Keywords: arousal, goal-directed behavior, neuronal activation, peripheral vasoconstriction, seeking behavior

Abstract

Proper inflow of oxygen into brain tissue is essential for maintaining normal neural functions. Although oxygen levels in the brain’s extracellular space depend upon a balance between its delivery from arterial blood and its metabolic consumption, the use of high-speed electrochemical detection revealed rapid increases in brain oxygen levels elicited by various salient sensory stimuli. These stimuli also increase intrabrain heat production, an index of metabolic neural activation, but these changes are slower and more prolonged than changes in oxygen levels. Therefore, under physiological conditions, the oxygen inflow into brain tissue exceeds its loss due to consumption, thus preventing any metabolic deficit. Here, we used oxygen sensors coupled with amperometry to examine the pattern of real-time oxygen fluctuations in the nucleus accumbens during glucose-drinking behavior in trained rats. Following the exposure to a glucose-containing cup, oxygen levels rapidly increased, peaked when the rat initiated drinking, and relatively decreased during consumption. Similar oxygen changes but more episodic drinking occurred when Stevia, a calorie-free sweet substance, was substituted for glucose. When water was substituted for glucose, rats tested the water but refused to consume all of it. Although the basic pattern of oxygen changes during this water test was similar to that with glucose drinking, the increases were larger. Finally, oxygen increases were significantly larger when rats were exposed to concealed glucose and made multiple unsuccessful attempts to obtain and consume it. Based on these data, we discuss the mechanisms underlying behavior-related brain oxygen fluctuations and their functional significance.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Oxygen sensors coupled with high-speed amperometry were used to examine brain oxygen fluctuations during glucose-drinking behavior in trained rats. Oxygen levels rapidly increased following presentation of a glucose-contained cup, peaking at the initiation of glucose drinking, and relatively decreasing during drinking. Oxygen increases were larger when rats were exposed to concealed glucose and made multiple attempts to obtain it. We discuss the mechanisms underlying behavior-related brain oxygen fluctuations and their functional significance.

INTRODUCTION

Proper entry of oxygen into brain tissue is essential for maintaining normal neural functions. Although brain oxygenation primarily depends on the efficiency of breathing and subsequent changes in blood oxygen levels, oxygen levels in the brain’s extracellular space also depend on the tone of brain vessels and changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF), which are regulated by neuronal activity. Development of high-resolution electrochemical techniques revealed that brain oxygen levels fluctuate under physiological conditions, showing relatively large increases (20%–50% over a quiet wakefulness baseline) induced by salient sensory stimuli of different nature and modality (1, 2). These increases occurred with the second-scale onset latencies preceding oxygen decreases in the subcutaneous space (1, 2). These physiological brain oxygen increases also preceded slower and more prolonged increases in brain-muscle temperature differentials, a measure of intrabrain heat production resulting from metabolic neural activation (3). Therefore, following neuronal activation, the brain is capable of rapid increases in its oxygenation levels to compensate for more delayed increases in oxygen consumption associated with metabolic neural activation.

Although the exposure to salient sensory stimuli is a useful method to examine physiological fluctuations in brain oxygenation and their underlying mechanisms, the pattern of oxygen fluctuations during motivated behavior remains unknown. To address this issue, we used oxygen sensors coupled with high-speed amperometry to examine the pattern of oxygen changes in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) during glucose-drinking behavior in trained rats. This technology can be successfully used in freely moving rats over multiple recording sessions, and it has second-scale temporal resolution, thus allowing to reveal the pattern of rapid oxygen fluctuations associated with critical behavioral events.

Our basic model utilized training, in which rats were exposed to a cup containing 3 mL of 15% glucose solution over several daily sessions. All subsequent oxygen recordings were conducted in rats trained to consume entire volume of presented glucose. First, we examined changes in NAc oxygen associated with the presentation of a glucose-filled cup, subsequent drinking behavior, and removal of the empty cup from the recording chamber. In addition to the main glucose-drinking tests, we also examined NAc oxygen dynamics during three additional tests. First, instead of glucose, rats were presented with a cup containing an equal amount of noncaloric sugar substitute (Stevia). In the second test, rats were presented with the same cup containing an equal amount of water. Finally, rats were presented with a cup containing glucose that was concealed with a clear jar, making the glucose inaccessible to the rat. Our goal was to elucidate patterns of brain oxygenation associated with different aspects of drinking behavior and its variants associated with either the change in the nature of the reinforcer (water vs. glucose and Stevia vs. glucose) or the animals’ inability to obtain expected glucose.

METHODS

Subjects

Twelve Long-Evans male rats (Taconic, Germantown, NY), weighing 400–460 g were used in this study. They were housed individually under a 12-h light cycle (lights on at 07:00), with food and water provided ad libitum. All procedures were performed in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication 865-23) and were approved by the National Institute on Drug Abuse–Intramural Research Program Animal Care and Use Committee. Maximal care was taken to minimize the number of experimental animals and any possible discomfort or suffering at all stages of the study.

Surgery

Surgical procedures for electrochemical assessment of oxygen have been described in detail elsewhere (4, 5). Briefly put, under general anesthesia (Equithesin, a mixture of sodium pentobarbital and chloral hydrate), rats were implanted with oxygen sensors (Model 7002-02; Pinnacle Technology, Inc., Lawrence, KS) targeting the medial segment of the NAc. The sensors were secured with dental acrylic to three stainless steel screws threaded into the skull. Rats were allowed a minimum of 5 days of postoperative recovery.

Electrochemical Detection of Oxygen

For in vivo oxygen detection, we used Pinnacle oxygen sensors coupled with high-speed amperometry. The principles of electrochemical oxygen detection, construction of oxygen sensors, and their calibration are described in detail elsewhere (4, 6). Pinnacle oxygen sensors consist of an epoxy-sheathed disk electrode that is ground to a fine surface using a diamond-lapping disk. These sensors are prepared from Pt-Ir wire 180 µm in diameter, with a sensing area of 0.025 mm2 at the tip. The active electrode is incorporated with an integrated Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Dissolved oxygen is reduced on the active surface of these sensors, which is held at a stable potential of −0.6 V versus the reference electrode. The current from the sensor is relayed to a computer via a potentiostat (Model 3104, Pinnacle Technology) and recorded at 1-s intervals, using PAL software utility (Version 1.5.0, Pinnacle Technology). Oxygen sensors were calibrated at 37°C by the manufacturer (Pinnacle Technology) according to a standard protocol described elsewhere (7); concentration curves were quantitatively analyzed in-house. During calibration, the sensors produced linear current changes with increases in oxygen concentrations within a range of physiological brain oxygen concentrations (0–30 μM). Substrate sensitivity of oxygen sensors determined as a mean of three 5 μM tests varied from 0.64 to 0.91 nA/1 μM. Oxygen sensors were also tested by the manufacturer for their selectivity toward electroactive substances such as dopamine (0.4 μM) and ascorbate (250 μM), none of which had significant effects on reduction current.

Experimental Procedures

All rats before surgeries were habituated in the environment of future recordings and trained to consume 3 mL of 15% solution of glucose presented in a plastic bottle cup fixed on a metal plate for stability. During training, the glucose-containing cup was presented for 1 h, and the procedure was repeated twice during the ∼6-h session. If the rats learned to consume the beverage eagerly and entirely, they were selected for surgery.

All tests occurred inside a Plexiglas chamber placed inside a sound- and light-attenuated plastic box under continuous weak red light (15 W). At the onset of each recording session, rats were briefly anesthetized (<2 min) with isoflurane, and the electrochemical sensors were connected to the potentiostat via an electrically shielded flexible cable and a multichannel electrical swivel. Testing began 90–120 min after the electrochemical sensors were connected to the recording instrument, allowing for baseline currents to stabilize. Electrochemical currents were recorded with a 1-s time resolution.

Each experimental rat underwent several recording sessions. During the first session, each rat was exposed to a similar basic testing protocol, which included two presentations of 15% glucose solution. After a 60–90-min habituation period and stabilization of electrochemical currents, a glucose-containing cup was presented to rats, resulting with some onset latency in drinking behavior. The empty cup was removed from the cage 1 h after its presentation. The same procedure was repeated in the afternoon, 2 h after the first glucose presentation. Each behavioral event, such as the cup introduction, cup removal, start of drinking, and end of drinking, was marked for future analyses. The cup was placed in the same location independently of the animal’s location in the chamber, thus allowing visual observation of animal behavior.

During subsequent sessions, each rat was presented in stochastic order with the two tests: one with the glucose-cup presentation and other with one of three additional tests. First, instead of glucose, the rat received the same cup containing 3 mL of 7.0% solution of the product prepared from Stevia extract (Tate & Lyne; distributed by Walmart). This is a calorie-free sugar substitute (sweetener), and its concentration was adjusted to equal sensory properties (sweetness) of 15% glucose solution used in this study. Information on the relative sweetness of Stevia product with respect to glucose was obtained from Stevia producers. These data were obtained in humans; no data for rats were found. In the second additional test, instead of glucose, the rat was presented with a cup containing an equal amount of water (3 mL). Finally, in the third additional test, the rat was presented with a cup containing glucose, which was tightly covered by a glass jar. Despite the ability to see and smell the presented object, the rat was unable to obtain glucose despite intense interaction with the jar.

Histology and Data Analysis

When experiments were complete, rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated, and their brains were extracted and stored in 10% formalin solution. Later, the brains were cut and analyzed for verification of the locations of cerebral implants and possible tissue damage at the area of electrochemical recording.

Electrochemical data were sampled with 1-s time resolution and analyzed with 1-min and 4-s resolution. Data were presented as both absolute and relative changes with respect to the moment of cup presentation, cup removal, and key behavioral events (start and end of drinking). One-way ANOVA with repeated measures, followed by post hoc Fisher tests, was used for statistical evaluation of changes in oxygen levels preceding and following the defined behavioral events. Between-group differences in oxygen dynamics (regular glucose tests vs. each of three unusual tests) were also assessed using a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA.

RESULTS

Data Sample

Data shown in this study were obtained in six rats during 34 daily sessions. We conducted 29 glucose trials and 23 additional trials. Of those additional trials, eight were water trials, seven were Stevia trials, and eight were concealed glucose trials (total n = 52 tests). The location of recording sensors in the medial segment of the NAc was confirmed histologically, as described in anatomical atlas of rat brain by Paxinos and Watson (8).

Global Changes in NAc Oxygen during Glucose-Drinking Behavior

All rats included in this data sample showed consistent glucose-drinking behavior during each experimental session. In most of the tests (n = 23/29), rats began to drink with relatively small latencies (6–100 s) and consumed the entire 3 mL of glucose within one drinking episode. Six tests, in which drinking began with atypically large latencies (4–5 min) or glucose was consumed in two or three drinking episodes, were excluded from current analysis.

In all glucose tests (n = 23 in 6 rats), rats initiated drinking, but its latencies varied between 6 and 92 s with a mean of 38.2 ± 6.4 s (SD = 30.8 s). The duration of drinking also varied from 73 s to 201 s with a mean of 110.7 ± 6.2 s (SD = 29.5 s).

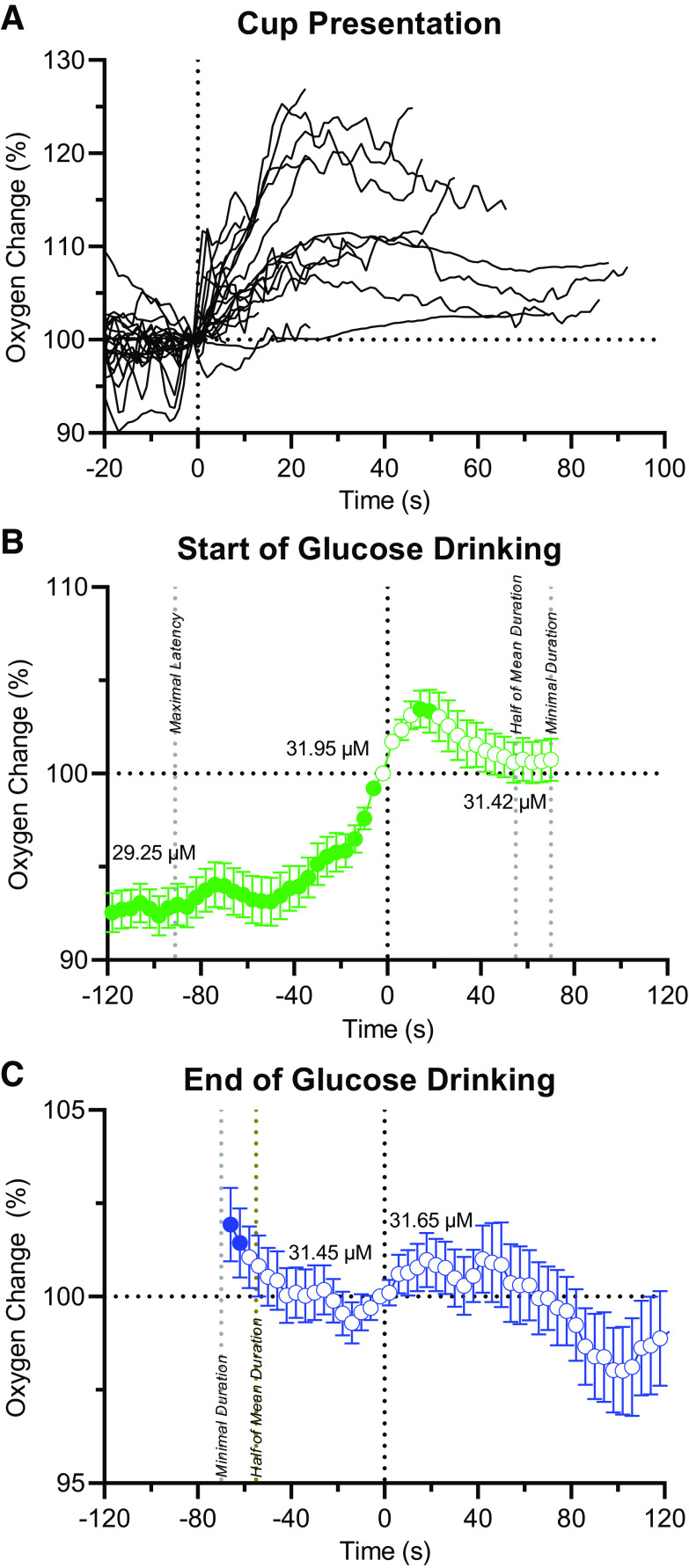

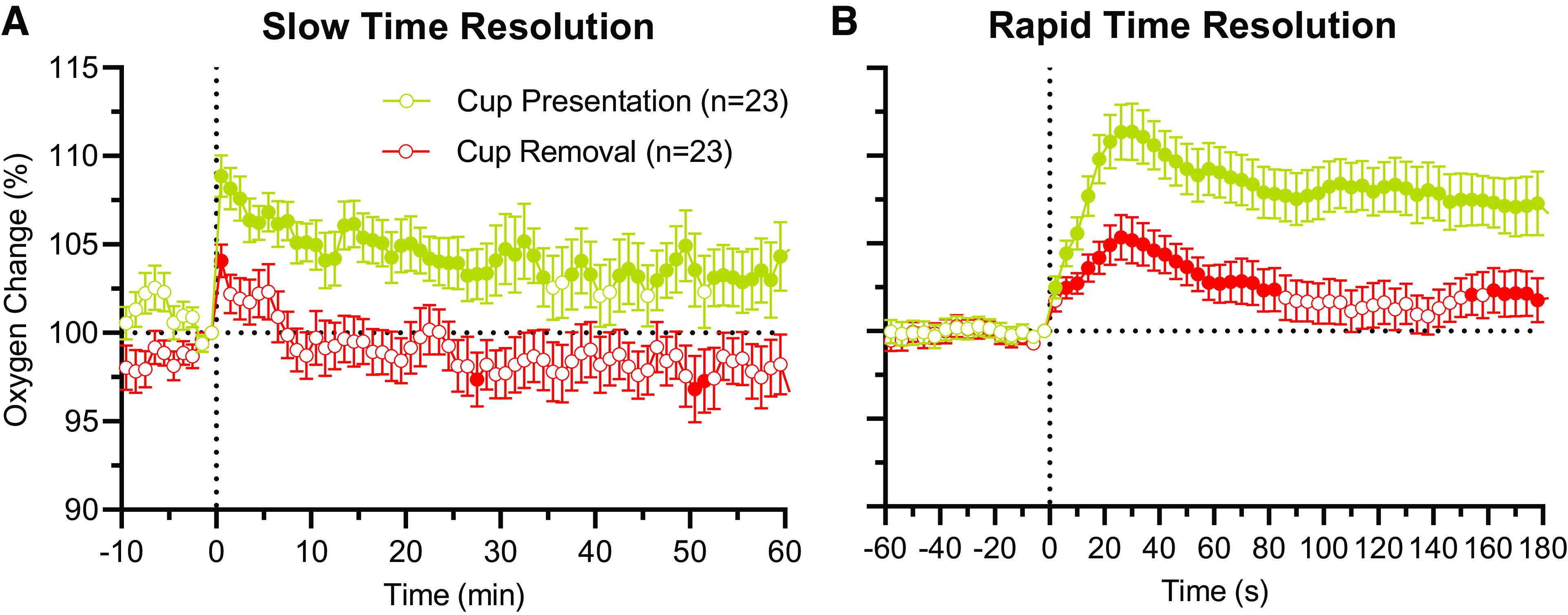

First, we examined mean changes in NAc oxygen levels following presentation of a glucose-containing cup with subsequent drinking behavior (Fig. 1A). As these data were obtained in multiple sessions and basal values of reduction currents varied, data are shown as a percent change, with 100% set for baselines. Figure 1A also shows oxygen changes for an hour following the removal of an empty cup when all rats completed drinking and were in sleep-like behavior. NAc oxygen levels rapidly increased in both situations (F22,1,540 = 3.92 and F22,1,540 = 2.13; both P < 0.001), but the increase following full cup presentation was significantly larger than that for an empty cup removal (108.9 ± 1.2% vs. 104.1 ± 0.9% at peak, respectively; t = 3.2; P < 0.01). The increase was evident for the entire hour after a full cup presentation, but it was only significant for a couple of minutes after empty cup removal. Despite differences in response amplitude and duration, in both cases, the increase was very rapid and oxygen levels peaked during the first minute postevent. Between-test differences in oxygen dynamics were confirmed by using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures (Stimulus × Time Interaction: F1,44 = 9.19, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Mean (±SE) changes in nucleus accumbens (NAc) oxygen levels following the presentation of a glucose-containing cup with subsequent drinking and removal of an empty cup. Data were analyzed with slow, 1-min (A) and rapid, 4-s time resolution (B), and they are shown in percent with 100% set as preevent baseline. n = number of averaged tests. Filled symbols show values significantly different from preevent 1-min baseline (P < 0.05). Quantitative results of statistical evaluations (ANOVA’s F values) are shown in the text.

For a more accurate representation of oxygen dynamics, the same data were analyzed with rapid (4-s bin) time resolution for the first 3 min postevent (Fig. 1B). In this case, we found that NAc oxygen began increasing almost instantly following full cup presentation, reaching significance during the first time-bin (0–4 s). Although smaller in amplitude, the increase following an empty cup removal was also equally rapid, with similarly short onset latencies and similar times to peaks. Between-group differences in oxygen dynamics were confirmed by using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures (Stimulus × Time Interaction: F1,44 = 12.95, P < 0.001); these differences were significant in all time points except the first one.

Phasic Changes during Glucose-Drinking Behavior

As both the latency to initiate drinking and the duration of drinking varied, we first analyzed NAc oxygen changes before and after three critical behavioral events: presentation of a full cup, initiation of drinking, and cessation of drinking. Then, these three data sets were combined to represent the entire dynamics of NAc oxygen fluctuations during glucose-drinking behavior.

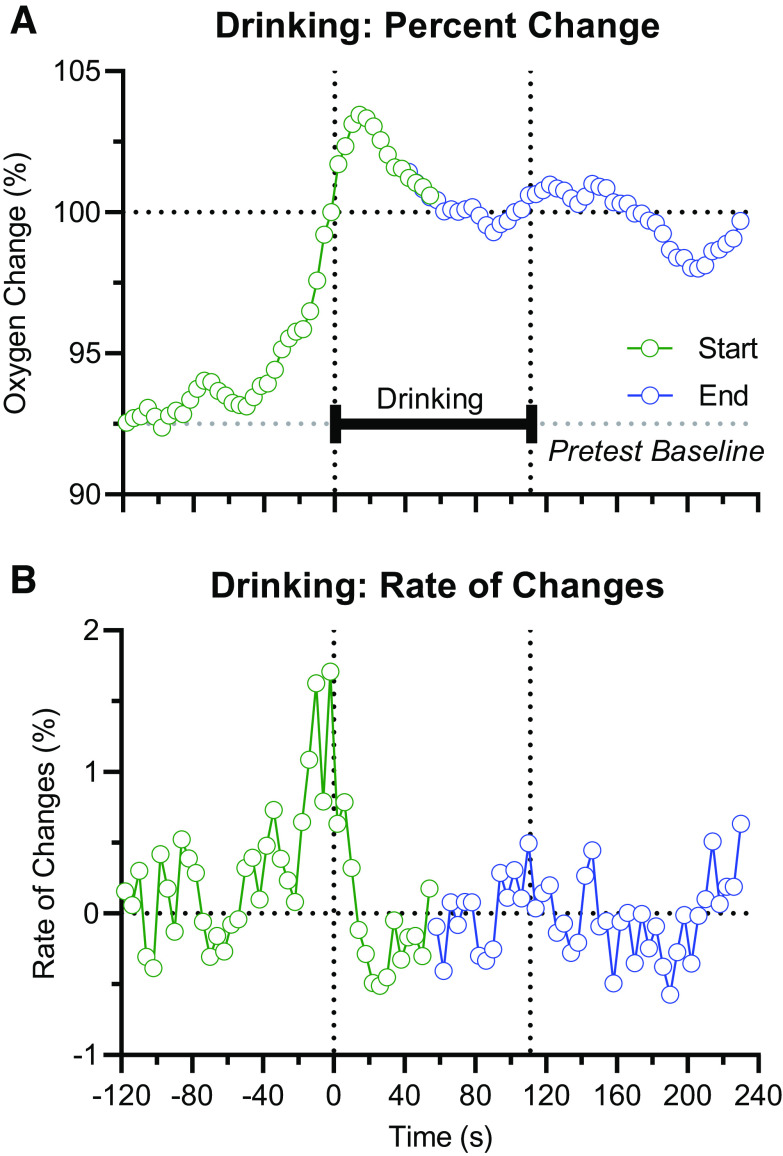

Figure 2A shows original records of individual changes in NAc oxygen levels after presentation of a full cup until the start of drinking shown with 1-s time resolution. As can be seen, drinking began at different time intervals after cup presentation, and oxygen levels in most cases (18/20) increased to a different extent (2%–26% above baseline). In some cases, drinking began at peak levels, but in several cases with longer latencies, drinking began when oxygen levels slightly decreased after their picks. For the mean, drinking began when NAc oxygen levels increased on average ∼9% (or ∼2.7 µM) above the preevent baseline.

Figure 2.

Changes in nucleus accumbens (NAc) oxygen levels associated with three critical events of glucose-drinking behavior. A: individual changes in oxygen levels after the presentation of a glucose-filled cup until the rats initiated drinking behavior. B: mean (±SE) changes before and after the initiation of glucose drinking (0 s). Filled symbols show values significantly different from preevent baseline (100%). C: mean (±SE) changes before and after the end of glucose drinking (0 s). Filled symbols show values significantly different from a preevent baseline (100%). Both graphs (B and C) show time intervals of maximal latency, half-duration of glucose drinking, and absolute values of oxygen levels at these time intervals. Quantitative results of statistical evaluations (ANOVA’s F values) are shown in the text.

Figure 2B shows mean changes of NAc oxygen levels preceding and following the initiation of drinking. In this case, the last 4-s value before the start of drinking was set as 100%, and changes were statistically evaluated in both directions (before and after initiation of drinking). The data preceding the start of drinking are shown for 120 s covering the maximal latency to initiate drinking (92 s), whereas data following the start of drinking are shown for minimal duration of drinking (73 s). Following this analysis, we found that NAc oxygen levels significantly and gradually increased preceding the start of drinking (F22,660 = 15.51, P < 0.001). The increase continued for ∼16 s after the start of drinking but then began to decrease to the levels close to what were observed at the start of drinking (F22,396 = 3.47, P < 0.001).

Figure 2C shows changes preceding and following the end of drinking. In this case, the last 4-s value at the end of drinking was set as 100%, and changes in oxygen were analyzed both before (72 s corresponding to minimal drinking duration) and after (120 s) this event. As can be seen, NAc oxygen levels slowly decrease during drinking (F22,374 = 3.01, P < 0.001) and stabilize at levels (31.65 µM) very similar to the levels at the start of drinking (31.95 µM). These levels did not change significantly after the end of drinking despite increased locomotor activity and repeated bouts of licking of an empty cup.

Figure 3 represents the entire dynamics of oxygen fluctuations associated with glucose-drinking behavior. As the duration of drinking varied from 73 to 201 s (mean = 111 s), changes in oxygen for a half of mean duration of drinking (55 s) both after the start of drinking and before its end were used to assess drinking-associated oxygen dynamics. As we used relative changes in percent, with a value of 100% for both the start and end of drinking, data were adjusted for the mean values of absolute oxygen levels. We also calculated the rate of changes as differences between consecutive 4-s values. As can be seen in Fig. 3A, NAc oxygen levels strongly increased after presentation of glucose-filled cup before the initiation of drinking. Although oxygen levels continue to increase for ∼16 s after the drinking start, rate of changes, which strongly increased preceding drinking start, dropped rapidly at the drinking start, slightly decreased during drinking, and remained at stable levels thereafter.

Figure 3.

Schematic of changes in nucleus accumbens (NAc) oxygen levels during glucose-drinking behavior. Changes in NAc oxygen levels (A) and rate of their changes (B) preceding the start of drinking, during drinking, and after its end. The value at the last minute before the start of drinking is set as 100%.

Tonic and Phasic Changes following Substitution of Stevia for Glucose

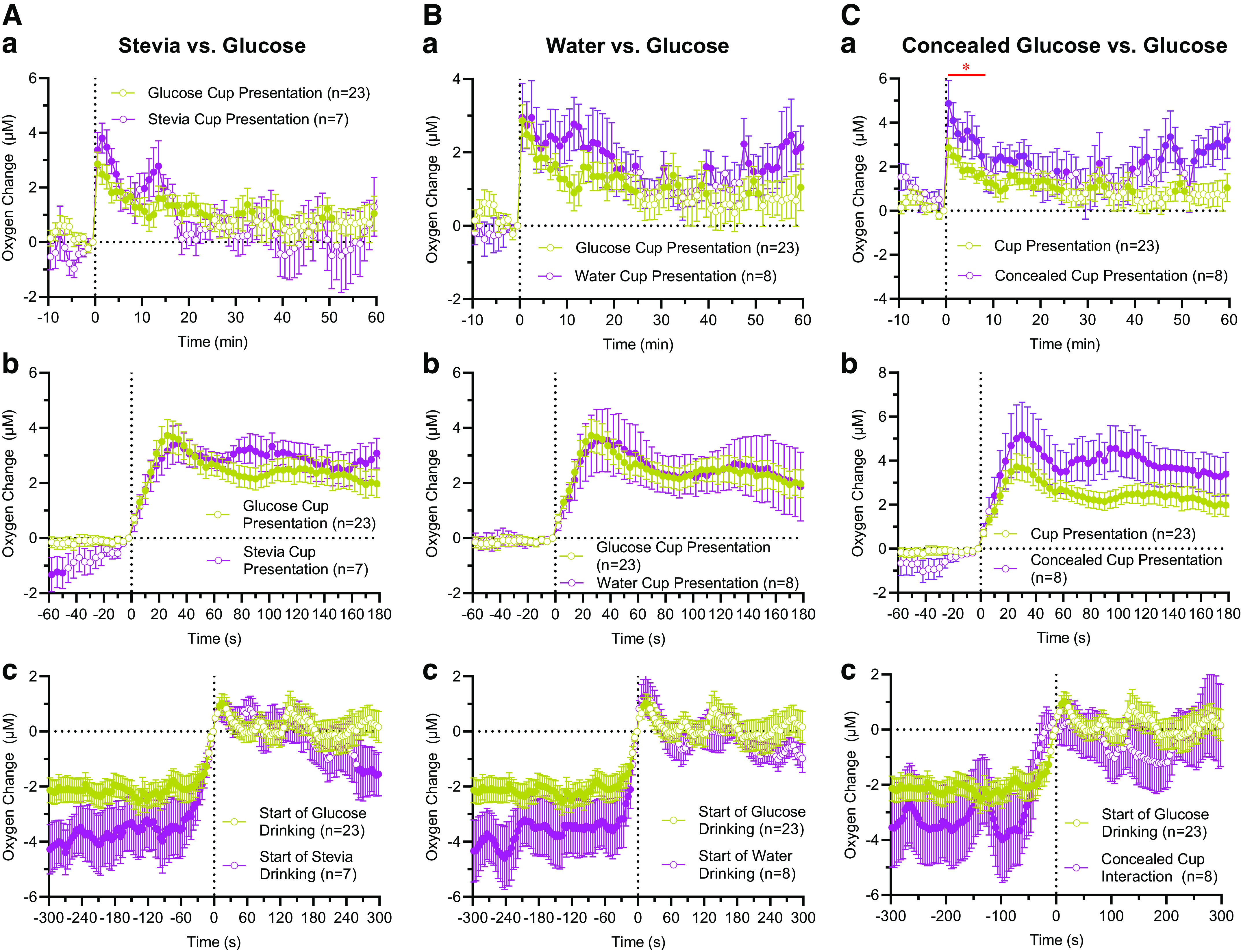

When Stevia, an equally sweet solution, was substituted for glucose, the rats quickly tasted the content of the cup. The latency to initiate drinking varied from 10 to 92 s, with a mean (49.4 ± 26.1 s) similar to that seen in glucose tests. However, drinking patterns were different with several drinking episodes, and full consumption in a single episode was seen in only one of seven tests.

The pattern of oxygen fluctuations in this test was very similar to that of glucose (Fig. 4A). Although the increases in most individual data points were larger in the Stevia group for the first 14 min, the difference within this interval was not significant (F1,28 = 1.61, P = 0.21). A larger between-curve difference was seen during the first 5 min after the Stevia-cup presentation when rats initially tasted this solution. However, this difference was also not significant (F1,28 = 1.92, P = 0.17). Similar to the main glucose test, NAc oxygen levels began to increase after the Stevia cup was presented to rats, and the levels picked up at the start of drinking and increased but were relatively stable during repeated tasting and drinking of the Stevia solution (Fig. 4Ac).

Figure 4.

Changes in nucleus accumbens (NAc) oxygen levels associated with three additional tests (A: substitution of Stevia for glucose; B: substitution of water for glucose; C: presentation of a glucose-containing cup, with glucose unavailable). In each graph, data for regular glucose drinking are shown for comparison. Top line (a) = mean (±SE) changes analyzed with slow time resolution, middle line (b) = mean (±SE) changes analyzed with rapid time resolution, and bottom line (c) = mean (±SE) changes preceding and following the initiation of Stevia and water drinking. In Cc, zero time = start of active interaction with the jar vs. start of drinking, and red line with asterisk shows show a time interval of significant between-group differences. Filled symbols in each graph show values significantly different from preevent baseline (P < 0.05). n = number of averaged tests. Quantitative results of statistical evaluations (ANOVA’s F values) are shown in the text.

Tonic and Phasic Changes during Substitution of Water for Glucose

When the rats were presented with the cup containing 3 mL of water, all rats tasted the content of the cup with highly variable latencies (6–405 s), but only in one of eight tests did the rat consume the entire content of the cup. In all other cases, rats drank a small portion of water in several drinking episodes, consuming less than half of the water volume in an hour.

As shown in Fig. 4Ba, changes in NAc oxygen with water substitution were very similar to those with regular glucose drinking, but the increase with water tasting was somewhat stronger. Although between-group difference was not significant for the first 20 min after water-cup presentation (F1,29 = 1.36, P = 0.25), tendency for increase was found between 6 and 12 min poststimulus (F1,29 = 2.71, P < 0.11), the time interval when most rats consumed water in several drinking episodes. In this case, rapid time resolution did not reveal any between-group differences for the initial 3 min following water-cup presentation (Fig. 4Bb). When the data were analyzed with respect to the start of water testing, oxygen increases preceding water tasting were larger than oxygen increases preceding glucose drinking (Fig. 4Bc). The change following the start of tasting was similar in both groups.

Tonic and Phasic Changes during Sustained Glucose-Seeking Behavior (Concealed Glucose)

When the rat was presented with a glucose-containing cup covered by a glass jar, it began to scratch and lick the jar with variable latencies (6–92 s; mean = 31.9 ± 8.9 s), which were similar to the latencies of drinking start in the main test. Enhanced activity continued for up to 6–10 min and then the rat ceased seeking, slowly moving into sleep-like behavior.

Figure 4C shows mean changes in NAc oxygen levels during this test. Data for regular tests with glucose consumption (from Fig. 1A) are shown for comparison. As can be seen, NAc oxygen levels during this test showed similar dynamics as the test with regular glucose drinking, but the increase was larger in most data points. The use of two-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed that two curves differ significantly for 8 min following cup presentation (F1,29 = 4.92, P = 0.035); this time interval covers both the latency and duration of drinking in one group and intense interaction with the jar in another group. Despite a much smaller group size, NAc oxygen levels were larger for the entire hour after concealed glucose, but this difference had only a statistical tendency (F1,29 = 2.69 P = 0.11). Larger oxygen increases were also evident with concealed glucose when data were analyzed with high temporal resolution (Fig. 4Cb).

Minor differences were found when data were analyzed with respect to the moment of the first physical interaction with the cup-containing jar (Fig. 4Cc). Similar to the main test, NAc oxygen levels strongly increased before the first interaction with the glass jar and peaked at the start of drinking. In contrast to the drinking test, oxygen levels during interaction with the jar remained relatively stable for ∼60 s after the start of interaction. In this case, oxygen levels also peaked just before the rat began to interact with the jar.

DISCUSSION

Our previous studies with high-speed electrochemical assessments of physiological fluctuations in brain oxygen levels revealed that this parameter is dynamic, showing rapid increases following exposure to salient sensory stimuli (2, 4, 6). To extend this line of research, here we examined how oxygen levels in the brain’s extracellular space fluctuate during a simple variant of learned behavior in trained rats. Specifically, we examined the pattern of oxygen changes associated with different aspects of free glucose-drinking behavior and its variants associated with the change in the nature of the reinforcer (water vs. glucose and Stevia vs. glucose) or the animal’s inability to obtain desired glucose (concealed glucose). Similar to our previous studies, NAc, a critical structure for sensorimotor integration and a key component of the motivation-reinforcement circuit (9, 10), has been chosen as a structure to represent the general pattern of behavior-associated changes in brain oxygenation.

Model of Motivated Drinking Behavior

Glucose can be viewed from two sides. From one side, it is the essential substance for an organism’s metabolic activity and its proper delivery to the brain is critical for normal functioning of the nervous system. On the other side, glucose is a reinforcer; animals and humans consume glucose-containing products for their sweet taste. As confirmed in this study, naive rats quickly learn to consume 15% solution of glucose after a relatively short (3–5 days) passive training. Therefore, glucose solution acts as a positive reinforcer, and our behavioral paradigm could be viewed as the simplest model of motivated behavior. In contrast to food or water, which act as state-dependent reinforcers inducing eating or drinking in food- or water-deprived conditions, glucose drinking is maintained without food or water deprivation, suggesting that the reinforcing properties of glucose are independent of deprivation state. As shown here, rats trained to consume glucose quickly began to drink Stevia solution, which presumably has a similar sweet taste, but the pattern of drinking in most tests was different from consumption of glucose solution. Therefore, despite sweet taste, Stevia solution has slightly different sensory effects, which are rapidly recognized by glucose-experienced rats. Water is a classic natural reinforcer in water-deprived conditions, but rats that expected to obtain glucose rapidly tasted water but refused to consume it in any significant amount.

Sensory Stimulation and Arousal as Essential Forces for Initiation of Drinking Behavior

Presentation of a glucose-containing cup to a trained rat results in a rapid increase in NAc oxygen levels that is accelerated preceding the start of drinking, maintained during drinking, and lingered at enhanced levels for an hour after the end of drinking. Although oxygen levels slightly increased for ∼16 s after the start of drinking, the rate of oxygen increase reached maximum during the last minute preceding drinking initiation. The same accelerated oxygen increases also occurred when the usual content of the cup was substituted to water or Stevia, resulting in tasting of these liquids within a similar range of onset latencies. As these changes not only followed a stimulus presentation but also preceded the initiation of drinking, they could be viewed as a component of searching behavior that results in all three tests in initiation of drinking. Similar gradual oxygen increases also occurred when the rats were exposed to concealed glucose, reaching maximum just before and during active interaction with the jar that prevents direct contact with glucose.

However, the removal of the empty cup (i.e., a simple arousing stimulus without behavioral consequences) also increased oxygen levels. Although the magnitude of this increase was significantly smaller than that with glucose-cup presentation, in both cases, the increase was equally rapid, peaking at ∼30 s poststimulus, the timing when the rat began to drink glucose from the glucose-filled cup. As shown in our previous studies (2, 4, 6), similarly rapid brain oxygen increases occurred in naive rats exposed to various salient or arousing somatosensory stimuli (auditory stimulus, tail pinch, placement in a new cage, social interaction with another animal, etc.). Therefore, generalized neuronal activation (arousal) elicited by salient sensory stimuli could be viewed as both a precondition for and a correlate of seeking aspects of motivated behavior, which is accompanied by increased oxygen entry into brain tissue.

Glucose-Drinking Behavior

Although NAc oxygen levels gradually increased preceding the start of glucose drinking, their dynamics rapidly changed when drinking began. The oxygen levels still slightly increased, but the rate of increase rapidly declined, and oxygen levels fell relative to their values at the start of drinking. If the predrinking oxygen increase results from neural activation, this relative decrease in oxygen levels can suggest that glucose consumption is associated with rapid cessation of preceding neural activation. On the contrary, if consumption of glucose in experienced rats is viewed as “reward,” this abrupt cessation of preceding activation could be viewed as its neural correlate. The same change could also be viewed as a correlate of the consummatory phase of motivated behavior, which follows its activation-related seeking phase.

This pattern of oxygen dynamics is consistent with electrophysiological findings, which revealed both phasic activation of accumbal neurons induced by reward-predicting sensory cues and tonic decreases in neuronal activity during drinking (11–15). A similar pattern of changes was also found in our thermorecording studies during eating behavior in trained rats (16). In this case, NAc-muscle differential, a measure of intrabrain heat production, rapidly increased preceding the start of food consumption and relatively decreased during eating. In contrast, skin-muscle differential, a measure of peripheral vascular tone, rapidly decreased following presentation of food pellets and additionally decreased during food consumption. The latter change, suggesting strong peripheral vasoconstriction, can be the primary factor determining increases in brain and body temperatures during feeding behavior.

Although less evident, NAc levels additionally increased at the end of drinking when the rat made numerous attempts to interact with an empty cup (see Fig. 2C). The postconsumption licking of an empty cup made it difficult to define the exact moment when drinking ended. Therefore, the second peak of postconsumption oxygen increase could be related to the reappearance of glucose-seeking activity. Our previous experiments with drinking behavior revealed that trained rats are able to consume much larger volumes of glucose (17), suggesting that the presented 3-mL sample is unable to satisfy them fully.

Sustained seeking activity also occurred when rats were presented with concealed glucose and made multiple unsuccessful attempts to reach the content of the cup. During this period, NAc oxygen levels additionally increased above the levels seen during glucose drinking. Therefore, it appears that the inability to obtain expected glucose (or satisfy existing motivation, no reward) is associated with sustained neural activation and larger oxygen increase that manifest at the behavioral level as a continuous searching activity.

In addition to relatively small phasic fluctuations in oxygen levels before and during drinking, oxygen levels only slowly decreased toward baseline after the end of glucose consumption (see Fig. 1). This tonic increase contrasts more phasic oxygen response following empty cup removal. Although the exact mechanisms underlying this tonic effect remain unclear, it may result from the central effects of consumed glucose after its delivery into brain tissue. More time is necessary for glucose to be absorbed, interact with receptor sites, and directly affect brain activity. Our previous data with electrochemical assessments of brain glucose revealed 3–4-min delay between the start of glucose drinking or its intragastric delivery and the detection of glucose in the brain’s extracellular space (18).

Possible Mechanisms Determining Behavior-Related Fluctuations in Brain Oxygen Levels

As shown in this study, glucose-drinking behavior is accompanied by increases in NAc oxygen levels that began after presentation of glucose-containing cup, peaked at the start of glucose consumption, slightly decreased during drinking, and maintained for a longer time after consumption was ended. Two primary factors can be responsible for this pattern of oxygen response. The first factor is the direct neural effects on cerebral vessels (neurovascular coupling) that result in their dilation, increased CBF, and enhanced entry of oxygen and glucose into the brain’s extracellular space (19–21). Although it is usually hypothesized that these effects are triggered by neuronal activation, our knowledge on the mechanisms linking neuronal and vascular effects is limited. Furthermore, data on the patterns of behavior-associated neuronal activity are also limited, and it is not yet clear which aspect of neuronal activation, the increase in electrical (spiking) or metabolic activity, makes a primary contribution to vascular effects.

The second factor affecting the pattern of brain oxygen response is redistribution of arterial blood from the skin and some internal organs to the brain due to peripheral vasoconstriction, the known centrally mediated effect elicited by salient sensory stimuli (22–24). This effect is rapid, strong, and relatively long term, resulting in global increases in CBF and greatly contributing to the enhancement and prolongation of brain oxygen increases. Intrabrain entry of oxygen also depends on density of vascularization of brain tissue, which appears to be dense in most gray-matter limbic structures. This factor may determine similarity of oxygen responses in different brain structures despite differences in neuronal impulse activity. To address this issue of structural specificity, we previously examined the effects of the same arousing stimuli on changes in oxygen and glucose levels in two distantly located brain structures: the NAc and substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr), which have profound differences in impulse activity (2, 25). Although most accumbal neurons are silent or have slow, sporadic spiking activity quiet wakefulness, they are phasically excited by arousing stimuli and during motor activity (26–28). In contrast, SNr neurons are tonically autoactive, showing high discharge rate and transient excitations and inhibitions following sensory stimulation (29–32). Despite these differences, the pattern of both oxygen and glucose responses in these two structures was similar and both concentration curves tightly correlated, suggesting a common neural trigger for both responses. Therefore, similar to increases in CBF found in different brain structures following exposure to various arousing or stressful stimuli (33, 34), brain oxygen increases appear to be a generalized, arousal-related phenomenon occurring in the brain as a whole. However, consistent with the presumed differences in impulse activity, oxygen responses in the SNr were more tonic with weaker concentration increases. Although silent sensory stimuli also enhance breathing (35), affecting blood oxygen levels, this concentration-dependent effect is slow and its role in rapid fluctuations in brain oxygen increases appears to be limited.

Hence, the pattern of behavior-associated oxygen response is clearly adaptive to precede later occurring increases in oxygen consumption during metabolic neural activation and to prevent a possible metabolic deficit. Some statements presented in this study remain hypothetical and others some can be viewed as speculative due to absence of direct data. Further studies using different techniques and new approaches will be necessary to verify and clarify our findings.

GRANTS

The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH Grant 1ZIADA000566-10 to E. A. Kiyatkin).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.A.K. conceived and designed research; C.M.C. and E.A.K. performed experiments; C.M.C., M.R.I., and E.A.K. analyzed data; C.M.C., M.R.I., and E.A.K. interpreted results of experiments; C.M.C. prepared figures; E.A.K. drafted manuscript; C.M.C. and M.R.I. edited and revised manuscript; C.M.C., M.R.I., and E.A.K. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kiyatkin EA. Central and peripheral mechanisms underlying physiological and drug-induced fluctuations in brain oxygen in freely-moving rats. Front Integr Neurosci 12: 44, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2018.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas SA, Curay CM, Kiyatkin EA. Relationships between oxygen changes in the brain and periphery following physiological activation and the actions of heroin and cocaine. Sci Rep 11: 6355, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85798-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiyatkin EA. Brain temperature: from physiology and pharmacology to neuropathology. Handb Clin Neurol 157: 483–504, 2018. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-64074-1.00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solis E Jr, Cameron-Burr KT, Kiyatkin EA. Rapid physiological fluctuations in nucleus accumbens oxygen levels induced by arousing stimuli: relationships with changes in brain glucose and metabolic brain activation. Front Integr Neurosci 11: 9, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2017.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solis E Jr, Cameron-Burr KT, Shaham Y, Kiyatkin EA. Intravenous heroin induces rapid brain hypoxia and hyperglycemia that precede brain metabolic response. eNeuro 4: ENEURO.0151-17.2017, 2017. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0151-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiyatkin EA. Physiological and drug-induced fluctuations in brain oxygen and glucose assessed by substrate-selective sensors coupled with high-speed amperiomentry. In: Compendium of in Vivo Monitoring in Real Time. edited by Wilson GA, Michael AC.. Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific, 2019, vol. 3, p. 219–250. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolger FB, Bennett R, Lowry JP. An in vitro characterisation comparing carbon paste and Pt microelectrodes for real-time detection of brain tissue oxygen. Analyst 136: 4028–4035, 2011. doi: 10.1039/c1an15324b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paxinos J, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Sydney: Academic Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mogenson GJ, Jones DL, Yim CY. From motivation to action: functional interface between the limbic system and the motor system. Prog Neurobiol 14: 69–97, 1980. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(80)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wise RA, Bozarth MA. A psychomotor stimulant theory of addiction. Psychol Rev 94: 469–492, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicola SM, Yun IA, Wakabayashi KT, Fields HL. Cue-evoked firing of nucleus accumbens neurons encodes motivational significance during a discriminative stimulus task. J Neurophysiol 91: 1840–1865, 2004. doi: 10.1152/jn.00657.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicola SM, Yun IA, Wakabayashi KT, Fields HL. Firing of nucleus accumbens neurons during the consummatory phase of a discriminative stimulus task depends on previous reward predictive cues. J Neurophysiol 91: 1866–1882, 2004. doi: 10.1152/jn.00658.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roitman MF, Wheeler RA, Carelli RM. Nucleus accumbens neurons are innately tuned for rewarding and aversive taste stimuli, encode their predictors, and are linked to motor output. Neuron 45: 587–597, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taha SA, Fields HL. Encoding of palatability and appetitive behaviors by distinct neuronal populations in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci 25: 1193–1202, 2005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3975-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krause M, German PW, Taha SA, Fields HL. A pause in nucleus accumbens neuron firing is required to initiate and maintain feeding. J Neurosci 30: 4746–4756, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0197-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smirnov MS, Kiyatkin EA. Fluctuations in central and peripheral temperatures associated with feeding behavior in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1415–R1424, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90636.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakabayashi KT, Myal SE, Kiyatkin EA. Fluctuations in nucleus accumbens extracellular glutamate and glucose during motivated glucose-drinking behavior: dissecting the neurochemistry of reward. J Neurochem 132: 327–341, 2015. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wakabayashi KT, Kiyatkin EA. Behavior-associated and post-consumption glucose entry into the nucleus accumbens extracellular space during glucose free-drinking in trained rats. Front Behav Neurosci 9: 173, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Attwell D, Buchan AM, Charpak S, Lauritzen M, Macvicar BA, Newman EA. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature 468: 232–243, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nature09613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lecrux C, Hamel E. The neurovascular unit in brain function and disease. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 203: 47–59, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muoio V, Persson PB, Sendeski MM. The neurovascular unit—concept review. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 210: 790–798, 2014. doi: 10.1111/apha.12250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altschule MD. Emotion and the circulation. Circulation 3: 444–454, 1951. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.3.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomon GF, Moos RH, Stone GC, Fessel WJ. Peripheral vasoconstriction induced by emotional stress in rats. Angiology 15: 362–365, 1964. doi: 10.1177/000331976401500806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker MA, Cronin MJ, Mountjoy DG. Variability of skin temperature in the waking monkey. Am J Physiol 230: 449–455, 1976. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.2.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiyatkin EA, Lenoir M. Rapid fluctuations in extracellular brain glucose levels induced by natural arousing stimuli and intravenous cocaine: fueling the brain during neural activation. J Neurophysiol 108: 1669–1684, 2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.00521.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carelli RM, West MO. Representation of the body by single neurons in the dorsolateral striatum of the awake, unrestrained rats. J Comp Neurol 309: 231–249, 1991. doi: 10.1002/cne.903090205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiyatkin EA, Rebec GV. Modulation of striatal neuronal activity by glutamate and GABA: iontophoresis in awake, unrestrained rats. Brain Res 822: 88–106, 1999. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rebec GV. Behavioral electrophysiology of psychostimulants. Neuropsychopharmacology 31: 2341–2348, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schultz W. Activity of pars reticulata neurons of monkey substantia nigra in relation to motor, sensory, and complex events. J Neurophysiol 55: 660–677, 1986. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.4.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarz M, Sontag KH, Wand P. Sensory-motor processing in substantia nigra pars reticulata in conscious cats. J Physiol 347: 129–147, 1984. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishino H, Ono T, Fukuda M, Sasaki K. Monkey substantia nigra (pars reticulata) neuron discharges during operant feeding. Brain Res 334: 190–193, 1985. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90587-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Windels F, Kiyatkin EA. GABAergic mechanisms in regulating the activity state of substantia nigra pars reticulata neurons. Neuroscience 140: 1289–1299, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryan RM. Cerebral blood flow and energy metabolism during stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 259: H269–H280, 1990. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.2.H269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Özbay PS, Chang C, Picchioni D, Mandelkow H, Chappel-Farley MG, van Gelderen P, de Zwart JA, Duyn J. Sympathetic activity contributes to the fMRI signal. Commun Biol 2: 421, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kabir MM, Beig MI, Baumert M, Trombini M, Mastorci F, Sgoifo A, Walker FR, Day TA, Nalivaiko E. Respiratory pattern in awake rats: effects of motor activity and of alerting stimuli. Physiol Behav 101: 22–31, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]