Abstract

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved cell survival mechanism that degrades damaged proteins and organelles to generate cellular energy during times of stress. Recycling of these cellular components occurs in a series of sequential steps with multiple regulatory points (1). Mechanistic dysfunction can lead to a variety of human diseases and cancers due to the complexity of autophagy and its ability to regulate vital cellular functions. The role that autophagy plays in both the development and treatment of cancer is highly complex, especially given the fact that most cancer therapies modulate autophagy (2). This review aims to discuss the balance of autophagy in the development, progression, and treatment of head and neck cancer, as well as highlighting the need for a deeper understanding into what is still unknown about autophagy.

Keywords: autophagy, cancer, radiation, chemotherapy

Introduction

Types of autophagy

Autophagy can be classified into three types (Figure 1): microautophagy, macroautophagy, and chaperon-mediated autophagy (CMA) (1). It is important to note that both macro- and microautophagy can be further classified as either selective or nonselective. Nonselective autophagy is primarily utilized for cell survival purposes and involves the random engulfment of damaged cytoplasmic components destined for non-specific degradation in a lysosome. Selective autophagy targets specific organelles and can be classified according to its target; for example, mitochondrial autophagy is termed mitophagy, peroxisomal autophagy termed pexophagy, ribosomal autophagy termed ribophagy, etc (3).

Figure 1. Types of autophagy.

There are three major types of autophagy. a) Macroautophagy involves the fusion of the autophagosome and lysosome to degrade damaged cytosolic cargos. Autophagy can occur either via non-selective (bulk) degradation or through selective elimination of cytosolic components including different dysfunctional organelles such as mitochondria and ribosomes. b) Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) occurs independent of the autophagosome and lysosomal invagination. Chaperone proteins, such as Hsc70, recognize cytosolic cargo destined by degradation by their consensus sequence known as the KFERQ-like motif. c) Microautophagy is the process where lysosomes directly engulf cytosolic components via invagination of the lysosomal membrane.

While macroautophagy involves the formation of a phagophore and subsequent fusion of the autophagosome with a lysosome for cargo digestion, microautophagy involves the direct engulfment of cytoplasmic substrates within lysosomes via tubular invaginations. In this sense it is non-selective; however, there are three forms of selective microautophagy that each target specific organelles for lysosomal degradation, these being micropexophagy (peroxisomes), piecemeal microautophagy of the nucleus (PMN), and micromitophagy (mitochondria) (4). It has been found that microautophagy is involved in many neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s (5) and Huntington’s disease (6), but its specific link to cancer development is unknown (4).

Unlike both micro- and macroautophagy, chaperon-mediated autophagy (CMA) is a highly specific form of autophagy that recognizes the amino acid motif KFERQ through binding to the cytosolic chaperone protein (HSC70). The lysosomal protein LAMP2A then delivers this specific substrate to the lysosome for internalization and subsequent degradation (2,7).

The term “autophagy” commonly refers to macroautophagy, as it is the most studied of the three. We will use the term autophagy to refer to macroautophagy throughout this review. Double membraned vesicles known as autophagosomes first sequester the damaged cytoplasmic organelles and proteins. The autophagosome then fuses with hydrolase-containing lysosomes to form an autolysosome; this structure is then able to enzymatically degrade the original cargo into its constituent macromolecules and free amino acids for metabolic reuse (8)(9).

Signaling pathways of autophagy

The signaling pathway of autophagy is highly complex and involves over 30 autophagy related genes (Atgs, Figures 2 and 3); these genes are involved in various stages such as initiation, nucleation of the autophagosome, elongation of the autophagosome, lysosome fusion, and finally degradation (10). The presence of Atg homologs in multiple higher eukaryotes suggests that the autophagy pathway is highly evolutionarily conserved (11,12).

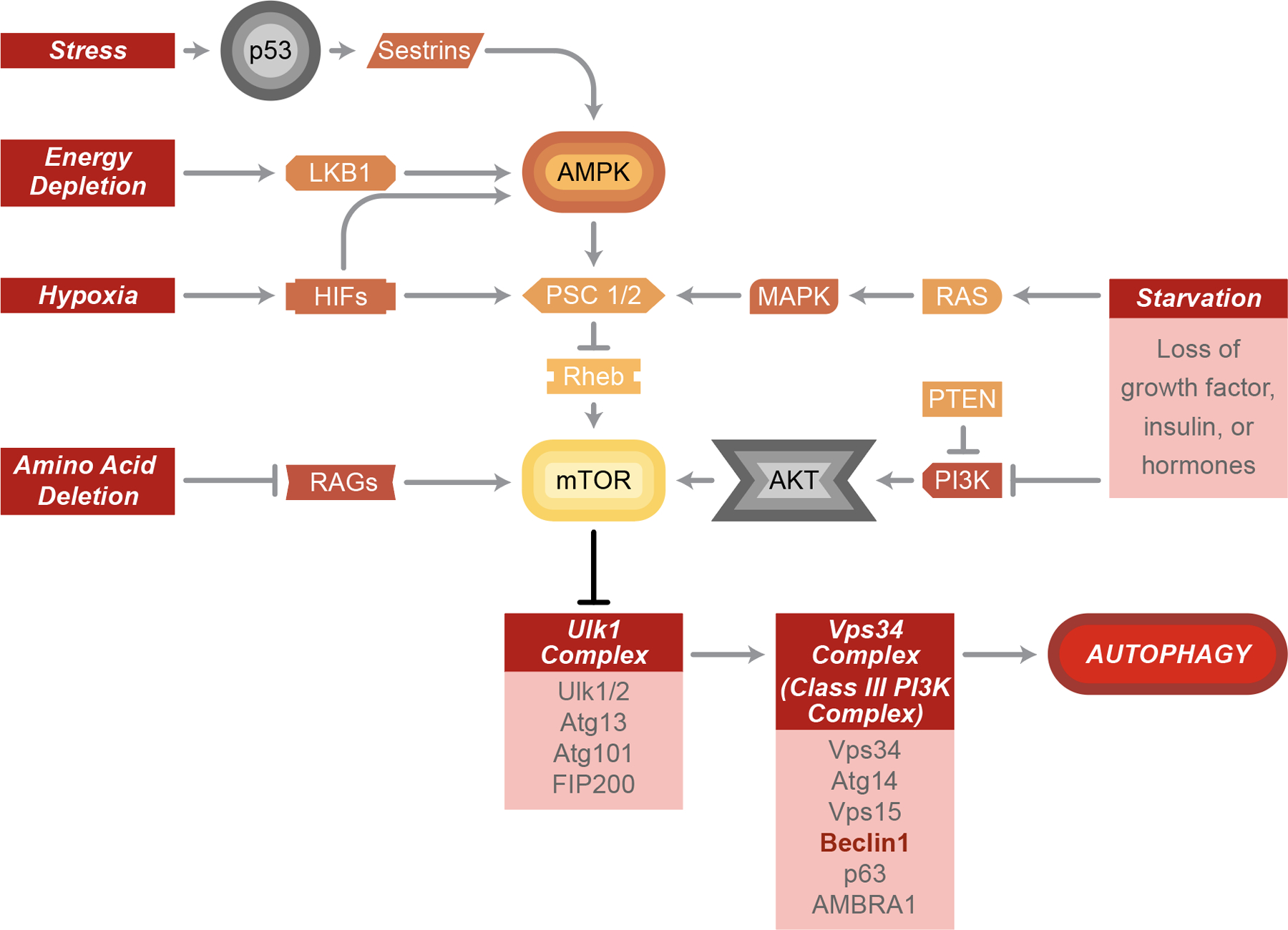

Figure 2. Cellular stress-induced autophagy.

Autophagy induction can be mediated by the AMPK-mTOR pathway in response to various cellular stresses, such as starvation, hypoxia, amino acid depletion, energy depletion and stress. Once mTOR has been inhibited, the downstream Ulk1 and Vps34 complex will be activated and then further initiate autophagy maturation.

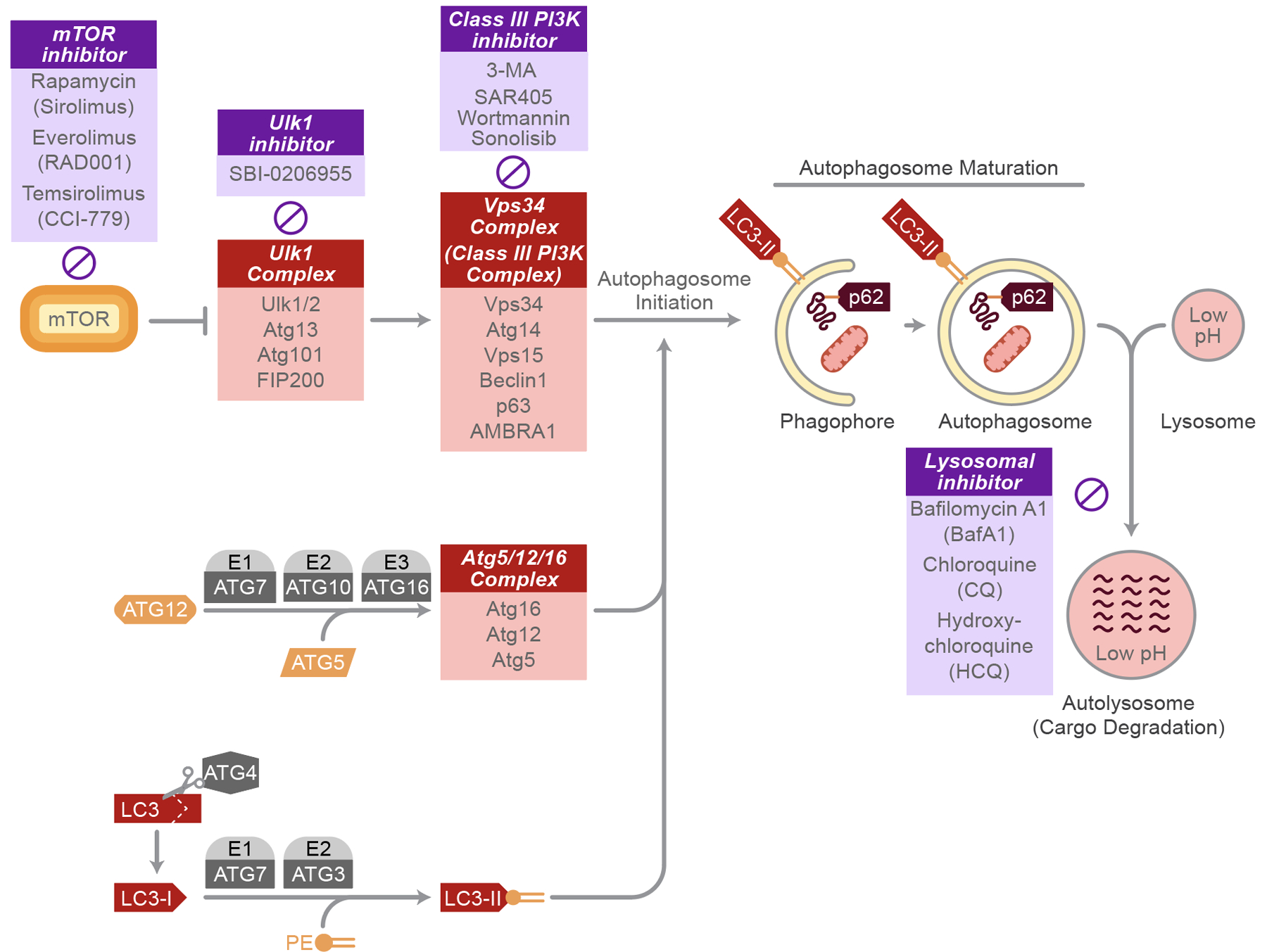

Figure 3. Signaling pathway of autophagy and autophagy inhibitors.

Activated Vps34 complex cooperates with the Atg5/12/16 complex and LC3II to maturate autophagosomes. Damaged proteins or organelles labeled with p62 are engulfed in autophagosomes and ultimately fuse with lysosomes for degradation or recycling. Several inhibitors have been developed (purple boxes) to suppress autophagy at different steps.

Initiation of autophagy begins with the formation of the autophagosome at the phagophore assembly site (PAS), where Atg proteins are recruited and the phagophore expands (11). Formation of the PAS is regulated by both the mTOR/Atg13/ULK1 complex and the Beclin/Vps34 complex (10). The ULK1 complex goes on to activate the class III PI3K complex, itself consisting of the vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 34 (Vps34), Atg14, vp63, and BECN1-regulated autophagy protein 1 (AMBRA1), all scaffolded by the tumor suppressor Beclin-1 to allow for their interaction with each other (13). Vps34 is required for the formation of new autophagosomes; inhibition of Vps34 via 3-methyladenine inhibits autophagosome formation (14). Likewise, inhibition of ULK1 via the pre-clinical compound SBI-0206955 (15) prevents autophagosome formation. The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is able to directly phosphorylate ULK1 as a method of autophagy inhibition, making it a popular target for anti-cancer therapies (16). Inhibition of Beclin-1 via binding of the B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) antiapoptotic proteins is an additional route to autophagy inhibition (17). Finally, inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor (IP3R) complexes with Beclin-1 to inhibit autophagy; this effect can be reversed using the IP3R antagonist, xestospongin B, that disrupts this complex (18).

Autophagosome membrane expansion requires two ubiquitin-like reactions, the Atg5-Atg12 complex and MAP1-LC3/LC3/Atg8 complex (10). Atg12 is conjugated to a lysine residue of Atg5 in a series of activation reactions by Atg7 and Atg10, forming the Atg5-Atg12 complex (19). Atg5-Atg12 is further linked to Atg16, creating the Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 complex required for autophagosome membrane elongation and eventually dissociates from the membrane (20). The second conjugation involves microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3 or Atg8) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), whereby LC3 is cleaved to form LC3-I via Atg4 (21). LC3-I undergoes conjugation with PE to form LC3-II in a reaction with Atg7 and Atg3. Unlike LC3-I or other complexes, LC3-II continues to be associated with the autophagosome membrane until its final degradation in the autolysosome (22). Crosstalk exists between these two complexes. For example, the Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 complex may help in the conjugation of LC3-I to PE (23). Dysfunction in any of the conjugation systems will result in unsuccessful autophagosome membrane formation (24).

Autophagosomes first fuse with endosomes to begin maturation. To engulf cellular substrates, p62 (Sequestosome 1 or SQSTM1) binds to ubiquitin to allow for the delivery of cargo to the autophagosomes (25). There are several proteins required to mediate the fusion process as well as provide GTPase activity, such as the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) machinery, soluble NSF attachment protein receptors (SNAREs), Ras-related protein 7 (Rab7), and the class C Vps proteins; loss of function of each of these can lead to dysregulated maturation (26–29). Autophagosomes ultimately fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes in the final step of the autophagy mechanism, in which damaged proteins and organelles are degraded. Autophagic flux can be calculated as a measure of autophagy by examining LC3-II and p62 levels, as both are degraded in the autolysosome (22).

Autophagy and apoptosis

Cytoplasmic organelles and whole cells are constantly regulated by both autophagy, the process of self-eating, and apoptosis, the process of self-killing (30). The relationship between these mechanisms is highly complex and may be triggered by common upstream signals, resulting in their concurrent activation. These common regulators include the tumor suppressor protein TP53, BH3-only proteins, death-associated protein kinase (DAPK), and JUN N-terminal kinase (JNK) (31). Activated DAPK can regulate the dissociation of Beclin 1 from Bcl-2, triggering autophagy in this manner (32). JNK-1 can also trigger autophagy in a similar fashion wherein JNK-1 promotes phosphorylation of Bcl-2, leading to Bcl-2 dissociation from Beclin 1 and subsequent activation of autophagy (33).

TP53 is a well-studied tumor suppressor protein, having effects on metabolism, antioxidant defense, genomic stability, proliferation, senescence, cell death, and most notably is able to induce autophagy following DNA damage (34). While TP53 has not been found to directly interact with any of the core Atg proteins, it can activate pro-autophagic genes such as AMPK, TSC2, PTEN, DRAM, or Sesn1/2 to induce autophagy (35). The BH3-only proteins BAD, BID, NOXA, and PUMA interact with Bcl-2 to release Beclin-1, an autophagy initiator (31). Conversely, the BH3-only protein BIM inhibits autophagy through interaction with Beclin-1, as well as mediating apoptosis (36). Beclin-1, after being unbound from BCL-2, complexes with VPS34 to help facilitate autophagy protein localization to autophagosome membranes (17).

Further investigations into the relationship between autophagy and apoptosis has been conducted in colon cancer cells. It has been shown that a shift from autophagy to apoptosis can occur through a caspase-8 dependent manner wherein caspase-8 co-localizes with the proteins LC3-II and LAMP2, autophagic markers on autophagosomes. Caspase-8, normally involved in signaling apoptosis, can be degraded by the autophagic machinery, hindering its activity (37). Conversely, activation of apoptosis can also suppress autophagy through Bax-mediated cleavage of Beclin-1. Cleavage of Beclin-1 interrupts its interaction with VPS34, a required step in the initiation of autophagy (38).

Autophagy in the development and progression of cancer

The association of autophagy with cancers

The precise role of autophagy in cancer remains highly complex. Autophagy has been shown to play a role in both evasion of cell death and maintenance of homeostasis through cellular recycling programs, and in the promotion of cell death through large-scale degradation of cellular components (39). While autophagy can be induced to limit cancer proliferation and progression, tumor cells can also take advantage of this machinery to promote metastasis and survival in times of nutrient deprivation. For example, tumor suppressor proteins including TP53, PTEN, DAPK, TSC1, and TSC2 are commonly mutated in cancer and can provide the cell with signals to activate autophagy (39). The precise role of autophagy as a pro- or anti-survival process may be both stage and environment specific (40).

During the early stages of tumorigenesis, autophagy can act as a tumor suppressor. For example, Bif-1 can interact with Beclin-1 through UV radiation-resistance-associated gene (UVRAG) to act as a tumor suppressor and positive regulator of autophagy (41). The gene encoding Beclin-1 is decreased or deleted in 70% of breast cancer, 52% of prostate cancer, and 75% of ovarian cancer (42–44); this loss of Beclin-1 promotes cell proliferation and mitigates the cytoprotective role autophagy typically plays (45). This finding suggests that Beclin-1 functions as a tumor suppressor, as it usually is involved in the formation of the phagophore in the autophagy mechanism (46). Conversely, overexpression of Beclin-1 has been found to promote apoptosis and suppress tumorigenesis in MKN-45 gastric cancer cells (47). Additionally, frameshift mutations in Atg2B, Atg5, Atg9B, and Atg12 are common in gastric and colorectal carcinomas, suggesting that impaired activation of autophagy might contribute to cancer development (48). The observation that mutations in autophagy core proteins results in carcinogenesis suggests that autophagy is an important mechanism involved in tumor inhibition. Not surprisingly, the most commonly mutated gene in cancer, TP53, plays a complex role in autophagy where it can act as either as an autophagy promotor or autophagy inhibitor. Wild type TP53 can activate autophagy genes in response to conditions of cellular stress, such as oncogenesis, whereas mutated cytoplasmic TP53 has been shown to repress autophagy (49).

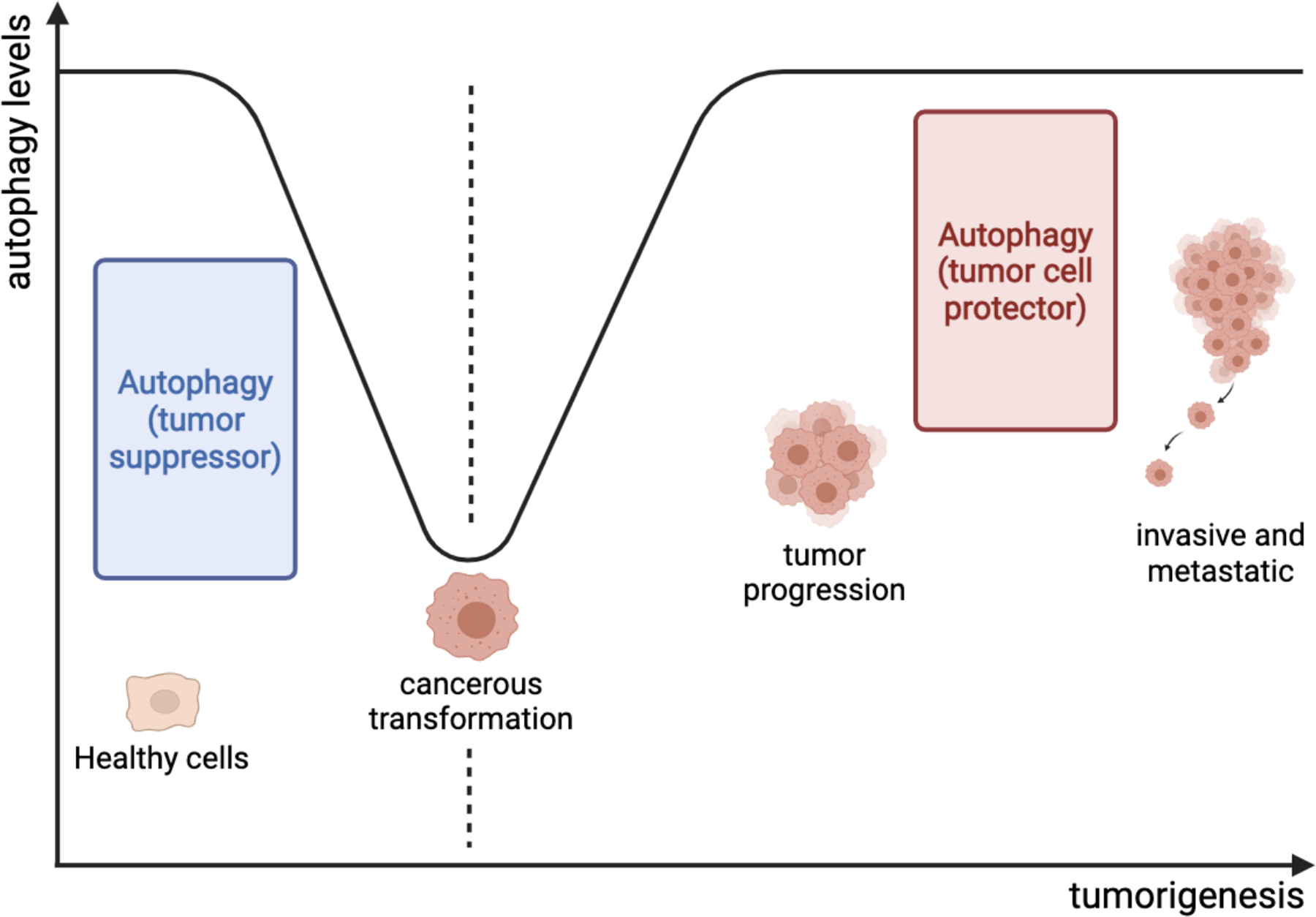

Although autophagy can help to suppress initial tumor development (Figure 4), it can also help tumor cells overcome the extreme stressors they face, such as hypoxia and nutrient deprivation (46). To fulfill the increased metabolic and energetic needs, tumors cells take advantage of autophagic machinery to recycle intracellular components, supplying the necessary substrates to promote cell survival (50). A study found that Ras-mutated cancer cells maintained higher levels of basal autophagy and possessed an “autophagy addiction” required to sustain cell survival and tumor growth during times of limited nutrients (51). There also is evidence that low Atg5 expression in melanoma promotes tumorigenesis, as Atg5 normally inhibits proliferation and induces cell senescence (52). Together, these findings imply that autophagy is used to increase stress tolerance and provide tumor cells with the appropriate nutrients to support their survival.

Figure 4. The role of autophagy in tumorigenesis.

Autophagy acts to protect healthy cells from malignant transformation. Once the malignancy has been established, the loss of autophagy has been proposed as a biomarker for the initiation of early-stage cancers. As tumors progress, autophagy becomes a cellular protector to help cancer grow and survive in a resource-limited microenvironment.

Autophagy in the treatment of cancer

The challenges of modulating autophagy in cancer therapy

Autophagy’s dual role of cytotoxicity and cytoprotection poses an immense challenge to anti-cancer treatment approaches. Drug-induced autophagy has been employed as an attempt to kill cancer cells, particularly in those that have adopted anti-apoptotic strategies. However, an opposite approach has been taken wherein autophagy is inhibited as an attempt to overcome the treatment resistance conferred by autophagy (53). It should be noted that there are currently no FDA approved compounds that were developed specifically to inhibit autophagy. Rather, autophagy modulation was discovered as an off-target effect. Our group and others are actively investigating whether chemotherapy and radiotherapy can be enhanced with the addition of autophagy modulators to improve tumor control and prevent the development of therapeutic resistance, as autophagy has numerous effects on cancer treatments. There remains a significant need for an improved understanding of how autophagy can be modulated to improve the care of cancer patients.

Effect of chemotherapy on autophagy

Current cancer therapies such as radiation and chemotherapy induce cytotoxic stress capable of triggering pro-survival autophagy in cancer cells, demonstrating the complicated role of autophagy in anticancer therapy (54,55). Many cancers, including nearly all (i.e. 90%) HNCs, are associated with EGFR overexpression, with more aggressive phenotypes corresponding to increased EGFR levels (56,57). EGFR is an upstream regulator of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, which is itself activated in 47% of HNCs with EGFR activation, making it an attractive target for cancer therapies (58). This pathway controls cell proliferation, survival, and modulates gene expression, as well as governing autophagy regulation (59). Many commonly used chemotherapy agents can induce autophagy, emphasizing a need to better understand this mechanism (60).

Gefitinib, also known as Iressa or ZD1839, is an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor that acts by binding to the ATP site on EGFR, blocking activation of downstream AKT/ERK/STAT3 signaling (61,62). Clinical efficacy is unfortunately minimal, with a 10–15% HNC patient response to treatment (62–64). The anti-cancer effects of gefitinib, including upregulation of apoptosis, were found to be enhanced when used in combination with MK-2206, an allosteric inhibitor of Akt, a kinase family with inhibitory effects on apoptosis (65). However, gefitinib is also able to activate autophagy and promote cell survival through an EGFR-independent pathway, which suggests that the use of autophagy inhibitors in combination with gefitinib could work together to improve treatment efficacy (66).

Erlotinib, also known as Tarceva or OSI-774, is another EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets the ATP binding site within EGFR and prevents downstream signal activation (67). Treatment with erlotinib leads to a 29% response rate in patients with HNC (68). The NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) enzyme is increased by erlotinib treatment, leading to erlotinib-induced cytotoxicity and production of H2O2 to drive cell death. This points to a potential therapeutic approach in which erlotinib could be used in combination with conventional therapies that additionally increase oxidative stress to amplify its effects (69). At low concentrations, erlotinib triggers autophagy to provide cells with necessary energy and nutrients as an attempt at survival. Conversely, high doses of erlotinib have been found to cause autophagic cell death; this effect is further increased with the addition of autophagy inhibitors to treatment (70).

Saracatinib, also known as AZD0530, is a small molecule inhibitor of Src family kinases (Src, Yes, Fyn, Lyn, Lck, Hck, Fgr, Blk, Yrk) which are involved in cellular processes including proliferation, adhesion, invasion, migration, and tumorigenesis (71). Higher levels of Src have been correlated with more advanced cancers (72,73). The ability of saracatinib to block Src through the Vimentin/Snail signaling pathway suppresses cancer cell metastasis in HNC, both in vitro and in vivo (74). Unfortunately, a phase II clinical trial of single agent saracatinib failed to demonstrate efficacy (75). The disappointing clinical results suggest that underlying mechanisms of resistance such as autophagy may play a key role in determining which cancers respond to these targeted therapies; for example, in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Src inhibition induces cytoprotective autophagy through PI3K signaling. Simultaneous inhibition of autophagy with saracatinib increased cytotoxicity (76). Similarly, Src was seen to induce high levels of autophagy through the PI3K signaling pathway in prostate cancer cells. Combining saracatinib and chloroquine, an autophagy inhibitor, resulted in higher levels of apoptosis as well as a 64% inhibition of tumor growth in mouse models (77). This combination of saracatinib plus autophagy inhibition may reveal better tumor control in clinical settings.

Cetuximab, also known as Erbitux or IMC-225, is a IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to the EGFR ligand binding domain resulting in both inactivation and receptor internalization (78). Blocking EGFR ligand binding has many anti-cancer effects including inhibition of tumor growth, impairment of DNA damage repair, and increased cell death (79). Due to the extremely high rate of EGFR overexpression in HNC, cetuximab has been a popular treatment option, particularly for those patients unable to tolerate cytotoxic chemotherapy. However, responses to cetuximab monotherapy hover around 20% (80). Cetuximab promotes EGFR translocation to the nucleus, which has been linked to resistance to cetuximab (81). Fortunately, the Src protein family inhibitor dasatinib has showed promising results in inhibiting cetuximab-mediated EGFR nuclear translocation (82). Another promising multi-drug treatment for HNC is the combination of cetuximab and cisplatin, in which response to treatment increased from 20% to 35% (80,83). Cetuximab induces autophagy both by inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and activation of the Vps34/Beclin-1 pathway as indicated by an increase in LC3-II accumulation, characteristic of increased autophagic flux. Interestingly, the addition of rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor and autophagy inducer, to cetuximab treatment increased apoptosis in cetuximab-resistant cells (84).

Panitumumab, also known as Vectibix or ABX-EGF, is a monoclonal IgG2 antibody which inhibits EGFR (85). As compared to IgG1 antibodies like cetuximab, IgG2 antibodies are not anticipated to induce antibody-dependent cellular toxicity (ADCC) (86,87). Panitumumab improved progression-free survival with low cytotoxicity in a phase III HNC clinical trial, although it did not improve overall patient survival in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy (88). In combination with radiotherapy, panitumumab augmented in vitro efficacy by enhancing radiation-induced DNA damage as well as blocking EGFR nuclear translocation, both of which can increase apoptosis (87). Little is known regarding the connection between panitumumab and autophagy; nonetheless it has been found that Beclin-1, a marker of autophagy, is increased in cells treated with panitumumab (89).

Effect of radiation therapy on autophagy

Radiation therapy is a common treatment for many cancer patients, but unfortunately it has been shown to increase autophagy significantly in cancer cells (54). Autophagy appears to enhance cancer cell killing following radiation (90). Consistent with this, rapamycin increases the efficacy of radiotherapy by increasing radiation-induced cell death (91,92). Combination treatment with radiation and rapamycin increases autophagy and leads to increased cell death in an oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cell line, showing that induction of autophagy may help increase the anti-cancer effects of radiotherapy (93). Pretreating radiation-resistant cells with 3-methyladenine (3-MA) or chloroquine can increase efficacy of irradiation treatment compared to irradiation alone (94). While this helps establish autophagy’s role as a tumor suppressor, it has also been reported that autophagy can exhibit cytoprotective effects in radiation-treated cells, acting as a tumor promotor (95). The precise relationship between autophagy and radiotherapy continues to be elucidated and may be partially dependent on where in the autophagy pathway inhibition occurs and the dose of radiation utilized (96).

Induction of autophagy in head and neck cancer

Given the dual role that autophagy plays in cells as both a tumor suppressor and tumor promotor (Figure 4), several drugs have been developed to regulate either the induction or inhibition of autophagy (Figure 3). The main pathway targeted by autophagy inducers is the mTOR/Akt signaling pathway as it normally is a negative regulator of autophagy (31).

Rapamycin, also known as Rapamune or sirolimus, targets and inhibits mTOR through the formation of a FKBP12-rapamycin-mTOR complex, and through this induces autophagy (97). Rapamycin can also induce apoptosis in HNC and additionally has a synergistic effect in combination with other cytotoxic agents such as radiation, cisplatin, carboplatin, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, topotecan, and mitoxantrone (98). While rapamycin can induce autophagy, inhibition of autophagy decreased the cytotoxicity of rapamycin, demonstrating that autophagy is an important aspect of rapamycin treatment efficacy (99).

Everolimus, also known as Afinitor or RAD001, is a derivative of rapamycin that also inhibits mTOR and activates autophagy. Induction of autophagy by everolimus enhances sensitivity to other therapies such as doxorubicin and radiation, as well as promoting autophagy-mediated programmed cell death. Everolimus-mediated autophagy leads to Met inactivation and Src activation, suggesting that Src inhibitors may synergize with everolimus (100).

Temsirolimus, also known as Torisel or CCI-779, is yet another derivative of rapamycin that partially inhibits mTOR by complexing with the FK506 binding protein (101). Temsirolimus improves the efficacy of traditional therapies when combined with irradiation, anti-EGFR, and anti-angiogenic therapies in HNC (102). As expected, temsirolimus can induce autophagy due to its effects on the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Temsirolimus was also found to promote G1 cell cycle arrest through the downregulation of p21, and although not cytotoxic, did modestly increase cell death when used at high concentrations (103).

Inhibition of autophagy in head and neck cancer

Autophagy activation is known to be involved in the progression of many types of cancers; regulating autophagy induction would be beneficial for improving treatment. Two potential inhibitors of autophagy, chloroquine, and its derivate hydroxychloroquine, have been investigated for their ability to block autophagy in cancer. Other autophagy inhibitors are currently in development but have not yet received FDA approval (Figure 3).

The anti-inflammatory drug chloroquine blocks autophagy by inhibiting lysosomal fusion with autophagosomes; hypothesized to occur due to chloroquine-induced Golgi and endosomal disorganization (104). Increased cell death was achieved using combination treatment of chloroquine with cisplatin, erlotinib, and saracatinib in vitro (70,77,105). Chloroquine greatly improved glioblastoma treatment response both when treated alone (106) and in combination with conventional therapies (107). Another study reported that chloroquine has additional autophagy-independent methods of reducing cancer cell invasion and metastasis (108).

Hydroxychloroquine, also known as Plaquenil, functions similarly to chloroquine and synergizes with CYT997, a microtubule-disrupting agent, to trigger oxidative stress-associated apoptosis in HNC (109). Hydroxychloroquine is a successful autophagy inhibitor on its own, but combination with current therapies demonstrate the largest effect. A clinical trial on canines with lymphoma showed a 93.3% response rate when treated with hydroxychloroquine and doxorubicin (110). Combination treatment of hydroxychloroquine with gemcitabine, a chemotherapy drug, yielded a 61% response rate in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma with additional improvements in overall survival (111).

Role of autophagy-related genes (ARGs) in the prediction of the prognosis for head and neck cancer patients

Recent studies have suggested that autophagy-related genes (ARGs) may be useful as either predictive or prognostic cancer biomarkers. This includes work in lung adenocarcinoma (112), glioblastoma (113), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (114), breast cancer (115), ovarian cancer (116), and head and neck cancer (117). For example, in head and neck cancer, 232 ARGs in 515 patients were analyzed within the TCGA database; ARGs were highly associated with the regulation of apoptosis, the ErbB pathway, HIF-1 pathway, platinum drug resistance, PD-L1 expression, and the PD-1 checkpoint pathway (117).

Conclusion

Autophagy not only controls cellular homeostasis but also plays a critical role in cancer development leading from healthy cells to metastatic or drug-resistant tumors (Figure 4). This multistep regulation highlights the opportunities for pharmacologic intervention in the multi-step process of autophagy, as well as its potential for serving as a predictive or prognostic cancer biomarker. Initially, autophagy protects healthy cells from malignant transformation. However, defects in the autophagic process might facilitate the acquisition of malignant features by healthy cells. Once malignancy is established, autophagy assumes the role of cell protector against cellular stresses from microenvironments including alkylating agents and irradiation. This may help establish treatment resistance in cancer cells. In this phase, the restoration of autophagic responses may be essential to support cancer cell survival and proliferation in the presence of adverse microenvironmental conditions. The exact strength of these autophagic responses required to fight against cellular stresses remains unknown, as evidence in support of this model is lacking. Lastly, autophagy inhibitors have exhibited an ability to be useful additives to current alkylating agents or irradiation in several studies, but convincing evidence from clinical trials has not yet been presented. These emphasize the unmet experimental and medical needs to further understand the use of autophagy in HNC therapies and ultimately improve treatment outcomes for patients suffering from this disease.

Acknowledgements:

University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA014520

UW Head and Neck SPORE Grant P50 DE026787

American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant (RSG-16-091-01-TBG) and Mission Boost Grant (BG-18-205-01-COUN)

All Figures created with BioRender.com

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest with the included work to disclose.

Data availability:

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- 1.Parzych KR, Klionsky DJ. An Overview of Autophagy: Morphology, Mechanism, and Regulation. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2014. Jan 20;20(3):460–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorburn A, Thamm DH, Gustafson DL. Autophagy and Cancer Therapy. Mol Pharmacol. 2014. Jun;85(6):830–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin M, Liu X, Klionsky DJ. SnapShot: Selective autophagy. Cell. 2013. Jan 17;152(1–2):368–368.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li W, Li J, Bao J. Microautophagy: lesser-known self-eating. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012. Apr;69(7):1125–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nixon RA. Autophagy, amyloidogenesis and Alzheimer disease. Journal of Cell Science. 2007. Dec 1;120(23):4081–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martίn-Aparicio E, Yamamoto A, Hernández F, Hen R, Avila J, Lucas JJ. Proteasomal-Dependent Aggregate Reversal and Absence of Cell Death in a Conditional Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. J Neurosci. 2001. Nov 15;21(22):8772–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaushik S, Massey AC, Cuervo AM. Lysosome membrane lipid microdomains: novel regulators of chaperone-mediated autophagy. EMBO J. 2006. Sep 6;25(17):3921–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khandia R, Dadar M, Munjal A, Dhama K, Karthik K, Tiwari R, et al. A Comprehensive Review of Autophagy and Its Various Roles in Infectious, Non-Infectious, and Lifestyle Diseases: Current Knowledge and Prospects for Disease Prevention, Novel Drug Design, and Therapy. Cells. 2019. Jul 3;8(7):674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klionsky DJ, Codogno P. The Mechanism and Physiological Function of Macroautophagy. J Innate Immun. 2013;5(5):427–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW, et al. Regulation of Mammalian Autophagy in Physiology and Pathophysiology. Physiological Reviews. 2010. Oct;90(4):1383–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways of Autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009. Dec;43(1):67–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meijer WH, van der Klei IJ, Veenhuis M, Kiel JAKW. ATG Genes Involved in Non-Selective Autophagy are Conserved from Yeast to Man, but the Selective Cvt and Pexophagy Pathways also Require Organism-Specific Genes. Autophagy. 2007. Mar 27;3(2):106–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy JMM, Towers CG, Thorburn A. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017. Sep;17(9):528–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seglen PO, Gordon PB. 3-Methyladenine: Specific inhibitor of autophagic/lysosomal protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1982. Mar 1;79(6):1889–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egan DF, Chun MGH, Vamos M, Zou H, Rong J, Miller CJ, et al. Small Molecule Inhibition of the Autophagy Kinase ULK1 and Identification of ULK1 Substrates. Molecular Cell. 2015. Jul;59(2):285–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong P-M, Puente C, Ganley IG, Jiang X. The ULK1 complex: Sensing nutrient signals for autophagy activation. Autophagy. 2013. Feb 28;9(2):124–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, et al. Bcl-2 Antiapoptotic Proteins Inhibit Beclin 1-Dependent Autophagy. Cell. 2005. Sep;122(6):927–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vicencio JM, Ortiz C, Criollo A, Jones AWE, Kepp O, Galluzzi L, et al. The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor regulates autophagy through its interaction with Beclin 1. Cell Death Differ. 2009. Jul;16(7):1006–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizushima N, Sugita H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. A New Protein Conjugation System in Human. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998. Dec;273(51):33889–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizushima N, Kuma A, Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto A, Matsubae M, Takao T, et al. Mouse Apg16L, a novel WD-repeat protein, targets to the autophagic isolation membrane with the Apg12-Apg5 conjugate. Journal of Cell Science. 2003. May 1;116(9):1679–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemelaar J, Lelyveld VS, Kessler BM, Ploegh HL. A Single Protease, Apg4B, Is Specific for the Autophagy-related Ubiquitin-like Proteins GATE-16, MAP1-LC3, GABARAP, and Apg8L. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003. Dec;278(51):51841–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H, Agostinis P, Agrawal DK, Aliev G, Askew DS, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy. 2008. Feb 16;4(2):151–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanada T, Noda NN, Satomi Y, Ichimura Y, Fujioka Y, Takao T, et al. The Atg12-Atg5 Conjugate Has a Novel E3-like Activity for Protein Lipidation in Autophagy. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007. Dec;282(52):37298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujita N, Hayashi-Nishino M, Fukumoto H, Omori H, Yamamoto A, Noda T, et al. An Atg4B Mutant Hampers the Lipidation of LC3 Paralogues and Causes Defects in Autophagosome Closure. Subramani S, editor. MBoC. 2008. Nov;19(11):4651–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birgisdottir ÅB, Lamark T, Johansen T. The LIR motif – crucial for selective autophagy. Journal of Cell Science. 2013. Aug 1;126(15):3237–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rusten TE, Vaccari T, Lindmo K, Rodahl LMW, Nezis IP, Sem-Jacobsen C, et al. ESCRTs and Fab1 Regulate Distinct Steps of Autophagy. Current Biology. 2007. Oct;17(20):1817–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutierrez MG, Munafó DB, Berón W, Colombo MI. Rab7 is required for the normal progression of the autophagic pathway in mammalian cells. Journal of Cell Science. 2004. Jun 1;117(13):2687–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber T, Zemelman BV, McNew JA, Westermann B, Gmachl M, Parlati F, et al. SNAREpins: Minimal Machinery for Membrane Fusion. Cell. 1998. Mar;92(6):759–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Filimonenko M, Stuffers S, Raiborg C, Yamamoto A, Malerød L, Fisher EMC, et al. Functional multivesicular bodies are required for autophagic clearance of protein aggregates associated with neurodegenerative disease. Journal of Cell Biology. 2007. Nov 5;179(3):485–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mariño G, Niso-Santano M, Baehrecke EH, Kroemer G. Self-consumption: the interplay of autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014. Feb;15(2):81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhat P, Kriel J, Shubha Priya B, Basappa, Shivananju NS, Loos B. Modulating autophagy in cancer therapy: Advancements and challenges for cancer cell death sensitization. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2018. Jan;147:170–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zalckvar E, Berissi H, Mizrachy L, Idelchuk Y, Koren I, Eisenstein M, et al. DAP-kinase-mediated phosphorylation on the BH3 domain of beclin 1 promotes dissociation of beclin 1 from Bcl-XL and induction of autophagy. EMBO Rep. 2009. Mar;10(3):285–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei Y, Pattingre S, Sinha S, Bassik M, Levine B. JNK1-Mediated Phosphorylation of Bcl-2 Regulates Starvation-Induced Autophagy. Molecular Cell. 2008. Jun;30(6):678–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Djavaheri-Mergny M, D’Amelio M, et al. Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53. Nat Cell Biol. 2008. Jun;10(6):676–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao W, Shen Z, Shang L, Wang X. Upregulation of human autophagy-initiation kinase ULK1 by tumor suppressor p53 contributes to DNA-damage-induced cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2011. Oct;18(10):1598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo S, Garcia-Arencibia M, Zhao R, Puri C, Toh PPC, Sadiq O, et al. Bim Inhibits Autophagy by Recruiting Beclin 1 to Microtubules. Molecular Cell. 2012. Aug;47(3):359–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hou W, Han J, Lu C, Goldstein LA, Rabinowich H. Autophagic degradation of active caspase-8: A crosstalk mechanism between autophagy and apoptosis. Autophagy. 2010. Oct;6(7):891–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo S, Rubinsztein DC. Apoptosis blocks Beclin 1-dependent autophagosome synthesis: an effect rescued by Bcl-xL. Cell Death Differ. 2010. Feb;17(2):268–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhutia SK, Mukhopadhyay S, Sinha N, Das DN, Panda PK, Patra SK, et al. Autophagy. In: Advances in Cancer Research [Internet]. Elsevier; 2013. [cited 2021 Sep 13]. p. 61–95. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780124071735000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kenific CM, Thorburn A, Debnath J. Autophagy and metastasis: another double-edged sword. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2010. Apr;22(2):241–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi Y, Coppola D, Matsushita N, Cualing HD, Sun M, Sato Y, et al. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007. Oct;9(10):1142–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Z, Chen B, Wu Y, Jin F, Xia Y, Liu X. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of the beclin 1gene in sporadic breast tumors. BMC Cancer. 2010. Dec;10(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao X, Zacharek A, Salkowski A, Grignon DJ, Sakr W, Porter AT, et al. Loss of heterozygosity of the BRCA1 and other loci on chromosome 17q in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1995. Mar 1;55(5):1002–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aita VM, Liang XH, Murty VVVS, Pincus DL, Yu W, Cayanis E, et al. Cloning and Genomic Organization of Beclin 1, a Candidate Tumor Suppressor Gene on Chromosome 17q21. Genomics. 1999. Jul;59(1):59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chavez-Dominguez R, Perez-Medina M, Lopez-Gonzalez JS, Galicia-Velasco M, Aguilar-Cazares D. The Double-Edge Sword of Autophagy in Cancer: From Tumor Suppression to Pro-tumor Activity. Front Oncol. 2020. Oct 7;10:578418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yun C, Lee S. The Roles of Autophagy in Cancer. IJMS. 2018. Nov 5;19(11):3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Xie J, Wang H, Huang H, Xie P. Beclin-1 suppresses gastric cancer progression by promoting apoptosis and reducing cell migration. Oncol Lett [Internet]. 2017. Sep 25 [cited 2021 Sep 13]; Available from: http://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/ol.2017.7046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang MR, Kim MS, Oh JE, Kim YR, Song SY, Kim SS, et al. Frameshift mutations of autophagy-related genes ATG2B, ATG5, ATG9B and ATG12 in gastric and colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability: ATG gene mutations. J Pathol. 2009. Apr;217(5):702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mrakovcic M, Fröhlich L. p53-Mediated Molecular Control of Autophagy in Tumor Cells. Biomolecules. 2018. Mar 21;8(2):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu EY, Ryan KM. Autophagy and cancer – issues we need to digest. Journal of Cell Science. 2012. Jan 1;jcs.093708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo JY, Chen H-Y, Mathew R, Fan J, Strohecker AM, Karsli-Uzunbas G, et al. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes & Development. 2011. Mar 1;25(5):460–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu H, He Z, von Rutte T, Yousefi S, Hunger RE, Simon H-U. Down-Regulation of Autophagy-Related Protein 5 (ATG5) Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Early-Stage Cutaneous Melanoma. Science Translational Medicine. 2013. Sep 11;5(202):202ra123–202ra123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bishop E, Bradshaw TD. Autophagy modulation: a prudent approach in cancer treatment? Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2018. Dec;82(6):913–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim B, Hong Y, Lee S, Liu P, Lim J, Lee Y, et al. Therapeutic Implications for Overcoming Radiation Resistance in Cancer Therapy. IJMS. 2015. Nov 10;16(11):26880–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sui X, Chen R, Wang Z, Huang Z, Kong N, Zhang M, et al. Autophagy and chemotherapy resistance: a promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2013. Oct;4(10):e838–e838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Santini J, Formento J-L, Francoual M, Milano G, Schneider M, Dassonville O, et al. Characterization, quantification, and potential clinical value of the epidermal growth factor receptor in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Head Neck. 1991. Mar;13(2):132–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalyankrishna S, Grandis JR. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Biology in Head and Neck Cancer. JCO. 2006. Jun 10;24(17):2666–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marquard FE, Jücker M. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling as a molecular target in head and neck cancer. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2020. Feb;172:113729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu JSL, Cui W. Proliferation, survival and metabolism: the role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling in pluripotency and cell fate determination. Development. 2016. Sep 1;143(17):3050–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rikiishi H. Autophagic action of new targeting agents in head and neck oncology. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2012. Sep;13(11):978–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wakeling AE, Guy SP, Woodburn JR, Ashton SE, Curry BJ, Barker AJ, et al. ZD1839 (Iressa): an orally active inhibitor of epidermal growth factor signaling with potential for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2002. Oct 15;62(20):5749–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pernas FG, Allen CT, Winters ME, Yan B, Friedman J, Dabir B, et al. Proteomic Signatures of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor and Survival Signal Pathways Correspond to Gefitinib Sensitivity in Head and Neck Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009. Apr 1;15(7):2361–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ranson M, Hammond LA, Ferry D, Kris M, Tullo A, Murray PI, et al. ZD1839, a Selective Oral Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor–Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor, Is Well Tolerated and Active in Patients With Solid, Malignant Tumors: Results of a Phase I Trial. JCO. 2002. May 1;20(9):2240–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baselga J, Rischin D, Ranson M, Calvert H, Raymond E, Kieback DG, et al. Phase I Safety, Pharmacokinetic, and Pharmacodynamic Trial of ZD1839, a Selective Oral Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor, in Patients With Five Selected Solid Tumor Types. JCO. 2002. Nov 1;20(21):4292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng Y, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Ren X, Huber-Keener KJ, Liu X, et al. MK-2206, a Novel Allosteric Inhibitor of Akt, Synergizes with Gefitinib against Malignant Glioma via Modulating Both Autophagy and Apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012. Jan;11(1):154–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Han W, Pan H, Chen Y, Sun J, Wang Y, Li J, et al. EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Activate Autophagy as a Cytoprotective Response in Human Lung Cancer Cells. Zhang L, editor. PLoS ONE. 2011. Jun 2;6(6):e18691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abdelgalil AA, Al-Kahtani HM, Al-Jenoobi FI. Erlotinib. In: Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology [Internet]. Elsevier; 2020. [cited 2021 Sep 15]. p. 93–117. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1871512519300196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vergez S, Delord J-P, Thomas F, Rochaix P, Caselles O, Filleron T, et al. Preclinical and Clinical Evidence that Deoxy-2-[18 F]fluoro-D-glucose Positron Emission Tomography with Computed Tomography Is a Reliable Tool for the Detection of Early Molecular Responses to Erlotinib in Head and Neck Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010. Sep 1;16(17):4434–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Orcutt KP, Parsons AD, Sibenaller ZA, Scarbrough PM, Zhu Y, Sobhakumari A, et al. Erlotinib-Mediated Inhibition of EGFR Signaling Induces Metabolic Oxidative Stress through NOX4. Cancer Res. 2011. Jun 1;71(11):3932–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eimer S, Belaud-Rotureau M-A, Airiau K, Jeanneteau M, Laharanne E, Véron N, et al. Autophagy inhibition cooperates with erlotinib to induce glioblastoma cell death. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2011. Jun 15;11(12):1017–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Summy JM, Gallick GE. Treatment for Advanced Tumors: Src Reclaims Center Stage: Fig. 1. Clin Cancer Res. 2006. Mar 1;12(5):1398–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Talamonti MS, Roh MS, Curley SA, Gallick GE. Increase in activity and level of pp60c-src in progressive stages of human colorectal cancer. J Clin Invest. 1993. Jan 1;91(1):53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Allgayer H, Boyd DD, Heiss MM, Abdalla EK, Curley SA, Gallick GE. Activation of Src kinase in primary colorectal carcinoma: An indicator of poor clinical prognosis. Cancer. 2002. Jan 15;94(2):344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lang L, Shay C, Xiong Y, Thakkar P, Chemmalakuzhy R, Wang X, et al. Combating head and neck cancer metastases by targeting Src using multifunctional nanoparticle-based saracatinib. J Hematol Oncol. 2018. Dec;11(1):85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fury MG, Baxi S, Shen R, Kelly KW, Lipson BL, Carlson D, et al. Phase II study of saracatinib (AZD0530) for patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Anticancer Res. 2011. Jan;31(1):249–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rothschild SI, Gautschi O, Batliner J, Gugger M, Fey MF, Tschan MP. MicroRNA-106a targets autophagy and enhances sensitivity of lung cancer cells to Src inhibitors. Lung Cancer. 2017. May;107:73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu Z, Chang P-C, Yang JC, Chu C-Y, Wang L-Y, Chen N-T, et al. Autophagy Blockade Sensitizes Prostate Cancer Cells towards Src Family Kinase Inhibitors. Genes & Cancer. 2010. Jan 1;1(1):40–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sunada H, Magun BE, Mendelsohn J, MacLeod CL. Monoclonal antibody against epidermal growth factor receptor is internalized without stimulating receptor phosphorylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1986. Jun 1;83(11):3825–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mehra R. The contribution of cetuximab in the treatment of recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck cancer. BTT. 2010. Jun;173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, Remenar E, Kawecki A, Rottey S, et al. Platinum-Based Chemotherapy plus Cetuximab in Head and Neck Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008. Sep 11;359(11):1116–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wheeler DL, Iida M, Kruser TJ, Nechrebecki MM, Dunn EF, Armstrong EA, et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor cooperates with Src Family Kinases in acquired resistance to cetuximab. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2009. Apr 15;8(8):696–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li C, Iida M, Dunn EF, Wheeler DL. Dasatinib blocks cetuximab- and radiation-induced nuclear translocation of the epidermal growth factor receptor in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2010. Nov;97(2):330–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de Mello RA, Gerós S, Alves MP, Moreira F, Avezedo I, Dinis J. Cetuximab Plus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Study in a Single Comprehensive European Cancer Institution. Ganti AK, editor. PLoS ONE. 2014. Feb 6;9(2):e86697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li X, Lu Y, Pan T, Fan Z. Roles of autophagy in cetuximab-mediated cancer therapy against EGFR. Autophagy. 2010. Nov 16;6(8):1066–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Foon KA, Yang X-D, Weiner LM, Belldegrun AS, Figlin RA, Crawford J, et al. Preclinical and clinical evaluations of ABX-EGF, a fully human anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2004. Mar;58(3):984–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kawaguchi Y, Kono K, Mimura K, Sugai H, Akaike H, Fujii H. Cetuximab induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against EGFR-expressing esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: Cetuximab for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2007. Feb 15;120(4):781–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kruser TJ, Armstrong EA, Ghia AJ, Huang S, Wheeler DL, Radinsky R, et al. Augmentation of Radiation Response by Panitumumab in Models of Upper Aerodigestive Tract Cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2008. Oct;72(2):534–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vermorken JB, Stöhlmacher-Williams J, Davidenko I, Licitra L, Winquist E, Villanueva C, et al. Cisplatin and fluorouracil with or without panitumumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SPECTRUM): an open-label phase 3 randomised trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2013. Jul;14(8):697–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Giannopoulou E, Antonacopoulou A, Matsouka P, Kalofonos HP. Autophagy: novel action of panitumumab in colon cancer. Anticancer Res. 2009. Dec;29(12):5077–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tam SY, Wu VWC, Law HKW. Influence of autophagy on the efficacy of radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 2017. Dec;12(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Paglin S, Lee N-Y, Nakar C, Fitzgerald M, Plotkin J, Deuel B, et al. Rapamycin-Sensitive Pathway Regulates Mitochondrial Membrane Potential, Autophagy, and Survival in Irradiated MCF-7 Cells. Cancer Res. 2005. Dec 1;65(23):11061–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim KW, Mutter RW, Cao C, Albert JM, Freeman M, Hallahan DE, et al. Autophagy for Cancer Therapy through Inhibition of Pro-apoptotic Proteins and Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006. Dec;281(48):36883–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wu S-Y, Liu Y-W, Wang Y-K, Lin T-H, Li Y-Z, Chen S-H, et al. Ionizing radiation induces autophagy in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. J BUON. 2014. Mar;19(1):137–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chaachouay H, Ohneseit P, Toulany M, Kehlbach R, Multhoff G, Rodemann HP. Autophagy contributes to resistance of tumor cells to ionizing radiation. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2011. Jun;99(3):287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grácio D, Magro F, T. Lima R, Máximo V. An overview on the role of autophagy in cancer therapy. Hematol Med Oncol [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2021 Sep 16];2(1). Available from: http://oatext.com/An-overview-on-the-role-of-autophagy-in-cancer-therapy.php [Google Scholar]

- 96.Apel A, Herr I, Schwarz H, Rodemann HP, Mayer A. Blocked Autophagy Sensitizes Resistant Carcinoma Cells to Radiation Therapy. Cancer Res. 2008. Mar 1;68(5):1485–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hausch F, Kozany C, Theodoropoulou M, Fabian A-K. FKBPs and the Akt/mTOR pathway. Cell Cycle. 2013. Aug;12(15):2366–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Aissat N, Le Tourneau C, Ghoul A, Serova M, Bieche I, Lokiec F, et al. Antiproliferative effects of rapamycin as a single agent and in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in head and neck cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008. Jul;62(2):305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Iwamaru A, Kondo Y, Iwado E, Aoki H, Fujiwara K, Yokoyama T, et al. Silencing mammalian target of rapamycin signaling by small interfering RNA enhances rapamycin-induced autophagy in malignant glioma cells. Oncogene. 2007. Mar;26(13):1840–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lin C-I, Whang EE, Donner DB, Du J, Lorch J, He F, et al. Autophagy Induction with RAD001 Enhances Chemosensitivity and Radiosensitivity through Met Inhibition in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2010. Sep;8(9):1217–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rini BI. Temsirolimus, an Inhibitor of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin. Clin Cancer Res. 2008. Mar 1;14(5):1286–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bozec A, Etienne-Grimaldi M-C, Fischel J-L, Sudaka A, Toussan N, Formento P, et al. The mTOR-targeting drug temsirolimus enhances the growth-inhibiting effects of the cetuximab–bevacizumab–irradiation combination on head and neck cancer xenografts. Oral Oncology. 2011. May;47(5):340–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yazbeck VY, Buglio D, Georgakis GV, Li Y, Iwado E, Romaguera JE, et al. Temsirolimus downregulates p21 without altering cyclin D1 expression and induces autophagy and synergizes with vorinostat in mantle cell lymphoma. Experimental Hematology. 2008. Apr;36(4):443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mauthe M, Orhon I, Rocchi C, Zhou X, Luhr M, Hijlkema K-J, et al. Chloroquine inhibits autophagic flux by decreasing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy. 2018. Aug 3;14(8):1435–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.New J, Arnold L, Ananth M, Alvi S, Thornton M, Werner L, et al. Secretory Autophagy in Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Promotes Head and Neck Cancer Progression and Offers a Novel Therapeutic Target. Cancer Res. 2017. Dec 1;77(23):6679–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Briceño E, Reyes S, Sotelo J. Therapy of glioblastoma multiforme improved by the antimutagenic chloroquine. FOC. 2003. Feb;14(2):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sotelo J, Briceño E, López-González MA. Adding Chloroquine to Conventional Treatment for Glioblastoma Multiforme: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006. Mar 7;144(5):337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Maes H, Kuchnio A, Peric A, Moens S, Nys K, De Bock K, et al. Tumor Vessel Normalization by Chloroquine Independent of Autophagy. Cancer Cell. 2014. Aug;26(2):190–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gao L, Zhao X, Lang L, Shay C, Andrew Yeudall W, Teng Y. Autophagy blockade sensitizes human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma towards CYT997 through enhancing excessively high reactive oxygen species-induced apoptosis. J Mol Med. 2018. Sep;96(9):929–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Barnard RA, Wittenburg LA, Amaravadi RK, Gustafson DL, Thorburn A, Thamm DH. Phase I clinical trial and pharmacodynamic evaluation of combination hydroxychloroquine and doxorubicin treatment in pet dogs treated for spontaneously occurring lymphoma. Autophagy. 2014. Aug 20;10(8):1415–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Boone BA, Bahary N, Zureikat AH, Moser AJ, Normolle DP, Wu W-C, et al. Safety and Biologic Response of Pre-operative Autophagy Inhibition in Combination with Gemcitabine in Patients with Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015. Dec;22(13):4402–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang X, Yao S, Xiao Z, Gong J, Liu Z, Han B, et al. Development and validation of a survival model for lung adenocarcinoma based on autophagy-associated genes. J Transl Med. 2020. Dec;18(1):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wang Y, Zhao W, Xiao Z, Guan G, Liu X, Zhuang M. A risk signature with four autophagy‐related genes for predicting survival of glioblastoma multiforme. J Cell Mol Med. 2020. Apr;24(7):3807–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yue P, Zhu C, Gao Y, Li Y, Wang Q, Zhang K, et al. Development of an autophagy-related signature in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2020. Jun;126:110080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lin Q-G, Liu W, Mo Y, Han J, Guo Z-X, Zheng W, et al. Development of prognostic index based on autophagy-related genes analysis in breast cancer. Aging. 2020. Jan 22;12(2):1366–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.An Y, Bi F, You Y, Liu X, Yang Q. Development of a Novel Autophagy-related Prognostic Signature for Serous Ovarian Cancer. J Cancer. 2018;9(21):4058–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jin Y, Qin X. Development of a Prognostic Signature Based on Autophagy-related Genes for Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Archives of Medical Research. 2020. Nov;51(8):860–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.