AB051614 |

| 49768 | Clinical isolate | A | I | AB051615 |

Previous designation, C. stellatoidea.

Yokoyama et al. (25).

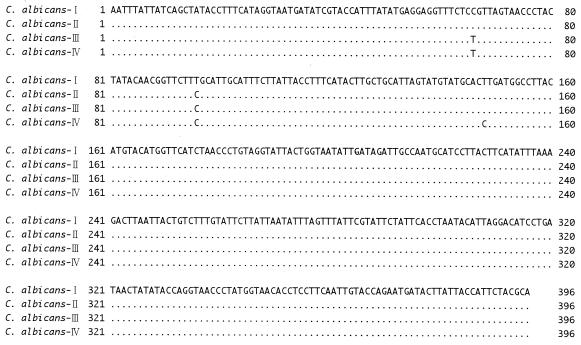

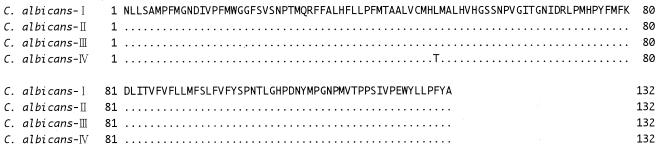

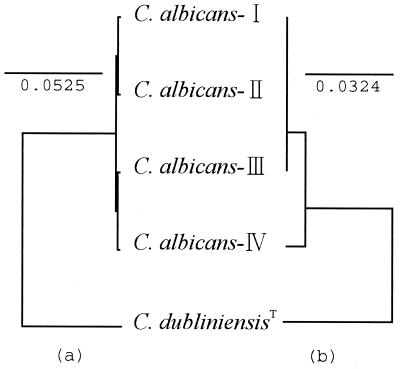

The cytochrome b gene type and genotype (rDNA type) of each C. albicans strain are shown in Table 1. Analysis of the 396-bp nucleotide sequence, corresponding to positions 445 to 840 in the Candida glabrata cytochrome b coding sequence (2, 25), indicated substitutions at only three positions (Fig. 1). Based on these differences, cytochrome b of C. albicans could be divided into four types: type I, type II, type III, and type IV (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Deduced amino acid sequence analysis indicated that only one of the three substitutions was nonsynonymous, and type I, type II, and type III strains represented identical amino acid sequences (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The type strain of C. albicans, IFM 48311 (CBS-562), had cytochrome b type I, and all strains of C. stellatoidea tested, including the type culture, IFM 48312 (CBS 1905), had cytochrome b type IV. (IFM is the Institute for Food Microbiology, presently at the Research Center for Pathogenic Fungi and Microbial Toxicoses, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan.) The type strain of C. albicans differed from the type strain of C. stellatoidea by three nucleotides and one amino acid in the cytochrome b gene sequences (Table 2). The UPGMA tree also represented the distinct position of C. stellatoidea (Fig. 3). The correlation of cytochrome b gene types and genotypes is shown in Table 3. For one cytochrome b type, different genotypes were found. However, the majority of strains of cytochrome b type I had genotype A, and the majority of strains of cytochrome b type IV had genotype B.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of cytochrome b genes of various types of C. albicans isolates. Dots indicate that the nucleotides are the same as those of C. albicans type I.

TABLE 2.

Numbers of nucleotide and amino acid differences between different cytochrome b gene types of C. albicans

| Cytochrome b gene type | No. of differences between typesa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | |

| I | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| II | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| III | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| IV | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

Data in the lower left portion of the table refer to nucleotide differences and data in the upper right portion refer to amino acid differences.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of deduced amino acid sequences of cytochrome b genes of various types of C. albicans isolates. Dots indicate that the amino acids are the same as those of C. albicans type I.

FIG. 3.

UPGMA-based trees representing the relationships of various types of C. albicans isolates, based on nucleotide (a) and deduced amino acid (b) sequences of the cytochrome b gene. The DDBJ accession no. of the C. dubliniensis type strain is AB044913 (26). Bars represent the numbers of nucleotide and amino acid substitutions per nucleotide and amino acid site.

TABLE 3.

Correlation of cytochrome b gene types and genotypes (rDNA) of C. albicans

| Cytochrome b

|

No. of strains of genotype:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | No. of strains | A | B | C |

| I | 22 | 14 | 3 | 5 |

| II | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| III | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| IV | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

Because of the relative ease and rapidity of performing the analyses, molecular biology-based methods, mainly restriction enzyme analysis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis karyotyping of chromosomal DNA, and RAPD analysis have become routinely used for DNA typing of C. albicans over the last decade. Each of the three methods has both benefits and drawbacks; however, restriction enzyme analysis and RAPD analysis methods of DNA typing of C. albicans isolates have greater discriminatory powers (>50 discrete subtypes by each method) than pulsed-field gel electrophoresis karyotyping (3). Molecular biology methods that have been used to differentiate type I C. stellatoidea from C. albicans are electrophoretic karyotyping (10, 11), mitochondrial DNA restriction fragment patterns (11), cellular DNA RFLPs (13), hybridization of cellular DNA with midrepeat probes (11), or electrophoretic pattern of total tRNA samples (22). The two yeasts can also be differentiated by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis analysis (21), by pyrolysis-mass spectrometry and Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy (24) or by fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis of oligosaccharides (7). Recent sequence-based studies have shown that C. stellatoidea differs from C. albicans by three bases in nucleotide sequences of group I self-splicing introns found in the large rRNA subunit (1), by four bases in the V2 region (1), and by only one or two bases in the V3 region (23).

This is the first step to use sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene for determination of the genetic relatedness of C. albicans isolates. Although C. stellatoidea is presently treated as a synonym for C. albicans (18), it is interesting that the type strain of C. albicans (cytochrome b type I) differs from the type strain of type I C. stellatoidea (cytochrome b type IV) by three bases, of which one is nonsynonymous, while the deduced amino acid sequences of type I, type II, and type III are identical. Five other C. stellatoidea strains examined in this study, IFM 5422, IFM 5491, IFM 5745, IFM 5772, and IFM 40021, represent identical sequences to the type strain of type I C. stellatoidea (IFM 48312). Except IFM 5422 (genotype A), all other C. stellatoidea strains represented genotype B. In another study, all isolates tested had genotype B (15). However, IFM 5422 is the only isolate that had an exception. Another interesting finding of this study is that the evolution of rDNA does not correlate with mitochondrial DNA such as the cytochrome b gene, at least for C. albicans strains, and as a result different rDNA types occurred for one cytochrome b type.

It has been postulated that there is a direct causal relationship between the presence of the group 1 intron in the 25S rDNA of C. albicans isolates (genotype B) and the level of resistance to flucytosine (16). This study did not include any strain resistant to flucytosine. However, four fluconazole-resistant strains (IFM 46907, IFM 46908, IFM 46909, and IFM 46910) included two that were genotype A, which does not contain the group 1 intron in the 25S rDNA, and the other two were genotype C, which contains two types of 25S rDNA showing both the presence and the absence of the group 1 intron.

In conclusion, this study has shown that cytochrome b gene sequences are useful for analyzing the genetic relatedness of C. albicans isolates. The study also reveals that cytochrome b sequences of type I C. stellatoidea differ from those of C. albicans at the nucleotide as well as amino acid levels.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Tokyo, Japan, for providing a scholarship to S. K. Biswas during the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boucher H, Mercure S, Montplaisir S, Lemay G. A novel group I intron in Candida dubliniensis is homologous to a Candida albicans intron. Gene. 1996;180:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark-Walker G D. Contrasting mutation rates in mitochondrial and nuclear genes of yeasts versus mammals. Curr Genet. 1991;20:195–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00326232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clemons K V, Feroze F, Holmberg K, Stevens D A. Comparative analysis of genetic variability among Candida albicans isolates from different geographic locales by three genotypic methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1332–1336. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1332-1336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman D C, Rinaldi M G, Haynes K A, Rex J H, Summerbell R C, Anaissie E J, Li A, Sullivan D J. Importance of Candida species other than Candida albicans as opportunistic pathogens. Med Mycol. 1998;36(Suppl. 1):156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donnelly S M, Sullivan D J, Shanley D B, Coleman D C. Phylogenetic analysis and rapid identification of Candida dubliniensis based on analysis of ACT1 intron and exon sequences. Microbiology. 1999;145:1871–1882. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-8-1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilfillan G D, Sullivan D J, Haynes K, Parkinson T, Coleman D C, Gow N A. Candida dubliniensis: phylogeny and putative virulence factors. Microbiology. 1998;144:829–838. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-4-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goins T L, Cutler J E. Relative abundance of oligosaccharides in Candida species as determined by fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2862–2869. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.8.2862-2869.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones C P, Martin D S. Identification of yeast like organisms isolated from the vaginal tracts of pregnant and non-pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1938;35:98–106. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamiyama A, Niimi M, Tokunaga M, Nakayama H. DNA homology between Candida albicans strains: evidence to justify the synonymous status of C. stellatoidea. Mycopathologia. 1989;107:3–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00437584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon-Chung K J, Wickes B L, Merz W G. Association of electrophoretic karyotype of Candida stellatoidea with virulence for mice. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1814–1819. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.7.1814-1819.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon-Chung K J, Riggsby W S, Uphoff R A, Hicks J B, Whelan W L, Reiss E, Magee B B, Wickes B L. Genetic differences between type I and type II Candida stellatoidea. Infect Immun. 1989;57:527–532. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.527-532.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon-Chung K J, Hicks J B, Lipke P N. Evidence that Candida stellatoidea type II is a mutant of Candida albicans that does not express sucrose-inhibitable α-glucosidase. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2804–2808. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.2804-2808.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magee B B, D'Souza T M, Magee P T. Strain and species identification by restriction fragment length polymorphisms in the ribosomal DNA repeat of Candida species. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1639–1643. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1639-1643.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin D S, Jones C P, Yao K F, Lee L E., Jr A practical classification of the Monilias. J Bacteriol. 1937;34:99–101. doi: 10.1128/jb.34.1.99-129.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCullough M J, Clemons K V, Stevens D A. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of genotypic Candida albicans subgroups and comparison with Candida dubliniensis and Candida stellatoidea. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:417–421. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.417-421.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mercure S, Montplaisir S, Lemay G. Correlation between the presence of a self-splicing intron in the 25S rDNA of C. albicans and strains susceptibility to 5-fluorocytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:6020–6027. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer S A. DNA relatedness between physiologically similar strains and species of yeasts of medical and industrial importance. In: Garratini S, Paglialunga S, Scrimshaw N S, editors. Investigation of single cell protein. New York, N.Y: Pergamon Press; 1979. pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer S A, Ahearn D G, Yarrow D. Genus 4. Candida Berkhout. In: Kreger-van Rij N J W, editor. The yeasts: a taxonomic study. 3rd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers B. V.; 1984. pp. 585–844. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer S A, Payne R W, Yarrow D. Candida Berkhout. In: Kurtzman C P, Fell J W, editors. The yeasts: a taxonomic study. 4th ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers B. V.; 1998. pp. 454–573. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montrocher R. Significance of immunoprecipitation in yeast taxonomy: antigenic analyses of some species within the genus Candida. Cell Mol Biol. 1980;26:293–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pujol C, Renaud F, Mallie M, de Meeus T, Bastide J M. Atypical strains of Candida albicans recovered from AIDS patients. J Med Vet Mycol. 1997;35:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos M A, el-Adlouni C, Cox A D, Luz J M, Keith G, Tuite M F. Transfer RNA profiling: a new method for the identification of pathogenic Candida species. Yeast. 1994;10:625–636. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan D J, Westerneng T J, Haynes K A, Bennet D E, Coleman D C. Candida dubliniensis sp. nov.: phenotypic and molecular characterization of a novel species associated with oral candidiasis in HIV-infected individuals. Microbiology. 1995;141:1507–1521. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timmins É, Howell S A, Alsberg B K, Noble W C, Goodacre R. Rapid differentiation of closely related Candida species and strains by pyrolysis-mass spectrometry and Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:367–374. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.367-374.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yokoyama K, Biswas S K, Miyaji M, Nishimura K. Identification and phylogenetic relationship of the most common pathogenic Candida species inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome b gene sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4503–4510. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.12.4503-4510.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]