Abstract

There is growing evidence associating inflammatory markers in complex, higher order neurological functions, such as cognition and memory. We examined whether high levels of various inflammatory markers are associated with cognitive outcomes at 4 years of age in a mother-child cohort in Crete, Greece (Rhea study). We included 642 children in this cross-sectional study. Levels of several inflammatory markers (IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17α, IL-10, MΙP-1α, TNF-α and the ratios of IL-6 to IL-10 and TNF-α to IL-10) were determined in child serum via immunoassay. Neurodevelopment at 4 years was assessed by means of the McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities. Multivariate linear regression analyses were used to estimate the associations between the exposures and outcomes of interest after adjustment for various confounders. Our results indicate that children with high TNF-α concentrations (≥ 90th percentile) in serum demonstrated decreased scores in memory (adjusted β = −3.8; 95% CI: −7.5, −0.1), working memory (adjusted β = −4.4; 95% CI: −8.3, −0.5) as well as in memory span scale (adjusted β = −4.1; 95% CI: −7.9, −0.2). Children with “high” IL-6/IL-10 ratio showed lower scores in perceptual (adjusted β = −4.4; 95% CI: −8.3, −0.7) and motor scale (adjusted β = −5.2; 95% CI: −9.3, −1.2) and those with elevated TNF-α/IL-10 ratio demonstrated decreased memory span scores (adjusted β = −5.0; 95% CI: −9.0, −1.1). The findings suggest that high levels of TNF-α may contribute to reduced memory performance at preschool age.

Keywords: inflammation, inflammatory markers, cognition, memory, McCarthy Scales for Children’s Abilities

1. Introduction

Inflammation is identified as a natural defense mechanism by body tissues in response to injury, but this process may stop being protective for the organism and become harmful when it occurs chronically [1]. Inflammatory markers, such as cytokines, are proteins involved in normal aspects of neurodevelopment, including progenitor cell differentiation, cellular migration within the nervous system and synaptic network formation [2–6] and there is growing evidence associating them in complex, higher order neurological functions, such as cognition and memory [7, 8]. Imbalanced cytokine production, signaling and regulation may have various neurological consequences [9, 10].

Insight into the link of inflammatory markers function and central nervous system processes has increased, mostly on the basis of animal models. As Voltas et. al [11] recently pointed out, few studies have examined the potential association between child inflammatory biomarkers and neurodevelopment, and most of these studies were carried out with samples of extremely premature infants or with clinical samples of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). In fact, a body of research has evolved around the role of prenatal cytokines as markers of risk for cognitive dysfunction in special populations, such as children born preterm [12–14], children with low birth weight [15], sickle cell disease [16] and chronic hepatitis C [17], indicating a potential role for inflammatory processes in neurodevelopmental outcomes for those vulnerable populations. Some clinical studies have linked cytokine imbalances during development and throughout life to ASD; case-control studies have found higher circulating IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8 and TNF-α levels in plasma of preschool [18, 19] and school-age children with ASD [20–22] compared to typically developing controls. Moreover, plasma levels of IFN-γ and cerebrospinal fluid levels of TNF-α have been found to be increased in autistic children [23–25] and, likewise, elevated concentrations of IFN-γ have been reported for subjects with ASD compared to controls [20].

However, to our knowledge, there are no available data discussing the relationship between inflammatory markers levels and neurodevelopment in a general population sample of children. The aim of the present study is to examine the role of various inflammatory markers (IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-17α, MΙP-1α, TNF-α and two pro- to anti-inflammatory cytokine ratios, IL-6 to IL-10 and TNF-α to IL-10) measured in child serum at 4 years of age in neurodevelopmental scores assessed at 4 years of age in a cross-sectional study nested in the pregnancy cohort in Crete, Greece, after controlling for a range of confounders. It is hypothesized that increased levels of inflammation will be associated with elevated risk for inferior neurodevelopmental scores at 4 years of age.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

The Rhea study prospectively examines a population-based sample of pregnant women and their children at the prefecture of Heraklion, Crete, Greece. Methods are described in detail elsewhere [26]. Briefly, female residents (Greek and immigrants) who became pregnant during a period of one year starting in February 2007 were contacted and asked to participate in the study. The first contact was made at the time of the first major ultrasound examination (mean ± SD 12.0 ± 1.5 weeks) and several contacts followed (6th month of pregnancy, at birth, 6 months, 1st year and 4 years after birth). To be eligible for inclusion in the study, women had to have a good understanding of the Greek language and be older than 16 years of age. Face-to-face structured questionnaires along with self-administered questionnaires and medical records were used to obtain information on several psychosocial, dietary, and environmental exposures during pregnancy and early childhood. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures were approved by the ethical committee of the University Hospital in Heraklion, Crete, Greece. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants after complete description of the study.

The present analysis is a cross-sectional study, nested within the Rhea cohort. Out of 1363 singleton live births, 879 singleton children participated at the 4 years follow-up of the study, during which inflammation markers were measured in 661 children. From those, complete data for neurodevelopment was available for 642 children. Of those, 59 children had incomplete information regarding pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking early in pregnancy, parity, birth weight, preterm birth, BMI at the age of 4 and passive smoking of the child at 4 years of age. Thus, full data was available for a total of 583 children (90.8% of the children with exposure data and outcome assessment). We observed differences in some of the exposures and outcome data (p<0.05) between the children that had full data available (n=583) and those that had incomplete covariate information (n=59). Due to those differences, the incomplete covariate information was imputed.

2.2. Biological sample collection and exposure assessment

Following the completion of the 4-year-follow–up assessments, blood samples were collected by venipuncture for each child (10ml) in SST gel separator vacutainer (BD vacutainers, UK), after written parental consent. For the reduction of pain and discomfort of the children, anesthetic cream 5% EMLA with composition 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine (AsraZeneca, UK) was used. Analyses were performed in the Laboratory of Clinical Nutrition and Epidemiology of Diseases of Medical School, University of Crete. Blood samples were centrifuged (Kubota4000, Japan) at 2500rpm 10min within 2 hrs after collection and stored at −80o C until assayed. The Milliplex Map human high sensitivity T cell magnetic bead panel (Cat. # HSTCMAG-28SK) from Millipore (Billerica, MA) was used for the simultaneous quantification of IFN-γ IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-17α, MIP-1α and TNF-α in the supernatants. The principle of the assay is based on the quantification of multiple bio-molecules concurrently employing fluorescent-coded magnetic beads (MagPlex-C microspheres). The microspheres were incubated with the samples and then were allowed to pass rapidly through laser systems that distinguish the different sets of microspheres and the fluorescent dyes on the reporter bio-molecules. The sensitivity of the assay for every bio-molecule was: 0.3 pg/ml IFN-γ, 0.1 pg/ml IL-1β, 0.1 pg/ml IL-6, 0.1 pg/ml IL-8, 0.6 pg/ml IL-10, 0.3 pg/ml IL-17α, 0.9 pg/ml MIP-1α and 0.2 pg/ml TNF-α. The intra-assay precision (%CV) for all biomolecules was <5%. The inter-assay precision (%CV) for IFNγ, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-17α was <20%, for IL-1β, IL-8, MIP-1α and TNF-α was <15%. The above analyses were performed on an automated analyzer Luminex 100 connected with the Luminex xPONENT software.

2.3. Outcome assessment

McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities (MSCA)

Children’s cognitive and motor development was assessed by two trained psychologists, with the McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities (MSCA), at the 4 year clinical visit at the University Hospital of Heraklion, Greece. In brief, MSCA test aims to identify possible developmental delay in different skills with the use of six scales: the Verbal, the Perceptual-Performance, the Quantitative, the General Cognitive, the Memory and the Motor scale [27]. Executive function, working memory and memory span are three additional scales derived from the MSCA test in accordance with their association with specific neurocognitive function areas [28].

The translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the MSCA was performed according to the internationally recommended methodology. Children were assigned to the two psychologists at random. The inter-observer variability was <1%. Right after each MSCA assessment psychologists completed a brief report regarding difficulties encountered during administration, such as child’s behavior (bad moods, nervousness) and physical condition (tiredness, colds). This report was used for creating the quality of assessment index for the MSCA, which was flagged as “good”, “bad” or “very bad”. Additional information on children’s behavior was obtained via maternal report on standardized child behavior scales which were administered at the 4 years of age follow-up.

Raw scores of the neurodevelopmental assessment scales were standardized for child’s age at test administration using a method for the estimation of age-specific reference intervals based on fractional polynomials [29]. Standardized residuals were then typified having a mean of 100 points with a 15 SD to homogenize the scales (parameters conventionally used in psychometrics for IQ assessment). Scores were treated as continuous variables with higher scores representing better performance.

2.4. Statistical analysis

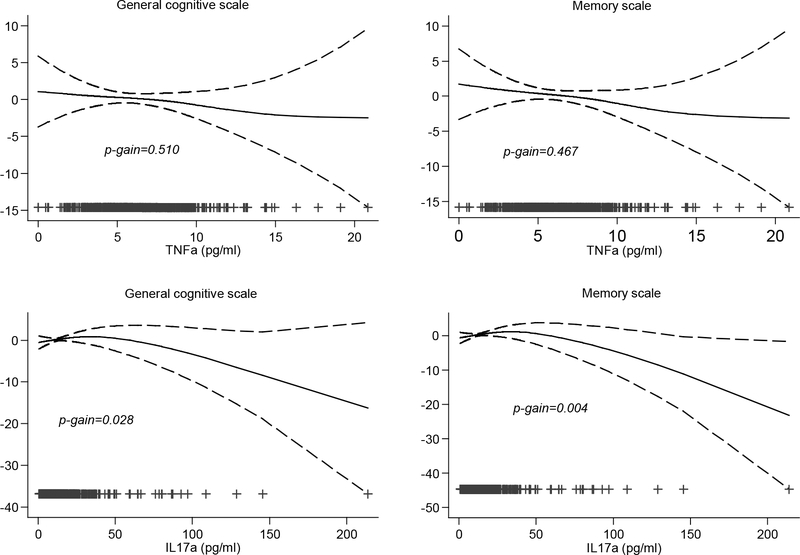

Descriptive analysis of the study population was conducted. Inflammatory marker levels were not normally distributed. Thus various transformations were applied, including logarithmic and square root. Still the normality assumption was not met. We fitted generalized additive models (GAMs) in order to explore the linearity of exposure–outcome associations. We found evidence of nonlinear associations of inflammatory markers with outcomes (p-gain, defined as the difference in normalized deviance between the GAM model and the linear model for the same exposure and outcome >0.1) (Figure 1). Therefore,.inflammatory levels in child serum were treated as categorical variables; the categories were defined as the “high exposure group” (≥90th percentile) and the reference group (<90th percentile). This categorization was also decided upon graphical inspection of the relationship between outcomes and exposures after the application of a spline knot; some of these associations are presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Adjusted associations (95% CIs) of TNF-α and IL-17α with child general cognitive and memory scale at 4 years of age. All models were adjusted for examiner, quality of assessment, child sex, maternal age in pregnancy, maternal education, BMI pre-pregnancy, parity, passive smoking at 4 years, birth weight, preterm birth and BMI at 4 years

Multivariate regression models were used to examine the association between cytokine levels and children’s neurodevelopmental outcomes at age of 4. Estimated associations were described in terms of β-coefficients and their 95% confidence intervals (CI); the significance of the β-coefficients was evaluated by the Wald’s test. The selection of the confounders was based on a priori knowledge using Directed Acyclic Diagrams (DAGs) (Supplementary figure 2). The first model (crude model) was adjusted for quality of MSCA assessment (good, bad, very bad) and examiner (psychologist 1, psychologist 2). The second model (minimally adjusted model) was additionally adjusted for child sex (male, female), and maternal characteristics, such as maternal age in pregnancy (years), maternal education [low level: ≤ 9 years of mandatory schooling, medium level: > 9 years of schooling up to attending post-secondary school education and high level: attending university or having a university/technical college degree] parity (primiparous, multiparous) and maternal pre-pregnancy Body Mass Index (BMI). The third model (fully adjusted model - confounding by child characteristics) was adjusted for the variables in the second model plus passive smoking at 4 years (yes, no), birth weight (g), preterm birth (yes, no) and child BMI at 4 years (kg/m2).

In order to assess if our studied associations were modified by child sex, child BMI at 4 years (normal weight vs. overweight or obese), maternal pre-pregnancy BMI (normal weight vs. overweight or obese) or child nursery attendance (yes/no), appropriate interaction terms were included in the regression models. We stratified the sample in the cases that significant interactions were detected. Moreover we performed sensitivity analyses excluding preterm (<37 gestational weeks) and low birth weight (<2500g) neonates.

Due to the relatively high percentage of missing covariates (9.2%) we used multiple imputations with chained equations (MICE) in order to increase precision and reduce bias. The imputation model included exposures, outcomes, and covariates under study, as well as additional auxiliary variables [30]. In analytic models, we combined estimates from the 20 imputed data sets generated with the use of Rubin’s rules [31]. Results were similar between multiple imputation and complete case analysis, and hence, we present effect estimates based on imputed data.

All hypothesis testing was conducted assuming a 0.05 significance level and a 2-sided alternative hypothesis. The standardization of the MSCA and all other statistical analyses were performed using Stata Software, version 13 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

Table 1 describes the study population characteristics. Participating mothers were predominantly Greek (94.7%) and had a mean (±SD) age of 29.8 (±5.0) years. About half of them had medium educational level (51.7%) and were multiparous (53.5%). Before pregnancy, the mean maternal BMI was 24.5 (±4.7) kg/m2. About half of the children (52.3%) were boys, the mean (±SD) birth weight of the study population was 3195.4 (±449.2) g and the mean age at assessment was 4.2 (±0.2) years. A total of 280 (43.8%) were exposed to passive smoking and the mean (±SD) BMI at age 4 was 16.4 (±1.8) kg/m2.

Table 1.

Study participants characteristics

| Total |

||

|---|---|---|

| N | % or Mean ± SD | |

|

| ||

| Maternal characteristics | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 634 | 29.8±5.0 |

| Ethnic origin | ||

| Greek | 602 | 94.7 |

| Other | 34 | 5.3 |

| Education | ||

| Low | 95 | 15.3 |

| Medium | 320 | 51.7 |

| High | 204 | 33.0 |

| Parity | ||

| Primiparous | 298 | 46.5 |

| Multiparous | 343 | 53.5 |

| BMI before pregnancy (kg/m2) | 608 | 24.5±4.7 |

| Child characteristics | ||

| Sex | ||

| Boy | 336 | 52.3 |

| Girl | 306 | 47.7 |

| Age at 4 years follow-up | 642 | 4.2±0.2 |

| Birth weight (g) | 618 | 3195.4±449.2 |

| Preterm birth | 669 | 4.1±4.3 |

| Yes | 74 | 11.8 |

| No | 551 | 88.2 |

| BMI at age 4 (kg/m2) | 640 | 16.4±1.8 |

| Passive smoking at age 4 | ||

| Yes | 280 | 43.8 |

| No | 359 | 56.2 |

Child inflammatory levels in serum at 4 years are presented in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1 illustrates correlation coefficients calculated for all those markers.

Table 2.

Child inflammatory levels at 4 years of age (pg/ml, n = 642)

| Inflammatory Marker | Median (IQR) | Geometric Mean (GSD) | Percentile |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 90th | |||

|

| ||||

| IL-6 pg/ml | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.08 (2.22) | 0.5 | 2.4 |

| IL-1β pg/ml | 1.3 (1.0) | 1.06 (2.59) | 0.5 | 2.4 |

| IFN-γ pg/ml | 26.3 (23.0) | 21.58 (3.07) | 6.5 | 52.9 |

| IL-8 pg/ml | 3.5 (1.9) | 3.58 (1.62) | 2.2 | 5.9 |

| IL-10 pg/ml | 5.4 (5.1) | 5.18 (2.34) | 2.1 | 13.5 |

| IL-17α pg/ml | 11.2 (12.1) | 11.06 (2.59) | 4.1 | 29.3 |

| MIP-1α pg/ml | 13.4 (7.7) | 12.40 (1.75) | 6.9 | 21.2 |

| TNF-α pg/ml | 6.0 (3.1) | 5.73 (1.60) | 3.4 | 9.4 |

GSD: Geometric Standard Deviation

Table 3 shows regression results for high inflammatory marker levels in child serum in relation to neurodevelopmental outcomes (MSCA scores) at 4 years of age. Children with high TNF-α serum levels (≥ 90th percentile) demonstrated decreased scores in memory (adjusted β = −3.8; 95% CI: −7.5, −0.1), working memory (adjusted β = −4.4; 95% CI: −8.3, −0.5) as well as in memory span scale (adjusted β = −4.1; 95% CI: −7.9, −0.2). High IL-6/IL-10 ratio was associated with lower scores in perceptual performance (adjusted β = −4.4; 95% CI: −8.3, −0.7) and motor scale (adjusted β = −5.2; 95% CI: −9.3, −1.2), as well as high TNF-α/IL-10 ratio was associated with decreased memory span scores (adjusted β = −5.0; 95% CI: −9.0, −1.1). No other association was detected between high inflammatory levels and other neurodevelopmental scores at 4 years of age.

Table 3:

Adjusted associations (β coefficients & 95% CIs) of child inflammatory markers levels with MSCA scales at 4 years of age (n = 634)

| Verbal | Perceptual | Quantitative | Motor | Exec. Function | General cognitive | Memory | Working memory | Memory span | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| beta (95% CI) | beta (95% CI) | beta (95% CI) | beta (95% CI) | beta (95% CI) | beta (95% CI) | beta (95% CI) | beta (95% CI) | beta (95% CI) | |

|

| |||||||||

| Markers with pro-inflammatory activity | |||||||||

| IFN-γ 1 | −2.6 (−6.2, 0.9) | 2.0 (−1.6, 5.6) | −1.2 (−5.0, 2.6) | 2.0 (−1.9, 5.9) | −1.8 (−5.4, 1.7) | −1.1 (−4.7, 2.4) | −3 (−6.7, 0.7) | −2.4 (−6.2, 1.5) | −3.2 (−7.0, 0.5) |

| IL-1β 1 | −1.6 (−5.2, 2.0) | −1.9 (−5.5, 1.8) | 1 (−2.8, 4.9) | −1.7 (−5.7, 2.3) | −0.5 (−4.1, 3.2) | −1.5 (−5.1, 2.1) | −1.9 (−5.6, 1.9) | 2.1 (−1.8, 6.1) | −2.3 (−6.1, 1.5) |

| IL-6 1 | 2.2 (−1.4, 5.8) | 0.4 (−3.3, 4.1) | 0.6 (−3.2, 4.5) | 1.6 (−2.3, 5.6) | 1.3 (−2.4, 4.9) | 1.4 (−2.2, 5.1) | 2.7 (−1.1, 6.4) | 0.8 (−3.2, 4.8) | 2.7 (−1.1, 6.6) |

| IL-8 1 | −2.5 (−6.1, 1.2) | −1 (−4.7, 2.7) | −1.8 (−5.7, 2.0) | 0.6 (−3.4, 4.6) | −2.1 (−5.8, 1.6) | −2.2 (−5.9, 1.4) | −2.4 (−6.1, 1.4) | −2.7 (−6.7, 1.3) | −1.5 (−5.3, 2.4) |

| TNF-α 1 | −3.1 (−6.7, 0.5) | −1.2 (−4.9, 2.4) | −3.4 (−7.2, 0.4) | −1.8 (−5.8, 2.1) | −2.8 (−6.4, 0.9) | −2.9 (−6.5, 0.7) | −3.8 (−7.5, -0.1) | −4.4 (−8.3, -0.5) | −4.1 (−7.9, -0.2) |

| IL-17α 1 | 0.0 (−3.7, 3.7) | −3.3 (−7, 0.5) | 0.3 (−3.7, 4.2) | −3.3 (−7.3, 0.8) | −0.8 (−4.6, 2.9) | −1.4 (−5.1, 2.3) | −0.6 (−4.4, 3.3) | 0.3 (−3.8, 4.3) | −1.2 (−5.2, 2.7) |

| MIP-1α 1 | 0.2 (−3.4, 3.9) | −1.3 (−5, 2.4) | 0.3 (−3.5, 4.2) | 0.5 (−3.5, 4.5) | 0.8 (−2.9, 4.5) | −0.4 (−4.1, 3.2) | −1.3 (−5.0, 2.5) | 0.6 (−3.4, 4.6) | −1.3 (−5.1, 2.6) |

| Markers with anti-inflammatory activity | |||||||||

| IL-10 1 | 0.7 (−3.0, 4.3) | 2.2 (−1.5, 5.9) | 0.6 (−3.2, 4.5) | 2.0 (−2.0, 6.0) | 1.9 (−1.8, 5.5) | 1.3 (−2.4, 4.9) | −0.2 (−4.0, 3.6) | −0.7 (−4.7, 3.2) | 0.8 (−3.1, 4.6) |

| Ratios | |||||||||

| IL-6/IL10 1 | −1.4 (−5.2, 2.3) | −4.4 (−8.3, -0.7) | −3.6 (−7.5, 0.4) | −5.2 (−9.3, -1.2) | −3.7 (−7.4, 0) | −3.5 (−7.2, 0.2) | −1.3 (−5.2, 2.5) | −2.5 (−6.6, 1.5) | −1.9 (−5.8, 2.0) |

| TNF-α/IL-10 1 | −1.5 (−5.3, 2.3) | −3.5 (−7.3, 0.2) | −3.5 (−7.5, 0.4) | −2.4 (−6.5, 1.7) | −3.7 (−7.5, 0) | −2.9 (−6.7, 0.8) | −3.4 (−7.2, 0.5) | −2.9 (−7.0, 1.2) | −5.0 (−9.0, -1.1) |

≥90th percentile

All models are adjusted for examiner, quality of assessment, child sex, maternal age in pregnancy, maternal education, BMI pre-pregnancy, parity, passive smoking at 4 years, birth weight, preterm birth and BMI at 4 years

Further analyses showed evidence for an interaction between child sex and IL-17α levels in response to neurodevelopmental scores (p for interaction < 0.05). Stratified analysis revealed reduced verbal (adjusted β = −5.8; 95% CI: −11.7, 0.1), memory (adjusted β = −5.3; 95% CI: −11.4, 0.7), working memory (adjusted β = −4.8; 95% CI: −11.3, 1.8) and memory span (adjusted β = −6.1; 95% CI: −12.3, −0.1) scale scores for boys with high concentrations of IL-17a, whereas these associations in girls were in the opposite direction (Supplementary table 2). Moreover, boys with high concentrations of IL-6 had lower perceptual (adjusted β = −3.2; 95% CI: −8.5, 2.0) and motor (adjusted β = −3.2; 95% CI: −8.9, 2.6) scale scores (Supplementary Table 2). Further stratified analysis according to child BMI status, showed reduced scores in memory (adjusted β = −11.6; 95% CI: −20.8, −2.5) and memory span (adjusted β = −11.5; 95% CI: −20.3, −2.7) scales for overweight/obese children with high concentrations of TNF-α in serum, whereas similar associations in children with normal weight were not significant. We also found decreased motor scores (adjusted β = −13.2; 95% CI: −23.7, −2.8) for overweight/obese children with high IL-6/IL-10 ratio (Supplementary Table 3). We found no evidence for any significant interaction between maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity or child nursery attendance and child high inflammatory biomarker levels at 4 years of age (p for interaction > 0.05). Sensitivity analyses excluding preterm newborns (<37 gestational weeks) and low birth weight neonates (<2500 g) did not meaningfully change our results (data not shown).

4. Discussion

In the present analysis we examined for the first time the relationship between inflammatory marker levels and neurodevelopment in a general population sample of children and found that preschoolers with elevated TNF-α concentrations in serum demonstrated decreased scores in memory, memory span and working memory tasks. These associations persisted after the sequential adjustment for several maternal and child factors. Elevated levels of the rest inflammatory markers under examination (IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17α, IL-10 and MΙP-1α) were not associated with any other child neurodevelopmental scores.

Comparison with other studies is rather complex mainly because of different methodological approaches study design, type and size of study samples, age of the participants and outcomes examined. Studies with elderly populations have well-established the association between TNF-α levels with cognitive deficits. Elevated TNF-α serum concentrations have been detected in patients with cognitive decline, such as Alzheimer’s disease [32–34] suggesting that TNF-α-driven processes may contribute to cognitive and memory deficits of the disease and that inhibition of TNF-α can be effective for treating it [35–38]. In addition, a study conducted with adult patients with depressive disorder demonstrated that elevated expression of TNF-α, TNFRSF1A and TNFRSF1B genes correlates negatively, among others, with working memory, direct and delayed auditory-verbal memory and effectiveness of learning processes and verbal fluency [39].

Available data on child inflammation and neurodevelopmental outcomes are mainly based on ASD samples; a recent cross-sectional study investigating the association between peripheral cytokine levels (including TNF-α) and cognitive profiles in children with ASD found negative correlations of IL-6 and IFN-γ serum levels with WISC verbal comprehension index and working memory index respectively, suggesting that cytokines may play a role in the neural development in ASD [40].

In general, inflammatory signaling is considered to be a critical contributor to the short-and long term regulation of mood and cognition, but the exact mechanisms by which cytokines may modulate memory remain unknown [41]. TNF-α concentrations are found elevated in various neuropathological states that are related to learning and memory deficits, highlighting a possible role in plasticity [42]. For this purpose, much work has been carried out in the hippocampus; in fact, animal studies provide evidence that mice over-expressing TNF-α demonstrate memory impairments and disrupted learning capabilities [43, 44], supporting the notion that TNF-α activity at the hippocampus and the synaptic level may influence brain function and behavior [45, 46]. Consistently, a negative effect of TNF-α was found following intra-hippocampal administration to rats, which lead to impaired hippocampal-dependent working memory, as shown by an increased number of errors and longer latencies regarding the runway task [47]. Moreover, increased TNF-α in rats following peripheral nerve injury may not only contribute to chronic pain, but also to memory deficits by dysfunction of hippocampus [48]. A study conducted in adults showed that higher concentrations of TNF-α are associated with smaller hippocampal volumes suggesting that the balance between the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis and inflammation processes might explain hippocampal volume reductions [49].

We also found that high IL-6/IL-10 ratio was associated with lower scores in perceptual performance and motor scale as well as high TNF-α/IL-10 ratio was related to decreased memory span scores. Since this is the first study illustrating the associations of these ratios with child cognitive domains, further data is required to validate these results and clarify the underlying mechanisms of these findings.

Our results showed greater risk for reduced verbal, memory, working memory and memory span performance for boys with high IL-17α serum concentrations, as well as reduced perceptual and motor performance for boys with high IL-6 serum concentrations. To our knowledge, this is the first study revealing sex-related differences in inflammation-specific cognitive domain associations in children. Although further study is required to validate and clarify the underlying mechanisms and the clinical utility of these findings, increased male prevalence has been frequently reported in various neurodevelopmental disorders, highlighting the concept of a male vulnerability model [50]. It is hypothesized that this male susceptibility occurs partly because microglia and inflammatory molecules are involved in the normal developmental process of sexual differentiation [51] and also because males have more activated innate immune cells in the developing brain under normal conditions [52]. We also found greater risk for lower scores in memory and memory span scales for overweight/obese children with high TNF-α serum concentrations. This finding is in line with evidence from human clinical studies showing that obesity may increase the risk of mild cognitive impairment, in the form of short-term memory and executive function deficits [53]. Obesity is considered to be a low-grade pro-inflammatory state, and studies have reported low-grade elevation of TNF-α in obese individuals [54–56]. Research in rodent models show that obesity-induced inflammation may directly interfere with synaptic communication in the hippocampus [57].

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations; the cross-sectional design of the study does not permit inferences on causality. Although we incorporated extensive information on potential child and social factors that are associated with child neurodevelopment, we acknowledge that residual confounding because of other unmeasured confounders may still occur. On the other hand, the strengths of the present study include the heterogeneous and relatively large sample size. In addition, we carefully assessed neurodevelopmental data using a robust instrument such as MSCA [27], a valid, standardized psychometric test which provides both a general level of child’s intellectual functioning and an assessment of separate neurodevelopmental domains. Moreover, we used multiple imputations with chained equations in order to increase precision and reduce bias.

To our knowledge, this the first study conducted in a general population sample of children which highlights the significant role of increased TNF-α levels during preschool years in child memory performance. As there are no studies to this date that analyzed how inflammatory biomarkers relate to measures of neurodevelopmental scores in a general population sample, these results may shed some light in new pathways of investigation. Our findings reinforce the existing evidence that elevated inflammatory activity may be involved in early pathophysiological processes, such as memory deficits and further investigation on the meaning of these associations can provide new insights. The follow-up of this cohort could provide additional data about the potential predictive role of those biomarkers and elucidate some of the questions raised by the results. .

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would particularly like to thank all the cohort participants for their generous collaboration.

The Rhea project was financially supported by European projects (EU FP6-2003-Food-3-NewGeneris, EU FP6. STREP Hiwate, EU FP7 ENV.2007.1.2.2.2. Project No 211250 Escape, EU FP7-2008-ENV-1.2.1.4 Envirogenomarkers, EU FP7-HEALTH-2009-single stage CHICOS, EUFP7 ENV.2008.1.2.1.6. Proposal No 226285 ENRIECO, EUFP7- HEALTH-2012 Proposal No 308333 HELIX), MeDALL (FP7 European Union project, No. 264357), and the Greek Ministry of Health (Program of Prevention of obesity and neurodevelopmental disorders in preschool children, in Heraklion district, Crete, Greece: 2011–2014; “Rhea Plus”: Primary Prevention Program of Environmental Risk Factors for Reproductive Health, and Child Health: 2012–15).

List of abbreviations:

- IFN-γ

Interferon γ

- IL-1β

Interleukin 1β

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- IL-8

Interleukin 8

- IL-17α

Interleukin 17α

- IL-10

Interleukin 10

- MΙP-1α

Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 1α

- TNF-α

Tumor Necrosis Factor α

- ASD

Autism Spectrum Disorders

- DAGs

Directed Acyclic Graphs

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- IQ

Intelligence Quotient

- MSCA

McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities

- SD

Standard Deviation

- 95% CI

95% Confidence Interval

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Medzhitov R, Origin and physiological roles of inflammation, Nature 454(7203) (2008) 428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Deverman BE, Patterson PH, Cytokines and CNS Development, Neuron 64(1) (2009) 61–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bauer S, Kerr BJ, Patterson PH, The neuropoietic cytokine family in development, plasticity, disease and injury, Nature Reviews Neuroscience 8(3) (2007) 221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rostene W, Kitabgi P, Parsadaniantz SM, Chemokines: a new class of neuromodulator?, Nature Reviews Neuroscience 8(11) (2007) 895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Boulanger LM, Immune proteins in brain development and synaptic plasticity, Neuron 64(1) (2009) 93–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Onore C, Careaga M, Ashwood P, The role of immune dysfunction in the pathophysiology of autism, Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 26(3) (2012) 383–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].McAfoose J, Baune BT, Evidence for a cytokine model of cognitive function, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 33(3) (2009) 355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wilson CJ, Finch CE, Cohen HJ, Cytokines and cognition—the case for a head-to-toe inflammatory paradigm, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 50(12) (2002) 2041–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Goines PE, Ashwood P, Cytokine dysregulation in autism spectrum disorders (ASD): Possible role of the environment, Neurotoxicology and Teratology 36 (2013) 67–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM, Early-life programming of later-life brain and behavior: a critical role for the immune system, Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 3 (2009) 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Voltas N, Arija V, Hernández-Martínez C, Jiménez-Feijoo R, Ferré N, Canals J, Are there early inflammatory biomarkers that affect neurodevelopment in infancy?, Journal of Neuroimmunology 305 (2017) 42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].O’Shea TM, Joseph RM, Kuban KC, Allred EN, Ware J, Coster T, Fichorova RN, Dammann O, Leviton A, Elevated blood levels of inflammation-related proteins are associated with an attention problem at age 24 months in extremely preterm infants, Pediatric research 75(6) (2014) 781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kuban KC, O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Fichorova RN, Heeren T, Paneth N, Hirtz D, Dammann O, Leviton A, Investigators ES, The breadth and type of systemic inflammation and the risk of adverse neurological outcomes in extremely low gestation newborns, Pediatric neurology 52(1) (2015) 42–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Leviton A, Joseph RM, Allred EN, Fichorova RN, O’Shea TM, Kuban KKC, Dammann O, The risk of neurodevelopmental disorders at age 10 years associated with blood concentrations of interleukins 4 and 10 during the first postnatal month of children born extremely preterm, Cytokine 110 (2018) 181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Carlo WA, McDonald SA, Tyson JE, Stoll BJ, Ehrenkranz RA, Shankaran S, Goldberg RN, Das A, Schendel D, Thorsen P, Cytokines and neurodevelopmental outcomes in extremely low birth weight infants, The Journal of pediatrics 159(6) (2011) 919–925. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Andreotti C, King AA, Macy E, Compas BE, DeBaun MR, The association of cytokine levels with cognitive function in children with sickle cell disease and normal MRI studies of the brain, Journal of child neurology (2014) 0883073814563140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Abu Faddan N., Shehata G, Abd Elhafeez H., Mohamed A, Hassan H, Abd El Sameea F., Cognitive function and endogenous cytokine levels in children with chronic hepatitis C, Journal of viral hepatitis 22(8) (2015) 665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ashwood P, Krakowiak P, Hertz-Picciotto I, Hansen R, Pessah I, Van de Water J, Elevated plasma cytokines in autism spectrum disorders provide evidence of immune dysfunction and are associated with impaired behavioral outcome, Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 25(1) (2011) 40–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ashwood P, Krakowiak P, Hertz-Picciotto I, Hansen R, Pessah IN, Van de Water J, Altered T cell responses in children with autism, Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 25(5) (2011) 840–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Suzuki K, Matsuzaki H, Iwata K, Kameno Y, Shimmura C, Kawai S, Yoshihara Y, Wakuda T, Takebayashi K, Takagai S, Plasma cytokine profiles in subjects with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders, PLoS One 6(5) (2011) e20470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yang C-J, Tan H-P, Yang F-Y, Liu C-L, Sang B, Zhu X-M, Du Y-J, The roles of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines in assisting the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 9 (2015) 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jyonouchi H, Sun S, Le H, Proinflammatory and regulatory cytokine production associated with innate and adaptive immune responses in children with autism spectrum disorders and developmental regression, Journal of Neuroimmunology 120(1) (2001) 170–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Singh VK, Plasma increase of interleukin-12 and interferon-gamma. Pathological significance in autism, Journal of Neuroimmunology 66(1) (1996) 143–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chez MG, Dowling T, Patel PB, Khanna P, Kominsky M, Elevation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in cerebrospinal fluid of autistic children, Pediatric neurology 36(6) (2007) 361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].El-Ansary A, Al-Ayadhi L, Neuroinflammation in autism spectrum disorders, Journal of neuroinflammation 9(1) (2012) 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chatzi L, Leventakou V, Vafeiadi M, Koutra K, Roumeliotaki T, Chalkiadaki G, Karachaliou M, Daraki V, Kyriklaki A, Kampouri M, Cohort Profile: The Mother-Child Cohort in Crete, Greece (Rhea Study), International Journal of Epidemiology 46(5) (2017) 1392–1393k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McCarthy D, Manual for the McCarthy scales of children’s abilities, Psychological Corp, New York, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Julvez J, Ribas-Fitó N, Torrent M, Forns M, Garcia-Esteban R, Sunyer J, Maternal smoking habits and cognitive development of children at age 4 years in a population-based birth cohort, International Journal of Epidemiology 36(4) (2007) 825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Royston P, Wright EM, A method for estimating age-specific reference intervals (‘normal ranges’) based on fractional polynomials and exponential transformation, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 161(1) (1998) 79–101. [Google Scholar]

- [30].White IR, Royston P, Wood AM, Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice, Statistics in medicine 30(4) (2011) 377–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Rubin DB, Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys, John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tan Z, Beiser A, Vasan R, Roubenoff R, Dinarello C, Harris T, Benjamin E, Au R, Kiel D, Wolf P, Inflammatory markers and the risk of Alzheimer disease The Framingham Study, Neurology 68(22) (2007) 1902–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Álvarez A, Cacabelos R, Sanpedro C, García-Fantini M, Aleixandre M, Serum TNF-alpha levels are increased and correlate negatively with free IGF-I in Alzheimer disease, Neurobiology of Aging 28(4) (2007) 533–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Swardfager W, Lanctôt K, Rothenburg L, Wong A, Cappell J, Herrmann N, A meta-analysis of cytokines in Alzheimer’s disease, Biological Psychiatry 68(10) (2010) 930–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].McAlpine FE, Tansey MG, Neuroinflammation and tumor necrosis factor signaling in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease, Journal of inflammation research 1 (2008) 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Holmes C, Cunningham C, Zotova E, Woolford J, Dean C, S.u. Kerr, D. Culliford, V. Perry, Systemic inflammation and disease progression in Alzheimer disease, Neurology 73(10) (2009) 768–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tobinick E, Tumour necrosis factor modulation for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, CNS drugs 23(9) (2009) 713–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Giuliani F, Vernay A, Leuba G, Schenk F, Decreased behavioral impairments in an Alzheimer mice model by interfering with TNF-alpha metabolism, Brain research bulletin 80(4) (2009) 302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bobińska K, Gałecka E, Szemraj J, Gałecki P, Talarowska M, Is there a link between TNF gene expression and cognitive deficits in depression?, Acta Biochimica Polonica 64(1) (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sasayama D, Kurahashi K, Oda K, Yasaki T, Yamada Y, Sugiyama N, Inaba Y, Harada Y, Washizuka S, Honda H, Negative Correlation between Serum Cytokine Levels and Cognitive Abilities in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Journal of Intelligence 5(2) (2017) 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Donzis EJ, Tronson NC, Modulation of learning and memory by cytokines: signaling mechanisms and long term consequences, Neurobiology of learning and memory 115 (2014) 68–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Pickering M, Cumiskey D, O’Connor JJ, Actions of TNF-α on glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the central nervous system, Experimental physiology 90(5) (2005) 663–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Aloe L, Properzi F, Probert L, Akassoglou K, Kassiotis G, Micera A, Fiore M, Learning abilities NGF and BDNF brain levels in two lines of TNF-α transgenic mice, one characterized by neurological disorders, the other phenotypically normal, Brain research 840(1) (1999) 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fiore M, Angelucci F, Alleva E, Branchi I, Probert L, Aloe L, Learning performances, brain NGF distribution and NPY levels in transgenic mice expressing TNF-alpha, Behavioural Brain Research 112(1) (2000) 165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tonelli LH, Postolache TT, Sternberg EM, Inflammatory genes and neural activity: involvement of immune genes in synaptic function and behavior, Front Biosci 10 (2005) 675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Golan H, Levav T, Mendelsohn A, Huleihel M, Involvement of tumor necrosis factor alpha in hippocampal development and function, Cerebral Cortex 14(1) (2004) 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Matsumoto Y, Watanabe S, Suh YH, Yamamoto T, Effects of intrahippocampal CT105, a carboxyl terminal fragment of β-amyloid precursor protein, alone/with inflammatory cytokines on working memory in rats, Journal of neurochemistry 82(2) (2002) 234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ren W-J, Liu Y, Zhou L-J, Li W, Zhong Y, Pang R-P, Xin W-J, Wei X-H, Wang J, Zhu H-Q, Peripheral nerve injury leads to working memory deficits and dysfunction of the hippocampus by upregulation of TNF-α in rodents, Neuropsychopharmacology 36(5) (2011) 979–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sudheimer KD, O’Hara R, Spiegel D, Powers B, Kraemer HC, Neri E, Weiner M, Hardan A, Hallmayer J, Dhabhar FS, Cortisol, cytokines, and hippocampal volume interactions in the elderly, Frontiers in aging neuroscience 6 (2014) 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Jacquemont S, Coe BP, Hersch M, Duyzend MH, Krumm N, Bergmann S, Beckmann JS, Rosenfeld JA, Eichler EE, A higher mutational burden in females supports a “female protective model” in neurodevelopmental disorders, The American Journal of Human Genetics 94(3) (2014) 415–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lenz KM, Nugent BM, Haliyur R, McCarthy MM, Microglia are essential to masculinization of brain and behavior, Journal of Neuroscience 33(7) (2013) 2761–2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Schwarz JM, Sholar PW, Bilbo SD, Sex differences in microglial colonization of the developing rat brain, Journal of neurochemistry 120(6) (2012) 948–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Nguyen JCD, Killcross AS, Jenkins TA, Obesity and cognitive decline: role of inflammation and vascular changes, Frontiers in Neuroscience 8 (2014) 375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Yudkin JS, Stehouwer C, Emeis J, Coppack S, C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: associations with obesity, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction, Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 19(4) (1999) 972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Reinehr T, Stoffel-Wagner B, Roth CL, Andler W, High-sensitive C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor α, and cardiovascular risk factors before and after weight loss in obese children, Metabolism 54(9) (2005) 1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM, Adipose Expression of Tumor Necrosis Factor- : Direct Role in Obesity-Linked Insulin Resistance, SCIENCE-NEW YORK THEN WASHINGTON- 259 (1993) 87–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Erion JR, Wosiski-Kuhn M, Dey A, Hao S, Davis CL, Pollock NK, Stranahan AM, Obesity elicits interleukin 1-mediated deficits in hippocampal synaptic plasticity, Journal of Neuroscience 34(7) (2014) 2618–2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.