Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the online teaching experiences of preservice teachers during the pandemic. Due to COVID-19, preservice teachers were required to work with children and families remotely to gain practicum experiences. Three preservice teachers’ work (family reflection papers, lesson reflection papers, video recordings of teaching, eBooks, and teaching movies) from two courses were analyzed using constant comparative analysis. The study findings indicated that preservice teachers struggled with maintaining children’s active engagement and identifying appropriate time to scaffold children’s learning since they could not observe the learning process of the children. However, they were able to overcome the challenges by employing different strategies (modeling, child-centered approach, and patience), with these attempts reflecting their pedagogical resilience.

Keywords: Early childhood education, Experiential learning, Online teaching, Preservice teachers, Resilience, Teacher education

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a worldwide impact on individuals in various ways, including teacher education, in particular. Due to this, many universities and schools have had to rapidly adapt to online teaching to create learning environments and prepare future teachers (Flores & Gago, 2020). This abrupt transition requires both teacher educators and preservice teachers to adapt to new models of teaching environments, and this process also results in several challenges and constraints that need to be overcome (Carrillo & Flores, 2020).

Previous research regarding online teaching in teacher preparation programs has been widely conducted to study the impact of online teaching, the factors that influence preservice teachers’ professional growth, the challenges associated with poor online teaching substructure, the inexperience of teachers, lack of information and resources, complex home environments, and lack of mentoring and support (e.g., Huber & Helm, 2020; Judd et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). However, many of these studies are oriented toward exploring the delivery of online teaching by teacher educators to student teachers and a lack of research focused on preservice teachers’ use of online teaching while working with young children in the field of early childhood education (ECE). Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the online teaching experiences of preservice teachers during the pandemic, guided by two research questions:

What challenges did preservice teachers confront when teaching remotely?

What strategies did preservice teachers use to overcome these challenges?

Online Teaching in Early Childhood Education

During the pandemic, numerous teacher education programs switched to online instruction to continue training prospective teachers to meet the prerequisites for teacher licensing. Due to the closure of many early childcare centers, preservice teachers were unable to be placed in classrooms with children, and consequently lacked opportunities to fulfill their practicum requirements. Nevertheless, the rapid development of online teaching (Hill, 2021) created educational opportunities for preservice teachers to continue interacting with children due to its convenience in terms of time, place, pace of learning, and financial costs (Khurana, 2016). When dealing with young children, synchronous face-to-face online teaching, in particular, must be integrated to approximate the social, cognitive, and teaching presence of learning in classrooms. This modality of teaching also necessitates preservice teachers to be adaptable and flexible to a range of instructional designs, as well as to improve practice and delivery methods (Garrison, 2000).

Instruction can be classified as content, process, and product (Tomlinson, 1999). Tomlinson noted that the product of instruction is equivalent to the learning outcome of the children, and is strongly dependent on the content and process. The focus of content needs to be within children’s zones of proximal development so that the content can be challenging but manageable for the children to learn without feeling helpless or overwhelmed (Hill, 2021; Vygotsky, 1978). As Tomlinson reiterated, teachers expect the children to learn from a particular segment of an activity that also reflects children’s developmental progress, readiness, interests, and learning profiles. A learning profile was described as the various methods by which children learn, whereas, the instructional process requires the flexibility of teachers to apply a wide range of activities, strategies, and techniques to better support children’s meaning making. For example, instruction can be structured from simple to complicated and from concrete to abstract (Brown, 2001; Greeno et al., 1996; Gagne, 1985). Expert teachers, as Berliner (1986) and Stronge (2002) elucidated, may employ a variety of instructional strategies based on their understanding of learners’ needs and the nature of active learning. Because of this complexity, a flexible instructional process might still be challenging for many novice teachers. Although online teaching is not a new concept in education, it is still a novel teaching modality in the ECE field. Judd et al. (2020) reported that only 34% of 699 in-service teachers in the U.S. reported prior online teaching professional development experiences, indicating that online teaching is still a new form for many teachers. Furthermore, there is widespread concern about the quality of online learning, as well as challenges in fostering social learning and engagement (Chen, 2010; O’Doherty et al., 2018). For preservice teachers who are still in the process of learning and have limited teaching experiences, online teaching provides an additional set of challenges (Hill, 2021); therefore, they need more support to adapt to this new teaching modality.

Teachers’ Resilience

Teaching is demanding labor because it demands the physical, intellectual, and socio-emotional abilities of teachers on a consistent basis throughout each day. This sustained effort and drain of over laboring, contributes to teachers’ stress and burnout (Mansfield, 2020). Teacher resilience is characterized as the capacity to bounce back and regain one’s strength and spirit quickly and effectively from challenges and maintain the motivation to teach (Sammons et al., 2007). Challenges include not just severe adversity but also the persistent incidents that occur daily and are ongoing, such as excessive workloads, time demands, and unsupportive school administrations, for example (Beltman et al., 2011; Gu & Day, 2013; Kelly et al., 2018; Masten & Powell, 2003). The nature and difficulty of challenges vary depending on the situation and over time (Bobek, 2002), and because of this, the ability to be resilient demands teachers to employ various strategies to adjust to different situations and overcome challenges. Resonating with the study purpose, preservice teachers’ use of strategies to overcome the challenges of online teaching is treated as resilience.

For more than a decade, resilience has been explored, and its potential benefits on teachers’ motivation, well-being, efficacy, and commitment widely acknowledged across countries (e.g., Day & Gu, 2014; Day & Hong, 2016; Hong, 2012; Mansfield et al., 2016). In particular, it is perceived as a critical non-cognitive attribute of novice teachers (Klassen et al., 2018). Ungar reported that resilience involves “both the capacity of individuals to navigate their way to the psychological, social, cultural, and physical resources that sustain their well-being, and their capacity individually and collectively to negotiate for these resources to be provided in culturally meaningful ways” (2012, p. 17).

It is suggested that a teacher education program that assists preservice teachers in resolving challenges encountered in their teaching, reflecting, and problem-solving can better prepare them to adapt to in-service teaching (Yost, 2006). Preservice teachers reported their satisfaction in learning and teaching from their practicum experiences, which reinforces their personal and professional development (Kaldi, 2009). As Tait elucidated, “working with scenarios, videos, or actual classroom observations of the kinds of challenging situations teachers encounter, teacher candidates could identify and practice coping strategies, emotional competence, reframing skills, and other resilient behaviors and ways of thinking” (2008, p. 71). Further, creating a supportive community is one of the protective factors to cultivate teachers’ resilience (Schussler et al., 2018). According to the findings of case studies conducted by Schessler and colleagues, having a community safety net helps teachers to identify the boundaries between their capabilities and limits, and feel motivated to overcome challenges. Support from professional development programs is especially critical to build teachers’ skills in which they feel less confident and increase their self-efficacy.

Experiential Learning

Learning is defined as “the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (Kolb, 1984, p. 38), and learning through experiences “involves a direct encounter with the phenomenon being studied rather than merely thinking about the encounter or only considering the possibility of doing something with it” (Keeton & Tate, 1978, p. 2). Experiential learning emphasizes the significance of active engagement and reflection as students learn by doing and reflecting on their experiences, and the cycle of learning includes knowledge internalization, application of knowledge, and analysis and synthesis of knowledge and activity (Kolb, 1984). Traditionally, preservice teachers learn theories, pedagogies, and practical strategies by taking courses with instructors. While learning content, the application of learned knowledge in teaching practice is one of the key elements that allows for experimentation between knowledge and practice. As one identifies and analyzes the gap between these two aspects, it is likely the potential factors that may cause gaps can be identified. In the field of ECE, the practicum is one of the most common forms that situates preservice teachers in authentic teaching environments in which they can actively collaborate with cooperating teachers and children and their families while incorporating pedagogical approaches into children’s daily learning environments. Even though practicum is essential in the teacher preparation programs, the practicum is insufficient to transform preservice teachers’ experiences if they are unable to reflect on their practicum experiences.

Video Analysis of Teaching

Reflection is the core of “intentional learning, problem-solving, and validity testing through rational discourse” (Mezirow, 1991, p. 99), and it requires practitioners to “critically assess the content, process, or premise of [their] efforts to interpret and give meaning to an experience” (p. 104). Attempts to critically evaluate and enact new practices are strengthened by systematic reflection. In particular, video analysis of teaching has frequently been utilized in teacher education programs to fine-tune instructional strategies for novice teachers (Hong & Riper, 2016; Moran et al., 2017; Nagro & deBettencourt, 2019). According to Nagro and Cornelius (2013), video analysis is defined as “a teacher teaching a lesson that is videotaped and then the teacher watches the video for the purpose of analyzing and reflecting on their own teaching performances” (p. 320). Previous research suggests that video analysis of teaching enhances teachers’ abilities to identify essential aspects of classroom interactions, challenge their existing knowledge and skills, and make changes to favorably influence their students’ learning (Hong & Riper, 2016; Kleinknecht & Schneider, 2013). According to Nagro et al. (2017), teachers who participate in reflection are more willing to acknowledge innovative ways to meet the needs of their students.

Guidance is required to facilitate preservice teachers’ evaluation of their methods during cycles of reflective practice. For example, guiding questions orient their focus on the analysis of teaching choices and why they do what they do, evaluation of the success or failure of those choices based on students’ learning outcomes, and implementation of revised plans for future lessons (Nagro et al., 2020). The ultimate goal of reflective practice is to extend beyond superficial summarization and revise instruction that can better meet the needs of students, therefore promoting prolonged growth in the profession. Overall, reflecting on teaching experiences is a critical process for preservice teachers to analyze their teaching practice that includes using language to make sense of their prior observations, planning next steps, and returning to the classroom for further growth.

Method

Participants

Three female preservice teachers at a university in the Northwestern U.S. consented for analysis of the work done in their courses. Pseudonyms (Charlotte, Delilah, and Harper) were assigned for confidentiality. They attended two courses: (1) Environments for Early Learning (EEL) in fall 2020 and (2) Creativity and Play (C&P) in winter 2021. The enrollments for each course were 14 and 17 students, respectively. Only three students who consented and completed all coursework participated in this study, and they have been in the ECE program since 2019 and have had different teaching experiences obtained through course practicum and part-time and/or volunteer work at different schools.

Due to the COVID-19, our school partners were unable to provide practicum opportunities, and the preservice teachers were encouraged to seek out families who needed learning experiences for their children at home in their local communities. All of them found one family to work with. However, this collaboration was based on strict precautions that demanded the preservice teachers to refrain from face-to-face interactions if they had any symptoms of cold, flu, or COVID-19.

Course Contexts

The ECE program offers more than 27 major courses and practicum and internship experiences for preservice teachers seeking a profession in ECE (birth through third grade) and specialization in working with young children and their families. In particular, EEL and C&P are the prerequisite courses that require preservice teachers to complete prior to preschool internship.

Environments for Early Learning in Fall 2020

The purpose of EEL was to (1) integrate theory, principles, and early childhood practices, (2) identify elements that are important to the design of the learning environment for young children, (3) transform space into engaging learning environments, and (4) use the inquiry-based learning approach integrated into curricula. This course was offered remotely due to the pandemic. Preservice teachers met me (author of the article) once a week via Zoom, and weekly class topics included measuring the quality of indoor and outdoor learning environments, inquiry-based learning, place-based learning, documenting child learning experiences, children’s hundred languages (Edwards et al., 1998) using natural and recycled materials, and the role of family and community in learning environments. This course consisted of lectures, readings and video analyses, and group discussions.

Preservice teachers were required to design and implement three lesson plans to foster children’s scientific inquiry using natural and recyclable materials as a component of one of the course assignments. Before lesson implementation, they interviewed families over Zoom to understand their needs, family routines, and expectations. Then, they worked with the children once a week until three lessons were implemented. Both Charlotte and Harper worked with the children over Zoom once a week, and each lesson was no longer than 30 min. On the other hand, Delilah implemented lessons at a child’s home. Families who worked with Harper and Delilah did not consent to be video recorded; thus, no video records are available for them. Although the family who worked with Charlotte consented to do that, only one video record was stored due to technical difficulties. Further, preservice teachers were given flexibility with the time to conduct their lessons due to families’ changes of meeting schedules or their emergency so that their feeling of stress can be lessened.

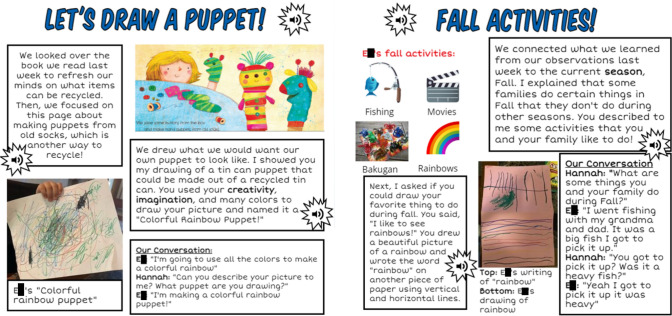

Preservice teachers were required to write a reflection report following each lesson delivery. In particular, they analyzed children’s learning outcomes, teaching strategies, and challenges and limitations of their teaching and to plan for future changes. Guidance questions were provided to help preservice teachers reflect (see Appendix). Furthermore, they created an eBook using the Book Creator app for the children and families, and this eBook was used as a summative assessment for child learning while assisting children and families in visualizing and celebrating learning experiences (see Fig. 1). In particular, eBook was perceived as pedagogical documentation that allowed preservice teachers to create and design narrations, texts, images, audios, and videos to highlight children’s learning moments and products (e.g., drawings, stories, and art artifacts).

Fig. 1.

Examples from Harper’s eBook

Creativity and Play in Winter 2021

The goal of C&P was to assist preservice teachers in developing the skills and techniques for working with children in the arts. It focused on cognitive and literacy development in the context of play by employing visual art, music, theatre, and dance/movement. This course was delivered virtually, with preservice teachers connecting with me twice a week. Weekly class topics included the nature of creativity, interconnection between play and creativity, inquiry project, storytelling using dramatization, dance, open-ended materials, clay, watercolor, and drawing, and documenting children’s learning experiences. This course incorporated lectures, readings and video analyses, activities, and group discussions.

Preservice teachers were required to implement four lesson plans to encourage children’s story creation and storytelling using a variety of art mediums as a component of one of the course assignments. Charlotte, Delilah, and Harper worked with the children over Zoom, and the average lesson lengths were between 24 and 39 min. All families consented to be video recorded by the preservice teachers. Further, preservice teachers were given flexibility with the time to conduct their lessons due to families’ changes of meeting schedules or their emergency so that their feeling of stress can be lessened.

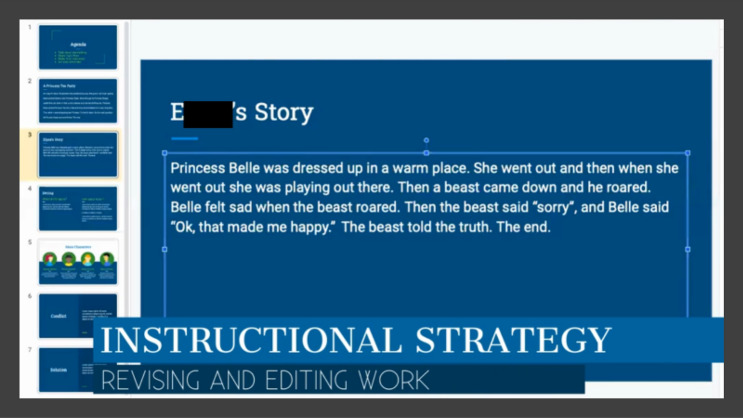

Preservice teachers were required to write a reflection report following each lesson implementation. In particular, they watched a video record of teaching, and then analyzed children’s learning outcomes, teaching strategies, and challenges and limitations of their teaching and to plan for future changes. Guiding questions were given to facilitate preservice teachers’ reflection (see Appendix). Moreover, they had to create a movie using the WeVideo app to present the sequence of implemented lessons in a cohesive manner and responses of the children to the lessons by embedding photographs, video clips, and child excerpts (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Example from Charlotte’s Movie. While the child was telling a story, the child could see Charlotte was taking the dictation on the PowerPoint over Zoom

The Role of Instructor

I, the course instructor, delivered the content, mentored, and guided preservice teachers. To minimize the stress for the children and preservice teachers, should I be present, I requested that they video record their teaching and share with me later for feedback. For example, when Harper reflected on her change of a dramatization lesson due to children’s shyness, I commented, “It reflects your flexibility to adapt your lesson plan based on the child’s needs and interests. Understandably, it was your first-time doing Zoom teaching, and the child might be shy to do it in front of the camera. Instead of forcing her, you immediately suggested that she could draw out her story, which she enjoyed a lot.” This comment represents not only the acknowledgment of the challenges Harper confronted but also my support toward her instructional decision.

Preservice teachers were encouraged to address their challenges in class as a small group so that they could share similar or unique challenges and brainstorm possible solutions to overcome them. The function of Breakout Rooms in Zoom was utilized for this purpose, and it also helped maintain the relationship with each other in this supportive community. As the literature indicated, this kind of relationship “boosts morale because they know what you are going through and can help keep your spirits up” (Howard & Johnson, 2004, p. 413). Besides shared challenges, some preservice teachers had personal questions and concerns that needed my support. To accomplish this, email communications and individual zoom meetings were scheduled as soon as possible so that they felt supported as they moved forward.

Data Source and Analysis

The distribution of the data across the two courses is mentioned in Table 1. Data from EEL included: (1) family interview reflection papers, (2) lesson reflection papers, (3) video records of teaching, and (4) eBooks. Data from C&P included: (1) lesson reflection papers, (2) video records of teaching, and (3) teaching movies.

Table 1.

The distribution of data across courses

| Course | Participants | Teaching mode | Family interview | Lesson reflections | Videos of teaching | Organized documentation (eBook/Movie) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environments for early learning | Charlotte | Online | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Delilah | In-Person | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Harper | Online | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Creativity and Play in ECE | Charlotte | Online | – | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Delilah | Online | – | 4 | 4 | 1 | |

| Harper | Online | – | 4 | 4 | 1 |

“–” means no assignment was arranged

Family interview reflection papers and teaching reflection papers were imported to the qualitative and mixed-method research analysis software, Dedoose, for coding. To identify the themes that consistently emerged, the constant comparative analysis was utilized (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Coding text was recursively executed, and codes sharing similar “metaphors” were grouped into categories. In particular, themes emerged that included online teaching challenges and applied strategies for online teaching. Moreover, video records, eBooks, and teaching movies were used for examining the trustworthiness of the analysis and the consistency between preservice teachers’ articulation of their experiences and their actual actions and language used in situ. For example, when a strategy and child learning outcomes were noted in students’ reflection papers, the associated video of teaching was reviewed to triangulate the data (eBook, reflection paper, and teaching movie) in an effort to establish trustworthiness. Cyclical analysis was preceded until the illustrations of associated reflection were identified.

Findings & Discussion

The goal of this study was to investigate the online teaching experiences of preservice teachers during the pandemic. One of the findings revealed that preservice teachers had to confront the challenges of not seeing critical aspects of a range of children’s learning processes while maintaining active engagement with the children.

Challenges of Online Teaching

Findings indicated that online teaching provided an opportunity for preservice teachers to work with children remotely during the pandemic while gaining teaching experiences. While working with children remotely, preservice teachers also experienced challenges regarding technology, the decision regarding the right time to step in, and child engagement.

Due to unstable internet, there was a lag over Zoom, causing the preservice teachers to occasionally talk over the children. In addition, not seeing children’s actions or progress created difficulty for preservice teachers’ ability to identify the appropriate time to step in. As Harper wrote,

I noticed it was challenging to know when to ask questions or comment while A was working on her sculpture. Like the watercolor lesson, I wanted to give her time to explore the playdough and make her sculpture. Since I could not see her process in making the sculpture, I thought I should periodically ask what she was doing to elicit language and support her thinking. However, I did not want to overwhelm her with questions or interrupt her sculpting. (C&P, Playdough Lesson)

She further expressed the concern of maintaining the child’s attention when she later reflected,

It was challenging to keep the lesson on the right track. Since this was over Zoom, it was also challenging to keep his attention focused away from distractions that were happening in his house. I also noticed while he was drawing, he would want to draw something unrelated to our activity and would want to move onto another picture quickly. (EEL, Recycle Lesson)

For Charlotte, child engagement was a persistent strand of concern as she expected the child to stay focused on the camera:

My child […] did not engage as much as I had hoped, however. Throughout the lesson, I noticed that her eyes were not on the camera, and I had to repeat questions more than once to get a response. (EEL, Read Aloud Lesson)

Online teaching creates personal experiences for preservice teachers to “initiate their process of inquiry and understanding” (Kolb, 1984, p. 11) even though it is uniquely challenging. As the participants of this study had no prior online teaching experiences, it created a new situation that required them to advance their abilities to recognize challenges and seek potential solutions. One of their biggest challenges was their inability to observe children’s full array of activity during the unfolding of a lesson. These gaps made it hard for them to decide what to do and the appropriate time to scaffold children’s learning. The children in the study were often given a laptop for Zoom class by their parents, and the camera of the laptop could only capture faces or the upper bodies of the children. Possible solutions in the future might include (1) parents recording their children using a smartphone, or (2) a phone holder set near to a child so that the smartphone could record a child’s activity without parent’s presence. However, these solutions would cause a financial burden for some families and require more involvement from parents who are also busy. Although the children and families in this study did not mention limited access to technology or the internet, from a broader perspective, this issue is still a reality and has been exacerbated by the pandemic and requirement of many teachers to teach online (Carrillo & Flores, 2020).

Applied Strategies for Online Teaching

Although preservice teachers confronted challenges, it did offer a unique learning opportunity for them to observe children in home environments and interactions between family members. The preservice teachers integrated family expectations into their planning of learning experiences for the children as “the family expects Zooms to be weekly and for them to not last past thirty minutes” (Charlotte, Family Interview Reflection). Another family also expressed that “they expect the child to at least try to do his remote preschool activities; however, they do not force it upon him” (Harper, Family Interview Reflection). Further, preservice teachers were able to overcome the hurdles by adopting a variety of strategies (modeling, using a child-centered approach, and patience).

Modeling

Across seven lessons, the preservice teachers utilized a variety of methods to encourage children’s active engagement, promote spoken language development and support inquiry learning. Modeling was used frequently and efficiently, in particular for online teaching. Harper described:

One strategy I used to support A’s thinking was modeling how I used the watercolors to create a scene in a story [see Figure 3]. This allowed A to see an example of how we can use watercolors to create or tell a story. It also showed that she could paint a scene of a story or paint a whole new story using watercolors. I also demonstrated the different techniques [splatter painting, crayon resist, wet paint, and tissue] we can use while water coloring and had her do the techniques with me. This showed different ways we can use watercolors on the page to create our pictures. It also allowed her to practice the techniques before painting her picture to tell a story. (C&P, Watercolor Lesson)

Fig. 3.

Examples of Harper’s Painting Using Watercolor Techniques. This painting was shared using PowerPoint

While modeling and integrating visual prompts using PowerPoint with demonstrations facilitated the understanding of the children through listening and observing, these strategies also motivated children’s interests to actively participate (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Examples of Harper’s Demonstration. Picture on the left is a material display, and pictures on the right are demonstrations of storytelling using materials. These pictures were presented to the child using PowerPoint

Child-Centered Approach

After the first lesson implementation, two of the preservice teachers’ emphasis in teaching shifted from keeping the lesson on track toward advocating child-centered learning. The participants had limited prior experiences of online teaching. When they started to work with children remotely, their concerns about completing a lesson on time were typical. After implementing the first lesson, Charlotte explained:

When I reviewed my lesson, I noticed that I spent a lot of time talking and maybe did not give J enough of an opportunity to speak. I was trying to keep the lesson on track, but in doing so, I might have missed some opportunities to uncover J’s thinking. (EEL, Recycle Lesson)

As the participants gradually felt comfortable with this model, their beliefs of the importance of a child-centered approach have emerged. As Charlotte reflected,

Something I noticed in my teaching was that I did not give [the child] much of an opportunity to create her own story or use her imagination. I think I got tunnel vision for what I wanted to see her do. I would like to make my lessons more child-directed and find ways to engage her in whom she is the one creating and deciding what she would like to do. (C&P, Dramatization Lesson)

Similarly, Harper decided to adapt her lesson plan and followed the child’s interest when the child was reluctant to role-play with her:

I also tried to model movement when we were going to dramatize the book. However, when I noticed she was reluctant and uncomfortable acting out the movements, we resulted in drawing the characters instead. I think she was still able to understand the characters and how they have different emotions based on events happening which could eventually lead to dramatization. (C&P, Dramatization Lesson)

Patience

In addition to the child-centered approach, the participants became more aware of the value of patience while working with young children. For example, Delilah reflected on her rushed response to a child’s question:

[….] When he was stuck on the word, Stroller that he didn’t remember what it was called, I asked him to describe the object. I should have waited for him to describe it instead of saying it was a baby stroller when he said the word baby. (EEL, Neighbor Walk)

For Charlotte, she had been practicing waiting for the child before rephrasing questions:

When I asked a question, I tried to wait 5 seconds before reiterating or rephrasing the question. I felt like I exercised more patience this week. Even when J was not as engaged as I had hoped, I still tried to slow down and understand why she was not engaged. (EEL, Read Aloud Lesson)

Similarly, Harper made sure to give the child enough time to think and respond:

After asking a question, I made sure to wait before I started talking again so that E had time to think and form his response and didn’t feel rushed. This seemed to work, as he normally responded a couple of seconds after my question when I didn’t say anything else. (EEL, Recycle Lesson)

It is evident that online teaching creates a context for preservice teachers to notice challenges and develop resilience to use different strategies to overcome them. Although different challenges emerged, the preservice teachers endeavored to adopt different strategies to fulfill the needs and interests of children, and this process cannot be segregated from reflection. As Tait elucidated, “working with scenarios, videos, or actual classroom observations of the kinds of challenging situations teachers encounter, teacher candidates could identify and practice coping strategies, emotional competence, reframing skills, and other resilient behaviors and ways of thinking” (2008, p. 71). In the study, video analysis enabled the preservice teachers to retrospectively analyze their teaching moments, evaluate their own and children’s language, gestures, and reactions, notice the impact of the teaching strategies, and adapt lesson plans for the next round of teaching.

As Nagro et al. (2020) reported, the ultimate goal of reflective practice is to revise instruction that can better serve students’ needs and promote prolonged growth in the profession. In particular, recursive reflection is needed to assist preservice teachers in internalizing reflection practices and making reflection a habit of their teaching. The promotion of recursive reflection across program courses needs to be incorporated. In this way, preservice teacher reflective practice becomes routinized and inextricably linked to students’ classroom practice regardless of course content or practical foci. To do this, teacher education programs should push for the incorporation of reflective practices across an array of teacher education course designs.

Conclusion

The global pandemic has influenced many teacher preparation programs to switch to online instruction. In order to continue training prospective teachers to meet the prerequisites for teacher licensing, preservice teachers in this study were required to work with children remotely and document and reflect on their online teaching experiences. Overall, findings from this study suggest that the preservice teachers confronted a variety of challenges while conducting online teaching; however, this unique experience seemed to sharpen their understandings of the complexity of children’s learning in home environments and provided them rich and authentic experiences to overcome the challenge using different strategies to adapt or modify teaching, virtually, through their development of resilience.

Even while online education attempts to mimic the social, cognitive, and teaching aspects of face-to-face classroom environments, it cannot match the complexity of classroom environments (e.g., classroom management, classroom arrangements, and classroom interactions, and classroom spaces). Integrating technology into ECE teaching has been improving; however, it is still debatable if classroom practicum can be substituted with online practical. Nevertheless, the need for future teachers to gain the knowledge and skills for both traditional and online teaching modalities should be acknowledged. Preservice teachers need to adapt instructional approaches based on the online modality because it is likely their students might face pandemic-similar situations or a plethora of academic and non-academic challenges in the future (Hill, 2021). Thus, equipping preservice teachers with knowledge and skills of both traditional, face-to-face practice and online teaching modalities seems essential to include in future teacher education programs.

This study was based on three preservice teachers’ course work over two quarters. More studies on the impact of virtual modality in teacher education programs are needed. Further, future studies with a diverse sample from a range of institutions, that include diverse cultural contexts, is crucial. Methodologically, future research should include ways to generate and analyze data (interviews, surveys, recurrent analyses of video recordings) that includes a wide range of contexts including home and center-based, a range of courses that include beginning and advanced coursework, and the role of learning communities in supporting practicum students’ teaching and resilience.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge Dr. Mary Jane Moran of the University of Tennessee for her invaluable comments and edits of the manuscript. Mary Jane Moran, Ph.D. Department of Child and Family Studies. The University of Tennessee. Email: mmoran2@utk.edu.

Appendix

Instructions: Each reflection paper requires you to copy and paste the associated link to the zoom meeting video. Answer the following questions to guide you to think critically about your teaching after watching the video clip:

What learning outcomes of the children did you notice? What evidence would support your evaluation? Evidence can be photographs, excerpts, artifacts, representations, etc.

How do the learning outcomes associate with the learning objectives you planned for this experience?

What strengths did you notice when you were working with children?

What strategies did you use that were efficient to scaffold children’s thinking and reasoning?

What challenges did you confront in teaching? What could you do differently next time when you work with children?

What limitation did you notice in terms of teaching? How would you like to work on that and improve?

Funding

There is no funding for this study.

Data Availability

Not Applicable.

Code Availability

Qualitative and mixed-method research analysis software, Dedoose is used for coding.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Participants have consented to use their course works for research analysis with the approval of the university Institutional Review Board.

Consent to Participate

Participants have consented to participate and to use their course works for research analysis with the approval of the university Institutional Review Board.

Consent for Publication

Participants understand the research analysis work will be published in journals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Beltman S, Mansfield CF, Price A. Thriving not just surviving: A review of research on teacher resilience. Educational Research Review. 2011;6:185–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04412.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berliner D. In pursuit of the expert pedagogue. Educational Researcher. 1986;15(7):5–13. doi: 10.2307/1175505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bobek BL. Teacher resiliency: A key to career longevity. The Clearing House. 2002;75(4):314–323. doi: 10.1080/00098650209604932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KG. Using computers to deliver training: Which employees learn and why? Personnel Psychology. 2001;54:271–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00093.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo C, Flores MA. COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. European Journal of Teacher Education. 2020;43(4):466–487. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1821184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. T. H. (2010). Knowledge and knowers in online learning: Investigating the effects of online flexible learning on student sojourners. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia]. Retrieved from https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4099&context=theses

- Day C, Gu Q. Resilient teachers, resilient schools: Building and sustaining quality in testing times. Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Day C, Hong J. Influences on the capacities for emotional resilience of teachers in schools serving disadvantaged urban communities: Challenges of living on the edge. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2016;59:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C, Gandini L, Forman G. The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education. Ablex; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Flores MA, Gago M. Teacher education in times of COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal: National, institutional and pedagogical responses. Journal of Education for Teaching. 2020;46(4):507–516. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1799709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gagné ED. The cognitive psychology of school learning. Little Brown; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison R. Theoretical challenges for distance education in the 21st century: A shift from structural to transactional issues. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. 2000;1(1):1–8. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v1i1.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Pub; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Greeno JG, Collins AM, Resnick LB. Cognition and learning. In: Berliner D, Calfee R, editors. Handbook of educational psychology. Simon & Schuster Macmillan; 1996. pp. 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Day C. Challenges to teacher resilience: Conditions count. British Educational Research Journal. 2013;39(1):22–44. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2011.623152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JB. Pre-service teacher experiences during COVID-19: Exploring the uncertainties between clinical practice and distance learning. Journal of Practical Studies in Education. 2021;2(2):1–13. doi: 10.46809/jpse.v2i2.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong CE, Riper IV. Enhancing teacher learning from guided video analysis of literacy instruction: An interdisciplinary and collaborative approach. Journal of Inquiry & Action in Education. 2016;7(2):94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hong JY. Why do some beginning teachers leave the school, and others stay? Understanding teacher resilience through psychological lenses. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice. 2012;18(4):417–440. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2012.696044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howard S, Johnson B. Resilient teachers: Resisting stress and burnout. Social Psychology of Education. 2004;7(4):399–420. doi: 10.1007/s11218-004-0975-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huber SG, Helm C. COVID-19 and schooling: Evaluation, assessment and accountability in times of crises—Reacting quickly to explore key issues for policy, practice and research with the school barometer. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability. 2020;32:237–270. doi: 10.1007/s11092-020-09322-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd, J., Rember, B. A., Pellegrini, T., Ludlow, B., & Meisner, J. (2020, July 9). “This is not teaching”: The effects of COVID-19 on teachers. Social Publishers Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/this-is-not-teaching-the-effects-of-covid-19-on-teachers/

- Kaldi S. Student teachers’ perceptions of self-competence in and emotions/stress about teaching in initial teacher education. Educational Studies. 2009;35(3):349–360. doi: 10.1080/03055690802648259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keeton M, Tate P. Learning by experience—What, why, how. Jossey-Bass; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly N, Sim C, Ireland M. Slipping through the cracks: Teachers who miss out on early career support. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education. 2018;46:1–25. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2018.1441366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana, C. (2016). Exploring the role of multimedia in enhancing social presence in an asynchronous online course. [Doctoral Dissertation, The State University of New Jersey, Rutgers, U.S.]. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/docview/1844392065?pq-origsite=primo

- Klassen RM, Durksen TL, Al Hashmi W, Kim LE, Longden K, Metsäpelto R, Poikkeus A, Gyori JG. National context and teacher characteristics: Exploring the critical non-cognitive attributes of novice teachers in four countries. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2018;72:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinknecht M, Schneider J. What do teachers think and how do they feel when they analyze videos of themselves teaching and of other teacher teaching? Teaching and Teacher Education. 2013;33:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2013.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb DA. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, C. F. (2020). Cultivating teacher resilience: International approaches, applications and impact. Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. Retrieved from https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/id/3cc0ec4b-fe63-48c7-b634-01e69fd95af5/2021_Book_CultivatingTeacherResilience.pdf

- Mansfield CF, Beltman S, Broadley T, Weatherby-Fell N. Building resilience in teacher education: An evidenced informed framework. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2016;54:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Powell JL. A resilience framework for research, policy and practice. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood. Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow J. Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Moran MJ, Bove C, Brookshire R, Braga P, Mantovani S. Learning from each other: The design and implementation of a cross-cultural research and professional development model in Italian and U.S. toddler classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2017;63:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagro SA, Cornelius KE. Evaluating the evidence base of video analysis: A special education teacher development tool. Teacher Education and Special Education. 2013;35:312–329. doi: 10.1177/0888406413501090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagro SA, deBettencourt LU. Reflection activities within clinical experiences: An important component of field-based teacher education. In: Hodges TE, Baum AC, editors. The handbook of research on field-based teacher education. IGI Global; 2019. pp. 565–586. [Google Scholar]

- Nagro SA, deBettencourt LU, Rosenberg MS, Carran DT, Weiss MP. The effects of guided video analysis on teacher candidates’ reflective ability and instructional skills. Teacher Education and Special Education. 2017;40(1):7–25. doi: 10.1177/0888406416680469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagro SA, Hirsch SE, Kennedy MJ. A self-led approach to improving classroom management practices using video analysis. Teaching Exceptional Children. 2020;53(1):24–32. doi: 10.1177/0040059920914329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty D, Dromey M, Lougheed J, Hannigan A, Last J, McGrath D. Barriers and solutions to online learning in medical education—An integrative review. (Report) BMC Medical Education. 2018;18(1):130–141. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammons P, Day C, Kington A, Gu Q, Stobart G, Smees R. Exploring variations in teachers’ work, lives and their effects on pupils: Key findings and implications from a longitudinal mixed-method study. British Educational Research Journal. 2007;33(5):681–701. doi: 10.1080/01411920701582264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schussler DL, Deweese A, Rasheed D, Demauro A, Brown J, Greenberg M, Jennings PA. Stress and release: Case studies of teacher resilience following a mindfulness-based intervention. American Journal of Education. 2018;125(1):1–18. doi: 10.1086/699808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stronge J. Qualities of effective teachers. ASCD; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tait M. Resilience as a contributor to novice teacher success, commitment, and retention. Teacher Education Quarterly. 2008;35(4):57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, C. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Ungar M. Social ecologies and their contribution to resilience. In: Ungar M, editor. The social ecology of resilience: A handbook of theory and practice. Springer; 2012. pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Yost DS. Reflection and self-efficacy: Enhancing the retention of qualified teachers from a teacher education perspective. Teacher Education Quarterly. 2006;33(4):59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wang Y, Yang L, Wang CH. Suspending classes without stopping learning: China’s education emergency management policy in the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2020;13(58):1–6. doi: 10.3390/jrfm13030055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Qualitative and mixed-method research analysis software, Dedoose is used for coding.