Jonathan walked into your consultation room complaining of low back pain with pain running down his right leg for the past two weeks. He had been working from home since Singapore’s circuit breaker measures were introduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. He recently started doing some home-based calisthenics workouts after getting restless from staying at home. He had tried self-medicating with some muscle rub pain relief creams, but the pain persisted.

WHAT IS ACUTE LOW BACK PAIN?

Acute low back pain is defined as pain extending from the lowest rib to the buttocks and sometimes even the lower limbs. The pain is generally felt on either side of the midline. It is acute in nature and typically lasts up to six weeks.(1)

HOW COMMON OR RELEVANT IS THIS TO MY PRACTICE?

Acute low back pain is estimated to affect up to 80% of the adult population in Singapore,(2) leading to significant anxiety and debilitation in patients. It most commonly affects adults aged between 30 and 40 years.(3)

Most low back pain is non-specific, whereby no causes or structures can be identified to account for the patient’s perceived pain. In many patients, the pain is self-limiting and resolves within two weeks with minimal intervention.(4) Apart from back strain due to overactivity, other common causes of low back pain include intervertebral disc pathologies such as annular tears, disc herniations, degenerative disc diseases, facet joint osteoarthritis, degenerative spondylolisthesis and spinal stenosis. Rare causes of back pain include connective tissue disease and inflammatory spondyloarthropathy such as ankylosing spondylitis, infections such as spondylodiscitis, tumours and pathological fractures.

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

The family physician’s key role in the management of acute low back pain includes identifying and diagnosing serious aetiologies of back pain, relieving the patients’ pain through various methods including physiotherapy and analgesia, and providing the patient with ample, legitimate rest with medical certificates or excuse letters.

History taking

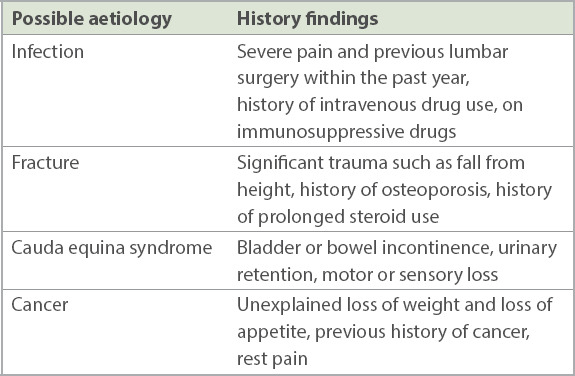

A comprehensive and thorough history is the first step to reaching a correct diagnosis for the patient’s complaints. General information related to the pain can first be elicited through questions, including the exact location of the pain on the back, onset, character, duration and time course, associations, exacerbating and relieving factors, and severity. It is important to then exclude any red flags of back pain from serious aetiologies, by asking for a history of cancer, unexplained weight loss, immunosuppression, intravenous drug use, symptoms of urinary tract infection, fever, history of significant trauma, urinary retention, and bladder and bowel incontinence.(1,5) The presence of these red flags warrants a further workup to rule out serious aetiologies of acute low back pain such as major intra-abdominal pathology, cauda equina syndrome, fractures and malignancy (Table I).(6)

Table I.

Red flags for serious aetiologies in history taking.

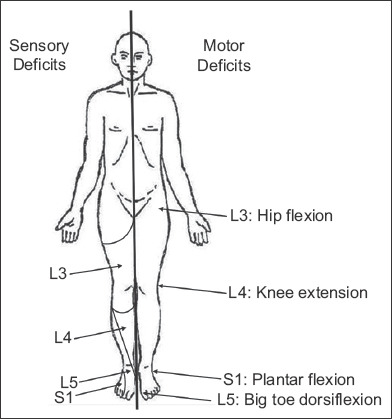

Further history can then be obtained regarding the presence or absence of sciatica. The presence of radiation of pain often provides a clue to the aetiology of the back pain. Bilateral lower limb pain may point towards a central disc prolapse or a diagnosis of spinal stenosis. Unilateral lower limb pain in a dermatomal distribution implies compression, impingement or irritation of the nerve root. Pathologies at the L1–L3 nerve roots correspond to pain at the hips and thighs, while pathologies at the L4–S1 nerve root correspond to pain below the knees to the foot and ankle. More detailed localisation of motor and sensory loss may be attempted by consulting the American Spinal Injury Association chart, which maps specific muscular actions and dermatomes to the respective neurological levels.

The patient’s occupation, whether sedentary and deskbound or an active job that requires physical exertion, is also an important component of the history. Information such as recent heavy lifting or change in exercise regimen, prolonged sitting or poor ergonomics, or even a bad chair can provide a clue to the cause of the back pain. It is also important to check if the patient has any functional deficits resulting from the low back pain. With all the information at hand, the physician will then be able to formulate a treatment plan with regard to activity modification and improving workplace ergonomics for the patient, so as to relieve the low back pain and prevent recurrence.

Physical examination

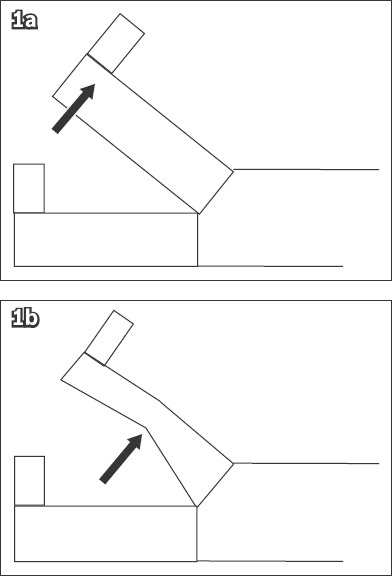

A standard ‘look, feel, move and special tests’ system of evaluating the musculoskeletal system should be performed. Special tests include the straight leg raise test (Fig. 1). This is useful for identifying lumbosacral nerve root tension, usually due to lumbar discopathy and nerve root irritation. It is also important to conduct a thorough neurological examination, as the level of pathology in the spine can then be localised (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Illustrations of the straight leg raise test show (a) the patient’s leg raised (arrow), when the physician can observe for pain radiating down the leg to the buttock of the patient; and (b) the ‘bowstring’ sign (arrow), whereby bending the knee slightly relieves the pain, followed by a further reproduction of the pain upon applying pressure to the popliteal fossa to stretch the sciatic nerve again.

Fig. 2.

Simplified pictorial diagram shows the neurological findings in low back pain and correlation to the affected nerve root.

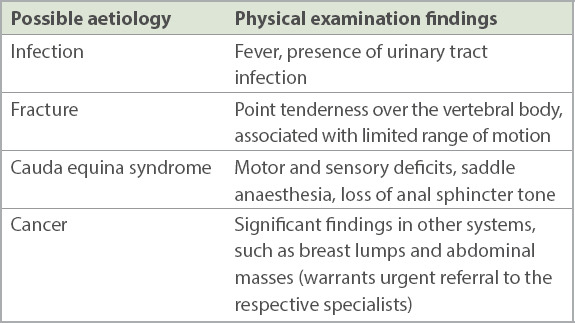

Key red flags should be excluded (Table II). These include the presence of new neurological deficits such as saddle anaesthesia, loss of anal sphincter tone, major motor weakness in the lower limbs, the presence of fever and progressively worsening neurological findings persisting beyond a month.(1)

Table II.

Red flags for serious aetiologies in physical examination.

In summary, notwithstanding the importance of red flags, in order to accurately diagnose and treat a patient with acute low back pain, the family physician needs to take a comprehensive history and perform a thorough physical examination, and not solely rely on a checklist of red flags.

Investigations

Imaging is generally not indicated for most patients with low back pain. However, in patients whose pain persists beyond six weeks or who have signs and symptoms indicating a serious underlying aetiology, it is necessary to perform diagnostic imaging.(7-10)

Plain radiography (i.e. X-ray) may be a useful screening tool for obvious pathologies but tends to have little diagnostic value, it has have low sensitivity and specificity.(11) If the radiographs are unremarkable but clinical suspicion is high for a serious pathology, it is appropriate to refer the patient to a specialist for further investigations with magnetic resonance (MR) imaging.(1) MR imaging allows for a detailed, three-dimensional view of the soft tissues and bones as compared to radiography. Computed tomography (CT) of the spine is indicated if there are contraindications to MR imaging. It is important to correlate the findings of CT and MR imaging with clinical findings, as false-positive results increase with age.(12) Blood tests such as full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level may be performed if infections or bone marrow neoplasms are suspected.

Treatment

Education and activity modification

After ruling out serious aetiologies, treatment plans with the goals of pain relief, functional improvement and minimisation of time off work can be formulated with the patient.(13) For patients with non-specific acute low back pain, evidence shows that individualised patient education is more effective than no education in relieving a patient’s pain.(14) The discussion with the patient should involve explaining the benign nature of the pain, with reassurance that improvement will happen with time. The patient should be educated on the importance of adopting a good posture when sitting or standing, as well as proper lifting techniques, such as bending at the knees when lifting heavy objects and avoiding excessively twisting and bending when doing so. Workplace and/or work-from-home ergonomics should be discussed with patients, so that they can implement changes that will help to improve posture and reduce back pain. The patient should also be advised against bed rest. It is less effective than staying active in terms of relieving pain and improving function.(15) Prolonged bed rest will lead to muscle wasting, joint stiffness and an overall decrease in function for patients. It can even lead to serious consequences such as pressure ulcers and venous thromboembolism.

Physical therapy

Patients should be encouraged to start physiotherapy early for the treatment of low back pain. Physiotherapist-directed home exercises are effective in relieving pain, reducing recurrence and improving overall function. These exercises are generally divided into movement exercises and strengthening exercises. Movement and stretching exercises, including the McKenzie method, help to restore movement and minimise stiffness, which in turn relieves back pain. Strengthening exercises help to improve core muscle stability, preventing further strain on the back and improving overall back stability. These exercise programmes are a cost-effective treatment for low back pain, increasing time intervals between episodes of back pain and reducing time off work.(16,17)

Simple stretches include the knee-to-chest stretch and lower back rotational stretch. In the knee-to-chest stretch, the patient is advised to lie supine on the floor and pull one knee towards the chest and hold it against the chest for five seconds before repeating with the other knee. In the lower back rotational stretch, the patient is advised to lie supine on the floor, keeping the shoulders firmly on the floor. Next, the patient needs to roll both bent knees to one side, holding the position for 5–10 seconds, before rolling both knees to the other side. Another simple method for relieving back pain is getting the patient to lie supine on the floor and placing a tennis ball between the back and the floor, particularly on the areas of the back where the muscles are tight. Simple side-to-side rolling actions can be performed, releasing the tight muscles and relieving the pain (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Illustration shows a tennis ball under the back.

Application of ice on the acute onset of low back pain may also provide short-term relief of pain and improvement of disability.(18) However, it may not be useful beyond early low back pain.

Other methods for pain relief include acupuncture,(19) the use of lumbar support,(20) massage(21) and chiropractic spinal manipulation.(22) These modes may produce short-term pain relief but are generally not supported by strong, high-quality evidence.

Pharmacological therapy

Acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are usually the first-line therapy. They are effective in providing short-term relief. Notably, NSAIDs are no more effective than acetaminophen, and there is no NSAID that is superior. However, for some patients, if the first NSAID is ineffective, switching to a different one may also be considered.(23) Prior to starting on NSAIDs, it is important to review the patient’s profile, with consideration of risk factors such as the presence of renal impairment and cardiovascular diseases. NSAIDs should be used at the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible period of time(24) and should not be taken continuously. The patient should be reviewed in 1–2 weeks if the pain has not significantly improved.

Taking guidance from the World Health Organization analgesic ladder, opioids, another commonly prescribed drug for pain relief in low back pain, can then be considered in persistent pain despite NSAIDs. However, it is to be noted that some studies have shown no difference in pain relief and time off work between NSAIDs and opioids.(25) In addition, opioids have a risk of harmful dose escalation over time. Opioids also have significant adverse effects such as drowsiness, nausea and dizziness, requiring the physician’s discretion for cautious use.

WHEN SHOULD I REFER TO A SPECIALIST?

Patients who present with features suggestive of cauda equina syndrome or underlying serious spinal pathologies should be referred to a spine surgeon expeditiously for further workup. Patients with pain that lasts for more than six weeks, causing significant functional impairment, should also be referred to a spine surgeon.

In summary, it is important to exercise clinical judgement in using the various treatment methods in isolation or in combination depending on patients’ ideas, expectations and concerns. It is also important to review patients at appropriate intervals and consider referrals to a specialist or even urgent referrals to the emergency department if acute changes such as sudden neurological deficits occur.

USEFUL LINKS

Ways to turn good posture into less back pain: https://www.health.harvard.edu/pain/4-ways-to-turn-good-posture-into-less-back-pain (accessed 4 June 2021)

Proper lifting techniques: https://ergo-plus.com/wp-content/uploads/WA-Handout-Proper-Lifting-Techniques.pdf (accessed 4 June 2021)

Workplace ergonomics: https://relaxtheback.com/blogs/news/workplace-ergonomics-how-to-improve-your-posture-at-work (accessed 4 June 2021)

The McKenzie Method: https://www.mckenzieinstitute.org/clinicians/mckenzie-method (accessed 4 June 2021)

Lower back stretches: https://www.healthline.com/health/lower-back-stretches (accessed 4 June 2021)

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

Accurate and comprehensive history taking and physical examination are needed to rule out serious causes of acute lower back pain, including cancers, fractures, infections and cauda equina syndrome.

Imaging is indicated in patients with acute lower back pain when red flags are present. It is also prudent to offer imaging to patients whose symptoms persist after six weeks of treatment.

Treatment goals can include pain relief, function improvement and minimisation of time off work.

Physiotherapy and exercise programmes are cost-effective treatments for reducing pain, recurrence and disability in patients with acute lower back pain.

Bed rest should not be recommended for patients with non-specific acute lower back pain, as it leads to various adverse effects including muscle deconditioning and joint stiffness.

Medications such as NSAIDs, acetaminophen and muscle relaxants are effective first-line treatments for pain relief in patients with acute lower back pain.

NSAIDs should be used at the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible period of time, with consideration and monitoring of risk factors such as presence of renal impairment and cardiovascular diseases.

Jonathan visited your clinic one month later for a follow-up. He happily reported that his back pain had improved. He had completed your prescribed one-week course of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and did not require a further course of analgesia. He was actively practising the stretching exercises that you taught him. He had also heeded your advice and reduced the intensity of his calisthenic workouts and modified his work-from-home routine, incorporating adequate breaks while working as well as improving the ergonomics of his home office.

REFERENCES

- 1.North American Spine Society. Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine Care:Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain. [Accessed August 28, 2020]. Available at: https://www.spine.org/Portals/0/assets/downloads/ResearchClinicalCare/Guidelines/LowBackPain.pdf .

- 2.Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health, Singapore. National Health Survey. 2010. [Accessed September 22, 2020]. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/reports/national-health-survey-2010 .

- 3.Fatimah MK, Chng SL, Gan SL, Lim SL Workplace Safety and Health Institute. Overview of back pain cases in Singapore from 2013-2015. [Accessed September 22, 2020]. Available at: https://www.wshi.gov.sg/-/media/wshi/posters/posterfile/overview-of-back-pain-cases-in-singapore-from-2013-2015.pdf .

- 4.Hartvigsen J, Hancock M, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. The Lancet. 2018;391:2356–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Downie A, Williams CM, Henschke N, et al. Red flags to screen for malignancy and fracture in patients with low back pain:systematic review. BMJ. 2013;347:f7095. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casazza BA. Diagnosis and treatment of acute low back pain. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:343–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerry S, Hilton S, Dundas D, Rink E, Oakeshott P. Radiography for low back pain:a randomised controlled trial and observational study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:469–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care:an updated overview. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:2791–803. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5673-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians;American College of Physicians;American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain:a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, Deyo RA. Imaging strategies for low-back pain:systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:463–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel ND, Broderick DF, Burns J, et al. ACR Appropriateness criteria low back pain. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13:1069–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung KM, Karppinen J, Chan D, et al. Prevalence and pattern of lumbar magnetic resonance imaging changes in a population study of one thousand forty-three individuals. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:934–40. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a01b3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker A, Heiko H, Redaelli M, et al. Low back pain in primary care:costs of care and prediction of future health care utilization. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:1714–20. doi: 10.1097/brs.0b013e3181cd656f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engers A, Jellema P, Wensing M, et al. Individual patient education for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2008:CD004057. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004057.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagen KB, Hilde G, Jamtvedt G, Winnem M. Bed rest for acute low-back pain and sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD001254. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001254.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gellhorn AC, Chan L, Martin B, Friedly J. Management patterns in acute low back pain:the role of physical therapy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:775–82. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d79a09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RW, Forciea MA Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain:a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514–30. doi: 10.7326/M16-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French SD, Cameron M, Walker BF, Reggars JW, Esterman AJ. A Cochrane review of superficial heat or cold for low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:998–1006. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000214881.10814.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin DC, et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD001351. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001351.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Duijvenbode I, Jellema P, van Poppel M, van Tulder MW. Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2008:CD001823. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001823.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furlan AD, Giraldo M, Baskwill A, Irvin E, Imamura M. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD001929. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001929.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker BF, French SD, Grant W, Green S. A Cochrane review of combined chiropractic interventions for low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:230–42. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318202ac73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enthoven WTM, Roelofs PD, Koes BW. NSAIDs for chronic low back pain. JAMA. 2017;317:2327–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s:assessment and management. NICE guideline (NG59) 2016 Nov 30 [online] [Accessed August 27, 2020]. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59 . [PubMed]

- 25.White AP, Arnold PM, Norvell DC, Ecker E, Fehlings MG. Pharmacologic management of chronic low back pain:synthesis of the evidence. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36(21 Suppl):S131–S143. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822f178f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.