Abstract

Background

Patients with extreme body mass indices (BMI) could have an increased risk of death while hospitalized for COVID-19.

Methods

The database of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) was used to assess the time to in-hospital death with competing-risks regression by sex and between the categories of BMI.

Results

Data from 12,137 patients (age 60.0 ± 16.2 years, 59% males, BMI 29.4 ± 6.9 kg/m2) of 48 countries were available. By univariate analysis, underweight patients had a higher risk of mortality than the other patients (sub-hazard ratio (SHR) 1.75 [1.44–2.14]). Mortality was lower in normal (SHR 0.69 [0.58–0.85]), overweight (SHR 0.53 [0.43–0.65]) and obese (SHR 0.55 [0.44–0.67]) than in underweight patients. Multivariable analysis (adjusted for age, chronic pulmonary disease, malignant neoplasia, type 2 diabetes) confirmed that in-hospital mortality of underweight patients was higher than overweight patients (females: SHR 0.63 [0.45–0.88] and males: 0.69 [0.51–0.94]).

Conclusion

Even though these findings do not imply changes in the medical care of hospitalized patients, they support the use of BMI category for the stratification of patients enrolled in interventional studies where mortality is recorded as an outcome.

The risks of overweight or obesity during the COVID-19 pandemic has attracted much attention. Indeed, obesity is associated with a respiratory insufficiency likely exacerbated by a COVID-19 pneumonitis or respiratory complication that may increase the need for a ventilatory support and hospital stay [1]. However, cohort studies or meta-analyses reported divergent findings supporting or refuting an obesity paradox: increased mortality of obese patients has been reported by some investigators [[2], [3], [4]] but not by others [5,6].

In contrast, a potential association between a low BMI and mortality of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 has been less extensively scrutinized [7,8]. Nevertheless, a low BMI can represent a feature of malnutrition regardless of the underlying cause [9]. Underweight and especially malnourished patients facing an acute inflammation such as COVID-19 can experience more frequent complications related to muscle weakness and immune deficiency. Older age, male gender and chronic diseases (with or without inflammatory component) are known risk factors for both malnutrition [9], and poor outcome after a COVID-19 infection.

Some investigators analyzed the association between BMI and mortality. A J-shaped curve in some [10] but not all [3] meta-analyses of these studies. If present, the confounding effect of BMI mortality should be used to stratify patients included in interventional trials.

This study aimed to assess the relation between admission BMI and in-hospital mortality in a large cohort of patients hospitalized for COVID-19, adjusting for demographic and health factors.

1. Patients and methods

We included adult patients (at least 18 years-old) included in the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) database from January 2020 to January 2021, with a value of BMI (either BMI, or weight and height reported) and the admission and outcome dates.

Patients with a BMI under 10 kg/m2 and above 100 kg/m2 were excluded (n = 27 and 58, respectively), as these values were most likely incorrect. Patients were categorized as underweight (BMI <18.5 if age ≤65 or 20.5 for an age >65 years, normal (BMI ≥18.5 or 20.5–24.99), overweight (BMI 25.00–29.99) or obese (BMI ≥30) (15).

The variables used to describe the sample included age, sex, weight, height, BMI, survival, length of hospital stay and region. Count and percentages were presented in each category of the categorical variables. Mean and standard deviation were used to describe normally-distributed data. Median and interquartile range were used to describe asymmetrical distributions. Normality was assessed based on graphical representations (histogram, box plot, qq plot). Reference values from the ISARIC report from 8 April 2021 were given as comparison.

Time-to-in-hospital-death was analyzed with competing-risks regression (according to the method of Fine and Gray), considering the discharge alive as the competing event. The proportional-subhazards assumption was verified with a test of interaction with time. A multivariable analysis, including other separately-identified predictors of in-hospital-mortality and stratified for sex (because of non-proportional subhazards) was performed. Variable selection was based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Sub-hazard ratios (SHR) were presented with their 95% confidence interval. Wald's test p-value was presented.

The analyses were performed with Stata/IC 15.1.

2. Results

Data from 12,137 patients from 48 different countries were available for analysis (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). The characteristics of the patients are displayed on Table 1 (analyzed and validation datasets). Patients were mostly middle-aged (60.0 ± 16.2 years old), predominantly male (59.0%), obese (38.8%) and hospitalized in Europe (59.3%) or North America (27.2%).

Table 1.

Description of the sample and reference values.

| N | Mean ± SD/%/Median [IQR] |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | ISARIC 8 April 2021 | ||

| Age (years) | 12,137 | 60.0 ± 16.2 | Median 61 |

| Sex | 12,092 | ||

| F | 4953 | 41.0 | 48.4 |

| M | 7139 | 59.0 | 51.6 |

| Weight (kg) | 12,137 | 83.6 ± 21.3 | – |

| Height (cm) | 12,137 | 168.4 ± 10.4 | – |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 12,137 | 29.4 ± 6.9 | – |

| BMI | 12,137 | ||

| <18.5a or <20.5b Underweight | 362 | 3.0 | – |

| ≥18.5a or ≥20.5b–24.99 Normal | 2699 | 22.2 | – |

| 25.00–29.99 Overweight | 4371 | 36.0 | – |

| ≥30 Obese | 4705 | 38.8 | – |

| Deceased | 12,137 | ||

| Yes | 2237 | 18.4 | 23.7 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 12,137 | 13 [7–20] | Median 8 |

| Region | 11,747 | ||

| Africa | 57 | 0.5 | |

| Asia | 988 | 8.4 | |

| South America | 519 | 4.4 | |

| North America | 3200 | 27.2 | |

| Western Europe | 4339 | 36.9 | |

| Eastern Europe | 2631 | 22.4 | |

| Oceania | 13 | 0.1 | |

Age≤65.

Age>65.

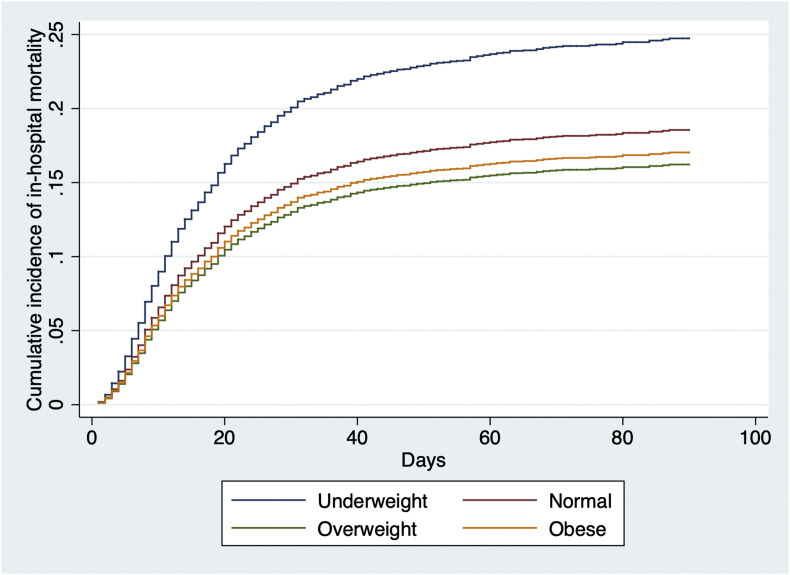

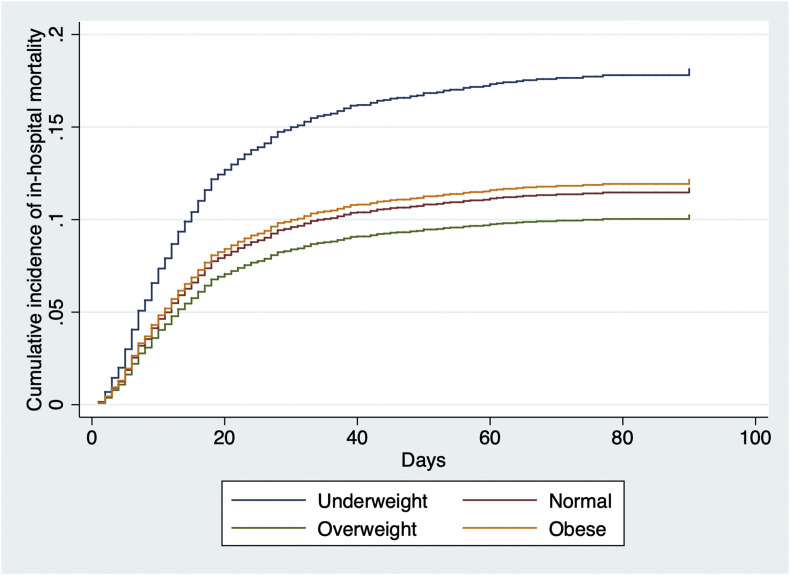

Univariate analysis showed that underweight patients had a higher risk of in-hospital mortality than the patients from all other categories of BMI combined (SHR 1.75 [95% CI 1.44–2.14]). When underweight was taken as the reference, the SHR of in-hospital mortality for the normal, overweight and obese patients were 0.69 [0.58–0.85], 0.53 [0.43–0.65] and 0.55 [0.44–0.67] respectively.

After adjustment for the other explanatory variables identified (age, chronic pulmonary disease, malignant neoplasm and type 2 diabetes), the multivariable analysis revealed that the overweight patients had still a significantly lower risk of in-hospital mortality than the underweight patients. Overall, the magnitude of the association of age with risk of death was greater in men than in women, while the opposite was found for the categories of BMI (Table 2 and Supplemental Figs. 1a and b). The only difference in statistical significance between men and women was the sub-hazard ratio for malignant neoplasm (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sub-hazard ratios of in-hospital death in women and men, by age, BMI, chronic pulmonary disease, malignant neoplasm and type 2 diabetes.

| Women n = 4378 ndeath (failure) = 635 ndischarged (competing) = 3369 |

Men n = 6231 ndeath (failure) = 1267 ndischarged (competing) = 4343 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR [95% CI] | p-value | SHR [95% CI] | p-value | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| 18–48 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 49–59 | 1.75 [1.26–2.42] | 2.18 [1.73–2.74] | ||

| 60–71 | 2.57 [1.91–3.46] | 3.26 [2.63–4.04] | ||

| 72–105 | 4.53 [3.42–6.00] | 5.79 [4.68–7.16] | ||

| BMI | 0.03 | <0.001 | ||

| Underweight | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Normal | 0.79 [0.57–1.11] | 0.92 [0.67–1.25] | ||

| Overweight | 0.63 [0.45–0.88] | 0.69 [0.51–0.94] | ||

| Obese | 0.78 [0.57–1.07] | 0.78 [0.57–1.06] | ||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.58 [1.27–1.98] | <0.001 | 1.16 [0.98–1.37] | 0.08 |

| Malignant neoplasm | 1.48 [1.17–1.88] | 0.001 | 1.03 [0.86–1.23] | 0.77 |

| Diabetes type II | 1.52 [1.29–1.79] | <0.001 | 1.28 [1.14–1.44] | <0.001 |

3. Discussion

This study was performed on data recorded in a large cohort of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in different regions of the world suggests that being overweight is associated with higher survival than being underweight, even after adjustment for chronic conditions proportionally associated with lower survival (Table 2).

The findings of a protective effect of overweight differ from other large studies; Gao et al. [2] found a linear increase in risk of severe COVID-19 leading to admission to hospital, and death, above a threshold of BMI of 23, while Ullah et al. [5] reported that morbid obesity serves as an independent risk factor of high in-hospital mortality and the need for invasive mechanical ventilation. In addition to the diverging associations between BMI and in-hospital mortality, there are several differences between the published studies: definition of BMI threshold, categorical stratification of BMI ranges, selection of confounding factors, definitions of poor outcome (length of hospital stay, vs composite index). The impact of the discrepancies of these variables if mostly unknown. Arguably, the use of the thresholds used for the GLIM classification [9] could have been used but this would not change the results of our analyses, as only 0.1% of the population would change of category of weight.

Suggested mechanistic hypotheses for the protective effect of overweight include the immunomodulatory effects of adipokines (leptin, adiponectin, resistin and visfatin) [11]. The production of TNF receptors by adipose tissue [12] might attenuate the consequences of the cytokine storm [13].

From a public health standpoint, the socio-economic condition, medical managementglobal health status of overweight patients could also be better than the other categories [14] On the other hand, potential explanations for the worsened outcome in patients with low BMI include a high rate of malnutrition-related complications such as muscle weakness and increased susceptibility to infections, although these hypotheses cannot be assessed with the available data.

The strengths of this study include the large size of the cohort of patients from the 5 continents. The characteristics of the population are consistent with other reports [6,7], including the in-hospital mortality and length of stay.

Potential limitations include the lack of data on ethnicity, an overrepresentation of Europe and North America and of obese patients, even when BMI was not reported in 95% of the patients recorded in the entire database. This high percentage of missing values possibly reflects a lack of interest for nutrition status and/or the lack of recording when the weight was considered as normal. Still, the number of patients with a complete dataset including BMI allowed a meaningful analysis.

Potential implications of these findings include the need to include the BMI range for the stratification of patients enrolled in interventional studies where in-hospital mortality is recorded as an outcome.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: Jason Bouziotis, Marianna Arvanitakis, Jean-Charles Preiser.

Methodology: Jason Bouziotis.

Formal analysis: Jason Bouziotis, Marianna Arvanitakis, Jean-Charles Preiser.

Visualization: Jason Bouziotis, Jean-Charles Preiser.

Writing - original draft: Jason Bouziotis, Marianna Arvanitakis, Jean-Charles Preiser.

Footnotes

This research was funded in part by the Wellcome Trust [Grant number 215091/Z/18/Z]. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2022.01.017.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

figs2.

References

- 1.Chetboun M., Raverdy V., Labreuche J., Simonnet A., Wallet F., Caussy C., et al. BMI and pneumonia outcomes in critically ill COVID-19 patients: an international multicenter study. Obesity. 2021;29:1477–1486. doi: 10.1002/oby.23223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao M., Piernas C., Astbury N.M., Hippisley-Cox J., O'Rahilly S., Aveyard P., et al. Associations between body-mass index and COVID-19 severity in 6·9 million people in England: a prospective, community-based, cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:350–359. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du Y., Lv Y., Zha W., Zhou N., Hong X. Association of body mass index (BMI) with critical COVID-19 and in-hospital mortality: a dose-response meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2021:117. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendren N.S., de Lemos J.A., Ayers C., Das S.R., Rao A., Carter S., et al. Association of body mass index and age with morbidity and mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: results from the American heart association COVID-19 cardiovascular disease registry. Circulation. 2021;143:135–144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.051936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ullah W., Roomi S., Nadeem N., Saeed R., Tariq S., Ellithi M., et al. Impact of body mass index on COVID-19-related in-hospital outcomes and mortality. J Clin Med Res. 2021:13. doi: 10.14740/jocmr4239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng L., Zhang J., Wang M., Chen L. Obesity is associated with severe COVID-19 but not death: a dose−response meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect. 2021:149. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820003179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caccialanza R., Formisano E., Klersy C., Ferretti V., Ferrari A., Demontis S., et al. Nutritional parameters associated with prognosis in non-critically ill hospitalized COVID-19 patients: the NUTRI-COVID19 study. Clin Nutr. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ochoa J.B., Cárdenas D., Goiburu M.E., Bermúdez C., Carrasco F., Correia M.I.T.D. Lessons learned in nutrition therapy in patients with severe COVID-19. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020;44 doi: 10.1002/jpen.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cederholm T., Jensen G.L., Correia M.I.T.D., Gonzalez M.C., Fukushima R., Higashiguchi T., et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition – a consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang H.K., Bukhari K., Chiung-Hui Peng C., Hung D.P., Shih M.C., Huai-En Chang R., et al. The J-shaped relationship between body mass index and mortality in patients with COVID-19: a dose-response meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metabol. 2021;23:1701–1709. doi: 10.1111/dom.14382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Post A., Bakker S.J.L., Dullaart R.P.F. Obesity, adipokines and COVID-19. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020:e13313. doi: 10.1111/eci.13313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohamed-Ali V., Goodrick S., Bulmer K., Holly J.M., Yudkin J.S., Coppack S.W. Production of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors by human subcutaneous adipose tissue in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1999 Dec;277(6):E971–E975. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.6.E971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nie W., Zhang Y., Jee S.H., Jung K.J., Li B. Obesity survival paradox in pneumonia: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2014;12:61. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arbel Y., Fialkoff C., Kerner A., Kerner M. Can reduction in infection and mortality rates from coronavirus be explained by an obesity survival paradox? An analysis at the US statewide level. Int J Obes. 2020;44:2339–2342. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-00680-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.