Abstract

This study aimed to explore clinician roles and experiences related to the implementation and sustainability of coordinated specialty care (CSC) programs for first episode psychosis. Qualitative interviews were conducted with 20 CSC providers and team members, recruited from five CSC programs. Using a semi-structured guide, interviews explored experiences with the delivery of CSC in the context of community-based outpatient mental health agencies and the challenges with implementation. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using thematic analysis. Themes were parsed into two overarching categories, provider, and organizational-level factors, and further distilled into subthemes which interacted with one another to form an interacting web of barriers to successful programmatic implementation for CSC programs. Study findings have important implications for development of future policy for financing mental health agencies, the creation of additional materials, supports for the model, and hiring and retention of staff for future implemented CSC programs.

Keywords: Coordinated specialty care, First episode psychosis, Implementation, Providers, Qualitative

Introduction

In the U.S., early intervention for first episode psychosis (FEP) comes in the form of coordinated specialty care (CSC) and utilizes a multidisciplinary team to deliver psychotherapy, supported education and employment, case management, family education and support, and low dose antipsychotic medication (Mueser et al., 2015; Wright et al., 2019). Findings from Recovery After An Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) studies and the real-world implementation of CSC in various states have demonstrated the improvement of psychiatric and functional outcomes following involvement in CSC among individuals with FEP (Bello et al., 2017; Kane et al., 2016; Oluwoye et al., 2020). Supported by federal funding (e.g., mental health block grant, Early Psychosis Intervention Network), CSC programs in the U.S. have proliferated to 114 programs in 36 states with the number only continuing to expand in the past five years (“Coordinated Specialty Care in First Episode of Psychosis Could Improve Outcomes Long Term,” 2017). Although CSC programs continue to propagate, implementation of CSC remains relatively understudied (Durlak & DuPre, 2008).

Implementation research points to characteristics at the community-, provider- and organizational-level that are important to understanding whether components of a program are administered as intended and whether the integration of a program occurred effectively (Dixon & Patel, 2020; Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Lobb & Colditz, 2013; Nilsen, 2015). Previous studies identified that at the program- or organizational-level, staffing, caseload, climate, and financial sustainability are key to understanding the implementation of evidence-based programs in mental health agencies and potential modifications to implementation strategies used to integrate the program and components of program (Aarons et al., 2012; Belling et al., 2011; Hoge et al., 2013; Mancini et al., 2009). Specific to CSC, several barriers have been identified to impact the expansion of CSC in the U.S., these include financing, workforce development (i.e., training for providers), and community activation (i.e., outreach and referrals) (Dixon, 2017). Yet, there are relatively few studies that have sought to understand and address these barriers in a systematic way in order to improve the implementation of CSC (Powell et al., 2021). Of the limited research in this area, results have focused primarily on organizational-level characteristics (e.g., financial sustainability) and have largely used quantitative methods through the use of process data (Bao et al., 2021; Mascayano et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2019).

To address this gap in current literature, the present study utilized qualitative methods to further our understanding of facilitators and barriers to implementing CSC in community-based mental health agencies. Given that CSC providers are positioned to engage with clients, the broader community, and administrators, this qualitative study explored provider experiences and perspectives on community, provider, and program/organizational- level factors related to the implementation of CSC.

Methods

Setting

Providers from five CSC programs implemented in outpatient mental health agencies in the Pacific Northwest, U.S., were asked to participate in semi-structured interviews. Of the five CSC programs, three were located in urban areas and two were located in rural-serving communities. As described elsewhere, CSC team members consist of a multidisciplinary team that generally includes a program director, a supported employment and education specialist, an individual therapist, a family therapist, a medical provider, and a case manager to deliver the multiple components included in a CSC model (Oluwoye et al., 2020). Furthermore, all CSC programs participate in initial onboarding training to support implementation and continuous technical assistance which includes monthly Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) sessions (e.g., individual tele-education, and case consultations with implementation experts) and monthly outcome monitoring and data quality meetings. The current study was part of a larger program evaluation study and approved by the Washington State Institutional Review Board.

Participants

A purposeful sampling approach was used, as CSC providers would provide specific in-depth information about the implementation of CSC within their agency, as well as provide perspective of interacting with service users and mental health administrators (Palinkas et al., 2015). Eligibility criteria was limited to providers who were ≥ age of 18 and those who had been employed and provided services through CSC for ≥ 2 months. The two-month cut off was designated to ensure providers both completed their position training and engaged with clients for at least one month prior to the interview. To recruit providers from CSC programs, research staff emailed details of the study to providers employed at the five CSC program. Separate follow up meetings were held with program directors to provide an additional overview of the study’s purpose and answer questions in an effort to encourage additional team members to participate in the study. Newly hired team members were also informed of the study and pre-scheduled for an interview within 2–3 months of employment start date. Participant recruitment occurred from August 2017 through December 2019.

Procedures

Telephone-based interviews were conducted with participants using a semi-structured interview guide. Interview questions with participants were centered on implementation, sustainability, and program improvement. For example, participants were asked questions including: “Which aspects of the program have been most difficult to implement,” “Are there additional program needs which you believe the current program does not address?” and “Can you think of any additional trainings which you would need to be successful?” Participants were prompted for more information when appropriate to ensure breadth and depth of responses. The average duration of interviews was 41 min. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim, with all identifying information removed to maintain participant confidentiality.

Qualitative Analyses

A thematic analysis approach was used to analyze the transcribed data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The four authors independently reviewed and coded transcripts line by line using open coding to generate general key concepts, for example negative program implementation, stigma, and community outreach. To enhance rigor and reduce bias, the first, third, and fourth authors, two with experience of working with CSC and a social work researcher, met to develop an initial coding scheme and subsequent meetings were used to refine the codebook for the remaining transcripts, which were coded by the first two authors (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). Transcripts were then imported into NVivo 12, a qualitative software used to assist in the organization of qualitative data, and recoded (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018). The first two authors met regularly to discuss codes, and along with the fourth author major themes were identified and exemplar quotes were identified and used to illustrate themes.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 20 CSC providers were recruited and participated in telephone-based interviews. The mean age of participants was 36.80 (SD = 12.95; range 24–60 years) and most participants were female (n = 12, 60%). Most participants were non-Hispanic white (n = 8; 40%), six (30%) participants identified as Hispanic, one (5%) participant identified as Asian, and five chose not to identify their race or ethnicity. While participants represented various roles in CSC, most participants were supported education and employment specialists (n = 6; 30%), followed by program directors (n = 5; 25%), individual therapists (n = 5; 25%), medication providers (n = 2; 10%), case manager (n = 1; 5%) and family therapist (n = 1; 5%). Of the 20 participants, four (20%) served in dual positions, which generally consisted of some combination of program director and family or individual therapist. On average participants had 13.80 months (SD = 12.30) of experience working within a CSC program. Based on the geographical location of CSC programs, 35% (n = 7) of providers were located in rural communities.

Barriers and Facilitators to Program Implementation

Findings revealed that factors or characteristics that impacted implementation of CSC in community-based outpatient mental health agencies could be categorized into two overarching themes: provider-level, and organizational-level.

Provider–Staff Level Factors

Service Delivery

Several participants expressed concerns about self-efficacy, specifically their ability to successfully perform duties related to their roles in the program. Barriers to self-efficacy included competing expectations between the CSC program and the larger mental health agency (e.g., number of public, private, and uninsured clients accepted into the program given capacity limits), the ability to accomplish goals given the workload, and time spent traveling due to geographical limitations, as noted by one Supported Education and Employment Specialist:

“Some of the barriers, in my role anyway, is finding that balance between being able to get out and see employers and build rapport with them as well as being available for my clients that might need a little bit more help and need to meet with them twice a week rather than once a week.” (Supported Education and Employment Specialist, Site 1)

Participants shared positive sentiments about the comprehensiveness of the treatment modules, though they noted a lack of services or treatment modules focused on substance use. Several participants mentioned that a substance use dedicated role in CSC would significantly improve services. Many participants also stated that the vocational services (i.e., supported education and employment) were the easiest services to implement and were often used to engage clients. Participants noted that this was likely because education and employment needs often preceded treatment needs and were consequently less stigmatized than other CSC services that were more mental health focused. Consequently, this engagement and rapport building allowed for them to link clients to other services offered and increase overall client engagement. To further support families and improve the family engagement, participants recommended the inclusion of a family peer advocate. Overall, participants indicated that flexibility in both professional roles and treatment components better facilitated CSC service delivery and better supported client need. Some components, however, were perceived to be more challenging and as contributing to client disengagement. For example, one participant noted that the program’s emphasis on recovery and resilience and timing at times does not necessarily allow for rapport building especially upon entry into the program when a client may not be at that stage.

“Using the model can be a bit challenging sometimes especially because you want to be able to build rapport and going right off the bat with talking about recovery and resilience doesn’t work for a lot of people and that’s how its set up, and that’s kind of challenging.” (Individual Therapist, Site 2)

Demands on Time

Participants noted that balancing workload and expectations against the time to complete assigned duties within a workday or week was challenging. Participants mentioned the expectations at the larger network programmatic level (i.e., measurement delivery, data entry) were time consuming and considered participation in routine outcome monitoring and overarching evaluation as research and beyond their scope of work as providers soley focused on treatment delivery.

“Tracking every phone call, every in-person contact, every appointment throughout the entire team for every client every week, that’s really hard to keep up with. ‘Cause I have to go through all our psych consult things and – or all our EHR stuff and yeah, it’s pretty time consuming some of it.” (Individual Therapist, Site 1)

While mobility and service provision in the community as opposed to merely in office can be perceived as a strength of CSC, it also impacts time for service delivery. Participants cited travel time as reducing both the amount of time they had to deliver direct services and the number of clients they served in day. Clients served, however, did benefit from lengthy car rides during which providers and clients could develop stronger therapeutic alliance and build rapport.

“The hard part with New Journeys (CSC) is it’s a lot of driving. A lot of transportation that is needed….so that can be like 4 hours of time that I’m blocked out to complete that task. And that, that’s hard when I’m like held to a standard of direct service hours for my other side of the program… [but] I love driving clients. That’s the one thing I found also is that rapport building during that time is phenomenal” (Case Manager, Site 2)

Training and Continuous Consultation

Participants described the initial trainings, which include role specific trainings and measurement and data quality, as being effective in preparing them to implement the program. They also found utility in continued monthly trainings with the implementation research team.

“[The ECHO clinics and monthly director consultations are] a good chance to, one, just kind of be able to communicate with the other teams like a whole team. And you know, they provide an education piece as a part of the ECHO clinic and then we do case review. It’s definitely helpful to be able to hear what other people are doing in their area and the challenges they’ve had and what they’ve done to try and overcome them. And to get input from other people about other options or attempts. You know? So those are probably the two best supportive consultation training things we have going on, for me at least.” (Program Director/Family Therapist/Individual Therapist, Site 4)

Participants indicated trainings facilitated program success, though they desired additional trainings at both the community and provider levels. At a community-level, participants mentioned additional training on how to better present psychosis to various community organizations and how to engage hard-to-reach populations. At the provider-level, participants spoke about their own self-care and strategies to mitigate burnout. Other trainings which participants felt would be beneficial included a training focused on connecting clients to benefits such as food stamps, housing, and insurance.

Organizational-Level Factors

Referrals

Creating networks for referrals with other community-based organizations was considered necessary, but also presented challenges. Obtaining referrals was described as one of the most difficult aspects to starting and sustaining a program. A contributing factor to receiving referrals were other agencies’, organizations’, and community members’ abilities to identify those who may be experiencing psychosis. Participants talked about the importance of increasing awareness of the services that CSC provides and educating the community about psychosis:

“Getting the word out that the program exists and getting the referrals – getting appropriate referrals, has required a lot of work and going out to all different kinds of agencies, inpatient facilities, law enforcements, schools and other pediatricians, psychiatrists, and even the different departments in our own agency. Then there’s this turnover of staff, so having to go back out there again, and again, and again.” (Program Director/Family Therapist, Site 2)

Organizational Climate

Cross-disciplinary collaboration was considered one of the more significant benefits of working in a CSC program. Participants stated the team-based approach was essential when determining diagnoses and working in challenging situations. Monthly videoconference meetings between programmatic roles across the CSC program network provided participants the opportunity to engage with providers in similar roles at other agencies. Participants highlighted that this enabled more team-oriented work, both within their own agency and among professional peers who are working toward similar goals. Furthermore, the team approach allowed for a deeper understanding of each of the clients and their individual needs which many felt improved the care provided.

“That is something that I’ve always really appreciated, and I’ve really missed in – you don’t get that kind of teamwork in – even in community health in general care. And so, I really appreciated getting to be a part of the team and working like that. And I do feel like I get to know my clients so much better because we have the team approach and because we do our team meetings. We’re always talking to each other about what’s happening. It gives me a richer understanding of the clients” (Medical Staff, Site 3)

Hiring and Retaining Providers

Challenges with hiring individuals differentiated depending on the position posted. Program directors who generally led hiring efforts discussed their high standards for roles (e.g., peer specialists) and the desire to find the ‘right fit,’ which contributed to prolonged hiring processes. Furthermore, the number of applicants for positions varied depending upon the role. For instance, there was a dearth of applicants for more clinical roles such as the individual and family therapist as compared to a wealth of applicants for paraprofessional roles. These clinical roles were consequently not always filled in timely manners.

“This type of position – outreach with the most chronically ill – is not a position most clinicians want to do. It took me three months to hire for the IRT and Family Therapist roles” (Program Director, Site 3)

Several participants noted that possible reasons for the limited number of applicants included a hesitancy of applicants to work with individuals experiencing psychosis and an inability to offer a more competitive salary and benefits package due to fiscal constraints. After the initial delay in hiring for CSC roles, participants also indicated that both the stress of working in community mental health and misconceptions about positions and their related duties lead to high turnover rates for CSC programs. The difficulties contributing to adequate staffing also impacted providers currently employed by CSC programs, who were charged with multiple roles on the teams until the position could be filled.

“I think as a team we’ve sometimes struggled with recruitment of staff. It can be really difficult to find team members who are experienced and have the level of experience that we want for working with this population and also have interest and drive and that are willing to do it for the amount of money that the agency will offer them, which I think can be really tough.” (Medical Provider, Site 3)

Several participants believed that there needed to be a reevaluation of the requirements for program roles to increase the number of applicants for program roles and mitigate staff turnover. They suggested that reducing educational requirements from graduate level to undergraduate level degrees for certain positions (e.g., individual therapist) would increase the number of applicants and that the salary and benefits package would be more amenable for entry-level providers. To prevent staff turnover participants suggested reducing the number of meetings, providing shorter meetings at the start and end of the week, and setting boundaries between work and home.

Financial Sustainability

Participants spoke to a myriad of long-term financial difficulties when considering the sustainability of CSC at their mental health agencies. Such difficulties were largely attributed to billing for services:

“The cost of services is really – it’s been a lot. And, you know, Medicaid doesn’t cover all the costs, even for our fifty percent. And so the other fifty percent that we can’t bill insurance for, the grant doesn’t fully cover either, so our agency has to eat the cost”. (Program Director, Site 3)

Several participants went on to discuss deviations from how CSC was originally structurally implemented in an effort to make the program more financially viable. These deviations or adaptions included limiting the number of providers on teams by having existing providers serve in dual roles and shared responsibilities. A few participants also noted that the cost of CSC services is also high for clients with private insurance, which can make the services unsustainable for those clients given number of necessary sessions as well as the cost of medication.

Multidirectional Relationship Between Themes

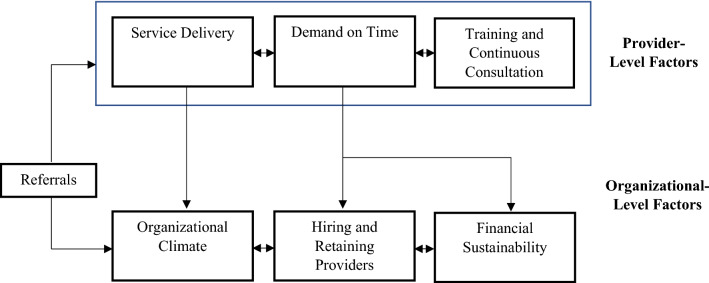

Figure 1 displays the conceptual representation of themes (i.e., provider- and organizational-level) and subthemes (e.g., service delivery, referrals) that emerged from qualitative findings and were considered essential to the implementation CSC programs. In addition to representation of themes, Fig. 1 highlights the interrelationship of provider and organizational-level factors and how some of these factors are unidirectional and others bidirectional within and between themes. For instance, among the factors identified at the provider-level, participants described that the demands on time were due to service delivery (e.g., time spent traveling due to geographical limitations) and participation in program training and continuous consultation. At the organizational level, hiring and retaining providers was often cited as difficult due financial constraints and the ability to offer competitive pay. Whereas cross-disciplinary collaboration within organizational climate was considered a facilitator to retaining team members. Participants discussed how the demands on their time could result in burnout, which created organizational difficulties in hiring and retaining providers, and created concerns about the financial sustainability of the model, which is an example of the interrelationship between provider- and organizational-level factors.

Fig. 1.

Framework of provider–and organizational-level factors that influence implementation of CSC in community-based mental health agencies

Discussion

The present study offers qualitative findings on provider perspectives and experiences with implementing CSC in community-based outpatient mental health agencies and contributes to the limited research specifically focused on the implementation of CSC in the U.S. As seen in Fig. 1, the major themes identified provide insight into barriers at the provider-, program-, organizational-level that hinder the widespread implementation of CSC in the U.S., while also identifying ways in which programs have made adaptions to address challenges with implementation.

Participants scored the importance as well as the difficulty of receiving referrals to sustain a program, educating the community about psychosis to reduce societal stigma, and bringing awareness about services offered through CSC, signifying overlap of both provider- and organizational-level factors. These findings further highlight how the concept of outreach in implementation research is pivotal to providing equitable services and creating a partnership with community leaders and organizations that link potential clients to CSC. Difficulties with both of these elements has the potential to contribute to the lack of diversity in caseload and impact sustainability of the program due to lack of referrals (Baumann & Cabassa, 2020; Dixon & Patel, 2020). To address the challenges with engaging the community, additional training on strategies and content that could be used to engage and build awareness with diverse and underserved communities were expressed by participants. Moreover, our findings also underscore the importance of discrete and multifaceted implementation strategies that provides continuous support to CSC programs. Participants revealed the need for such strategies that are low burden on providers and include interactions with other providers and content matter experts (e.g., ECHO), trainings that increase knowledge (e.g., community resources) and skills (e.g., delivery psychotherapy components, facilitating community presentations).

At the provider-level, the challenges and need for training to address high rates of substance use among individuals with FEP was also a point of concern, which is consistent with prior research (Oluwoye & Fraser, 2021; Oluwoye et al., 2019). The CSC model used in the five programs that participated in the present study includes a substance use module focused on harm reduction in the individual therapy component of the program. While CSC has become the standard of care for early psychosis, there remains an unmet need for additional research on evidence-based interventions for substance use within the context of CSC, as well as understanding what implementation strategies are needed to incorporate and sustain such interventions at the provider and organizational level. Similar to other mental health programs, understaffing, provider burnout, and high turnover rate were cited as organizational-level barriers (Belling et al., 2011; Hoge et al., 2013; Mancini et al., 2009). Lack of team members due to hiring or retention difficulties, subsequently placed additional demands on participants. Interestingly, the reevaluation of requirements for employment has the potential to mitigate financial concerns by lowering the salary costs associated with specific roles and while also increasing the number applicants for open positions, yet, there may be concerns about the limited experience and entry level of reducing educational requirements for some roles. It is also important to note that the sentiments expressed may not be new to CSC programs, as bachelors level individual therapist have been used in other programs (Browne et al., 2016). Several participants performed the duties of multiple team roles above and beyond the role they were originally hired into. Recognizing that the mental health field has a high turnover rate, CSC should incorporate cross-over training for each of the providers at orientation to potentially increase self-efficacy. However, this organizational-level adaptation may come at cost to the delivery of CSC services, provider burnout, and turnover. The incorporation of cross-over training for providers to potentially increase self-efficacy will not address these funding and billing limitations of these programs and the choices to not hire additional needed staff to mitigate those costs.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted when considering study findings. The sample recruited included participants from one state and thus shared experiences and insights into delivering one type of CSC model. Although at the time of this study only two CSC programs had peer specialists, the sample for the present study did not include all roles within CSC (e.g., peer specialists), which may have shed additional insight. While participants were recruited from one network of CSC programs, we recruited participants from five different mental health agencies in various geographical locations (e.g., rural, urban). As such the themes identified may not be generalizable to other CSC models or behavioral health settings. While the sample size may be considered relatively small in terms of qualitative studies, it is consistent with previous research with providers in mental health settings (Bao et al., 2021). Lastly, the present study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and since then many CSC programs have adjusted how services are delivered in effort to provide safe and equitable care (e.g., telehealth services). Understanding the transition to telehealth and remote services and the impact on program implementation should be explored in subsequent studies.

Conclusions

This study provides a qualitative perspective to a quantitative dominated question of barriers to implementation of CSC programs. It provides valuable insights to those who may be contemplating implementing a CSC program as well as informs the direction of further model development, training, and research. Through the continued effort to solicit feedback from the practitioners of CSC programs we can develop richer, more fulfilling, programs which reduce the challenges on clinicians, and improve the lives of clients, families, and the wellbeing of communities.

Funding

Dr. Oluwoye is supported by funding provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH117457).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bryony Stokes, Email: bryony.mueller@wsu.edu.

Elizabeth Fraser, Email: elizabeth.fraser@wsu.edu.

Liat Kriegel, Email: liat.kriegel@wsu.edu.

Oladunni Oluwoye, Email: oladunni.oluwoye@wsu.edu.

References

- Aarons GA, Glisson C, Green PD, Hoagwood K, Kelleher KJ, Landsverk JA, The Research Network on Youth Mental Health The organizational social context of mental health services and clinician attitudes toward evidence-based practice: A United States national study. Implementation Science. 2012;7(1):56. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Papp MA, Lee R, Shern D, Dixon LB. Financing early psychosis intervention programs: Provider organization perspectives. Psychiatric Services. 2021 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ. Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Services Research. 2020;20(1):190. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4975-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belling R, Whittock M, McLaren S, Burns T, Catty J, Jones IR, Rose D, Wykes T, The ECHO Group Achieving continuity of care: Facilitators and barriers in community mental health teams. Implementation Science. 2011;6(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello I, Lee R, Malinovsky I, Watkins L, Nossel I, Smith T, Ngo H, Birnbaum M, Marino L, Sederer LI, Radigan M, Gu G, Essock S, Dixon LB. OnTrackNY: The development of a coordinated specialty care program for individuals experiencing early psychosis. Psychiatric Services. 2017;68(4):318–320. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browne J, Edwards AN, Penn DL, Meyer-Kalos PS, Gottlieb JD, Julian P, Ludwig K, Mueser KT, Kane JM. Factor structure of therapist fidelity to individual resiliency training in the recovery after an initial schizophrenia episode early treatment program. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2016;12(6):1052–1063. doi: 10.1111/eip.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coordinated specialty care in first episode of psychosis could improve outcomes long term. (2017). The Brown University Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology Update, 19(1), 3–4. 10.1002/cpu.30183

- Dixon L. What it will take to make coordinated specialty care available to anyone experiencing early schizophrenia: getting over the hump. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(1):7. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Patel S. The application of implementation science to community mental health. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):173–174. doi: 10.1002/wps.20731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3–4):327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge MA, Stuart GW, Morris J, Flaherty MT, Paris M, Goplerud E. Mental health and addiction workforce development: Federal leadership is needed to address the growing crisis. Health Affairs. 2013;32(11):2005–2012. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Mueser KT, Penn DL, Rosenheck RA, Addington J, Brunette MF, Correll CU, Estroff SE, Marcy P, Robinson J, Meyer-Kalos PS, Gottlieb JD, Glynn SM, Lynde DW, Pipes R, Kurian BT, Miller AL, Heinssen RK. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-Year outcomes from the NIMH raise early treatment program. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362–372. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobb R, Colditz GA. Implementation science and its application to population health. Annual Review of Public Health. 2013;34(1):235–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini AD, Moser LL, Whitley R, McHugo GJ, Bond GR, Finnerty MT, Burns BJ. Assertive community treatment: Facilitators and barriers to implementation in routine mental health settings. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(2):189–195. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascayano F, Nossel I, Bello I, Smith T, Ngo H, Piscitelli S, Malinovsky I, Susser E, Dixon L. Understanding the implementation of coordinated specialty care for early psychosis in New York state: A guide using the RE-AIM framework. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2019;13(3):715–719. doi: 10.1111/eip.12782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Penn DL, Addington J, Brunette MF, Gingerich S, Glynn SM, Lynde DW, Gottlieb JD, Meyer-Kalos P, McGurk SR, Cather C, Saade S, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Rosenheck RA, Kane JM. The NAVIGATE program for first-episode psychosis: Rationale, overview, and description of psychosocial components. Psychiatric Services. 2015;66(7):680–690. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwoye O, Fraser E. Barriers and facilitators that influence providers’ ability to educate, monitor, and treat substance use in first-episode psychosis programs using the theoretical domains framework. Qualitative Health Research. 2021 doi: 10.1177/1049732321993443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwoye O, Monroe-DeVita M, Burduli E, Chwastiak L, McPherson S, McClellan JM, McDonell MG. Impact of tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use on treatment outcomes among patients experiencing first episode psychosis: Data from the national RAISE-ETP study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2019;13(1):142–146. doi: 10.1111/eip.12542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwoye O, Reneau H, Stokes B, Daughtry R, Venuto E, Sunbury T, Hong G, Lucenko B, Stiles B, McPherson SM, Kopelovich S, Monroe-DeVita M, McDonell MG. Preliminary evaluation of Washington State’s early intervention program for first-episode psychosis. Psychiatric Services. 2020;71(3):228–235. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2015;42(5):533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell A-L, Hinger C, Marshall-Lee ED, Miller-Roberts T, Phillips K. Implementing coordinated specialty care for first episode psychosis: A review of barriers and solutions. Community Mental Health Journal. 2021;57(2):268–276. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00644-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVivo (Version 12). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Smith TE, Kurk M, Sawhney R, Bao Y, Nossel I, Cohen DE, Dixon LB. Estimated staff time effort, costs, and medicaid revenues for coordinated specialty care clinics serving clients with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatric Services. 2019;70(5):425–427. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait L, Birchwood M, Trower P. Predicting engagement with services for psychosis: Insight, symptoms and recovery style. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182(2):123–128. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright A, Browne J, Mueser KT, Cather C. Evidence-based psychosocial treatment for individuals with early psychosis. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics. 2019;29(1):211–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2019.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]