Abstract

In a study assessing genetic diversity, 114 group A streptococcus (GAS) isolates were recovered from pediatric pharyngitis patients in Rome, Italy. These isolates comprised 22 different M protein gene (emm) sequence types, 14 of which were associated with a distinct serum opacity factor/fibronectin binding protein gene (sof) sequence type. Isolates with the same emm gene sequence type generally shared a highly conserved chromosomal macrorestriction profile. In three instances, isolates with dissimilar macrorestriction profiles had identical emm types; in each of these cases multilocus sequence typing revealed that isolates with the same emm type were clones having the same allelic profiles. Ninety-eight percent of the pharyngeal isolates had emm types previously found to be highly associated with mga locus gene patterns commonly found in pharyngeal GAS isolates.

Group A streptococci (GAS) are among the most prevalent pathogens afflicting humans, causing a wide diversity of human diseases. The M protein encoded by the emm gene is a major virulence factor and provides the basis for identifying about 80 different GAS serotypes, each of which is often associated with characteristic T-antigen patterns (12). GAS are also divisible into two broad groups based on the presence or absence of serum opacity factor (Sof) activity (10, 12). The inhibition of Sof activity with strain-specific antisera (anti-opacity factor typing) is another serologic tool that has been used for typing GAS for decades (14). Many strains are not precisely typeable by either M protein- or Sof protein-based serologic methods due to an array of technical problems (8). Most importantly, the majority of reference laboratories do not have the comprehensive set of typing sera necessary for this typing system.

A much simpler sequence-based means for typing GAS is completely compatible with the classical M and Sof protein-based serologic schemes (2). This system is based on sequencing the 5′ serotype-specific end of the M protein (emm) gene (15, 16) and hypervariable portions of the sof gene.

In the present study, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of chromosomal macrorestriction patterns was performed to assess the genetic relatedness among GAS isolates within different emm and sof sequence types. Multilocus sequence typing (13), recently developed for studying the population genetics of GAS (7), was used to demonstrate clonality in three instances where isolates had identical emm and sof sequences but had dissimilar PFGE patterns.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

Throat swab specimens were obtained from persons attending two general hospitals and one pediatric hospital in Rome, Italy. One hundred fourteen GAS isolates recovered between January and March 2000 were from 114 patients with pharyngitis. The majority of GAS isolates were recovered from the pediatric hospital (101 isolates). Of the 101 patients attending the pediatric hospital, 96 lived in the central area of Italy (94 in Rome and 2 in Latina) and 5 lived in the south of Italy (4 in Naples and 1 in Salerno). Thirteen isolates were from two general hospitals in Rome. The majority of GAS isolates (110) were recovered from individuals younger than 15 years, and 4 isolates were from adults older than 35. Sixty-four patients were male and 50 were female.

emm and sof amplicon restriction analysis.

emm gene PCR employed previously described primers 1 and 2 (16), while sof gene PCR fragments of about 550 to 650 bp were obtained through the use of primers sofF2 and sofR3 as previously described (2). emm gene amplicons were subjected to double digestion with HaeIII and HindII as previously described (1), and sof amplicons were subjected to DdeI digestion. Digests were analyzed by electrophoresis on 4% agarose gels (NUSIEVE 3:1) containing ethidium bromide.

emm and sof amplicon sequencing.

Sequence analysis of the 5′ regions of emm and sof gene amplicons was performed with primers emmseq2 and sofF, respectively (2). emm sequence typing and criteria defining emm and sof type designations have been previously described (1, 2). At least one amplicon for each emm and sof restriction fragment length polymorphism type shown in Table 1 was subjected to sequence analysis. Representative emm and/or sof amplicons were sequenced from each of PFGE types A to Y shown in Table 1. Three representative emm amplicons (and sof amplicons from sof+ isolates) from PFGE types A, C, E, F, and N were sequenced. Two representative emm amplicons (and sof amplicons from sof+ isolates) from PFGE types L, O, and S were sequenced. Cumulatively, a total of 41 emm amplicons and 29 sof gene amplicons were sequenced to generate the data in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Genotypic data from 114 pharyngeal GAS isolates from Rome, Italy

| No. of isolates | PFGE subtype | RFLPa result for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| emm | sof | emm/sof sequencesb | ||

| 14 | A1 | 1 | 1 | emm12/sof12 |

| 11 | A2 | 1 | 1 | emm12/sof12 |

| 1 | A3 | 1 | 1 | emm12/sof12 |

| 1 | A4 | 1 | 1 | emm12/sof12 |

| 1 | B1 | 1 | 1 | emm12/sof12 |

| 1 | Y1 | 27 | 6 | emm78/sof78 |

| 1 | C1 | 2 | 2 | emm89/sof89 |

| 4 | C2 | 2 | 2 | emm89/sof89 |

| 1 | C3 | 2 | 2 | emm89/sof89 |

| 1 | C4 | 2 | 2 | emm89/sof89 |

| 1 | C5 | 24 | 2 | emm89/sof89 |

| 2 | C6 | 2 | 2 | emm89/sof89 |

| 1 | C7 | 2 | 2 | emm89/sof89 |

| 1 | D1 | 2 | 2 | emm89/sof89 |

| 5 | E1 | 3 | 4 | emm4/sof4 |

| 1 | E2 | 3 | 4 | emm4/sof4 |

| 1 | E3 | 3 | 4 | emm4/sof4 |

| 1 | E4 | 3 | 4 | emm4/sof4 |

| 1 | E5 | 3 | 4 | emm4/sof4 |

| 1 | E6 | 3 | 4 | emm4/sof4 |

| 1 | E7 | 6 | 4 | emm4/sof4 |

| 3 | F1 | 15 | 14 | emm87/sof87 |

| 2 | F2 | 15 | 14 | emm87/sof87 |

| 1 | F3 | 14 | 14 | emm87/sof87 |

| 1 | F4 | 18 | 14 | emm87/sof87 |

| 1 | G1 | 19 | 5 | emm9/sof9/44 |

| 2 | H1 | 17 | Negc | emm3.1/Not applicable |

| 1 | H2 | 17 | Neg | emm3.1/Not applicable |

| 3 | I1 | 30 | Neg | emm5.3/Not applicable |

| 1 | I2 | 7 | Neg | emm5.3/Not applicable |

| 3 | J1a | 23 | 7 | emm28/sof28 |

| 1 | J2a | 23 | 7 | emm28/sof28 |

| 1 | K1a | 4 | 7 | emm28/sof28 |

| 1 | K2a | 4 | 7 | emm28/sof28 |

| 10 | L1 | 8 | Neg | emm1.7/Not applicable |

| 1 | L2 | 8 | Neg | emm1.7/Not applicable |

| 2 | M1 | 28 | 13 | emm75/sof75 |

| 3 | N1 | 20 | Neg | emm6/Not applicable |

| 1 | N1 | 21 | Neg | emm6/Not applicable |

| 1 | N2 | 9 | Neg | emm6/Not applicable |

| 2 | O1 | 5 | 8 | emm11/sof11 |

| 1 | O1 | 10 | 8 | emm11/sof11 |

| 1 | O2 | 5 | 8 | emm11/sof11 |

| 1 | P1 | 29 | 9 | st448/sof448 |

| 1 | Q1 | 11 | 10 | emm77/sof77 |

| 3 | Q2 | 11 | 10 | emm77/sof77 |

| 1 | R1 | 31 | 11 | emm59/sof59 |

| 1 | S1 | 12 | 3 | emm22/sof22 |

| 1 | S2 | 12 | 3 | emm22/sof22 |

| 1 | S3 | 12 | 3 | emm22/sof22 |

| 1 | T1 | 13 | Neg | emm80.1/Not applicable |

| 5 | U1 | 22 | Neg | emm29.1/Not applicable |

| 1 | V1 | 25 | Neg | emm14.2/Not applicable |

| 1 | W1 | 26 | 5 | emm44/61/sof9/44 |

| 2 | X1 | 16 | 12 | emm2/sof2 |

RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism.

All relevant emm and sof sequences, as well as GenBank accession numbers, are available at www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/infotech_hp.html.

Neg, sof PCR negative.

PFGE.

Isolates were subjected to chromosomal SmaI digestion and PFGE as previously described (2). Isolates differing by one to six bands from a given type (designated subtype 1 in this work) were assigned to that type as a subtype. Isolates differing by more than six bands represented distinct PFGE types.

Multilocus sequence typing.

Seven different GAS housekeeping gene fragment amplicons were generated, and 405- to 498-bp sequences were obtained using primers described by Enright et al. (7). For designating the multilocus sequence types (allelic profile or ST), the ST were matched with 1 of 100 different ST generated from an analysis of a large, highly diverse set of GAS isolates (7).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Twenty-six different PFGE types and 22 emm sequence types were found among the 114 GAS pharyngeal isolates genotyped (Table 1). There were no striking correlations of sequence types with sex (data not shown). The most prevalent emm type represented was emm12 with 28 isolates. emm12 and the other emm types represented by multiple isolates in this study are also well represented in population-based U.S. invasive isolates (1.6 to 20.7% of a recent population-based set of 2,612 isolates), with the exception of emm87 and emm29 (12 of 2,621 [<0.05%] and 1 of 2,612 [<0.004%] isolates, respectively) (see http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/infotech_hp.html).

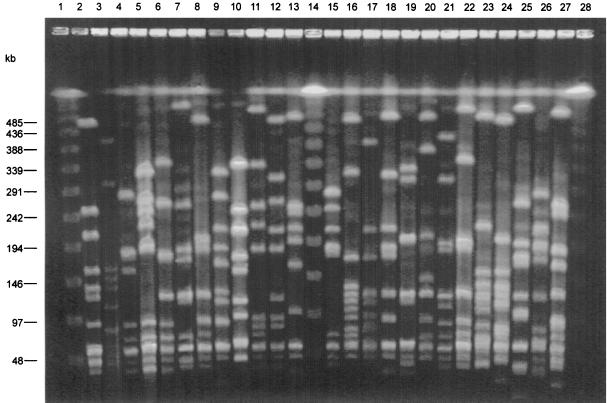

Only 3 of the 22 emm sequence types displayed more than one PFGE type. Although most emm types appear to represent genetically closely related sets of isolates that are geographically widely distributed (7), we have found several examples of isolates within the same emm sequence type that appear to be genetically distinct on the basis of a combination of dissimilarities among macrorestriction profiles, T-antigen types, and sof sequence types (2). In the present study, three emm types (emm12, emm89, and emm28) were each found to represent two different PFGE types (Table 1 and Fig. 1.). Nonetheless, all isolates were found to have multilocus allelic identity with the other isolates within their emm types (Table 2) using the recently developed multilocus sequence typing protocol for GAS (7). Each of the 20 alleles listed in Table 2 had been previously documented in this previous study (7). For each of the seven gene fragment targets, two to nine variable base positions were seen among the three allelic profiles (Table 2). Significantly, ST 36 and 52 represented the major allelic profiles previously found within temporally and geographically diverse sets of emm12 and emm28 isolates, respectively (7). While ST 101 had not been previously documented, six of the seven ST 101 alleles were found in previously examined emm89 isolates, and five of these represented the most common alleles found in emm89 isolates (7) (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Twenty-four PFGE types from representative GAS isolates. Lane 2, type A; lane 3, type B; lane 4, type C; lane 5, type D; lane 6, type E; lane 7, type F; lane 8, type G; lane 9, type H; lane 10, type I; lane 11, type J; lane 12, type K; lane 13, type L; lane 15, type M; lane 16, type N; lane 17, type O; lane 18, type P; lane 19, type Q; lane 20, type R; lanes 21 and 22, type S; lane 23, type T; lane 24, type U; lane 25, type V; lane 26, type W; lane 27, type X; lane 28, type Y; lanes 1, 14, and 28, lambda concatemer ladder (Bio-Rad).

TABLE 2.

Multilocus sequence typing results depicting clonal relationship between isolates with differing PFGE types but identical emm and sof sequence types

| PFGE types | emm/sof types | STa | Allele no. for:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gki | gtr | murI | mutS | recP | xpt | yqiL | |||

| A1, B1 | emm12/sof12 | 36 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| C2, C3, D1 | emm89/sof89 | 101 | 16 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 3 |

| J1, J2, K1, K2 | emm28/sof28 | 52 | 11 | 6 | 14 | 5 | 9 | 17 | 19 |

Multilocus ST based on the indicated seven housekeeping gene fragment sequences (7).

In addition, these isolates with the same emm type but different PFGE types had sequence identity within 550- to 650-bp 5′ sof gene fragments. All other sof-positive isolates, representing 19 distinct emm types, had 5′ sof gene sequences previously found to be highly associated with their emm types (2). The data shown in Tables 1 and 2 demonstrate the high genetic relatedness among individual emm type isolates of this study.

We found very little emm sequence variation within emm and sof 5′ sequences (see www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/infotech_hp.html for relevant sequences, references, and sequence type strains). Only types emm5.3, emm1.7, emm80.1, emm29.1, and emm14.2 contained one to three single-base changes, compared to the sequences of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) emm type reference strains, within bases encoding the N-terminal mature 50 amino acids. Each base change relative to the sequence of the emm type reference strain (i.e., for emm1, emm5, emm14, emm29, and emm80) resulted in an amino acid substitution, and, except for emm5.3, at least one nonconservative amino acid substitution relative to the closest matching CDC database emm allele was observed. For example, emm1.7 was found in the single PFGE subtype L2 isolate and contained a single base change compared to emm1, resulting in the nonconservative Glu-to-Val change at mature M1 residue 8. The emm5.3 allele differs only by a conservative change in codon 7 from emm5.8193. The cumulative PFGE- and sequence-based results (ST, emm, and sof) presented in this study (Tables 1 and 2) are in agreement with data that document genotypic stability within a broad array of individual clones existing within this species (7).

Seven of the 26 PFGE types (30 of 114 isolates) comprised sof PCR-negative isolates, which is consistent with these specific emm types being commonly associated with the opacity factor-negative phenotype and an apparent lack of the sof gene (2). Nineteen PFGE types comprised sof-positive isolates, accounting for 84 isolates. It is notable that 28 of these 84 isolates were emm12 isolates, which are invariably opacity factor negative (12). To date, emm12 represents the only known emm type commonly associated with emm/emm-like gene patterns A to C and the presence of a sof gene.

The emm and emm-like genes that lie at the mga locus have five different patterns, determined by their peptidoglycan-spanning domain-encoding sequences and relative arrangements (11). The genetic marker of patterns A to C is primarily associated with the pharyngeal GAS reservoir, pattern D is primarily associated with the impetigo reservoir, and pattern E strains commonly occur at both pharyngeal and skin sites (3, 4). The vast majority of isolates having the same emm type also have the same emm/emm-like gene pattern (5). If these same associations between emm type and patterns A to E are found in these isolates, the data shown in Table 1 are consistent with the previously determined pattern associations. Of the 22 emm types found among these 114 pharyngeal isolates (Table 1), types 1, 3, 5, 6, 12, 14, and 29, representing 50% of the total isolates, are typically associated with patterns A to C. emm types 2, 4, 9, 11, 22, 28, 44/61, 59, 75, 77, 78, 87, and 89, accounting for 48% of the isolates, are typically associated with pattern E. Of all the emm types found in these 114 pharyngeal isolates, only emm80 (accounting for a single isolate) has been associated with emm/emm-like gene pattern D (9). The pattern of emm and emm-like genes at the mga locus of emm sequence type st448 isolates has not been determined. These results are consistent with previous findings strongly tying patterns A to C or pattern E to strains found in the upper respiratory tract, whereas pattern D strains have a weak association with the pharyngeal reservoir (3, 5).

Two pecularities of the emm and sof sequence-based typing system relevant to the data presented in Table 1 should be explained. First, 5′ sof sequence type sof9/44 is found in both emm9 isolates and in a subset of emm44/61 isolates (2). Although sof9 and sof44 are identical within sequences encoding the mature Sof N-terminal 343 residues (and the 5′ sequence obtained in this study), the deduced proteins diverge over the remaining two-thirds of their respective enzymatic domains. Second, the emm44 and emm61 genes have apparently identical sequences, and recent evidence demonstrates that M type 44 and M type 61 reference strains have identical M serotypes (2; unpublished information). However, the classical M type 44 and M type 61 reference strains are distinguishable through characteristic T-antigen patterns, anti-opacity factor types, and sof gene sequence types (2, 12). The sof9/44 sequence found in the single emm44/61 isolate indicates that this isolate is probably highly related to the M type 44 reference strain, which also has the sof9/44 sequence type (2). In CDC population-based surveillance we encounter roughly equivalent numbers of “M61-like” isolates and “M44-like” isolates (see www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/infotech_hp.html).

Epidemiologic study of GAS isolates has been primarily based on M serotyping for decades. At the present time, a system predictive of the M serotype is still possibly the most useful, since it appears to relate fairly accurately past and current findings for individual GAS clones. emm sequence-based methods of population-based subtyping will conceivably be used in the near future to formulate multi-M type-specific GAS vaccines (6). This study represents the first genotypic survey of GAS isolates recovered in the south-central area of Italy. Pharyngeal strains are likely to represent the major GAS reservoir for invasive and noninvasive diseases in Italy and in other temperate countries. For example, in a study of 64 sterile-site GAS isolates from Connecticut, only 1 pattern D isolate was encountered (9). Vaccines targeting multiple emm types represented by predominant pharyngeal isolates could possibly be used in the future to drastically decrease all GAS-mediated diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Zhongya Li and Varja Sakota for their excellent technical work in the CDC streptococcal genetics laboratory. We thank M. Cava from the Hospital “San Filippo Neri” for providing some pharyngeal GAS strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beall B, Facklam R, Elliott J A, Franklin A R, Hoenes T, Jackson D, Laclaire L, Thompson T, Viswanathan R. Streptococcal emm types associated with T agglutination patterns and the use of conserved emm gene restriction fragment patterns for subtyping group A streptococci. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:893–898. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-10-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beall B, Gherardi G, Lovgren M, Forwick B A, Facklam R R, Tyrrell G J. emm and sof gene sequence variation in relation to serological typing of opacity factor positive group A streptococci. Microbiology. 2000;146:1195–1209. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-5-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bessen D E, Sotir C M, Readdy T L, Hollingshead S K. Genetic correlates of throat and skin isolates of group A streptococci. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:896–900. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bessen D E, Izzo M, Fiorentino T, Caringal R, Hollingshead S K, Beall B. Genetic linkage of exotoxin alleles and emm gene markers for tissue tropism in group A streptococci. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:627–636. doi: 10.1086/314631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bessen D E, Carapetis J R, Beall B, Katz R, Hibble M, Currie B J, Collingridge T, Izzo M W, Scaramuzzino D A, Sriprakash K S. Contrasting molecular epidemiology of group A streptococci causing tropical and nontropical infections of the skin and throat. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1109–1116. doi: 10.1086/315842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dale J B, Simmons M, Chiang E C, Chiang E Y. Recombinant, octavalent group A streptococcal M protein vaccine. Vaccine. 1996;14:944–948. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(96)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enright M C, Spratt B G, Kalia A, Cross J H, Bessen D E. Multilocus sequence typing of Streptococcus pyogenes and the relationships between emm type and clone. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2416–2427. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2416-2427.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Facklam R, Beall B, Efstratiou A, Fischetti V, Johnson D, Kaplan E, Kriz P, Lovgren M, Martin D, Schwartz B, Totolian A, Bessen D, Hollingshead S, Rubin F, Scott J, Tyrrell G. Demonstration of emm typing and validation of provisional M types for group A streptococci. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:247–253. doi: 10.3201/eid0502.990209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiorentino T R, Beall B, Mshar P, Bessen D E. A genetic-based evaluation of the principal tissue reservoir for group A streptococci isolated from normally sterile sites. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:177–182. doi: 10.1086/514020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gooder H. Association of a serum opacity reaction with serological type in Streptococcus pyogenes. J Gen Microbiol. 1961;25:347–352. doi: 10.1099/00221287-25-3-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollingshead S K, Readdy T L, Yung D L, Bessen D E. Structural heterogeneity of the emm gene cluster in group A streptococci. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:707–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson D R, Kaplan E L. A review of the correlation of T-agglutination patterns and M-protein typing and opacity factor production in the identification of group A streptococci. J Med Microbiol. 1993;38:311–315. doi: 10.1099/00222615-38-5-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maiden M C, Bygraves J A, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell J E, Urwin R, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zurth K, Caught D A, Feavers I M, Achtman M, Spratt B G. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maxted W R, Widdowson J P M, Fraser C A, Ball L, Bassett D C J. The use of the serum opacity reaction in the typing of group A streptococci. J Med Microbiol. 1973;6:83–90. doi: 10.1099/00222615-6-1-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Podbielski A, Melzer B, Lutticken R. Application of the polymerase chain reaction to study the protein(-like) gene family in beta-hemolytic streptococci. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1991;180:213–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00215250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whatmore A M, Kapur V, Sullivan D J, Musser J M, Kehoe M A. Non-congruent relationships between variation in emm gene sequences and the population genetic structure of group A streptococci. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:619–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]