Abstract

Purpose

There have been few studies using mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) to improve sexual function in Asian women with breast cancer. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of mindfulness intervention on female sexual function, mental health, and quality of life in patients with breast cancer.

Methods

Fifty-one women with breast cancer were allocated into 6-week MBSR (n=26) sessions or usual care (n=25), without differences in group characteristics. The research tools included the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21), and the EuroQol instrument (EQ-5D). The Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS) was used to verify the foregoing scale. The effects of MBSR were evaluated by the differences between the post- and pre-intervention scores in each scale. Statistical analyses consisted of the descriptive dataset and Mann-Whitney ranked-pairs test.

Results

Although MBSR did not significantly improve sexual desire and depression in patients with breast cancer, MBSR could improve parts of female sexual function [i.e., Δarousal: 5.73 vs. -5.96, Δlubrication: 3.35 vs. -3.48, and Δsatisfaction: 8.48 vs. 1.76; all p <.005], with a range from small to medium effect sizes. A significantly benefits were found on mental health [Δanxiety: -10.92 vs.11.36 and Δstress: -10.96 vs.11.40; both p <.001], with large effect sizes, ranging from 0.75 to 0.87.

Conclusion

Our study revealed that MBSR can improve female sexual function and mental health except for sexual desire and depression in women with breast cancer. Medical staff can incorporate MBSR into clinical health education for patients with breast cancer to promote their overall quality of life.

Keywords: Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), Breast cancer, Sexual function, Psychological benefit, Quality of life

Introduction

Among cancers, breast cancer is the most prevalent among women and has the second-highest mortality rate in Taiwan [1]. The vast majority of patients with breast cancer receive surgery and adjuvant treatment, and iatrogenic menopause or estrogen deprivation therapy in the treatment of female breast cancer can adversely affect sexual function [2]. The literature shows that female patients with breast cancer are subject to changes in sexual function, body image, sexual activity, and intimacy after treatment [3]. After experiencing menopausal symptoms and changes in sexual function, patients with breast cancer can feel distressed, frustrated, helpless, and psychologically burdened [4].

In recent years, there were only a few international studies on breast cancer, sexual function, and sexual dysfunction. Young breast cancer survivors and their partners recruited by Price Blackshear and other experimenters were randomly assigned to an 8-week Mindfulness-Based Intervention levels of perceived stress, anxiety, depression, and fatigue were lower after the intervention [5]. Bober and other researchers examined twenty young breast cancer survivors with sexual dysfunction. The participants had received a single 4-h group intervention that included sexual health rehabilitation, body awareness exercises, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) skills. The outcome illustrated that improvements in sexual functioning and psychological distress were observed after 2 months post-intervention [6]. Other studies also summarize the literature on mechanisms of mindfulness interventions in female sexual dysfunction (FSD), and conclude that trait mindfulness and decentering are the most common mechanisms identified for the efficacy of mindfulness and the identified mediators of improvement (i.e., interoceptive awareness, depression, and trait mindfulness) when making decisions about which patient might be more likely to benefit from a mindfulness-based approach to treating sexual dysfunction [7]. There have been some studies adopting integrated approaches to examine the efficacy of an online, 12-week psychoeducational program, which included elements of mindfulness meditation, for sexual difficulties in survivors of colorectal or gynecologic cancer. The study found out that those women experienced significant improvements in sex-related distress, sexual function, and mood; these results had sustained during the six-month follow-up [8]. In Iranian, women with breast cancer received eight-session MBSR, significant statistical improvements were noted in the intervention group for sexual desire (P = 0.021) and arousal (P = 0.021) [9]. However, few studies have focused on women with breast cancer in Asia and on how mindfulness intervention can improve their sexual function and alleviate their menopausal symptoms.

In the other indicators section, many studies have applied mindfulness-based intervention to improve the quality of life of cancer patients who suffer from many annoying symptoms in the way of their psychological and physiological health as well as their physical activities. In a meta-analysis of 11 papers, Chang et al. (2020) reported that at the end of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) intervention, only depression (standardized mean difference, −1.32; 95% confidence interval [CI], −2.18 to −0.46; I2 = 97%) and fatigue symptoms (mean difference [MD], −0.47; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.34; I2 = 0%) were significantly reduced. In addition, the patients’ stress (MD, −0.79; 95% CI, −1.34 to −0.24; I2 = 0%) was significantly decreased within 3 months from the commencing date. Other indicators such as anxiety, stress, pain, and sleep quality were not observed to have a significant change [10]. However, in other international researches, Lengacher et al. (2018) implemented a single-group study with a pre- and posttest design, with a 6-week, 2-h weekly MBSR intervention. Participants were required to use an iPad app to practice mindfulness for 15–45 min daily and to record how long they had practiced. After 6 weeks, the patients with breast cancer exhibited improvements in depression, anxiety, stress, fear of cancer recurrence, sleep quality, fatigue, and life span [11]. Bisseling et al. (2017) employed a mixed-method design for an 8-consecutive-week, 2.5-h-weekly mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) intervention to improve patients’ physical and emotional quality of life, well-being, mindfulness skills, and self-compassion. Among these factors, only rumination and global quality of life did not significantly improve. This may be attributable to the deterioration of mindfulness skills after treatment; when time as a moderating variable was added to the analysis, emotional functioning and well-being became insignificant [12]. In the qualitative interview stage, the following three themes were determined to comprise one overarching theme: participation during anticancer treatment, participation after anticancer treatment, and participation in relation to emotional processing [12]. Reich et al. (2017) also reported that MBSR resulted in improvements in symptom clusters, such as anxiety, depression, perceived stress, quality of life, and fatigue, especially in the sixth week of treatment when psychological and fatigue symptoms affected patients most severely [13]. Based on the research results mentioned above, it is shown that the immediate outcome of improvement on breast cancer patients is inconsistent at the end of the MBSR program. Thus, we hypothesize that “mindfulness intervention” can improve the degree of “female sexual function” and “mental health.”

Methods

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria

Both MBSR and the usual care group were used purposive and snowball sampling. Specifically, prospective participants who visited clinics, groups, or websites on breast cancer were recruited. Patients were included only if they had a diagnosis of breast cancer within the previous 2 years at stage 0–IV; were over 20 years old; were able to communicate in Mandarin; had received at least one dose of adjuvant therapy; and had a score of ≤1 on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status scale [14]. Patients were excluded if they have been diagnosed with active psychosis or had a history of mental illness, and are currently taking antipsychotropic medications, i.e., antipsychotics or anxiolytics. However, those taking antidepressants were not excluded for a high incidence of depression in patients with active breast cancer [15]. We conducted the post-test questionnaires at the last class. If the participants were absent, we would contact them by phone to complete the surveys. If we know beforehand that they would miss the last class, we would have them fill out the post-test questionnaire in the fifth week.

Procedure

MBSR intervention

The formal practice time of this research was consisted of 6 consecutive weeks of 2-h sessions, as there was a need to spare a period of time and space to practice without any disruption. To achieve the outcome, we would like to improve mindfulness training techniques which include sitting meditation, body scan, Hatha yoga, walking mediation as well as bladder and pelvic floor muscle training. These practices were conducted either alone or in combination with other interventions) [16]. The informal practices in this study were implemented through home-based practice using a CD with meditation instruction [17]. Specifically, the participants undertook home-based practices at least 10–15 min daily, 5–6 times per week, and they recorded their personal experience on a sheet of paper. In brief, informal exercises refer to exercises without sparing specific time, so they can be practiced at all times. This includes extensive self-awareness, communication, learning, and listening. Although formal exercises are more widely discussed and practiced, a better result will be expected with the supplementary informal exercises. Mindfulness-based stress reduction emphasizes applying what you have learned to daily life, learning to be sober in every moment, being fully engaged, and focusing on doing only one thing at a time. Therefore, in informal practices, there will be mindfulness waiting to see a doctor, mindfulness taking medicine, mindfulness of evaluating illness, mindfulness of conversation, mindfulness of thinking about the meaning of life, mindfulness of judging others, etc. [17, 18].

Usual care group

The inclusion and exclusion conditions of the usual care group were the same as those of the MBSR group. The usual care group occurred in parallel to MBSR. The usual care group was given the manual to deal with the syndromes and verbal education on health and hygiene. All participants were requested not to enroll in any other stress reduction programs or mind–body therapies during the course of the study. Program uniformity and best practices across cohorts were ensured by employing a certified MBSR instructor and standardization of content. We would provide additional learning programs to the usual care group participants who were interested in learning MBSR skills when the program was over.

Ethics

All appropriate procedures conducted in research involving human participants were in line with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee in Taiwan.

Data collection

During the orientation, all participants submitted their written informed consent. The two time points at which measurements of the variables were taken were when the pre- or posttest occurred. (1) Pretest: This time point was no later than the second week of the course. The baseline values were determined by responses to questions that were based on the scale in its entirety. (2) Posttest: This time point was after the end of the sixth week of the course, and a comprehensive questionnaire was completed within one week. Participants were incentivized with coupons of NT$100 and NT$200 for completing the preintervention and postintervention questionnaires, respectively. Participants in the experimental group also received a yoga mat.

Female sexual function, mental health, and quality of life measures

Main research tools

Female sexual function

The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) comprising 19 items scored on a 5–point Likert-type scale was used to measure female sexual function [19]. Scores ranged from 2 to 36, with higher FSFI scores indicating better sexual function and scores below 26.55 indicating a risk of sexual dysfunction. The FSFI was divided into six domains, namely desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. Each of the individual domains had good test–retest reliability (r = .79–.86) [19]. In this study, the FSFI Chinese scale translated by Kuo et al (2004) was employed in analyzing. This scale was first translated by the researcher, and then sexology experts and clinicians were invited to conduct expert validity (Kuo MC et al., 2004). There is not a cut-off point score in the current Taiwan version of the scale. Therefore, we did not apply the cut-off point score for analysis. It highlighted the fact that the higher the scores of a patient, the better the sexual function status was, and vice versa.

Depression, anxiety, and stress

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) were divided into 21 items under the 3 axes of depression, anxiety, and stress; the scale measured the mental health of the participants over the past week on a 3-point Likert-type scale from 0 (never) to 3 (almost always) [20]. Anxiety, depression, or stress were scored as 21 points, and then multiplied the number of test scores by 2, which would range from 0 to 126 points. The higher the scores, the higher the level of the anxiety, depression, or stress index would be, and vice versa [20] . The DASS scales had a 0.81 and 0.74 correlation coefficient with the Beck Anxiety Inventory, respectively [20]. The Chinese version of this study adopts the version translated by Wei, Cooke, Moyle & Creedy (2008) [21], which was out of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, developed by Lovibond & Lovibond (1995). The Chinese version of the scale was evaluated in an Australian immigrant sample (n = 356) and compared to the English version of the DASS (n = 720). Confirmatory factor analysis displayed that the Chinese DASS-21 discriminates between depression, anxiety, and stress. Currently, this version prevails worldwide.

Quality of life

The EQ-5D tool was developed and is widely used in Europe to assess the general quality of life. It covers the five areas of mobility, self-care, everyday activity, pain or discomfort, and anxiety and depression. The EQ-5D tool includes a Visual Analog Scale; patients draw a line directly on the scale and the corresponding score represents their daily health status, scored from 0 to 100 with lower scores indicating worse health status [22]. For the test–retest reliability of items in the EQ-5D, their Kappa coefficients ranged from 0.49 to 1 (p < .001) [23].

Basic demographic questionnaire

Data on age, time since diagnosis (months), education level, marital status, menopause status, and employment status were collected through a self-reported questionnaire. The participants’ medical records confirmed their staging and treatment of cancer.

Research tools for validation

Climacteric symptoms

The Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS) is a 21-item tool that evaluates the following four domains: mental health (items 1–11), physical health (items 12–18), vasomotor function (items 19 and 20), and loss of interest in sex (item 21) on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (extremely) [24, 25]. A higher score indicated more severe menopausal symptoms. The factor loadings were greater than .35, and the internal consistency was indicated by a Cronbach's alpha of .83–.87 [25].

Fidelity

A 6-week intervention by a qualified mindfulness instructor who has received over 9 years of MBSR system training. During the session, the instructor assessed the transfer of MBSR skills by asking questions and discussing material with participants and supervised them every week by the first author (Y.C) who records the duration of the patient’s practice. We have a standardized procedure. First, we set up a mobile LINE group before the course to regularly remind the class time. Second, we will regularly provide verbal encouragement, support and answer the subjects as much as possible in the group. Third, we use the support of the patient group to care for each other and share experiences. Fourth, if the subjects complete all courses, we will provide coupons and evidence-based nutrition as incentives.

Sample size

This study considered the results of previous studies to estimate the number of samples. The study determined the difference in outcomes between the intervention and usual care groups at a statistical power of 80% and 5% type I error to detect an effect size of 0.5 [26], accounting for a potential dropout rate of approximately 20%. Therefore, the total number of participants had to be at least 40.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was conducted using SPSS for Windows 22.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). The collected questionnaires were coded, and the accuracy of the data was verified repeatedly after being input. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. This study had a small sample, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test determined that the data were not normally distributed. Therefore, the differences in absolute values and the changes in values before and after the intervention between the two groups were tested using nonparametric statistical methods. Within-subject changes in the levels of climacteric symptoms, female sexual function, anxiety, depression, stress, and quality of life at pre- and postintervention were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U Test for continuous variables; a Chi-square test was used for the categorical variables. In all analyses, statistical significance was defined by a two-sided p value less than .05.

To examine the magnitude of difference between-group, the effect sizes which were conventionally calculated for small, medium, and large treatment effects were 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively [27]. The larger effect size indicated that MBSR group benefitted more than the usual care group, and vice versa. The website established by Lenhard and Lenhard (2016) [28] can be utilized to compute effect sizes (https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html).

Results

Patient characteristics

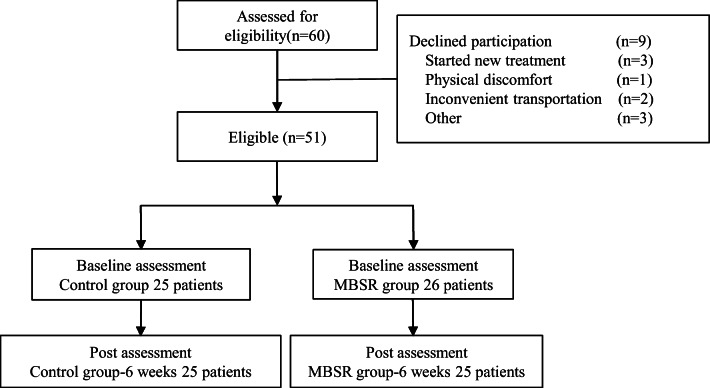

Of the 60 eligible patients (see Fig. 1 Flow diagram of study subjects). As can be seen, the main reasons for declining participation were due to new treatment, physical discomfort, inconvenient transportation, and others. A total of 51 patients were recruited; 26 and 25 people were assigned to the experimental and usual care groups, respectively. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 1. All participants were women and the majority were adults (age: 47.77 ± 9.29 years old). Most had a university education (20, 39.2%), followed by junior college education (12, 23.5%). The majority of participants were married (33, 67.4%), and 10 were single (19.6%). With regard to employment, most were retired (13, 25.5%), nine were working in secondary industry or commerce, and nine were working in occupations classified under other (both 17.6%). A total of 23 (45.1%) patients answered yes for the option regarding menopause, and 28 (54.9%) answered no. The average duration since breast cancer diagnosis was 19.28 ± 15.78 months, and 25 patients (54.9%) were diagnosed as having stage II cancer. At the time of the study, the main form of treatment was hormone therapy (26, 51.0%). No significant difference in the data on basic characteristics of the experimental and usual care group was noted.

Fig. 1.

Flow-chart of study subjects

Table 1.

The demographic and clinical characteristic of patients with breast cancer

| Characteristic | Total (n=51)a |

MBSR (n=26) a |

UC (n=25) a |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age,years (SD) | 47.77(9.29) | 50.19(11.25) | 45.24 (5.90) | .17 |

| Time since diagnosis, months (SD) | 19.28(15.78) | 24.81(19.13) | 13.52(8.37) | .09 |

| Educational, n(%) | .08 | |||

| Elementary | 3(5.9) | 3(11.5) | 0(0.0) | |

| Junior | 2(3.9) | 0(0.0) | 2(8.0) | |

| Senior High | 9(17.6) | 2(7.7) | 7(28.0) | |

| Junior college | 12(23.5) | 6(23.1) | 6(24.0) | |

| University | 20(39.2) | 13(50.0) | 7(28.0) | |

| Graduate institute | 5(9.8) | 2(7.7) | 3(12.0) | |

| Marital status, n(%) | .06 | |||

| Unmarried | 10(19.6) | 8(30.8) | 2(8.0) | |

| Married | 33(64.7) | 15(57.7) | 16(64.0) | |

| Divorced | 5(9.8) | 0 | 5(20.0) | |

| Cohabitation | 2(3.9) | 2(7.7) | 1(4.0) | |

| Separation | 1(2.0) | 1(3.8) | 1(4.0) | |

| Employment status, n(%) | .27 | |||

| Retired | 13(25.5) | 9(34.6) | 4(16.0) | |

| Government employees | 5(9.8) | 1(3.8) | 4(16.0) | |

| Industry/commerce | 9(17.6) | 3(11.5) | 6(24.0) | |

| House Keeper | 8(15.7) | 3(11.5) | 5(20.0) | |

| Service industry | 7(13.7) | 4(15.4) | 3(12.0) | |

| Other | 9(17.6) | 6(23.1) | 3(12.0) | |

| Menopause, n(%) | .07 | |||

| Yes | 23(45.1) | 15(57.7) | 8(32.0) | |

| No | 28(54.9) | 11(42.3) | 17(68.0) | |

| Cancer staging, n(%) | .13 | |||

| Stage Ο | 4(7.8) | 4(15.4) | 1(4.0) | |

| Stage I | 6(11.8) | 5(19.2) | 3(12.0) | |

| Stage II | 25(54.9) | 10(38.5) | 12(48.0) | |

| Stage III | 7(13.7) | 1(3.8) | 6(24.0) | |

| Stage IV | 9(11.8) | 6(23.1) | 3(12.0) | |

| Treatment, n(%) | .43 | |||

| Chemotherapy | 13(25.5) | 9(34.6) | 4(16.0) | |

| Radiotherapy | 4(7.8) | 2(7.7) | 2(8.0) | |

| Targeted therapy | 3(5.9) | 2(7.7) | 1(4.0) | |

| Hormone therapy | 26(51.0) | 10(38.5) | 16(64.0) | |

| Other | 5(9.8) | 3(11.5) | 2(8.0) |

aCategorical variable were presented as frequencies and percentages, continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation. MBSR mindfulness-based stress reduction; UC usual care; SD, standard deviation

Effects of MBSR

The FSFI results indicated significantly improved arousal (Δarousal: 5.73 vs. -5.96, p ≤ .001), lubrication (Δlubrication: 3.35 vs. -3.48, p ≤ .001), orgasm (Δorgasm: 1.6 vs. -1.66, p = .002), satisfaction (Δsatisfaction: 8.48 vs. 1.76, p = .007), and pain (Δpain: 1.92 vs. -1.84, p = .012). With respect to satisfaction, the most effective improvements were noted in the participants’ sexual relationship (postintervention: 26.79 vs. 16.31, p = .005) and overall sexual satisfaction (postintervention: 27.52 vs. 16.82, p = .005). Six consecutive weeks of MBSR sessions improved some aspects of female sexual function in patients with breast cancer. Moreover, effect sizes varied in the postintervention comparative group studies—the medium effect sizes in the arousal and lubrication, the small effect sizes in the orgasm, satisfaction, and pain (Table 2). Patients’ psychological problems were measured by the DASS-21. The scores of the three components of depression, anxiety, and stress did not differ between two groups in preintervention, whereas except for depression, the scores of anxiety and stress were significantly higher in the MBSR group in postintervention (Δanxiety: 17.62 vs. 34.72, p ≤ .001; Δstress: 18.31 vs. 34.00, p ≤ .001) and so did the effects of intervention (Δanxiety: -10.92 vs.11.36, p ≤ .001; Δstress: -10.96 vs.11.40, p ≤ .001). Among the DASS-21 variables, a large effect size was found in lower anxiety and stress. (Table 3). Quality of life was measured with the EQ-5D, and it did not significantly differ between the preintervention and postintervention. Nonetheless, the intervention significantly improved the participants’ conduct of usual activities (Δusual activities: -1.94 vs. 2.02, p = .048). There were small effect sizes, ranging from 0.01 to 0.16, found for MBSR and the usual care group in comparison with EQ-5D variables (Table 4). Typically, 6 weeks of MBSR sessions can only mildly improve the quality of life in patients with breast cancer. The GCS was used to verify the front scales and ascertain whether patients with breast cancer had improvements in their psychological and physical symptoms following 6 consecutive weeks of MBSR. The findings demonstrated that vasomotor function (postintervention: 21.87 vs. 30.30, p = .035), and mental health (Δpsychological: -4.37 vs. 4.54, p = .045) significantly improved at the posttest (Table 5), which was consistent with the results of the FSFI and DASS-21. However, small effect sizes were found for menopause symptoms.

Table 2.

Female sexual function index

| Measure FSFI | Group | Preintervention | Postintervention | Effect of intervention | Postintervention Between-group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rank | p-value | Mean rank | p-value | ΔMean rank | Z | Δp-value | Effect size | ||

| Desire | UC | 28.56 | 0.17 | 24.06 | 0.33 | -4.5 | -1.61 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| MBSR | 23.54 | 27.87 | 4.33 | ||||||

| often of sexual desire | UC | 27.30 | 0.46 | 24.76 | 0.51 | -2.54 | |||

| MBSR | 24.75 | 27.19 | 2.44 | ||||||

| level of sexual desire | UC | 28.76 | 0.13 | 24.26 | 0.37 | -4.5 | |||

| MBSR | 23.35 | 27.67 | 4.32 | ||||||

| Arousal | UC | 30.60 | .027* | 24.64 | 0.51 | -5.96 | -3.91 | .000** | 0.61 |

| MBSR | 21.58 | 27.31 | 5.73 | ||||||

| often of sexually aroused | UC | 30.64 | .022* | 23.54 | 0.22 | -7.1 | |||

| MBSR | 21.54 | 28.37 | 6.83 | ||||||

| level of sexual arousal | UC | 30.70 | .022* | 24.96 | 0.61 | -5.74 | |||

| MBSR | 21.48 | 27.00 | 5.52 | ||||||

| confident of sexual activity | UC | 29.16 | 0.12 | 25.68 | 0.87 | -3.48 | |||

| MBSR | 22.96 | 26.31 | 3.35 | ||||||

| often satisfied with arousal | UC | 29.60 | 0.05 | 26.52 | 0.79 | -3.08 | |||

| MBSR | 22.54 | 25.50 | 2.96 | ||||||

| Lubrication | UC | 29.22 | 0.09 | 25.74 | 0.90 | -3.48 | -4.05 | .000** | 0.67 |

| MBSR | 22.90 | 26.25 | 3.35 | ||||||

| often of lubricated | UC | 29.30 | 0.08 | 26.06 | 0.98 | -3.24 | |||

| MBSR | 22.83 | 25.94 | 3.11 | ||||||

| difficult of lubricated | UC | 29.66 | .049* | 25.80 | 0.92 | -3.86 | |||

| MBSR | 22.48 | 26.19 | 3.71 | ||||||

| maintain of lubricated | UC | 28.92 | 0.12 | 27.14 | 0.56 | -1.78 | |||

| MBSR | 23.19 | 24.90 | 1.71 | ||||||

| difficult of lubricated | UC | 29.04 | 0.10 | 26.32 | 0.87 | -2.72 | |||

| MBSR | 23.08 | 25.69 | 2.61 | ||||||

| Orgasm | UC | 28.72 | 0.15 | 27.06 | 0.59 | -1.66 | -3.10 | .002* | 0.38 |

| MBSR | 23.38 | 24.98 | 1.6 | ||||||

| often of orgasm | UC | 28.60 | 0.16 | 27.06 | 0.59 | -1.54 | |||

| MBSR | 23.50 | 24.98 | 1.48 | ||||||

| difficult of orgasm | UC | 28.80 | 0.13 | 27.18 | 0.54 | -1.62 | |||

| MBSR | 23.31 | 24.87 | 1.56 | ||||||

| satisfied of orgasm | UC | 29.14 | 0.09 | 27.70 | 0.37 | -1.44 | |||

| MBSR | 22.98 | 24.37 | 1.39 | ||||||

| Satisfaction | UC | 19.66 | 0.15 | 21.42 | 0.64 | 1.76 | -2.70 | .007* | 0.29 |

| MBSR | 14.77 | 23.25 | 8.48 | ||||||

| emotional closeness | UC | 29.12 | 0.09 | 27.96 | 0.30 | -1.16 | |||

| MBSR | 23.00 | 24.12 | 1.12 | ||||||

| Sexual relationship | UC | 19.45 | 0.17 | 16.31 | .005* | -3.14 | |||

| MBSR | 15.03 | 26.79 | 11.76 | ||||||

| overall sexual | UC | 20.43 | 0.20 | 16.82 | .005* | -3.61 | |||

| MBSR | 16.09 | 27.52 | 11.43 | ||||||

| Pain | UC | 28.30 | 0.13 | 26.46 | 0.63 | -1.84 | -2.52 | .012* | 0.25 |

| MBSR | 22.70 | 24.62 | 1.92 | ||||||

| during vaginal penetration | UC | 28.54 | 0.10 | 26.13 | 0.75 | -2.41 | |||

| MBSR | 22.46 | 24.92 | 2.46 | ||||||

| following vaginal penetration | UC | 27.80 | 0.21 | 26.44 | 0.64 | -1.36 | |||

| MBSR | 23.20 | 24.63 | 1.43 | ||||||

| level of pain during or following | UC | 28.86 | 0.06 | 26.85 | 0.50 | -2.01 | |||

| MBSR | 22.14 | 24.25 | 2.11 | ||||||

* p≦ .05; ** p≦ .001; Δpost-test minus pre-test scores; FSFI Female Sexual Function Index; MBSR mindfulness-based stress reduction; UC usual care

Table 3.

Mental health of patients

| Measure DASS-21 | Group | Preintervention | Postintervention | Effect intervention | Postintervention Between-group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rank | p-value | Mean rank | p-value | ΔMean rank | Z | Δp-value | Effect size | ||

| Depression | UC | 23.70 | 0.28 | 26.12 | 0.96 | 2.42 | -1.81 | .07 | 0.13 |

| MBSR | 28.21 | 25.88 | -2.33 | ||||||

| Anxiety | UC | 23.36 | 0.21 | 34.72 | .000** | 11.36 | -4.67 | .000** | 0.87 |

| MBSR | 28.54 | 17.62 | -10.92 | ||||||

| Stress | UC | 22.60 | 0.11 | 34.00 | .000** | 11.40 | -4.32 | .000** | 0.75 |

| MBSR | 29.27 | 18.31 | -10.96 | ||||||

*p≦ .05; **p≦ .001; Δpost-test minus pre-test scores; DASS-21 Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21; MBSR mindfulness-based stress reduction; UC usual care

Table 4.

Quality of life

| Measure EQ-5D | Group | Preintervention | Postintervention | Effect of intervention | Postintervention Between-group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rank | p-value | Mean rank | p-value | ΔMean rank | Z | Δp-value | Effect size | ||

| Mobility | UC | 26.02 | 0.98 | 26.54 | 0.53 | 0.52 | -0.58 | 0.56 | 0.01 |

| MBSR | 25.98 | 25.48 | -0.5 | ||||||

| Self-care | UC | 24.50 | 0.08 | 26.02 | 0.98 | 1.52 | -1.71 | 0.09 | 0.12 |

| MBSR | 27.44 | 25.98 | -1.46 | ||||||

| Usual activities | UC | 24.52 | 0.18 | 26.54 | 0.53 | 2.02 | -1.98 | .048* | 0.16 |

| MBSR | 27.42 | 25.48 | -1.94 | ||||||

| Pain/Discomfort | UC | 25.96 | 0.98 | 24.88 | 0.53 | -1.08 | -0.84 | 0.40 | 0.03 |

| MBSR | 26.04 | 27.08 | 1.04 | ||||||

| Anxiety /Depression | UC | 24.84 | 0.51 | 27.20 | 0.50 | 2.36 | -1.25 | 0.21 | 0.06 |

| MBSR | 27.12 | 24.85 | -2.27 | ||||||

| Health state | UC | 27.34 | 0.52 | 25.00 | 0.64 | -2.34 | -0.61 | 0.54 | 0.02 |

| MBSR | 24.71 | 26.96 | 2.25 | ||||||

* p≦ .05; Δpost-test minus pre-test scores; EQ-5D EuroQol instrument; MBSR mindfulness-based; stress reduction; UC usual care

Table 5.

Validations tool of GCS

| Measure GCS | Group | Preintervention | Postintervention | Effect of intervention | Postintervention Between-group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rank | p-value | Mean rank | p-value | ΔMean rank | Z | Δp-value | Effect size | ||

| Psychological | UC | 22.50 | 0.10 | 27.04 | 0.62 | 4.54 | -2.01 | .045* | 0.16 |

| MBSR | 29.37 | 25.00 | -4.37 | ||||||

| Physical | UC | 22.34 | 0.08 | 26.34 | 0.87 | 4.00 | -1.44 | 0.15 | 0.08 |

| MBSR | 29.52 | 25.67 | -3.85 | ||||||

| Vasomotor | UC | 27.94 | 0.33 | 30.30 | .035* | 2.36 | -1.06 | 0.29 | 0.05 |

| MBSR | 24.13 | 21.87 | -2.26 | ||||||

| Loss of interest in sex | UC | 25.54 | 0.82 | 28.44 | 0.22 | 2.90 | -1.87 | 0.06 | 0.14 |

| MBSR | 26.44 | 23.65 | -2.79 | ||||||

* p≦ .05; Δpost-test minus pre-test scores; GCS The Greene climacteric scale; MBSRMindfulness-Based Stress Reduction; UC Usual care

Discussion

This study demonstrated the impact of MBSR in improving female sexual function, anxiety, stress, everyday activity, and vasomotor function among women with breast cancer. However, MBSR yielded no improvement with respect to depression.

Approximately 50–75% of women diagnosed with breast cancer experience sexual difficulties; of those treated with aromatase inhibitors, as many as 79% develop new sexual problems, and nearly 25% stop sexual activity [29–31]. In addition, patients with breast cancer can experience a deteriorating quality of life because of side effects or psychological problems after treatment. Therefore, we hypothesized an immediate increase in the level of female sexual function from pre- to post-MBSR intervention. Our finding indicated that MBSR intervention improves female sexual function, especially in their relationship with their partner and in their overall sexual satisfaction. Previous research analyzed data from three databases (EBSCO, PubMed, and ResearchGate) and the findings of 15 original research articles; the results demonstrated that MBSR can be effectively used to treat female sexual dysfunction, especially with regard to sexual arousal and satisfaction, and to reduce sexual dysfunction related to anxiety and negative cognitive patterns [32]. Studies have determined that MBSR can improve anxiety and stress, self-esteem, sexual relationships, and sexual satisfaction in women [33], which is consistent with the present study’s findings.

No significant improvement in depression with MBSR was noted. Possible reasons may attribute to small sample sizes in each group, length of intervention, and follow-up time.

As a previous study conducted by Würtzen with 336 women (stages I–III) who had undergone breast cancer surgery, randomly assigning them to a routine care or mindfulness intervention group and using intention-to-treat analysis. Patients participated in 6 consecutive weeks of mindfulness intervention; depression did not significantly improve during the posttest (p = .07) but did at the 6 months (p = .01) and 12 months (p = .03) of follow-up [34]. Following MBSR intervention, improvement was noted only in everyday activity and not in the other four items of the EQ-5D. Kanter et al. (2016) determined no difference in the quality of life between an MBSR group and a control group [35], which may be attributable to the short follow-up period of the study or the small sample size. The EQ-5D questionnaire must be administered to patients with serious diseases and who face restrictions in their activity to ensure more meaningful results.

The number of weeks of MBSR execution may result in different outcomes. Traditional MBSR courses last for 8 weeks and can effectively improve quality of life [36–38] and anxiety [34]. However, some studies have indicated that 6 weeks of intervention can also improve quality of life and reduce depression [13]. Demarzo et al. (2017) compared an 8-week mindfulness-based intervention with its 4-week counterpart. The intervention was demonstrated to be effective relative to the control, and the effect sizes of the 4- and 8-week courses were similar findings [39]. Braden et al. (2016) analyzed the effectiveness of a 4-weeks MBSR intervention (n = 12) against a control that involved only reading as a means to reduce stress (n = 11). Studies have shown that 4-week MBSR treatment can alleviate symptoms of low back pain and improve emotional awareness in the frontal lobe and that its 8-week counterpart can yield improvements in depression, anxiety, and cognition. Therefore, improvements in perceived pain are achievable with short-term MBSR intervention, but depression and anxiety may require long-term MBSR [40].

Our study limited the intervention to 6 weeks to better ensure that the study did not cause inconvenience to the participants and to thus encourage their continued participation. Nonetheless, 6 weeks may have been overly short for the intervention to yield improvements in all aspects.

To conclude, future studies should investigate the effects of course duration or adopt an intervention with a longer duration and the recommendation should be that a large sample is needed to reinforce results.

MBSR can improve the mental health of patients with breast cancer, as indicated by the GCS. Climacteric syndrome in patients with breast cancer is usually caused by chemotherapy and hormone therapy [41]. Up to 85% of women with climacteric syndrome have vasomotor symptoms (i.e., hot flashes and night sweats), 60% report vaginal discomfort (i.e., vaginal dryness and dyspareunia), and 86.5% report sexual dysfunction (such as a lack of libido and difficulty in reaching orgasm) [42, 43]. Among the patients in this study, 13 (21.7%) received chemotherapy and 26 received hormonal therapy (43.3%). An improvement in overall climacteric symptoms in the vasomotor domain was noted following MBSR intervention. This finding is consistent with those of a study involving a randomized trial of 110 postmenopausal and early postmenopausal women who experienced an average of ≥5 moderate or severe hot flashes (including night sweats) per day. Additionally, in the vasomotor domain of the GCS scale, the total scores were lower for the MBSR group than the routine care group; this may be because the postmenopausal stage and transition to menopause can induce vasomotor symptoms in younger women [44].

These quantitative results were consistent with the findings of our qualitative interviews. For example, one patient who participated in this course narrated their experience as follows: “I have symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, and frequent urination after taking hormonal drugs. I also feel particularly tired the next day. After doing an MBSR session, I felt an unprecedented peace of mind. When I do mindful breathing and body scanning, I can fall asleep quickly, and I can even sleep until dawn.” As indicated in the statistical analysis and the qualitative responses in the questionnaires, patients with breast cancer were prone to having trouble sleeping and experiencing pain after receiving treatment; sleep and pain can thus be measured independently in future studies. Data from both subjective (e.g., self-reports) and objective (e.g., wearable devices, functional magnetic resonance imaging) sources can be used to establish more specific patterns of how patients sleep and experience pain.

In general, MBSR alleviated the serious problems this study’s participants faced with their physical and mental health. Thus, MBSR can be incorporated into alternative therapies.

Studies have rarely discussed the improvement of female sexual function in breast cancer patients through MBSR intervention and have predominantly considered sexual function to be an unimportant aspect of an individual’s quality of life. The main strengths of our study were that female sexual function was regarded as a vital part of the quality of life, and that MBSR intervention was demonstrated to improve sexual function and mental health. MBSR is a nonpharmacologic therapy, and it is safe, accessible, and simple to practice for patients with breast cancer. In the future, MBSR intervention can be applied in clinical care and established as part of standard care procedures. However, some limitations of our study must also be acknowledged. First, participants in this study were enrolled in women with breast cancer in a group format. The generalizability of findings to other cancer types and their effect on the individual is unknown. Second, we failed to control for confounding variables of our findings in quasi-experimental. Third, the small sample size with inadequate power was unable to detect clinically meaningful effects.

Future research should use random assignment for more robust findings, recruiting different types of cancer, and include a large sample. Mindfulness can be implemented anytime and anywhere and becomes more beneficial with practice; therefore, research tools can incorporate a mobile app to build courses, record information, and provide mindfulness videos to encourage participants to keep up their mindfulness practice. This study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and patients wore protective facemasks during every session. Should other public health crises occur in the future, research interventions can employ distance learning methods. Because of the ease and convenience of course participation, a larger sample can be used in future studies to ensure greater representativeness.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contribution

Y. C. Chang was responsible for the study conception, design, and writing of the manuscript; G. M. Lin was responsible for results analysis, writing and revision of the manuscript; T .L. Yeh was responsible for results analysis and revision of the manuscript; Y. M. Chang was responsible for study conception and revision of the manuscript; C.H. Yang was responsible for the editing and revision of the manuscript; C. Lo was responsible for the revision and analysis of the manuscript; C. Y. Yeh was responsible for the revision of the manuscript; W. Y. Hu was responsible for contributing to the study conception, design, and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All appropriate procedures conducted in research involving human participants were in line with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee in Taiwan.

Consent to participate

All participants signed an informed consent form before participating in the study.

Consent for publication

The manuscript has been seen and approved by all authors, and the material was not previously published.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health and Welfare Taiwan, 2018 Cancer Registry Annual Report (2021) https://www.hpa.gov.tw/Pages/List.aspx?nodeid=119. Accessed 3 Apr 2021

- 2.Streicher L, Simon JA. Sexual Function Post-Breast Cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2018;173:167–189. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-70197-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang YC, Chang SR, Chiu SC. Sexual Problems of Patients With Breast Cancer After Treatment: A Systematic Review. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42(5):418–425. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, et al. Changes in sexual life experienced by women in Taiwan after receiving treatment for breast cancer. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2019;14(1):1654343. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2019.1654343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price-Blackshear MA, et al. Online couples mindfulness-based intervention for young breast cancer survivors and their partners: A randomized-control trial. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2020;38(5):592–611. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2020.1778150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bober SL, Fine E, Recklitis CJ. Sexual health and rehabilitation after ovarian suppression treatment (SHARE-OS): a clinical intervention for young breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(1):26–30. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-00800-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arora N, Brotto LA. How Does Paying Attention Improve Sexual Functioning in Women? A Review of Mechanisms. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5(3):266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brotto LA, et al. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Methods to Evaluate an Online Psychoeducational Program for Sexual Difficulties in Colorectal and Gynecologic Cancer Survivors. J Sex Marital Ther. 2017;43(7):645–662. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2016.1230805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagherzadeh R, et al. Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Training on Revealing Sexual Function in Iranian Women with Breast Cancer. Sex Disabil. 2020;39:67–83. doi: 10.1007/s11195-020-09660-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang Y-C, et al. Short-term Effects of Randomized Mindfulness-Based Intervention in Female Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2020;44:E703–E714. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lengacher CA, et al. Feasibility of the mobile mindfulness-based stress reduction for breast cancer (mMBSR(BC)) program for symptom improvement among breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2018;27(2):524–531. doi: 10.1002/pon.4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bisseling EM, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for breast cancer patients: a mixed method study on what patients experience as a suitable stage to participate. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(10):3067–3074. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3714-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reich RR, et al. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in Post-treatment Breast Cancer Patients: Immediate and Sustained Effects Across Multiple Symptom Clusters. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor AE et al (1999) Observer error in grading performance status in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 7(5):332–335 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Carlson LE, et al. Mindfulness-based cancer recovery and supportive-expressive therapy maintain telomere length relative to controls in distressed breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015;121(3):476–484. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wieland LS, et al. Yoga for treating urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2(2):CD012668–CD012668. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012668.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: The program of the stress reduction clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. New York: Delta; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4(1):33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei SJ, Cooke M, Moyle W, Creedy D (2008) Family Caregivers’ Needs When Caring for Adolescent with a Mental Illness in Taiwan. PhD thesis, Griffith University.

- 22.Pickard AS, et al. Health Utilities Using the EQ-5D in Studies of Cancer. PharmacoEconomics. 2007;25(5):365–384. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang T-J, et al. Taiwanese version of the EQ-5D: validation in a representative sample of the Taiwanese population. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106(12):1023–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greene JG. A factor analytic study of climacteric symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 1976;20(5):425–430. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(76)90005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene JG. Constructing a standard climacteric scale. Maturitas. 1998;29(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5122(98)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matchim Y, Armer JM, Stewart BR. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on health among breast cancer survivors. West J Nurs Res. 2011;33(8):996–1016. doi: 10.1177/0193945910385363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenhard W, Lenhard A (2016) Calculation of Effect Sizes. Psychometrica, Dettelbach (Germany) Retrieved from: https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html. Accessed 11 Sept 2021

- 29.Reese JB, et al. Adapting a couple-based intimacy enhancement intervention to breast cancer: A developmental study. Health Psychol. 2016;35(10):1085–1096. doi: 10.1037/hea0000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reese JB, et al. Effective patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in breast cancer: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(10):3199–3207. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3729-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schover LR, et al. Sexual problems during the first 2 years of adjuvant treatment with aromatase inhibitors. J Sex Med. 2014;11(12):3102–3111. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaderek I, Lew-Starowicz M. A Systematic Review on Mindfulness Meditation-Based Interventions for Sexual Dysfunctions. J Sex Med. 2019;16(10):1581–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leavitt CE, Lefkowitz ES, Waterman EA. The role of sexual mindfulness in sexual wellbeing, Relational wellbeing, and self-esteem. J Sex Marital Ther. 2019;45(6):497–509. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2019.1572680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wurtzen H, et al. Mindfulness significantly reduces self-reported levels of anxiety and depression: results of a randomised controlled trial among 336 Danish women treated for stage I-III breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(6):1365–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanter G, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a novel treatment for interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(11):1705–1711. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3022-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson VP, et al. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on psychosocial outcomes and quality of life in early-stage breast cancer patients: a randomized trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(1):99–109. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1738-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henderson VP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction for women with early-stage breast cancer receiving radiotherapy. Integr Cancer Ther. 2013;12(5):404–413. doi: 10.1177/1534735412473640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahmani S, Talepasand S, Ghanbary-Motlagh A. Comparison of effectiveness of the metacognition treatment and the mindfulness-based stress reduction treatment on global and specific life quality of women with breast cancer. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2014;7(4):184–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Demarzo M, et al. Efficacy of 8- and 4-Session Mindfulness-Based Interventions in a Non-clinical Population: A Controlled Study. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1343–1343. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braden BB, et al. Brain and behavior changes associated with an abbreviated 4-week mindfulness-based stress reduction course in back pain patients. Brain Behav. 2016;6(3):e00443. doi: 10.1002/brb3.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park H, Yoon HG. Menopausal symptoms, sexual function, depression, and quality of life in Korean patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(9):2499–2507. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1815-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ambler DR, Bieber EJ, Diamond MP. Sexual function in elderly women: a review of current literature. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;5(1):16–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santoro N, Epperson CN, Mathews SB. Menopausal Symptoms and Their Management. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2015;44(3):497–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stuenkel CA. Managing menopausal vasomotor symptoms in older women. Maturitas. 2021;143:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.