Abstract

Purpose

Schizophrenia is a chronic and serious mental disorder characterized by disturbances in thought, perception, and behavior that impair daily functioning and quality of life. Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic medications may improve long-term outcomes over oral medications; however, LAI antipsychotic medications are often only considered as a last resort late in the disease course. This study sought to assess current clinical practice patterns, clinicians’ attitudes, and barriers to the use of LAI antipsychotic medications as well as identify unmet educational needs of psychiatric clinicians in managing patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

A survey was distributed via email to 2330 United States-based clinicians who manage patients with schizophrenia; 379 completed the survey and were included for analysis. The survey included five patient case-based scenarios, with seven decision points. Data were analyzed with qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

Results

Clinicians were most confident in determining when to initiate treatment and least confident in transitioning to injectable therapy or administering injectable therapy. Clinicians cited nonadherence, and not wanting to take daily medicine or the “hassle” of frequent treatment, as key factors for which patients were most suitable for an LAI antipsychotic medication. Patient nonadherence was considered the most important barrier to optimal management of patients with schizophrenia. A clinician’s perception of relapse was a strong driver of whether or not the clinician would discuss/recommend an LAI antipsychotic medication.

Conclusion

This study suggests that clinicians may be reluctant to discuss or recommend switching patients to an LAI antipsychotic medication if they are perceived as doing well on current therapy. These results will inform future research and continuing education that aims to improve the confidence, knowledge, and competence of clinicians who provide care for patients with schizophrenia who may benefit from treatment with an LAI antipsychotic medication and clinicians who may be more likely to routinely offer an LAI antipsychotic medication to their patients.

Keywords: long-acting antipsychotic medication, depot, injectable, long-acting, barriers, unmet needs

Plain Language Summary

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic medications can help prevent relapses and hospitalizations in patients with schizophrenia by improving patient adherence to treatment. Despite these benefits, some health-care providers—including doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants—consider LAI antipsychotic medications to be a last resort for patients. This study aimed to understand how health-care providers choose treatments for patients with schizophrenia and identify information gaps where additional education about LAI antipsychotic medications may be helpful.

Three hundred seventy-nine health-care providers completed a survey about confidence in treating patients, attitudes toward available treatments, and barriers to using LAI antipsychotic medications.

While most health-care providers were confident about knowing when to start treatment for schizophrenia, they were less confident about switching a patient from oral to LAI antipsychotic medication. They were also less confident about giving the injection to a patient. Health-care providers preferred using LAI antipsychotic medications in patients who wanted them, had trouble taking their oral medication as directed, or were at risk of relapse. Barriers to using LAI antipsychotic medications included the view that they are high cost, fear of needles, and problems with storing medication.

Education for health-care providers should focus on how LAI antipsychotic medications can prevent relapses and hospitalizations in patients with schizophrenia. Additional information on how to give LAI antipsychotic medications and when to switch from an oral medication to an LAI antipsychotic medication could help build health-care provider confidence in using LAI antipsychotic medications when treating patients with schizophrenia.

Introduction

The use of long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic medications may simplify medication regimens, thereby facilitating adherence in patients with schizophrenia.1 This is an important consideration because partial or nonadherence is frequently encountered and is a common reason for relapse and rehospitalization in patients with schizophrenia.2–4 In a meta-analysis, LAI antipsychotic medications showed superiority versus oral antipsychotic medications in preventing hospitalization.5

While LAI antipsychotic medications have traditionally been seen as a niche treatment for a subset of patients who are nonadherent to treatment, relapse frequently, or pose a risk to others, the paradigm has shifted such that some experts now recommend offering LAI antipsychotic medication as a first-line treatment to the majority of patients who will need long-term antipsychotic therapy.6–8 In addition, guidelines now generally also recommend that LAI antipsychotic medications be provided based on patient preference (eg, convenience), and not only because of concerns about nonadherence.9

Despite the potential benefits of LAI antipsychotic medications for many patients with schizophrenia and the broadening recommendations for use, a substantial body of evidence shows that these agents are substantially underused in patients with severe mental disorders—a finding that has been linked to negative attitudes of health-care providers and patients regarding LAI antipsychotic medications.6,10 For the treatment of first-episode psychosis, clinicians often have a conservative attitude toward LAI antipsychotic medication use, which might be attributed to their personal beliefs about patients’ negative perceptions regarding this formulation, limited knowledge and experience, and/or lack of consensus about LAI antipsychotic medication use.11 In an observational study conducted at community mental health centers, analysis of the patterns of communication suggested that psychiatrists presented LAI therapy in a negative light, resulting in a low proportion of patients accepting this therapy.12 In addition, clinicians are sometimes hesitant to treat patients with LAI antipsychotic medications because of their perceptions of the time and costs associated with LAI administration, the belief that only patients who are nonadherent should be treated with LAI antipsychotic medications, and their lack of confidence in the scientific evidence, much of which is not based on real-world use.11

Attitudes may be an especially important predictor of adherence, as illustrated by studies in schizophrenia that incorporate and validate use of the modified Health Belief Model, which posits that adherence to a specific treatment hinges mainly on perceptions of costs and benefits, risk of relapse, and outcome severity.13–16

Research can help better understand practice patterns to determine continuing needs and educational priorities regarding the selection of antipsychotic treatment/formulation for patients with schizophrenia. Toward that end, surveys that include case vignettes can be an effective way to obtain rapid feedback from a broad group of clinicians. Case vignettes are recognized for their utility in predicting health-care provider practice patterns compared with chart review and standardized patient approaches, demonstrating that this can be a valid and comprehensive method to measure processes of care in actual clinical practice. Moreover, case vignettes are cost-effective and perceived by some clinicians as less intrusive than other means of measurement.17–19

Accordingly, we sought to identify unmet needs related to the management of patients with schizophrenia from the perspectives of psychiatric clinicians (including psychiatrists, psychiatric nurse practitioners [NPs], and psychiatric physician assistants [PAs]) using a survey approach that incorporates case-based patient scenarios relevant to current clinical practice.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The survey was developed in collaboration with a schizophrenia topic expert to assess current practice patterns, attitudes, and barriers to use of LAI antipsychotic medications in patients with schizophrenia. Among other questions, the survey included five patient case-based scenarios representing a variety of settings where LAI antipsychotic medications might be considered. Prior to general launch, the survey was reviewed by four practicing psychiatric clinicians to ensure that the cases were clinically accurate and that the questions were being interpreted as intended. Responses were collected via an online survey platform. The survey was reviewed and approved by the sponsor, Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc. Western Institutional Review Board (Puyallup, WA, USA) exempted the research project from institutional review board oversight under the Common Rule 45 CFR § 46.104(d)(2) (the research only included interactions involving survey procedures or interview procedures, and there were adequate provisions to maintain participant privacy and confidentiality). The full survey is provided in Supplemental Table 1.

The survey was distributed via email by CE Outcomes in September 2019 to psychiatrists and psychiatric NPs and PAs practicing in the United States (US). Emails of potential respondents were obtained from commercially available lists as well as an internal database of clinicians who have previously engaged in similar studies and have agreed to being contacted. For inclusion in the analysis, respondents were required to be a specialist in psychiatry, personally seeing at least 1 patient with schizophrenia each month, and personally managing at least 1 patient each week. Duplicate responses were not allowed. Respondents provided informed consent prior to completing the survey and were provided a $50 USD incentive for completing the survey.

A factor analysis was conducted to distill survey questions down to elements that might predict case-based decision-making points (eg, whether participants would or would not discuss LAI antipsychotic medications or recommend switching to an LAI antipsychotic medication). In addition to participant perceptions of relapse potential for each case presentation and demographics, the factors found in survey responses were grouped into nine categories: (1) confidence (eg, confidence in initiating injectable therapy, selecting treatment, transitioning a stable patient from an oral antipsychotic medication to an LAI antipsychotic medication); (2) medical barriers; (3) emerging treatment (eg, familiarity or likelihood to seek out new information); (4) lack of experience with LAI antipsychotic medications; (5) limitations of LAI antipsychotic medications; (6) safety; (7) efficacy; (8) social barriers; and (9) stigma.

Statistical Methods

The survey used a quota approach to data collection. Based on power calculations, 375 or more clinicians were required to respond; the first respondents to complete the survey were included for analysis. A logistic regression modeling approach was used to determine key predictors in the decision to (a) discuss an LAI antipsychotic medication with a patient; and (b) recommend transition of the patient to an LAI antipsychotic medication. Descriptive statistics are provided.

Results

Characteristics of Clinicians

The survey was distributed via email invitation to 2230 clinicians, of which 451 entered the survey. A total of 379 responses from health-care providers, comprising 302 psychiatrists and 77 psychiatric NPs/PAs, met the screening criteria. Compared with psychiatric NPs/PAs, psychiatrists reported seeing more patients per week (mean: 76.3 versus 46.5 patients), and more patients with schizophrenia per month (mean: 45.6 versus 20.9 patients; Table 1). The physician group also reported more years in practice than NPs/PAs (mean: 22.3 versus 13.4 years; Table 1). The proportion of participants who self-reported working in an academic setting was 19% for psychiatrists and 30% for psychiatric NPs/PAs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cliniciansa

| Characteristic | Psychiatrist (n = 302) | Psychiatric NP/PA (n = 77) | Overall (N = 379) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years in psychiatry practice, mean (SD) | 22.3 (9.0) | 13.4 (9.1) | 20.5 (9.7) |

| Patients seen per week, mean (SD) | 76.3 (53.2)b | 46.5 (27.0) | 70.2 (50.4) |

| Patients with schizophrenia seen per month, mean (SD) | 45.6 (40.4)b | 20.9 (27.8) | 40.5 (39.4) |

| Pediatric patients,c % | 17 | 21 | 18 |

| Pediatric patientsc with schizophrenia seen per month, mean (SD) | 5.5 (11.7) | 1.6 (4.1) | 4.7 (10.7) |

| Academic setting, % | 19 | 30 | 21 |

| Certification in child/adolescent psychiatry, % | 25 | 30 | 26 |

| Practice location, % | |||

| Urban | 45 | 48 | 46 |

| Suburban | 45 | 39 | 44 |

| Rural | 10 | 13 | 10 |

| Present employment, % | |||

| Group single-specialty practice | 27 | 22 | 26 |

| Solo practice | 25 | 10 | 22 |

| Academic/university/medical school | 16 | 21 | 17 |

| Group multi-specialty practice | 8 | 12 | 9 |

| Government/military/VA hospital | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| Non-government community hospital | 5 | 9 | 6 |

| Other | 11 | 20 | 13 |

Notes: aTotals may not equal 100% because of rounding; bbased on n=300; cage <18 years.

Abbreviations: NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant; SD, standard deviation; VA, US Department of Veterans Affairs.

Confidence in Schizophrenia Management

Health-care providers who participated in this survey were most confident in determining the right time to begin treatment for schizophrenia, and least confident in transitioning to injectable therapy or administering injectable therapy. Whereas 88% of psychiatrists and 72% of psychiatric NPs/PAs were very confident or extremely confident in determining when to begin treatment, only 64% of psychiatrists and 59% of psychiatric NPs/PAs were very confident or extremely confident in transitioning a stable patient from an oral antipsychotic medication to an LAI antipsychotic medication. Likewise, the proportion of respondents saying they were very confident or extremely confident administering injectable therapy in their practice was 58% for psychiatrists and 61% for psychiatric NPs/PAs.

Patient Case Scenarios: LAI Antipsychotic Medications

The survey included five patient case-based scenarios with a total of seven decision points. Clinicians were asked to rate cases according to specific parameters, such as likelihood of relapse, their willingness to recommend LAIs, and their willingness to prescribe LAI antipsychotic medications. The cases are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient Cases Included in Clinician Survey

| Case Number | Summary | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | • Recently diagnosed • Treatment-naïve |

A 23-year-old man, inpatient in a psychiatric unit, recently admitted because of agitation associated with hallucinations and delusions. First experienced psychotic symptoms 2 months ago but became progressively worse and functioning is grossly impaired. Awareness when distressed, treatment-naïve. |

| Case 1 (continued) | • Discharged with oral medication • Marked improvement at follow-up |

He is discharged on oral antipsychotic medication with instructions to follow up at the Community Mental Health Center. At a follow-up visit 3 months later, he has had marked improvement in the severity of his symptoms. He is able to focus his attention elsewhere during hallucinations. There are no signs of sedation or other adverse effects. |

| Case 2 | • Recent relapse due to nonadherence • Low social support network |

A 35-year-old woman with a 10-year history of schizophrenia. Six months ago, she was hospitalized because of paranoid delusions after forgetting to pick up a refill of her oral antipsychotic medication. Stabilized on an oral antipsychotic while hospitalized and continued on this treatment following discharge. Low/no social support. She presents 2 months post-discharge, states she is taking her medication, doing well, and denies any symptoms. |

| Case 3 | • Long schizophrenia history • Multiple relapses • Potential future adherence issues |

A 50-year-old woman with 15-year history of schizophrenia. Previously functioning well on oral antipsychotic medication, has a history of multiple relapses. Recently hospitalized because of an exacerbation of unrelated acute bronchitis, for which she was prescribed multiple other oral medications. She reports some difficulty in remembering to take all her medications. |

| Case 4 | • Younger patient • Functioning well on oral medications |

A 16-year-old high school junior with schizophrenia diagnosed 6 months ago is functioning reasonably well on oral antipsychotic medication. She also is on 2–3 other oral medications. |

| Case 5 | • New environment • Patient would rather not take oral medication |

A 30-year-old man who recently returned to college after a 7-year hiatus because of poorly controlled symptoms. On an oral antipsychotic medication regimen that has helped him function better. He states that he consistently takes his medication. He wonders if he will ever be able to stop taking medications and tells you he does not want this “daily reminder” that he is chronically mentally ill. |

| Case 5 (continued) | • Hospitalization due to relapse • Family member reports medication nonadherence |

You decide not to alter his medication at this point. One month later, he is hospitalized because of a relapse in which he was experiencing hallucinations, delusions, and disordered thinking, which were severely interfering with daily functioning and leading to failing grades. A family member reports that he is inconsistent in taking his medication, despite their efforts to assist with this. |

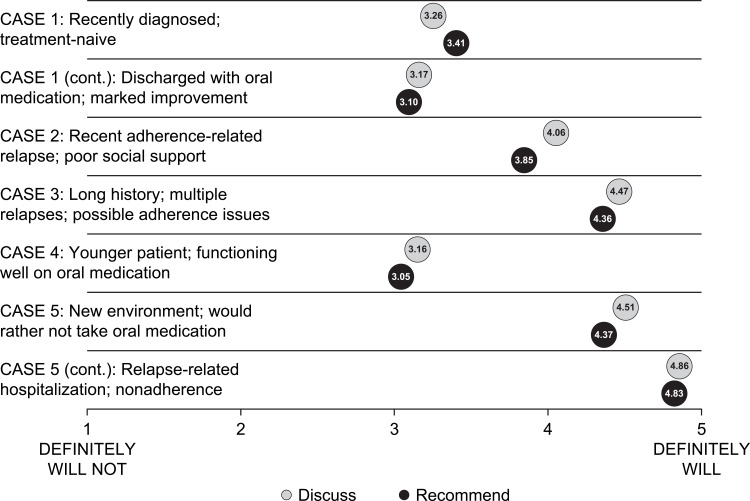

Overall, the likelihood that respondents would discuss or recommend switching to an LAI antipsychotic medication varied according to the patient scenario (Figure 1). Respondents were most likely to discuss (mean score: 4.51 on a 5-point Likert scale) and recommend (mean score: 4.37) switching to an LAI antipsychotic medication for Case 5 (patient in a new environment who would rather not take oral medications); in the continuation of that case, which included hospitalization due to relapse and patient nonadherence to oral medication, the likelihood increased even further, to a mean score of 4.86 to discuss and 4.83 to recommend switching to an LAI antipsychotic medication. By contrast, respondents were considerably less likely to discuss (mean score: 3.16) and recommend (mean score: 3.05) switching to an LAI antipsychotic medication for Case 4 (the younger patient who was perceived to be functioning well on oral medications).

Figure 1.

Likelihood to discuss or recommend switching to an LAI antipsychotic medication.a

Note: aSurvey included definitions for hallucinations, delusions, disorganized behavior, and thought disorder.

Abbreviation: LAI, long-acting injectable.

Discussing and Recommending LAI Antipsychotic Medications in Different Scenarios: Psychiatrists versus Psychiatric NPs/PAs

The likelihood of discussing or recommending LAI antipsychotic medications for individual cases was generally consistent between psychiatrists and psychiatric NPs/PAs, although some differences were noted (Supplemental Table 2). For Case 1 (recently diagnosed and treatment-naive patient), 46% of psychiatrists and 50% of psychiatric NPs/PAs said they would probably or definitely discuss LAI antipsychotic medications with the patient, whereas 46% of psychiatrists and 60% of psychiatric NPs/PAs said they would probably or definitely recommend the transition to an LAI antipsychotic medication. For Case 2 (patient with recent adherence-related relapse and poor social support), a larger proportion of psychiatric NPs/PAs than psychiatrists said they would probably or definitely discuss LAI antipsychotic medications with the patient (93% versus 77%), although the gap was somewhat less pronounced between the groups when asked if they would probably or definitely recommend the transition (78% versus 67%). For Case 3 (patient with long history of schizophrenia, multiple relapses, and possible adherence issues), a similarly high proportion of psychiatrists and psychiatric NPs/PAs said they would probably or definitely discuss LAI antipsychotic medications with the patient (92% and 95%, respectively), and would probably or definitely recommend the transition to an LAI antipsychotic medication (90% and 89%, respectively). Likewise, in Case 5 (patient in a new environment who would rather not take oral medications), nearly all psychiatrists and psychiatric NPs/PAs (91% and 98%, respectively) would probably or definitely discuss LAI antipsychotic medications, and a similarly high proportion (86% and 88%, respectively) would probably or definitely recommend the transition to an LAI antipsychotic medication. By contrast, in Case 4 (younger patient functioning well on oral medications), fewer psychiatrists and psychiatric NPs/PAs said they would probably or definitely discuss LAI antipsychotic medications (38% and 39%, respectively) or recommend transitioning to an LAI antipsychotic medication (31% and 30%, respectively).

Clinician Perceptions of Relapse: Psychiatrists versus Psychiatric NPs/PAs

For cases in which the question was relevant (ie, all cases except for Case 1, the recently diagnosed patient), respondents were asked to rate the likelihood of relapse (Supplemental Table 3). For Case 2 (patient with recent adherence-related relapse and poor social support), 56% of psychiatrists and 64% of psychiatric NPs/PAs said that the patient would probably or definitely relapse if continued on the same treatment regimen. By contrast, nearly all psychiatrists and psychiatric NPs/PAs (91% and 93%, respectively) felt that the patient in Case 3 (patient with long history of schizophrenia, multiple relapses, and possible adherence issues) would probably or definitely relapse on the same regimen. Only 42% of psychiatrists and 39% of psychiatric NPs/PAs said that Case 4 (younger patient functioning well on oral medications) would probably or definitely relapse, while for Case 5 (patient in a new environment who would rather not take oral medications), about three-quarters of respondents (74% and 72%, respectively) thought a relapse would probably or definitely occur.

Suitability for LAI Antipsychotic Medications: Provider Perceptions

When asked what types of patients are most suited for an LAI antipsychotic medication, respondents cited a number of factors, including nonadherence (despite functioning well on oral medication when taken as directed); not wanting to take daily medicine or not wanting the “hassle” of frequent treatment; younger patients with early relapses or older patients with multiple relapses; patients who are forgetful or have poor insight into their disease; patients with comorbidities, cognitive deficits, or poor function; patients with poor support system or poor housing; and patients who are agreeable to treatment with an LAI antipsychotic medication (data not shown). Conversely, the types of patients that respondents found least suitable for an LAI antipsychotic medication included patients who are adherent, stable, and have schizophrenia that is well controlled with oral medication; younger patients; patients with few or no hospitalizations; patients with insight into their disease and social support; and patients who fear needles or are unwilling to receive an injectable medication (data not shown).

Attitudes Toward LAI Antipsychotic Medication Use, Adherence, and Stigmatization

Adherence was an important factor in the decision to use LAI antipsychotic medications among respondents to this survey. The majority of respondents (86% of psychiatrists and 81% of psychiatric NPs/PAs) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that LAI antipsychotic medications are primarily used in patients with adherence concerns; moreover, 52% of psychiatrists and 42% of psychiatric NPs/PAs agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that most patients on oral antipsychotic medication for schizophrenia will eventually have adherence issues (Table 3). By contrast, severity of symptoms appeared to play a lesser role is the decision to use LAI antipsychotic medications compared with adherence, with only 35% of psychiatrists and 27% of psychiatric NPs/PAs agreeing or strongly agreeing that LAI antipsychotic medications should be reserved for patients with more severe symptoms (Table 3). Few respondents (14% of psychiatrists and 8% of psychiatric NPs/PAs) agreed or strongly agreed that they had concerns of stigmatization when they prescribe an LAI antipsychotic medication for a patient with schizophrenia (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinician Attitude Related to Management of Patients with Schizophreniaa

| Please Rate Your Level of Agreement with the Following Statements About Your Typical Patient with Schizophrenia. | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatrist (n = 302) | Psychiatric NP/PA (n = 77) | Overall (N = 379) | |

| LAI antipsychotics are saved for patients with more severe symptoms | |||

| Strongly disagree | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Disagree | 32 | 44 | 34 |

| Neutral | 26 | 22 | 25 |

| Agree | 29 | 22 | 28 |

| Strongly agree | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| I primarily use LAIs in my patients with adherence concerns | |||

| Strongly disagree | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Disagree | 5 | 8 | 6 |

| Neutral | 8 | 12 | 9 |

| Agree | 52 | 46 | 51 |

| Strongly agree | 34 | 35 | 34 |

| I have concerns of stigmatization when I diagnose an individual with schizophrenia | |||

| Strongly disagree | 10 | 14 | 11 |

| Disagree | 22 | 18 | 21 |

| Neutral | 26 | 17 | 24 |

| Agree | 33 | 38 | 34 |

| Strongly agree | 10 | 13 | 10 |

| I have concerns of stigmatization when I prescribe an LAI for a patient with schizophrenia | |||

| Strongly disagree | 23 | 27 | 24 |

| Disagree | 40 | 43 | 41 |

| Neutral | 23 | 22 | 22 |

| Agree | 10 | 5 | 9 |

| Strongly agree | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Most patients on oral antipsychotic medication for schizophrenia will eventually have adherence issues | |||

| Strongly disagree | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Disagree | 17 | 25 | 19 |

| Neutral | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Agree | 39 | 29 | 37 |

| Strongly agree | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| LAI antipsychotics are as safe as other medications for schizophrenia management | |||

| Strongly disagree | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Disagree | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Neutral | 14 | 10 | 13 |

| Agree | 45 | 43 | 45 |

| Strongly agree | 38 | 44 | 39 |

| Patients are able to tolerate LAI antipsychotics as much as other medications for schizophrenia management | |||

| Strongly disagree | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Disagree | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Neutral | 14 | 8 | 13 |

| Agree | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| Strongly agree | 35 | 39 | 36 |

| Patients on LAIs have more severe symptoms than patients on other medications | |||

| Strongly disagree | 6 | 14 | 8 |

| Disagree | 30 | 36 | 31 |

| Neutral | 31 | 34 | 31 |

| Agree | 26 | 12 | 23 |

| Strongly agree | 7 | 4 | 6 |

| LAIs have similar efficacy as other medications to stabilize disease | |||

| Strongly disagree | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Disagree | 5 | 9 | 6 |

| Neutral | 15 | 8 | 14 |

| Agree | 55 | 57 | 56 |

| Strongly agree | 24 | 26 | 24 |

| LAIs have similar efficacy as other medications to prevent relapse | |||

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Disagree | 14 | 10 | 13 |

| Neutral | 10 | 12 | 10 |

| Agree | 44 | 49 | 45 |

| Strongly agree | 30 | 27 | 29 |

Note: aTotals may not equal 100% because of rounding.

Abbreviations: LAI, long-acting injectable; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant.

Perceptions of LAI Antipsychotic Medication Efficacy, Tolerance, and Safety

Eighty-three percent of psychiatrists and 87% of psychiatric NPs/PAs agreed or strongly agreed that LAI antipsychotic medications are as safe as other medications in the management of schizophrenia, whereas 83% of psychiatrists and 87% of psychiatric NPs/PAs agreed or strongly agreed that patients are able to tolerate LAI antipsychotic medications as much as other medications in schizophrenia management (Table 3). High proportions of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that LAIs have similar efficacy to other medications to stabilize disease (79% of psychiatrists and 83% of psychiatric NPs/PAs) and to prevent relapse (74% and 76%, respectively), whereas very few agreed or strongly agreed that patients taking LAI antipsychotic medications have more severe symptoms compared with those on other medications (33% and 16%, respectively).

Clinician Use of LAI Antipsychotic Medications for Patients with Schizophrenia

When transitioning from an oral to an LAI antipsychotic medication for a patient with schizophrenia, the majority of clinicians (56% of psychiatrists and 51% of psychiatric NPs/PAs) said they “mostly” stay with the same molecule (ie, the LAI formulation of the same medication). A substantial proportion of psychiatrists and psychiatric NPs/PAs (34% and 40%, respectively) said the decision to stay or switch to a different molecule depends on the patient, while about 1 in 10 (8% and 9%, respectively) said they always stay with the same molecule.

Barriers to Optimal Care of Schizophrenia and LAI Antipsychotic Medications

Patient nonadherence was cited as the most important barrier to optimal management of patients with schizophrenia; on a scale of 1 (low) to 5 (high), the mean score for the importance of patient nonadherence was 4.5 for psychiatrists and 4.6 for psychiatric NPs/PAs. Other barriers to optimal management reported by participants included medication side effects (mean score: 4.1 for both psychiatrists and psychiatric NPs/PAs), lack of social support (mean score: 4.0 and 4.1, respectively), and lack of coordination of care (mean score: 3.9 and 4.0).

The highest-rated barriers specific to use of LAI antipsychotic medications reported by psychiatrists and psychiatric NPs/PAs included patient aversion to needles (mean score: 3.4 and 3.3, respectively), increased cost compared with oral medications (mean score: 3.3 and 3.4, respectively), and logistical issues (such as lack of medication storage; mean score: 3.2 and 3.4, respectively). By contrast, lower scores were seen for lack of experience prescribing injectable treatment (mean score: 2.3 and 2.6, respectively) and limited comfort in discussing advantages and disadvantages of LAI antipsychotic medications with patients (mean score: 2.2 and 2.4, respectively). When asked to specify other barriers they have experienced related to use of LAI antipsychotic medications in their patients with schizophrenia, about one-third of participants (33%) who responded said insurance issues represented a barrier, while 12% cited patient perception (eg, less control, perception that they are more ill than others, equating newer medications with side effects of older medications), 11% cited administration issues, and 6% cited availability (including limited LAI antipsychotic treatment choices).

Predicting the Transition to LAI Antipsychotic Medications: Regression Modeling

Results of the factor analysis indicated that a clinician’s perception of relapse was a strong driver of whether or not the clinician would discuss or recommend an LAI antipsychotic medication. In patient case scenarios where potential for relapse was considered (ie, all cases except for Case 1, the recently diagnosed patient), participants who believed the patient to be at risk of relapse were 9 times as likely to discuss or recommend an LAI antipsychotic medication. Conversely, confidence in initiating a conversation related to transitioning from an oral medication was significantly associated with likelihood of discussing and recommending an LAI antipsychotic medication in Case 1, as well as in Case 4. Clinician likelihood to seek out information on new or emerging treatments, perceptions of LAI antipsychotic medication safety, provider patient load, and availability of support staff were also significantly associated with the likelihood of discussing and/or transitioning to an LAI antipsychotic medication. By contrast, lack of experience with LAI antipsychotic medications and negative perceptions about LAI antipsychotic medications were associated with lower likelihood of discussing and recommending LAI antipsychotic medications (Supplemental Table 4).

New and Emerging Therapies

When asked what topics respondents would find valuable in upcoming continuing education opportunities related to schizophrenia, the number one answer was new and emerging treatments (38% of respondents), followed by initiating/transitioning to LAI antipsychotic medications (13%), and management of side effects (9%). In addition, the majority (59% of psychiatrists and 61% of psychiatric NPs/PAs) indicated they would be very or extremely likely to seek out information on new or emerging schizophrenia therapies.

Discussion

Results of this survey study provide insights into what makes clinicians more likely or less likely to discuss LAI antipsychotic medications as a therapeutic option for patients with schizophrenia and to recommend a transition from an oral antipsychotic medication to an LAI antipsychotic medication. In general, clinicians are reluctant to switch a patient to an LAI antipsychotic medication if the patient is performing well on current therapy. However, when a patient shows a sign of potential adherence issues, the likelihood to use an LAI antipsychotic medication increases. In a related finding, clinicians responding to this survey ranked patient adherence as the top barrier to the management of patients with schizophrenia.

Perception of relapse was shown in this study to be a key predictor of whether or not a health-care provider will discuss or recommend an LAI antipsychotic medication. Of note, participants were 9 times as likely to discuss or recommend an LAI antipsychotic medication for patient case scenarios in which they believed the patient to be at substantial risk of relapse. By contrast, negative attitudes around the limitations of LAI antipsychotic medications are key drivers in the decision not to discuss or recommend these treatments. Safety and efficacy perceptions had a minimal role in predicting LAI antipsychotic medication use in the factor analysis. In general, few clinicians responding to the survey appeared to have concerns about the safety, tolerability, or efficacy of LAI antipsychotic medications in relation to other treatment options.

This analysis also provides insights into clinical practice related to LAI antipsychotic medication use. When switching to an LAI antipsychotic medication, most respondents said they prefer to stay with the same molecule, but few stated that this is always their approach. Clinicians generally seem confident in determining when to start treatment and selecting which treatment is needed, but they are least confident in administering injectable therapy and transitioning a patient from oral to an injectable treatment. In addition, the findings show that clinicians have low familiarity with new and emerging therapies. Given results of the regression analysis, confidence and familiarity with newer therapies may predict use of LAI antipsychotic medications in a patient performing well on oral medication.

Findings from this study indicate that educational initiatives are needed to address the main attitudinal drivers in the health-care provider’s decision to discuss or recommend LAI antipsychotic medications for patients with schizophrenia. Perception of relapse was shown to be one of the main drivers of use of LAI antipsychotic medications in this study, suggesting that continued education related to the potential dangers of relapse and relapse prevention would be useful and may positively impact clinical practice.

Further education is needed related to LAI experience, attitudes, and safety. Clinicians would benefit from increased experience discussing the pros and cons of LAI antipsychotic medications, as well as information about how patients view LAI antipsychotic medications. Educational sessions including the patient's point of view may be valuable. Case-based education could be used to illustrate how LAI antipsychotic medications are used in different patient contexts, which in turn could help clinicians learn about the indications of these injectable formulations and outcomes that might be expected when LAI antipsychotic medications are not reserved for those patients with adherence issues or more severe symptoms. Additional information about the safety and tolerability of LAI antipsychotic medications would also be useful for clinicians.

Specific issues of clinician confidence can be addressed, particularly given that clinicians were least confident in their ability to effectively transition a stable patient from oral medication to an injectable antipsychotic medication, and in their ability to administer injectable therapy in their practice. Additionally, when clinicians were asked what they would find useful in future education, the issue of transition was the second-most common answer. The most common answer was emerging treatment, another area where education is clearly needed, given both high levels of interest in this topic and low familiarity with new and emerging treatments—both of which were shown in this survey.

This study has limitations, primarily that cases were used as a proxy for clinical practice. While case vignettes are a valid and comprehensive method of measuring actual clinical practice,17–20 we recognize that a social-desirability bias may exist to answer questions in a survey based on a perception that one choice will be more favorably viewed than another.21 However, the regression model shows key attitudes that could continue to drive more favorable use of LAI antipsychotic medications. Further, as these data were captured for US-based clinicians, their applicability to global practice could be limited. However, a similar study showed that Switzerland-based clinicians also had deficits in the use of LAI antipsychotic medications in their patients.22 Regional differences in the acceptance of LAI antipsychotic medications have been reported, with regions that prioritize community-based systems of mental health care (eg, United Kingdom) being more proactive in the use LAI antipsychotic medications.11

Additionally, as with most surveys, selection bias was possible because recipients from a particular demographic group and/or who possess a specific set of characteristics may be more likely to respond to the survey. The survey used a quota approach to data collection and only the first respondents that met the screening criteria were included for analysis. This could have presented a selection bias for those psychiatry clinicians particularly interested in schizophrenia management or practice pattern surveys. In addition, although the survey included other questions, responses with a 5-point Likert scale for patient case-based scenarios were unlikely to comprehensively capture the perspective of psychiatric clinicians. In addition, the factor analysis may not have produced a complete set of associated attributes, and since logistic regression modeling only relates independent and dependent variables linearly, it may not fully describe the complex relationships related to the decision to discuss or initiate LAI antipsychotic medication therapy. Lastly, the use of descriptive statistics only allows for the interpretation of those surveyed and cannot be generalized to the complete population of psychiatric clinicians.

This study did not directly address the recommendation in current guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia that suggests LAI antipsychotic medications be provided based on patient preference and not only in instances where adherence is a clinical concern.9 The implication of this recommendation is that LAI antipsychotic medications should be routinely discussed with patients as an alternative to daily medication administration; at this time, this discussion does not appear to take place often enough,21 despite our finding that only few respondents had concerns of stigmatization when they prescribe an LAI antipsychotic medication for a patient with schizophrenia.

Conclusions

Results of this study suggest that while clinicians may be reluctant to recommend switching a patient to an LAI antipsychotic medication if they are performing well on current therapy, adherence issues—seen as the primary barrier to optimal management of patients with schizophrenia—increase the likelihood of discussing or recommending an injectable treatment option. Perception of relapse is a key driver in the choice to discuss LAI antipsychotic medications or recommend switching to an LAI antipsychotic medication, while negative attitudes around the limitations of LAI antipsychotic medications are key drivers in the decision not to discuss or recommend an LAI antipsychotic medication. When switching to an LAI antipsychotic medication, most clinicians prefer to stay with the same molecule, but few state that this is always their approach. Overall, clinicians are satisfied with the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of LAI antipsychotic medications when compared with other medications for schizophrenia management. Results of this study may inform future research and the provision of continuing education that aims to improve the confidence, knowledge, and competence of clinicians who provide care for patients with schizophrenia who may benefit from treatment with an LAI antipsychotic medication. The recommendation in current guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia that suggests LAI antipsychotic medications be provided based on patient preference, and not only in instances where adherence is a clinical concern, will require additional emphasis in any future educational endeavors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc. Professional medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Jennifer DiNieri, PhD, and Brian Haas, PhD, CMPP, of Ashfield MedComms, part of UDG Healthcare PLC, and supported by Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc. The authors take full responsibility for the content of this article.

Abbreviations

CI, confidence interval; LAI, long-acting injectable; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant; SD, standard deviation; US, United States.

Disclosure

EB, GDS: research study support: Teva Pharmaceuticals. LC: consultant: AbbVie, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Axsome Therapeutics, BioXcel Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cadent Therapeutics, Eisai, Impel NeuroPharma, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Karuna, Lundbeck, Luye Pharma Group, Lyndra Therapeutics, Medavante-ProPhase, Merck, Neurocrine Biosciences, Noven, Osmotica Pharmaceutical, Otsuka, Relmada Therapeutics, Sage Therapeutics, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, University of Arizona, and one-off ad hoc consulting for individuals/entities conducting marketing, commercial, or scientific scoping research. Speaker: AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Eisai, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Sage, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and continuing medical education activities organized by medical education companies such as Medscape, NACCME, Neuroscience Education Institute, Vindico Medical Education, and universities and professional organizations/societies. Stocks (small number of shares of common stock): Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Pfizer purchased more than 10 years ago. Royalties: Wiley (Editor-in-Chief, International Journal of Clinical Practice, through end of 2019); UpToDate (reviewer); Springer Healthcare (book); and Elsevier (Topic Editor, Psychiatry, Clinical Therapeutics). MM, MS: employment, stock: Teva Pharmaceuticals. SS: Nothing to disclose. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Sajatovic M, Ross R, Legacy SN, et al. Identifying patients and clinical scenarios for use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics - expert consensus survey part 1. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1463–1474. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S167394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Citrome L. New second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(7):767–783. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2013.811984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Citrome L. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics update: lengthening the dosing interval and expanding the diagnostic indications. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(10):1029–1043. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2017.1371014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Citrome L. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics: what, when, and how. CNS Spectr. 2021;26(2):118–129. doi: 10.1017/S1092852921000249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, Kane JM, Correll CU. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):957–965. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim B, Lee SH, Yang YK, Park JI, Chung YC. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for first-episode schizophrenia: the pros and cons. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2012;2012:560836. doi: 10.1155/2012/560836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llorca PM, Abbar M, Courtet P, Guillaume S, Lancrenon S, Samalin L. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):340. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(suppl 3):1–24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15032su1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(9):868–872. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.177901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samalin L, Charpeaud T, Blanc O, Heres S, Llorca PM. Clinicians’ attitudes toward the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(7):553–559. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31829829c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parellada E, Bioque M. Barriers to the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the management of schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(8):689–701. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0350-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiden PJ, Roma RS, Velligan DI, Alphs L, DiChiara M, Davidson B. The challenge of offering long-acting antipsychotic therapies: a preliminary discourse analysis of psychiatrist recommendations for injectable therapy to patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):684–690. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markowitz MA, Levitan BS, Mohamed AF, et al. Psychiatrists’ judgments about antipsychotic benefit and risk outcomes and formulation in schizophrenia treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(9):1133–1139. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(4):637–651. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.4.637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baloush-Kleinman V, Levine SZ, Roe D, Shnitt D, Weizman A, Poyurovsky M. Adherence to antipsychotic drug treatment in early-episode schizophrenia: a six-month naturalistic follow-up study [published correction appears in Schizophr Res. 2013 May;146(1–3):379]. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1–3):176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sapra M, Vahia IV, Reyes PN, Ramirez P, Cohen CI. Subjective reasons for adherence to psychotropic medication and associated factors among older adults with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;106(2–3):348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luck J, Peabody JW, Lewis BL. An automated scoring algorithm for computerized clinical vignettes: evaluating physician performance against explicit quality criteria. Int J Med Inform. 2006;75(10–11):701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283(13):1715–1722. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, et al. Measuring the quality of physician practice by using clinical vignettes: a prospective validation study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(10):771–780. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peabody JW, Liu A. A cross-national comparison of the quality of clinical care using vignettes. Health Policy Plan. 2007;22(5):294–302. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czm020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landsberger HA. Hawthorne Revisited: Management and the Worker: Its Critics, and Developments in Human Relations in Industry. 1st ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaeger M, Rossler W. Attitudes towards long-acting depot antipsychotics: a survey of patients, relatives and psychiatrists. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(1–2):58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]