Abstract

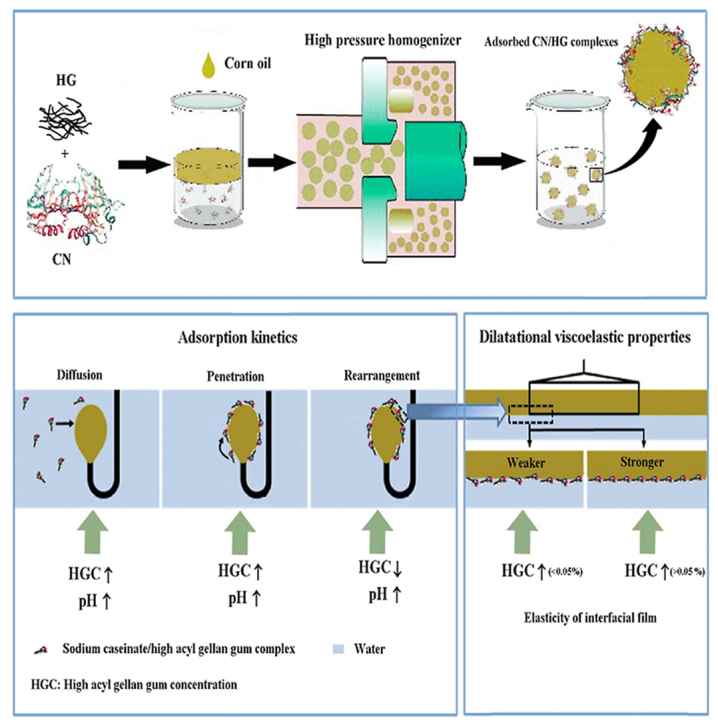

In this work, the effects of pH and high acyl gellan gum concentration on the adsorption kinetics and interfacial dilatational rheology of sodium caseinate/high acyl gellan gum (CN/HG) complexes were investigated using a pendant drop tensiometer. In addition, stability related properties including interfacial protein concentration, droplet charge, size, microstructure and creaming index of emulsions were studied at different HG concentration (0–0.2 wt%) and pH values (4, 5.5 and 7). The results showed that HG adsorbed onto the CN mainly through electrostatic interactions which could lead to increase the interfacial pressure (π), rates of protein diffusion (kdiff), and molecular penetration (kp). The CN/HG complexes formed thick adsorption layers around the oil droplets which significantly increased the surface dilatational modulus with the increasing HG concentration. The CN/HG complexes appeared to form more elastic interfacial films after a long-term adsorption time compared with CN alone, which could reduce the droplet coalescence and thus prevented the growth of emulsion droplets. All four phosphorylated proteins of CN (αs1-, αs2-, β-, and κ-casein) were adsorbed at the oil-water (O/W) interface as confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and surface protein coverage increased progressively with increasing HG concentration at pH 5.5, but decreased at pH 7. The CN/HG stabilized emulsions at pH 5.5 revealed the higher net charges and smaller z-average diameters than those at pH 4 and pH 7. This study provides valuable information on the use of CN/HG complexes to improve the stability and texture of food emulsions.

Keywords: Interfacial dilatational rheology, Adsorb film, Electrostatic interactions, Diffusion, Penetration, Viscoelastic film

Graphical abstract

Highlights

•Interactions between sodium caseinate (CN) and high acyl gellan gum (HG) studied.

•At pH 5.5, CN/HG interaction was mainly driven by electrostatic attractions.

•CN/HG complex improved the adsorption of CN at the oil-water interface.

•CN/HG complex could form stronger interfacial films than protein alone.

•Cooperative adsorption onto oil-water interface improved emulsion stability.

1. Introduction

Proteins and polysaccharides are important functional ingredients in food industry, which can be utilized together with the purpose of stabilization of food emulsions. The proteins are considered as surface-active molecules, usually dominate primary adsorption onto oil droplets, and incorporation of polysaccharides may improve the structure and stability of emulsions through their thickening and gelling behavior as well as steric and electrostatic effects (Dickinson, 2008; Doublier et al., 2000). Food gums may be used as stabilizers or emulsifiers which can adsorb to the protein coated droplets through electrostatic interactions, and influence the rheological properties and stability with respect to aggregation and flocculation (Dickinson, 2003; Li et al., 2016). When protein-polysaccharide mixtures introduced into emulsions simultaneously, the rates of protein diffusion, penetration, and rearrangement may be influenced at different extents due to the electrostatic interactions between the biopolymers (Dickinson, 2003; Li et al., 2016). It has been reported that an electrostatically induced co-adsorption of protein with anionic polysaccharides can influence the interfacial tension and dilatational rheological properties (Dickinson, 2008). The addition of a negatively charged polysaccharide may lead to positive or negative effects on the protein-stabilized emulsions, and extent of protein-polysaccharide interactions depends on many factors such as biopolymers characteristics (i.e., biopolymer-type, size, conformation and mixing ratio), total biopolymers concentration, and solvent conditions (i.e., temperature and pH etc.) (Lam and Nickerson, 2013).

Sodium caseinate (CN) is extensively utilized in food emulsions due to its exceptional nutritional and functional characteristics in combination with other hydrocolloids. CN contains four phosphorylated proteins (αs1-, αs2-, β- and κ-caseins), which compose of hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions, and adsorb to the oil droplet surface, providing stability to emulsions through a combination of electrostatic and steric interactions (Dickinson, 1999; Liang et al., 2014). Many studies have reported that when the concentration of CN is about 2 wt% or more, the emulsions showed rapid creaming which was ascribed to the depletion flocculation of oil droplets (Euston and Hirst, 1999; Hemar et al., 2001; Srinivasan et al., 2000). Moreover, CN stabilized emulsions are sensitive to acidic conditions which triggered flocculation even sometimes destabilization (Jenkins and Snowden, 1996). However, addition of polysaccharides (e.g., xanthan gum, carboxymethylcellulose and carrageenan etc.) as stabilizing agents to CN stabilized emulsions stimulated the formation of thick interfacial layer around the oil droplets which could inhibit the aggregation and flocculation (Surh et al., 2006; Farooq et al., 2021).

Gellan gum is a negatively charged, linear exopolysaccharide which is secreted by the bacterium Sphingomonas elodea, and compose of tetrasaccharide (1,4-β-d-glucuronic acid, 1, 3-β-d-glucose, 1,4-α-l-rhamnose, 1,4-β-d-glucose) repeating units. Gellan gums are classified into high acylated (HG) (i.e., native form), and deacylated forms according to the acyl substituents (Moritaka et al., 1995; Rodrí;guez-Hernández et al., 2003). Vilela and Cunha (2016) reported that the addition of HG formed stable emulsions, and elastic properties of emulsions were mainly depended on the electrostatic repulsion. In addition, HG content in the aqueous phase exhibited high viscosity and gel-like behavior. HG has ionized carboxyl groups just like other polysaccharides (i.e., pectin, carrageenan and xanthan gum etc.) which may influence the stability of CN coated emulsion droplets (Vilela and Cunha, 2017). The interactions of HG with proteins have been extensively reported in literature as they are affected by ionic strength, temperature, and pH ( HYGoh et al., 2006; Guo et al., 2014; Sosa-Herrera et al., 2008; Vilela and Cunha, 2017; Wassén et al., 2013; Zia et al., 2018). However, the effects of HG on the interfacial dynamic properties of adsorbed layers of CN at the O/W interface of emulsions have not been reported yet, which may significantly help understand the adsorption behavior of CN at the O/W interface.

The aim of this study was to investigate the interactions between HG and CN at pH 2–7 by analyzing the phase diagram, and then study the interfacial properties, adsorption kinetics, dilatational characteristics, and interfacial protein concentration. In addition, droplets size distribution, zeta potential, microstructure and creaming stability of CN/HG stabilized emulsions were characterized.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Sodium caseinate was supplied by Harbin Pinchen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Harbin, China). The composition of CN was 91.2 wt% protein, 1.1 wt% fat, 4.2 wt% moisture, 3.4 wt% ash, and 0.l wt% lactose. High acyl gellan gum (HG) (Kelcogel LT-100) was supplied by Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (Shanghai, China). Corn oil was purchased from local supermarket, and all other chemicals were of analytical grade. Deionized water was used to prepare samples.

2.2. Preparation of CN/HG aqueous solutions

CN solutions were prepared by mixing 1 wt% CN into sodium phosphate buffer (5 mM, pH 7) using magnetic stirring at 25 ± 1 °C for 10 h. HG solutions were prepared by dispersing 0.05–0.2 wt% HG powder into sodium phosphate buffer (5 mM, pH 7) using magnetic stirring at 25 ± 1 °C for 18 h to completely hydrate. The prepared stock solutions of CN and HG were mixed in proper ratios, and then adjusted to pH (2–7). CN/HG mixtures were stirred gently for 2 h to remove air bubbles, and then used for characteristic measurements, and emulsion preparation.

2.3. Preparation of emulsions

Corn oil-in-water emulsions were prepared by dispersing 10 wt% corn oil into 90 wt% aqueous solution containing CN/HG by a high speed blender (IKA TURRAX T25 Wilmington, NC) for 4 min at 25 °C. These emulsions were further processed with a high pressure homogenizer (AH100B, ATS, Canada) for 4 min at 35 MPa. Sodium azide (0.04 wt%) was added to the emulsions as preservative.

2.4. Phase diagram of CN/HG mixtures

The phase diagram of CN/HG mixtures was assessed by mixing constant concentration of CN (1 wt%) with different amount of HG (0–0.2 wt%). After that, pH of mixtures was adjusted from 2 to 7 using 1 mM HCl and 0.2M NaOH. These mixtures were stored for 24 h at 25 ± 1 °C, and then visual appearance was assessed as a precipitate, cloudy/milky solution or a clear solution.

2.5. Rheological measurements

Rheological experiments were carried out on a rotational rheometer (MCR302, Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) equipped with a 50 mm parallel plate (PP50) geometry. The gap between the plates was set to 1.0 mm. The temperature was regulated by a Peltier system fitted with a fluid circulator. The apparent viscosity (η) of the emulsions was determined over a shear rate (γ) range of 1–100 s−1 at 25 °C, and then fitted to Ostwald de Waele model equation:

| η = Kγn−1 | (1) |

2.6. Measurement of interfacial properties

Dynamic surface pressure (π) of CN and CN/HG mixtures was determined following the method of Liu et al. (2016) with slight modification. An optical contact angle meter (OCA 20, Data physics Instrument GmBH, Germany) was used to determine the π and dilatational properties of CN or CN/HG mixtures adsorbed at the O/W interface. The CN or CN/HG mixtures were delivered to a syringe and then a droplet was placed to the optical glass cuvette having purified oil, allowing the drop to stand for 10,000 s at the top of the needle to attain protein adsorption. Charged Coupled Device (CCD) camera was used to take images of the drop, and surface pressure is calculated by; π = γ0 − γ, where γ and γ0 are interfacial tension of CN or CN/HG mixtures, and phosphate buffer, respectively. All the experiments were carried out at pH 5.5 and 25 °C. The CN/HG mixtures were diluted with phosphate buffer at a ratio of 1:10 and at pH 5.5 before analysis.

Dilatational viscoelastic modulus of CN/HG mixtures at O/W interface were determined as a function of adsorption time (θ) at 0.1 Hz angular frequency (ω) and 10% deformation amplitude (ΔA/A). The method involved a periodic automated-controlled, sinusoidal interfacial expansion and compression were conducted by increasing or reducing volume of droplet at desired angular frequency and amplitude. The surface dilatational modulus (E) was calculated by following equation (Lucassen-Reynders et al., 1975):

| E = dϭ/(dA/A) = −dπ/dlnA = Ed + ὶEv | (2) |

where ϭ is the interfacial tension.

E is composed of two parts i.e., real and imaginary. The real part (Ed= |E| cosφ) is the dilatational elasticity, and imaginary part (Ev= |E| sinφ) is the dilatational viscosity, where φ is the phase angle between strain and stress to determine relative film viscoelasticity. Sinusoidal oscillations for dilatational properties were performed with 5 oscillation cycles followed by 40 cycles without oscillation to the desired adsorption time. Measurements were performed twice, and reproductively of findings was better than 5% and 1% for E and π, respectively.

2.7. Surface protein concentration and composition

Surface protein composition and concentration of the emulsion samples were determined according to method Zhao et al. (2009) with some modification. The emulsion samples were centrifuged (CR22G centrifuge, Hitachi Co., Japan) at 12000×g for 30 min at 25 °C. The collected cream layers from the top were dried on whatman filter papers, and re-suspended into water to the same volume. Kjeldahl method (N × 6.38) (Elementar Inc., Hanau, Germany) was used to measure protein content of cream layers, and protein concentration was calculated by:

| Surface protein concentration = Protein content × 1000/specific area | (3) |

where specific area was determined using Eq. (5). Protein composition adsorbed at the O/W interface was determined using SDS-PAGE. SDS buffer was prepared with 200 mM Tris-HCl, 20% Glycerol, 4% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 1% SDS at pH 6.8. The cream solution (400 μL) mixed with SDS buffer (650 μL) were heated at 95 °C for 5 min, and centrifuged (CR22G centrifuge, Hitachi Co., Japan) at 12000 g for 12 min. Aliquots (10 μl) were loaded into stacking gel (4.5%) and resolving gel (15%) in Bio-Rad electrophoresis (Bio-Rad, California, USA). Gels were then fixed with 0.30% Coomassie Blue R250, and stained in 40% trichloroacetic acid, and then destained with a water-methanol solution (7% acetic acid, v/v and 40% methanol, v/v). Gels were photographed with a digital camera (Gel Doc, Hercules, USA).

2.8. ζ-potential and droplet size measurements

All the emulsions were diluted 100 times with phosphate buffer (5 mM) at the same pH of samples. ζ-potential was measured using Malvern Mastersizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern instrument Co. Ltd, UK) at 25 °C, and measurements were performed triplicate.

Droplet size distribution was measured by a Mastersizer 2000 (Malvern instrument Co. LTD, UK). Each emulsion (1 mL) was diluted one thousand time with distilled water, and refractive index of continuous phase and disperse phase were fixed as 1.33 and 1.46, respectively. The mean diameter value (d4,3) was calculated by:

| d4,3= ∑nidi4/ ∑nidἱ3 | (4) |

| (5) |

where ni, d3,2 and ρ are the number of droplets of diameter di, surface mean diameter, and density of emulsion, respectively. The measurements were performed immediately after the emulsions preparation, and results were obtained from average of three readings.

2.9. Microstructure of emulsion

Microstructure of emulsions was observed under a De-convolution microscope (Zeiss Axioplan 2 optical imaging) equipped with a camera, and observations were made at a magnification of 63 × . An aliquot (10 μL) was placed on a glass slide and then covered with a coverslip to ensure that no air bubbles were left. The Axiovision 2.0 software was used to take images (1024 × 1024 pixels).

2.10. Creaming stability

Prepared emulsions were transferred into a glass test tube which was then sealed with a plastic cap, and stored for 21 days at 25 ± 1 °C. During this period, emulsion samples were separated into three layers i.e., serum at the bottom, a transparent, and cream layers at the top. These layers were distinguished by visual appearance. The creaming index (CI) of emulsions was calculated by following Equation:

| CI% = (HC/HE) × 100 | (6) |

where HC and HE are the height of the cream layer, and total height of the emulsion, respectively.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Each of experiment was carried out in triplicate using freshly prepared emulsions, otherwise unless stated. The mean ± standard deviations were calculated from replicate measurements and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a subsequent Tukey's test (p < 0.05) using SigmaPlot 12.0.

3. Results and discussion

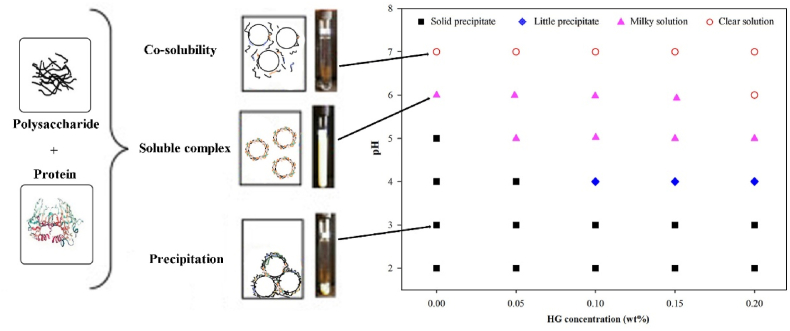

3.1. Phase diagram

Phase behavior of CN/HG mixtures containing different concentration of HG (0–0.2 wt%) at various pH (2–7) conditions is shown in Fig. 1. Four different states of mixtures were found during storage for 24 h at 25 ± 1 °C. It has been observed that CN alone shown a profile distinct from other mixtures by forming a solid precipitate at pH 5 and below, which was ascribed to syneresis of proteins (Kobori et al., 2009). The mixtures of CN/HG formed solid precipitates at pH 2 and 3 which could be ascribed to relatively low negative charged density of HG (0.25 mol negative charge per mole) to protect the CN in comparison with highly charged polysaccharides (e.g., pectin, dextran, and carrageenan) (de Jong and van de Velde, 2007; Zhang et al., 2014). It has been observed that transparent particles were present in the serum layer at pH 4, which ascribed to the formation of precipitates that were denser than water. However, higher the ratio of CN/HG led to a higher degree of intermolecular interactions at pH 5 and above. It is worthy considering that the turbidity of systems reduced slowly with increasing HG concentration at pH > 5, which indicated that soluble complexes were formed resulting from adsorption of HG onto CN molecules. However, the CN/HG mixture modes were dependent on pH and total biopolymers concentration (Liu et al., 2016). Liu et al. (2016) reported a similar finding in which turbidity of CN/carboxymethylcellulose systems was decreased progressively with the increasing concentration of carboxymethylcellulose at pH 5.5, suggesting that soluble complexes were formed resulting in adsorption of carboxymethylcellulose onto CN molecules.

Fig. 1.

Phase diagram of CN/HG mixed systems expressed in term of pH and HG concentration (1 wt% CN, 5 mM PBS buffer). The solubility/insolubility was assessed by visual appearance as a solid precipitate, little precipitate, cloudy/milky solution, and clear solution.

3.2. Effect of CN/HG interactions on rheological behavior

The viscosity of CN emulsions remained 2.5 mPa s over a shearing rate from 40 to 100 s−1 (viscosity below 40 s−1 was too low to be measured). On the basis of the Ostwald-de Waele model, K and n values of CN/HG mixtures containing 1 wt% CN and 0.15 wt% HG at different pH values (2–7) were calculated and shown in Table 1. The CN/HG stabilized emulsions exhibited a pseudo-plastic flow behavior with a shear-thinning phenomenon, and the K values reduced progressively as pH ranging from 7 to 2, while n values increased. Overall, the viscosity of CN/HG stabilized emulsions was affected by the pH values, demonstrating that molecular interactions between the biopolymers took place (Chen et al., 2017). The higher values of viscosity at pH 5–6 as compared with those under acidic conditions were ascribed to the biopolymer interactions and the formation of a soluble CN/HG hybrid (Kobori et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2016). Further lowering of pH values drastically reduced the viscosity due to the formation of protein-polysaccharide complex precipitates. The pseudo-plastic flow behavior and relatively high values of viscosity for protein-polysaccharide complexes have been reported by earlier studies such as CN/xanthan, CN/carboxymethylcellulose, whey protein/carboxymethylcellulose, and whey protein isolate/xanthan systems, which suggested the formation of strong electrostatic attractive interactions between biopolymers (Kobori et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2012, 2016).

Table 1.

Power law fitting parameters for CN/HG mixtures (1 wt% CN plus 0.15 wt% HG) stabilized emulsions at 25 °C.

| pH | K | n | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.013 | 0.685 | 0.982 |

| 3 | 0.042 | 0.641 | 0.991 |

| 4 | 0.209 | 0.521 | 0.985 |

| 5 | 0.430 | 0.495 | 0.984 |

| 6 | 0.318 | 0.512 | 0.992 |

| 7 | 0.276 | 0.584 | 0.991 |

3.3. Interfacial properties

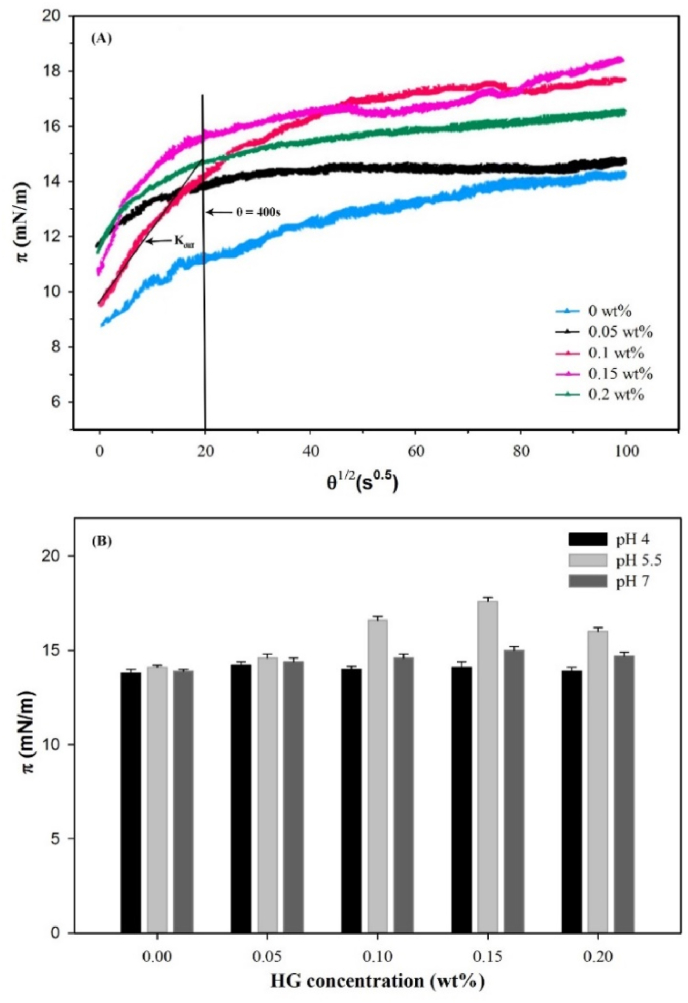

3.3.1. Interfacial pressure

Fig. 2A shows the influence of HG concentration (0–0.2 wt%) on the dynamics of formation of CN films at the O/W interface. In present study, dynamic of interfacial pressure (π) increased with the adsorption time (θ), which was correlated with protein adsorption phenomenon at the O/W interface (Graham and Phillips, 1979). Initially, a very short lag stage was observed indicating minimal conformational changes in proteins, which was also reported by Hunt and Dalgleish (1994), that it is not possible for protein adsorption to reach an equilibrium even after 2 days. The rate of increase in π was decreased with time, which attributed to the surface saturation by proteins and increased electrostatic energy barriers for further adsorption (Graham and Phillips, 1979).

Fig. 2.

(A) The square root time (θ1/2) dependence of dynamic interfacial pressure (π) for CN/HG adsorbed films at the O/W interface at pH 5.5. (B) Effect of pH and HG on dynamic interfacial pressure of CN adsorbed films at the O/W interface after absorption for 10,000 s (1 wt% CN, Temperature = 25 °C). All solutions were diluted 1:10 with 5 mM PBS buffer at the same pH before analysis.

The values of interfacial pressure were increased with adsorption time and HG concentration, which were attributed to the substantial effect of HG on the CN characteristics to adsorb at the O/W interface from the very beginning. The value of interfacial pressure was increased up to a maximum 17.51 mN/m at 0.15 wt% concentration of HG due to improved surface activity of CN/HG mixtures, while further increase in HG concentration caused a decrease in interfacial pressure. It is hypothesized that increased in interfacial pressure might be ascribed to the formation of soluble CN/HG complexes. As HG is a negatively charged high molecular weight polysaccharides, finite thermodynamic incompatibility between HG and CN may exist, which led to segregation phenomenon in bulk solution (Picone and da Cunha, 2010), and resultantly increased the interfacial pressure value (Perez et al., 2009). Since both polymers were negatively charged at pH 5.5 as it was shown by ζ-potential values, therefore, coacervation is, in principle, not possible. However, casein molecules were reported to have slight positively charged regions on the surface (Spagnuolo et al., 2005). The possible complexation between casein particles and HG chains was electrostatic interactions, as reported by Ye et al. (2006) for CN/gum arabic mixtures. As the pH (5.5) of the emulsions was little higher than the IEP of casein, the repulsive interaction between CN and HG was relatively low, and hence the complexation seems to be possible (Ye et al., 2006).

Fig. 2B shows the effect of HG concentration on the π values of CN adsorbed firms after 10,000 s. At pH 4 and 7, the adsorption behavior of CN molecules was not significantly affected by the addition of HG, indicating that CN molecules were favorably adsorbed at the oil-water interface. However, lowering the pH value to 5.5, HG molecules were started adsorbing to the CN coated droplets which caused an increase in the π values of CN adsorbed films. These results suggested that presence of HG concentration in aqueous phase showed significant effects on adsorption behavior of CN at the O/W interface (Chen et al., 2018). Likewise results were reported by Sosa-Herrera et al. (2008) for CN/HG, and Zhao et al. (2009) for CN/xanthan gum solutions, where an increase in interfacial pressure was attributed to the increased concentration of polysaccharides.

3.3.2. Adsorption kinetics

The adsorption of proteins at the O/W interface has been reported most crucial stage in formation and stability of an emulsion. Protein molecules may go through conformational changes during adsorption due to overcome energy barrier or interaction with the surface. The protein adsorption to O/W interface was reported to take place in 3 stages: (i) diffusion from aqueous phase to O/W interface, (ii) penetration to O/W interface, (iii) reorganization/unfolding at the interface (Graham and Phillips, 1979; Zhao et al., 2009).

The kinetics of adsorption at the O/W interface could be monitored depending on the variations in interfacial pressure values. For this purpose, modified equation of Ward and Tordai can be employed to correlate the changes in interfacial pressure (π) with time (Ward and Tordai, 1946):

| π = 2C₀KT(Ddiffθ/3.14)0.5 | (7) |

where K, T, C₀, and Ddiff are the Boltzmann constant, absolute temperature, concentration in bulk phase, and diffusion rate coefficient, respectively. However, if the protein diffusion process at the O/W interface is controlled by adsorption, then a plot of θ1/2 and π would be linear, and slope of this graph presents the diffusion rate (kdiff) (Liu et al., 2011).

The rate constants of dynamic adsorption of CN to the O/W interface as a function of HG concentration are shown in Table 2. The kdiff of CN alone observed to be low at pH value close to the IEP where aggregation of protein hindered the diffusion, leading to poor emulsifying efficiency, while CN/HG mixtures exhibited an increase in kdiff from 0.112 to 0.238 mNm−1s−0.5 by increasing HG concentration from 0.05 to 0.15 wt%. The increase in kdiff values at moderate concentration of HG was ascribed to the existence of finite thermodynamic incompatibility between HG and CN which could lead to segregation phenomenon in bulk solution, thus improved the diffusion rate (Liu et al., 2011). However, kdiff value of CN/HG mixture was decreased to 0.187 mNm−1s−0.5 at 0.2 wt% of HG due to high viscosity which offered high resistance to diffusion and/or steric hindrance. Liu et al (2011) reported that kdiff value of CN decreased in CN/xanthan gum mixed systems with the increasing concentration of xanthan gum compared to CN system.

Table 2.

Characteristic parameters of dynamic interfacial rheology of CN/HG complexes adsorbed at the O/W interface, including the rates of protein diffusion (kdiff), molecular penetration (kp), and conformational rearrangement (kr).

| HG Concentration (wt%) | kdiff (mNm−1s0.5) (LR)a | kp × 104 s−1 (LR)a | kr × 104 s−1 (LR)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.067 ± 0.002 (0.986)a | 2.02 ± 0.010 (0.968)a | 5.26 ± 0.020 (0.966)a |

| 0.05 | 0.112 ± 0.010 (0.998)c | 1.98 ± 0.054 (0.998)c | 5.58 ± 0.018 (0.978)c |

| 0.1 | 0.221 ± 0.085 (0.996)d | 2.35 ± 0.058 (0.996)d | 5.19 ± 0.087 (0.984)d |

| 0.15 | 0.238 ± 0.021 (0.989)e | 2.51 ± 0.080 (0.969)e | 5.04 ± 0.085 (0.997)e |

| 0.2 | 0.187 ± 0.012 (0.981)f | 1.94 ± 0.081 (0.996)f | 4.36 ± 0.003 (0.968)f |

Different letters within the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05, n = 3).

Linear regression coefficient.

After the diffusion of proteins to the O/W interface, rate of adsorption is controlled by the penetration and rearrangements which can be measured by a first-order phenomenological equation (Graham and Phillips, 1979):

| ln(πf– πθ) / (πf– π0) = – kiθ | (8) |

where π0, πf, πθ and ki are corresponded to surface pressure at the initial adsorption time, final time, at any time, and first-order rate constant, respectively. Practically, Eq. (8) often generates two or more linear regions in which first-order rate constant of penetration (kp) and rearrangement (kr) are corresponded to initial and second slope, respectively.

It has been observed that the values of kp increased progressively with the increasing HG concentration (Table 2), suggesting that HG facilitated the penetration of CN towards the interface and unfolding of the adsorbed proteins at the interface. This behavior was ascribed to the molecules adsorption owing to interactions between CN/HG and/or CN aggregation in presence of HG (Perez et al., 2009). Remarkably, the highest value of kp was observed at a HG concentration of 0.15%, which could be associated with the formation of CN/HG complex at pH 5.5 that decreased the molecular entanglement and improved the penetration of proteins, and in addition, it was suggested that the 0.15 wt% HG enhanced the exposure of hydrophobic groups on the CN surface which could stimulate the penetration of protein molecules. A similar finding was reported by Perez's work in which sodium alginate and λ-carrageenan complexes with whey protein concentrate increased the values of kp (Perez et al., 2009). Initially, CN/HG mixed systems exhibited an increase in kr value followed by decreased with the increasing HG concentration which could be attributed to the enhanced adsorption of biopolymers at the oil-water interface that left little space for their rearrangements (Liu et al., 2012). Moreover, the enhanced attractive interactions between CN/HG at the O/W interface would hinder the reorganization of proteins by providing steric repulsion (Ward and Tordai, 1946). These results were quantitatively consistence with the hypothesis that rearrangement rate of adsorbed proteins was reported to be lower for more unfolding of proteins (Graham and Phillips, 1979).

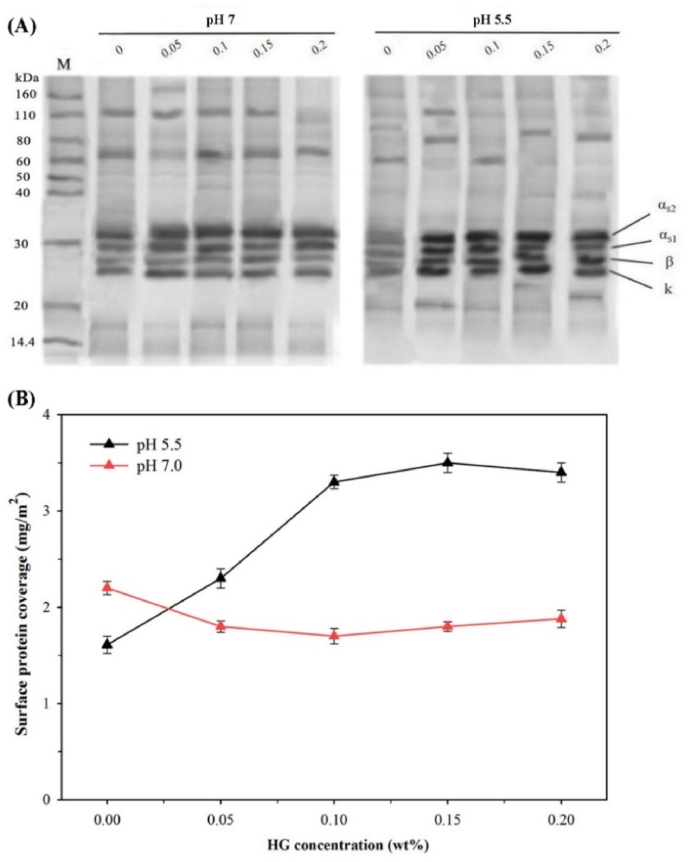

3.4. Dilatational rheological properties

Dilatational viscoelastic properties are used to study the protein-polysaccharides interactions at the O/W interface, and capability of protein to resist displacement. Surface dilatational modulus (E), and elasticity (Ed) of CN adsorbed films at various HG concentration (0–0.2 wt%) are shown in Fig. 3. The curves of π and E as shown in Fig. 3A, indicate the nature of molecules adsorbed at the O/W interface, which is mainly a sensitive tool for evaluating the adsorption behavior of proteins (Liu et al., 2012). The values of E were increased as the π increased, which suggested the existence and development of interactions between protein-polysaccharides and protein-interface. In addition, E values were increased with the longer adsorption time, showing consistency with the model of Lucassen-Reynders for proteins adsorption (Lucassen-Reynders et al., 1975). Overall, CN showed a maximum increased in E value at a HG concentration of 0.15 wt% and then decreased with increasing concentration to 0.2 wt%. This adsorption behavior of CN was quite similar to milk protein (Bos and van Vliet, 2001), and soy globulin (Rodríguez Patino et al, 2003) at the O/W interface.

Fig. 3.

(A) Interfacial pressure (π) dependence of interfacial dilatational modulus (E) for CN/HG complex layers adsorption to the O/W interface. (B) Surface dilatational elasticity of CN as a function of adsorption time for different HG concentration. All solutions were diluted 1:10 with 5 mM PBS buffer at the same pH before analysis. Frequency: 0.1 Hz, amplitude of compression/expansion cycle: 10%.

The slope of E-π curves indicates the adsorption and the degree of interactions between polysaccharide and protein molecules (e.g., electrostatic repulsion, hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds) (Tang and Shen, 2015). The slopes of E-π curves are more than one as indicated by Fig. 3A, which pointed out non-ideal adsorption of CN/HG molecules at the O/W interface. In all the cases, when π value reached to 12 mN/m, the slopes were considerably enhanced, indicating the increased adsorption of proteins at the interface due to the strengthened interactions between biopolymers. Our findings were consistent with the results of whey protein concentrate/polysaccharides (Perez et al., 2009), and soy protein isolate/polysaccharides mixtures at the O/W interface (Wang et al., 2012). Interestingly, slopes of E-π increased to some extent with π values at the very beginning, which indicated the weak interactions between polysaccharides and proteins. Liu et al. (2016) reported that the slight increase in the values of initial slopes with π for CN/carboxymethylcellulose solutions, indicating the weak interactions owing to the protein aggregation, and then significant increment in the values of E observed, which could reveal the presence of more interactions within the adsorbed biopolymer residues as a result of penetration of adsorbed proteins.

Surface dilatational elasticity of CN as a function of HG concentration is shown in Fig. 3B. In all the cases, the gradual increase in surface dilatational elasticity of CN with time is observed which could be ascribed to the adsorption of protein and development of intermolecular interactions at the O/W interface (Liu et al., 2016). At the beginning of adsorption, surface dilatational elasticity values of CN/HG mixed systems were increased quickly, illustrating the elastic behavior of the interfacial layers at the initial stage which could be related to the fast diffusion of CN to the interface (Wang et al., 2012), and then reached to the equilibrium state after approximately 6000 s. The CN/HG mixtures formed stronger viscoelastic films, which are ascribed to their ability to form densely packed layers with in-plane protein-polysaccharides interactions at the O/W interface, suggesting that HG concentration was beneficial to form high viscoelastic interface (Liu et al., 2016).

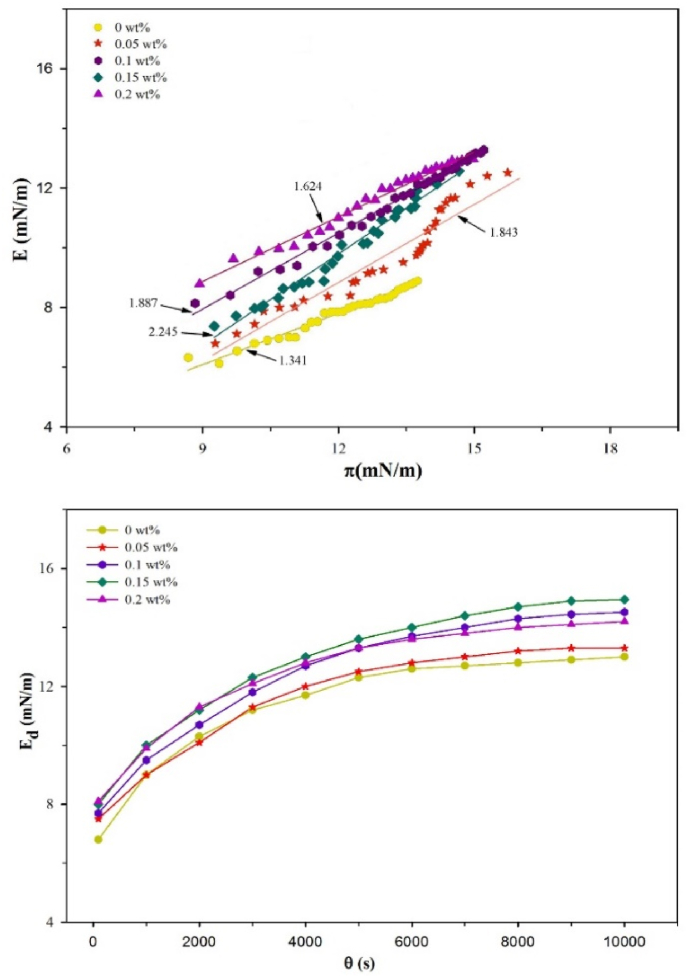

3.5. Interfacial protein composition and concentration

The SDS-PAGE and Kjedahl methods were used to analyze the composition and concentration of surface protein, and results are shown in Fig. 4. The band distribution in the SDS-PAGE indicated the migration ability of proteins depending on the molecular weight. All four phosphorylated proteins of CN (αs1-, αs2-, β-, and κ-casein) were adsorbed at the O/W interface as shown in Fig. 4A, which was consistent with the findings of Hunt and Dalgleish (1994). It has been observed numerous slow moving diffused materials in CN/HG mixtures, which indicated the presence of tiny-sized spurious masses in the CN material (Chu et al., 1995), which cannot be completely removed during preparation. These contaminants were also reported in previous studies of CN/β-glucan mixtures (Agbenorhevi et al., 2013). The individual proteins adsorbed with different amount of level, might be largely ascribed to the various states of protein structure at the surface. At pH 7, SDS-PAGE bands showed that amount of each type of protein adsorbed at droplet surface was slightly enhanced with HG concentration as demonstrated by intensity of proteins bands. However, at pH 5.5, the intensity of proteins bands was gradually increased with the increasing concentration of HG, indicating adsorbed proteins at the droplet surface when HG existed in the continuous phase. Similar findings were reported by Agbenorhevi et al. (2013) for CN/β-glucan mixtures at the O/W interface, where CN adsorption increased with β-glucan concentration.

Fig. 4.

Effect of HG concentration on (A) surface protein composition of CN/HG mixtures stabilized emulsions at pH 5.5 and 7 (M is protein molecular weight marker) and (B) Surface protein coverage (10% corn oil, 1% CN, 5 mM PBS).

The surface coverage of emulsion droplets is shown in Fig. 4B. At pH 5.5, the CN alone showed low protein surface coverage (1.61 mg/m2) which was mainly ascribed to the low adsorption of CN due to aggregation near the IEP. However, surface coverage was increased to 3.51 mg/m2 as the concentration of HG reached up to 0.15 wt%, but further increasing HG caused a slight reduction in protein coverage (3.4 mg/m2). The protein coverage of droplets was high at low HG concentration (i.e., at 0.15 wt% compared to 0.2 wt% HG) could be attributed to the complexation of CN and HG that promoted their interfacial adsorptions in a cooperative manner (Liu et al., 2012). At pH 7, CN showed more protein surface coverage (2.19 mg/m2) and decreased moderately from 2.19 to 1.70 mg/m2 as HG concentration increased from 0 to 0.1 wt%. It might be possible that the interactions between CN and HG decreased as both of biopolymer were negatively charged. But protein surface coverage increased to 1.88 mg/m2 at 0.2 wt% HG, which might be ascribed to the formation of multilayer interfacial films and/or closely packed adsorbed proteins in the monomolecular film, that related to the thermodynamic incompatibility between protein molecules and unadsorbed HG (Hunt and Dalgleish, 1994). The electrostatic repulsion between the arriving molecules and adsorbed film might be reduced, leading to increase the rate of adsorption and subsequently surface protein coverage. Liu et al. (2012) reported that CN adsorption at the droplet surfaces increased as the concentration of carboxymethylcellulose increased at pH of 7, while decreased at pH 4.

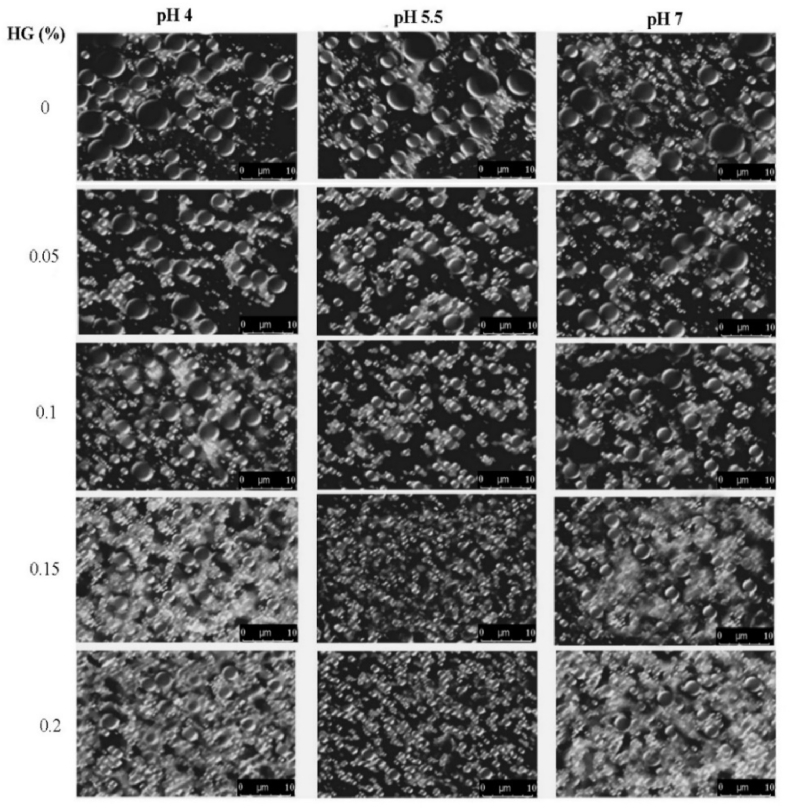

3.6. Emulsion morphology

Microscopic profiles of emulsion droplets as a function of HG concentration and pH are shown in Fig. 5. All the CN stabilized emulsions exhibited aggregation and large oil droplets, which was attributed to the low net charges that decreased the electrostatic repulsions, and led to increase the attractive forces between droplets and stimulated coalescence. It is well-known that the amount of CN (1 wt%) used in this study was adequate to cover all of droplet interface formed during emulsification. Therefore, the presence of small population of large droplets in the emulsions might be associated with the droplet coalescence during or after homogenization, or owing to lack of viscous continuous phase and CN/HG interactions. At a lower HG concentration, some empty spaces have been observed between the droplets, which were due to insufficient concentration of polysaccharides. At pH 5.5, emulsions showed low flocculation after 0.05 wt% HG concentration, which was due to more viscous network formed by the co-gelation of HG that limited the aggregation of droplets (Bos and van Vliet, 2001; Liu et al., 2012). It has also been attributed to the electrostatic and steric interactions between oil droplets which inhibited them from coming closer.

Fig. 5.

Effect of HG concentration and pH on the microstructure of CN/HG stabilized emulsions. The emulsions were visualized within 8 h of preparation.

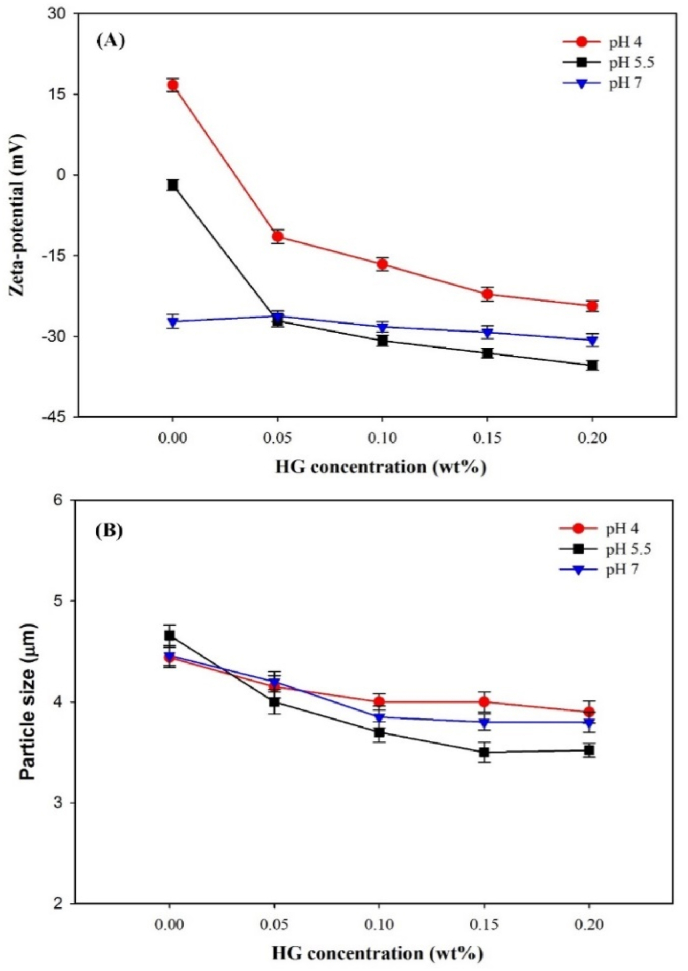

3.7. ζ-potential and particle size analyses

Fig. 6 shows the ζ-potential and particle size of CN/HG stabilized emulsions at various pH values (4, 5.5 and 7) and HG concentration. Without the addition of HG, the ζ-potential of CN stabilized emulsion droplets decreased from 16.72 to −27.24 mV as the pH increased from 4 to 7, since the net electrical charge of the adsorbed CN at the droplet changed from positive to negative at pH above protein IEP (4.6–5.2) (Liu et al., 2016). With the increasing concentration of HG from 0 to 0.2 wt% at pH 4, ζ-potential values of emulsions were decreased from 16.72 to −24.53 mV, and particle sizes ranged from 4.44 to 3.96 μm, respectively, suggesting that some intermediate ‘complexes’ were formed. However, it is worth mentioning that the ζ-potential and particle size of CN stabilized emulsions were rather similar at pH 7 when HG concentration increased from 0 to 0.2 wt%. It is stated that lack of interactions between HG and CN molecules at pH 7 were due the high electrostatic repulsion between the anionic polysaccharides and negatively charged CN droplets, which is confirmed by ζ-potential data (Fig. 6A). At pH 5.5, ζ-potential and particle size were decreased from −1.84 to −35.42 mV and 4.66 to 3.52 μm as the HG increased from 0 to 2 wt%, respectively. The magnitude of ζ-potential decreased significantly (p < 0.05) at pH 5.5, indicating the presence of electrostatic interactions between CN and HG. The complexing polysaccharide was able to decrease the particle size of droplets at pH 5.5 compared to those at pH 4 and 7, which was associated with the increased steric and electrostatic repulsions between droplets and improved viscosity of continuous phase that limited the mobility of oil droplets to induce aggregation. Similarly findings were reported by Huck-Iriart et al. (2013), who showed that with the increasing concentration of xanthan gum from 0 to 5 wt% in CN stabilized emulsions, particle size of emulsions was decreased from 4.47 to 0.41 μm, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Effect of HG concentration and pH on the (A) ζ-potential and (B) particle size (d43) of CN-stabilized emulsions (1% CN, 10% corn oil, 5 mM PBS).

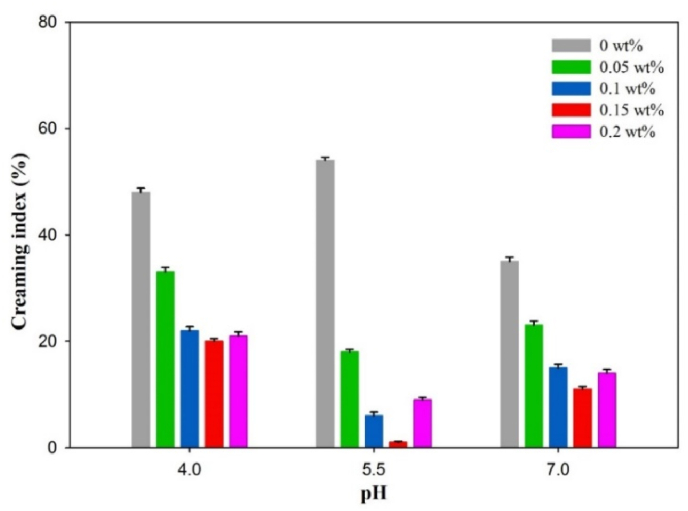

3.8. Creaming stability

Fig. 7 illustrates the influence of HG concentration on the creaming stability of emulsions at different pH values (4–7) during 21 days of storage. With the addition of low amount of HG (0.05%), emulsions showed instability, which was probably due to insufficient polysaccharide molecules to fully cover the CN-coated droplets (Li et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2012). As discussed above in phase diagram, transparent particles were present in the serum layer at pH 4 due to the formation of precipitates, which could result in the destabilization of emulsions at pH 4. The CN stabilized emulsion revealed the highest creaming index of 48% at pH 5.5, which was decreased with the addition of HG. The increase in creaming stability at pH 5.5 with the increasing HG concentration could be associated with the increased adsorption of protein molecules at the droplet surface, and producing a higher steric repulsion between droplets that inhibited droplets aggregation. The complexation of CN and HG at pH 5.5 has retarded the mobility of the emulsion droplets, and significantly enhanced emulsion stability at a lower total polymer concentration even though aggregation of droplets still occurred, as observed through microstructures. Considering the results of increased dilatational modulus of the interfacial layers, this increase in creaming stability was attributed to the increased electrostatic interactions (Liu et al., 2016). HG might increase the creaming stability due to: i) high charge density, molecular weight, and rigidity and therefore, it may adsorb to positive patches on the surface of CN-coated droplets, which leads to increase the steric and electrostatic repulsions of droplets. ii) HG efficiently improves the viscosity of aqueous phase, limiting the mobility of droplets to induce creaming (Sosa-Herrera et al., 2008; Vilela and Cunha, 2016).

Fig. 7.

Effect of HG concentration and pH on the creaming stability of CN/HG stabilized emulsions after 21 days of storage.

4. Conclusions

The present study elaborated that the magnitude of interactions between CN and HG in the emulsions are depended on the pH and relative concentration of HG in the aqueous phase. The complex interfacial layers are formed at pH 5.5, which consist of adsorption of CN at the bare oil droplets accompanied by electrostatically attached HG molecules. The results showed that the formation of CN/HG complexes at pH 5.5 increased the apparent viscosity of the emulsions as well as enhanced molecular diffusion and penetration rates of CN to the O/W interface, but decreased the rearrangement rate for the longer adsorption time. The CN/HG complexes formed thick adsorption layers around the oil droplets which significantly increased the surface dilatational modulus with the increasing concentration of HG, particularly, the elasticity of CN adsorbed layers, and progressively improved the surface protein coverage. The complexing polysaccharide was able to decrease the particle size of droplets at pH 5.5 compared to those at pH 4 and 7, which was associated with the increased steric and electrostatic repulsions between droplets and improved viscosity of continuous phase that limited the mobility of oil droplets to induce aggregation as well as the formation of a stronger viscoelastic layers at the interface. As a result, emulsions stabilized by CN/HG complexes showed significantly increased stability with the addition of lower total HG concentration (0.15 wt%) even though aggregation of droplets still occurred as observed through microstructures. This study provided valuable insights into the electrostatic interactions between CN/HG which can be used to increase the emulsions stability or fabricate delivery systems for bioactive compounds.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shahzad Farooq: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Muhammad Ijaz Ahmad: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Abdullah: Investigation, Formal analysis.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Agbenorhevi J.K., Kontogiorgos V., Kasapis S. Phase behaviour of oat β-glucan/sodium caseinate mixtures varying in molecular weight. Food Chem. 2013;138(1):630–637. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos M.A., van Vliet T. Interfacial rheological properties of adsorbed protein layers and surfactants: a review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;91(3):437–471. doi: 10.1016/s0001-8686(00)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., McClements D.J., Zhu Y., Zou L., Li Z., Liu W., Liu C. Gastrointestinal fate of fluid and gelled nutraceutical emulsions: impact on proteolysis, lipolysis, and quercetin bioaccessibility. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66(34):9087–9096. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b03003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Ma H.T., Wang L., Tan L. Viscoelastic behavior of high acyl gellan/sodium caseinate mixed gel. Modern Food Sci. Tech. 2017;33(4):101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Chu B., Zhou Z., Wu G., Farrell H.M. Laser light scattering of model casein solutions: effects of high temperature. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1995;170(1):102–112. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong S., van de Velde F. Charge density of polysaccharide controls microstructure and large deformation properties of mixed gels. Food Hydrocolloids. 2007;21(7):1172–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson E. Caseins in emulsions: interfacial properties and interactions. Int. Dairy J. 1999;9(3):305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson E. Hydrocolloids at interfaces and the influence on the properties of dispersed systems. Food Hydrocolloids. 2003;17(1):25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson E. Interfacial structure and stability of food emulsions as affected by protein–polysaccharide interactions. Soft Matter. 2008;4(5):932–942. doi: 10.1039/b718319d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doublier J.L., Garnier C., Renard D., Sanchez C. Protein–polysaccharide interactions. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000;5(3):202–214. [Google Scholar]

- Euston S.R., Hirst R.L. Comparison of the concentration-dependent emulsifying properties of protein products containing aggregated and non-aggregated milk protein. Int. Dairy J. 1999;9(10):693–701. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq S., Abdullah, Zhang H., Weiss J. A comprehensive review on polarity, partitioning, and interactions of phenolic antioxidants at oil-water interface of food emulsions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021;20:4250–4277. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh K.K.T., Haisman D.R., Singh H. Characterisation of a high acyl gellan polysaccharide using light scattering and rheological techniques. Food Hydrocolloids. 2006;20(2):176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Graham D.E., Phillips M.C. Proteins at liquid interfaces: III. Molecular structures of adsorbed films. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1979;70(3):427–439. [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., Liu Y.-C., Yang X.-Q., Jin Y.-C., Yu S.-J., Wang J.-M., Hou J.-J., Yin S.-W. Fabrication of edible gellan gum/soy protein ionic-covalent entanglement gels with diverse mechanical and oral processing properties. Food Res. Int. 2014;62:917–925. [Google Scholar]

- Hemar Y., Tamehana M., Munro P.A., Singh H. Influence of xanthan gum on the formation and stability of sodium caseinate oil-in-water emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2001;15(4):513–519. [Google Scholar]

- Huck-Iriart C., Pizones Ruiz-Henestrosa V.M., Candal R.J., Herrera M.L. Effect of aqueous phase composition on stability of sodium caseinate/sunflower oil emulsions. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013;6(9):2406–2418. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J.A., Dalgleish D.G. Adsorption behaviour of whey protein isolate and caseinate in soya oil-in-water emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids. 1994;8(2):175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins P., Snowden M. Depletion flocculation in colloidal dispersions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1996;68:57–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kobori T., Matsumoto A., Sugiyama S. pH-Dependent interaction between sodium caseinate and xanthan gum. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009;75(4):719–723. [Google Scholar]

- Lam R.S.H., Nickerson M.T. Food proteins: a review on their emulsifying properties using a structure–function approach. Food Chem. 2013;141(2):975–984. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Li K., Shen Y., Niu F., Fu Y. Influence of pure gum on the physicochemical properties of whey protein isolate stabilized oil-in-water emulsions. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016;504:442–448. [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Gillies G., Patel H., Matia-Merino L., Ye A., Golding M. Physical stability, microstructure and rheology of sodium-caseinate-stabilized emulsions as influenced by protein concentration and non-adsorbing polysaccharides. Food Hydrocolloids. 2014;36:245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Zhao Q., Liu T., Kong J., Long Z., Zhao M. Sodium caseinate/carboxymethylcellulose interactions at oil–water interface: relationship to emulsion stability. Food Chem. 2012;132(4):1822–1829. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Zhao Q., Liu T., Zhao M. Dynamic surface pressure and dilatational viscoelasticity of sodium caseinate/xanthan gum mixtures at the oil–water interface. Food Hydrocolloids. 2011;25(5):921–927. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Zhao Q., Zhou S., Zhao M. Modulating interfacial dilatational properties by electrostatic sodium caseinate and carboxymethylcellulose interactions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;56:303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen-Reynders E.H., Lucassen J., Garrett P.R., Giles D., Hollway F. Dynamic surface measurements as a tool to obtain equation-of-state data for soluble monolayers. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;144:272–285. [Google Scholar]

- Moritaka H., Nishinari K., Taki M., Fukuba H. Effects of pH, potassium chloride, and sodium chloride on the thermal and rheological properties of gellan gum gels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995;43(6):1685–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Perez A.A., Carrara C.R., Sánchez C.C., Santiago L.G., Rodríguez Patino J.M. Interfacial dynamic properties of whey protein concentrate/polysaccharide mixtures at neutral pH. Food Hydrocolloids. 2009;23(5):1253–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Picone C.S.F., da Cunha R.L. Interactions between milk proteins and gellan gum in acidified gels. Food Hydrocolloids. 2010;24(5):502–511. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Hernández A.I., Durand S., Garnier C., Tecante A., Doublier J.L. Rheology-structure properties of gellan systems: evidence of network formation at low gellan concentrations. Food Hydrocolloids. 2003;17(5):621–628. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Patino J.M., Molina Ortiz S.E., Carrera Sánchez C., Rodríguez Niño M.R., Añón M.C. Dynamic properties of soy globulin adsorbed films at the air–water interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;268(1):50–57. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9797(03)00642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosa-Herrera M.G., Berli C.L.A., Martínez-Padilla L.P. Physicochemical and rheological properties of oil-in-water emulsions prepared with sodium caseinate/gellan gum mixtures. Food Hydrocolloids. 2008;22(5):934–942. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnuolo P.A., Dalgleish D.G., Goff H.D., Morris E.R. Kappa-carrageenan interactions in systems containing casein micelles and polysaccharide stabilizers. Food Hydrocolloids. 2005;19(3):371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan M., Singh H., Munro P.A. The effect of sodium chloride on the formation and stability of sodium caseinate emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2000;14(5):497–507. [Google Scholar]

- Surh J., Decker E.A., McClements D.J. Influence of pH and pectin type on properties and stability of sodium-caseinate stabilized oil-in-water emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2006;20(5):607–618. [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.-H., Shen L. Dynamic adsorption and dilatational properties of BSA at oil/water interface: role of conformational flexibility. Food Hydrocolloids. 2015;43:388–399. [Google Scholar]

- Vilela J.A.P., Cunha R.L.d. High acyl gellan as an emulsion stabilizer. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;139:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilela J.A.P., Cunha R.L.d. Emulsions stabilized by high acyl gellan and KCl. Food Res. Int. 2017;91:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xia N., Yang X.-Q., Yin S.-W., Qi J.-R., He X.-T., Yuan D.-B., Wang L.-J. Adsorption and dilatational rheology of heat-treated soy protein at the oil–water interface: relationship to structural properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60(12):3302–3310. doi: 10.1021/jf205128v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward A.F.H., Tordai L. Time‐dependence of boundary tensions of solutions I. The role of diffusion in time‐effects. J. Chem. Phys. 1946;14(7):453–461. [Google Scholar]

- Wassén S., Lorén N., van Bemmel K., Schuster E., Rondeau E., Hermansson A.-M. Effects of confinement on phase separation kinetics and final morphology of whey protein isolate–gellan gum mixtures. Soft Matter. 2013;9(9):2738–2749. [Google Scholar]

- Ye A., Flanagan J., Singh H. Formation of stable nanoparticles via electrostatic complexation between sodium caseinate and gum arabic. Biopolymers. 2006;82(2):121–133. doi: 10.1002/bip.20465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Zhang Z., Vardhanabhuti B. Effect of charge density of polysaccharides on self-assembled intragastric gelation of whey protein/polysaccharide under simulated gastric conditions. Food Funct. 2014;5(8):1829–1838. doi: 10.1039/c4fo00019f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Zhao M., Yang B., Cui C. Effect of xanthan gum on the physical properties and textural characteristics of whipped cream. Food Chem. 2009;116(3):624–628. [Google Scholar]

- Zia K.M., Tabasum S., Khan M.F., Akram N., Akhter N., Noreen A., Zuber M. Recent trends on gellan gum blends with natural and synthetic polymers: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;109:1068–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]