Abstract

Fifty-nine isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis obtained from different states in the United States and representing 25 interstate clusters were investigated. These clusters were identified by computer-assisted analysis of DNA fingerprints submitted during 1996 and 1997 by different laboratories participating in the CDC National Genotyping and Surveillance Network. Isolates were fingerprinted with the IS6110 right-hand probe (IS6110-3′), the IS6110 left-hand probe (IS6110-5′), and the probe pTBN12, containing the polymorphic GC-rich sequence (PGRS). Spoligotyping based on the polymorphism in the 36-bp direct-repeat locus was also performed. As a control, 43 M. tuberculosis isolates in 17 clusters obtained from patients in Arkansas during the study period were analyzed. Of the 25 interstate clusters, 19 were confirmed as correctly clustered when all the isolates were analyzed on the same gel using the IS6110-3′ probe. Of the 19 true IS6110-3′ clusters, 10 (53%) were subdivided by one or more secondary typing methods. Clustering of the control group was virtually identical by all methods. Of the three different secondary typing methods, spoligotyping was the least discriminating. IS6110-5′ fingerprinting was as discriminating as PGRS fingerprinting. The data indicate that the IS6110-5′ probe not only is a useful secondary typing method but also probably would prove to be a more useful primary typing method for a genotyping network which involves isolates from different geographic regions.

A thorough understanding of tuberculosis (TB) transmission and pathogenesis is fundamental for the development of a rational approach to disease control. The development of genotyping methods based on various genetic markers on the chromosome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the establishment of an internationally standardized method of DNA fingerprinting using insertion sequence IS6110 as a probe have increased our ability to accurately differentiate strains of M. tuberculosis (8, 26, 29). The identification of related isolates of M. tuberculosis enables one to distinguish specific strains, providing a background in which to determine the characteristics of strains and their transmission in communities (1, 2, 13, 23, 31, 33). Increased application of DNA fingerprinting has advanced our understanding of the dynamics of TB epidemiology. DNA fingerprinting has proven useful for investigating nosocomial and institutional transmission (11, 12, 20), investigating outbreaks (11, 12, 20), confirming instances of laboratory cross-contamination (5, 6, 22), differentiating relapse caused by endogenous reactivation from reinfection by an exogenous strain (24, 27), and studying TB transmission in large populations (2–4, 7, 10, 16, 23, 28, 31).

The most widely utilized method of DNA fingerprinting uses the insertion sequence IS6110 to visualize DNA restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) of M. tuberculosis (26). In the United States and Europe, networks have been developed to establish IS6110 DNA fingerprint databases. Organized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the tuberculosis Genotyping and Surveillance Network, which includes seven regional genotyping laboratories and seven tuberculosis sentinel surveillance sites, was initiated in 1996. Subsequently, a national database was generated which consists of IS6110 DNA fingerprints of M. tuberculosis isolated from patients residing in different geographic areas of the United States and epidemiologic information about the patients from whom these isolates were obtained. Although there was remarkable diversity in the IS6110 fingerprints in the national database, some isolates obtained from pateints residing in different states had identical fingerprints (cross-state matched fingerprints). The existence of cross-state matched fingerprints raises the question of whether these interstate clusters represent widespread distribution of certain strains or transmission of tuberculosis among residents of different states. That is, does a common IS6110 DNA fingerprint identified among isolates from different geographic regions always indicate that these isolates are clonally related or epidemiologically linked? The frequency at which the matching IS6110 fingerprints indicate genetic and/or epidemiologic relatedness remains largely unknown. The present study was conducted in order to address these issues at the laboratory level. Isolates of M. tuberculosis obtained from different states in the United States representing 25 interstate fingerprint clusters found in the national database during 1996 and 1997 were typed with a series of genotyping methods. These methods included IS6110 fingerprinting using probes directed towards the right side (IS6110-3′) and the left side (IS6110-5′) of the PvuII site within the insertion sequence, pTBN12 fingerprinting based on the polymorphic GC-rich sequence (PGRS), and spoligotyping based on the analysis of polymorphism in the direct-repeat (DR) locus (8, 9, 15, 17, 21, 26). Among these methods, IS6110-3′ fingerprinting is the recommended standard genotyping method and has been routinely used worldwide (26).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

M. tuberculosis isolates.

Fifty-nine isolates of M. tuberculosis included in this study were obtained from Arkansas, Texas, Massachusetts, California, Maryland, Michigan, and New Jersey. The isolates were selected on the basis that they contained more than five copies of IS6110 and their fingerprint patterns matched that of at least one patient from Arkansas. The sample represents 25 interstate fingerprint clusters found in the national database during 1996 and 1997 based on matching IS6110-3′ fingerprints submitted by different regional genotyping laboratories. The interstate fingerprint clusters included 1 to 30 isolates from each state (Table 1). When there was more than one isolate from a state that was part of an interstate cluster, one isolate from that cluster in each state was randomly selected. As a control, 43 M. tuberculosis isolates with more than five copies of IS6110 that were in 17 clusters found in Arkansas during the study period (1996 to 1997) were analyzed with the same methods. These 17 clusters represent all high-copy-number clusters in Arkansas during the study period.

TABLE 1.

Origin and secondary typing of 25 interstate clusters identified by image analysis of IS6110-3′ RFLP patterns

| Cluster no. | IS6110 copy no. | Origin (no. of isolates) | No. of isolates analyzedb | Matched by fingerprinting methoda

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS6110-3′ | IS6110-5′ | PGRS | Spoligotyping | ||||

| 1 | 6 | Arkansas (2), Michigan (1) | 2 | Y | Y | N | Y |

| 2 | 8 | Arkansas (1), Michigan (2) | 2 | N | N | N | N |

| 3 | 9 | Arkansas (1), California (2) | 2 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 4 | 9 | Arkansas (1), Massachusetts (2) | 2 | Y | N | N | NAc |

| 5 | 10 | Arkansas (1), Michigan (1) | 2 | Y | N | N | N |

| 6 | 10 | Arkansas (1), Texas (1) | 2 | N | N | N | Y |

| 7 | 10 | Arkansas (4), Massachusetts (1), Texas (11) | 3 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 8 | 10 | Arkansas (1), Michigan (2), Maryland (1) | 3 | Y | Y (2), N (1) | Y (2), N (1) | Y |

| 9 | 11 | Arkansas (1), Maryland (1) | 2 | N | N | N | N |

| 10 | 11 | Arkansas (1), Maryland (1) | 2 | Y | Y | Y | N |

| 11 | 11 | Arkansas (1), Michigan (1) | 2 | Y | N | N | Y |

| 12 | 11 | Arkansas (1), Michigan (1), California (1) | 3 | Y (2), N (1) | N | Y | Y |

| 13 | 11 | Arkansas (3), New Jersey (1) | 2 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 14 | 12 | Arkansas (2), Texas (1) | 2 | Y | N | Y | Y |

| 15 | 12 | Arkansas (2), Massachusetts (1), New York (5), California (2) | 4 | Y | Y (3), N (1) | N | Y (3), N (1) |

| 16 | 12 | Arkansas (7), Texas (3) | 2 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 17 | 12 | Arkansas (2), Michigan (1), California (4) | 3 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 18 | 12 | Arkansas (1), Maryland (1), Massachusetts (1) | 3 | Y (2), N (1) | Y (2), N (1) | Y (2), N (1) | Y |

| 19 | 12 | Arkansas (1), Texas (2) | 2 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 20 | 13 | Arkansas (1), Michigan (1) | 2 | N | N | N | Y |

| 21 | 13 | Arkansas (3), Texas (4), California (1) | 3 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 22 | 13 | Arkansas (2), California (1) | 2 | N | N | N | Y |

| 23 | 13 | Arkansas (1), California (6) | 2 | Y | Y | N | Y |

| 24 | 16 | Arkansas (1), Texas (7) | 2 | N | N | Y | Y |

| 25 | 21 | Arkansas (5), Texas (30), Maryland (1) | 3 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Y, yes; N, no. Numbers in parentheses represent numbers of isolates.

One isolate from each state was analyzed.

NA, DNA from this cluster was not available for spoligotyping.

Genotyping with different genetic markers.

Isolates of M. tuberculosis were cultured on Lowenstein-Jensen medium. Chromosomal DNA was extracted from the isolates with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol as described previously (19). Restriction endonuclease PvuII (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) was used to cleave DNA for IS6110 DNA fingerprinting.

The isolates included in this study were identified as belonging to the same interstate or intrastate cluster on the basis of computer-assisted analysis of IS6110-3′ RFLP using Whole Band Analyzer software. (version 3.4; Bioimage, Ann Arbor, Mich.). DNA samples of all the isolates within individual clusters were electrophoresed in adjacent lanes of the same gel; blots containing the PvuII restriction fragments were first hybridized with the IS6110-3′ probe as a reliability test of computer matching of fingerprints generated by different genotyping laboratories. The IS6110-3′ probe in this study is a PCR product complementary to the sequence on the right side of the PvuII site within IS6110, extending from bp 568 to 1089 (25). The same blots were rehybridized with the IS6110-5′ probe, which is a PCR product complementary to the sequence on the left side of the PvuII site within IS6110, extending from bp 36 to 171 (25). For pTBN12 fingerprinting, DNA was restricted with AluI (Promega Corp.,). The PGRS probe, designated pTBN12, is a 3.4-kb insert of a polymorphic GC-rich repetitive sequence contained in the recombinant plasmid pTBN12. Preparation of the probes was the same as described previously (33). Fingerprinting experiments were performed essentially according to standard procedures as described previously (9, 26). The probes were labeled by use of the enhanced chemiluminescence direct nucleic acid labeling system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England). Spoligotyping to detect 43 known spacer sequences that intersperse the DRs in the genomic DR locus of M. tuberculosis complex strains was performed as described previously (17).

Analysis of genotyping results.

Electrophoresis of isolates clustered by computerized RFLP analysis in adjacent lanes of gels enables the RFLP patterns to be compared by visual inspection. In making comparisons, two or three different exposures of the same blot were used to distinguish bands that were possibly doublets. IS6110 fingerprints were considered to be identical if they contained an equal number of IS6110-hybridizing fragments of identical size. RFLP patterns generated by PGRS fingerprinting were also compared by visual inspection. Bands that were larger than 1.6 kbp were taken into consideration in the comparison. Patterns consisting of equal numbers of bands of identical sizes and intensities were read as matches. Spoligotyping results were expressed as the presence (by using letter O) or absence (by using a dot) of each of the 43 spacer sequences based on visual inspection. The spoligotyping data were entered in Microsoft Excel software and sorted according to the similarity of the patterns. Spoligotypes that contained the same spacers were considered to be identical.

RESULTS

IS6110 RFLP patterns.

Based on the IS6110-3′ fingerprinting, 12 isolates constituting 6 of the 25 interstate clusters were no longer clustered. Two isolates, which belonged to two other clusters that contained isolates from more than two states, were found to be different from other isolates in their original clusters. Thus, a total of 14 (24%) of the 59 isolates examined were differentiated by IS6110-3′ fingerprinting. The differences found among isolates in an interstate cluster were changes in the size of one or two hybridizing fragments and the addition or deletion of one or two hybridizing fragments. In contrast to the interstate clusters, all 43 isolates in the 17 intrastate clusters from Arkansas were confirmed to be in their original clusters when analyzed on the same gel.

Based on the results of IS6110-5′ fingerprinting, 11 of the 25 interstate clusters were found to be comprised of isolates with different patterns, and 3 other clusters were subdivided. This resulted in a total of 26 (44%) of the 59 isolates sampled from the interstate clusters being differentiated. Nevertheless, none of the 17 intrastate clusters from Arkansas were subdivided by the IS6110-5′ RFLP.

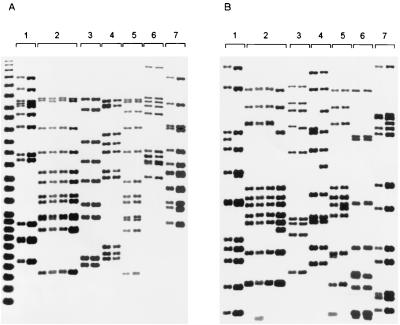

The differentiating value of the IS6110-5′ probe as a secondary typing method was tested on the 19 interstate clusters comprised of isolates that were confirmed to be identical with the IS6110-3′ probe when electrophoresed on the same gel. Isolates in 5 of the 19 clusters were discriminated on the basis of a unique IS6110-5′ fingerprint. Two clusters involving three states were subdivided. The differences found among the IS6110-3′ clustered isolates when probed with the IS6110-5′ secondary typing included changes in size of the fragments and/or addition or deletion of fragments (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Polymorphism of IS6110-5′ RFLP patterns found between or among isolates in seven IS6110-3′-based interstate clusters. Shown are fingerprints of M. tuberculosis isolates generated by IS6110-3′ (A) and IS6110-5′ (B) fingerprinting. Brackets indicate clusters identified by IS6110-3′ fingerprinting: 1, cluster 14; 2, cluster 15; 3, cluster 4; 4, cluster 5; 5, cluster 11; 6, cluster 8; 7, cluster 12.

PGRS fingerprinting.

PGRS fingerprinting using the pTBN12 probe showed that 11 of the 25 interstate clusters were comprised of isolates with different patterns, and 2 clusters were subdivided. The total number of isolates among the 59 isolates related to the interstate clusters that were identified to be different by PGRS fingerprinting was 26, accounting for 44% of the isolates analyzed. Of the 19 IS6110-3′ interstate clusters confirmed on the same gel, 6 (32%) were found to contain isolates that were differentiated by the PGRS secondary typing and 1 was subdivided. All of the 43 isolates in the 17 intrastate clusters remained in the same clusters after being typed with pTBN12.

Spoligotyping.

Spoligotyping was carried out on 24 of the 25 interstate clusters. One cluster was not spoligotyped due to the fact that DNA was not available. Of the 24 clusters that were spoligotyped, 4 (17%) were found to consist of isolates with different spoligotypes and a fifth cluster was subdivided. Thus, only 9 (16%) of the 57 isolates analyzed from interstate clusters were differentiated by spoligotyping.

Isolates in 2 of the 19 interstate clusters confirmed by IS6110-3′ fingerprinting were discriminated by spoligotyping. Spoligotyping of 43 isolates in intrastate clusters from Arkansas differentiated isolates in only 1 of the 17 intrastate clusters.

Correlation among different typing methods.

Of the 25 interstate clusters, 9 (36%), including 22 isolates, were confirmed by all four typing methods; 10 were confirmed to be true clusters by IS6110-3′ fingerprinting but were divided by one or more secondary typing methods (Table 1). Among these 10 clusters, 1 was divided by all three secondary typing methods, 3 were divided by IS6110-5′ and PGRS fingerprinting, 2 were divided by IS6110-5′ fingerprinting, 3 were divided by PGRS fingerprinting, and 1 was divided by spoligotyping.

Isolates in five of the remaining six interstate clusters were differentiated by IS6110-3′, IS6110-5′, and PGRS fingerprinting. However, only two of these five clusters were divided by spoligotyping (Table 1). Isolates in the last interstate cluster were discriminated by IS6110-3′ and IS6110-5′ fingerprinting, but not by PGRS fingerprinting or spoligotyping.

Among the 17 intrastate clusters from Arkansas, 16 (94%) were proven by all four methods. For the other cluster, discrepant results were found between spoligotyping and the other three methods.

DISCUSSION

While DNA fingerprinting of M. tuberculosis isolates is being used increasingly in epidemiologic studies, the interpretation of fingerprint data is becoming increasingly complex, depending on the setting of the studies and the particular methods used for fingerprinting (4, 14). The present study was the first to investigate the implication of IS6110 clustering resulting from computerized RFLP analyses of isolates obtained from different geographic regions. This report provides an assessment of the standardized IS6110 fingerprinting method relative to other secondary fingerprinting methods and sets out information useful for studying the long-term clonal expansion and tracing of M. tuberculosis transmission in different settings, e.g., in a given geographic region and across geographic regions.

The establishment of an internationally standardized methodology for DNA fingerprinting of M. tuberculosis permits the analysis and comparison of DNA fingerprint patterns produced in many different laboratories (18). However, since almost a quarter of the interstate clusters were subdivided when the isolates were run on the same gel, concerns have been raised regarding the possibility of overestimating the number of interregional (or interstate in the present case) clusters in a genotyping network that pools results generated from different typing laboratories.

It is well established that traditional DNA fingerprinting using IS6110-3′ as a probe is not sensitive in differentiating among M. tuberculosis isolates that harbor fewer than five copies of IS6110 (7, 9, 30). In most studies, isolates that have identical IS6110 fingerprints and more than five copies have been considered to be from the same strain (2, 4, 7). However, it has been previously reported that approximately one-quarter of the high-copy-number isolates from patients in different geographic regions clustered by IS6110-3′ can be differentiated by pTBN12 secondary typing (31). In the present study, 53% (10 of 19) of the IS6110-3′ interstate clusters that were confirmed by a reliability test were subdivided by IS6110-5′ or pTBN12 secondary fingerprinting. These findings confirm and extend previous observations regarding fingerprint diversity among IS6110-3′ clustered high-copy-number isolates from different geographic regions. The results further demonstrate the importance of secondary typing for investigating the relatedness of clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis obtained from widely separated geographic regions. The findings on the intrastate clusters demonstrate the reliability of IS6110-3′ RFLP analysis for evaluating isolates from the same geographic region.

The limitation of the study is that we sampled only one isolate from each state involved in the interstate clusters. However, this is consistent with the practice of the CDC national fingerprint database in which the IS6110 RFLP pattern of a single isolate from a cluster identified by the submitting laboratory is submitted to represent the fingerprint of the isolates in the cluster. Moreover, the data obtained from the control group, 17 intrastate clusters from Arkansas, suggest that the selected isolates are indeed identical to the other isolates in the same clusters since little or no variation was found among isolates in the 17 intrastate clusters.

Of the three different secondary typing methods used in this study, spoligotyping was the least discriminating. IS6110-5′ secondary fingerprinting was as differentiating as the commonly used PGRS secondary typing. IS6110-5′ secondary typing requires less time than the PGRS secondary typing method and can be accomplished on the same blot as that used for IS6110-3′ fingerprinting. In addition, the fingerprint patterns generated by IS6110-5′ are easier to read and interpret than those obtained by PGRS fingerprinting. Finally, the simplicity of IS6110-5′ fingerprint patterns will facilitate computer-assisted analysis. Therefore, IS6110-5′ fingerprinting is a useful secondary method for typing M. tuberculosis isolates.

Since a matching fingerprint pattern generated by the IS6110-3′ probe does not always indicate that IS6110 is inserted in the same site, probing with both IS6110-3′ and IS6110-5′ probes and getting identical fingerprint patterns with both probes should increase the likelihood of isolates being clonally related. For the 59 isolates obtained from different states, the commonly used IS6110-3′ probe detected only half of the unique isolates that were identified by the IS6110-5′ probe. This observation suggests that a combination of IS6110-3′ and IS6110-5′ fingerprinting will increase the reliability of IS6110 fingerprinting in studying the clonal relationship of M. tuberculosis isolates and that IS6110-5′ fingerprinting might serve as a more appropriate primary typing method for a genotyping network that compares isolates from different geographic regions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by the CDC, National Tuberculosis Genotyping and Surveillance Network cooperative agreement.

The Regional Tuberculosis Genotyping Laboratories at Alabama, California, Michigan, Texas, and New York and the Public Health Research Institute, New York, N.Y., are acknowledged for providing isolates and information. We are indebted to Michael Freeland, Bill Starrett, and Don Cunningham for their excellent technical assistance in laboratory work during the study and to Jack Crawford and Chris Braden at the CDC for their valuable comments given in the process of the manuscript's preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alland D, Kalkut G E, Moss A R, McAdam R A, Hahn J A, Bosworth W, Ducker E, Bloom B R. Transmission of tuberculosis in New York City, an analysis by DNA fingerprinting and conventional epidemiologic methods. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1710–1716. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406163302403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes P F, Yang Z H, Preston-Martin S, Pogoda J M, Jones B E, Otaya M, Eisenach K D, Knowles L, Harvey S, Cave M D. Patterns of tuberculosis transmission in Central Los Angeles. JAMA. 1997;278:1159–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer J, Yang Z, Poulsen S, Andersen Å. Results from 5 years of nationwide DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates in a country with a low incidence of M. tuberculosis infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:305–308. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.305-308.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braden C R, Templeton G L, Cave M D, Valway S, Onorato I M, Castro K G, Moers D, Yang Z H, Stead W W, Bates J H. Interpretation of restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from a state with a large rural population. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1446–1452. doi: 10.1086/516478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braden C R, Templeton G L, Stead W W, Bates J H, Cave M D, Valway S E. Retrospective identification of laboratory cross-contamination of M. tuberculosis cultures with use of DNA fingerprint analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:35–40. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burman W J, Stone B L, Reves R R, Wilson M L, Yang Z H, El-Hajj H, Bates J H, Cave M D. The incidence of false-positive cultures for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:321–326. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burman W J, Reves R R, Hawkes A P, Rietmeijer C A, Yang Z H, El-Hajj H, Bates J H, Cave M D. DNA fingerprinting with two probes decreases clustering of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1140–1146. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.3.9117000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cave M D, Eisenach K D, McDermott P F, Bates J H, Crawford J T. IS6110: conservation of sequence in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and its utilization in DNA fingerprinting. Mol Cell Probes. 1991;5:73–80. doi: 10.1016/0890-8508(91)90040-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaves F, Yang Z, El Hajj H, Alonso M, Burman W J, Eisenach K D, Dronda F, Bates J H, Cave M D. Usefulness of the secondary probe pTBN12 in DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1118–1123. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1118-1123.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin D P, DeRiemer K, Small P M, Ponce de Leon A, Steinhart R, Schecter G F, Daley C L, Moss A R, Paz E A, Paz A, Jasmer R M, Agasino C B, Hopewell P C. Differences in contributing factors to tuberculosis incidence in U.S.-born and foreign-born persons. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1797–1803. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9804029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dooley S W, Villarino M E, Lawrence M, Salinas L, Amil S, Rullan J V, Jarvis W R, Block A B, Cauthen G M. Nosocomial transmission of tuberculosis in a hospital unit for HIV-infected patients. JAMA. 1992;267:2632–2635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edlin B R, Tokars J I, Grieco M H, Crawford J T, Williams J, Sordillo E M, Ong K R, Kilburn J O, Dooley S W, Castro K G, Jarvis W R, Holmberg S D. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among hospitalized patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1514–1521. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206043262302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genewein A, Telenti A, Bernasconi C, Mordasini C, Weiss S, Maurer A M, Rieder H L, Schopfer K, Bodmer T. Molecular approach to identifying route of transmission of tuberculosis in the community. Lancet. 1993;342:841–844. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92698-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glynn J R, Bauer J, de Boer A S, Borgdorff M W, Fine P E M, Godfrey-Faussett P. Interpreting DNA fingerprint clusters of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:1055–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groenen P M A, Bunschoten A E, van Soolingen D, van Embden J D A. Nature of DNA polymorphism in the direct repeat cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis; application for strain differentiation by a novel typing method. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:1057–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jasmer R M, Hahn J A, Small P M, Daley C L, Behr M A, Moss A R, Creasman J M, Schecter G F, Paz E A, Hopewell P C. A molecular epidemiologic analysis of tuberculosis trends in San Francisco, 1991–1997. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:971–978. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-12-199906150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamerbeek J, Schouls L, Kolk A, van Agterveld M, van Soolingen D, Kuijper S, Bunschoten A, Molhuizen H, Shaw R, Goyal M, van Embden J. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:907–914. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.907-914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremer K, van Soolingen D, Frothingham R, Haas W H, Hermans P W M, Martín C, Palittapongarnpim P, Plikaytis B B, Riley L W, Yakrus M A, Musser J M, van Embden J D A. Comparison of methods based on different molecular epidemiological markers for typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: interlaboratory study of discriminatory power and reproducibility. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2607–2618. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2607-2618.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray M G, Thompson W F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:4321–4325. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearson M L, Jereb J A, Freiden T R, Crawford J T, Davis B J, Dooley S W, Jarvis W R. Nosocomial transmission of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:191–196. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-3-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross B C, Raios K, Jackson K, Dwyer B. Molecular cloning of a highly repeated DNA element from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its use as an epidemiological tool. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:942–946. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.942-946.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Small P M, McClenny N B, Singh S P, Schoolnik G K, Tomkins L S, Mickelsen P A. Molecular strain typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to confirm cross-contamination in the mycobacteriology laboratory and modification of procedures to minimize occurrence of false-positive cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1677–1682. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1677-1682.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Small P M, Hopewell P C, Singh S P, Paz A, Parsonnet J, Ruston D C, Schecter G F, Daley C L, Schoolnik G K. The epidemiology of tuberculosis in San Francisco, a population-based study using conventional and molecular methods. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1703–1709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406163302402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Small P M, Shafer R W, Hopewell P C, Singh S P, Desmond E, Sierra M F, et al. Exogenous reinfection with multidrug-resistant M. tuberculosis in patients with advanced HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1137–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304223281601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thierry D, Cave M D, Eisenach K D, Crawford J C, Bates J H, Gicquel B, Guesdon J L. IS6110, an IS-like element of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:188. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.1.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Embden J D A, Cave M D, Crawford J T, Dale J W, Eisenach K D, Gicquel B, Hermans P, Martin C, McAdam R, Shinnick T M, Small P M. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Rie A, Warren R, Richardson M, Victor T C, Gie R P, Enarson D A, Beyers N, van Helden P D. Exogenous reinfection as a cause of recurrent tuberculosis after curative treatment. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1174–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Soolingen D, Borgdorff M W, de Haas P E W, Sebek M M G G, Veen J, Dessens M, Kremer K, van Embden J D A. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in the Netherlands: a nation-wide study from 1993 through 1997. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:726–736. doi: 10.1086/314930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Soolingen D, Hermans P W M, de Haas P E W, Soll D R, van Embden J D A. Occurrence and stability of insertion sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: evaluation of an insertion sequence-dependent DNA polymorphism as a tool in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2578–2586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2578-2586.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Z, Chaves F, Barnes P F, Burman W J, Koehler J, Eisenach K D, Bates J H, Cave M D. Evaluation of method for secondary DNA typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with pTBN12 in epidemiologic study of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3044–3048. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3044-3048.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Z, Barnes P F, Chaves F, Eisenach K D, Weis S E, Bates J H, Cave M D. Diversity of DNA fingerprints of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1003–1007. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.1003-1007.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Z H, de Haas P E W, van Soolingen D, van Embden J D A, Andersen Å. Restriction fragment length polymorphism of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains isolated from Greenland during 1992: evidence of tuberculosis transmission between Greenland and Denmark. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:3018–3025. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.3018-3025.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Z H, de Haas P E W, Wachmann C H, van Soolingen D, van Embden J D A, Andersen Å. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in Denmark in 1992. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2077–2081. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2077-2081.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]