Keywords: climate change, environmental extremes, heat balance, heat stress, thermoregulation

Abstract

Critical environmental limits are those combinations of ambient temperature and humidity above which heat balance cannot be maintained for a given metabolic heat production, limiting exposure time, and placing individuals at increased risk of heat-related illness. The aim of this study was to establish those limits in young (18–34 yr) healthy adults during low-intensity activity approximating the metabolic demand of activities of daily living. Twenty-five (12 men/13 women) subjects were exposed to progressive heat stress in an environmental chamber at two rates of metabolic heat production chosen to represent minimal activity (MinAct) or light ambulation (LightAmb). Progressive heat stress was performed with either 1) constant dry-bulb temperature (Tdb) and increasing ambient water vapor pressure (Pa) (Pcrit trials; 36°C, 38°C, or 40°C) or 2) constant Pa and increasing Tdb (Tcrit trials; 12, 16, or 20 mmHg). Each subject was tested during MinAct and LightAmb in two to three experimental conditions in random order, for a total of four to six trials per participant. Higher metabolic heat production (P < 0.001) during LightAmb compared with MinAct trials resulted in significantly lower critical environmental limits across all Pcrit and Tcrit conditions (all P < 0.001). These data, presented graphically herein on a psychrometric chart, are the first to define critical environmental limits for young adults during activity resembling those of light household tasks or other activities of daily living and can be used to develop guidelines, policy decisions, and evidence-based alert communications to minimize the deleterious impacts of extreme heat events.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Critical environmental limits are those combinations of temperature and humidity above which heat balance cannot be maintained, placing individuals at increased risk of heat-related illness. Those limits have been investigated in young adults during exercise at 30% V̇o2max, but not during metabolic rates that approximate those of light activities of daily living. Herein, we establish critical environmental limits for young adults at two metabolic rates that reflect activities of daily living and leisurely walking.

INTRODUCTION

The average temperature of the Earth has been steadily increasing for several decades and is expected to continue increasing throughout the 21st century (1). Along with the increase in average global temperatures, the frequency, duration, and severity of heat waves have increased (2). Epidemiological data support a strong association between heat waves and excess mortality. During the Chicago heat wave in 1995, there were ∼700 excess deaths compared with the same days in the previous year (3). In 2003, a heat wave of nine consecutive days in France was estimated to have caused nearly 15,000 excess deaths (4). Excess mortality was increased in California by 4.3% for every 5.6°C increase in apparent temperature when temperatures were above the 90th percentile (5). In 15 cities across Europe, an increase in apparent temperature of 1°C above a threshold temperature unique to each city was associated with a ≥2% increase in mortality (6). Together, these data illustrate the critical need for research targeted toward understanding the environmental conditions associated with heat- and humidity-related morbidity and mortality.

Critical environmental limits are defined as those combinations of environmental conditions (temperature and humidity) above which heat balance cannot be maintained for a given metabolic heat production (7–11). A time-intensive, progressive heat stress protocol was developed by Belding and Kamon (12) to determine critical ambient water vapor pressures (Pcrit) at 36°C during exercise at various intensities and air movement velocities. That protocol was refined by our laboratory and used to identify critical environmental limits for prolonged heat exposure in various populations or clothing ensembles across a range of ambient dry-bulb temperatures (Tdb) and water vapor pressures (Pa) (7–10, 13, 14), primarily at moderate work intensities within the context of industrial settings.

Empirically derived critical environmental limits can be plotted on a psychrometric chart and used to develop evidence-based alert communication, policy decisions, triage for impending heat events, and implementation of other safety interventions during extreme heat events. Previous data from our laboratory have established critical environmental limits for young men and women (10) and older unacclimated women (14) during exercise at 30% V̇o2max — a work rate that reflects the intensity associated with an 8-h work day in many industrial settings (15). However, critical environmental limits during very light physical activity, approximating the intensity of daily activities such as household tasks or leisurely walking, have yet to be established. To develop targeted policy and safety interventions to mitigate the impact of future heat events, it is important to establish critical environmental limits for various subpopulations during physical activity at metabolic work rates that are relevant among free-living adults. That is the overarching goal of the PSU HEAT (Human Environmental Age Thresholds) project. Although aged populations are most at risk in extreme environments, it is important to first establish these limits for young healthy adults to establish a baseline for comparative purposes.

Therefore, the purpose of this investigation was to establish critical environmental limits for healthy young adults at two low metabolic intensities that reflect activities of daily living and slow walking. We hypothesized that critical environments would be shifted downward and leftward on a psychrometric chart at higher compared with lower rates of metabolic heat production. By establishing psychrometric limits in a young, healthy population, the findings of this study will be used against which to compare future studies in vulnerable populations.

METHODS

Subjects

All experimental procedures received ethics approval from the Institutional Review Board at The Pennsylvania State University and conformed to the guidelines set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. After all aspects of the experiment were explained, oral and written informed consent was obtained. Twenty-five healthy men (n = 12) and women (n = 13) aged 18– 34 yr were tested at two light levels of activity in two to three environmental conditions, in random order, for a total of four to six trials per participant.

All subjects were healthy, normotensive (blood pressure was measured using brachial auscultation after 10 min quiet rest), nonsmokers, and not taking any medications that might affect the physiological variables of interest in this study. No attempt was made to control for menstrual status or contraceptive use. Acclimatization status was not accounted for (“see LIMITATIONS”). Maximal aerobic capacity (V̇o2max) was determined with the use of open-circuit spirometry (Parvo Medics TrueOne 2400, Parvo, UT) during a maximal graded exercise test performed on a motor-driven treadmill. During the experiments, clothing was standardized with subjects wearing thin, short-sleeved cotton tee-shirts, a sports bra for women, shorts, socks, and walking/running shoes.

Testing Procedures

Experimental trials were conducted on separate days with at least 72 h between visits. Participants were asked to abstain from caffeine consumption for at least 12 h, and alcohol consumption or vigorous exercise for 24 h, before arrival for experimental trials. Upon arrival at the laboratory, participants provided a urine sample to ensure euhydration, defined as urine specific gravity ≤ 1.020 (USG; PAL-S, Atago, Bellevue, WA) (16). Subjects performed light activity in an environmental chamber at two intensities reflecting the metabolic demand of minimal physical activity (MinAct) or light ambulatory activity (LightAmb) (17, 18). Subjects cycled on a cycle ergometer (Lode Excalibur, Groningen, The Netherlands) against zero resistance at a cadence of 40–50 rpm for MinAct trials and walked on a motor-driven treadmill at a speed of 2.2 mi/h and grade of 3% for LightAmb trials. All experiments began between the hours of 0800 h and 1500 h; thus, although minor differences in absolute core temperature may have existed due to time of testing (19), the biophysics of heat exchange, and therefore the critical environmental conditions, was unlikely to have been affected by circadian rhythm.

During Pcrit trials, Tdb was held constant at either 36°C, 38°C, or 40°C. During Tcrit trials, Pa was held constant at either 12, 16, or 20 mmHg. After a 30-min equilibration period, either the Tdb (Tcrit tests) or the Pa (Pcrit tests) in the environmental chamber was increased in a stepwise fashion (1°C or 1 mmHg every 5 min), whereas chamber Tdb and subject gastrointestinal temperature (Tgi) and HR were monitored. During each experiment, subjects pedaled or walked continuously until a clear rise in Tc was observed. With no forced air movement in the environmental chambers, air movement velocity has been measured at 0.45 m/s (10).

Measurements

Gastrointestinal temperature telemetry capsules (VitalSense, Philips Respironics, Bend, OR) were provided for subjects to ingest 1–2 h before reporting to the laboratory in accordance with previously published data indicating that ingestion times ranging from 1 to 12 h before use do not influence the precision of Tgi data (20). Tgi data were continuously measured and transmitted to a PowerLab data acquisition system and LabChart signal processing software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO) using an Equivital wireless physiological monitoring system (Equivital Inc., New York, NY). We have previously demonstrated excellent concurrence between rectal and gastrointestinal temperatures for the determination of the Tc inflection point (ICC = 0.93) (11).

Skin temperature was measured continuously (iButton, Whitewater, WI) at four sites: chest (Tch), arm (Tarm), thigh (Tth), and lower leg (Tleg). A weighted mean skin temperature () was calculated (21) as

| (1) |

Oxygen consumption (V̇o2; L/min) and respiratory exchange ratio (RER; unitless) were determined at two time points (5 and 60 min after the onset of exercise) using indirect calorimetry (Parvo Medics TrueOne 2400, Parvo, UT). Metabolic rate [M; Watts (W)], normalized to body surface area, was calculated from V̇o2 and RER (22) as

| (2) |

where AD is the Dubois surface area (m2). For treadmill walking trials, external work (W; W/m2) was calculated as

| (3) |

where mb is the body mass (kg), Vw is the walking velocity (m/min), and fg is the fractional grade of the treadmill (22). For cycling trials, W was assumed to be zero. Net metabolic heat production (Mnet) was calculated as M − W.

To compare work rates in terms of metabolic equivalents (METs) to previous data (17) detailing the metabolic costs of various household tasks, METs were calculated using V̇o2 in mL·kg−1·min−1, assuming a resting V̇o2 of 3.5 mL·kg−1·min−1 (23), as

| (4) |

Dry heat exchange via radiation and convection (W·m−2) was determined as

| (5) |

where hr+c (in W·m−2·°C−1) is the combined radiative and convective heat transfer coefficient and Tdb– represents the temperature gradient between the ambient air and the skin. In this study, hr+c was determined for each subject by using the formula

| (6) |

where 6.5·(treadmill speed in m·s−1)0.39 is the convective coefficient for treadmill walking and 4.7 is the radiative coefficient for indoor environments.

Heat storage (S; W·m−2) was calculated as

| (7) |

where 0.97 W·h·kg−1·°C−1 is the specific heat of the body and Δ represents the change in mean body temperature measured over the time period (Δt in h) between 30 min and the time at which the critical Tes inflection point was observed. The equation for Δ (°C), which is a function of the change in Tes and , was

| (8) |

Maximal evaporative capacity of the environment (Emax in W·m−2) was calculated as

| (9) |

where v was assumed to be 0.45 m/s based on past studies that used the same environmental chambers (10, 14). At each critical environmental condition, the evaporative cooling required to maintain thermal balance (Ereq) equals Emax, i.e.,

| (10) |

And the heat balance equation can be solved for Ke′. This solution assumes a fully wetted skin surface, a requirement that, as expected, was met only in the Pcrit tests.

Sweat rate was determined from the loss of nude body mass on a scale accurate to ±10 g. Fluid intake was prohibited between the initial and final measurements of nude body mass.

Determination of Tcrit and Pcrit

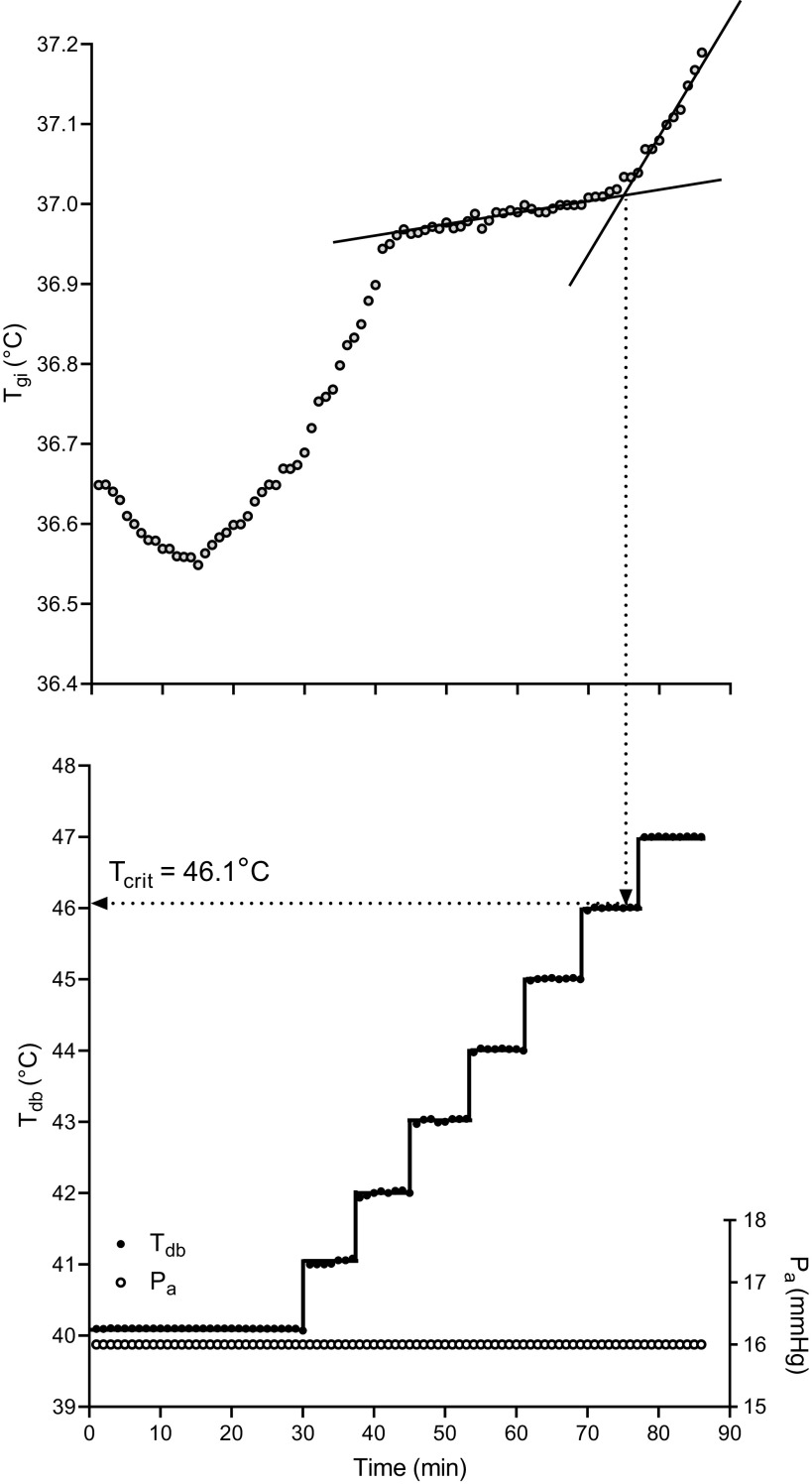

Figure 1 provides a representative tracing of the time course of gastrointestinal temperature (Tgi), dry-bulb temperature (Tdb), and ambient water vapor pressure (Pa) for a MinAct trial with increasing Tdb. After an initial rise, Tgi typically began to plateau after 30–40 min and remained at an elevated, relative steady state [a slow rise in Tgi is observed in some unacclimated subjects, constituting positive heat storage (10)] proportional to metabolic heat production, as Tdb or Pa was systematically increased in a stepwise fashion as described previously. A clear Tgi inflection was observed in all cases except in one subject during a 38°C Pcrit MinAct trial, for which data were excluded. The critical Tdb or Pa was characterized by a subsequent upward inflection of Tgi from steady state, which was selected graphically from the raw data. A line was drawn between the data points, starting at the 30th min. A second line was drawn from the point of departure from the Tgi equilibrium phase slope. The average Tdb or Pa for the 2 min immediately preceding the inflection point was defined as the critical Tdb or Pa, respectively. Inflection points were determined by visual inspection, as previously reported (10, 11, 14). We have previously demonstrated excellent intrarater reliability for the determination of the Tc inflection point (ICC = 0.93) (11).

Figure 1.

Representative tracing of the time course of core temperature (gastrointestinal temperature, Tgi), dry-bulb temperature (Tdb), and ambient water vapor pressure (Pa) for a MinAct trial with increasing Tdb. Lines are drawn through data points in the bottom panel to demonstrate the stepwise progression of Tdb. The Tgi inflection point represents the combination of environmental conditions above which heat stress becomes uncompensable and a stable core temperature can no longer be maintained. In this case, the Tgi inflection point (i.e., critical dry bulb temperature, Tcrit) occurs at Tdb = 46.1°C.

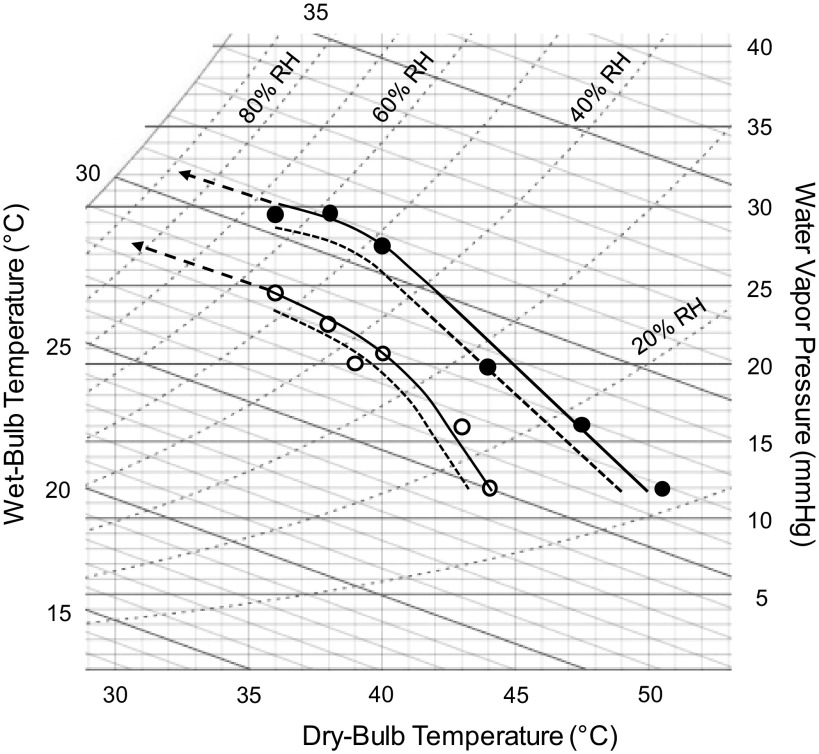

Psychrometric loci were plotted on a standardized psychrometric chart from the mean data for combinations of Tdb and Pa (“see Fig. 2 in RESULTS”). To construct isothermal lines as a continuation of the curves plotted on a psychrometric chart from empirically derived data (“see Fig. 2 in RESULTS”), we calculated the slope of the line using and mean Ke′·v0.6 values determined in this study (10, 14) as

| (11) |

Figure 2.

A standard psychrometric chart showing empirically derived mean critical environmental limits (symbols and solid lines) for light ambulatory activity (LightAmb; open circles) and minimal activity (MinAct; filled circles) trials. The larger dashed lines with arrows at the top left portion of the curves are isothermal lines from biophysical modeling of heat exchange, as described in methods. Smaller dashed lines denote the lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval for each condition. Critical environmental limits were significantly lower (i.e., shifted downward and to the left; P < 0.001) in LightAmb compared with MinAct across all environmental conditions tested.

Because the calculation of Ke′ is dependent upon fully wetted skin, slopes were calculated for 36°C and 38°C Pcrit trials only. Isothermal lines were constructed using the average of the two slopes for each exercise intensity.

Statistical Analysis

An a priori power analysis using an effect size of 1.2, based on previously published Pcrit data (13, 14), suggested that seven subjects would yield sufficient statistical power (power ≥ 0.8, α = 0.005) to detect significant differences in Tcrit and Pcrit between exercise intensities. Because each subject completed trials in multiple conditions, but not every condition, we opted to perform separate paired-samples t tests (SPSS, v. 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) to compare Mnet, sweat rate, and V̇o2 data between environmental conditions and exercise intensities. Similarly, differences in Tcrit and Pcrit due to exercise intensity were analyzed using paired-samples t tests. For metabolic heat production, sweat rates, and V̇o2, to account for multiple comparisons within and between physical activity intensities among environmental conditions (30 comparisons), significance was accepted at α = 0.002. For critical environmental limits, to account for multiple comparisons between physical activity intensities (6 comparisons), significance was accepted at α = 0.008. Data are reported as means ± SD except in Fig. 2 which is presented with mean data and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

Subject characteristics are presented in Table 1. Subjects were recruited to be representative of the population in this age group with respect to body size, adiposity, and aerobic fitness. There were no subject sample differences in age, height, weight, AD, AD·kg−1, or V̇o2max among trial conditions (all P ≥ 0.05).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Characteristic | Means ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 24 ± 4 | 18–34 |

| Height, m | 1.72 ± 0.1 | 1.57–1.98 |

| Weight, kg·m−2 | 71 ± 12 | 52–98 |

| AD, m2 | 1.84 ± 0.20 | 1.50–2.31 |

| AD·kg−1, m2·kg−1 | 0.026 ± 0.002 | 0.022–0.029 |

| V̇o2max, mL·kg−1·min−1 | 49 ± 12 | 30–79 |

n = 25; 12 M/13 W. AD, DuBois body surface area; AD·kg−1, body surface area-to-mass ratio; V̇o2max, maximal oxygen consumption.

Metabolic Heat Production, Sweat Rate, and V̇o2

The grand means (i.e., mean for all trials across environmental conditions) for Mnet (82.9 ± 12.5 W·m−2 vs. 133.3 ± 14.8 W·m−2), sweat rate (142.8 ± 80.2 g·m−2·h−1 vs. 230.8 ± 84.9 g·m−2·h−1), percent body mass loss (0.70 ± 0.42% vs. 1.04 ± 0.44%), and V̇o2 (0.46 ± 0.10 L·min−1 vs. 0.80 ± 0.16 L·min−1) were lower for MinAct compared with LightAmb (all P < 0.0001). Likewise, METs (unitless) were lower in MinAct compared with LightAmb (1.81 ± 0.26 vs. 3.19 ± 0.30; P < 0.0001). Summary data for metabolic heat production, sweat rate, and V̇o2 within each trial are presented in Table 2. There were no differences in Mnet (P ≥ 0.16), sweat rate (P ≥ 0.05), percent body mass loss (P > 0.002), or V̇o2 (P > 0.12) among environmental conditions for either MinAct or LightAmb intensities. Mnet (all P < 0.0001) and V̇o2 (P ≤ 0.002) were lower during MinAct trials compared with LightAmb trials. Sweat rate was significantly lower in MinAct compared with LightAmb trials in 36°C and 20 mmHg conditions (P ≤ 0.001). However, sweat rates were marginally, but not significantly, different between MinAct and LightAmb within all other environmental conditions (P ≥ 0.02). Percent body mass loss was different between MinAct and LightAmb only in 36°C and 12 mmHg conditions (P ≤ 0.006).

Table 2.

Sex distribution, metabolic heat production, sweat rates, and V̇o2 for each experimental condition (means ± SD)

| 36°C | 38°C | 40°C | 20 mmHg | 16 mmHg | 12 mmHg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| MinAct | 4 M / 5 W | 5 M / 3 W | 4 M / 5 W | 6 M / 3 W | 4 M / 5 W | 4 M / 5 W |

| LightAmb | 4 M / 5 W | 5 M / 4 W | 4 M / 5 W | 6 M / 3 W | 4 M / 5 W | 4 M / 5 W |

| Mnet, W·m−2 | ||||||

| MinAct | 77.9 ± 15.7 | 82.6 ± 17.1 | 80.4 ± 8.5 | 81.5 ± 11.4 | 87.7 ± 10.7 | 87.4 ± 12.3 |

| LightAmb | 128.5 ± 17.5* | 136.0 ± 15.8* | 133.5 ± 13.2* | 130.3 ± 10.3* | 134.4 ± 14.5* | 137.3 ± 18.7* |

| SR, g·m−2·h−1 | ||||||

| MinAct | 117.1 ± 84.5 | 179.7 ± 105.4 | 147.5 ± 70.4 | 103.9 ± 41.2 | 140.9 ± 62.2 | 171.8 ± 98.2 |

| LightAmb | 211.9 ± 68.6* | 273.6 ± 107.3 | 262.6 ± 87.4 | 187.4 ± 37.9* | 205.7 ± 74.3 | 243.3 ± 101.7 |

| V̇o2, L·min−1 | ||||||

| MinAct | 0.41 ± 0.11 | 0.47 ± 0.11 | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.10 | 0.49 ± 0.09 | 0.47 ± 0.11 |

| LightAmb | 0.73 ± 0.15* | 0.80 ± 0.17* | 0.80 ± 0.16* | 0.82 ± 0.15* | 0.80 ± 0.14* | 0.79 ± 0.18* |

| BML, % | ||||||

| MinAct | 0.55 ± 0.44 | 0.81 ± 0.52 | 0.80 ± 0.42 | 0.50 ± 0.19 | 0.66 ± 0.30 | 0.86 ± 0.53 |

| LightAmb | 0.98 ± 0.45* | 1.33 ± 0.48 | 1.22 ± 0.40 | 0.71 ± 0.15 | 0.93 ± 0.41 | 1.09 ± 0.45* |

BML, body mass loss; LightAmb, light ambulatory activity; M, men; mnet, metabolic heat production; MinAct, minimal activity; SR, sweat rate; W, women. * P < 0.002 compared with MinAct.

Critical Environmental Limits

Figure 2 depicts critical environmental loci plotted on a standard psychrometric chart with lower bounds of the 95% CI. Heat stress is compensable in environmental conditions that are below and to the left of each line. In every environmental condition, psychrometric limits were shifted downward and leftward for LightAmb compared with MinAct trials (all P < 0.001). Summary data for Tdb, Pa, and relative humidity (RH) are presented in Table 3. During Pcrit trials, RH at the Tc inflection point was higher during MinAct compared with LightAmb (P ≤ 0.002). Conversely, during Tcrit trials, RH at the inflection point was lower during MinAct compared with LightAmb (P ≤ 0.005). Lower RH in MinAct compared with LightAmb during Tcrit trials was a function of higher Tdb at a given Pa.

Table 3.

Environmental conditions at the core temperature inflection point for each experimental condition (means ± SD)

| 36°C | 38°C | 40°C | 20 mmHg | 16 mmHg | 12 mmHg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tdb, °C | ||||||

| MinAct | 36.0 ± 0.2 | 37.9 ± 0.3 | 40.0 ± 0.2 | 43.8 ± 2.0 | 47.3 ± 1.6 | 50.6 ± 2.0 |

| LightAmb | 35.9 ± 0.1 | 38.0 ± 0.3 | 40.1 ± 0.4 | 38.9 ± 1.0* | 43.0 ± 1.5* | 44.5 ± 2.4* |

| Pa, mmHg | ||||||

| MinAct | 29.6 ± 2.2 | 29.8 ± 2.3 | 27.7 ± 2.4 | 19.7 ± 0.7 | 16.3 ± 0.4 | 12.0 ± 0.4 |

| LightAmb | 24.6 ± 1.7* | 22.6 ± 1.0* | 20.7 ± 1.8* | 20.0 ± 0.4 | 16.1 ± 0.2 | 12.1 ± 0.5 |

| RH, % | ||||||

| MinAct | 66.4 ± 5.4 | 60.5 ± 5.1 | 50.2 ± 4.3 | 29.2 ± 2.8 | 20.3 ± 1.5 | 12.7 ± 1.5 |

| LightAmb | 55.5 ± 3.9* | 45.5 ± 2.7* | 37.3 ± 3.3* | 38.4 ± 1.8* | 24.9 ± 2.0* | 18.6 ± 3.3* |

LightAmb, light ambulatory activity; MinAct, minimal activity; pa, water vapor pressure; RH, relative humidity; Tdb, dry-bulb temperature. *P < 0.005 compared with MinAct.

DISCUSSION

The PSU HEAT Study is an ongoing project designed to determine critical environmental limits beyond which thermal balance with the environment is not possible. Although the overarching goal of PSU HEAT is to determine such untenable environments for aged and other vulnerable populations, the purpose of this study was to establish critical environmental limits for the maintenance of heat balance in young, healthy adults during very low-intensity physical activity that approximates the metabolic demand of activities of daily living or leisurely walking. As expected, our findings demonstrated that critical environmental limits are shifted toward lower combinations of temperature and humidity as Mnet is increased. The lower bounds of the 95% confidence intervals theoretically provide upper limits below which most young, healthy adults can maintain a steady state, albeit elevated, core temperature at these low metabolic rates. The data from this study may be used to develop evidence-based alert communications, policy decisions, triage for impending heat events, and implementation of other safety interventions during extreme heat events for healthy, young adults.

Progressive heat stress protocols have been used extensively to determine safe upper limits of heat and humidity for industry work in various clothing ensembles (9, 24–27). Only one study has established psychrometric limits for young, healthy adults wearing clothing similar to that of the present study (10), which was meant to more closely simulate the clothing that would likely be worn in the heat during activities of daily living. In that study, however, subjects walked at an intensity equal to 30% of V̇o2max because that intensity reflects the intensity associated with an 8-h work day in industry settings, as well as many self-paced activities in young, healthy adults. For the current study, we included mild physical activity at metabolic rates that approximate those of light activities of daily living such as gardening or leisurely walking. Indeed, the metabolic cost of the LightAmb (∼0.8 L/min; ∼3.2 METs) and MinAct (∼0.45 L/min; ∼1.8 METs) trials in this study closely resembled the metabolic costs of self-selected walking speed and various household tasks (e.g., watering or fertilizing the lawn), respectively, in young and older adults (17, 18). As such, these findings provide the most relevant data to date regarding safe upper limits for heat stress exposure in free-living healthy, young adults.

When the critical limits for heat balance are plotted on a psychrometric chart, the curvilinear relation between water vapor pressure and dry-bulb temperature is explained by the transition from fully wetted skin at the upper left portion of the curve to free evaporation at the lower right portion of the curve. The slope is constrained in the upper left portion of the curve because a relatively small water vapor pressure gradient between the skin and the environment limits the maximal capacity for evaporative cooling. In hotter, drier ambient environments (i.e., the lower right aspect of the curve), the limit to heat balance is defined by maximal sweating capacity, resulting in a more vertical slope, particularly at higher metabolic rates. As demonstrated by Fig. 2, the slope of the line in hot, dry ambient conditions becomes steeper during LightAmb compared with MinAct trials. The wider and more linear nature of that portion of the curve in MinAct trials can be explained by significantly lower metabolic heat production, and therefore a lower requirement for evaporative heat loss, but only marginally different sweating rates with free evaporation. A similar widening of the curve at lower ambient water vapor pressures has been demonstrated in heat acclimated compared with unacclimated young women working at similar metabolic rates (14), explained by increased sweating rates in the acclimated women.

Potential Limitations

No attempt was made in this study to account for heat acclimatization. However, subjects were tested throughout the year, with enough participants being tested during each season to eliminate the potential for acclimatization status to influence differences between experimental conditions. Future research will examine the impact of seasonality/heat acclimatization on critical environmental limits in a larger cohort of young men and women.

We likewise did not attempt to control for menstrual cycle or contraceptive use in female participants. Although absolute Tc varies across the menstrual cycle, the change in Tc during exercise in the heat is unaffected (28). Similarly, Tc profiles during exercise in the heat are similar across menstrual phases (11). Thus, it is unlikely that the observed critical environmental limits were influenced by not controlling for menstrual cycle or contraceptive use.

Finally, this study was not powered to assess potential sex differences in critical environmental limits. However, a long-term goal of the PSU HEAT project is to test enough participants to determine whether sex differences exist.

Perspectives and Significance

The present investigation was focused solely on establishing critical environmental limits in young, healthy adults during physical activity at two low metabolic rates. Age-related impairments in thermoregulatory function (29, 30), as well as increased morbidity and mortality in older adults during extreme heat events (29, 31, 32), are well-established. However, there has been minimal investigation into the specific environmental conditions above which older adults are at increased risk heat-related illness. Only one study has demonstrated critical environmental limits in older (62–80 yr) unacclimated women during 30% V̇o2max exercise (14). There has yet to be investigation of those psychrometric limits in older men and women during physical activity that approximates the metabolic demand of light activities of daily living. The data presented herein provide a point of comparison against which future research will answer the question: in what combinations of environmental conditions do age differences in thermoregulatory function result in greater heat loads in older adults, thus placing them at increased risk of heat-related morbidity and mortality?

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01 AG067471 (to W.L.K.) and NIA Grant T32 AG049676 (to D.J.V.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.T.W. and W.L.K. conceived and designed research; S.T.W., R.M.C., and D.J.V. performed experiments; S.T.W. and R.M.C. analyzed data; S.T.W., R.M.C., and W.L.K. interpreted results of experiments; S.T.W. prepared figures; S.T.W. drafted manuscript; S.T.W., R.M.C., D.J.V., and W.L.K. edited and revised manuscript; S.T.W., R.M.C., D.J.V., and W.L.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful for the subject’s participation and for the assistance of Susan Slimak, RN.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee H. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perkins S, Alexander L, Nairn J. Increasing frequency, intensity and duration of observed global heatwaves and warm spells. Geophys Res Lett 39: 20714, 2012. doi: 10.1029/2012GL053361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitman S, Good G, Donoghue ER, Benbow N, Shou W, Mou S. Mortality in Chicago attributed to the July 1995 heat wave. Am J Public Health 87: 1515–1518, 1997. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.9.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouillet A, Rey G, Laurent F, Pavillon G, Bellec S, Guihenneuc-Jouyaux C, Clavel J, Jougla E, Hémon D. Excess mortality related to the August 2003 heat wave in France. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 80: 16–24, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00420-006-0089-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basu R, Malig B. High ambient temperature and mortality in California: exploring the roles of age, disease, and mortality displacement. Environ Res 111: 1286–1292, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baccini M, Biggeri A, Accetta G, Kosatsky T, Katsouyanni K, Analitis A, Anderson HR, Bisanti L, D’Ippoliti D, Danova J, Forsberg B, Medina S, Paldy A, Rabczenko D, Schindler C, Michelozzi P. Heat effects on mortality in 15 European cities. Epidemiology 19: 711–719, 2008. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318176bfcd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamon E, Avellini B. Physiologic limits to work in the heat and evaporative coefficient for women. J Appl Physiol 41: 71–76, 1976. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.41.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamon E, Avellini B, Krajewski J. Physiological and biophysical limits to work in the heat for clothed men and women. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 44: 918–925, 1978. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.44.6.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenney WL, Lewis DA, Hyde DE, Dyksterhouse TS, Armstrong CG, Fowler SR, Williams DA. Physiologically derived critical evaporative coefficients for protective clothing ensembles. J Appl Physiol (1985) 63: 1095–1099, 1987. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.3.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenney WL, Zeman MJ. Psychrometric limits and critical evaporative coefficients for unacclimated men and women. J Appl Physiol 92: 2256–2263, 2002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01040.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf ST, Folkerts MA, Cottle RM, Daanen HAM, Kenney WL. Metabolism- and sex-dependent critical WBGT limits at rest and during exercise in the heat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 321: R295–R302, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00101.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belding HS, Hatch TF. Relation of skin temperature to acclimation and tolerance to heat. Fed Proc 22: 881–883, 1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dougherty KA, Chow M, Larry Kenney W. Critical environmental limits for exercising heat-acclimated lean and obese boys. Eur J Appl Physiol 108: 779–789, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenney WL. Psychrometric limits and critical evaporative coefficients for exercising older women. J Appl Physiol 129: 263–271, 2020. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00345.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonjer FJE. Actual energy expenditure in relation to the physical working capacity. Ergonomics 5: 29–31, 1962. doi: 10.1080/00140136208930549. 25988109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kenefick RW, Cheuvront SN. Hydration for recreational sport and physical activity. Nutr Rev 70: S137–S142, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O’Brien WL, Bassett DR Jr, Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, Jacobs DR Jr, Leon AS. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32: S498–S504, 2000. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das Gupta S, Bobbert M, Faber H, Kistemaker D. Metabolic cost in healthy fit older adults and young adults during overground and treadmill walking. Eur J Appl Physiol 121: 2787–2797, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00421-021-04740-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker FC, Waner JI, Vieira EF, Taylor SR, Driver HS, Mitchell D. Sleep and 24 hour body temperatures: a comparison in young men, naturally cycling women and women taking hormonal contraceptives. J Physiol 530: 565–574, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0565k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Notley SR, Meade RD, Kenny GP. Time following ingestion does not influence the validity of telemetry pill measurements of core temperature during exercise-heat stress: The journal Temperature toolbox. Temperature 8: 12–20, 2021. doi: 10.1080/23328940.2020.1801119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramanathan NL. A new weighting system for mean surface temperature of the human body. J Appl Physiol 19: 531–533, 1964. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cramer MN, Jay O. Partitional calorimetry. J Appl Physiol (1985) 126: 267–277, 2019. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00191.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jetté M, Sidney K, Blümchen G. Metabolic equivalents (METS) in exercise testing, exercise prescription, and evaluation of functional capacity. Clin Cardiol 13: 555–565, 1990. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960130809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernard TE, Caravello V, Schwartz SW, Ashley CD. WBGT clothing adjustment factors for four clothing ensembles and the effects of metabolic demands. J Occup Environ Hyg 5: 1–5, 2008. doi: 10.1080/15459620701732355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernard TE, Kenney WL. Rationale for a personal monitor for heat strain. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 55: 505–514, 1994. doi: 10.1080/15428119491018772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenney WL, Hyde DE, Bernard TE. Physiological evaluation of liquid-barrier, vapor-permeable protective clothing ensembles for work in hot environments. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 54: 397–402, 1993. doi: 10.1080/15298669391354865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenney WL, Lewis DA, Armstrong CG, Hyde DE, Dyksterhouse TS, Fowler SR, Williams DA. Psychrometric limits to prolonged work in protective clothing ensembles. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 49: 390–395, 1988. doi: 10.1080/15298668891379954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kolka MA, Stephenson LA. Interaction of menstrual cycle phase, clothing resistance and exercise on thermoregulation in women. J Therm Biol 22: 137–141, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4565(97)00003-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenney WL, Craighead DH, Alexander LM. Heat waves, aging, and human cardiovascular health. Med Sci Sports Exerc 46: 1891–1899, 2014. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenney WL, Wolf ST, Dillon GA, Berry CW, Alexander LM. Temperature regulation during exercise in the heat: insights for the aging athlete. J Sci Med Sport 24: 739–746, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2020.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis FP, Nelson F, Pincus L. Mortality during heat waves in New York City July, 1972 and August and September, 1973. Environ Res 10: 1–13, 1975. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(75)90069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semenza JC, McCullough JE, Flanders WD, McGeehin MA, Lumpkin JR. Excess hospital admissions during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. Am J Prev Med 16: 269–277, 1999. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]