Abstract

Leclercia adecarboxylata was isolated from a patient with a chronically inflamed gallbladder, together with Enterococcus sp. The organism was considered clinically significant and was susceptible to all antibiotics tested. Another strain of L. adecarboxylata was cultured from blood, together with Escherichia hermannii and E. faecalis, from a patient with sepsis.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1.

In 1999 a 78-year-old female was admitted to the Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium, with acute severe abdominal pain and biochemistry compatible with cholecystitis and oedomatous biliary pancreatitis (Ranson score 6), for which an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) with papillotomy was performed. She was admitted again 3 months later for an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy to prevent further evolution of a pancreatitis. During hospitalization Candida albicans sepsis with pneumonia as the focus was diagnosed, and treatment with imipenem (1 g, three times per day) and fluconazole (400 mg, once daily) was started. Imipenem was given prophylactically during ERCP. The patient recovered and was sent home 5 weeks later. A follow-up scan of the pancreas and an abdominal echography showed pseudocysts and cholecystolithiasis, leading to elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy, whereafter the patient was cured.

Pathologic examination of the gallbladder confirmed the chronic inflammation. Gram staining of the specimen revealed streptococci and gram-negative bacilli. Bacteriologic culture of the gallbladder tissue on blood agar (tryptic soy agar with 5% sheep blood), MacConkey agar, mannitol salt agar, and thioglycolate broth (all from Becton Dickinson BBL, Erembodegem, Belgium) yielded enterococci and a gram-negative rod. The isolates were considered clinically significant. The gram-negative isolate produced lactose-positive, yellowish colonies with a typical odor for Escherichia coli. The following tests were positive: motility, β-glucosidase, indole production, glucose fermentation-oxidation, amygdaline, mannitol, rhamnose, mellibiose, sucrose, and arabinose. The strain was negative for lysine decarboxylase, ornithine decarboxylase, citrate, urease, hydrogen sulfide production, oxidase, tryptophane deamination, β-glucuronidase, arginine hydrolase, Voges-Proskauer, gelatinase, inositol, and sorbitol. This led to the identification of Leclercia adecarboxylata (4, 8, 9).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing according to the Kirby-Bauer method and NCCLS criteria showed that the strain was susceptible to cotrimoxazole, amikacin, gentamicin, fluoroquinolones, ampicillin, piperacillin, temocilline, cefuroxime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, aztreonam, and imipenem.

Case 2.

An 80-year-old female cardiac patient, hospitalized at the St. Elisabeth Hospital, Brussels, Belgium, in 1995 for a fourfold coronary bypass, developed an undocumented pneumonia postoperatively, which was treated with cefotaxime, and a C. albicans sepsis, which was treated with diflucan. On postoperative day 26, the patient developed a new septic episode with shiverings and a temperature of 38°C. White blood cell and neutrophil counts were 25,900 and 24,864 cells/μl, respectively, and the C-reactive protein value was 94 mg/liter. Two sets of blood cultures, obtained 15 min apart, were positive with gram-positive cocci (identified as Enterococcus faecalis) and gram-negative rods. A focus for this sepsis could not be found. The gram-negative rods grew as two different types of yellow colonies and were identified with Vitek I (bioMérieux) and conventional biochemical tests as Escherichia hermannii and Leclercia adecarboxylata. The strain was resistant for ampicillin and susceptible for cefuroxim, ceftriaxone, aztreonam, piperacillin, imipenem, gentamicin, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, and cotrimoxazole.

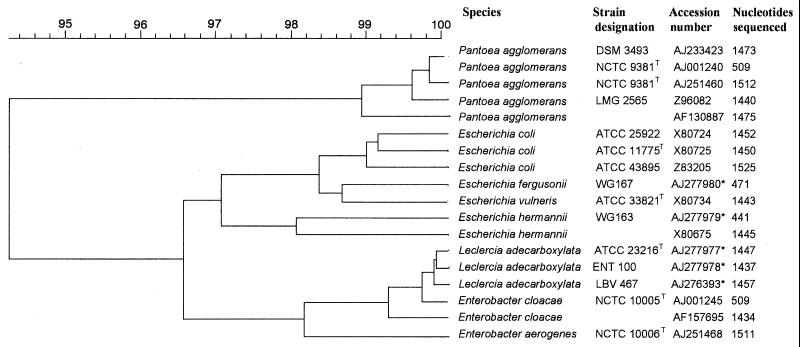

Sequence determination of the 16S rRNA gene of both strains (LBV467 and ENT100) was carried out (GenBank entries AJ276393 [1,457 bp] and AJ277978 [1,437 bp]) and revealed 98% similarity with Pantoea agglomerans (GenBank entry AB004961) as the closest match. Since no entries for L. adecarboxylata were present in GenBank, an additional determination of the 16S rRNA gene sequence of the type strain of L. adecarboxylata (ATCC 23216T) was carried out (GenBank entry AJ277977 [1,447 bp]) and revealed 99.6% identity with LBV467 and 99.8% with ENT100. Clustering with 16S rRNA gene sequences determined from Escherichia, Enterobacter, and Pantoea spp. is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram constructed using UPGMA (unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages) of the 16S rRNA sequences. Sequences determined in this study are indicated with an asterisk.

Amplification of the tRNA intergenic spacers (12) and separation of the fragments by AB1310 Prism capillary electrophoresis (11) resulted in DNA fingerprints for the three L. adecarboxylata strains in this study (ATCC 23216T, LBV467, and ENT100), having in common PCR fragments with average lengths of 74.1, 79.0, 92.1, 137.8, 189, 209.8, and 379.8 bp. A DNA fingerprint composed of tRNA spacers with these lengths was not observed for any of the 170 other gram-negative species tested and thus might be used to identify L. adecarboxylata strains.

Reports on the isolation of L. adecarboxylata, formerly known as Escherichia adecarboxylata or Enteric group 41, from environmental and clinical specimens are rare. Thus far, this species has been isolated from the blood of a patient with hepatic cirrhosis (2), from the blood of a child receiving total parenteral nutrition (7), from the blood of a patient with neutropenia (10) and from another case of bacteremia (9), in wound infections in mixed culture from lower extremities in three patients (10), from ulcer exudate (6), from another case of wound infection (9), from the sputum of a patient with pneumonia caused by multiple bacteria (10), in a case of bacterial endocarditis (3), and from the feces of three patients with diarrhea (1). In all of these cases all strains were found to be susceptible to all antibiotics tested.

Recently, Lee et al. (5) reported mixed growth of L. adecarboxylata and E. hermannii from the culture of the catheter tip and from all three sets of blood cultures taken from different peripheral veins in a case of Hickmann catheter-related bacteremia in a 69-year-old woman completing a fourth course of chemotherapy for the treatment of leiomyosarcoma. The simultaneous isolation from a blood culture of isolates from two rare gram-negative enterobacterial species, both motile and with yellow-pigmented colonies, as occurred in the 1995 case reported here, is surprising. Even more surprising is that this coisolation from blood culture was reported to have occurred elsewhere (5). In both of the cases reported here enterococci were also cultured together with L. adecarboxylata.

We report the isolation of L. adecarboxylata in mixed culture with enterococci from a peroperative sample of a chronically inflamed gallbladder and the isolation of L. adecarboxylata together with E. hermannii and E. faecalis from the blood cultures of a septic episode without focus. The isolates were considered clinically significant. Identification of L. adecarboxylata by means of biochemical testing and tRNA-PCR is unambiguous. We want to draw attention to the fact that a rather unlikely event such as the coisolation of two rarely cultured yellow pigmented Enterobacteriaceae was reported twice independently.

Acknowledgments

We thank Leen Van Simaey and Marleen Regent for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cai M, Dong X, Yang F, Xu D, Zhang H, Zheng X, Wang S, Jin H. Isolation and identification of Leclercia adecarboxylata in clinical specimens in China. Wei Sheng Wu Hsueh Pao. 1992;32:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daza R M, Iborra J, Alonso N, Vera I, Portero F, Mendaza P. Isolation of Leclercia adecarboxylata in a cirrhotic patient. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1993;11:53–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dudkiewicz B, Szewczyk E. Etiology of bacterial endocarditis in materials from cardiology and cardiac surgery clinics of the Lodz Academy. Med Dosw Mikrobiol. 1993;45:357–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leclerc H. Etude biochimique d'Enterobacteriaceae pigmentées. Ann Inst Pasteur. 1962;102:726–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee N Y, Ki C-S, Kang W K, Peck K R, Kim S, Song J-H. Hickman catheter-associated bacteremia by Leclercia adecarboxylata and Escherichia hermannii: a case report. Korean J Infect Dis. 1999;31:167–170. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez M M, Sanchez G, Gomez J, Mendaza P, Daza R M. Isolation of Leclercia adecarboxylata in ulcer exudate. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1998;16:345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otani E, Bruckner D A. L. adecarboxylata isolated from blood culture. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 1991;13:157–158. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richard C. Nouvelles Enterobacteriaceae rencontrées en bactériologie médicale: Moelerella wisconsis, Koserella trabulsii, Leclercia adecarboxylata, Escherichia fergusonii, Enterobacter asburiae, Rahnella aquatilis. Ann Biol Clin. 1989;37:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamura K, Sakazaki R, Kosako Y, Yoshizaki E. Leclercia adecarboxylata gen. nov., comb. nov., formerly known as Escherichia adecarboxylata. Curr Microbiol. 1986;13:179–184. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temesgen Z, Toal D R, Cockerill F R., III Leclercia adecarboxylata infections: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;25:79–81. doi: 10.1086/514514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaneechoutte M, Boerlin P, Tichy H-V, Bannerman E, Jäger B, Bille J. Comparison of the value of DNA-fingerprinting techniques for the identification and taxonomical classification of Listeria species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:127–139. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-1-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welsh J, McClelland M. Genomic fingerprints produced by PCR with consensus tRNA gene primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:861–866. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.4.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]