Abstract

单纯疱疹病毒(HSV,包括HSV-1和HSV-2)是引起多种疾病的重要病原,通常这些疾病具有反复发作和无法根治的特点。HSV在外周黏膜组织表面进行增殖式感染后,可进入感觉神经元并建立无复制的潜伏感染。潜伏的病毒还可以通过激活的方式重新进入复制周期,并回到外周组织进行复发感染。这种既能通过潜伏逃避宿主免疫攻击又能在激活过程中传播的能力是该病毒高超的生存策略,也是当前任何药物无法彻底消灭该病毒的根本原因。虽然HSV潜伏与激活的研究众多,且不断有新的研究进展,但由于潜伏和激活过程本身的复杂性和研究模型的局限性,其中很多具体过程相关机制依然不明确,甚至常有争议。本文重点梳理HSV-1潜伏和激活的主要研究成果,并讨论其发展趋势。

Abstract

Herpes simplex virus (HSV), including HSV-1 and HSV-2, is an important pathogen that can cause many diseases. Usually these diseases are recurrent and incurable. After lytic infection on the surface of peripheral mucosa, HSV can enter sensory neurons and establish latent infection during which viral replication ceases. Moreover, latent virus can re-enter the replication cycle by reactivation and return to peripheral tissues to start recurrent infection. This ability to escape host immune surveillance during latent infection and to spread during reactivation is a viral survival strategy and the fundamental reason why no drug can completely eradicate the virus at present. Although there are many studies on latency and reactivation of HSV, and much progress has been made, many specific mechanisms of the process remain obscure or even controversial due to the complexity of this process and the limitations of research models. This paper reviews the major results of research on HSV latency and reactivation, and discusses future research directions in this field.

Keywords: Simplexvirus, Infection, Gene expression, Trigeminal ganglion, In situ hybridization , Transcriptional activation, Immunohistochemistry, Review

单纯疱疹病毒(herpes simplex virus, HSV)属疱疹病毒科,是具有囊膜(envelope)的双链线性DNA病毒,基因组约为152 kb,GC(鸟嘌呤和胞嘧啶)含量高,约占68%。疱疹病毒的平均直径约为185 nm,核心为双链DNA,其外由162个衣壳蛋白分子组成的衣壳(capsid)包裹,间质(tegument)位于衣壳与囊膜之间(包含至少18种病毒蛋白),最外层为至少13种病毒糖蛋白组成的双层脂质囊膜结构。无论从膜蛋白的定位还是数量来看,其均为病毒感染机体时被免疫系统识别的重要抗原分子。HSV-1和HSV-2为两种血清型,现在被分类为两种病毒,它们在氨基酸序列上有83%的同源性 [ 1] 。HSV-1和HSV-2分别倾向于感染面部和生殖器,HSV-1主要引起口唇疱疹和角膜炎,而HSV-2则是生殖器疱疹的主要病原体。但这两种病毒引起的疾病并没有绝对的界限,如它们都可引起新生儿疱疹 [ 2] ,由HSV-1引起生殖器疱疹的病例也日益增多 [ 3] 。据流行病学调查数据和统计数学模型推算,世界范围内HSV-1和HSV-2的流行率分别为67% [ 4] 和11.3% [ 5] ,由HSV-1或HSV-2引起的新生儿疱疹每年的发生率约为万分之一 [ 6] 。HSV-1引起的疱疹性角膜炎是全球致盲的主要原因 [ 7] 。由HSV-1引起的脑炎,虽然每年在每10~25万人中只有一例,但该病即使及时治疗,病死率依然高达30%,且多数患者有神经性后遗症 [ 8, 9] 。

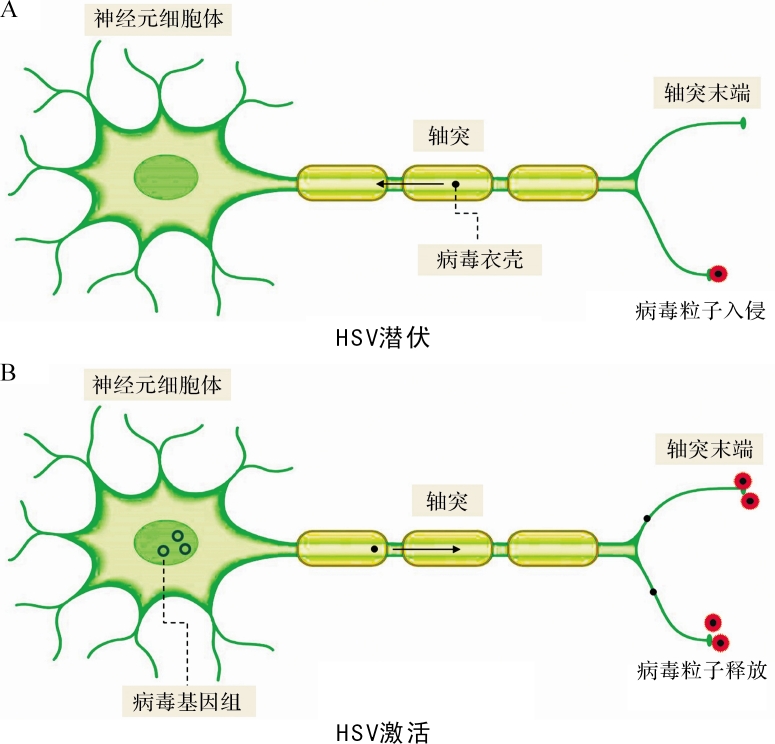

HSV可以进行两种不同形式的感染:裂解性感染(常称增殖式感染, lytic infection)和潜伏性感染(latent infection)。HSV接触宿主后,首先在外周黏膜组织的上皮细胞中进行裂解感染。该过程中病毒基因表达具有严格的时序性以及级联调控的特征,HSV的基因也因此被分为即早期基因(immediate early, IE)、早期基因(early, E)和晚期基因(late, L)。在裂解感染过程中,首先病毒粒子携带间质蛋白VP16与宿主蛋白Oct-1和宿主细胞因子1(HCF-1)形成复合物,并结合到五个即早期病毒基因( ICP0、 ICP4、 ICP22、 ICP42、 ICP47)的启动子后启动转录;随后,表达的即早期蛋白质启动早期基因表达和病毒基因组复制;最后晚期基因表达被启动。HSV感染外周组织后,一部分病毒接触到外周神经元(主要为感觉神经元)的轴突,沿轴突逆行至胞体,并建立潜伏感染 [ 2] (图 1病毒潜伏部分)。经典病毒学认为,HSV潜伏感染具有以下特点 [ 2] :病毒能在宿主体内持续存在,但宿主本身不表现任何临床症状;病毒可由潜伏状态被激活(reactivated,再激活)并伴随具感染力的病毒粒子产生;病毒不表达任何增殖式循环相关基因(简称裂解基因),但在细胞核内会大量积累潜伏相关转录本(latency-associated transcript, LAT);病毒不表达相关抗原,但宿主体内可检测到病毒基因组的存在。HSV-1和HSV-2分别主要潜伏于三叉神经节和骶神经节,HSV在神经细胞内建立潜伏感染,利用神经细胞具有低活跃度的代谢特点,HSV的抗原不易呈递给免疫细胞,从而逃逸免疫识别。当宿主免疫力下降或受到应激因素刺激时,病毒会在神经节内重新复制,然后经神经元轴突移至皮肤黏膜表面激活,形成复发感染(图 1病毒激活部分)。这种生命循环赋予了HSV既能逃避宿主免疫和药物治疗,又能大规模感染人类的能力,而这也是HSV经过长期进化获得的不可或缺的生存本领。

图1 .

单纯疱疹病毒在神经元中潜伏和激活的过程

1 单纯疱疹病毒潜伏机制研究

目前,人们对潜伏建立与维持过程的认识依然十分有限,虽然提出了很多假说,但目前并无某种假说能完全解释HSV潜伏,或许HSV潜伏是多种机制共同作用的结果。调控HSV潜伏的因子分为病毒因子和宿主因子,其中病毒因子主要包括LAT和一些微小RNA(miRNA,miR),而宿主因子主要包括神经元抑制因子、表观遗传调控和免疫系统控制等。

1.1 病毒LAT的功能

LAT为LAT转录区域表达的一系列长链非编码RNA,是HSV潜伏期间唯一大量存在的病毒基因产物。8.3 kb的LAT原始转录本被剪接成稳定的1.5 kb和2 kb主要LAT内含子,以及一个6.3 kb的小LAT外显子,其中2 kb内含子表达量最高 [ 2] ,另有很多小RNA从该区域生成 [ 10, 11] 。该区域也有编码蛋白质相关报道,但尚无其发挥作用的证据 [ 12, 13] 。

LAT的研究历程可以追溯到1979年,当时在人椎旁神经元尸检切片中利用原位杂交实验发现了HSV衍生出的RNA [ 14] 。1987年,Stevens等 [ 15] 通过原位杂交法和RNA印迹法对LAT的位置进行精确定位,并找到了位于与ICP0反义位置的2.0 kb LAT内含子,提出LAT通过反义抑制ICP0表达来促进潜伏的观点。ICP0是启动病毒基因表达重要的病毒蛋白质 [ 16] ,对其抑制可以很好地解释潜伏期间病毒基因表达的沉默。随着LAT相关研究增多,人们也构建出了许多LAT缺失病毒。

然而LAT似乎并没有想象中那么重要。对于病毒潜伏的建立、维持和激活,LAT不是必需的 [ 17, 18, 19] ,其反义抑制ICP0的现象只在某些细胞系中观察到 [ 20] ,并未在动物体内或其他细胞系中看到 [ 13, 21] 。有研究报道LAT的缺失在小鼠三叉神经节中引起裂解基因表达水平的升高 [ 22, 23, 24] ,以及异染色质在裂解基因启动子上的富集 [ 25, 26] ,然而在兔三叉神经节中LAT的缺失反而引起一些裂解基因转录本水平降低 [ 27] 。

目前发现激活频率下降是LAT缺失病毒最一致的表型 [ 28, 29, 30, 31] ,这似乎与LAT促进潜伏的假设相悖。因为LAT缺失病毒会在更少的神经元中建立潜伏感染 [ 32, 33] ,而建立潜伏感染的神经元数量与激活频率相关 [ 34] ,因此激活频率下降可能反映了潜伏建立的缺陷而不是对激活的直接影响。为解决该问题,Nicoll等 [ 24] 用Ai6 ZsGreen转基因小鼠和Cre重组酶表达病毒标记成功建立了潜伏感染的神经元,而在这些单个神经元中,LAT的缺失可对应激活频率的升高。但与此结果相反的是,即使在潜伏建立水平相似的情况下,一些实验仍然发现LAT缺失病毒存在激活方面的缺陷 [ 35, 36] ;Watson等 [ 37] 通过兔模型发现,潜伏建立后核酶酶解LAT降低了激活水平。另外,Perng等 [ 38] 发现LAT的缺失增加了细胞凋亡,且在重组病毒基因组中,用具有抗凋亡活性的潜伏相关基因代替LAT基因可以达到野生型激活水平 [ 39] ,从而用细胞死亡解释激活水平下降的表型。虽然也有其他报道支持LAT促进神经元存活的观点 [ 40, 41] ,但对其在凋亡中的作用却提出质疑 [ 40] 。宏观角度上神经元的存活对病毒建立足够水平的潜伏以备后续激活是有利的,所以LAT缺失病毒在建立潜伏、激活和维持潜伏时基因组稳定性上的缺陷可能都反映了LAT对神经元的保护作用 [ 42, 43] 。

总之,从目前的研究结果来看,LAT虽然对病毒潜伏和激活来说并不是必要的,但在这些过程中确实发挥功能,至少其在保护神经元和抑制裂解基因表达方面的作用是被学者普遍认可的,而且LAT的缺失在很多结果中影响激活,虽然这是否归结于LAT对激活本身的影响尚无法确定。

1.2 病毒miRNA的功能

目前已发现29种HSV-1或HSV-2编码的miRNA [ 44, 45, 46, 47, 48] ,其中miR-H2、H4~H7是在HSV潜伏过程中除LAT外大量存在的病毒基因产物,不仅在潜伏感染的小鼠三叉神经节中高表达 [ 49, 50, 51] ,而且存在于原代培养神经元的潜伏模型中 [ 51] ,甚至在人类尸体的三叉神经节中也高表达 [ 52] 。

这些miRNA在潜伏期间的高表达严格依赖于LAT启动子 [ 49] ,说明这些miRNA很可能是由LAT原始转录本剪切形成,这激起了人们用这些miRNA解释LAT的一些功能,尤其在调控基因表达方面功能的兴趣。有趣的是,无论是在HSV-1还是HSV-2中,miR-H2与ICP0转录本完全互补,并能在细胞转染实验中抑制ICP0表达 [ 45, 48, 53] 。miR-H3、miR-H4均与病毒的神经毒力因子ICP34.5的转录本完全互补,并在转染实验中下调其表达 [ 47, 48, 54] ,人们猜想其可以通过减少神经元死亡来促进潜伏 [ 45] 。

然而目前这些miRNA在体内的重要作用尚缺乏有力证据。Jiang等 [ 55] 报道HSV-1 miR-H2缺失会导致小鼠神经毒力和激活能力上升,但本课题组利用另一种病毒株和小鼠品系并未见miR-H2缺失病毒相应的明显表型 [ 53] 。分别缺失了miR-H2、H3、H4或H6的一系列HSV-2病毒株也未在豚鼠感染模型中呈现任何与野生型差别的表型,这些结果否定了上述miRNA的重要性。然而从其在潜伏期间高表达,在体外抑制裂解基因表达,及在HSV-1和HSV-2间保守的事实看,我们倾向于认为这些miRNA在潜伏过程中发挥了作用,只是功能的冗余性和实验模型的局限性使这些功能尚未在动物实验中表现出来。

1.3 宿主神经元抑制因子作用

HSV选择性潜伏于神经元,说明存在神经特异性机制帮助潜伏。HSV从外周组织接触到轴突末端后,通过膜融合进入神经元,然后衣壳由微管介导沿轴突被逆向传输至细胞核,并从核孔向核内释放基因组(图 1病毒潜伏部分) [ 56] 。有假说认为具有长轴突的感觉神经元结构辅助了潜伏的建立。有证据证明间质蛋白VP16在轴突传输过程中与衣壳分离,无法有效到达细胞核 [ 57] ,这也与报道的从轴突末端进入的病毒倾向于直接进入非复制模式的现象相符 [ 58, 59] 。有学者提出VP16的一个辅助因子Oct-1在神经元中表达水平较低 [ 60] ,而其另一个辅助因子HCF在感觉神经元中主要定位于细胞质,无法有效地与VP16在核内形成复合物 [ 61] 。而神经元的一些其他转录因子,如Oct-2、N-Oct3,可以通过结合于Oct-1相同的DNA结合位点,竞争性地抑制Oct-1的活性 [ 60, 62] 。

神经元促进HSV潜伏并非只有上述方式。有人基于上述通路提出病毒进入神经元后默认进入潜伏状态的模型 [ 11] 。然而对该模型提出质疑的是HSV进入感觉神经元后需要经历几天复制才会完全进入无复制状态,而这段时间内VP16应该是表达的。为了分析HSV潜伏前是否经历裂解基因表达的问题,Proença等 [ 63, 64] 将在不同病毒启动子驱使下表达Cre重组酶的HSV与Cre报告小鼠结合,来标记潜伏感染的细胞中曾经发挥活性的启动子,结果表明一部分潜伏感染的细胞在建立潜伏之前就有即早期基因启动子发挥活性,说明另有机制沉默了神经元中已经表达的裂解基因。本课题组发现神经细胞中特异性高表达的宿主miR-138在HSV-1和HSV-2的ICP0转录本3′未翻译区都有结合位点,而且与HSV-1结合位点突变病毒在小鼠三叉神经节中显示裂解基因表达水平和小鼠死亡率升高,说明miR-138可以通过直接结合ICP0 mRNA下调裂解基因表达并促进宿主存活 [ 65] 。Shu等 [ 66] 发现,在神经元细胞中,当蛋白质合成被抑制或受到感染的状态下,可诱导产生大量激活转录因子3(ATF3),在受感染的细胞中,ATF3通过作用于LAT前体RNA启动子中的应答元件来增强LAT的积累,而且ATF3在维持潜伏状态中起关键作用。

我们将所有神经元一致对待显然是忽略了问题的复杂性,有证据表明HSV-1和HSV-2分别倾向于在A5和KH10阳性的神经元亚群体中表达LAT并建立潜伏 [ 67, 68, 69] ,凸显了宿主因子在HSV潜伏过程中的重要作用,然而其机制至今不明。

1.4 宿主表观遗传的调控作用

HSV潜伏期间,病毒基因组以非整合的环状游离体(episome)状态与组蛋白一起组装成核小体,稳定存在于神经元细胞核中 [ 70] 。裂解基因与富含H3K9me3(组成性异染色质标签)和H3K27me3(功能性异染色质标签)修饰的组蛋白结合形成不利于转录的异染色质 [ 71, 72, 73, 74] ,而LAT基因是病毒基因组中唯一富集乙酰化H3K9和H3K14等常染色质修饰的基因组区域 [ 75, 76, 77] ,这与潜伏期间病毒基因转录基本局限于LAT转录区域相符。激活过程中,这种模式被逆转,裂解基因和LAT基因分别表现出常染色质水平升高和降低 [ 78] 。此外,在潜伏与激活过程中发挥作用的病毒基因产物LAT和ICP0,及宿主因子HCF-1和CTCF都对病毒基因组上的染色质结构有调节作用 [ 79, 80, 81, 82, 83] 。因此,尽管人们至今对这些表象差异背后的分子机制所知甚少,表观遗传学调控作用仍被视作调控裂解感染、潜伏感染和激活之间相互转化的重要因素。

1.5 宿主免疫系统的调控作用

现有研究显示,宿主免疫系统对HSV潜伏具有促进作用。小鼠和人三叉神经节中的HSV-1潜伏感染均伴随着CD8 +T细胞浸润和相关细胞因子水平升高 [ 84, 85] ,提示CD8 +T细胞可能在潜伏中发挥作用。Knickelbein等 [ 86] 发现CD8 +T细胞产生的裂解性小颗粒并不会诱导潜伏感染神经元凋亡,且CD8 +T细胞产生粒酶B可以降解病毒ICP4蛋白质,支持宿主免疫系统以非裂解细胞的方式促进潜伏并抑制激活的假说。在小鼠中,大多数三叉神经节浸润的CD8 +T细胞对HSV-1具有特异性,约50%的CD8 +T细胞可以识别HSV-1糖蛋白gB上的特异性表位 [ 87, 88] 。gB是晚期蛋白质,因此在CD8 +T细胞发挥作用以前已经发生了一定规模的裂解基因表达。Frank等 [ 89] 发现在HSV-1特异性CD8 +T细胞成熟过程中,缺乏CD4 +T细胞会导致记忆T细胞群呈现短暂的部分耗竭,并表现出PD-1水平升高,且记忆T细胞亲和力降低,导致神经节减弱了对HSV-1潜伏的控制能力。从进化角度讲,人类的免疫系统未获得清除潜伏感染HSV的能力,反而可以促进潜伏,也许是机体减轻自身负担最便捷的方式,同时HSV潜伏感染也是进化得来利于生存的方式。

2 单纯疱疹病毒激活机制研究

2.1 自发性激活

激活是在某种因素诱发下潜伏的病毒进入复制循环,并从神经元回到外周组织进行复发感染的过程。值得注意的是,在没有触发因素或者触发因素不明确的情况下,激活也在一定基线水平上发生,这种现象称为自发性激活。自发性激活在人类感染中时有发生,在兔、豚鼠、树鼩模型也可见到 [ 90] 。然而在小鼠模型中,发生自发激活并产生感染性病毒的情况较罕见 [ 91] 。但在潜伏感染的小鼠模型中依然有低水平的裂解基因转录。一项单细胞病毒转录分析发现,虽然在潜伏感染的小鼠模型中裂解基因转录水平较低,但是在超过三分之二潜伏感染的神经元中可以检测到裂解基因转录本 [ 92] 。虽然我们尚未发现这些转录本被翻译的直接证据,但可以持续检测到潜伏期间病毒抗原特异性T细胞 [ 93] ,而且近期Russell等 [ 94] 用报告基因实验证明潜伏过程中裂解基因的启动子可以驱动蛋白质表达。这些现象可以被解释为潜伏是一个低水平存在的激活持续失败状态,当调控病毒潜伏的因子发生改变而无法阻断激活时,基因表达水平升高,大规模激活才被启动。总之,潜伏与激活的界限或许并不像传统认为的那么绝对。

2.2 诱导性激活

诱导性激活是疾病复发的重要原因,也是激活研究的主要方面。早期研究重点关注激活受哪些病毒或宿主因子的影响。除了之前提及的LAT,病毒基因ICP0和VP16及病毒DNA复制也可影响激活 [ 82, 95, 96, 97, 98] 。然而Thompson等 [ 99, 100] 利用小鼠热激模型提出激活初期的病毒蛋白质表达既不依赖于ICP0也不依赖于病毒DNA复制,却依赖于VP16 [ 101] 。Kim等 [ 102] 根据原代神经元模型中的证据提出:激活分为两个阶段,第一阶段是在某种刺激下对病毒基因表达的抑制作用被随机性解除,该阶段的基因表达不遵循级联式调控且不依赖于病毒蛋白质;第二阶段是全面病毒基因表达和感染性病毒粒子复制。激活对ICP0、VP16等病毒蛋白质的依赖可能是第二阶段的现象。

激活对一些宿主基因包括HCF-1、神经生长因子(NGF)及CTCF的依赖性也有报道。HCF-1可以在激活过程中从神经元的高尔基体向细胞核重新定位并结合即早期基因启动子 [ 61, 103] ,可以向即早期启动子招募LSD1蛋白质以逆转组蛋白甲基化对基因表达的抑制 [ 104] ,可以协同在转录延伸过程中非常重要的复合物SEC-P-TEFb促进HSV激活 [ 105] 。NGF对激活有抑制作用 [ 106] ,而该作用至少部分归结于NGF结合TrkA受体酪氨酸激酶后所激发的磷脂酰肌醇3激酶(PI3-K)通路的活化 [ 107] 。不同实验室分别报道了CTCF有促进激活 [ 83] 和抑制激活 [ 108] 的作用,其具体作用尚待进一步研究。

这些结果揭示了一些影响激活的因素,却并没有对如何触发激活这一根本问题给出答案。至少在小鼠中,潜伏期间病毒蛋白质被认为基本不表达,所以激活一般认为是在没有病毒蛋白的情况下由细胞机制所诱导的。

在人类自然感染中,紫外线、情绪紧张、发烧、组织破损、免疫抑制等因素可以诱导激活。很多诱发因素与应激过程有关,因此学者们一直在寻找应激与激活的联系。应激的机制非常复杂,其涉及交感神经-肾上腺髓质系统、下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺皮质系统和下丘脑-垂体-甲状腺轴,可以增加血液中肾上腺素和动脉肾上腺素的水平 [ 109, 110] 。人们研究时会选用热应激、环磷酰胺、地塞米松、肾上腺素和UV-B等多种刺激物诱导HSV激活,不同激活条件下,激活的模型会有不同的表型和机制。其中ICP4 mRNA在高温、低温、疲劳和免疫抑制应激因子诱导的小鼠中均有表达。Huang等 [ 111] 在小鼠体内三叉神经节中建立HSV-1潜伏感染的动物模型,使用环磷酰胺对小鼠模型进行免疫抑制,在三叉神经节区域也检测到病毒抗原。在紫外线照射下,HSV可以被诱导激活并返回小鼠眼部 [ 112] 。Washington等 [ 108] 用肾上腺素离子导入法证明绝缘体蛋白CTCF的缺失可以导致体内HSV-1的激活。

有学者认为应激过程通过激素调节病毒激活 [ 113, 114] 。Sinani等 [ 115] 发现应激因子可以刺激ICP0的表达。重要的是,Cliffe等 [ 116] 发现应激应答过程中常见的c-Jun N端激酶神经元通路为HSV激活所必需,而该通路通过组蛋白由甲基化向磷酸化的转变来促进病毒基因表达,从而将应激与病毒基因表达的启动联系起来。

3 单纯疱疹病毒潜伏和激活的模型研究

3.1 HSV潜伏和激活的动物模型研究

人类是HSV的唯一自然宿主,任何动物模型都无法完全重现人类感染,但有一些动物模型可以模拟潜伏感染与激活的过程,最常用的是小鼠模型。将病毒溶液加在用针尖划破的眼角膜、胡须垫或足垫等处的表面,病毒先后在外周组织和对应的神经节处产生急性感染,随后具有感染性的病毒水平降低,LAT水平升高,一个月之内病毒便可稳定建立潜伏感染 [ 117] 。在小鼠模型中潜伏感染稳定建立后,很难再检测到感染性病毒,这与HSV感染人时常有自发性激活的情况不同。

在研究激活的实验中,大部分实验室用体外神经节培养的方法,但也有人用热激或紫外线照射的方法进行体内激活 [ 118, 119] 。从自发性激活的意义上讲,通常认为针对HSV-1的兔角膜感染模型和HSV-2的生殖器感染豚鼠模型是较好的模型 [ 120, 121] 。此外,HSV-1的自发性激活不仅与宿主类型有关,也与病毒本身建立潜伏的株型有关 [ 122] 。如大多数HSV-1病毒株在近交系BALB/c小鼠中比近交系C57BL/6小鼠更容易再激活,通常认为这是由宿主小鼠免疫系统差异引起 [ 123] 。Hill等 [ 124] 用兔的潜伏模型发现,Macintyre和CGA-3病毒株表现出非常低的自发激活或不能被诱导激活。SC16病毒株呈现出适度的自发激活和诱导激活。Rodanus、RE、F和KOS病毒株均表现出自发性再激活,而诱导激活能力差。McKrae、17Syn +和E-43病毒株均表现出自发和诱导激活的特点。

研究HSV潜伏和激活时使用小鼠或兔建立动物模型均有其特殊的应用优势。利用小鼠建立潜伏感染模型的优势是容易获得小鼠的近交和突变品系,易于饲养且成本低,但是小鼠模型的缺点是HSV在啮齿类动物与人体内表达的病毒因子可能不同,导致病毒在啮齿类动物模型中的感染情况不同于人类 [ 120] 。兔相较于小鼠有更大的眼睛,从而更容易用来检测和评估损伤。但是近交系兔模型非常昂贵,而且很难获得,同时有基因修饰的兔模型也十分有限。但近年研究发现,灵长类动物树鼩能够更好地模拟HSV-1潜伏感染的机制 [ 90] 。Li等 [ 90] 使用眼角膜接种法,在感染后第四周树鼩的三叉神经节中检测到HSV-1的DNA,并且在体外激活实验中获得与小鼠模型类似的激活时间和病毒的细胞病变效应状态。然而,树鼩与小鼠在HSV-1关键基因的表达上存在差异,包括ICP0、ICP4和LAT。但使用树鼩模型可以获得低频率自发激活的HSV-1。更为不同的是,在树鼩模型中HSV接种后仅表现出轻微的急性感染,而没有从感觉神经元中检测到传染性的病毒,这种温和的感染更类似于人类的感染。所以,树鼩模型将可能成为研究HSV潜伏和激活的更优质模型。

3.2 HSV潜伏和激活的细胞模型研究

动物模型固然更接近自然感染,但细胞模型具有操控性强和可使用高剂量病毒感染等优点,同样便于机制研究。使用缺失即早期基因的重组病毒在非神经细胞内建立细胞模型,其病毒基因组具有可持续的非复制状态 [ 125, 126] ,虽然该模型揭示的基因调控机制或许有借鉴价值,但其在研究潜伏中的价值遭受质疑,因为这种病毒基因组既不表达LAT也不能被激活。也有研究报道,在大鼠神经分化细胞PC12(pheochromocytoma)上,也可建立HSV-1的长期非复制状态的细胞模型,PC12细胞不仅有神经元的特点,而且这种静息感染模型既能够表达HSV-1潜伏感染的标志型产物,又能够被诱导再激活,也是一种用于研究HSV-1潜伏感染和激活的模型 [ 127] 。人们将这类在细胞系中建立的使HSV-1具有可持续非复制状态的模型称为静态性感染模型,以便与真正意义的潜伏感染区别。Wilcox等 [ 128] 用胚胎大鼠交感神经节提纯的原代神经元建立了潜伏感染模型,为理解激活机制做出了贡献 [ 102, 107, 116] 。Katzenell等 [ 68] 利用成年小鼠三叉神经节建立感染模型,并在Leib等 [ 129] 实验室中推广。在此神经元培养的基础上,Enquist课题组建立了将神经元的轴突与细胞体分开的隔间培养装置 [ 130] ,并用此模型研究病毒的感染和潜伏中的重要问题 [ 131, 132] 。这些模型中的病毒可以建立高表达LAT的潜伏感染,也可从潜伏中激活,然而这些模型通常依赖抗病毒药阿昔洛韦对病毒复制的阻断从而建立潜伏,同时又缺少获得性免疫的环境,所以无法完全复制动物中的潜伏和激活过程。

4 展望

随着研究不断深入,HSV潜伏和激活问题变得越来越复杂,人们解决的问题远比发现的新问题少。当人们首次发现潜伏的标志性分子LAT时,以为找到了问题的答案,可是后来发现LAT缺失病毒呈现的表型常常与预料相反。现在我们大致了解了LAT的缺失在动物模型中的作用,但对LAT的具体功能依然没有形成清晰的认识,而且在很多具体问题上存在争议。如LAT的缺失在大部分实验中导致激活频率的变化,但这种表型反映的是对激活本身的影响还是由不同潜伏建立水平所导致的次级影响依然不确定。而且LAT转录区域编码多种序列重叠的长链非编码RNA和miRNA,而实验中用的LAT缺失病毒往往缺失多种分子,所以明确到底是哪种分子导致的表型变化是研究LAT功能的第一步,而这需要构建特异性缺失某种分子的重组病毒。相比之下,我们对LAT的作用机制了解更少。我们假设最终确定2.0 kb LAT内含子有促进激活的作用,那么它是以何种分子机制发挥这种长链非编码RNA的作用,至今我们尚未看到有任何报道在提出LAT功能的同时从分子机制角度对其解释,也未看到关于LAT与任何其他分子相互作用的报道,这方面可能是将来研究中需要强化的部分。由于LAT是HSV唯一在潜伏期间特异性高表达的分子,因此潜伏和激活的大部分研究合理聚焦在LAT上,其他研究也以病毒基因产物为主要对象。

然而,我们现在越来越清晰地认识到,HSV潜伏和激活并非某病毒基因可以独立促成的,而是病毒与宿主相互作用的结果。所以,对于病毒的潜伏研究也许会越来越多地向宿主本身靠近,如宿主如何帮助病毒建立潜伏及参与激活。同时随着生物技术的发展,各种高通量筛选试验和组学研究会帮助我们找到更多宿主与病毒相互作用的关系。随着表观遗传学的发展,会有更多不同视角的解决方案来攻克HSV的潜伏和激活。基于病毒所处的免疫监控环境,我们应该更好地利用宿主免疫系统来改造病毒所处的潜伏和激活环境。我们现有抗病毒药物一般都是通过干扰病毒本身来治疗感染,如直接抑制病毒复制、干扰病毒吸附、防止病毒穿透细胞及抑制病毒生物合成和释放,但是这些方式都无法达到根除病毒的目的,这是否也反向预示着我们应该转变研究方向。如果有了上述研究,我们会获得越来越多具有针对性的可干预靶点,这些靶点也许会为我们治疗HSV感染及复发提供重要落脚点。

潜伏和激活在研究方法学方面也有一定发展空间。过去的研究过度依赖以小鼠为主的小动物模型,不同的动物、病毒株和感染途径可以导致不同的实验结果是其原因之一。但只有在多种动物模型中得到相同的结论才更有说服力。即使如此,动物模型能提供的证据对于人类疾病来说能有多大程度的相关度也依然是个主要问题。学者利用人尸体检验所获神经节进行组织培养实验 [ 133] ,但这种标本很难获得。虽然有些实验室建立了原代神经元培养模型,但是这些研究主要用的依然是小鼠或大鼠神经节中提取的神经元。如何建立一种用人的神经元进行实验的方法将是重要的课题。

近年来,随着人类生活环境的改变以及社会压力的增大,HSV引起的疾病已成为人们广泛关注的问题。因其高超的逃避免疫和药物治疗能力,HSV将在未来很长时间里成为人类的重要病原体,如何理解并战胜HSV也将是医学界持续的课题。相信随着技术的进步和学者们共同的努力,HSV潜伏和激活机制的神秘面纱将会逐渐解开。

参考文献

- 1.DOLAN A, JAMIESON F E, CUNNINGHAM C, et al. The genome sequence of herpes simplex virus type 2. J Virol. 1998;72:2010–2021. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2010-2021.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ROIZMAN B K D M, WHITLEY R J. //KNIPE D M H P, GRIFFIN D E. Fields virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. Herpes simplex viruses; pp. 2501–2601. [Google Scholar]

- 3.BERNSTEIN D I, BELLAMY A R, HOOK E W, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(3):344–351. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LOOKER K J, MAGARET A S, MAY M T. et al. Global and regional estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type. J/OL PLoS One. 2015;10(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LOOKER K J, MAGARET A S, TURNER K M, et al. Global estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type. J/OL PLoS One. 2015;10(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LOOKER K J, MAGARET A S, MAY M T. et al. First estimates of the global and regional incidence of neonatal herpes infection. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(3):e300–309. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30362-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FAROOQ A V, SHUKLA D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57(5):448–462. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MICHALICOVÁ A, BHIDE K, BHIDE M, et al. How viruses infiltrate the central nervous system. Acta Virol. 2017;61(4):393–400. doi: 10.4149/av_2017_401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHITLEY R J. Herpes simplex virus infections of the central nervous system. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2015;21(6):1704–1713. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.PHELAN D, BARROZO E R, BLOOM D C. HSV1 latent transcription and non-coding RNA: a critical retrospective. J Neuroimmunol. 2017;308:65–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NICOLL M P, PROENÇA J T, EFSTATHIOU S. The molecular basis of herpes simplex virus latency. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36(3):684–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.RANDALL G, LAGUNOFF M, ROIZMAN B. Herpes simplex virus 1 open reading frames O and P are not necessary for establishment of latent infection in mice. J Virol. 2000;74(19):9019–9027. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.9019-9027.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CHEN S H, LEE L Y. GARBER D A, et al. Neither LAT nor open reading frame P mutations increase expression of spliced or intron-containing ICP0 transcripts in mouse ganglia latently infected with herpes simplex virus. J Virol. 2002;76(10):4764–4772. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4764-4772.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.GALLOWAY D A, FENOGLIO C, SHEVCHUK M, et al. Detection of herpes simplex RNA in human sensory ganglia. Virology. 1979;95(1):265–268. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90429-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.STEVENS J G, WAGNER E K, DEVI-RAO G B, et al. RNA complementary to a herpesvirus alpha gene mRNA is prominent in latently infected neurons. Science. 1987;235(4792):1056–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.2434993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LANFRANCA M P, MOSTAFA H H, DAVIDO D J. HSV-1 ICP0: an E3 ubiquitin ligase that counteracts host intrinsic and innate immunity. Cells. 2014;3(2):438–454. doi: 10.3390/cells3020438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.JAVIER R T, STEVENS J G, DISSETTE V B, et al. A herpes simplex virus transcript abundant in latently infected neurons is dispensable for establishment of the latent state. Virology. 1988;166(1):254–257. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SEDARATI F, IZUMI K M, WAGNER E K, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcription plays no role in establishment or maintenance of a latent infection in murine sensory neurons. J Virol. 1989;63(10):4455–4458. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4455-4458.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.STEINER I, SPIVACK J G, LIRETTE R P, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcripts are evidently not essential for latent infection. EMBO J. 1989;8(2):505–511. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MADOR N, GOLDENBERG D, COHEN O, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcripts suppress viral replication and reduce immediate-early gene mRNA levels in a neuronal cell line. J Virol. 1998;72(6):5067–5075. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5067-5075.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.BURTON E A, HONG C S, GLORIOSO J C. The stable 2.0-kilobase intron of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript does not function as an antisense repressor of ICP0 in nonneuronal cells. J Virol. 2003;77(6):3516–3530. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3516-3530.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CHEN S H, KRAMER M F, SCHAFFER P A, et al. A viral function represses accumulation of transcripts from productive-cycle genes in mouse ganglia latently infected with herpes simplex virus. J Virol. 1997;71(8):5878–5884. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5878-5884.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.GARBER D A, SCHAFFER P A, KNIPE D M. A LAT-associated function reduces productive-cycle gene expression during acute infection of murine sensory neurons with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 1997;71(8):5885–5893. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5885-5893.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NICOLL M P, HANN W, SHIVKUMAR M, et al. The HSV-1 latency-associated transcript functions to repress latent phase lytic gene expression and suppress virus reactivation from latently infected neurons. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CLIFFE A R, GARBER D A, KNIPE D M. Transcription of the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript promotes the formation of facultative heterochromatin on lytic promoters. J Virol. 2009;83(16):8182–8190. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00712-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WANG Q Y, ZHOU C, JOHNSON K E, et al. Herpesviral latency-associated transcript gene promotes assembly of heterochromatin on viral lytic-gene promoters in latent infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(44):16055-16059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505850102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.GIORDANI N V, NEUMANN D M, KWIATKOWSKI D L, et al. During herpes simplex virus type 1 infection of rabbits, the ability to express the latency-associated transcript increases latent-phase transcription of lytic genes. J Virol. 2008;82(12):6056–6060. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02661-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LEIB D A, BOGARD C L, KOSZ-VNENCHAK M, et al. A deletion mutant of the latency-associated transcript of herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivates from the latent state with reduced frequency. J Virol. 1989;63(7):2893–2900. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.2893-2900.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.TROUSDALE M D, STEINER I, SPIVACK J G, et al. In vivo and in vitro reactivation impairment of a herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript variant in a rabbit eye model . J Virol. 1991;65(12):6989–6993. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6989-6993.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.BLOCK T M, DESHMANE S, MASONIS J, et al. An HSV LAT null mutant reactivates slowly from latent infection and makes small plaques on CV-1 monolayers. Virology. 1993;192(2):618–630. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.PERNG G C, DUNKEL E C, GEARY P A, et al. The latency-associated transcript gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is required for efficient in vivo spontaneous reactivation of HSV-1 from latency . J Virol. 1994;68(12):8045–8055. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8045-8055.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.PERNG G C, SLANINA S M, YUKHT A, et al. The latency-associated transcript gene enhances establishment of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency in rabbits. J Virol. 2000;74(4):1885–1891. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1885-1891.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.THOMPSON R L, SAWTELL N M. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript gene promotes neuronal survival. J Virol. 2001;75(14):6660–6675. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6660-6675.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.SAWTELL N M, POON D K, TANSKY C S, et al. The latent herpes simplex virus type 1 genome copy number in individual neurons is virus strain specific and correlates with reactivation. J Virol. 1998;72(7):5343–5350. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5343-5350.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.HOSHINO Y, PESNICAK L, STRAUS S E, et al. Impairment in reactivation of a latency associated transcript (LAT)-deficient HSV-2 is not solely dependent on the latent viral load or the number of CD8(+) T cells infiltrating the ganglia. Virology. 2009;387(1):193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'NEIL J E, LOUTSCH J M, AGUILAR J S, et al. Wide variations in herpes simplex virus type 1 inoculum dose and latency-associated transcript expression phenotype do not alter the establishment of latency in the rabbit eye model. J Virol. 2004;78(10):5038–5044. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5038-5044.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WATSON Z L, WASHINGTON S D, PHELAN D M, et al. In vivo knockdown of the herpes simplex virus 1 latency-associated transcript reduces reactivation from latency . J Virol. pii: 2018;92(16):00812–18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00812-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.PERNG G C, JONES C, CIACCI-ZANELLA J, et al. Virus-induced neuronal apoptosis blocked by the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript. Science. 2000;287(5457):1500–1503. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.PERNG G C, MAGUEN B, JIN L, et al. A gene capable of blocking apoptosis can substitute for the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript gene and restore wild-type reactivation levels. J Virol. 2002;76(3):1224–1235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1224-1235.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.THOMPSON R L, SAWTELL N M. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript gene promotes neuronal survival. J Virol. 2001;75(14):6660–6675. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6660-6675.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.HAMZA M A, HIGGINS D M, FELDMAN L T, et al. The latency-associated transcript of herpes simplex virus type 1 promotes survival and stimulates axonal regeneration in sympathetic and trigeminal neurons. J Neurovirol. 2007;13(1):56–66. doi: 10.1080/13550280601156297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.THOMPSON R L, SAWTELL N M. The herpes simplex virus type 1 latency associated transcript locus is required for the maintenance of reactivation competent latent infections. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(6):552–558. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0071-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.NICOLL M P, PROENÇA J T, CONNOR V, et al. Influence of herpes simplex virus 1 latency-associated transcripts on the establishment and maintenance of latency in the ROSA26R reporter mouse model. J Virol. 2012;86(16):8848–8858. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00652-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.CUI C, GRIFFITHS A, LI G, et al. Prediction and identification of herpes simplex virus 1-encoded microRNAs. J Virol. 2006;80(11):5499–5508. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00200-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.UMBACH J L, KRAMER M F, JURAK I, et al. MicroRNAs expressed by herpes simplex virus 1 during latent infection regulate viral mRNAs. Nature. 2008;454(7205):780–783. doi: 10.1038/nature07103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.JURAK I, KRAMER M F, MELLOR J C, et al. Numerous conserved and divergent microRNAs expressed by herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. J Virol. 2010;84(9):4659–4672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02725-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.TANG S, BERTKE A S, PATEL A, et al. An acutely and latently expressed herpes simplex virus 2 viral microRNA inhibits expression of ICP34.5, a viral neurovirulence factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(31):10931-10936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801845105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.TANG S, PATEL A, KRAUSE P R. Novel less-abundant viral microRNAs encoded by herpes simplex virus 2 latency-associated transcript and their roles in regulating ICP34.5 and ICP0 mRNAs. J Virol. 2009;83(3):1433–1442. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01723-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.KRAMER M F, JURAK I, PESOLA J M, et al. Herpes simplex virus 1 microRNAs expressed abundantly during latent infection are not essential for latency in mouse trigeminal ganglia. Virology. 2011;417(2):239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DU T, HAN Z, ZHOU G, et al. Patterns of accumulation of miRNAs encoded by herpes simplex virus during productive infection,latency, and on reactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(1) doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422657112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.JURAK I, HACKENBERG M, KIM J Y. et al. Expression of herpes simplex virus 1 microRNAs in cell culture models of quiescent and latent infection. J Virol. 2014;88(4):2337–2339. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03486-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.COKARIĆ B M, ZUBKOVIĆ A, FERENČIĆ A, et al. Herpes simplex virus 1 miRNA sequence variations in latently infected human trigeminal ganglia. Virus Res. 2018;256:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.PAN D, PESOLA J M, LI G, et al. Mutations inactivating herpes simplex virus 1 microRNA miR-H2 do not detectably increase ICP0 gene expression in infected cultured cells or mouse trigeminal ganglia. J Virol. pii: 2017;91(2):02001–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02001-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.FLORES O, NAKAYAMA S, WHISNANT A W, et al. Mutational inactivation of herpes simplex virus 1 microRNAs identifies viral mRNA targets and reveals phenotypic effects in culture. J Virol. 2013;87(12):6589–6603. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00504-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.JIANG X, BROWN D, OSORIO N, et al. A herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant disrupted for microRNA H2 with increased neurovirulence and rate of reactivation. J Neurovirol. 2015;21(2):199–209. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0319-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.SCHERER J, YAFFE Z A, VERSHININ M, et al. Dual-color herpesvirus capsids discriminate inoculum from progeny and reveal axonal transport dynamics. J Virol. 2016;90(21):9997–10006. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01122-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.AGGARWAL A, MIRANDA-SAKSENA M, BOADLE R A, et al. Ultrastructural visualization of individual tegument protein dissociation during entry of herpes simplex virus 1 into human and rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Virol. 2012;86(11):6123–6137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07016-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.HAFEZI W, LORENTZEN E U, EING B R, et al. Entry of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) into the distal axons of trigeminal neurons favors the onset of nonproductive, silent infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.SAWTELL N M, THOMPSON R L. De novo herpes simplex virus VP16 expression gates a dynamic programmatic transition and sets the latent/lytic balance during acute infection in trigeminal ganglia . PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.HAGMANN M, GEORGIEV O, SCHAFFNER W, et al. Transcription factors interacting with herpes simplex virus alpha gene promoters in sensory neurons. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(24):4978–4985. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.KOLB G, KRISTIE T M. Association of the cellular coactivator HCF-1 with the Golgi apparatus in sensory neurons. J Virol. 2008;82(19):9555–9563. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01174-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.LILLYCROP K A, DENT C L, WHEATLEY S C, et al. The octamer-binding protein Oct-2 represses HSV immediate-early genes in cell lines derived from latently infectable sensory neurons. Neuron. 1991;7(3):381–390. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90290-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.PROENÇA J T, COLEMAN H M, CONNOR V, et al. A historical analysis of herpes simplex virus promoter activation in vivo reveals distinct populations of latently infected neurones . J Gen Virol. 2008;89(12):2965–2974. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/005066-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.PROENÇA J T, COLEMAN H M, NICOLL M P, et al. An investigation of herpes simplex virus promoter activity compatible with latency establishment reveals VP16-independent activation of immediate-early promoters in sensory neurones. J Gen Virol. 2011;92(11):2575–2585. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.034728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.PAN D, FLORES O, UMBACH J L, et al. A neuron-specific host microRNA targets herpes simplex virus-1 ICP0 expression and promotes latency. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15(4):446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.SHU M, DU T, ZHOU G, et al. Role of activating transcription factor. in latent state in ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(39) doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515369112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MARGOLIS T P, IMAI Y, YANG L, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) establishes latent infection in a different population of ganglionic neurons than HSV-1: role of latency-associated transcripts. J Virol. 2007;81(4):1872–1878. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02110-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.BERTKE A S, SWANSON S M, CHEN J, et al. A5-positive primary sensory neurons are nonpermissive for productive infection with herpes simplex virus 1 in vitro . J Virol. 2011;85(13):6669–6677. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00204-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.IMAI Y, APAKUPAKUL K, KRAUSE P R, et al. Investigation of the mechanism by which herpes simplex virus type 1 LAT sequences modulate preferential establishment of latent infection in mouse trigeminal ganglia. J Virol. 2009;83(16):7873–7882. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00043-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DESHMANE S L, FRASER N W. During latency, herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA is associated with nucleosomes in a chromatin structure. J Virol. 1989;63(2):943–947. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.943-947.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.CLIFFE A R, COEN D M, KNIPE D M. Kinetics of facultative heterochromatin and polycomb group protein association with the herpes simplex viral genome during establishment of latent infection. MBio. pii. 2013;4(1):00590–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00590-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.KNIPE D M, CLIFFE A. Chromatin control of herpes simplex virus lytic and latent infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(3):211–221. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.KWIATKOWSKI D L, THOMPSON H W, BLOOM D C. The polycomb group protein Bmi1 binds to the herpes simplex virus 1 latent genome and maintains repressive histone marks during latency. J Virol. 2009;83(16):8173–8181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00686-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.BLOOM D C, GIORDANI N V, KWIATKOWSKI D L. Epigenetic regulation of latent HSV-1 gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799(3-4):246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.KUBAT N J, AMELIO A L, GIORDANI N V, et al. The herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) enhancer/rcr is hyperacetylated during latency independently of LAT transcription. J Virol. 2004;78(22):12508-12518. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12508-12518.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.KUBAT N J, TRAN R K, MCANANY P, et al. Specific histone tail modification and not DNA methylation is a determinant of herpes simplex virus type 1 latent gene expression. J Virol. 2004;78(3):1139–1149. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1139-1149.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.NEUMANN D M, BHATTACHARJEE P S, GIORDANI N V, et al. In vivo changes in the patterns of chromatin structure associated with the latent herpes simplex virus type 1 genome in mouse trigeminal ganglia can be detected at early times after butyrate treatment . J Virol. 2007;81(23):13248-13253. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01569-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.AMELIO A L, GIORDANI N V, KUBAT N J, et al. Deacetylation of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) enhancer and a decrease in LAT abundance precede an increase in ICP0 transcriptional permissiveness at early times postexplant. J Virol. 2006;80(4):2063–2068. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.2063-2068.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.KRISTIE T M, LIANG Y, VOGEL J L. Control of alpha-herpesvirus IE gene expression by HCF-1 coupled chromatin modification activities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799(3-4):257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.LEE J S. RAJA P, KNIPE D M. Herpesviral ICP0 protein promotes two waves of heterochromatin removal on an early viral promoter during lytic infection. MBio. pii: 2016;7(1):02007–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02007-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.RAJA P, LEE J S. PAN D, et al. A herpesviral lytic protein regulates the structure of latent viral chromatin. MBio. pii. 2016;7(3):00633–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00633-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.FERENCZY M W, DELUCA N A. Reversal of heterochromatic silencing of quiescent herpes simplex virus type 1 by ICP0. J Virol. 2011;85(7):3424–3435. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02263-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.LEE J S. RAJA P, PAN D, et al. CCCTC-binding factor acts as a heterochromatin barrier on herpes simplex viral latent chromatin and contributes to poised latent infection. MBio. pii. 2018;9(1):02372–17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02372-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.THEIL D, DERFUSS T, PARIPOVIC I, et al. Latent herpesvirus infection in human trigeminal ganglia causes chronic immune response. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(6):2179–2184. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63575-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.LIU T, TANG Q, HENDRICKS R L. Inflammatory infiltration of the trigeminal ganglion after herpes simplex virus type 1 corneal infection. J Virol. 1996;70(1):264–271. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.264-271.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.KNICKELBEIN J E, KHANNA K M, YEE M B. et al. Noncytotoxic lytic granule-mediated CD8 + T cell inhibition of HSV-1 reactivation from neuronal latency . Science. 2008;322(5899):268–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1164164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.KHANNA K M, BONNEAU R H, KINCHINGTON P R, et al. Herpes simplex virus-specific memory CD8 + T cells are selectively activated and retained in latently infected sensory ganglia . Immunity. 2003;18(5):593–603. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00112-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.ST L A J. PETERS B, SIDNEY J, et al. Defining the herpes simplex virus-specific CD8 + T cell repertoire in C57BL/6 mice . J Immunol. 2011;186(7):3927–3933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.FRANK G M, LEPISTO A J, FREEMAN M L, et al. Early CD4(+) T cell help prevents partial CD8(+) T cell exhaustion and promotes maintenance of herpes simplex virus 1 latency. J Immunol. 2010;184(1):277–286. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.LI L, LI Z, WANG E, et al. Herpes simplex virus 1 infection of tree shrews differs from that of mice in the severity of acute infection and viral transcription in the peripheral nervous system. J Virol. 2016;90(2):790–804. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02258-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.MARGOLIS T P, ELFMAN F L, LEIB D, et al. Spontaneous reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 in latently infected murine sensory ganglia. J Virol. 2007;81(20):11069-11074. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00243-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.MA J Z. RUSSELL T A, SPELMAN T, et al. Lytic gene expression is frequent in HSV-1 latent infection and correlates with the engagement of a cell-intrinsic transcriptional response. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.VELZEN M VAN, JING L, OSTERHAUS A D, et al. Local CD4 and CD8 T-cell reactivity to HSV-1antigens documents broad viral protein expression and immune competence in latently infected human trigeminal ganglia. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.RUSSELL T A, TSCHARKE D C. Lytic promoters express protein during herpes simplex virus latency. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(6):e1005729. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.KOSZ-VNENCHAK M, JACOBSON J, COEN D M, et al. Evidence for a novel regulatory pathway for herpes simplex virus gene expression in trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Virol. 1993;67(9):5383–5393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5383-5393.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.HALFORD W P, KEMP C D, ISLER J A, et al. ICP0, ICP4, or VP16 expressed from adenovirus vectors induces reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus type 1 in primary cultures of latently infected trigeminal ganglion cells. J Virol. 2001;75(13):6143–6153. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.6143-6153.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.HALFORD W P, SCHAFFER P A. ICP0 is required for efficient reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 from neuronal latency. J Virol. 2001;75(7):3240–3249. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3240-3249.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.CAI W, ASTOR T L, LIPTAK L M, et al. The herpes simplex virus type 1 regulatory protein ICP0 enhances virus replication during acute infection and reactivation from latency. J Virol. 1993;67(12):7501–7512. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7501-7512.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.THOMPSON R L, SAWTELL N M. Evidence that the herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0 protein does not initiate reactivation from latency in vivo . J Virol. 2006;80(22):10919-10930. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01253-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.SAWTELL N M, THOMPSON R L, HAAS R L. Herpes simplex virus DNA synthesis is not a decisive regulatory event in the initiation of lytic viral protein expression in neurons in vivo during primary infection or reactivation from latency . J Virol. 2006;80(1):38–50. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.38-50.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.THOMPSON R L, PRESTON C M, SAWTELL N M. De novo synthesis of VP16 coordinates the exit from HSV latency in vivo . PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.KIM J Y. MANDARINO A, CHAO M V, et al. Transient reversal of episome silencing precedes VP16-dependent transcription during reactivation of latent HSV-1 in neurons. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.WHITLOW Z, KRISTIE T M. Recruitment of the transcriptional coactivator HCF-1 to viral immediate-early promoters during initiation of reactivation from latency of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 2009;83(18):9591–9595. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01115-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.LIANG Y, VOGEL J L, NARAYANAN A, et al. Inhibition of the histone demethylase LSD1 blocks alpha-herpesvirus lytic replication and reactivation from latency. Nat Med. 2009;15(11):1312–1317. doi: 10.1038/nm.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.ALFONSO-DUNN R, TURNER A W, JEAN B P M, et al. Transcriptional elongation of HSV immediate early genes by the super elongation complex drives lytic infection and reactivation from latency. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21(4):507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.WILCOX C L, JOHNSON E M. Nerve growth factor deprivation results in the reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus in vitro . J Virol. 1987;61(7):2311–2315. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.7.2311-2315.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.CAMARENA V, KOBAYASHI M, KIM J Y. et al. Nature and duration of growth factor signaling through receptor tyrosine kinases regulates HSV-1 latency in neurons. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8(4):320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.WASHINGTON S D, EDENFIELD S I, LIEUX C, et al. Depletion of the insulator protein CTCF results in HSV-1 reactivation in vivo . J Virol. pii: 2018;92(11):00173–18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00173-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.NAGAMINE M, SHIMIZU Y. Effects of personal controls on cortisol secretion during stress processes. Shinrigaku Kenkyu. 2003;74(2):164–170. doi: 10.4992/jjpsy.74.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.DJORDJEVIĆ J, CVIJIĆ G, DAVIDOVIĆ V. Different activation of ACTH and corticosterone release in response to various stressors in rats. Physiol Res. 2003;52(1):67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.HUANG W, XIE P, XU M, et al. The influence of stress factors on the reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus type 1 in infected mice. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;61(1):115–122. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.BENMOHAMED L, OSORIO N, SRIVASTAVA R, et al. Decreased reactivation of a herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) latency-associated transcript (LAT) mutant using the in vivo mouse UV-B model of induced reactivation . J Neurovirol. 2015;21(5):508–517. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0348-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.SAINZ B, LOUTSCH J M, MARQUART M E, et al. Stress-associated immunomodulation and herpes simplex virus infections. Med Hypotheses. 2001;56(3):348–356. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2000.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.KOOK I, JONES C. The serum and glucocorticoid-regulated protein kinases (SGK) stimulate bovine herpesvirus 1 and herpes simplex virus 1 productive infection. Virus Res. 2016;222:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.SINANI D, CORDES E, WORKMAN A, et al. Stress-induced cellular transcription factors expressed in trigeminal ganglionic neurons stimulate the herpes simplex virus 1 ICP0 promoter. J Virol. 2013;87(23):13042-13047. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02476-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.CLIFFE A R, ARBUCKLE J H, VOGEL J L, et al. Neuronal stress pathway mediating a histone methyl/phospho switch is required for herpes simplex virus reactivation. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;18(6):649–658. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.WAGNER E K, BLOOM D C. Experimental investigation of herpes simplex virus latency. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10(3):419–443. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.BENMOHAMED L, OSORIO N, KHAN A A, et al. Prior corneal scarification and injection of immune serum are not required before ocular HSV-1 infection for UV-B-induced virus reactivation and recurrent herpetic corneal disease in latently infected mice. Curr Eye Res. 2016;41(6):747–756. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2015.1061024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.SAWTELL N M, THOMPSON R L. Rapid in vivo reactivation of herpes simplex virus in latently infected murine ganglionic neurons after transient hyperthermia . J Virol. 1992;66(4):2150–2156. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2150-2156.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.DASGUPTA G, BENMOHAMED L. Of mice and not humans: how reliable are animal models for evaluation of herpes CD8(+)-T cell-epitopes-based immunotherapeutic vaccine candidates? Vaccine. 2011;29(35):5824–5836. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.KWON B S, GANGAROSA L P, BURCH K D, et al. Induction of ocular herpes simplex virus shedding by iontophoresis of epinephrine into rabbit cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981;21(3):442–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.WEBRE J M, HILL J M, NOLAN N M, et al. Rabbit and mouse models of HSV-1 latency, reactivation, and recurrent eye diseases. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:612316. doi: 10.1155/2012/612316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.AL-DUJAILI L J, CLERKIN P P, CLEMENT C, et al. Ocular herpes simplex virus: how are latency, reactivation, recurrent disease and therapy interrelated? Future Microbiol. 2011;6(8):877–907. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.HILL J M, RAYFIELD M A, HARUTA Y. Strain specificity of spontaneous and adrenergically induced HSV-1 ocular reactivation in latently infected rabbits. Curr Eye Res. 1987;6(1):91–97. doi: 10.3109/02713688709020074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.PRESTON C M, MABBS R, NICHOLL M J. Construction and characterization of herpes simplex virus type 1 mutants with conditional defects in immediate early gene expression. Virology. 1997;229(1):228–239. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.MCMAHON R, WALSH D. Efficient quiescent infection of normal human diploid fibroblasts with wild-type herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 2008;82(20):10218-10230. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00859-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.DANAHER R J, JACOB R J, MILLER C S. Establishment of a quiescent herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in neurally-differentiated PC12 cells. J Neurovirol. 1999;5(3):258–267. doi: 10.3109/13550289909015812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.WILCOX C L, SMITH R L, FREED C R, et al. Nerve growth factor-dependence of herpes simplex virus latency in peripheral sympathetic and sensory neurons in vitro . J Neurosci. 1990;10(4):1268–1275. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01268.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.KATZENELL S, CABRERA J R, NORTH B J, et al. Isolation, purification, and culture of primary murine sensory neurons. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1656:229–251. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7237-1_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.CH'NG T H, ENQUIST L W. Neuron-to-cell spread of pseudorabies virus in a compartmented neuronal culture system. J Virol. 2005;79(17):10875-10889. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.10875-10889.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.KOYUNCU O O, MACGIBENY M A, HOGUE I B, et al. Compartmented neuronal cultures reveal two distinct mechanisms for alpha herpesvirus escape from genome silencing. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.KOYUNCU O O, SONG R, GRECO T M, et al. The number of alphaherpesvirus particles infecting axons and the axonal protein repertoire determines the outcome of neuronal infection. MBio. pii. 2015;6(2):00276–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00276-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.CAI G Y, PIZER L I, LEVIN M J. Fractionation of neurons and satellite cells from human sensory ganglia in order to study herpesvirus latency. J Virol Methods. 2002;104(1):21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(02)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]