Abstract

Background

We previously conducted a concept elicitation study on the impact of Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative bacterial bloodstream infections (SAB/GNB) on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) from the patient’s perspective and found significant impacts on HRQoL, particularly in the physical and functional domains. Using this information and following guidance on the development of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures, we determined which combination of measures and items (ie, specific questions) would be most appropriate in a survey assessing HRQoL in bloodstream infections.

Methods

We selected a variety of measures/items from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) representing different domains. We purposefully sampled patients ~6–12 weeks post-SAB/GNB and conducted 2 rounds of cognitive interviews to refine the survey by exploring patients’ understanding of items and answer selection as well as relevance for capturing HRQoL.

Results

We interviewed 17 SAB/GNB patients. Based on the first round of cognitive interviews (n = 10), we revised the survey. After round 2 of cognitive interviewing (n = 7), we finalized the survey to include 10 different PROMIS short forms/measures of the most salient HRQoL domains and 2 adapted questions (41 items total) that were found to adequately capture HRQoL.

Conclusions

We developed a survey from well-established PRO measures that captures what matters most to SAB/GNB patients as they recover. This survey, uniquely tailored to bloodstream infections, can be used to assess these meaningful, important HRQoL outcomes in clinical trials and in patient care. Engaging patients is crucial to developing treatments for bloodstream infections.

Keywords: bacterial bloodstream infections, cognitive interviews, measure development, patient-reported outcomes, quality of life

Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative bacterial bloodstream infections (SAB and GNB, respectively) are common and serious [1, 2] infections that negatively impact survivors’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL), defined by and demonstrated across physical, functional, mental health/emotional, cognitive, and social domains [3]. Treatment of bloodstream infections often involves prolonged hospitalization, extended treatment and recovery times, and invasive procedures. These consequences of bloodstream infection can have prolonged negative effects on patients [4–6]. Most antibiotic trials focus on survival and microbiologic outcomes, which may not capture the entirety of what is important to patients. Clinician-directed actions such as antibiotic prescribing decisions often inform trial end points but may or may not reflect patients’ actual health status. Therefore, engaging patients with bloodstream infections and obtaining their feedback for clinical trials are critically important to ensure that the comparisons between treatments include patient-centered outcomes that are meaningful [7].

In our recent work (Phase 1), we conducted a qualitative descriptive study to elicit concepts regarding the impact of SAB and GNB on HRQoL from the patient’s perspective [3]. We found that these patients with diverse infection syndromes described similar experiences, but with varying levels of impact on HRQoL, particularly in the physical and functional domains, with impact also varying over time and across patients [3]. We concluded that 1 measure could be used for this spectrum of bloodstream infection types, provided it is able to capture a range in the level of impact on how the patient feels and functions.

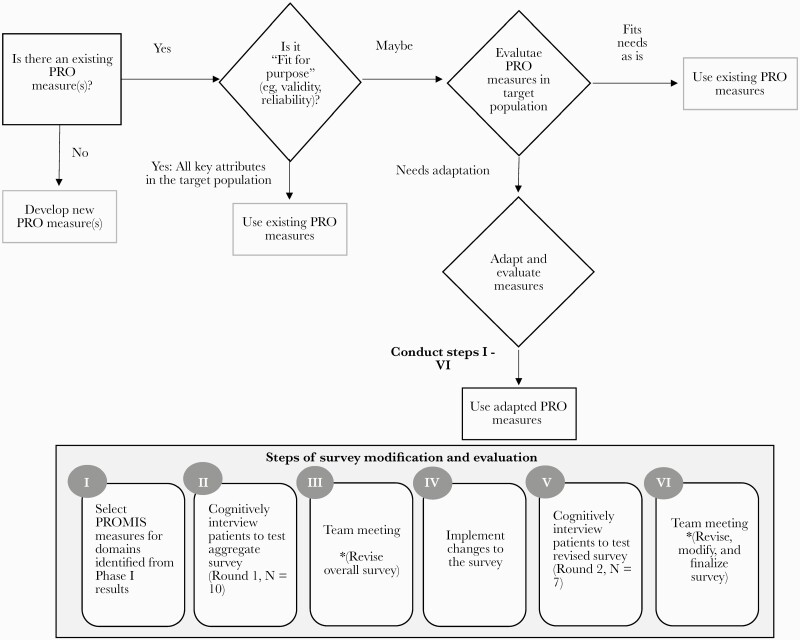

Guidance [8, 9], including from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), suggests that concept elicitation, such as that described above, is the first step in the patient-reported outcome (PRO) measurement development process. Guidance (Figure 1) also suggests that investigators should then consider using existing measures, when deemed appropriate based on concept elicitation findings [9, 10], to allow for comparability and to maximize efficiency, as it may take many years to develop a new measure. Therefore, our next steps, presented in this manuscript (Phase 2), were to align our Phase 1 concept elicitation findings with existing HRQoL measures across the relevant domains introduced above and to evaluate the extent to which a survey of those combined measures and items (ie, specific questions) are “fit for purpose”; that is, to what extent they adequately capture HRQoL in a sample of patients with bloodstream infections. This was done through cognitive interviews to assess if the survey works in the way intended for a specific target population and to add, remove, and/or modify measures and items to appropriately capture HRQoL [11]. Once established as being “fit for purpose,” the HRQoL survey can be used to evaluate the efficacy in trials of treatments for bloodstream infection or to inform clinical care of patients with SAB and GNB.

Figure 1.

Process flow diagram. Abbreviations: PRO, patient-reported outcome; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

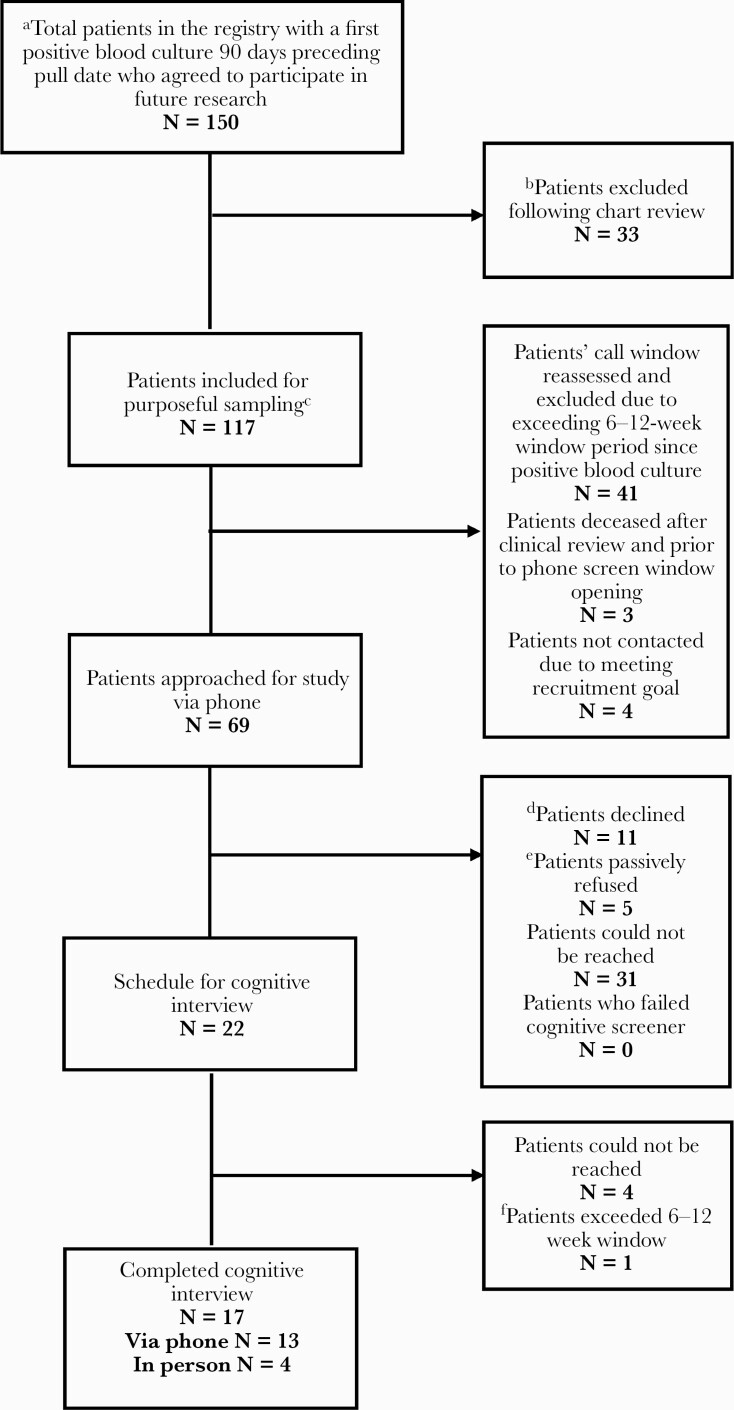

We prospectively enrolled Duke University Health System (DUHS) patients with SAB or with GNB from the Bloodstream Infections Registry (eIRB#: Pro00008031) as previously described [3]. We purposefully sampled to capture a range of patient experiences (Figure 2 provides details) ~6–12 weeks following their bloodstream infection informed by and extended based on our prior work [3]. We selected this time frame to capture the entirety of the course of treatment and complications, mirror typical time points of antibiotic clinical trials, and minimize participant burden, as cognitive interviewing can be time-intensive. The study was approved by the IRB. Participants were compensated $50 for completion of the ~2-hour data collection activities (ie, consent, survey administration, cognitive interview).

Figure 2.

Participant flow diagram. This process was completed iteratively in various rounds. aA total of 5 data pulls were completed for the purpose of the study. Date range: 9/16/2019–2/19/2020. bChart review included the following considerations: cPurposeful sampling method was used to prioritize patients while maximizing the possible range of experiences, ages, genders, and clinical representation and severity of infections. dPatients declined participation for the following reasons: not interested (6), dementia/couldn’t understand us (2), didn’t recall having a bloodstream infection (2), in hospice (1). ePassive refusal is defined as when the interviewer was able to make contact with a patient for the screening call but wasn’t able to follow through with completing the screener (or scheduling) due to the patient not answering again after the initial contact. fPatients exceeded the 6–12-week window due to rescheduling requests.

Measure Selection

Using the information obtained in our previous Phase 1 concept elicitation work [3] and in line with guidance [8, 9, 10], we first selected short forms/measures from Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to measure different HRQoL domains (Figure 1). See Supplementary Appendix 1 for the initial survey and second version. We chose PROMIS, including measures and items contained therein, as the starting point because it is comprehensive, validated in a variety of conditions and sociodemographically diverse samples, widely used in research and clinical settings, publicly available, and has multiple formats and translations.

Cognitive Interviewing Procedures

To determine whether PROMIS measures were “fit for purpose,” we conducted a type of individual interview technique called cognitive interviewing [11]. We conducted cognitive interviewing iteratively (Figure 1); that is, we conducted round 1, reviewed findings, and refined the survey and cognitive interview guide/procedures, and then conducted another round (2) of cognitive interviews with different participants. We used this technique to evaluate and ultimately refine the survey by exploring patients’ understanding of items as well as how they constructed and selected answers using a strategy called “think aloud,” which involves asking patients what they are thinking about when responding to and answering the items. Specifically, participants completed the survey, then the interviewer asked some introductory questions regarding their overall impression of the survey and their experience taking it, followed by basic probes applicable to all individual items, including what they thought each item was asking, how it represented their experience, and how they chose/decided on an answer. The interviewer also asked additional item- and domain (ie, measure, construct)-specific (round 2) questions. See Supplementary Appendix 2, which includes the cognitive interviewing guide by round including the questions and probes. The interviewer referred to participants’ survey responses during the interview. Participants who completed the interview via phone received a copy of the survey in advance via mail or e-mail per patient preference. Each cognitive interview was audio-recorded to supplement our detailed notes and facilitate analysis. Interviews were conducted either in-person or via telephone (to maximize participation) by 2 of the team members (K.G., J.M.) under supervision of the first author (H.K.) from 11/11/2019 to 3/12/2020.

Analytic Approach

Three team members used the matrix method [12] to analyze cognitive interview data, meaning that after completing each round of interviews, all notes taken during each interview were entered into Microsoft Excel. Two team members (J.M., K.R.) independently read all entries and wrote summaries across questions/probes and overall. Each summary included consideration of 1 or more of the following parts: comprehension, retrieval, judgment, reaction, and concepts elicited. In particular, the team members explored potential issues such as awkward or ambiguous wording of items, variability in interpretation, inadequate or unnecessary response options, need for more or fewer items/measures, ease of recall of information needed to respond, and fit with personal bloodstream infection–related experiences. Then, these same team members came to consensus, resolving any discrepancies, followed by discussion with the first author and finally the larger research team. After each round of cognitive interviews, members of the team met to review issues raised and consider possible revisions of both the cognitive interview guide and survey. Significant changes to the survey were evaluated in the subsequent round of cognitive interviews. Differences were documented across rounds and reasons for changes made.

Data Storage, Security, and Confidentiality

We collected demographic and clinical information through the electronic medical chart reviews and the Duke Bloodstream Infections Registry. Cognitive interviews were recorded and were used to supplement the notes of the interviewer. We later contacted patients who had completed the cognitive interview via phone to obtain their education information (11th grade or less through to higher education degrees).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

We included 17 SAB and GNB patients across 2 rounds (n = 10 first round, n = 7 second round) of cognitive interviews (Figure 2, Table 1). Across both rounds, the total sample had an average age of ~63 years and included 9 females and 16 White participants with a range in level of education and bloodstream infection characteristics across 7 SAB and 10 GNB patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants in Rounds 1 and 2 of Cognitive Interviews

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 10 | n = 7 | n = 17 | |

| Characteristics | |||

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Male | 5 | 3 | 8 (47.1) |

| Female | 5 | 4 | 9 (52.9) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 65.1 (13.0) | 59.3 (12.1) | 62.7 (12.6) |

| Race, No. (%) | |||

| White | 9 | 7 | 16 (94.1) |

| African American | 1 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Education, No. (%) | |||

| High school diploma or GED | 2 | 0 | 2 (11.8) |

| Some college or technical school training | 3 | 4 | 7 (41.2) |

| College degree (BA or BS) | 3 | 0 | 3 (17.6) |

| Master’s or doctorate/medical/law degree | 1 | 2 | 3 (17.6) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 2 (11.8) |

| Source of bacteremia, No. (%) | |||

| Urinary tract | 5 | 0 | 5 (29.4) |

| Skin and soft tissue | 4 | 2 | 6 (35.3) |

| Biliary tract | 1 | 1 | 2 (11.8) |

| GI translocation | 0 | 1 | 1 (5.9) |

| Hardware | 0 | 1 | 1 (5.9) |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 | 2 (11.8) |

| Bacteria type, No. (%) | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 4 | 3 | 7 (41.2) |

| Methicillin-resistant | 1 | 1 | 2 (11.8) |

| Metastatic sites of infectiona | 1 | 1 | 2 (11.8) |

| Duration of bacteremia >3 d | 1 | 1 | 2 (11.8) |

| Gram-negative | 6 | 4 | 10 (58.8) |

| Escherichia coli | 5 | 2 | 7 (70.0) |

| Klebsiella spp. | 1 | 1 | 2 (20.0) |

| Salmonella litchfield | 0 | 1 | 1 (10.0) |

| ESBL-producing | 1 | 1 | 2 (11.8) |

| Pitt Bacteremia score, median (range) | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 (1–2) | 2 (2–2) | 2 (1–2) |

| Gram-negative | 2 (0–3) | 0 (0) | 0.5 (0–3) |

| Hospital length of stay, median (range), d | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 10.5 (7–46) | 13 (7–16) | 12 (7–46) |

| Gram-negative | 4.5 (2–8) | 5.5 (4–9) | 5 (2–9) |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy, median (range), d | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 35 (15–51) | 42 (28–42) | 42 (15–51) |

| Gram-negative | 7 (7–14) | 14 (7–28) | 8.5 (7–28) |

Abbreviations: ESBL, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase; GI, gastrointestinal.

Included orthopedic hardware infections (n = 2), mediastinitis (n = 1), and epidural and psoas abscesses (n = 1).

Assessment of Survey: 2 Rounds of Cognitive Interviews

The average cognitive interview time was 42 minutes for round 1 and 51 minutes for round 2, not including time to complete the informed consent or survey itself. Supplementary Appendix 3 shows a summary of participant responses by round, with changes between rounds tracked in Supplementary Appendix 4. Based on the first round of cognitive interviews (n = 10), we established participants’ comprehension, retrieval, judgment, and reaction regarding the initial measures. Using this information, we refined our selected measures and items for round 2 of cognitive interviewing (n = 7). We concluded cognitive interviewing after round 2 because additional major (eg, addition/deletion of a measure) changes and evaluation were not necessary. Our final survey is comprised of 10 different PROMIS short forms/measures of the most salient domains reported by patients, as shown in Table 2. These measures include global health, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain intensity, sleep disturbance, depression, anxiety, cognitive abilities, physical functioning, and ability to participate in social roles and activities, as well as 2 adapted items on general/global health and quality of life due to their bloodstream infection (41 items total). Table 3 presents exemplar results from the social domain of HRQoL.

Table 2.

Final HRQoL Survey for Patients with Bloodstream Infection and Link to PROMIS

| Please respond to each item by marking one box per row. | |||||||

| Global (PROMIS Scale v1.2 – Global Health) | Excellent | Very Good | Good | Fair | Poor | ||

| Global01 | 1 | In general, would you say your health is: | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| Global02 | 2 | In general, would you say your quality of life is: | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| Thinking of your bloodstream infection, please answer the following questions to best capture your experiences. | |||||||

| Fatigue (PROMIS Item Bank v1.0 –Fatigue – Short Form 4a) | Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Quite a bit | Very much | ||

| HI7 | 3 | During the past 7 days, I feel fatigued | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| AN3 | 4 | During the past 7 days, I have trouble starting things because I am tired | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| FATEXP41 | 5 | In the past 7 days, how run-down did you feel on average? | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| FATEXP40 | 6 | In the past 7 days, how fatigued were you on average? | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| Gastrointestinal Nausea and Vomiting (PROMIS Scale v1.0 – Gastrointestinal Nausea and Vomiting 4a) | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always | ||

| GISX49 | 7 | In the past 7 days, how often did you have nausea—that is, a feeling like you could vomit? (If never, skip to 9) | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| GISX52 | 8 | In the past 7 days, how often did you know that you would have nausea before it happened? | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| GISX55 | 9 | In the past 7 days, how often did you have a poor appetite? | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| Never | One day | 2-6 days | Once a day | More than once a day | |||

| GISX59 | 10 | In the past 7 days, how often did you throw up or vomit? | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| Pain Intensity (PROMIS Item Bank v.1.0 – Pain Intensity – Scale) | Had no pain | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Very severe | ||

| PAINQU6 | 11 | In the past 7 days, how intense was your pain at its worst? | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| PAINQU8 | 12 | In the past 7 days, how intense was your average pain? | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| No pain | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Very severe | |||

| PAINQU21 | 13 | What is your level of pain right now? | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| Sleep Disturbance (PROMIS Item Bank v1.0 –Sleep Disturbance – Short Form 4a) | Very poor | Poor | Fair | Good | Very Good | ||

| Sleep109 | 14 | In the past 7 days, my sleep quality was | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Quite a bit | Very much | |||

| Sleep116 | 15 | In the past 7 days, my sleep was refreshing | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| Sleep20 | 16 | In the past 7 days, I had a problem with my sleep | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| Sleep44 | 17 | In the past 7 days, I had difficulty falling asleep | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| Emotional Distress – Depression (PROMIS Item Bank v1.0 – Emotional Distress-Depression – Short Form 4a) | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always | ||

| EDDEP04 | 18 | In the past 7 days, I felt worthless | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| EDDEP06 | 19 | In the past 7 days, I felt helpless | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| EDDEP29 | 20 | In the past 7 days, I felt depressed | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| EDDEP41 | 21 | In the past 7 days, I felt hopeless | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| Emotional Distress – Anxiety (PROMIS Item Bank v1.0-Emotional Distress-Anxiety – Short Form 4a) | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always | ||

| EDANX01 | 22 | In the past 7 days, I felt fearful | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| EDANX40 | 23 | In the past 7 days, I found it hard to focus on anything other than my anxiety | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| EDANX41 | 24 | In the past 7 days, my worries overwhelmed me | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| EDANX53 | 25 | In the past 7 days, I felt uneasy | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| Cognitive Function – Abilities (PROMIS Item Bank v2.0 – Cognitive Function - Abilities Subset—Short Form 4a) | Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Quite a bit | Very much | ||

| PC43_2r | 26 | In the past 7 days, my mind has been as sharp as usual | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| PC44_2r | 27 | In the past 7 days, my memory has been as good as usual | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| PC45_2r | 28 | In the past 7 days, my thinking has been as fast as usual | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| PC47_2r | 29 | In the past 7 days, I have been able to keep track of what I am doing, even if I am interrupted | ☐ 1 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 5 |

| Physical Function (PROMIS Item Bank v2.0 – Physical Function – Short Form 6b) | Without any difficulty | With a little difficulty | With some difficulty | With much difficulty | Unable to do | ||

| PFA11 | 30 | Are you able to do chores such as vacuuming or yard work? | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| PFA21 | 31 | Are you able to go up and down stairs at a normal pace? | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| PFA23 | 32 | Are you able to go for a walk of at least 15 minutes? | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| PFA53 | 33 | Are you able to run errands and shop? | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| Not at all | Very little | Somewhat | Quite a lot | Cannot do | |||

| PFC12 | 34 | Does your health now limit you in doing two hours of physical labor? | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| PFB1 | 35 | Does your health now limit you in doing moderate work around the house like vacuuming, sweeping floors or carrying in groceries? | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities (PROMIS Item Bank v2.0 - Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities- Short Form 4a) | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always | ||

| SRPPER11_CaPS | 36 | I have trouble doing all of my regular leisure activities with others | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| SRPPER18_CaPS | 37 | I have trouble doing all of the family activities that I want to do | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| SRPPER23_CaPS | 38 | I have trouble doing all of my usual work (include work at home) | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| SRPPER46_CaPS | 39 | I have trouble doing all of the activities with friends that I want to do | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

| Adapted from Global Health | Excellent | Very Good | Good | Fair | Poor | ||

| 40 | Because of your bloodstream infection, would you say your health is... | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

|

| 41 | Because of your bloodstream infection, would you say your quality of life is... | ☐ 5 |

☐ 4 |

☐ 3 |

☐ 2 |

☐ 1 |

|

Abbreviations: HRQoL, health-related quality of life; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Table 3.

Exemplar Results From Social Domain of HRQoL

| Round 1 | Changes | Round 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure/Items | Cognitive Interview Probes | Summary of Findings | Measure/Items | Cognitive Interview Probes | Summary of Findings | |

| 3 items indicating current level of confidence on a 5-point scale from “I am not at all confident” to “I am very confident.” I can stay involved in community or religious activities. (SEMSS001) I can stay in touch with friends and family. (SEMSS005) I can maintain my usual activities. (SEMSS004) |

-\tWhat time period were you thinking about as you answered these questions? -\tWhen you read the response options here, how do you interpret “level of confidence”? |

“Current” time frame was differentially interpreted, and variation over time was reported. “Level of confidence” language and/or corresponding response options were difficult and/or differentially interpreted. |

Replaced 3 items with PROMIS Item Bank, v2.0—Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities—Short Form 4a (also includes work). The prior items were also determined by study team to not align with measurement goals. Cognitive interview probes were revised. |

Response options: Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always. I have trouble doing all of my regular leisure activities with others. I have trouble doing all of the family activities that I want to do. I have trouble doing all of my usual work (including work at home). I have trouble doing all of the activities with friends that I want to do. |

Basic Probes—Applicable for All (Individual) Items

-\tIn your own words, what do you think this question is asking? -\tHow does this question represent your experience (X)? -\tCan you walk me through how you chose/decided on your answer? -\tI noticed you chose [response category]. Tell me a bit about that. What would have made it [lower category] or [higher adjacent category]? -\tTell me about your choice of ANSWER and not ANSWER (+/-1). -\tWas there anything you weren’t sure whether to include or not include? -\tHow sure are you of your answer? -\tHow difficult or easy was it for you to come up with an answer? Domain-Specific Probes -\tWould your answers be different if you were asked these questions closer to the time of your bloodstream infection? If yes, which questions and how would you have responded differently? (Record response.) -\tWhen do you recall the bloodstream infection impacting you the most in terms of your ability to participate in social roles and activities? |

Patients generally indicated lack of social activities due to infection—mostly after but also during. Short Form Measure and items contained therein are “fit for purpose.” |

Abbreviation: HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

DISCUSSION

The impact of bloodstream infections on patients’ HRQoL is largely unknown. Following best practices for measure development, we generated an HRQoL survey that captures what matters most to patients as they recover from this potentially lethal infection. After 2 rounds of cognitive interviews to evaluate and refine the survey, we found that a compilation of 10 existing PROMIS measures (plus 2 adapted bloodstream-specific items) performed well. In sum, we ultimately developed a survey that was understandable and appropriately captured HRQoL in patients who have had bloodstream infections. This survey can now be used and further investigated in clinical trials and in patient care.

Historically, clinical trials of antibacterial agents have relied upon investigator assessment of success and have largely neglected the patient perspective. Incorporating the patient experience is critical to improve our understanding of the potential benefits and harms of new treatments. The FDA has requested that HRQoL be incorporated as a secondary or exploratory outcome in prescription drug trials [13]. The current investigation directly responds to this request by identifying a combination of PROMIS measures that can serve as key HRQoL end points for bloodstream infection. Our HRQoL end point is particularly robust as the PROMIS measures have already been psychometrically validated in other populations for use in clinical and research settings [14–18]. Although PROs are more commonly used in other medical specialties (eg, cancer) in research and clinical settings, they are newer to the field of bacterial infections perhaps due to their subacute/acute nature, and almost unprecedented in the area of bloodstream infections. Future directions include (1) broad quantitative, psychometric validation of the survey in a representative and diverse population-based sample of SAB/GNB patients, including repeated assessments to capture changes in HRQoL over time; (2) examination of the role of infection severity or specific infectious complications; and (3) attention to additional characteristics of the individual and environment that may not be addressed by PROMIS. In addition, we are extending this work through the ARLG QoL Task Force (under the Innovations Working Group) to complicated urinary tract infection (cUTI), acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection (ABSSSI), hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (HAPB/VABP), and intra-abdominal infection (IAI) [19].

This study had a number of strengths. Our process was rigorous and conducted in accordance with FDA guidance [8], for example, using multiple interviewers and analysts with methodological and clinical expertise. There is growing consensus that supports the use of major guidance documents like the FDA’s guidance to inform PRO selection for clinical trials [20], and therefore we aligned our findings with well-established, reliable, and valid HRQoL measures across domains identified in Phase 1 and selected and prioritized PROMIS measures. We then subsequently combined these measures into a survey that was evaluated via cognitive interviews. Although the PROMIS measures we selected were originally validated with other conditions, our cognitive interview findings demonstrate that they are content-valid and also capture what matters to survivors of bloodstream infections.

Limitations of our study include the fact that we did not assess other measures aside from PROMIS that capture general HRQoL and/or these specific domains. Future work could explore these other measures in comparison. As mentioned in the introduction, however, there are many advantages of the universal PROMIS measures compared with other general HRQoL measures. At the same time as providing standardization and comparison in and across different conditions, one can select domains, measures, and/or items that are relevant from PROMIS; there is ample opportunity to make selections and changes at multiple levels. As we have done, a survey can be constructed that is tailored based on the condition and participant input. Additionally, it is important to note that the results from the cognitive interviewing (type of qualitative research) are not, nor are they intended to be, generalizable. It is crucial in future quantitative, psychometric validation studies of the HRQoL survey to include diverse patient populations, specifically racial/ethnic, geographical, and socioeconomic representation in addition to inclusion of a range of clinical complications and courses, while also considering similarity to those enrolled in clinical trials.

Incorporating the patient perspective in future trials of bloodstream infections and other infectious diseases will enable more meaningful comparisons and the possibility of discerning important differences between treatments. To meet this need, we have created a compilation of existing PRO measures and adapted items for use in clinical trials of SAB and GNB that are appropriate measures for QoL outcomes and reflective of the patient’s experience.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Karen Staman, Senior Science Writer at CHB Wordsmith and for the Duke University School of Medicine Department of Population Health, for her editorial support on this manuscript.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (award number UM1AI104681). This work was also supported by the Durham Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation (ADAPT; CIN 13-410) at the Durham VA Health Care System.

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, Duke University, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, or the US government.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors included in this manuscript have an association that might pose a conflict of interest. Dr. Holland is a scientific advisory board member for Motif Bio and a consultant for Basilea Pharmaceutica, Genentech, Motif Bio, The Medicines Company, and Theravance. Dr. Doernberg is a consultant for Basilea Pharmaceutica and Genentech. Dr. Bosworth has no direct conflicts of interest with the current work but does report receiving grants to his home institutions from Sanofi, Otsuka, Novo Nordisk, Improved Patient Outcomes, Cover My Meds, Pharma foundation, Proteus, and Boehinger Ingelheim, as well as receiving consulting fees from Sanofi, Abbott, Novartis, NIDYA, and Medscape. Dr. Fowler reports grant/research support to his institution from MedImmune, Cerexa/Forest/Actavis/Allergan, Pfizer, Advanced Liquid Logics, Theravance, Novartis, Cubist/Merck, Medical Biosurfaces, Locus, Affinergy, Contrafect, Karius, Genentech, Regeneron, and Basilea; being a paid consultant for Pfizer, Novartis, Galderma, Novadigm, Durata, Debiopharm, Genentech, Achaogen, Affinium, Medicines Co., Cerexa, Tetraphase, Trius, MedImmune, Bayer, Theravance, Cubist, Basilea, Affinergy, Janssen, xBiotech, Contrafect, Regeneron, Basilea, and Destiny; membership in Merck Co-Chair V710 Vaccine; having received educational fees from Green Cross, Cubist, Cerexa, Durata, Theravance, and Debiopharm; having received royalties from UpToDate; and having a patent pending in Sepsis diagnostics. Dr. Reeve has no direct conflicts of interest with the current work but does serve as a paid consultant for University of Florida, Northwestern University, Higgs Boson, and Regeneron. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Patient consent. Patients who completed the cognitive interview in person provided written informed consent. Those who completed the cognitive interview via phone provided verbal consent before being involved any study activities. The written consent form, the verbal consent script, and the overall design of the study were approved by Duke University’s Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1. Goto M, Al-Hasan MN.. Overall burden of bloodstream infection and nosocomial bloodstream infection in North America and Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013; 19:501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McNamara JF, Righi E, Wright H, et al. . Long-term morbidity and mortality following bloodstream infection: a systematic literature review. J Infect 2018; 77:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. King HA, Doernberg SB, Miller J, et al. . Patients’ experiences with Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative bacterial bloodstream infections: a qualitative descriptive study and concept elicitation phase to inform measurement of patient-reported quality of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:237–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holland TL, Arnold C, FowlerVG, Jr. Clinical management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a review. JAMA 2014; 312:1330–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peleg AY, Hooper DC.. Hospital-acquired infections due to gram-negative bacteria. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1804–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dalager-Pedersen M, Thomsen RW, Schonheyder HC, Nielsen H.. Functional status and quality of life after community-acquired bacteraemia: a matched cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016; 22:78e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McNamara JF, Davis JS.. Measuring the meaningful. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:248–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-Focused Drug Development Guidance Public Workshop: Methods to Identify What is Important to Patients & Select, Develop or Modify Fit-For-Purpose Clinical Outcomes Assessments. US Food and Drug Administration; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. . Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1—eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health 2011; 14:967–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. . Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2—assessing respondent understanding. Value Health 2011; 14:978–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Willis G. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Sage Publications, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res 2002; 12:855–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alonso J, Bartlett SJ, Rose M, et al. . The case for an international Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)) initiative. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013; 11:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carlozzi NE, Goodnight S, Kratz AL, et al. . Validation of Neuro-QoL and PROMIS mental health patient reported outcome measures in persons with Huntington disease. J Huntingtons Dis 2019; 8:467–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen CX, Kroenke K, Stump TE, et al. . Estimating minimally important differences for the PROMIS pain interference scales: results from 3 randomized clinical trials. Pain 2018; 159:775–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garcia SF, Cella D, Clauser SB, et al. . Standardizing patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer clinical trials: a patient-reported outcomes measurement information system initiative. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25:5106–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Izadi Z, Gandrup J, Katz PP, Yazdany J.. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials of SLE: a review. Lupus Sci Med 2018; 5:e000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chambers HF, Evans SR, Patel R, et al. . Antibacterial resistance leadership group 2.0 - back to business. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;. 73:730–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crossnohere NL, Brundage M, Calvert MJ, et al. . International guidance on the selection of patient reported outcome measures in clinical trials: a review. Qual Life Res. 2021; 30:21–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.