Abstract

Introduction

Ubrogepant is a calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist indicated for acute treatment of migraine that can be used to treat breakthrough attacks in individuals taking preventive treatment for migraine. We evaluated the impact of preventive medication use on the efficacy and safety of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine.

Methods

This was an analysis of pooled efficacy data from the ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II phase 3 trials, in which efficacy of ubrogepant was assessed at 2 h after taking study medication for pain freedom, absence of most bothersome symptom (MBS), and pain relief. In addition, a long-term safety (LTS) extension trial was completed where safety was assessed on the basis of incidence and severity of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs). Outcomes were compared between participants with or without prior (within 6 months) preventive medication use (anticonvulsants, beta blockers, antidepressants, or onabotulinumtoxinA). For efficacy analyses, data were pooled across ACHIEVE trials for the 50 mg and placebo groups; for safety analyses, data for all dose groups (50 mg and 100 mg) in the LTS trial were pooled.

Results

Preventive treatments were used by 417 of 2247 (18.6%) participants analyzed in the ACHIEVE trials and by 143 of 813 (17.5%) participants in the LTS trial. Responder rates for all outcomes were similar between participants with or without preventive treatment within each dose group (p > 0.05). No significant differences were noted across the different preventive medications. Rates and types of TEAEs were similar between participants with or without preventive treatment. No serious treatment-related adverse events were reported.

Conclusion

Efficacy and safety of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine were similar between participants with or without prior or current use of concomitant preventive medication.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02828020 (ACHIEVE I), NCT02867709 (ACHIEVE II), and NCT02873221 (long-term safety trial).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-021-01923-3.

Keywords: Acute treatment, Concomitant therapies, Migraine, Preventive treatment, Ubrogepant

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Migraine is a chronic neurologic disease characterized by recurrent attacks that involve headache, as well as neurologic and autonomic symptoms that can be disabling. |

| Acute treatments are often used to reduce migraine-related symptoms and disability associated with attacks; however, a subset of individuals may also require preventive treatment to reduce the frequency of attacks and these individuals represent a more severely affected subgroup due to greater attack frequency, severity, or both. |

| The objective of this analysis was to evaluate the impact of preventive medication use on the efficacy and safety of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Ubrogepant was associated with significant efficacy across all three outcome measures (pain freedom, absence of most bothersome symptom, and pain relief at 2 h after ubrogepant administration) in people with migraine regardless of preventive medication use, and responder rates were not significantly different between participants with or without preventive medication use. |

| The results of this study indicate that ubrogepant is safe to use with the preventive medications assessed in this analysis, and can be applied to clinical practice, especially when considering the potential for drug–drug interactions. |

Introduction

Migraine is a chronic, often life-long neurologic disease that is characterized by recurrent and disabling attacks [1–4]. Migraine involves neurologic symptoms beyond headache, including vision changes, difficulty speaking and reading, increased emotionality, sensory hypersensitivity, gastrointestinal disturbances, neck discomfort, tiredness, yawning, food cravings, as well as the typical symptoms of phonophobia, photophobia, and nausea with or without vomiting [1, 5, 6]. Acute treatments are often used to shorten the attack and reduce the pain, migraine-related symptoms, and disability associated with individual attacks [7]. However, a subset of individuals with frequent attacks or disability may also require preventive treatment to reduce the overall frequency of attacks [7–9]. Successful preventive treatment has been reported to positively impact an individual’s response to acute medication [10]. Conversely, failure to adequately respond to preventive treatment may be associated with a negative impact on acute treatment efficacy. Given the potential impact of preventive medication use on acute treatment efficacy, it is of clinical interest to evaluate the impact, if any, of prior or concomitant preventive medication use on the efficacy and safety of acute treatment options for migraine.

Ubrogepant is a highly selective, small-molecule, oral, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonist approved for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults [11–14]. Although many participants with migraine enrolled in clinical trials to evaluate acute treatment for migraine with ubrogepant were not taking preventive medications, those with disease severity sufficient to seek care from a headache specialty clinic were likely to be treated with a preventive medication. This group of participants with current or prior history of preventive medication use may represent a more severe population with significant unmet treatment needs [15–18], where safe and effective combinations of acute and preventive treatments are necessary. The objective of this analysis was to evaluate the impact of preventive medication use on the efficacy and safety of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine. For these analyses, efficacy was evaluated on the basis of pooled data from the ACHIEVE trials and safety was evaluated on the basis of data from the subsequent long-term safety (LTS) extension trial.

Methods

Study Designs

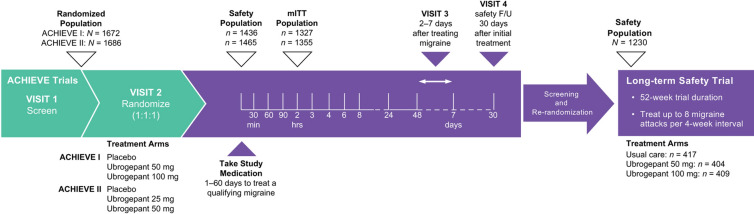

The designs of ACHIEVE I (NCT02828020), ACHIEVE II (NCT02867709), and the subsequent LTS extension trial (NCT02873221) have been previously described [19–21]. Briefly, ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II were randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-attack, phase 3 trials (Fig. 1) [19, 20]. In ACHIEVE I, participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive placebo, ubrogepant 50 mg, or ubrogepant 100 mg administered orally at the time of a qualifying migraine attack. In ACHIEVE II, participants were assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive placebo, ubrogepant 25 mg, or ubrogepant 50 mg at the time of a qualifying migraine attack. Randomization in both trials was stratified by historical triptan response and current migraine preventive medication use (yes/no). To be eligible, participants had a history of migraine (with or without aura) for at least 1 year and a history of 2–8 migraines with moderate to severe pain in each of the 3 months before screening. People with a diagnosis of chronic migraine with fewer than 15 headache days per month while taking concomitant preventive treatment were eligible to participate in both trials. Eligible participants from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II could enroll in the LTS extension trial [21]. In the LTS trial, participants were re-randomized (1:1:1) to usual care or blinded treatment with ubrogepant 50 mg or ubrogepant 100 mg and followed every 4 weeks for up to 52 weeks. Participants were allowed to treat up to 8 migraine attacks per month. Participants on a stable dose of preventive medication for migraine were allowed to continue on that medication in the LTS trial.

Fig. 1.

Trial schemas. F/U, follow-up; mITT, modified intent-to-treat [19–21]

All trials were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments and the International Council for Harmonisation’s Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. Institutional review board approval was obtained for each trial protocol. All participants provided written informed consent. All authors had full access to the trial data.

Study Assessments and Outcomes

Efficacy was based on participant-reported ratings (no, mild, moderate, or severe) of pain related to headache and non-headache symptoms associated with migraine (photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, vomiting) at prespecified time points before and after treatment administration. In the ACHIEVE trials, the coprimary endpoints included pain freedom and absence of most bothersome symptom (MBS) at 2 h after ubrogepant administration. A key secondary endpoint was pain relief at 2 h after ubrogepant administration.

In the LTS trial, investigators probed for treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and estimated the severity of events at each trial visit. TEAEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 20.1.

Statistical Analysis

In this post hoc analysis, efficacy endpoints (from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II) and safety outcomes (from the LTS trial) were compared between participants with any prior (6 months before screening) or current concomitant preventive medication use for migraine and those without preventive medication use. Preventive medications included anticonvulsants (topiramate, valproic acid, divalproex sodium), beta blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, timolol, atenolol, nadolol), antidepressants (amitriptyline, venlafaxine), and onabotulinumtoxinA. Any participant with reported current or prior use of preventive medication was included in the preventive subgroup. To improve precision for estimates of efficacy outcomes in these smaller subgroups, data from the 50 mg groups from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II were pooled and compared with pooled data from the placebo groups in ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II. Data from the 100 mg dose group in ACHIEVE I were compared with data from the placebo group in ACHIEVE I to evaluate the 100 mg dose.

Analyses of efficacy outcomes were based on the ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II modified intent-to-treat populations (all randomized participants who received at least one dose of study medication, recorded a baseline migraine headache severity measurement, and had at least one postdose migraine headache severity or migraine-associated measurement at or before the 2-h time point). Responder rates for each outcome were calculated as the percentage of participants achieving response criteria for each outcome. Percentages were calculated as 100 × (n/N1). Differences between treatment groups were evaluated using a two-sided Fisher exact test (p < 0.05). The last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach was used for the imputation of missing post-treatment values. All statistical analyses were calculated using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

To increase the likelihood of detecting lower-frequency events in the safety analysis, data from participants in the safety populations (all randomized participants who received at least one dose of study medication) in the 50 mg and 100 mg dose groups from the LTS trial were pooled. This combined sample size (n = 813) provided us with at least a 92% probability of observing an adverse event with an incidence rate of 0.31% or higher.

Results

Participants

A total of 2247 participants from the ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trials were included in this pooled analysis of efficacy. Of these, 18.6% (417/2247) reported preventive medication use. Of 813 participants in the LTS trial who were included in the safety analysis, 17.5% (143/813) reported preventive medication use. Across groups, most participants were female (range 85.1–93.3%), most were white (range 80.5–93.2%), and mean age ranged from 39.9 to 44.7 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline

| ACHIEVE trials (N = 2247)a | LTS trial (N = 813)b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo POOLED | Ubrogepant 50 mg POOLED |

Ubrogepant 100 mg ACHIEVE I |

Ubrogepant 50 mg and 100 mg POOLED | |||||

| With preventive (n = 180) | Without preventive (n = 732) | With preventive (n = 164) | Without preventive (n = 723) | With preventive (n = 73) | Without preventive (n = 375) | With preventive (n = 143) | Without preventive (n = 670) | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 43.5 (11.4) | 40.5 (12.0) | 42.8 (11.2) | 39.9 (12.2) | 43.7 (12.2) | 39.7 (12.0) | 44.7 (11.2) | 41.3 (11.8) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 160 (88.9) | 649 (88.7) | 153 (93.3) | 650 (89.9) | 67 (91.8) | 319 (85.1) | 133 (93.0) | 606 (90.4) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| White | 163 (90.6) | 591 (80.7) | 146 (89.0) | 582 (80.5) | 68 (93.2) | 304 (81.1) | 127 (88.8) | 560 (83.6) |

| Black/African American | 13 (7.2) | 113 (15.4) | 16 (9.8) | 119 (16.5) | 5 (6.8) | 58 (15.5) | 14 (9.8) | 92 (13.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 9 (5.0) | 123 (16.8) | 13 (7.9) | 133 (18.4) | 3 (4.1) | 43 (11.5) | 9 (6.3) | 111 (16.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 29.4 (7.3) | 30.0 (7.7) | 29.6 (7.8) | 30.5 (7.8) | 27.3 (6.3) | 31.2 (8.2) | 28.6 (7.7) | 30.0 (7.6) |

| Duration of migraine, mean (SD), years | 21.6 (13.0) | 18.5 (12.3) | 20.2 (12.2) | 17.4 (12.0) | 20.1 (12.5) | 18.7 (12.2) | 21.0 (12.7) | 18.4 (11.4) |

| Frequency of moderate/severe headaches in previous 3 months, n (%) | ||||||||

| 2–4 attacks/month | 94 (52.2) | 432 (59.0) | 80 (48.8) | 425 (58.8) | 34 (46.6) | 211 (56.3) | 66 (46.2) | 405 (60.4) |

| 5–8 attacks/month | 86 (47.8) | 300 (41.0) | 84 (51.2) | 298 (41.2) | 39 (53.4) | 164 (43.7) | 77 (53.8%) | 265 (39.6) |

| Preventive medications, n (%) | ||||||||

| Anticonvulsants | 91 (50.5) | 0 | 85 (51.8) | 0 | 32 (43.8) | 0 | 71 (49.7) | 0 |

| Beta blockers | 28 (15.6) | 0 | 27 (16.5) | 0 | 15 (20.5) | 0 | 26 (18.2) | 0 |

| Antidepressants | 37 (20.6) | 0 | 43 (26.2) | 0 | 13 (17.8) | 0 | 35 (24.5) | 0 |

| OnabotulinumtoxinA | 57 (31.7) | 0 | 36 (22.0) | 0 | 21 (28.8) | 0 | 42 (29.4) | 0 |

BMI body mass index, LTS long-term safety, SD standard deviation

aModified intent-to-treat population. Data from the ubrogepant 25 mg group were not included in this analysis

bSafety population. Because of the small subgroup sample sizes, data from both ubrogepant treatment arms (50 mg and 100 mg) were combined for this analysis

Clinical characteristics were generally similar across groups. The severity of the treated attack in the ACHIEVE trials was similar between participants with and without preventive medication use.

Efficacy Results (ACHIEVE Trials)

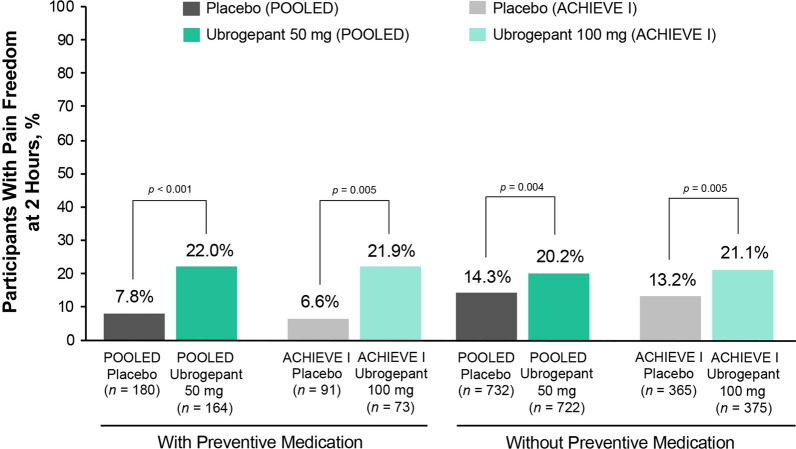

Within all dose and preventive medication subgroups, pain freedom at 2 h was significantly greater in participants receiving ubrogepant compared with those randomized to placebo (p ≤ 0.005) (Fig. 2). Within each dose group, responder rates for pain freedom did not significantly differ between ubrogepant participants with or without preventive medication use (p > 0.05) (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material).

Fig. 2.

Pain freedom response rates at 2 h after ubrogepant administration between participants with and without preventive treatment. The percentage of participants achieving pain freedom at 2 h after ubrogepant administration is shown for participants receiving placebo in both ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II (POOLED data; dark gray bars) or in ACHIEVE I only (light gray bars), for participants receiving ubrogepant 50 mg in both ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II (POOLED data; dark green bars), or ubrogepant 100 mg in ACHIEVE I only (light green bars) for participants who were taking preventive medication (left bars) or not (right bars). p values are based on Fisher exact test, two-tailed, vs placebo

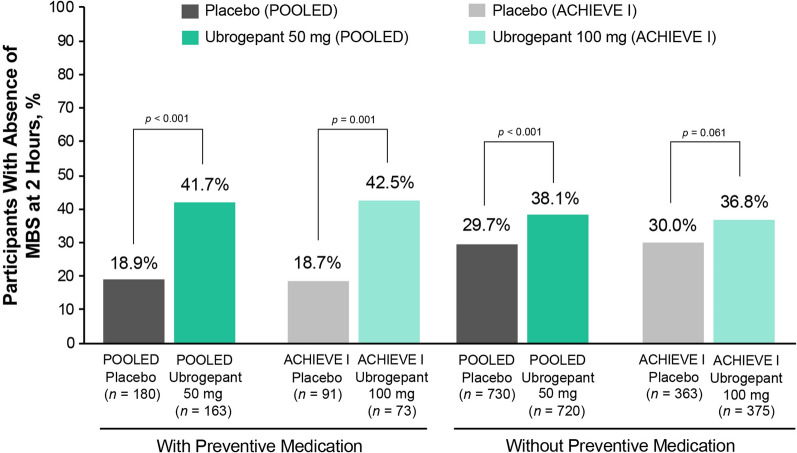

Significantly more participants receiving ubrogepant 50 mg achieved absence of MBS at 2 h compared with placebo participants in both the preventive and without preventive medication subgroups (Fig. 3; p ≤ 0.001). For participants randomized to ubrogepant 100 mg, a significantly greater absence of MBS response rate compared with placebo was observed in those with preventive medication use (p = 0.001); however, the difference from placebo in the without preventive medication subgroup did not reach significance (p = 0.061). Within each dose group, responder rates for absence of MBS did not significantly differ between ubrogepant participants with or without preventive medication use (p > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Absence of MBS response rates at 2 h after ubrogepant administration between participants with and without preventive treatment. The percentage of participants achieving absence of MBS at 2 h after ubrogepant administration is shown for participants receiving placebo in both ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II (POOLED data; dark gray bars) or in ACHIEVE I only (light gray bars), for participants receiving ubrogepant 50 mg in both ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II (POOLED data; dark green bars), or ubrogepant 100 mg in ACHIEVE I only (light green bars) for participants who were taking preventive medication (left bars) or not (right bars). p values are based on Fisher exact test, two-tailed, vs placebo. MBS, most bothersome symptom

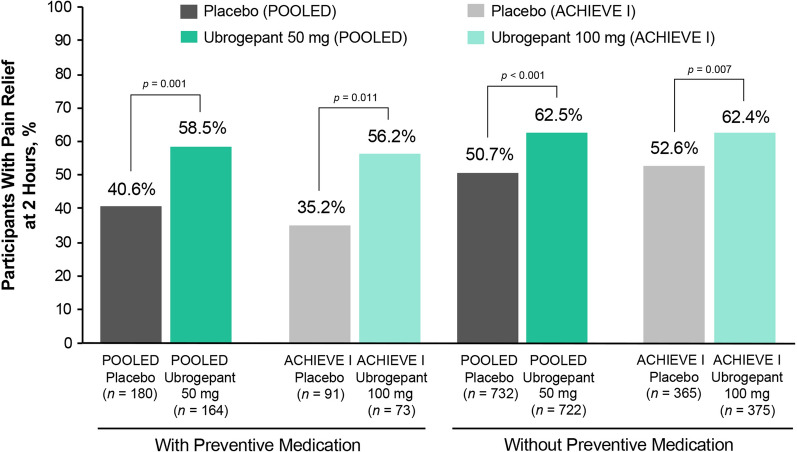

Similarly, ubrogepant use was associated with significantly higher rates of pain relief at 2 h after administration compared with placebo (p ≤ 0.011) (Fig. 4). Within each dose group, responder rates for pain relief did not significantly differ between ubrogepant participants with or without preventive medication use (p > 0.05). A numerically greater therapeutic gain (i.e., difference in responder rates between ubrogepant and placebo) was observed among participants receiving ubrogepant with preventive medications for migraine than among those without preventive medications across all efficacy outcomes. Treatment differences between ubrogepant and placebo in the LTS trial were generally similar to those observed in ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II.

Fig. 4.

Pain relief response rates at 2 h after ubrogepant administration between participants with and without preventive treatment. The percentage of participants achieving pain freedom at 2 h after ubrogepant administration is shown for participants receiving placebo in both ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II (POOLED data; dark gray bars) or in ACHIEVE I only (light gray bars), for participants receiving ubrogepant 50 mg in both ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II (POOLED data; dark green bars), or ubrogepant 100 mg in ACHIEVE I only (light green bars) for participants who were taking preventive medication (left bars) or not (right bars). p values are based on Fisher exact test, two-tailed, vs placebo

Safety Results (LTS Trial)

In the safety analysis of the LTS trial, the percentage of participants with at least one TEAE was similar between participants with or without preventive medications (Table 2). Rates of treatment-related TEAEs, serious adverse events (SAEs), and TEAEs leading to discontinuation were similar between groups, and no treatment-related SAEs were reported during the trial. The most common TEAEs that occurred in at least 2% of participants and more commonly than in placebo participants in the ACHIEVE trials were nausea, somnolence, and dry mouth (Table 2). The most common overall TEAE in the LTS trial was upper respiratory tract infection, which was reported by 11.2% of participants with (16/143) or without (75/670) preventive medications (see Table S1 in the supplementary material). No clinically relevant changes in vital signs were observed. No differences were observed between the safety profiles of the 50 mg and 100 mg ubrogepant groups.

Table 2.

Summary of safety in participants who received ubrogepant with or without preventive medication

| Participants with event, n (%) | With preventivea (n = 143) |

Without preventiveb (n = 670) |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 1 TEAE | 105 (73.4) | 457 (68.2) |

| ≥ 1 Treatment-related TEAE | 11 (7.7) | 74 (11.0) |

| ≥ 1 SAE | 5 (3.5) | 14 (2.1) |

| ≥ 1 Treatment-related SAE | 0 | 0 |

| ≥ 1 TEAE leading to discontinuation | 4 (2.8) | 16 (2.4) |

| Common TEAEsc | ||

| Dry mouth | 1 (0.7) | 5 (0.7) |

| Nausea | 7 (4.9) | 32 (4.8) |

| Somnolence | 3 (2.1) | 8 (1.2) |

Safety data pooled across ubrogepant 50 mg and 100 mg dose groups in the LTS trial

LTS long-term safety, SAE serious adverse event, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

aOnly participants who received ubrogepant and also took any preventive treatment (including anticonvulsants, beta blockers, antidepressants, and onabotulinumtoxinA) as prior and concomitant medication during the trial are included. Only TEAEs that occurred on or after the randomization date and on or before the date of last preventive dose + 30 days are included

bOnly participants who received ubrogepant and did not take any preventive treatment as prior and concomitant medication during the trial are included. Only TEAEs that occurred on or after the randomization date are included

cTEAEs occurring in at least 2% and at a frequency greater than placebo in ACHIEVE trials

Discussion

In this analysis of pooled efficacy data from the ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trials, responder rates for pain freedom, absence of MBS, and pain relief at 2 h after ubrogepant administration were significantly higher compared with placebo. Additionally, responder rates were not significantly different between participants with or without preventive medication use. Furthermore, data from the LTS extension trial showed that the safety profile of ubrogepant was similar between participants with or without preventive medication use.

Individuals with migraine who take preventive medications may represent a more severely affected subgroup because of greater attack frequency or severity, or both. Because of these factors, it is unclear whether acute treatment efficacy would differ for these individuals; however, our results show that ubrogepant was associated with significant efficacy in people with migraine regardless of preventive medication use, and no safety concerns were identified in the preventive use subgroup. Although it has been anecdotally reported that people with migraine on successful preventive treatment regimens have improved response to acute medications [10], within each ubrogepant dose group, we did not observe any significant differences between the preventive treatment groups for any efficacy outcome. Although the study was not designed to compare efficacy by preventive use status, the subgroup sample size for the pooled ACHIEVE 50 mg dose did include more than 150 participants who reported preventive use. In addition, there may be other reasons why an improvement in efficacy was not observed. First, ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II were single-attack trials. Improvements in efficacy of acute treatment with preventive use may be more evident over multiple attacks where acute treatment was used. Second, compliance to concomitant preventive medication use was not assessed during the ACHIEVE trials, and we cannot rule out that participants may not have been taking the medication regularly. Efficacy of the preventive treatment for each participant was not assessed. Although ubrogepant responder rates did not significantly differ between preventive use subgroups, the level of therapeutic gain was higher among participants receiving ubrogepant who were taking preventive medications for migraine than among those not taking preventive medications.

Across all three efficacy measures, the percentage of placebo responders was lower in the preventive medication subgroup than in the subgroup not using preventive medications, resulting in a difference in therapeutic gain. This effect has been observed in other recent clinical trials of acute treatment medications for migraine [22]. In a pooled analysis of lasmiditan, 698 of 3981 (17.5%) participants reported use of preventive medications [22]. For the outcomes of pain freedom and absence of MBS at 2 h, significant differences from placebo were observed for nearly all dose groups, regardless of preventive medication use. Notably, the placebo response rates for the preventive medication subgroup were lower compared with the response rates for those not using preventives for pain freedom at 2 h (11.7% vs 19.8%) and absence of MBS at 2 h (23.8% vs 33.3%).

When selecting a combination of acute and preventive medications for an individual with migraine, the occurrence of adverse events is an important consideration [23]. One common reason for the development of adverse events with concomitant therapies is drug–drug interactions, which may impact medication tolerability and treatment effectiveness [23]. Drug–drug interactions with headache medications can be more common with medications metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system [24], and this must be taken into consideration when selecting a comprehensive treatment regimen for an individual with migraine [25]. Ubrogepant is metabolized by the CYP3A4 hepatic pathway, and some medications that may be used for migraine prevention can inhibit or induce this pathway [9, 26]. Topiramate, a commonly used preventive medication, is an inducer of CYP3A4 [27] and could reduce ubrogepant exposure and efficacy when topiramate and ubrogepant are used concomitantly. The sample size of ACHIEVE trial participants reporting use of topiramate was not large enough to make meaningful conclusions about efficacy in this subgroup; however, ubrogepant prescribing information recommends that those who use topiramate or any other weak CYP3A4 inducer should increase their dose of ubrogepant to 100 mg [11]. In addition, pharmacokinetic data on the impact of ubrogepant on CGRP-targeted monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have not shown any interactions [28]. Consistent with the safety results reported here, ubrogepant has minimal pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions overall [13, 29, 30]. The results of this study indicate that ubrogepant is safe to use with the preventive medications for migraine and can be applied when being used in real-world practice.

Many people with migraine, particularly those with chronic migraine, have a potential complicating factor of medication overuse headache (MOH). Ubrogepant does not have a warning for MOH in its US Food and Drug Administration labeling [11]. Additionally, a preclinical MOH study found that repeated treatment with ubrogepant did not induce cutaneous allodynia or latent sensitization in an animal model, suggesting that ubrogepant may offer effective acute treatment of migraine without the potential risk of MOH [31]. Risk of MOH should be an additional factor taken into consideration when choosing an acute medication option in individuals with frequent attacks sufficient to warrant the use of preventive medications.

There are a number of limitations to this study. This was a post hoc subgroup analysis of the ACHIEVE trials and the LTS extension trial. The study was not designed to assess differences in ubrogepant efficacy among participants based on preventive medication use statistics. This post hoc analysis did not include a generalized linear mixed model approach and did not include correction for multiple comparisons. The subgroups of participants taking preventive medications in ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II were small, and comparisons of efficacy and safety should therefore be made with caution. Additionally, because of the smaller sample sizes of participants taking specific classes of preventive medications, safety and efficacy of ubrogepant with preventive medication classes could not be assessed. Efficacy outcomes were based on single attacks, and the consistency of response across multiple attacks is unclear. Alternatively, whether the efficacy of acute treatment in those taking a preventive medication may improve over multiple attacks could not be assessed. The efficacy and safety of ubrogepant administered with erenumab, a mAb against the CGRP receptor, were not evaluated in this study. Because erenumab has a label warning about development or worsening of hypertension [32], physicians should carefully monitor blood pressure when ubrogepant is used in combination with a CGRP-targeted mAb.

The study benefited from a large overall sample size with the pooling of data between ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II. Additionally, the inclusion of participants who were taking preventive medications is in alignment with real-world practice.

Conclusion

Ubrogepant demonstrated efficacy in participants who did and did not report preventive medication use. Long-term dosing of ubrogepant in participants with preventive medication use (including anticonvulsants, beta blockers, antidepressants, and onabotulinumtoxinA) was safe and well tolerated, with no clinically meaningful effect on ubrogepant efficacy. No new safety signals emerged with the use of ubrogepant as an acute treatment for migraine when taken with concomitant preventive medications.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees were funded by Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie).

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided to the authors by Cory R. Hussar, PhD, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, Parsippany, NJ, and was funded by AbbVie.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

Study Concept and Design

Aubrey Manack Adams, Lawrence Severt, Matthew Butler, David W. Dodick.

Acquisition of Data

Kerry Knievel.

Analysis and Interpretation of Data

All authors.

Drafting the Manuscript

None for this manuscript.

Revising the Manuscript for Intellectual Content

All authors.

Final Approval of the Completed Manuscript

All authors.

Prior Presentation

This manuscript is based in part on work that has been previously presented at the 2020 American Academy of Neurology Science Highlights Virtual Platform, May 2020; the 2020 American Headache Society Virtual Annual Scientific Meeting (62nd), June 2020; the Migraine Trust Virtual Symposium, October 3–9, 2020; the 14th Annual Headache Cooperative of the Pacific Virtual Winter Conference, January 29–30, 2021.

Disclosures

Andrew M. Blumenfeld has served on advisory boards for, consulted for, and/or been a speaker or contributing author for AbbVie, Aeon, Alder, Amgen, Biohaven, Equinox, Impel, Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, Promius, Revance, Teva, Theranica, and Zoscano. He has received grant support from AbbVie and Amgen. Kerry Knievel has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Axsome, Biohaven, Eli Lilly, and Theranica; conducted research with AbbVie, Amgen, and Eli Lilly; and is on speaker programs with AbbVie and Amgen. David W. Dodick reports the following conflicts within the past 12 months: Consulting: AbbVie, AEON, Amgen, Clexio, Cerecin, Ctrl M, Allergan, Alder, Biohaven, Linpharma, Lundbeck, Promius, Eli Lilly, eNeura, Novartis, Impel, Satsuma, Theranica, Vedanta, WL Gore, Nocira, XoC, Zosano, Upjohn (Division of Pfizer), Pieris, Revance, Equinox. Honoraria: CME Outfitters, Curry Rockefeller Group, DeepBench, Global Access Meetings, KLJ Associates, Academy for Continued Healthcare Learning, Majallin LLC, Medlogix Communications, MJH Lifesciences, Miller Medical Communications, Southern Headache Society (MAHEC), WebMD Health/Medscape, Wolters Kluwer, Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press. Research Support: US Department of Defense, National Institutes of Health, Henry Jackson Foundation, Sperling Foundation, American Migraine Foundation, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Stock Options/Shareholder/Patents/Board of Directors: Ctrl M (options), Aural Analytics (options), ExSano (options), Palion (options), Healint (options), Theranica (options), Second Opinion/Mobile Health (options), Epien (options/board), Nocira (options), Matterhorn (shares/board), Ontologics (shares/board), King-Devick Technologies (options/board), Precon Health (options/board). Patent 17189376.1-1466:vTitle: Botulinum Toxin Dosage Regimen for Chronic Migraine Prophylaxis. Aubrey Manack Adams, Lawrence Severt, Matthew Butler, and Hongxin Lai are employees of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All trials were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments and the International Council for Harmonisation’s Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. Institutional review board approval was obtained for each trial protocol. All participants provided written informed consent. All authors had full access to the trial data.

Data Availability

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

References

- 1.Pietrobon D, Moskowitz MA. Pathophysiology of migraine. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:365–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Headache disorders. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2016. http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/headache-disorders. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

- 3.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68(5):343–349. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Silberstein SD. Migraine symptoms: results of a survey of self-reported migraineurs. Headache. 1995;35(7):387–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3507387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goadsby PJ, Holland PR. An update: pathophysiology of migraine. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(4):651–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2019.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Headache Society The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59(1):1–18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silberstein SD. Preventive migraine treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21(4 Headache):973–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Curto M, Capi M, Cipolla F, Cisale GY, Martelletti P, Lionetto L. Ubrogepant for the treatment of migraine. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21(7):755–759. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2020.1721462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loder E, Rizzoli P. Pharmacologic prevention of migraine: a narrative review of the state of the art in 2018. Headache. 2018;58(Suppl 3):218–229. doi: 10.1111/head.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ubrelvy [package insert]. Madison, NJ: Allergan USA, Inc. 2020.

- 12.Moore E, Fraley ME, Bell IM, et al. Characterization of ubrogepant: a potent and selective antagonist of the human calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2020;373(1):160–166. doi: 10.1124/jpet.119.261065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blumenfeld AM, Edvinsson L, Jakate A, Banerjee P. Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of ubrogepant: a potent, selective calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist for the acute treatment of migraine. J Fam Pract. 2020;69(1 suppl):S8–S12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Do TP, Guo S, Ashina M. Therapeutic novelties in migraine: new drugs, new hope? J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-0974-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piccinni C, Cevoli S, Ronconi G, et al. A real-world study on unmet medical needs in triptan-treated migraine: prevalence, preventive therapies and triptan use modification from a large Italian population along two years. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1027-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipton RB, Buse DC, Serrano D, Holland S, Reed ML. Examination of unmet treatment needs among persons with episodic migraine: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache. 2013;53(8):1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/head.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipton RB, Hutchinson S, Ailani J, et al. Discontinuation of acute prescription medication for migraine: results from the chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache. 2019;59(10):1762–1772. doi: 10.1111/head.13642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Messali AJ, Yang M, Gillard P, et al. Treatment persistence and switching in triptan users: a systematic literature review. Headache. 2014;54(7):1120–1130. doi: 10.1111/head.12404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ailani J, et al. Ubrogepant for the treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(23):2230–2241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Effect of ubrogepant versus placebo on pain and the most bothersome associated symptom in the acute treatment of migraine: the ACHIEVE II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(19):1887–1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ailani J, Lipton RB, Hutchinson S, et al. Long-term safety evaluation of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: phase 3, randomized, 52-week extension trial. Headache. 2020;60(1):141–152. doi: 10.1111/head.13682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loo LS, Ailani J, Schim J, et al. Efficacy and safety of lasmiditan in patients using concomitant migraine preventive medications: findings from SAMURAI and SPARTAN, two randomized phase 3 trials. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1032-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lionetto L, Borro M, Curto M, et al. Choosing the safest acute therapy during chronic migraine prophylactic treatment: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2016;12(4):399–406. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2016.1154042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ansari H, Ziad S. Drug-drug interactions in headache medicine. Headache. 2016;56(7):1241–1248. doi: 10.1111/head.12864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pomes LM, Guglielmetti M, Bertamino E, Simmaco M, Borro M, Martelletti P. Optimising migraine treatment: from drug-drug interactions to personalized medicine. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1010-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh A, Gupta D, Sahoo AK. Acute migraine: can the new drugs clinically outpace? SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2(8):1132–1138. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00390-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Topamax [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2019.

- 28.Jakate A, Blumenfeld AM, Boinpally R, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of ubrogepant when coadministered with calcitonin gene-related peptide-targeted monoclonal antibody migraine preventives in participants with migraine: a randomized phase 1b drug-drug interaction study. Headache. 2021;61(4):642–652. doi: 10.1111/head.14095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C, Palcza J, Xu J, et al. The effect of multiple doses of ubrogepant on the pharmacokinetics of an oral contraceptive in healthy women: results of an open-label, single-center, two-period, fixed-sequence study. Cephalalgia Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1177/2515816320905082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jakate A, Boinpally R, Butler M, et al. Evaluation of the pharmacokinetic interaction and safety of ubrogepant coadministered with acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a randomized trial. Cephalalgia Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1177/2515816320921186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navratilova E, Behravesh S, Oyarzo J, Dodick DW, Banerjee P, Porreca F. Ubrogepant does not induce latent sensitization in a preclinical model of medication overuse headache. Cephalalgia. 2020;40:892–902. doi: 10.1177/0333102420938652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aimovig [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA, and East Hanover, NJ: Amgen Inc., and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.