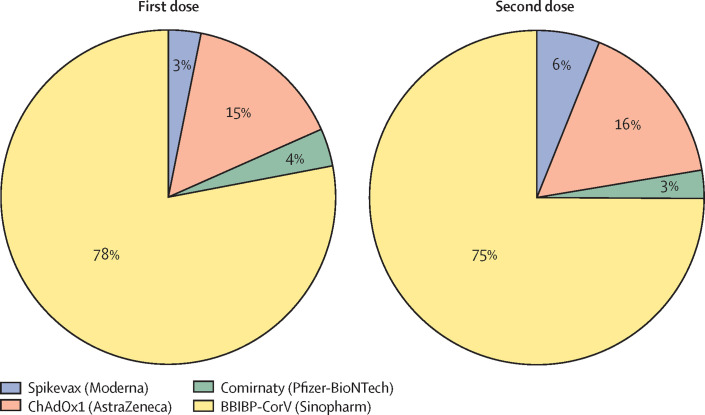

Bangladesh is listed among the 57 human resource for health (HRH) crisis countries as identified by the Global Health Workforce Alliance.1, 2 Despite shortages and maldistribution of health-care personnel, Bangladesh was known for successful immunisation campaigns even before the COVID-19 pandemic.3 The COVID-19 vaccination drive initially was not smooth for Bangladesh, but the country has, since July 2021, regained its reputation for strong vaccination efforts. COVID-19 vaccination started on Feb 7, 2021, with the ChAdOx1-nCoV-19 vaccine known as Covishield, (Serum Institute India [SII]). Vaccination was initially postponed while the SII suspended the export of vaccines as the number of COVID-19 infections in India increased. The Government of Bangladesh, however, managed to procure vaccines from alternative sources, which helped to alleviate its dependency on a single source. The Government intends to administer four different vaccines (Covishield, BBIBP-CorV [Sinopharm], Comirnaty [Pfizer-BioNTech], and Spikevax [Moderna]) to 170 million people in Bangladesh. As of December 13, 2021, Bangladesh has administered 86·5 million first doses and 43·3 million second doses (figure ),4 equating to roughly 50% of the total Bangladeshi population having received at least one dose and roughly 25% having been administered two doses of COVID-19 vaccines. Despite vaccine hesitancy and commonly held misconceptions about vaccines globally, vaccine acceptance among this population is encouraging. Like other low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC), Bangladesh has been supported by COVAX, which is co-led by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, WHO, and UNICEF to ensure equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines. After Indonesia, COVAX vaccine roll-out in Bangladesh ranks second highest among southeast Asian countries. This achievement is a monumental feat for Bangladesh given that high-income countries have already administered 69 times more doses than Bangladesh, showing a stratified and inequitable vaccine procurement and roll-out.5

Figure.

COVID-19 vaccination profile in Bangladesh as of December 13, 2021

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of WHO, notes that inequitable global distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine will burden LMICs most, resulting in a catastrophic moral failure.6 The possibility of this moral failure accentuates the importance of sharing technologies among manufacturers to enhance the capacity of vaccine manufacturing facilities in LMICs, which could then allow vaccines to be manufactured locally and complement global efforts to ensure equitable COVID-19 vaccine supply. Both Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and Muhammad Yunus, the only Nobel Laureate in Peace (2006) from Bangladesh, have been instrumental in a campaign to declare COVID-19 vaccines a global common good. This endeavour is a joint appeal from 3000 people including international personalities, Nobel Laureates, global leaders, international organisations, pharmaceutical companies, and governments.7 In addition to procuring vaccines from a diverse portfolio of manufacturers, Bangladesh has adopted a model to become self-reliant in vaccine manufacturing. A Bangladeshi biotech company, Globe Biotech, has completed non-human primate trials of its own mRNA-based vaccine and received approval for human trials.8 Additionally, other Bangladeshi vaccine manufacturing companies are capable of addressing the void in vaccine antigen production. Experts predict that the global COVID-19 vaccine supply could be substantially increased if vaccine manufacturers would share their efforts and technological knowledge with external manufacturers capable of vaccine production.5 For example, Incepta Vaccine Limited (IVL), the largest human vaccine manufacturing facility in Bangladesh, has signed a memorandum of understanding with Sinopharm, China, for production of the Sinopharm BBIBP-COVID-19 vaccine in Bangladesh. This collaboration will undoubtedly expedite the efforts of Bangladesh to produce viable COVID-19 vaccines in local settings. Along with contract manufacturing, IVL is also in the race to develop its own research and development based COVID-19 vaccine in collaboration with international institutes.9 Furthermore, Bangladesh has agreed to participate in a clinical trial for a novel nasal-route COVID-19 vaccine, developed by Karolinska Institute, Sweden.

With the increasing concern of waning vaccine immunity10 and effective results from heterologous vaccine priming and boosting,11, 12 Bangladesh should determine its policy and act quickly. Bangladesh has local vaccine research and production capacity at its disposal, along with four distinct COVID-19 vaccines. Looking forward, Bangladesh should focus on hosting clinical trials, including heterologous prime boost trials, to determine vaccine efficacy and long-term protection for its population. Although there is a debate on whether to administer a third vaccine dose as booster, evidence to support recommended schedules and target groups is scarce.13 A third dose for individuals who have already received two doses should be carefully considered only after two doses of the vaccine have been administered to the remaining unvaccinated people. To ensure maximum vaccine coverage, countries such as Bangladesh should allocate resources to local manufacturers and support large-scale research efforts, clinical trials, cold-chain technology, and international collaboration. Support could be in the form of subsidies, duty-free import of research items, or tax incentives for vaccine manufacturers and research organisations.

To bring this pandemic under control, more than 75% of the global population must be vaccinated.14 This goal becomes increasingly challenging given the unequal distribution and hoarding of vaccines by high-income countries. This inequality could be obviated, however, by strict adherence to the procurement and supply operation under the COVAX initiative. This mandate should serve as a reference for ensuring equitable global access to the COVID-19 vaccine. Discrete high vaccination performance and travel bans from high-income countries will not only be futile in bringing the pandemic under control but will also put all nations at risk unless the global population is universally vaccinated.15 Initiatives should be undertaken to acquire and distribute vaccines among LMICs. Without such initiatives there remains a growing concern for the persistent presence of COVID-19 hot spots in low-income countries, which increases the risk of escape variants of SARS-COV-2.

We declare no competing interests. We would like to acknowledge Nikki Kelvin for editing this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Genome Canada/Atlantic Genome, Research Nova Scotia, Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation, and the Li-Ka Shing Foundation.

References

- 1.WHO The human resources for health crisis. 2011. https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/countries/bgd/en/

- 2.WHO Bangladesh. https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/countries/bgd/en/

- 3.Sarma H, Budden A, Luies SK, et al. Implementation of the world's largest measles-rubella mass vaccination campaign in Bangladesh: a process evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:925. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7176-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DGHS COVID-19 dashboard for Bangladesh. http://103.247.238.92/webportal/pages/covid19-vaccination-update.php

- 5.Burki T. Global COVID-19 vaccine inequity. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:922–923. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00344-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO WHO Director-Generals opening remarks at 148th session of the Executive Board. Jan 18, 2021. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-148th-session-of-the-executive-board

- 7.Yunus M, Donaldson C, Perron J-L. COVID-19 vaccines a global common good. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2020;1:e6–e8. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(20)30003-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Business Standard Globe biotech gets BMRC nod for human trials. https://www.tbsnews.net/coronavirus-chronicle/covid-19-bangladesh/globe-biotech-gets-bmrc-nod-human-trials-333622

- 9.Baylor College of Medicine Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital collaborate with Incepta Vaccine Ltd. to develop a COVID-19 vaccine for Bangladesh. https://www.bcm.edu/news/baylor-college-of-medicine-and-texas-childrens-hospital-collaborate-with-incepta-vaccine-ltd-to-develop-a-covid-19-vaccine-for-bangladesh

- 10.Pegu A, O'Connell S, Schmidt SD, et al. Durability of mRNA-1273 vaccine-induced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science. 2021;373:1372–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.abj4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barros-Martins J, Hammerschmidt SI, Cossmann A, et al. Immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 variants after heterologous and homologous ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/BNT162b2 vaccination. Nat Med. 2021;27:1525–1529. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01449-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw RH, Stuart A, Greenland M, Liu X, Nguyen Van-Tam JS, Snape MD. Heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccination: initial reactogenicity data. Lancet. 2021;397:2043–2046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01115-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Lancet Infectious Diseases COVID-19 vaccine equity and booster doses. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00486-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreier F. Unprecedented achievement: who received the first billion COVID vaccinations? https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01136-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Mendelson M, Venter F, Moshabela M, et al. The political theatre of the UK's travel ban on South Africa. Lancet. 2021;398:2211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02752-5. 13.v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]